Abstract

Mentors support novice teachers in the critical stages of their learning, which has an effect on novice teachers’ ability to engage in teaching and to stay in the teaching profession for years. The mentor teacher also helps the novice teacher become well integrated and develop professionally. The current study aims to examine the factors that motivate mentor teachers to occupy this position, the guidance and support components of the role and their implementation in the mentoring process, and the frequency and planning of the encounters between mentor and novice teachers, in the context of the Israeli education system. Also examined are the attitudes of mentor teachers towards their role and their perceived ability to operate efficiently. The research population comprises 46 research participants who mentor novice teachers in high schools in Israel. Analysis of their attitudes shows that the factors that motivated them to serve as mentor teachers are related to a consciousness guided by a sense of personal mission and intrinsic motivation to promote novice teachers. Also, factors related to realizing their personal values and aims, such as realizing a vision, personal satisfaction, interest, and challenge, were found to be common. According to self-reported findings, mentor teachers were very helpful to novice teachers on issues such as class management, managing and planning teaching, evaluating students, and nurturing a professional identity. They also supported emotional aspects related to the teaching process, including their sense of efficacy and contact with the students. Mentor teachers felt a great deal of satisfaction with the mentoring process and would recommend this experience to other teachers to a high degree. Hence, a teacher who chooses the profession from a sense of a personal mission in the education system will also see their mentoring role as a mission for the sake of the next generation. Leaders in the education system are advised to develop a more holistic mentoring model that incorporates the traditional mentoring model yet guides us towards a mentoring process that is better adapted to the postmodern era, and is based on a long-term strategy for helping retain novice teachers within the education system.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Mentoring Process

Supporting novice professionals through mentoring has gradually become gradually customary in the first two decades of the 21st century in the fields of health, politics, business, and education. The understanding that induction into a new profession involves not only learning formal knowledge but also matching theoretical knowledge to the unique needs of the new worker has led to a recognition of the importance of mentorship as a framework that entails regular and continuous support to facilitate the self-realization of workers in their professional development within the organization.

Mentorship and support during teachers’ induction is composed of processes intended to allow novice teachers (teachers in their first year of practice) to contend with the “shock of reality” in the education system and remain in the profession [1,2]. Mentorship is a process intended to provide professional support for the development and enhancement of teaching skills in novice teachers’ critical first year of practice [3]. The mentor teacher represents professional expertise that defines the boundaries of the profession for the novice teacher in a framework that combines knowledge, facilitation, evaluation, and supervision [3]. According to Matthews, 2015, mentorship consists mainly of emotional support and alleviating the tensions created by the conflict between professional demands and personal needs [4]. It is assumed that the mentorship process can help enhance novice teachers’ confidence and self-esteem and sustain them emotionally and professionally [5].

Novice teachers who transition from the status of student to that of teacher must be proficient practice-oriented individuals. Nevertheless, they lack practical knowledge of teaching techniques and skills, sources and resources, and existing curricula. They also lack contextual knowledge regarding the specific educational institution in which they are placed. All of this is supposed to emerge during the process of mentorship and support [6].

Receiving support in the form of a professional discourse between new professionals and experienced colleagues in the first year of work predicts less burnout and turnover among novice teachers [7]. In recent years, a collaborative approach has emerged, such that mentorship nurtures the learning and professional development of both the mentor teacher and the novice teacher in an effective process based on partnership, openness, and reciprocity [8]. The mentor teacher too experiences personal and professional learning and development [9]. This approach sees mentorship as another level in teachers’ professional development [10], and accordingly, it combines the need to construct a process of professionalization and more thorough engagement by focusing on unique knowledge and practices.

1.2. The Role of Mentor Teachers

The mentor is required to conduct regular weekly meetings of one hour with their mentee at a fixed time to discuss issues that arise in the course of the mentee’s work. The mentor must observe at least two lessons by the novice teacher in each semester, after scheduling the observation in advance with the notice teacher. Each observation must be documented and followed by a feedback conference. The mentor also plays an active role in assessing the novice teacher’s suitability for the profession by providing an evaluation of the novice teacher’s performance at two stages: a formative mid-year evaluation and a summative evaluation at the end of the year, in preparation for the issue of their teaching license.

The mentor’s role in the organizational socialization process is essential for novice teachers [11], as its aim is to provide a consistent and systematic experience for the novice teacher in their new profession and organizational context [12]. The mentor trains the new teacher during their first year and provides personal and professional guidance as well as emotional support such as enhancing the novice teacher’s self-image by establishing a relationship of trust with the mentee. Professional guidance includes the development of the mentee’s professional identity, guidance in teaching skills, class management, and the development of a professional state of mind. In addition, they help novice teachers integrate into the educational institution by providing information about the school environment, rules and regulations, and rights and obligations [13]. The mentor cultivates the mentee’s essential work skills through various means, including joint planning, observations, feedback, and joint analysis of students [14].

Bradbury noted that the mentor has five roles: befriending, offering suggestions, advising, training, and assisting [15]. Other researchers recommend educational mentoring in two dimensions [16]: emotional support that enables a comfortable relationship and environment for the novice teacher’s personal development, and professional support based on the principles of understanding teachers and their way of working [17]. Novice teachers need practical knowledge and logistical information, the exchange of practical knowledge with experienced teachers, reflective discussions with colleagues, and emotional support without pressure.

1.3. Who Is the Mentor Teacher?

A mentor teacher is an experienced educational practitioner who provides pedagogical, social, and organizational support to a novice teacher who is in their first year of practice. In the Israeli education system, each novice teacher is assigned a mentor for one year, in their first year of teaching, as part of the efforts of the education system to strengthen the professional status of teachers. Mentoring allows novice teachers to optimally integrate into the education system, making the best use of their abilities, and promoting novice teachers’ current and future contributions [13].

A mentor must be an accredited teacher, holding either a teaching certificate or a teaching license, and have at least four years of experience in teaching. In general, the mentor will be a member of staff in the school where the novice teacher is employed. Mentors must have a positive attitude toward onboarding new teachers based on a desire to empower their colleagues’ success in teaching. Mentors are also required to complete a 60 h training course given at a teacher-training institution. Remuneration is equal to a 2.4% monthly bonus for each mentee.

The mentor teacher is a professionally inspiring educator who has gained the admiration of the school’s teaching staff. The mentor has a high status among the teaching staff and management and is expected to help the intern become integrated into the school and form connections with teachers and staff. The mentor has knowledge and experience of teaching as well as the desire to share their knowledge with novice teachers. Mentors are able to explain and demonstrate good teaching, and can identify and discuss dilemmas and problems that arise in the course of the teaching practice. The mentor provides professional, emotional, and organizational support and serves as the pedagogical authority that promotes the novice teacher’s professional practice. The mentor has professional knowledge in various fields and helps the novice teacher expand their knowledge of the relevant subject areas and how to identify students’ needs. The mentor provides answers to the issues and challenges that the novice teacher encounters, such as class management or communications with parents. The mentor has the ability and the willingness to provide emotional support to the novice teacher and to help the novice teacher cope with frustration and other challenges by providing encouragement and positive reinforcement [18].

1.4. The Importance of Mentoring Novice Teachers

In Israel, in their first year in the profession, novice teachers are assigned a mentor who works with them during school hours, and also participate in an internship program, both of which are intended to help novice teachers cope with the difficulties and frustration at the stage of induction into teaching and persevere in the profession [19].

There is broad consensus regarding the importance of the mentorship process for the professional development of teachers [13,20]. In the mentorship relationship, mentees receive practical support that helps them acquire self-confidence, solve problems, and implement critical thinking competencies, and thus influence learners [21,22]. The concept of mentorship encompasses interpersonal dialogue between mentor and mentee based on the relationship formed between them. The classical conception of mentorship sees the mentee as a protégé and the mentor as a person with experience, maturity, and proven fields of expertise who harnesses these resources to provide the mentee, who is younger or less experienced, with an opportunity for development and growth. Mentorship focuses not only on ‘what needs improving’ but also on ‘how to do it in real-time’. A relationship of trust is vital for the success of this support, and to build trust and strengthen it, various tools are utilized during the process, such as joint planning, exchanging opinions, mutual observation, giving advice, and learning from experience. Fundamentally, the mentorship process emphasizes the development of the mentee’s abilities and realizing their designation. Most mentorship models that focus on processes of personal growth or professional development are appropriate when the mentor and mentee come from the same sector, similar fields of occupation, and, at times, the same organizational environment [23]. Kearney and Klinge found that a strong relationship between the mentor teacher and the novice teacher is a major condition for the success of the mentorship [24,25]. The mentorship of a novice teacher by an experienced teacher has also been found to be based on shared fields of interest. This approach assumes that the mentee strives to emulate the mentor to some degree or in some aspects [15,26].

The research literature may be divided into three categories: empirical research and case studies, intervention programs and personal descriptions, and literature reviews and policy papers [27]. These researchers have also identified different types of support that novice teachers receive—mentors, in-service training, and collaborative work with experienced teachers—that are have a positive impact on novice teachers, their teaching practices, and their attitudes toward teaching. Each type of support additionally affects other outcome measures including increased retention, adjustment to the school’s organizational culture, and the ability to teach according to the curriculum. In-service training for novice teachers was specifically found to improve classroom practices and students’ achievements. Specifically, support for novice teachers in their first year of practice was found to be more effective in preventing attrition compared to support given in subsequent years [7].

1.5. Challenges and Difficulties Faced by Novice Teachers

At the stage of their induction into teaching, novice teachers experience a dramatic transition from the teacher-training college to their new school [28]. The initial difficulty evident upon their induction into the teaching profession is the sense of shock experienced by novice teachers. Novice teachers begin their professional journey from a position of idealism and belief in their willingness and ability to work hard. For many, the difficult conditions of teaching in the classroom are quickly revealed. Particularly in their early years of teaching, novice teachers are required to cope with complex demands in challenging classrooms, frequently without a supportive organizational climate.

The challenges that teachers face when beginning work have been described as a “war of survival” and encountering a “practical professional shock” [29]. The encounter with reality in the field is described in the literature via metaphors such as “culture shock” [30] and “baptism by fire” [31]. Novice teachers transitioning from the training stage to the stage of professional practice meet with difficulties that generate strong feelings of helplessness, loneliness, alienation, foreignness, and insecurity and afflict them to the degree of paralysis. Sometimes, teachers must conceal their pain and repress their feelings and deliberations to comply with the organization’s demands and integrate within systemic norms. The workload and the need to deal with a large number of lessons hasten novice teachers’ decisions and also add to an experience of emotional burden [32] and burnout. At this stage, many teachers tend to “float or drown” [16], and a considerable proportion of novice teachers choose to leave the profession [33]. In Israel, this proportion reaches 16% on average, and might eventually lead to them dropping out of the system entirely, primarily in the first two years [34].

The novice teacher experiences three types of difficulties:

- Emotional and psychological stress—These difficulties can stem from several factors: the frequently changing character of the education system; the very complex nature of teaching work; coping with different elements within the system, such as principals, inspectors, teachers, parents; and the need to bridge and balance the demands of the profession and familial–personal needs. These difficulties can manifest as considerable fatigue, restlessness, frustration, and a sense of despair.

- Difficulties with teaching—These are practical and technical difficulties that derive from a dearth of skills and techniques related to different aspects of the teaching practice and a lack of routines and habits. These difficulties include discipline problems, problems involving class management, problems relating to diversity, the evaluation of assignments and exams, and contact with parents, class management, issues with study materials, knowledge of specific disciplines, and students’ personal problems [35]. Novice teachers experience some of these issues during their training but often without overall responsibility, so they must learn about them while working in teaching and education.

- Difficulties with developing a professional identity—The novice teacher joins the field of teaching and education with personal perceptions regarding good teaching, proper learning, and efficient educational approaches. These perceptions are formed from the teacher’s experience as a student at school, their academic studies, and their teacher-training studies. In their first encounter with teaching, it becomes evident that these perceptions are not always applicable to the circumstances in the educational workplace.

1.6. Organization Culture and Climate Contribute to the Retention of Novice Teachers

Novice teachers’ adjustment to the school climate and environment is extremely important [36] and significantly affects their satisfaction and burnout. A study found that, the less the climate was perceived as being supportive, the greater the sense of tension and burnout, and vice versa, the more the climate is considered to be supportive, the more such emotions are alleviated [33].

Fresko and Alhija claim that the processes within the socialization of novice teachers with the school staff are a major cause of their satisfaction in the first year of work [37]. Their findings show that schools mostly provide interns with support from a mentor, help from the principal, and the assistance of colleagues. Nevertheless, some novice teachers reported a lack of support from their teacher colleagues [38].

The institutional credo, the procedures utilized within the system, the customary work and communication methods among the team—all these and others create the unique institutional culture of each institution. The intake of new teachers requires the educational environment to create proper, functioning, conditions, an environment that allows professional and personal establishment and development.

The teachers’ lounge is a unique informal environment that teachers use during their breaks, to work, and meet with other teachers. All schools in Israel have a teaching lounge. Meetings with the school administration, the professional staff, the didactic staff, and the psychological staff are held in the lounge, which is equipped with a broad range of pedagogical aids that teachers can use. Teachers hold conversations, share their experiences with different methods of teaching and ways of coping with the pressures of the profession, learn about students and school norms, and provide each other with mutual support. In the Israeli context, the teachers’ lounge contributes significantly to the body of knowledge about teacher communities and their professional lives [39], which is especially important for novice teachers, who may find it hard to understand the organizational culture at their school and might find themselves lacking the necessary tools to contend with problems and difficulties [40].

Mentoring is another more formal resource for novice teachers. The traditional mentoring model used in schools is based on a hierarchic outlook whereby the mentor is the teacher with experience and professional knowledge, while the novice teacher lacks experience, is guided by the mentor, and operates accordingly [41]. The traditional model (see Figure 1) applied in Israeli high schools today is based on weekly mentor–mentee meetings.

Figure 1.

Traditional mentoring model in the education system.

1.7. Motivators and Characteristics of the Mentorship Process

While mentors are selected by the school principal, the position is typically awarded to teachers who embrace the opportunity to mentor novice teachers. Mentors are generally selected for the role on the basis of their personal traits, including their willingness to invest the time and effort to serve as role models, and apply their experience and expertise to guide novice teachers. A mentor’s personality is thus the main consideration in the selection process, but a suitable personality is neither a necessary nor a sufficient criterion for selection. Mentors and school principals report that a teacher’s expertise in a specific specialty is an important reason for their selection. The selection of mentors is apparently based on a combination of personal traits, didactic skills, and disciplinary knowledge [42].

Mentors are motivated to do assume the role of a mentor for diverse reasons. Empirical research finds two main categories of motivation: (a) Self-focused motives, such as an opportunity to learn, to gain admiration, to influence others. A mentor motivated by such motives conceptualizes mentorship as a reciprocal relationship with a mentee in which the mentee’s developments is an important and intentional part of the process rather than a by-product; and (b) other-focused motives, such as the opportunity to help, build other people’s competencies, respect and pass on traditions, and realize personal and professional beliefs. Here, mentorship is conceptualized as the realization of the mentor’s need to foster and train young professionals and contribute to future generations [43]. Mentors report that they choose to become mentors in order to contribute to the professional development of novice teachers, share their knowledge, and contribute to their own professional development.

The theoretical distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation contributes to our understanding of different behavior motives and is also a customary tool for understanding the motivations which underlie occupational choices, the choice of a professional training track, and the image and attractiveness of professions. Two types of causes explain mentor teachers’ decision to occupy this role: intrinsic motivators and extrinsic motivators [43]. Intrinsic motivators lead to actions that stem from interest and pleasure, while extrinsic motivators lead to actions that stem from anticipated benefits; for teachers, such motivations include the satisfaction of promoting students’ learning, “collegial stimulation” provided by teacher colleagues, and intellectual involvement [44]. Motivations for occupying the role of mentor are based on factors that are known to encourage teachers to choose a career in teaching: assisting students, imparting knowledge, and the desire to develop personally and professionally. Moreover, extrinsic motivations, which have a low weight in teachers’ career choice to begin with, will probably have little weight in the choice of becoming a mentor teacher [45].

These motivations are defined as elements perceived by the individual as generating benefits originating from the goals of teaching and its fundamental characteristics and are perceived by future teachers as being compatible with their skills and personality [45]. Among the most significant motivators for choosing teaching, which has a low status and is accompanied by few material rewards, is the need for self-realization, which heads Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs” theory [46]. Individuals tend to choose a profession in which they think they will be able to realize themselves in the most significant manner and in which they expect to express their unique skills. For example, working with children and youth, a fundamental characteristic of teaching, is an intrinsic motivator typical of many who choose to engage in teaching. Some see themselves as people with social awareness and seek to engage in a field that involves interpersonal contact. Engaging in the teaching discipline is a fundamental characteristic as well [47].

There is an association between the function of mentor teachers as models of effective teaching and as coaches who support the development of novice teachers and the latter’s sense of preparedness for teaching at the end of their training period [46]. A mentor is someone who shares their knowledge, skills, and/or experience to help another to develop and grow and constitute role models for effective teaching, while a coach is someone who provides guidance to a client on their goals and helps them reach their full potential. The more positively novice teachers perceive the coaching practices of their mentor teachers, the more ready they feel to teach [48]. The support they mention is manifested in providing assistance with teaching in their discipline, frequent and appropriate feedback, a balance between autonomy and support, cooperative work, shared planning, joint teaching, help with job seeking, maintaining satisfaction, and remaining in the profession [49]. The strongest predictors of novice teachers’ sense of satisfaction at the end of their first year were found to be the support of the mentor teacher, the principal, and their colleagues; the workload; and completing teacher-training studies before beginning work [37]. Orland-Barak claimed that mentorship has a positive effect on novice teachers remaining in the profession [50].

2. Purposes of the Study

The goals of the study were to examine the perceptions of mentors about novice teachers in Israeli high schools, and specifically their personal motivation for choosing the mentoring role, their perceptions of the role, their perceived personal ability to effectively mentor novice teachers, the material reality of mentoring, and the nature of their encounters with their mentees.

3. Research Procedure

The research participants consisted of 46 teachers who serve as mentors to novice teachers in Israeli high schools. Using the convenience sampling method, we asked novice teachers who participated in a workshop in an academic institution to name their mentor in an online questionnaire. We then contacted the mentors. Mentors who agreed to participate in an online survey were informed that their information would be anonymized and would be used only for research purposes. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the research population: gender, age, and length of teaching experience.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study participants.

3.1. Research Tools

The research data were collected via a structured self-report questionnaire developed as part of the Proteach (Promoting Teachers’ Success in Their Induction Period) program, which is an experimental program for integrating an incubator model for novice teachers into the Israeli education system. The program was supported by the EU Erasmus+ program and was led in Israel by Kibbutzim Seminar and Mofet Institute, in conjunction with six teacher training colleges in Israel and four European institutions.

The current study used the assessment tool developed for mentors in the Proteach project. This self-report questionnaire was built based on existing and valid research tools. With the exception of the background questions, respondents rated their agreement to items on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The reliability of the questionnaire was very high (α = 0.98) [34].

3.2. Research Questions

- 1.

- What are the factors that motivate teachers in the Israeli education system to choose the role of mentoring novice teachers?

- 2.

- What elements of mentoring are provided to novice teachers?

- 3.

- What are the perceptions of mentor teachers in the Israeli education system regarding their role as mentors in the education system?

- 4.

- What is the nature of the encounters between the mentor teacher and the novice teacher (frequency of encounters, extent of planning the encounters, and factors that affect the planning of the encounters)?

- 5.

- To what extent are mentor teachers able to work effectively with their mentees?

4. Research Findings

The first research question addresses the intrinsic and extrinsic motivators that caused experienced teachers to mentor novice teachers in the education system. Table 2 presents the attitudes of mentor teachers to choosing this role.

Table 2.

Factors underlying the choice to occupy the role of mentor teacher in school.

The data presented show that the motivations of mentor teachers to engage in their role are mainly intrinsic. These are associated with the basic features of teaching, thinking, a personal mission, and contributing to the education system by promoting novice teachers, and include, on the highest level, reports of factors associated with realizing their values and personal goals, such as realizing a vision, personal gratification, interest, and challenge. Factors associated with personal or professional development were reported to a moderate degree. Extrinsic factors, such as the financial factor or the request of the principal that they take part in the process, were mentioned only to a limited degree.

The second research question focuses on the extent to which guidance and support content were provided to novice teachers by mentor teachers in their first year at the school. Table 3 shows the extent to which mentors provided various elements of guidance and support to novice teachers.

Table 3.

The extent to which guidance and support content were provided to novice teachers.

The mentor teachers noted that they made significant contributions to novice teachers in the areas of teaching, class management, and disciplinary knowledge (coping with difficulties in teaching, sense of efficacy, and others). Their contributions to the mentees’ pedagogical knowledge (assistance with innovative teaching methods, familiarization with the study program, managing and planning teaching, and others) were also perceived as considerable, although slightly less so. Their contributions to increasing novice teachers’ sense of belonging to the organization, integration into the school staff, relations with the management, cooperation with the parents, familiarization with the organizational culture, and others were also perceived as considerable but less than the two previous dimensions.

The third research question focuses on the attitudes of mentor teachers to their role as mentors of novice teachers within the education system. Table 4 presents the attitudes of mentor teachers regarding their role in supporting novice teachers.

Table 4.

The attitudes of mentor teachers to their mentorship role.

The attitudes of the mentor teachers regarding their role showed that, in their opinion, mentoring does not constitute an obstacle to performing their other roles in the education system optimally. They believe that they have the necessary foundation and tools to be effective mentors and provide a good response to novice teachers’ needs, although they also noted that they did not receive suitable training for mentoring novice teachers. Coordinating expectations with the novice teacher is perceived as an important part of their role, their areas of responsibility as mentors are clear to them, their work is satisfying, they feel that the school supports their work, and they would recommend the role of mentor to other teachers. Moreover, the mentors clearly perceived their role as moderately contributing to their own professional development: developing instruction skills, improving their reflective ability, and thus improving their teaching, and learning from the novice teacher. Most of the mentor teachers claimed that their status in the school did not change as a result of this role.

The fourth research question focuses on the nature of encounters between the mentor teacher and the novice teacher in terms of their frequency (Table 5) and the extent to which they were planned (Table 6).

Table 5.

Frequency of encounters between the mentor teacher and the novice teacher.

Table 6.

Planning the encounters with the novice teacher.

The data show that encounters between the mentor teacher and the novice teacher at the school are held at a high frequency. As shown in Table 5, 71.2% of mentors meet with the novice teacher at least once a week.

Most encounters between the mentor teacher and the novice teacher are planned and scheduled in advance. Consequently, the study examined the extent to which planning is affected by various factors (Table 7).

Table 7.

The effect of different factors on planning the encounters with the novice teacher.

Most of the novice teachers’ encounters with the mentor teacher are planned according to the requests of the novice teacher. The next highest priority is given to requests related to school needs, with the Ministry of Education directives given the least priority. In sum, most respondents (71.4%) reported that no set hour had been defined in the curriculum for talking with the novice teacher, and the frequency of their encounters is also usually not fixed. Accordingly, the mentor teachers reported that the encounters with the novice teacher are planned only to a moderate degree.

The fifth research question focuses on the mentor teacher’s capacity to operate effectively when training novice teachers at the school. Table 8 presents the mentors’ perceived capacity to work effectively with the novice teacher.

Table 8.

The capacity of the mentor teacher to operate efficiently with the novice teacher.

The mentor teachers believe that they are effective in providing emotional support and advancing the novice teacher in different aspects of their teaching practice, including improving classroom skills by observing classes and providing evaluation. Mentor teachers feel that they make a moderate contribution to novice teachers’ independence and autonomy, and a limited contribution to their mentees’ integration into the institutional culture and providing explanations about working terms at the school.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Mentorship is a milestone in the socialization of novice teachers. It is a practice based on peer learning, interpersonal relations, and mutual relations between an experienced professional and a new professional in the first stages of their career [50]. The availability of a mentor is an important and significant source of support for the recruitment of novice teachers in many countries. The contribution of mentoring is described as providing a professional, social, and emotional anchor for novice teachers upon their entry into the profession [38].

The first research question related to motivations that lead teachers to choose the role of mentor for novice teachers. Teachers’ choice of the role of mentor was found to derive, to a large degree, from intrinsic motivations: the desire to contribute to the system, to promote and develop school processes, to promote and nurture a new generation of teachers, interest and challenge, personal satisfaction, realizing their vision as educators, improving their teaching skills, exposure to new pedagogies and receiving updates about them, and others. To a lesser degree, their choice derived from extrinsic motivations such as pay.

The second research question related to the guidance and support components of mentorship and to what degree they are implemented in the process of mentorship within teachers’ in-service training. Mentor teachers stated that they contribute to novice teachers to a great degree in the context of teaching, class management, and disciplinary knowledge. Their contributions to imparting pedagogical knowledge, familiarization with the study program, and managing the teaching and its planning were also perceived as considerable, although slightly less so. They make major contributions to increasing novice teachers’ sense of belonging to the organization, integration with the school staff, cooperation with the parents, familiarization with the organizational culture, and others.

The third research question related to mentor teachers’ perceptions regarding their role as mentors in the education system. They felt that they had the foundations for optimal mentoring as they are capable of providing a good response to the needs of novice teachers and the tools to mentor them: coordinating expectations with the novice teacher was perceived as important, their areas of responsibility as mentors were clear to them, their work is satisfying, they feel that the school supports their work, and they recommend acting as mentor teachers to others. Moreover, the participants clearly perceive their role as contributing to a moderate degree to their professional development as mentors: developing instruction skills and improving their skills of reflection, which improves the quality of their own teaching. They also note that they learn from the novice teacher whom they mentor. Most of the mentor teachers claimed that their status at the school did not change as a result of this role. They also noted that they did not receive suitable training for mentoring novice teachers.

The fourth research question related to the nature of the encounters between the mentor teacher and the novice teacher. Most respondents (71.4%) reported that no set hour had been defined in the curriculum for meeting with the novice teacher and that the frequency of the encounters is also usually not constant. Accordingly, the mentor teachers reported that the encounters with the intern are planned only to a moderate degree. The needs of the novice teacher, the needs of the school, and predesigned plans were reported to have only a moderate effect on planning the encounters. The mentor teachers testified that, to a large degree, they have the professional ability and necessary tools to perform their mentor role optimally, with no negative impact on their other roles.

The fifth research question related to the capacity of the mentor teacher to operate effectively. Mentor teachers considered themselves very effective mentors, as manifested in their contributions to providing emotional support to the novice teacher and in advance the novice teacher in different aspects of their teaching practice by observing classes and providing evaluations. In addition, they felt moderately effective in leading novice teachers to independence and autonomy but less effective in integrating novice teachers into the institutional culture. This finding raises questions regarding the need for training for mentors. Although mentors in the Israeli education system are required to complete 60 h of training, only half of the teachers who serve as mentors actually participate in such training. As principals face a demand for mentors that greatly exceeds the supply of teachers who have completed mentoring training, teachers are frequently assigned as mentors even in the absence of training. The reality is that novice teachers are increasingly being mentored by teachers who are experienced but have no mentoring training.

In summary, the mentor teacher has an extremely important role in providing pedagogical support and emotional support to novice teachers, as, according to their reports, they have a considerable impact on novice teachers, mainly in the context of class management, imparting pedagogical knowledge, increasing novice teachers’ sense of belonging to the organization, integrating them into the school staff, and familiarizing them with the organizational culture. Most of the mentor teachers’ drive to choose the role of mentor derives from intrinsic motivations: the desire to contribute to the system.

6. Practical Implications and Research Suggestions

The research findings may have practical implications regarding the desired and effective mentorship model for training teachers in a technological era, where study spaces are diverse and allow for personal and group learning. The overall goal of the holistic mentoring model is to provide professional, pedagogical, and psychological support for novice teachers within the education system to ensure their integration and successful retention at their school.

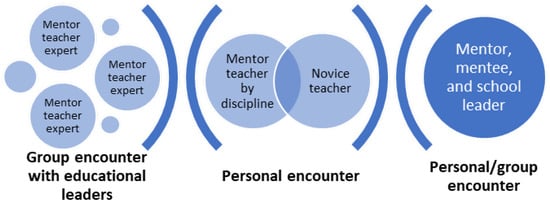

Therefore, the research suggestion is to build a model for holistic mentoring that is capable of coping with future challenges of teaching and learning. The current mentoring model applied in Israeli high schools today is based on weekly mentor–mentee meetings, and the majority of mentors are experts in the mentee’s discipline. In the holistic mentoring model we propose (see Figure 2), the mentee participates in: (a) weekly meetings with the mentor; (b) quarterly meetings with the mentor, and the school principal or deputy principal; and (c) in addition, the novice teacher is given access to several mentor experts, each with expertise in a different area (e.g., social–emotional support, classroom culture and management, professional development). In the holistic model, the mentor experts also conduct group meetings with all the novice teachers in the school who are interested in a specific topic such as leaders on emotional issues, communication, cultural issues, class management, and the school’s function as a unique study space. This model harnesses the advantages of a group process to deal with educational challenges, and the fact that the group serves as a significant source of social support, and affirmation that they are “not alone”. The group process has many advantages: participants learn that their peers encounter similar experiences and deal with similar challenges, they share ideas and advice from their own experiences, and receive several multiple responses. The holistic model is designed to resolve the shortcoming of the traditional model in which the mentor teacher does not have the knowledge and expertise in all dimensions of teaching necessary in the postmodern era.

Figure 2.

Holistic mentorship model for the postmodern era.

Education systems in the postmodern era strive to adapt the features of teaching and learning to the challenges of the 21st century. Accordingly, schools must meet the changing needs of novice teachers and establish features of innovative pedagogy that fit these challenges and transitions within training processes. Nonetheless, with regard to suitable practices for this era, the emphasis is on breaching the regularities of study spaces, encouraging initiatives among novice teachers, and using diverse teaching methods that promote active, differential, experiential, and reflective learning. Most of these practices have been described with regard to forming the professional identity of novice teachers.

This holistic model has two underlying principles. The first is to support the professional learning processes of novice teachers, which will include innovative pedagogy and constitute, by virtue of their very existence, a model for learning in the 21st century while generating professional learning communities. The second is to provide organizational support for innovative teaching and learning processes regarding emotional, physical, and structural resources while legitimizing and supporting teaching that transcends time and place. The following subsections delineate the tasks of mentor teachers within each dimension of the holistic model.

6.1. Mentor Teachers for the Dimension of School Culture and Class Management

- Class management: Establishing and maintaining a positive class environment, developing efficient routines, procedures, and strategies for managing student behavior and promoting involvement, and creating a safe and containing study space.

- School policy and regulations: Familiarizing novice teachers with the school’s policy, regulations, and expectations, assisting with understanding administrative demands such as attendance, grades, and reports, and instructing novice teachers on navigating administrative systems and processes.

- Understanding the pay slip and benefits: Assisting novice teachers with understanding the pay structure, deductions, and payroll schedule and explaining the benefits package, including healthcare services and retirement plans, expense reimbursement, and other administrative tasks related to compensation.

- Forming networks and professional collaboration: Encouraging novice teachers to participate in professional learning communities within the school and externally and to form ties with other educators or professional organizations for networking opportunities, promoting cooperation, and sharing ideas among colleagues to nurture a supportive learning environment.

6.2. Mentor Teachers by Discipline

- Curriculum and guidance: Understanding the curriculum and the school’s regulations, planning and preparing lessons, providing distinctive guidance to meet the needs of diverse students, applying efficient teaching strategies and techniques, and integrating technology and digital tools into the lessons.

- Evaluation and feedback: Designing formative and summative assessments, analyzing teaching evaluation data, providing students with timely and constructive feedback, and developing strategies for addressing student misconceptions and promoting growth.

- Self-reflection and growth: Instructing novice teachers on engaging in self-reflection and self-evaluation of their teaching methods, assisting with setting personal and professional goals for constant improvement, and encouraging novice teachers to ask students, colleagues, and principals for feedback to improve their teaching practices.

6.3. Mentor Teachers for the Emotional-Communication Dimension

- Professional ethics and dilemmas: Discussing ethical considerations and professional standards in education, instructing the novice teacher on navigating ethical dilemmas and reaching fundamental decisions, sharing experiences and personal points of view to help the novice teacher develop professional discretion, and providing insights on maintaining professional boundaries and addressing emotional situations.

- Individually adapted student support: Identifying and relating to the student’s needs and individual learning styles, implementing strategies for students with special education needs, and cooperating with other professionals such as special education teachers and counselors.

- Parent and community involvement: Developing strategies for effective communication with parents and guardians, building positive relationships with parents and including them in their child’s education, encouraging involvement with the local community, and utilizing community resources.

6.4. Mentor Teachers for the Professional Development Dimension

- Managing time and organizing: Helping novice teachers develop efficient time management strategies to balance responsibilities for teaching, planning, grading, and professional development, providing tips and techniques for organizing materials, resources, and paperwork in class, and assisting with prioritizing tasks and defining realistic goals to reach full productivity.

- Professional development and growth: Identifying relevant professional-development opportunities, supporting novice teachers in setting professional goals, assisting with forming a professional development plan, and encouraging reflection and self-evaluation for constant improvement and the development of initiatives and innovativeness.

- A work–life balance and teacher well-being: Promoting self-care methods and strategies for managing stress, balancing the workload, maintaining a healthy work–life balance, providing emotional support, and creating a positive teacher community.

6.5. Leader of the Mentor Teachers and Novice Teachers

- Mentorship and emotional support: Building a mentoring relationship based on trust and open communication, actively listening to the concerns, challenges, and frustrations of the novice teacher, providing emotional support in hard times and helping the novice teacher cope with stress and burnout, providing encouragement and motivation, and increasing confidence and resilience.

6.6. Summary

In recent years, teacher training has been coping with changes and reforms deriving from the discourse on the need for educational innovation [51], as well as from technological, social, and cultural changes and structures typical of postmodern society. The information revolution and life in a frequently changing environment are challenging the education system, which must adapt to these changes to prepare students for the future employment world and equip them with the skills they will need to become active and responsible citizens involved in a complex world of uncertainty [52]. In the educational field, these changes are described in terms of a transition in the teaching and training of novice teachers from a traditional and hierarchal structure to teaching, training, and mentorship based on learning communities, where learners collaborate regarding challenges in the school system and the study contents and generate knowledge [53].

Mentorship is intended to support the professional development of novice teachers while providing support in the initial stages of the novice teacher’s professional career [54]. At the same time, mentorship has great potential as a channel for lifelong development. The proposed holistic model is designed to provide a flexible learning environment that nurtures creativity, initiative, and critical thinking and encourages learners to be active producers of knowledge with self-direction and the ability to solve their problems throughout life [55]. The model indicates three main support mechanisms (organizational, professional, and emotional), operated by a network of role partners who are leaders in the school community, including the principal and management, teacher colleagues, and mentor teachers. Such a model might help novice teachers improve their status at the school, develop a sense of belonging to the organization, and increase their motivation to remain in the teaching profession.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.D.; Methodology, M.B.-A.; Resources, M.B.-A.; Writing—original draft, N.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics committee for non-clinical studies in humans (AU-SOC-MBA-20230327 27.3.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Izadinia, M. Student teachers’ and mentor teachers’ perceptions and expectations of a mentoring relationship: Do they match or clash? Prof. Dev. Educ. 2016, 42, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, H.L.T. Understanding mentoring within an ecosystem of practices. In New Teachers in Nordic Countries—Ecologies of Mentoring and Induction; Olsen, K.-R., Bjerkholt, E.M., Heikkinen, H.L.T., Eds.; Cappelen Damm Akademisk: Oslo, Norway, 2020; pp. 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Orland-Barak, L.; Hasin, R. Exemplary mentors’ perspectives towards mentoring across mentoring contexts: Lessons from collective case studies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, M.; Gupta, K.S. Transformational leadership: Emotional intelligence. SCMS J. Indian Manag. 2015, 12, 75. [Google Scholar]

- Carver-Thomas, D.; Darling-Hammond, L. Teacher Turnover: Why It Matters and What We Can Do about It. Available online: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Teacher_Turnover_REPORT (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Van der Spoel, I.; Noroozi, O.; Schuurink, E.; van Ginkel, S. Teachers’ online teaching expectations and experiences during the Covid19-pandemic in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronfeldt, M.; McQueen, K. Does new teacher induction really improve retention? J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 68, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canipe, M.M.; Gunckel, K.L. Imagination, brokers, and boundary objects: Interrupting the mentor–preservice teacher hierarchy when negotiating meanings. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 71, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeraerts, K.; Tynjälä, P.; Heikkinen, H.L.; Markkanen, I.; Pennanen, M.; Gijbels, D. Peer-group mentoring as a tool for teacher development. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 38, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsyuruba, B.; Godden, L. The role of mentoring and coaching as a means of supporting the well-being of educators and students. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 2019, 8, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelchtermans, G. ‘Should I stay or should I go?’: Unpacking teacher attrition/retention as an educational issue. Teach. Teach. 2017, 23, 961–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P. Forming the mentor-mentee relationship. Mentor. Tutoring 2016, 24, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz-Oppenheimer, O. Being a mentor: Novice teachers’ mentors’ conceptions of mentoring prior to training. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2017, 43, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano, J.E.; Farver, S.D.; Guenther, A.; Wexler, L.J.; Jansen, K.; Stanulis, R.N. Reflections from the room where it happens: Examining mentoring in the moment. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 2019, 8, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, L.U. Educative mentoring: Promoting reform-based science teaching through mentoring relationships. Sci. Educ. 2010, 94, 1049–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiman-Nemser, S. Multiple meanings of new teacher induction. In Past, Present, and Future Research on Teacher Induction: An Anthology for Researchers, Policy Makers, and Practitioners; Rowman & Littlefield Education: Lanham, MD, USA, 2010; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Feiman-Nemser, S. What new teachers need to learn. Educ. Leadersh. 2003, 60, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Spooner-Lane, R. Mentoring beginning teachers in primary schools: Research review. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2017, 43, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoCasale-Crouch, J.; Davis, E.; Wiens, P.; Pianta, R. The role of the mentor in supporting new teachers: Associations with self-efficacy, reflection, and quality. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 2012, 20, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, M.A. Person and context in becoming a new teacher. J. Educ. Teach. 2001, 27, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenschmidt, E.; Oder, T. Does mentoring matter? On the way to collaborative school culture. Educ. Process 2018, 7, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artman, B.; Crow, S.R. Instructional technology integration and self-directed learning: A dynamic duo for education. Int. J. Self Dir. Learn. 2022, 19, 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J.; Lawson, T.; Wortley, A. Facilitating the professional learning of new teachers through critical reflection on practice during mentoring meetings. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2005, 28, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanks, R.; Attard Tonna, M.; Krøjgaard, F.; Annette Paaske, K.; Robson, D.; Bjerkholt, E. A comparative study of mentoring for new teachers. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2022, 48, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, S. Understanding beginning teacher induction: A contextualized examination of best practice. Cogent Educ. 2014, 1, 967477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinge, C.M. A conceptual framework for mentoring in a learning organization. Adult Learn. 2015, 26, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spezzini, S.; Austin, J.S.; Abbott, G.; Littleton, R. Role reversal within the mentoring dyad: Collaborative mentoring on the effective instruction of English language learners. Mentor. Tutoring 2009, 17, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štemberger, T. The teacher career cycle and initial motivation: The case of Slovenian secondary school teachers. Teach. Dev. 2020, 24, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembytska, M. Supporting novice teachers through mentoring and induction in the United States. Comp. Prof. Pedagog. 2015, 5, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zinsser, K.M.; Curby, T.W. Understanding preschool teachers’ emotional support as a function of center climate. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 2158244014560728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Tal, S.; Chamo, N.; Ram, D.; Snapir, Z.; Gilat, I. First steps in a second career: Characteristics of the transition to the teaching profession among novice teachers. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 660–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavish, B.; Friedman, I.A. Expectations of pre-service teachers as organizational personnel: Collegial professional work environment, recognition, and respect. Hahinuch Bemivhan 2005, 2, 132–155. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Hall, K.M.; Draper, R.J.; Smith, L.K.; Bullough, R.V., Jr. More than a place to teach: Exploring the perceptions of the roles and responsibilities of mentor teachers. Mentor. Tutoring 2008, 16, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillel-Lavian, R. Masters of weaving: The complex role of special education teachers. Teach. Teach. 2015, 21, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbiv-Elyashiv, R.; Donitsa-Schmidt, S.; Zuzovsky, R. School Features that Facilitate or Delay the Induction and Retention of New Teachers in the Education System: Research Report; Kibbutzim College: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2019. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Kremer, K.P. Burned out and dissatisfied? The relationships between teacher dissatisfaction and burnout and their attrition behavior. Elem. Sch. J. 2022, 123, 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, J. Encouraging retention of new teachers through mentoring strategies. Delta Kappa Gamma Bull. 2016, 83, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fresko, B.; Nasser-Abu Alhija, F. Induction seminar as professional learning communities for beginning teachers. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2014, 43, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavelevsky, E.; Lishchinsky, O.S. An ecological perspective of teacher retention: An emergent model. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 88, 102965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Peretz, M.; Schonmann, S. Behind Closed Doors: Teachers and the Role of the Teachers’ Lounge; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Algozzine, B.; Gretes, J.; Queen, A.J.; Cowan-Hathcock, M. Beginning teachers’ perceptions of their induction program experiences. Clear. House 2007, 80, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, L.J. Working together within a system: Educative mentoring and novice teacher learning. Mentor. Tutoring 2019, 27, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ginkel, G.; Verloop, N.; Denessen, E. Why mentor? Linking mentor teachers’ motivations to their mentoring conceptions. Teach. Teach. 2016, 22, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gultekin, H.; Acar, E. The intrinsic and extrinsic factors for teacher motivation. Rev. Cercet. Interv. Soc. 2014, 47, 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesnut, S.R.; Burley, H. Self-efficacy as a predictor of commitment to the teaching profession: A meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, M.C.; Valtierra, K.M. Enhancing preservice teachers’ motivation to teach diverse learners. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 73, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsko, K.K.; Ronfeldt, M.; Nolan, H.G. How different are they? Comparing teacher preparation offered by traditional, alternative, and residency pathways. J. Teach. Educ. 2022, 73, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orland-Barak, L. Mentoring. In International Handbook of Teacher Education; Loughran, J., Hamilton, M.L., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 105–141. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, G.; Yost, D.; Conway, T.; Magagnosc, A.; Mellor, A. Using instructional coaching to support student teacher-cooperating teacher relationships. Action Teach. Educ. 2020, 42, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debs, L.; Miller, K.D.; Ashby, I.; Exter, M. Students’ perspectives on different teaching methods: Comparing innovative and traditional courses in a technology program. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2018, 37, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Hyler, M.E.; Gardner, M. Effective Teacher Professional Development; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Poyas, Y. (Ed.) Teacher Education in the Maze of Pedagogical Innovation; Mofet Institute: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2019. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Schatz-Oppenheimer, O. Mentoring—Theory, Research, and Practice; Resling: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2021. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).