Abstract

Digital transformation has become constant and has forced governments to reevaluate the validity of their educational models; therefore, regarding digital and information literacy, to train teachers to improve new digital skills becomes essential. For these reasons, this research will explore the instruction of teachers in digital and information literacy in basic education; likewise, there will be an observation of the research’s theoretical-methodological characteristics related to these variables, and, also, we will carry out an analysis of the most pertinent contributions on the impact of new literacies and competencies in the teaching–learning processes in basic education, with the purpose of obtaining a current state overview of its teacher training within the framework of the technologies’ usage linked to teaching. This review was based on the guidelines of the PRISMA protocol, and to select 56 documents, the Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) databases were used. The results show that, in the Scopus database, Spain is the country with the most research on the subject, with 29% of the total, followed by Indonesia, with 6%, and the United States, with 4%, and that the articles focus mainly on the social sciences and computer science. Likewise, in WoS, the country with the most research on the subject is Spain, with 30%, followed by Russia, with 10%, and Norway, with 8%, and the articles mainly revolve around the categories of education and communication. The research related to this topic uses a quantitative approach in 68%, a qualitative approach in 25% and a mixed approach in 7%. It was shown that there is a direct relationship between digital and information literacy and digital competency. In addition, it is also emphasized that digital and information literacy are continuous and long-term processes. More didactic proposals on digital skills would be necessary, over government policies and efforts, to achieve a community with a high level of digital and information literacy.

1. Introduction

During the last three years, educational institutions worldwide have undergone a transformative process, mainly those of public management [1], due to the influence of digitization in the teaching and learning processes mediated by the growing digital services offered to today’s users [2]. During the digital era, teachers, students and senior management have access to various technologies and digital resources for academic and cultural exchanges to meet current and future challenges [3,4] which forces governments to reevaluate the validity of their educational models. The term “digital literacy” is linked to a set of skills or competencies needed in the digital era, and is associated with a solid knowledge of the digital world [5] where technology goes beyond simply sending messages via email or creating and using social networks such as Facebook, Twitter (X) or Instagram. To be innovative and remain competitive, digitalization must be integrated into education [6]. Thus, digital literacy, in this study, is used to encompass a wide range of skills and knowledge needed to make effective use of digital tools [7], which teachers must possess in order to make effective use of digital tools by incorporating them into their didactic–pedagogical work, where they develop teaching–learning strategies with technology and have a favorable relationship with them [8].

The accelerated development of the changing information and communication society demands from its citizens necessitates skills that allow them to access and adapt to the diverse situations they may face [9]. This accelerated advance in Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) has changed the lifestyles of children, adolescents, young people and adults [10], and leads to permanent changes in the educational, cultural, economic and social spheres, thus requiring citizens to constantly change in order to adapt to new circumstances [11], leaving older adults behind, as they do not have the tools, knowledge and learning speed necessary to effectively integrate these changes [12,13]. In addition, there is a need for technological training for teachers in aspects related to the attention to student diversity, where factors such as the age of the teaching staff are an obstacle when facing the technological challenges presented by ICT [14].

Thus, the proliferation of ICT in our daily lives generates great interest in its application to education [15]. Therefore, today it is not only of interest to understand how knowledge acquisition occurs and how much the use of digital technologies influences learning processes [16,17], but also what competencies should be incorporated into local, regional and global educational efforts. In a framework of accelerated change, 21st century teachers face important challenges generated by the accelerated development of artificial intelligence (AI), virtual reality (VR) and the massification of social, economic and cultural relations mediated by the Internet. In this sense, society revolves around a new paradigm of communication mediated by the use of the network and the Internet, which is seen as another revolution for humanity [18].

On the other hand, the pandemic generated by the massive contagion of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has forced an urgent change in the realities of educational institutions [19] and accelerated the abandonment of traditional ways of “teaching” to give way to active methods mediated by digital environments. The COVID-19 pandemic changed the way education is conducted, not only in the moment that the face-to-face model was replaced by a virtual one, but also in the period of the return to normality because the digital skills of teachers are no longer the same as before [20]. In this new normal, government institutions made countless efforts to design and create virtual learning scenarios that had the Internet as their main support. For example, with Spain, institutions migrated to an online structure, prioritizing audiovisual language and distance communication; due to such considerations, it is possible to affirm that teachers at all levels of education across the world experienced a forced transition from face-to-face work to two modalities—synchronous and asynchronous—which were unusual until 2020 but imply an optimal use of technology [21].

So, as a consequence of the incorporation of ICT in training processes, the pandemic and recent concerns about educations based on uncertainty, interest in adopting approaches based on digital and media competencies is growing, allowing them to meet the new requirements of the knowledge of the information society [22]. According to [23], it is critical to assess and discuss the levels of digital competence and digital literacy that students and teachers achieve in order to create educational policies that are tailored to the needs of their environment. Following this concern, it is possible to find some studies that have already analyzed and comprehended the characteristics of digital and information literacy, and seek to respond to the demands of the knowledge society, enhancing the use of technology in education [24,25,26], but they leave some gaps in delimiting terms such as: digital literacy, digital competence, information literacy, informational competence, and so on [27].

As an important part of this research, a semantic approach to various groups of words that relate to our research topic—digital literacy, information literacy, and digital competence—will be taken. First off, according to a number of authors, digital literacy (DA) is a term that refers to the combination of various competencies that have been part of the agenda of a large number of educational institutions during the last ten decades: computer literacy, information literacy and media literacy [28,29]. Within this group of terms, semantic relationships can be established, taking into account the cognitive capacities and abilities involved. Secondly, digital competence refers to the skills of 21st-century citizens who use information networks; so, it can be determined that this makes up a component of digital literacy [5]. Moreover, informational competence, as a generalized concept, brings together the abilities, knowledge and skills of the students to face the critical understanding of messages and any information they receive through the media and from sources specific to the digital world; Thirdly, digital competence is inserted into the categories of digital literacy and information literacy [30].

This review seeks to do the following: explore teachers’ training in digital literacy, information literacy, and digital competence in basic education; observe the theoretical-methodological characteristics of research related to digital and information literacy; carry out an analysis of the most pertinent contributions about the impact of digital and information literacy on teaching–learning processes in basic education; and acquire an overview of the current state of teachers’ training concerning digital and information literacy and digital competence to identify gaps and needs in basic education. The general question: what are the most relevant characteristics, contributions, shortcomings and needs of the scientific production on digital and information literacy in basic-education teaching staff?

In this regard, the review will concentrate on the following research objectives:

- -

- OBJ01: Present the theoretical and methodological characteristics of research related to digital and information literacy and digital competence;

- -

- OBJ02: Analyze the most relevant contributions about the impact of digital and information literacy on teaching–learning processes in basic education;

- -

- OBJ03: Analyze the current state of teacher training in relation to digital and information literacy and digital competence to identify gaps and needs in basic education.

The structure of the document comes from the definition of the objectives; therefore, the methodology used in the review process is presented next. Subsequently, the results section aims to achieve the objectives based on the selected articles. The discussion and conclusions regarding teacher training concerning digital literacy, information literacy and digital competence are presented last.

2. Materials and Methods

For this systematic review work, an analysis of the international scientific production found in the Scopus and WoS academic databases has been carried out, which will guarantee the quality and scientific rigor of the work carried out.

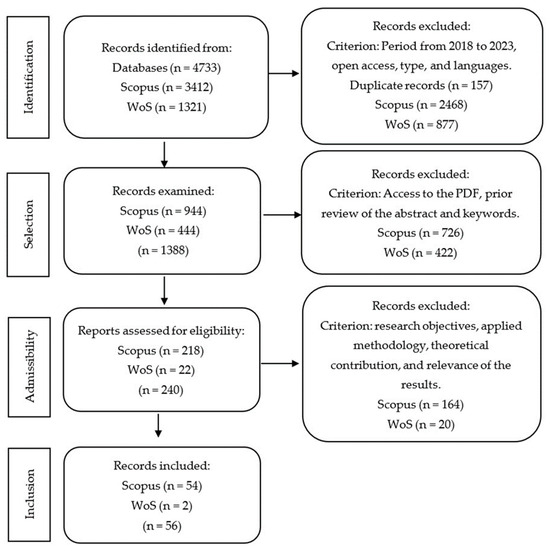

This review was based on the guidelines and strategies proposed in the PRISMA protocol. In an initial search, 4733 articles were found, of which 3412 belong to the Scopus database and 1321 to the WoS.

After an exhaustive analysis, 56 articles were selected to work with, 54 belonging to the Scopus database and 2 to WoS, based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

The inclusion criteria are the following:

- -

- Spanish and English language;

- -

- Open access;

- -

- Articles with full text;

- -

- Type: articles and conference papers;

- -

- Works published in the period 2018 to 2023 (April).

- -

- Regarding the exclusion criteria:

- -

- Other systematic reviews were not considered;

- -

- Articles that develop research on the study variables in other areas;

- -

- In the case of the WoS database, Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) publications and health sciences categories were not considered.

It should be noted that the studies were grouped based on the categories (digital literacy, digital competence, information literacy, media literacy and digital media) and the research objectives set out for their synthesis.

For the data extraction process, the search equation used the descriptions, detailed in Table 1, and the Boolean operators AND and OR, shown in Table 2. It should be noted that the search in both databases was carried out only with the English descriptors. In addition, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied and the results from both databases were integrated into a single paper. For the treatment of missing data, each study was checked in its original source for completeness of metadata and reliability.

Table 1.

Search descriptors.

Table 2.

Search equations.

The final selection of the articles was based on four steps: identification, selection, admissibility and inclusion, as summarized in Table 3, and the flow chart of the applied methodology is shown in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Database and steps developed to obtain the information.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Taking into account the criteria in each step and the objectives of the research, each researcher proceeded to read the studies, using the notes in the same documents, where the most relevant data of the studies was found, and a data analysis template elaborated on in Microsoft Excel to be used in the synthesis of the results were consigned.

In addition to the Excel spreadsheet, the Zotero bibliographic management tool was used, and the VosViewer tool was used for the bibliometric analysis.

Following the PRISMA protocol, Step 1, identification, included searching for information on the object of study based on the following criteria: The period from 2018 to 2023 (April), open access, type (article and conference paper) and the languages, Spanish and English. It also integrated the results and eliminated duplicate records found.

In Step 2, selection, the eligibility criteria were based on access to the pdf and a prior review of the abstract and keywords of each paper.

In Step 3, admissibility, the criteria taken into account included the following: research objectives, applied methodology, theoretical contribution and relevance of the results. All authors participated and independently analyzed the articles, and the information was then cross-checked to avoid selection bias.

Step 4, inclusion, shows the selected articles, whose content analysis took into account the objectives and variables set out in this research as a method of synthesis, and is shown in the results section.

The analysis variables collected from each article include information such as: country, keywords, category, methodology (quantitative/qualitative/mixed), sample (participants), instrument/technique and important results.

Descriptive statistics were used for the summary statistics using the Excel spreadsheet, complemented with the bibliometric analysis using the Vos-Viewer tool.

The risk of bias is considered minimal, due to the language, because only Spanish and English have been considered, as this is where the largest amount of research on the topic under study is concentrated; and, finally, only the two main databases, Scopus and WoS, have been taken into account, given that they concentrate the largest number of publications related to the topic under study.

3. Results

3.1. OBJ01: The Theoretical-Methodological Characteristics of Research That Are Related to Digital and Information Literacy and Digital Competence

The theoretical characterization of the analyzed research is presented:

3.1.1. The Thematic Areas Addressed

As seen in Table 4, most research has a predominance in the thematic area of digital competence (50%), in the digital literacy area (33.9%). Furthermore, a small percentage of research related to information literacy (16.1%) was found.

Table 4.

Thematic areas addressed.

There is an inclination to work on topics related to digital competence, given the need to provide teachers at all educational levels with training that enables them to include technologies in their pedagogical practice.

3.1.2. The Evolution of Digital Competence

Information and communication technologies (ICT) are an instrument that supports new ways of teaching, learning and acquiring skills, which have their origin in the world of work, transcending the academic world to train and educate people to access and develop in a globalized society. Therefore, it is necessary for teachers to acquire competencies to develop in technological environments by renewing contents and pedagogical methods in symbiosis [31]. In this way, the development of ICT has revolutionized society and the educational field, highlighting the need to provide teachers at different educational levels with training where they are instructed to include technologies in a relevant, critical and reflective manner in their pedagogical practice [32]. It is necessary to change the teacher training process. Thus, on 18 December 2006, within the framework of the Recommendation of the European Parliament and the Council, digital competence was considered one of the eight key competencies for life and lifelong learning. This leads to introducing the competency-based educational approach to training, which leads to proposing mechanisms that transform teaching and learning where technological tools are used, so that the pedagogical practices offer contextualized teaching that eliminates gaps between education and society.

A techno-pedagogical update of ICT skills and knowledge is being promoted among teachers under this techno-educational scenario. In this line of competency argument, the National Institute of Educational Technologies and Teacher Training (Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas y de Formación del Profesorado) (INTEF), with the intentional desire to regularize and normalize professional competency skills at a technological level that a teacher must possess in current education, has established five areas that link digital competence. These are collected as follows. Digital competence, having five competence areas: (1) computerization and information literacy; (2) communication and elaboration; (3) the creation of digital content; (4) security; and (5) problem-solving, [32].

3.1.3. The Evolution of the Concept of Digital and Information Literacy

The conceptualization of the term digital literacy is based on three key conceptions: The first concept was used in 2001 by Prensky, who coined the phrase “digital natives” when pointing out today’s students who speak the digital language of computers, video games and the Internet. In this approach, he claimed digital natives are students who are born with a natural ability to use technology.

The second conceptualization is proposed in 1997 by Gilster, who coined the term “digital literacy” as a compilation of interrelated skills or competencies required for survival in the digital age. This is one of the most popular meanings of the term. According to the author, digital literacy refers to a set of skills related to reading and understanding multimedia and interactive texts, collecting information, sharing information collaboratively and locating and evaluating information from digital sources. Since Gilster proposed his competency-based concept, many models and ontologies have contributed to the understanding of the skills that students would need in the Internet era. In 2004, Eshet-Alkalai proposed a conceptual framework for digital literacy, defining it as a collection of five literacies: reproductive literacy, information literacy, photo-visual literacy, socio-emotional literacy and branching literacy.

The third conceptualization that many scholars are actively discussing is the soci-ocultural perspective of digital literacy. Sociocultural perspectives place a strong emphasis on the literacy aspects of digital literacy and, as a result, perceive digital literacy as as-sociated with the active participation of students in the realm of online communities. In 2006, Knobel and Lankshear defined a sociocultural vision of digital literacy as the involvement of students in established ways of generating, exchanging and negotiating pertinent content as members of narratives through coded texts.

In this way, various studies demonstrate that digital literacy is a long-term, ongoing process. It takes more than government policies and efforts to achieve a digitally literate community. In this regard, several community developments programs and initiatives have been started and implemented to educate communities on digital literacy. To fully integrate Web 2.0 and 3.0 technologies across the board in the digital literacy curriculum requires the training of teachers in how to educate students with a considered and re-sponsible approach to handling ICT [33].

3.1.4. Summary of Selected Scientific Production

Table S1 [27,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85] summarizes the 56 selected articles in the following fields: database, author, country, keywords, category, methodology, sample, instrument/technique and results.

3.1.5. Concepts Related to Digital and Information Literacy

Table 5 summarizes a synthesis of the concepts associated with digital and information literacy, guiding the reader to consider the language inherent to the process studied and its most important features.

Table 5.

Thematic areas addressed.

3.1.6. References Cited

Regarding the references consulted, it is clear that all the research analyzed has a bibliographic reference that includes a considerable number of authors. It should be noted that in each investigation, the number of references varies, but it can be specified that the approximate average is 20. Additionally, it was discovered that, in all the articles analyzed, in the bibliographic reference, there was an appropriate use of APA standards, which have been more systematized in research in recent years.

3.1.7. A Bibliometric Analysis of the Preliminary Search of Scientific Output

In the preliminary search for a bibliometric analysis of digital literacy and information literacy in basic-education teacher training, the following was found in the Scopus (n = 944) and WoS (n = 444) databases.

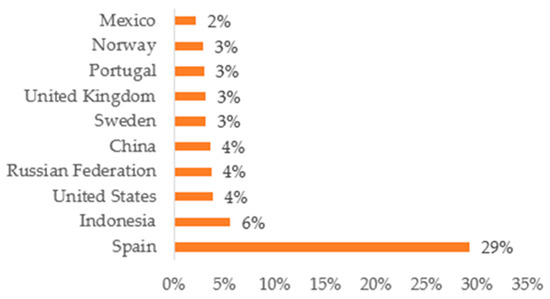

Scientific output by country from the Scopus database

In the analysis of the Scopus results (Figure 2), it was identified that Spain is the country with the most research on the subject of analysis, representing 29% of the total, followed by Indonesia with 6%, the United States, Russia and China with 4%, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Portugal and Norway with 3% and finally Mexico with 2%.

Figure 2.

Results of articles by country from the Scopus database.

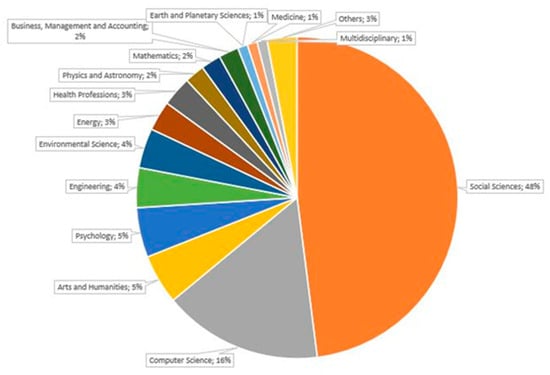

Scientific production by subject area in the Scopus database

These articles focus on two large thematic areas: 48% in Social Sciences and 16% in Computer Sciences, 5% in Arts and Humanities, as well as Psychology, 4% in Engineering and Environmental Sciences and 3% in Energy and Health Professions, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Results of articles by thematic area from the Scopus database.

The Scientific production of the WoS database category

Regarding the results of the WoS database, of the 444 articles found in the initial search by category, Table 6 shows that 270 articles focus on educational research, followed by 75 articles in the communication area; 20 in Environmental Sciences and Information Sciences Library Science; and 17 in Interdisciplinary Social Sciences.

Table 6.

Articles by category from the WoS database.

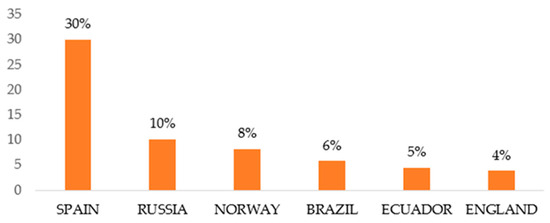

Scientific output by country from the WoS database

In the analysis by country, Figure 4 shows that in WoS, Spain leads with 30%, followed by Russia with 10%, Norway with 8%, Brazil with 6%, Ecuador with 5% and England with 4%.

Figure 4.

Articles by country from the WoS database.

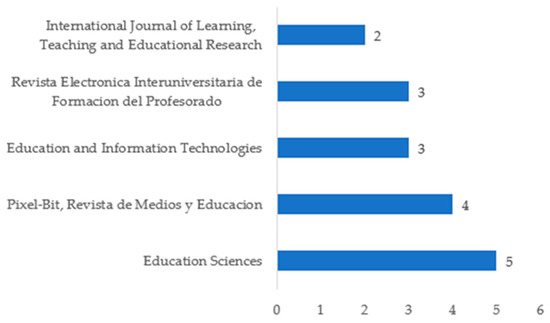

Number of articles per journal

Figure 5 shows the journals which concentrate the 56 selected articles, and in first place is the journal Education Sciences (5), followed by Pixel Bit (4), Education and Information Technologies (3), Revista electrónica Interuniversitaria de formación del profesorado (3) and finally Comunicar (2):

Figure 5.

Number of articles per journal.

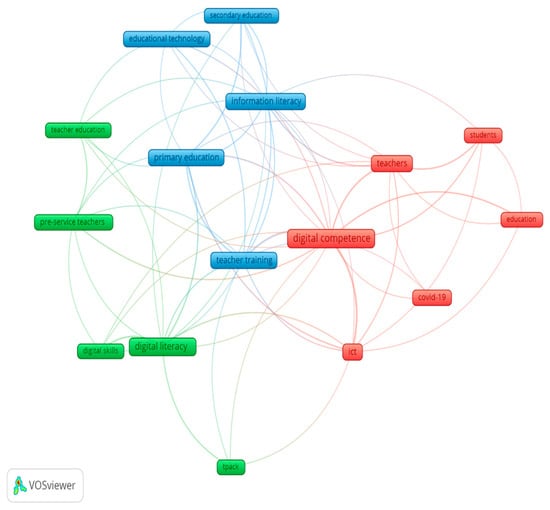

An Analysis of occurrence by keyword

In a more exhaustive analysis based on the keywords of the selected articles, Figure 6 shows where three clusters have been formed related to the two variables of the study: digital literacy corresponds to the green cluster, and information literacy corresponds to the blue cluster. But, it is important to highlight that these variables are related to a third generated cluster, the digital competence variable, which corresponds to the red cluster.

Figure 6.

Analysis of occurrence by keywords. VOSviewer version 1.6.19.

The green cluster, digital literacy, is closely related to teacher education, teachers in training, digital skills, and TPACK (Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge), a model which integrates technology in education.

Regarding the blue cluster, information literacy, it is related to primary education, secondary education, teacher training, and educational technology.

Finally, the red cluster, digital competence, is related to the variables under study; explained in the green and blue cluster, it integrates variables such as teachers, students, education, ICT and COVID-19.

It is evident that, to achieve digital and information literacy, teachers must strengthen their digital skills; consequently, the generation of more training opportunities will reduce the existing gaps that would benefit students and raise the quality of education.

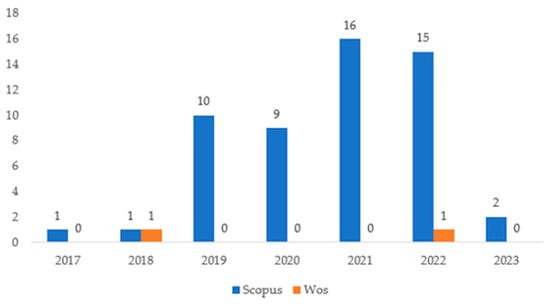

3.1.8. The Diachronic Quantification of Scientific Production on the Digital and Information

Literacy of Basic-Education Teachers

The scientific production about the object of the research is identified in the Scopus (n = 54) and WoS (n = 2) databases from the years 2017 to 2023. Figure 7 shows that the research was scarce in the years 2017 and 2018, with one production per year, increasing in the years 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022, with 10, 9, 16 and 15 publications reaching their highest peaks in the years 2021 and 2022, years after the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to note that in 2023, only two productions were considered, because this research ended in April 2023, which explains why there is a decline in scientific production this year.

Figure 7.

Scientific production per year.

The selected scientific production comes from 24 countries (see Figure 8), of which Spain (9) is the highest, followed by Malaysia (2), Switzerland (2), Turkey (2), Kenya (2), Indonesia (2), Brazil (1), Mexico (1), Germany (1), the United Kingdom (2), the Czech Republic (1), Sri Lanka (1), Portugal (1), New Zealand (1), the Philippines (1), Northern Ireland (1) and the Netherlands (1). In Latin America, only Peru and Brazil are the countries that make contributions to this thematic field. The country with the greatest influence on publications is Spain, with 30% of the total articles selected. The most frequently used database is Scopus, with 96.4% of all scientific production, and the least frequently used is WoS, with 3.6%.

Figure 8.

Scientific production by country grouped by continent.

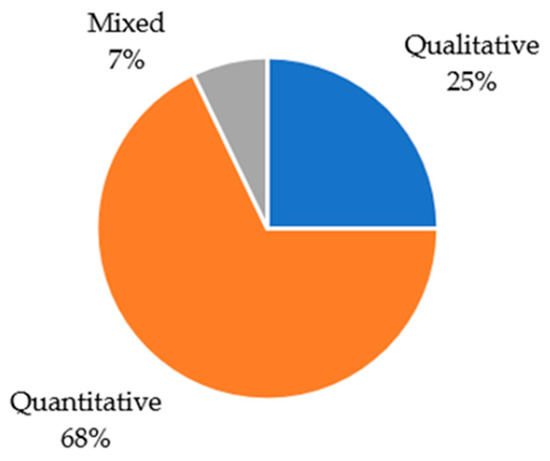

Figure 9 shows the research approaches that were examined in the analyzed studies. Following the pragmatic research approach, it reveals that the predominant research approach is quantitative (68%), followed by qualitative (25%) as well as mixed (7%).

Figure 9.

Research approaches.

Additionally, the outstanding type of research is the descriptive–propositive (61%) type, which comprises proposing training plans to raise the low levels of digital literacy in basic-education teachers. A total of 39% of the remaining works are only descriptive; they lack a proposal.

3.1.9. Instruments

According to the research analyzed, the instruments used to gather information were the following, which have been grouped into four sets:

- Ad hoc questionnaires, both structured and semi-structured, were used in 15% of the works;

- Question and/or discussion guides for interviewing were used in 43% of the works;

- The questionnaires were created and validated by various authors. A total of 25% of the investigations used validated questionnaires;

- A variety of infrequently used tools, comprising the Likert attitude scales (used in 15% of the investigations) and the technical sheet (2%).

3.2. OBJ02: The Most Relevant Contributions about the Impact of Digital and Information Literacy in Teaching–Learning Processes in Basic Education

According to the research analyzed, including technology in basic-education classrooms is a process of transformation that is having an impact on the educational process and on citizenship in general, in accordance with new circumstances, in which technology plays a fundamental role, and digital and information literacy is essential for citizens to develop fully in society.

In the first instance, this constitutes a pedagogical challenge, because teachers need to be digitally competent, and to do so, they must overcome a series of difficulties to enable them to become digitally and information literate, such as a lack of access to technological resources, insufficient skills to teach using technologies, a fear of not mastering technologies in their pedagogical work due to a lack of confidence in this methodology and because they have a low level of competence in digital skills [70] and the risk of students becoming bored with this way of learning [55].

In addition, the need for digital literacy for teachers in different age groups has been created [27]; the lack of teachers trained in digital and information literacy [35] must be addressed, due to the limited training provided to teachers or the poor quality of training provided to them. Institutionally provided training tends to be on occasional and inconceivable one-day or half-day courses, rather than through a more systematic continuous development program [37].

It has also generated the need for a transformation or evolution of the traditional conception of the term literacy, which is conceptualized in relation to what the information and knowledge society demands of a literate person [22].

It highlights the need for information literacy and research skills in teachers, which should be integrated into the ICT or alphabetization curriculum [34]. One way to empower individuals in an information society is to enable them to locate, select, use, process and transform information, so that they are able to use this information to achieve their professional, personal and educational goals. The need to strengthen teachers’ responses to difficulties in generating critical discourses based on Internet information about social problems has also been highlighted [48].

Several weaknesses can be identified in teachers, as well as in the initial/continuing training model, that contribute to the understanding of the difficulties encountered [41]. Teachers still need more training sessions that focus on the continuum of professional development [42].

The integration of technologies has led teachers to possess a mainly technical view of basic information literacy skills (how to use a search engine) and to overlook mental processes (the need or strategy for information) [47].

On the other hand, there is evidence of a favorable attitude towards teachers’ digital and non-formational literacy [65]; teachers perceive that their activities to foster communicative competences are currently integrated with ICT-related practices [67].

In turn, the importance of IT resources as tools that allow people to make decisions based on adequate and accurate information is emphasized. Currently, electronic media, computers, tablets and mobile devices are a resource through which it is possible to access libraries, information repositories and other sources of information, making ICT indispensable for improving the quality of education [23].

Likewise, many of them mention that teachers identified highly positive factors or effects from integrating Digital Educational Resources. To put it another way, teachers’ teaching approaches are based on currently available hardware and software, including Microsoft and Google, teaching materials, Internet resources and mobile device applications [28]. Additionally, it was discovered that, in accordance with the studies analyzed, the rapid evolution of the scientific production of knowledge suggests that, on the one hand, teachers choose MOOC education due to the convenience of distanced education [37].

Additionally, it was discovered that, at the Latin American level, there is a need to acquire digital knowledge and digital and information literacy for primary education teachers, based on different age groups [30]. It was also discovered that primary-level teachers have an optimal level of perceptions regarding the area of information, regardless of the type of school, as well as a prediction concerning the typology of some information literacy variables [39].

Likewise, it was also discovered that integrating Web 2.0 and 3.0 technologies into all areas of the digital literacy curriculum requires training teachers to instruct students with a deliberate and responsible approach to the use of ICT [33].

Finally, it should be noted that teachers have good awareness and attitudes towards the use of ICT in their daily work, but their educational practice is weak [74].

3.3. OBJ03: The Current State of Teacher Training concerning Digital and Information Literacy and Digital Competence to Identify Gaps and Needs in Basic Education

According to the analysis of the 56 selected investigations regarding teacher training, the majority showed that technological advancement had made it necessary for teachers to address the issues of technological literacy through the use of a variety of media and digital resources. These include the implementation of teacher training programs to provide them with tools and inputs that allow them to be digitally literate, one of which being the MOOC, thereby reducing the gaps and needs of basic education, since most studies reveal that the level of digital competence in basic-education teachers is low. The reasons cited by teachers for their low training do not refer to interest in ICT, but rather to this being a consequence of the absence of institutional support, time and resources, and the non-existence of training plans [42]; in some cases, due to teachers’ laziness and lack of training, it is crucial that the instrumental use given to technologies is overcome, and a more didactic, creative and as emotional use prevails [43]. Another issue that has been identified is that most institutional training comprises one-time or occasional, sporadic one-day or half-day courses, rather than a more systematic continuous development program; for this reason, a need arises to provide teachers at all levels with training that equips them to integrate technologies in their classroom methodology [32].

Additionally, the findings reveal that teachers have difficulty in creating critical discourses based on Internet information about social problems [44]. Likewise, the majority of studies mention the necessity for teachers to increase their level of digital competence through specialized training and the importance of creating public policies that will prepare them for a more digital school system.

When it comes to implementing ICT in the educational field, significant deficiencies are observed, sometimes due to laziness and a lack of training for teachers, since there is a need to provide them with training that prepares them to incorporate technologies in their classroom methodology [32,43]. As a result, it is crucial that the instrumental use given to technologies is overcome and a more didactic and creative use prevails; for this reason, in the present study, an analysis of the digital and information literacy of teachers of basic education is considered.

There are notable deficiencies in the implementation of ICT in education, due to the lack of preparation of teachers in the incorporation of technologies in their pedagogical work and teaching methodologies [32,43].

Despite the technological impact, research has shown that teachers lack the training and preparation necessary to carry out their functions effectively [31]. In this way, as pointed out, a gap is produced between students and teachers (the former being under-stood as natives and the latter as digital immigrants) [42].

On the other hand, teacher training has been carried out based on models emphasizing instrumental and technological aspects rather than pedagogical dimensions. It has been discovered that didactic training proposals for ad hoc teachers are also the object of study by educational theorists, who advocate for extrapolating examples tested in limited locations to larger and more culturally homogeneous areas. It should be noted that there are plans for voluntary digital literacy training, which include providing a group of students with resources and equipment to teach digital literacy to older people in their social environment.

4. Discussion

The carried out systematic review seeks to find the most recent information on research pertaining to digital and information literacy among basic-education teachers. For this, those documents related to the topic were selected, aiming to expose the theoretical–methodological characteristics of research that are related to digital and information literacy and digital competence, where the need for information literacy and search skills that must be integrated into the curriculum is observed, and there is an agreement on the significance of initial training for teachers to be able to educate basic-education students in a responsible approach to managing information and communication technologies [44,45,46,47].

One of the objectives of this article was to analyze the most pertinent contributions on the impact of digital and information literacy in the teaching–learning processes in basic education. We highlighted that institutional training in the topics of research in emerging lines such as digital and information literacy is important, and, when carrying out our review, we found that this need arises in different continents [48]. It requires citizens with the skills to access and adapt to the diverse situations they may face [9], in the educational, cultural, economic and social spheres [11]. We must strengthen individuals’ competencies linked to accessing information technologies to help them handle the technical issues that arise in educational work. In this regard, some noted in their research that, despite their confidence in their abilities, teachers’ understanding and information literacy (IL) skills are underdeveloped; this aspect does not surprise us, since we recognize the large amount of information that each teacher must deal with daily [49].

Similarly, the current state of teacher training was analyzed concerning digital and information literacy and digital competence to identify gaps and needs in basic education. We can conclude that teachers increase their level of digital competence through specialized training and the importance of developing public policies that prepare teachers for a more digital school system [50]. The spread of ICT in our daily lives generates great interest in its application to education [15]. Thus, teachers must incorporate the effective use of digital tools in their pedagogical work, where they develop teaching–learning strategies with technology and have a favorable relationship with them [8].

Currently, to be innovative and remain competitive, digitalization must be integrated into education [6]. Therefore, it is necessary to continue training teachers, since some have had to learn how to use various tools on their own, though we also had a percentage that still struggle to manage technology; mainly, older adults [14].

In our research, we demonstrate the importance that teachers place on Digital Educational Resources, both in their perception and practice [40]. This is another piece of research that supports the integration of this type of resource in the classroom, which plays an important role, as does the coordination and organization of the use of Open Educational Resources in the educational process. It is also emphasized that teachers identified positive factors or effects when integrating them into learning. This is another issue that we must take into account to ensure that all our students have unrestricted access to the different resources.

In the descriptive analysis of the selected articles, it was discovered that, during the pandemic, different articles have been written related to the research topic, which is associated with the need for teachers to improve their digital skills to face the virtuality of the teaching–learning process. For this reason, the effective management of digital skills is necessary for teachers, as well as managing strategies to energize their sessions [86].

Based on the findings, it is very important to understand that we must strengthen the digital skills of our teachers, particularly in everything related to digital and information literacy, such as searching for information, since in education, the Internet is used to look at different websites to provide solutions to different problems or needs. A number of weaknesses were identified in the digital competence of teachers, as well as in the initial or continuous training models [19,38,51]. On the other hand, the studies emphasize the need for the acquisition of digital knowledge for teachers, concluding that the difficulties are not only due to deficiencies in teacher training but also to a lack of infrastructure being revealed, mainly in the time of the pandemic, where the face-to-face teaching methodology was replaced by virtual learning [20].

The relevance of this article can be found in the compilation of different academic re-search on the digital and information literacy of basic-education teachers, where a number of weaknesses in the digital competence of teachers could be identified; this generates the need to attend training sessions for teachers [37,38,51,52,87]. Let us not forget that acquiring digital knowledge, for teachers, must accord with their level and age. For everything reviewed, we must keep in mind that a rapid evolution in the scientific production of knowledge is occurring. For this reason, teachers choose MOOC education, due to the convenience of distanced education and the progress that they can make at their own pace.

Many articles in the findings indicate that significant changes continue to occur in the integration of new technologies, but there is a need to continue to make teachers digitally literate. This is an extremely important point, as teachers need to develop their digital competencies for our students to benefit from them, which can be developed through training [27,35,37,38,43,44,49,53,55,56,58,65,71,73,74,75,76,77,79,81,83]. Different extracted studies generate gaps in the subject of digital and information literacy in basic-education teachers, which should be addressed in future research; we must take into account that, in basic education, we need teachers qualified in their area of study, despite the lack of teacher training in digital competency [32,33,37,46,48,50,68,72,78,82].

One barrier that we will encounter is the resistance to change of some teachers, after having gone through a pandemic which accelerated the process of adopting the use of new technologies and digital tools. There are still teachers who feel comfortable using traditional methods, as well as teachers who teach in different rural areas, who do not have access to new technologies and have difficulty using them [44,51,59,80].

5. Conclusions

Digital and information literacy in basic-education teachers is the topic of this systematic review, which compiled current the literature on the topic and discovered three approaches in the chosen scientific articles: 38 articles use the quantitative approach, 14 use the qualitative approach, and only four are mixed. Therefore, it is advised that, in future, work related to digital and information literacy use a quantitative approach complemented by a qualitative approach, given that both approaches contribute to research on teachers’ digital competencies.

The articles are found in five magazines: first, we have the magazine Education Sciences (5), followed by Pixel Bit (4), Education and Information Technologies (3), Revista electrónica Interuniversitaria de formación del profesorado (3), and finally Comunicar (2). A more thorough analysis was carried out based on the keywords of the chosen articles, forming three clusters related to the variables of the study, which were digital literacy and information literacy, highlighting that these variables are related to the digital competence variable.

Currently, the training of teachers’ digital competence regarding digital and information literacy in basic education is still in a precarious state, but important progress is being made, especially in Spain. This country, unlike the other nations, has incorporated empowerment strategies for the use of ICT in the training of basic-education teachers to ensure better and wider access to online-mediated education.

On the other hand, there is also a need to improve the abilities linked to managing massive information banks through teacher training programs. These measures would help improve the education of students at the basic-education level, without ignoring the fact that we have recently experienced a pandemic that sped up the use of technological tools in the teaching–learning processes. On the other hand, there is an emphasis in the significance of training teachers in digital literacy to increase their levels of confidence in the comprehension and information literacy skills, these being teachers who, according to some studies analyzed, are underdeveloped. Likewise, it is necessary to cover the need for information literacy and search skills to empower teachers to address educational problems brought about by the use of digital platforms.

Furthermore, this research will contribute to the advancement of the scientific area, as it provides information to research digital and information literacy in regular basic-education teachers.

For example, it would be interesting to propose refresher courses on Digital and Information Literacy, and to involve as many stakeholders as possible to make it possible to meet this need.

It is necessary to report that the main limitations of the present study are related to the scarcity of articles on the information literacy of regular basic-education teachers; we also had limitations with articles in foreign languages, except Spanish and English, and with access to other commercial databases, as they are fee-based.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci14020127/s1, Table S1: Database, author, country, keywords, category, methodology, sample, instrument/technique, important results described in each article.

Author Contributions

Each author has made substantial contributions to the conception of this work; analysis, and interpretation of data. Particularly, F.F.-O. in the conceptualization of the whole project and the funding acquisition for presenting and publishing results. G.P.-P., J.B., M.A.A.-H. and M.V.-R. in the interpretation and application of results and the review of editor’s comments; finally, J.C.-A. in the data analysis, RSL protocol and further revisions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was subsidized by CONCYTEC through the PROCIENCIA program within the framework of the contest “Applied Research Projects in Social Sciences”, according to contract [PE501078687-2022-PROCIENCIA] and “The APC was financed by the PROCIENCIA project as well as authors”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial and administrative support of Universidad Católica Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo (USAT) in Peru, Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa (UNSA) in Peru, Universidad de Sevilla (US) in Spain, Universidad de Granada (UG) in Spain y la Universidad de Huelva (UH) in Spain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- Turpo-Gebera, O.; Diaz-Zavala, R.; Cuadros-Linares, L.; Ramírez-García, A. Media and information literacy and digital culture in Peru. RISTI—Rev. Iber. Sist. Tecnol. Inf. 2022, 1, 359–370. Available online: http://www.risti.xyz/issues/ristie48.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Ortega-Villaseñor, H. Smartphones: Opportunities and risks. Perspect. Comun. 2022, 15, 111–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Barahona, A.; Molías, L.M.; Erazo, N.S.; Fassler, M.U.; Castro-Ortiz, W.; Rosas-Chávez, P. Digital competence of university teachers. An overview of the state of the art. Hum. Rev.—Int. Humanit. Rev. 2022, 11, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Arango, D.A.G.; Fernández, J.E.V.; Rojas, Ó.A.C.; Gutiérrez, C.A.E.; Villa, C.F.H.; Grisales, M.A.B. Digital competence in university teachers: Evaluation of relation between attitude, training and digital literacy in the use of ict in educational environments. RISTI—Rev. Iber. Sist. Tecnol. Inf. 2020, 538–552. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/record/display.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85084586151&origin=resultslist&sort=plf-f&src=s&sid=640dd9c9361bc3320f1375ca961a8cef&sot=b&sdt=b&s=TITLE-ABS-KEY%28%22Digital+competence+in+university+teachers%3A+Evaluation+of+relation+between+attitude%2C+training+and+digital+literacy+in+the+use+of+ict+in+educational+environments%22%29&sl=176&sessionSearchId=640dd9c9361bc3320f1375ca961a8cef&relpos=0 (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Barrios-Rubio, A.; Pedrero-Esteban, L.M. The Transformation of the Colombian Media Industry in the Smartphone Era. J. Creat. Commun. 2021, 16, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D.; Huwer, J. Computational Literacy as an Important Element of a Digitized Science Teacher Education—A Systematic Review of Curriculum Patterns in Physics Teacher Education Degrees in Germany. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.D.; Méndez, V.G.; Martín, A.M. Information literacy and digital competence in teacher training students. Profesorado 2018, 22, 253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Revuelta-Domínguez, F.I.; Guerra-Antequera, J.; González-Pérez, A.; Pedrera-Rodríguez, M.I.; González-Fernández, A. Digital Teaching Competence: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Burgos, A.; García-Sánchez, J.N.; Álvarez-Fernández, M.L.; Brito-Costa, S.M. Psychological and Educational Factors of Digital Competence Optimization Interventions Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Lockdown: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farida, F.; Aspat, Y.; Suherman, S. Assessment in Educational Context: The Case of Environmental Literacy, Digital Literacy, and its Relation to Mathematical Thinking Skill. Rev. Educ. Distancia 2023, 23, 1–26. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/red/article/download/552231/342501/2100131 (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Basantes-Andrade, A.; Casillas-Martín, S.; Cabezas-González, M.; Naranjo-Toro, M.; Guerra-Reyes, F. Standards of Teacher Digital Competence in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isín, M.D.; Sánchez, M.D.R.; Alarcón, V.; Ceballos-Saavedra, M. Impact of New Technologies on Student Competencies in Higher Education. Migr. Lett. 2023, 20, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Guerrero, A.J.; Miaja-Chippirraz, N.; Bueno-Pedrero, A.; Borrego-Otero, L. The Information and Information Literacy Area of the Digital Teaching Competence. Rev. Electrónica Educ. 2020, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cerero, J.; Montenegro-Rueda, M.; Fernández-Batanero, J.M. Impact of University Teachers’ Technological Training on Educational Inclusion and Quality of Life of Students with Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alférez-Pastor, M.; Collado-Soler, R.; Lérida-Ayala, V.; Manzano-León, A.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Trigueros, R. Training Digital Competencies in Future Primary School Teachers: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, C.; Rodríguez, F.; Oliveros, S. Electronic governance and social inclusion of the elderly through digital and information literacy strategies in Placilla, Chile. Palabra Clave (La Plata) 2022, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Martín, A.; Pinedo-González, R.; Gil-Puente, C. ICT and Media competencies of teachers. Convergence towards an integrated MIL-ICT model. Comunicar 2022, 70, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escoda, A.; Aguaded, I.; Rodríguez-Conde, M.J. Generación digital v.s. Escuela analógica. Competencias digitales en el currículum de la educación obligatoria. Digit. Educ. Rev. 2016, 30, 165–183. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/DER/article/view/317380/407477 (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- De la Calle, A.M.; Pacheco-Costa, A.; Gómez-Ruiz, M.A.; Guzmán-Simón, F. Understanding Teacher Digital Competence in the Framework of Social Sustainability: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velandia, C.A.; Mena-Guacas, A.F.; Tobón, S.; López-Meneses, E. Digital Teacher Competence Frameworks Evolution and Their Use in Ibero-America up to the Year the COVID-19 Pandemic Began: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguaded, I.; Ortiz-Sobrino, M.-A. La educación en clave audiovisual y multipantalla. RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2022, 25, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Espín, E.; Mena-Garzón, N.d.J.; Arellano_Reyes, M.; Salazar-Cueva, M.; Bravo-Bastidas, M. Aporte social y económico de la educación superior virtual en tiempos de incertidumbre. SIGMA 2022, 9, 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Inamorato, A.; Chinkes, E.; Carvalho, M.A.G.; Solórzano, C.M.V.; Marroni, L.S. The digital competence of academics in higher education: Is the glass half empty or half full? Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrando, M.d.L.; Suelves, D.M.; Gabarda, V.; Ramón-Llin, J.A. Profesorado niversitario. ¿Consumidor o productor de contenidos digitales educativos? Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2023, 26, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, M.-S.; Nuñez, P.; Cuestas, J. Competencias digitales docentes en el contexto de COVID-19. Pixel-Bit Rev. Medios Educ. 2023, 67, 155–185. [Google Scholar]

- Viñoles-Cosentino, V.; Sánchez-Caballé, A.; Esteve-Mon, F.M. Desarrollo de la Competencia Digital Docente en Contextos Universitarios. Una Revisión Sistemática. REICE Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2022, 20, 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Manabat, A.R. Bringing MIL into the margins: Introducing media and information literacy at the outskirts. Int. J. Media Inf. Lit. 2021, 6, 156–165. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/bringing-mil-into-the-margins-introducing-media-and-information-literacy-at-the-outskirts/viewer (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Cisneros-Barahona, A.; Marqués-Molías, L.; Samaniego-Erazo, N.; Mejía-Granizo, C.M. La Competencia Digital Docente. Diseño y validación de una propuesta formativa.: [Teaching Digital Competence. A training proposal desing and validation]. Pixel-Bit. Rev. Medios Educ. 2023, 68, 7–41. [Google Scholar]

- Saptono, L. The Effect of Personal Competence and Pedagogical-Didactical Competence of High School Economics Teachers in Media Literacy on Teaching Effectiveness. Int. J. Media Inf. Lit. 2022, 7, 545–553. [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo-Sánchez, S.L.; Martínez-de-Morentin, J.I.; Medrano-Samaniego, C. Una intervención para mejorar la competencia mediática e informacional. Educación XX1 2022, 25, 407–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Belmonte, J.; Pozo-Sánchez, S.; Fuentes-Cabrera, A.; Trujillo-Torres, J.-M. Analytical competences of teachers in big data in the era of digitalized learning. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Belmonte, J.L.; Sánchez, S.P.; Cano, E.V.; López, E.J. Analysis of the incidence of age in the digital competence of Spanish pre-university teachers. Rev. Fuentes 2020, 22, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Llamas-Salguero, F.; Macías, E. Formación inicial de docentes en educación básica para la generación de conocimiento con las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2018, 29, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunathilaka, C.; Wickramasinghe, R.S.; Jais, M. COVID-19 and the Adaptive Role of Educators: The Impact of Digital Literacy and Psychological Well-Being on Education—A PLS-SEM Approach. Int. J. Educ. Reform 2022, 31, 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidson, E. Pedagogía en colaboración: Competencia digital de los profesores con recursos didácticos compartidos: [Pedagogy by proxy: Teachers’ digital competence with crowd-sourced resources]. Pixel-Bit. Rev. Medios Educ. 2021, 61, 197–229. [Google Scholar]

- How, R.P.T.K.; Zulnaidi, H.; Rahim, S.S.A. The Importance of Digital Literacy in Quadratic Equations, Strategies Used, and Issues Faced by Educators. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2022, 14, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhoff, S.N.; Makubuya, T. Professional Development on Digital Literacy and Transformative Teaching in a Low-Income Country: A Case Study of Rural Kenya. Read. Res. Q. 2022, 57, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miço, H.; Cungu, J. The Need for Digital Education in the Teaching Profession: A Path Toward Using the European Digital Competence Framework in Albania. IAFOR J. Educ. 2022, 10, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Torres, J.M.; Gómez-García, G.; Ramos, M.R.; Soler-Costa, R. The development of information literacy in early childhood education teachers. A study from the perspective of the education center’s character. J. Technol. Sci. Educ. 2020, 10, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberola-Mulet, I.; Iglesias-Martínez, M.J.; Lozano-Cabezas, I. Teachers’ Beliefs about the Role of Digital Educational Resources in Educational Practice: A Qualitative Study. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloni, C.; Rangel, F.d.O.; Palma, R.S.A. Proposed Research Instrument to Investigate the Features of Digital Literacy within the Scope of Teaching Practices. Rev. Ibero-Am. Estud. Educ. 2022, 17, 1341–1356. Available online: https://www.oasisbr.ibict.br/vufind/Record/UNESP-15_8ad4456fa0ac2eeb846593075e820f76 (accessed on 3 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Cabero-Almenara, J.; Gutiérrez-Castillo, J.J.; Palacios-Rodríguez, A.; Barroso-Osuna, J. Comparative European DigCompEdu Framework (JRC) and Common Framework for Teaching Digital Competence (INTEF) through expert judgment. Educ. Tecnol. 2021, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos-Báez, A.; Pérez, Á.; Caldevilla, D. Alfabetización digital tecnológica: Formación de voluntariado: Technological digital literacy: Volunteer training. Investig. Sobre Lect. 2021, 15, 95–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellví, J.; Díez-Bedmar, M.-C.; Santisteban, A. Pre-Service Teachers’ Critical Digital Literacy Skills and Attitudes to Address Social Problems. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderschantz, N.; Hinze, A. “Computer what’s your favourite colour?” children’s information-seeking strategies in the classroom. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Sánchez, J.A.; García López, R.I.; Ramírez-Montoya, M.S.; Tánori, J. Factores que influyen en la integración del Programa de Inclusión y Alfabetización Digital en la docencia en escuelas primarias. Rev. Electrónica Investig. Educ. 2019, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarto, J.R.; Lopes, M.L. Digital literacy teachers of the 2nd and 3rd cycles of Viseu (Portugal) County schools. Rev. Bras. Educ. 2018, 23, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S.; Murray, N. An investigation of EAP teachers’ views and experiences of E-learning technology. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.; Reilly, J.; Bates, J. Teachers and information literacy: Understandings and perceptions of the concept. J. Inf. Lit. 2019, 13, 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Trindade, S.; Moreira, J.A.; Gómez, A. Evaluation of the teachers’ digital competences in primary and secondary education in Portugal with DigCompEdu CheckIn in pandemic times. Acta Sci. Technol. 2021, 43, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde-Berrocoso, J.; Fernández-Sánchez, M.R.; Revuelta, F.I.; Sosa-Díaz, M.J. The educational integration of digital technologies preCovid-19: Lessons for teacher education. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subekti, H.; Susilo, H.; Ibrohim; Suwono, H.; Martadi; Purnomo, A.R. Challenges and expectations towards information literacy skills: Voices from teachers’ training of scientific writing. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2019, 18, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanatou, M.; Prendes, M.P.; Gutierrez, I. Data-Driven Decision Making as a Model to Improve in Primary Education. J. Educ. e-Learn. Res. 2022, 10, 36–42. Available online: https://www.asianonlinejournals.com/index.php/JEELR/article/view/4337 (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Berger, P.; Wolling, J. They Need More Than Technology-Equipped Schools: Teachers’ Practice of Fostering Students’ Digital Protective Skills. Media Commun. 2019, 7, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botturi, L. Digital and media literacy in pre-service teachereducation: A case study from Switzerland. Nordic J. Digit. Lit. 2019, 14, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botturi, L.; Beretta, C. Screencasting Information Literacy. Insights in pre-service teachers’ conception of online search. J. Media Lit. Educ. 2022, 14, 94–107. Available online: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1038&context=jmle-preprints (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Cirus, L.; Simonova, I. Pupils’ Digital Literacy Reflected in Teachers’ Attitudes Towards ICT: Case Study of the Czech Republic. Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, G.M.; Silva, H.C.; de Almeida, C.C.; Lucas, M. Use of digital educational resources by educators in the early grades of elementary school. Perspect. Cienc. Inf. 2022, 27, 355–376. [Google Scholar]

- Hordatt, C.; Haynes-Brown, T. Latin American and Caribbean teachers’ transition to online teaching during the pandemic: Challenges, Changes and Lessons Learned: [La transición a la enseñanza en línea llevada a cabo por los docentes de América Latina y el Caribe durante la pandemia de COVID-19: Desafíos, cambios y lecciones aprendidas]. Pixel-Bit. Rev. Medios Educ. 2021, 61, 131–163. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, M.d.C.; Turpo, O.W.; Suárez, C. La autopercepción de competencia mediática y su relación con las variables sociodemográficas del profesorado de tres instituciones educativas ubicadas en Lima. Aula Abierta 2020, 49, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsdottir, G.B.; Hernández, H.; Colomer, J.C.; Hatlevik, O.E. Student teachers’ responsible use of ICT: Examining two samples in Spain and Norway. Comput. Educ. 2020, 152, 103877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén-Gámez, F.D.; Mayorga-Fernández, M.J.; Contreras-Rosado, J.A. Validity and reliability of an instrument to evaluate the digital competence of teachers in relation to online tutorials in the stages of early childhood education and primary education. Rev. Educ. A Distancia 2021, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen, F.D.; Mayorga-Fernández, M.J. Measuring Rural Teachers’ Digital Competence to Communicate with the Educational Community. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2022, 11, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüş, M.M.; Kukul, V. Developing a digital competence scale for teachers: Validity and reliability study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 2747–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Castillo, J.J.; Palacios-Rodríguez, A.; Martín-Párraga, L.; Serrano-Hidalgo, M. Development of Digital Teaching Competence: Pilot Experience and Validation through Expert Judgment. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibszer, A.; Tracz, M. The impact of COVID-19 on education in poland: Challenges related to distance learning. Prz. Geogr. 2021, 94, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-Mazeyra, A.; Núñez-Pacheco, R.; Barreda-Parra, A.; Guillén-Chávez, E.-P.; Turpo-Gebera, O. Digital competencies of Peruvian teachers in basic education. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 1058653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, N.; Din, R.; Othman, N. Teachers’ Perceptions and Challenges to the Use of Technology in Teaching and Learning during COVID-19 in Malaysia. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2022, 21, 281–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameras, P.; Moumoutzis, N. Towards the development of a digital competency framework for digital teaching and learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, Vienna, Austria, 21–23 April 2021; pp. 1226–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Maina, A.; Waga, R. Digital Literacy Enhancement Status in Kenya’s Competency-Based Curriculum. In Proceedings of the Sustainable ICT, Education and Learning, Zanzibar, Tanzania, 25–27 April 2019; Volume 564, pp. 206–217. [Google Scholar]

- Mañanes, J.; García-Martín, J. La competencia digital del profesorado de Educación Primaria durante la pandemia (COVID-19). Profesorado, Rev. Currículum Form. Profr. 2022, 26, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.; García, S. Use of digital tools for teaching in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Esp. Educ. Comp. 2021, 38, 151–173. [Google Scholar]

- López, C.; Cascales, A. Tutorial action and technology: Formative proposal in primary education. Rev. Electron. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2019, 22, 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Melash, V.D.; Molodychenko, V.V.; Huz, V.V.; Varenychenko, A.B.; Kirsanova, S.S. Modernization of Education Programs and Formation of Digital Competences of Future Primary School Teachers. Int. J. High. Educ. 2020, 9, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Isidro, S.; Martínez-Abad, F.; Rodríguez-Conde, M.J. Present and future of Teachers’ Information Literacy in compulsory education. Rev. Española Pedagog. 2021, 79, 477–496. Available online: https://reunir.unir.net/bitstream/handle/123456789/13467/REP%20280_ESP-EN_Nieto.pdf;jsessionid=679637404F5F3BEA8FA9C945C02719A3?sequence=1 (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Nieto-Isidro, S.; Martínez-Abad, F.; Rodríguez-Conde, M.J. Competencia Informacional en Educación Primaria: Diagnóstico y efectos de la formación en el profesorado y alumnado de Castilla y León (España). Rev. Española Doc. Científica 2021, 44, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, V.; Aceituno-Aceituno, P.; Lanza, D.; Sánchez, A. La radio escolar como recurso para el desarrollo de la competencia mediática. Estud. Sobre Mensaje Periodístico 2022, 28, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudeweetering, K.; Voogt, J. Teachers’ conceptualization and enactment of twenty-first century competences: Exploring dimensions for new curricula. Curric. J. 2018, 29, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozerbas, M.A.; Ocal, F.N. Digital Literacy Competence Perceptions of Classroom Teachers and Parents Regarding Themselves and Parents’ Own Children. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 7, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, J.; Garay, U.; Tejada, E.; Bilbao, N. Self-Perception of the Digital Competence of Educators during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Analysis of Different Educational Stages. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, S.; López, J.; Moreno, A.J.; Hinojo-Lucena, F.J. Flipped learning y competencia digital: Una conexión docente necesaria para su desarrollo en la educación actual. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2020, 23, 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Pozo, S.; López, J.; Fernández, M.; López, J.A. Correlational analysis of the incident factors in the level of digital competence of teachers. Rev. Electron. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2020, 23, 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Soifah, U.; Jana, P.; Pratolo, B.W. Unlocking digital literacy practices of EFL teachers. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1823, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walan, S.; Gericke, N. Transferring makerspace activities to the classroom: A tension between two learning cultures. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2023, 33, 1755–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Martínez-Abad, F.; García-Holgado, A. Exploring factors influencing pre-service and in-service teachers´ perception of digital competencies in the Chinese region of Anhui. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 12469–12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abanades, M. The challenges of the teacher in the university of the 21st century. Dealing with digital competence and student engagement. Rev. Int. Humanidades 2022, 13, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios-Rodríguez, A.; Guillén-Gámez, F.D.; Cabero-Almenara, J.; Gutiérrez-Castillo, J.J. Teacher Digital Competence in the stages of Compulsory Education according to DigCompEdu: The impact of demographic predictors on its development. Interact. Des. Archit. 2023, 57, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).