Why Early Career Researchers Escape the Ivory Tower: The Role of Environmental Perception in Career Choices

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Environment Perception and Postdoctoral Academic Career Choices

1.1.2. Individual Background and Postdoctoral Academic Career Choices

1.2. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Methods

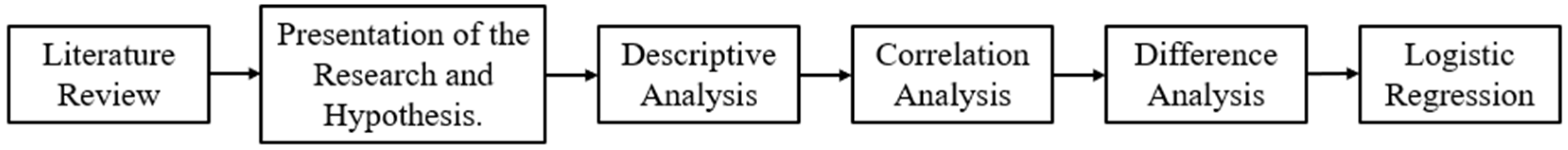

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Correlation Analysis

3.2. Differences Test Across Groups

3.3. The Predictive Effect of Environment Perception

3.3.1. Predictors of Academic Career Choice

3.3.2. Differences Between Disciplines

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Felisberti, F.M.; Sear, R. Postdoctoral Researchers in the UK: A Snapshot at Factors Affecting Their Research Output. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Drane, D.; McGee, R.; Campa, H., III; Goldberg, B.B.; Hokanson, S.C. A national professional development program fills mentoring gaps for postdoctoral researchers. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0275767. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.Q.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, J. Academia or enterprises: Gender, research outputs, and employment among PhD graduates in China. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2018, 19, 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Blackford, S. Harnessing the power of communities: Career networking strategies for bioscience PhD students and postdoctoral researchers. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365, fny033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhinnie, S. Mapping the Future: Survey of Chemistry and Physics Postdoctoral Researchers’ Experiences and Caree Intentions; Diversity Team, IOP Institute of Physics: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti, G.; Converso, D.; Di Fiore, T.; Viotti, S. Cynicism and dedication to work in post-docs: Relationships between individual job insecurity, job insecurity climate, and supervisor support. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2022, 12, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorenkamp, I.; Weiss, E.E. What makes them leave? A path model of postdocs’ intentions to leave academia. High. Educ. 2018, 75, 747–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sills, J.; Ahmed, M.A.; Behbahani, A.H.; Brückner, A.; Charpentier, C.J.; Morais, L.H.; Mallory, S.; Pool, A.-H. The precarious position of postdocs during COVID-19. Science 2020, 368, 957–958. [Google Scholar]

- Woolston, C. Postdoc survey reveals disenchantment with working life. Nature 2020, 587, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, S.; Ginther, D.K. The impact of postdoctoral training on early careers in biomedicine. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.B. Staying or going?: Australian early career researchers’ narratives of academic work, exit options and coping strategies. Aust. Univ. Rev. 2011, 53, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, M.; Tokar, D.M. The role of personality and learning experiences in social cognitive career theory. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Lopez, A.M.; Lopez, F.G.; Sheu, H.-B. Social cognitive career theory and the prediction of interests and choice goals in the computing disciplines. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, H.-B.; Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Miller, M.J.; Hennessy, K.D.; Duffy, R.D. Testing the choice model of social cognitive career theory across Holland themes: A meta-analytic path analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Q.; Ji, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.F.; Gao, W.J. Professional Identity and Career Adaptability among Chinese Engineering Students: The Mediating Role of Learning Engagement. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Xu, D. Excellent Adventurers: An Analysis of Career Choice and Path of Chinese Postdoctoral Researchers. China High. Educ. Res. 2021, 37, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Dang, Y.; Gao, W. Career Education Skills and Career Adaptability among College Students in China: The Mediating Role of Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, E.H. Environmental perception. In Environmental Geology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 214–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, E.S.; Chiu, S.Y. Does Holding a Postdoctoral Position Bring Benefits for Advancing to Academia? Res. High. Educ. 2016, 57, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, A.; Tur, E.M.; Lakens, D.; Vaesen, K.; Houkes, W. Leaving academia: PhD attrition and unhealthy research environments. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.H. Leaving academia: Why do doctoral graduates take up non-academic jobs and to what extent are they prepared? Stud. Grad. Postdr. Educ. 2021, 12, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverdlik, A.; Hall, N.C.; McAlpine, L.; Hubbard, K. The PhD Experience: A Review of the Factors Influencing Doctoral Students’ Completion, Achievement, and Well-Being. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2018, 13, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, S.; Merga, M. Communicating research in academia and beyond: Sources of self-efficacy for early career researchers. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2022, 41, 2006–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tas, Y.; Demiral Uzan, M.; Uzan, E. Self-Efficacy for Research: Development and Validation of a Comprehensive Research Self-Efficacy Scale (C-RSES). Int. J. Soc. Educ. Sci. 2023, 5, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, C.; Graversen, E.K.; Pedersen, H.S. Researcher mobility and sector career choices among doctorate holders. Res. Eval. 2015, 24, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobin, J.A.; Clifford, P.S.; Dunn, B.M.; Rich, S.; Justement, L.B. Putting PhDs to Work: Career Planning for Today’s Scientist. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2014, 13, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhang, K.; Liu, J.; Lyu, W. Credential inflation and employment of university faculty in China. Humanit. Social. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Webber, K.L. A decade beyond the doctorate: The influence of a US postdoctoral appointment on faculty career, productivity, and salary. High. Educ. 2015, 70, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krull, S.; Silva, A.A.; Afanasyeva, D.; Christensen, S.; Agostinho, M. Time for change in research careers. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e54260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, K. The future of the postdoc. Nature 2015, 520, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, L.; Emmioğlu, E. Navigating careers: Perceptions of sciences doctoral students, post-PhD researchers and pre-tenure academics. Stud. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 1770–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorenkamp, I.; Süß, S. Work-life conflict among young academics: Antecedents and gender effects. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2017, 7, 402–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, S.C.; Westerman, E.L.; Pierre, J.F.; Heckler, E.J.; Schwartz, N.B. United States National Postdoc Survey results and the interaction of gender, career choice and mentor impact. eLife 2018, 7, e40189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaffidi, A.K.; Berman, J.E. A positive postdoctoral experience is related to quality supervision and career mentoring, collaborations, networking and a nurturing research environment. High. Educ. 2011, 62, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson-Clarke, S.M.; Chaudhary, S.; Gailliard, B.M. Exploring Personal and Contextual Factors Influencing Career Choice Among Biomedical PhD Students and Post-Doctoral Fellows. Underst. Interv. 2019, 10, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine, L. Fixed-term researchers in the social sciences: Passionate investment, yet marginalizing experiences. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2010, 15, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teelken, C.; Van der Weijden, I. The employment situations and career prospects of postdoctoral researchers. Empl. Relat. 2018, 40, 396–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonja, S.; Salmon, D.G.; Quailey, S.I.; Lambert, W.M. Postdocs’ advice on pursuing a research career in academia: A qualitative analysis of free-text survey responses. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José Ribeiro, M.; Fonseca, A.; Ramos, M.M.; Costa, M.; Kilteni, K.; Møller Andersen, L.; Harber-Aschan, L.; Moscoso, J.A.; Bagchi, S. Postdoc X-ray in Europe 2017 Work conditions, productivity, institutional support and career outlooks. bioRxiv 2019, 523621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, P. How to Exploit Postdocs. BioScience 2013, 63, 245–246. [Google Scholar]

- Layton, R.L.; Brandt, P.D.; Freeman, A.M.; Harrell, J.R.; Hall, J.D.; Sinche, M. Diversity Exiting the Academy: Influential Factors for the Career Choice of Well-Represented and Underrepresented Minority Scientists. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2016, 15, ar41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, L.D. Perceived Barriers to Career Development in the Context of Social Cognitive Career Theory. J. Career Assess. 2005, 13, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.M.; Subich, L.M. The gendered nature of career related learning experiences: A social cognitive career theory perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Seals, C. Taking the next step: Supporting postdocs to develop an independent path in academia. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2019, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, M.; Sauermann, H. The declining interest in an academic career. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijstra, T.M.; O’Connor, P.; Rafnsdóttir, G.L. Explaining gender inequality in Iceland: What makes the difference? Eur. J. High. Educ. 2013, 3, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ysseldyk, R.; Greenaway, K.H.; Hassinger, E.; Zutrauen, S.; Lintz, J.; Bhatia, M.P.; Frye, M.; Starkenburg, E.; Tai, V. A Leak in the Academic Pipeline: Identity and Health Among Postdoctoral Women. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.I.; Wai, J. The bachelor’s to Ph.D. STEM pipeline no longer leaks more women than men: A 30-year analysis. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, E.D.; Botos, J.; Dohoney, K.M.; Geiman, T.M.; Kolla, S.S.; Olivera, A.; Qiu, Y.; Rayasam, G.V.; Stavreva, D.A.; Cohen-Fix, O. Falling off the academic bandwagon. EMBO Rep. 2007, 8, 977–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataille, P.; Le Feuvre, N.; Kradolfer Morales, S. Should I stay or should I go? The effects of precariousness on the gendered career aspirations of postdocs in Switzerland. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 16, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Weijden, I.; Teelken, C.; de Boer, M.; Drost, M. Career satisfaction of postdoctoral researchers in relation to their expectations for the future. High. Educ. 2016, 72, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Main, J.B. Postdoctoral research training and the attainment of faculty careers in social science and STEM fields in the United States. Stud. Grad. Postdr. Educ. 2021, 12, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, K.D.; Griffin, K.A. What Do I Want to Be with My PhD? The Roles of Personal Values and Structural Dynamics in Shaping the Career Interests of Recent Biomedical Science PhD Graduates. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2013, 12, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackford, S. A qualitative study of the relationship of personality type with career management and career choice preference in a group of bioscience postgraduate students and postdoctoral researchers. Int. J. Res. Dev. 2010, 1, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, L.E.; Ogawa, J.R.; Jones-London, M.D. Factors That Influence Career Choice among Different Populations of Neuroscience Trainees. Eneuro 2021, 8, ENEURO.0163-0121.2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, K.D.; McGready, J.; Griffin, K. Career Development among American Biomedical Postdocs. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2015, 14, ar44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Clair, R.; Hutto, T.; MacBeth, C.; Newstetter, W.; McCarty, N.A.; Melkers, J. The “new normal”: Adapting doctoral trainee career preparation for broad career paths in science. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177035. [Google Scholar]

- Roach, M.; Sauermann, H. A taste for science? PhD scientists’ academic orientation and self-selection into research careers in industry. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordling, L. How ChatGPT is transforming the postdoc experience. Nature 2023, 622, 655–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordling, L. Postdoc career optimism rebounds after COVID in global Nature survey. Nature 2023, 622, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordling, L. Falling behind: Postdocs in their thirties tire of putting life on hold. Nature 2023, 622, 881–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelló, M.; McAlpine, L.; Pyhältö, K. Spanish and UK post-PhD researchers: Writing perceptions, well-being and productivity. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 1108–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, H. Holding a post-doctoral position before becoming a faculty member: Does it bring benefits for the scholarly enterprise? High. Educ. 2009, 58, 689–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkerlind, G. Postdoctoral Researchers: Roles, Functions and Career Prospects. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2005, 24, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G.; Court, S. Psychosocial hazards in UK universities: Adopting a risk assessment approach. High. Educ. Q. 2010, 64, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, T.J. NextGen postdocs. Science 2018, 360, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Sleep Quality and Emotional Adaptation among Freshmen in Elite Chinese Universities during Prolonged COVID-19 Lockdown: The Mediating Role of Anxiety Symptoms. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2024, 26, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerad, M.; Cerny, J. Postdoctoral Patterns, Career Advancement, and Problems. Science 1999, 285, 1533–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moors, A.C.; Malley, J.E.; Stewart, A.J. My Family Matters: Gender and Perceived Support for Family Commitments and Satisfaction in Academia Among Postdocs and Faculty in STEMM and Non-STEMM Fields. Psychol. Women Q. 2014, 38, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baader, M.S.; Böhringer, D.; Korff, S.; Roman, N. Equal opportunities in the postdoctoral phase in Germany? Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 16, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-L. Ten Simple Rules for landing on the right job after your PhD or postdoc. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Academic career choice | 0.637 | 0.481 | 1 | ||||||||

| Environmental perception | (2) Institutional environment | 4.866 | 1.257 | 0.131 *** | 1 | ||||||

| (3) Organizational environment | 3.838 | 1.469 | 0.074 *** | 0.653 *** | 1 | ||||||

| (4) Living environment | 4.205 | 1.368 | 0.041 ** | 0.574 *** | 0.540 *** | 1 | |||||

| (5) Support environment | 3.725 | 1.334 | 0.094 *** | 0.573 *** | 0.541 *** | 0.518 *** | 1 | ||||

| (6) Gender | 0.483 | 0.500 | 0.053 *** | 0.016 | 0.085 *** | 0.025 | 0.033 ** | 1 | |||

| (7) Age | 2.948 | 0.641 | 0.060 *** | −0.128 *** | −0.054 *** | −0.101 *** | −0.148 *** | 0.045 *** | 1 | ||

| (8) Whether undertaking a postdoc in native country | 0.612 | 0.487 | −0.055 *** | −0.066 *** | 0.026 | 0.003 | −0.018 | 0.042 ** | −0.007 | 1 | |

| Institutional Environment | Organizational Environment | Living Environment | Support Environment | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | p | Mean | SD | p | Mean | SD | p | Mean | SD | p | ||

| Gender | Female | 4.857 | 0.029 | 0.341 | 3.733 | 0.034 | 0.000 | 4.182 | 0.031 | 0.137 | 3.691 | 0.030 | 0.044 |

| Male | 4.897 | 0.030 | 3.982 | 0.035 | 4.249 | 0.032 | 3.780 | 0.032 | |||||

| Whether in native country | In native country | 4.970 | 0.032 | 0.000 | 3.791 | 0.038 | 0.117 | 4.199 | 0.035 | 0.832 | 3.756 | 0.035 | 0.268 |

| Not in native country | 4.800 | 0.027 | 3.868 | 0.031 | 4.209 | 0.029 | 3.706 | 0.028 | |||||

| Work field | Agriculture and food | 4.868 | 1.369 | 0.241 | 4.155 | 1.538 | 0.000 | 4.382 | 1.261 | 0.000 | 3.773 | 1.382 | 0.004 |

| Astronomy and planetary | 4.825 | 1.321 | 3.627 | 1.648 | 4.077 | 1.499 | 3.765 | 1.383 | |||||

| Biomedical and clinical | 4.820 | 1.251 | 3.758 | 1.450 | 4.079 | 1.354 | 3.634 | 1.323 | |||||

| Chemistry | 4.850 | 1.318 | 3.963 | 1.495 | 4.162 | 1.523 | 3.883 | 1.410 | |||||

| Computer and mathematics | 5.076 | 1.259 | 4.038 | 1.479 | 4.462 | 1.264 | 4.000 | 1.351 | |||||

| Ecology and evolution | 4.910 | 1.189 | 3.542 | 1.273 | 4.512 | 1.281 | 3.771 | 1.289 | |||||

| Engineering | 4.955 | 1.380 | 4.099 | 1.591 | 4.196 | 1.513 | 3.897 | 1.474 | |||||

| Geology and environmental | 4.981 | 1.157 | 3.922 | 1.400 | 4.436 | 1.354 | 3.868 | 1.225 | |||||

| Health care | 4.835 | 1.310 | 4.094 | 1.523 | 4.162 | 1.370 | 3.740 | 1.354 | |||||

| Other science-related field | 4.876 | 1.241 | 3.952 | 1.541 | 4.369 | 1.323 | 3.656 | 1.320 | |||||

| Physics | 4.838 | 1.290 | 3.782 | 1.525 | 4.351 | 1.332 | 3.840 | 1.297 | |||||

| Social sciences | 5.110 | 1.038 | 3.912 | 1.367 | 4.511 | 1.345 | 3.945 | 1.245 | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional environment | 1.253 *** (0.036) | 1.290 *** (0.054) | |||

| Organizational environment | 1.115 *** (0.027) | 0.975 (0.034) | |||

| Living environment | 1.056 ** (0.028) | 0.892 *** (0.031) | |||

| Support environment | 1.180 *** (0.032) | 1.111 *** (0.039) | |||

| Gender | 1.221 *** (0.089) | 1.209 *** (0.088) | 1.235 *** (0.090) | 1.228 *** (0.090) | 1.228 *** (0.090) |

| Age | 1.251 *** (0.075) | 1.192 *** (0.071) | 1.183 *** (0.070) | 1.246 *** (0.075) | 1.272 *** (0.077) |

| Whether in native country | 0.873 * (0.066) | 0.824 ** (0.062) | 0.839 ** (0.063) | 0.843 ** (0.063) | 0.883 (0.067) |

| Intercept | 0.319 (0.125) | 0.706 (0.263) | 0.906 (0.341) | 0.533 (0.201) | 0.323 (0.129) |

| Work field | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Current address | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Number of observations | 3623 | 3623 | 3625 | 3622 | 3620 |

| R2 | 0.039 | 0.030 | 0.027 | 0.034 | 0.043 |

| Engineering | Science | Humanities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional environment | 1.335 *** (0.068) | 1.363 *** (0.141) | 0.706 (0.217) |

| Organizational environment | 0.987 (0.043) | 0.877 (0.078) | 1.025 (0.212) |

| Living environment | 0.883 *** (0.038) | 0.852 * (0.071) | 1.185 (0.218) |

| Support environment | 1.099 ** (0.047) | 1.196 ** (0.108) | 1.266 (0.279) |

| Gender | 1.189 * (0.107) | 1.104 (0.203) | 1.931 (0.899) |

| Age | 1.329 *** (0.106) | 1.245 (0.184) | 1.229 (0.421) |

| Whether in native country | 0.825 ** (0.079) | 1.000 (0.191) | 1.489 (0.649) |

| Intercept | 0.285 (0.134) | 1.579 (1.973) | 1.340 (2.248) |

| Current address | yes | yes | yes |

| Number of observations | 2229 | 631 | 152 |

| R2 | 0.033 | 0.042 | 0.054 |

| Hypotheses | Acceptance | Rejection |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 | Yes | |

| Hypothesis 2 | Yes | |

| Hypothesis 3 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Why Early Career Researchers Escape the Ivory Tower: The Role of Environmental Perception in Career Choices. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121333

Liu X, Zhang X, Li Y. Why Early Career Researchers Escape the Ivory Tower: The Role of Environmental Perception in Career Choices. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121333

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xinqiao, Xinyuan Zhang, and Yan Li. 2024. "Why Early Career Researchers Escape the Ivory Tower: The Role of Environmental Perception in Career Choices" Education Sciences 14, no. 12: 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121333

APA StyleLiu, X., Zhang, X., & Li, Y. (2024). Why Early Career Researchers Escape the Ivory Tower: The Role of Environmental Perception in Career Choices. Education Sciences, 14(12), 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121333