Abstract

The past two years saw a rapid proliferation of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in higher education. Digital technologies and environments offer many affordances. New digital literacy practices in universities have implications for teaching and learning. E-textbooks, in particular, act as mediating tools that can facilitate teaching and learning through developing students’ understandings of scientific concepts. This paper positions e-textbooks as mediators of learning, rather than merely objects of learning. There is thus a need to understand the mediating role of e-textbooks that lecturers draw on in their teaching. While much research was conducted on students’ use of e-textbooks, relatively little was conducted on lecturers’ use of e-textbooks in engineering education. The current study aimed to answer the following research question: What are lecturers’ perspectives on the use of e-textbooks to facilitate learning in engineering? To address this question, data were collected through five individual interviews conducted with engineering lecturers working in the Extended Curriculum Programme (ECP) of first-year students from three engineering departments (chemical engineering, mechanical engineering, and nautical science) at a university of technology in South Africa. The data were analysed using thematic content analysis with the help of ATLAS.ti. Data analysis was guided by a theoretical framework that drew on the cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT). In this study, the focus was on e-textbooks as pedagogical tools within engineering teaching and learning. The findings provide insight into how lecturers incorporate e-textbooks into their teaching, but also reveal the extent to which new digital literacy reading practices remain unfamiliar to engineering lecturers. CHAT enabled the identification of a critical insight, namely, the tension between mediation and division of labour. This highlights important aspects of the discourse surrounding seamless technology integration in higher education. The discussion points to the need for an expansive transformation regarding the use of e-textbooks as important mediating tools for teaching and learning.

1. Introduction

In South Africa, traditional and comprehensive universities in higher education were able to adjust relatively swiftly to these new demands. However, universities of technology (UoTs) faced substantial challenges, which underscored existing inequalities in access to and participation in higher education [1]. In response to the pandemic, South African Higher Education Minister, Blade Nzimande, announced in March 2020 that all universities would move to remote online or distance learning to save the academic year [2]. Following this directive, the executive management of universities across the country advised educators to prepare for fully remote learning, utilising various modes of knowledge transfer, including video, audio, and interactive reading texts.

Engineering lecturers at South African higher education institutions (HEIs) encountered significant challenges during this transition, particularly in adapting their course content to online formats and in devising strategies to accommodate a diverse student body. South Africa’s higher education landscape comprises three distinct types of universities: traditional universities, comprehensive universities, and UoTs. The UoTs, which evolved from institutions akin to technical colleges and were formerly known as technikons, do not typically enjoy the same research-intensive status as their traditional counterparts. These institutions were originally established to provide vocational education and often hired faculty with technical expertise from professional sectors rather than those with advanced, research-oriented degrees [3].

The majority of students at UoTs come from marginalised communities and previously disadvantaged backgrounds, with limited resources. During the pandemic, particularly in November 2020, these students had to rely heavily on digital resources, such as e-textbooks, for all their engineering subjects. With no access to university libraries and the acquisition of physical textbooks from global online platforms, such as Amazon, being time-consuming, the shift from paper textbooks to digital e-textbooks became inevitable.

Furthermore, the transition to technology-enhanced learning in South Africa posed unique challenges, especially for first-year engineering students, many of whom come from rural areas with limited access to technology. A significant portion of these students encountered computers for the first time upon entering tertiary education. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of online learning across all South African universities, revealing the advantages of digital resources, such as e-textbooks, particularly in terms of affordability and accessibility. However, the transition was not seamless for all educators. Lecturers accustomed to face-to-face teaching often struggled with the digital shift, facing the daunting task of converting traditional lectures into online formats. Conversely, those with prior experience in technology-integrated teaching recognised the potential of online platforms to enhance educational opportunities. This study investigated lecturers’ practices regarding the use of e-textbooks to understand whether and how these digital resources transformed teaching practices.

2. Literature Review

E-textbooks were adopted by universities as digital equivalents of physical books, offering additional interactive functionalities that enhance the learning experience [4]. Unlike traditional digital reading, e-textbooks promote adaptive and self-regulated learning for students [5,6]. This section explores the various aspects of e-textbook use and interactivity.

Despite extensive literature, there is no universally accepted definition of an e-textbook, with definitions varying depending on context and usage. Some explanations liken e-books to “paper behind the screen” [7,8,9,10], which does not differentiate them from other digital formats, such as PDFs [10,11,12]. E-books are generally defined as digital texts accessed via electronic devices such as e-readers, personal digital assistants (PDAs), or mobile phones [3,13].

Understanding the distinction between e-textbooks, e-books, and PDFs is crucial. The literature offers various names for academic reading, but e-textbooks stand out due to their degree of interactivity, which significantly influences how students interact with the text [14,15,16]. Definitions of e-textbooks often include the integration of workbooks, reference books, exercise books, casebooks, and instruction manuals [6]. Many publishers now offer interactive e-textbooks designed to meet curricular standards, featuring static hypertext or multimodal text connected to the internet and hosted on educational platforms [6].

Interactive e-textbooks have the potential to enhance learning outcomes through the tools they provide [14]. These e-textbooks can be classified as either “page-fidelity e-textbooks”, which replicate the static layout of physical books, or “reflowable e-textbooks”, which include multimedia and self-testing features [17]. These interactive functions can significantly impact student engagement, though the cost of engineering e-textbooks, ranging between R800 and R1500, can be a barrier depending on the publisher and the interactive platform used.

While interactive e-textbooks offer more features to engage students, their adoption is not guaranteed [18]. Studies indicate mixed student preferences between e-textbooks and physical textbooks [19]. Some students prefer e-textbooks [20,21], while others favour physical textbooks [22], often due to factors such as cost and familiarity. Although traditional textbooks are generally more expensive, the perceived usefulness and satisfaction of learning with e-textbooks play a crucial role in their continued adoption [23,24,25,26,27,28].

Martin-Beltrán, Tigert, Peercy and Silverman [29] found that students were more likely to re-read and use text features for comprehension with digital texts, suggesting that traditional texts might better support literacy development. Martin-Beltrán et al.’s [29] findings highlight the importance of well-designed text features in both digital and traditional formats and the need for educators to guide students in using these features effectively.

However, introducing a new tool, such as interactive e-textbooks, does not guarantee a smooth transition from face-to-face to online learning, especially for students unfamiliar with digital learning environments [14,23,30]. While these e-textbooks offer various tools to support student learning, their success depends on factors such as student engagement and interest in the subject matter [31].

The e-textbooks, whether digital or physical, provide a structured framework that helps learners follow a systematic syllabus and progress through their courses. They reduce the time and effort required by teachers to prepare course materials, while also enabling students to study at their own pace, thereby fostering autonomy and independence [11,32,33]. The integration of e-textbooks into higher education offers significant potential, but their effectiveness depends on thoughtful implementation and the willingness of both educators and students to adapt to new learning tools [34].

3. Theoretical Framework

This study used cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT), originally proposed by the Russian socio-cognitive theorists, Vygotsky [35] and Leont’ev [36], and further developed by Engeström [37,38], as a guiding framework. CHAT alerts us to the relationship between subjects and the objects of their activities, the role of tools, mediation, and the context of the activity [37]. Specifically, CHAT understands that human activity is always undertaken by subjects, mediated by cultural tools, and embedded within a social context. These interactions are known as the “activity system” [37]. One way to understand the full “activity system” of transformation of the activity system is via the ZPD.

Vygotsky’s [37] concept of the ZPD was introduced as a critique of psychometric-based testing in Russian schools, which only assessed learners’ current level of achievement, neglecting their potential for future development. The ZPD highlights the potential for emerging behaviour and the “future of development” [37,38]. In this particular study, the focus was on e-textbooks as tools in an engineering teaching and learning system. In the sections that follow, more detail on the theoretical framework used to guide the study, and the theoretical and methodological advantages that CHAT brought to the study, will be discussed.

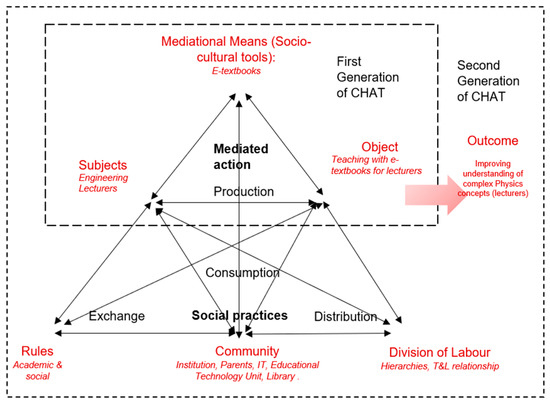

The first principle of the activity in CHAT is that the object drives the activity [38]. “CHAT views activity in an activity system as the collective, object-orientated, tool-mediated actions of a group as influenced by culture, history, and economics’’ [39]. CHAT distinguishes between the object and the outcome of a system (see Figure 1). The object is what the subjects understand as the purpose or intention of the activity; it “propels them forward to take action” [40]. In a teaching and learning activity system, we should, firstly, identify the object. In this study, the object was promoting the acquisition of engineering knowledge, more specifically, that which is contained in engineering e-textbooks.

Figure 1.

Second generation CHAT: a teaching and learning activity system [37].

Secondly, we should identify people who are participating in the system. In this case, it can be any educational activity system in which the subjects are engineering lecturers whose purpose (or object) is to teach [41] (see Figure 1). More specifically, the other subjects are students who are in a process of understanding the engineering knowledge that is contained within e-textbooks. The subject acts on an object in order to transform it, using a socio-cultural tool to reach the desired outcome in the activity system.

The focus of this study was e-textbooks that are understood as socio-cultural tools in support of the object of knowledge acquisition. Within this system, there are other socio-material and cultural mediational tools, such as curricula, facilities, equipment, internet-based and library-based resources and a learning management system (LMS), among others, that are also directed at the object. In order to work successfully on this object, human and other resources are needed—and these may or may not be sufficient for the attainment of the object [42]. This is because university teachers and students work as part of a much broader system that is embedded in an institutional culture that has rules and hierarchies of decision making (or rules and divisions of labour, respectively).

The outcome is the result of the focus on the object. In CHAT, it is important not to conflate the object and the outcome, as an effective activity system must be driven by the object and not the outcome [43]. Thus, the outcome flows from the activity as a whole. In this study, the outcome was promoting students’ academic success in engineering. According to CHAT, the outcomes can only be attained if the participants do not lose sight of the object. These objects or tools in an activity system can be human, physical, cultural, or conceptual.

CHAT also points to the socio-cultural-economic context in which the activity occurs. Activity systems are bound by rules. The rules and divisions of labour may enhance or inhibit the students’ and teachers’ ability to work towards the acquisition of engineering knowledge. The tools and resources need to be available, and appropriate rules and divisions of labour should guide the system (e.g., which tasks are appropriate for students, and which are more appropriate for teachers in achieving the object). In addition, all activity systems include a division of labour, that is, different subjects and human mediators, in their focus on the object, will play different roles and may have different levels of status in a social hierarchy.

The community of an activity system comprises those who are affected by the systems (e.g., parents, professional bodies, employers, etc.), but who are not directly involved in the work of achieving the object [44]. For example, there is a community beyond the subjects that are affected by the activity system that offers support to it, or benefits from the activity. The community can be beneficiaries of the activity, but also stakeholders in the activity. In the case of this study, important community participants included the institution’s IT department that maintains the LMS and internet connectivity and educational technologists who play a role in staff training in the use of e-textbooks. While the current study had a particular focus, namely, the e-textbooks that are used to achieve the object of learning, the whole activity system, both processes and outcomes, have to be studied [37].

CHAT includes a focus on the historical development of the activity system. South Africa is an economically, culturally, and socially stratified country inhabited by diverse population groups. The country’s unique political history created distinct socio-cultural margins. CHAT provides an especially powerful research lens in the South African context, as it takes the historical, cultural, and socio-economic context of the country into consideration when studying engineering education. Practices and conventions in education have “deep roots” [45] and are slow to change to accommodate new objects, subjects, tools, rules, communities, and divisions of labour [46]. CHAT thus warns that the introduction of a new tool, such as an e-textbook, could cause disruptions in the system. Such disruptions are not necessarily negative, as activity systems are not static. In other words, they are consistently changing the ways they operate, the resources and tools they use, and orientating themselves towards different purposes.

CHAT is particularly interested in researching new tools in an educational system, as it focuses on development and change in activity systems, often arising from historically derived tensions in an inefficient system [47]. Indeed, many educational studies in CHAT focus on the introduction of new technologies into teaching and learning systems (see e.g., Hardman [30]). One of the difficulties of introducing new tools into the system is that they can change the object, in fact, they may even become the object. This is known as a “tool object reversal” [48]. In their study, Schuh et al. [14] (p. 306) point out that “e-textbook use can be limited when students act on it merely as an object without any intentional goal”. In other words, if the technology is too disruptive or too complex, it becomes the focus of the activity instead of the tool and therefore will not achieve the intended object. By studying the whole system, researchers can identify the interactions that subjects have to negotiate, as well as the tensions and contradictions that are foregrounded when a new tool is introduced.

CHAT is a dialectic theory, and the dialectic concept of “contradiction” plays a crucial part in it. Contradictions make the object a “moving, motivated and future-generating target” [49] (p. 89). Finding contradictions or “sticking points” in an activity system points to ways of improving practices within the system. In an activity system analysis (ASA), these misalignments, contradictions, and other disturbances “hold within them the possibility of the collective propelling themselves forward to search for new ways of doing and achieving ‘what is not yet there’” [39] (p. 14).

Finally, CHAT provides a method for researchers to understand and describe the interactions between individuals and the environment in a natural setting [49]. Individual interaction is based on holistic engagement between individuals and their environment. CHAT is an effective unit of analysis in an investigation of how students and lecturers use a new tool, such as e-textbooks, in a learning environment. The purpose of this study was to understand the digital literacy practices of students in order to improve teaching practice. This study used students to identify and understand students’ digital literacy practices and determine how these enhance student learning.

4. Method

4.1. Case Study Research Design

A case study is a research design that aims to derive meaning from a specific phenomenon, where related variables cannot be separated from the context [50,51]. The primary objective of a case study is to gain an understanding of a single case rather than comparing multiple cases to draw general conclusions [40]. This research found its methodological foundation in the work of Yamagata-Lynch [40] (pp. 78–79), who argues for the commensurability and established efficacy of case study methodology within the realm of CHAT. Yamagata-Lynch’s insights illuminate how case study approaches, with their intrinsic focus on the complexity and contextual richness of specific instances, are uniquely suited to unpacking the nuanced dynamics inherent in CHAT.

Each case study presents a unique narrative, and the expected outcome is to provide specific insights and findings rather than making generalisations [52]. However, in the past, there were divergent opinions regarding the validity and significance of the information obtained from a case study. Today, the role of the case study procedure in engineering education is generally acknowledged. Cohen, Manion, and Morrison [53] believe that the results of case studies could very well be transferable to other phenomena. Case studies are regarded as valuable supplements to other research techniques.

This study employed a case study as a research method because it is well suited to addressing descriptive questions such as “how” and “why” in an empirical investigation that explores a current phenomenon within its real-life setting [51,54]. This study focused on a single case with embedded units, which involved examining multiple units or objects of analysis within that single case.

4.2. Sample for This Study

Purposive sampling entails deliberately selecting specific participants or settings based on their potential to provide crucial information that may not be as readily accessible through other methods [50]. For this study, the author selected students and lecturers from the ECP, as these programmes already implemented the use of e-textbooks in the physics subject.

4.3. Data Analysis

During the study, the author took on the role of participant observer by sitting at the back of the computer lab classroom, taking notes on an observation sheet, and managing the audio recorder. The audio recordings were transcribed. The transcriptions consisted of 12 interviews with participants after the reading task which was introduced and used on an e-textbook containing physics for engineers and science students. The excerpts used in this article were analysed using ATLAS.ti software.

Data analysis was conducted using thematic analysis. This inductively and deductively identified themes as they emerged from the interviews in a cyclical process of analysing, coding, validating, and creating themes, which are expressed in different facets of pedagogical practices. The resulting themes were correlated with the literature. The software ATLAS.ti desktop was used for the coding process and the development of themes.

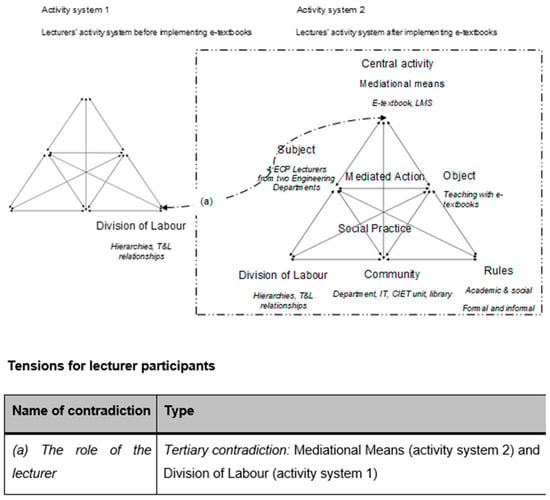

The method of analysis was based on the framework for identifying and analysing contradictions presented by Engeström and Sannino [55]. The analysis was conducted in four steps, which resulted in the identification of four types of contradictions, presented in the discussion section. In the first step, data were reduced by identifying segments significant to the research questions (cf., Jordan and Henderson [56]). These were segments in which the respondents mentioned challenges that teacher leaders discussed in coaching sessions. The second step was analysing each significant segment separately, trying to categorise the section according to the four types of manifestations [55]. Figure 2 shows an example of how the analysis of manifestations was conducted; each significant segment was noted, summarised based on the author’s understanding of the quote and its context, and compared to the descriptions of manifestations in order to categorise the section as dilemma, conflict, critical conflict, or double bind. Arguments for the categorisation of manifestation were also noted, and key words for each manifestation were italicised. This resulted in manifestations of contradiction (see Figure 2). In the discussion section, examples are given of the manifestations, aiming to increase the transparency of the results.

Figure 2.

A teaching activity system (Source: Engeström [37]).

4.4. Ethics

The ethical application for this research was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Research Committee (ERC) of the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment (FEBE) at the University of Cape Town (UCT). Key ethical considerations included obtaining informed consent, ensuring confidentiality, and protecting participants from any potential harm or discomfort.

Informed consent was paramount, with participants fully briefed on the study’s aims, their role in it, and their right to withdraw at any point without any repercussions. Privacy and confidentiality were also carefully managed, particularly in classroom settings where group activities may limit individual privacy. To address these concerns, participants’ contributions were anonymised and all data were securely stored with access restricted to the research team, ensuring the protection of participants’ identities and the integrity of the research process.

5. Discussion

5.1. Data Analysis

Research on the effects of e-learning on the roles of lecturers in digital spaces remains limited [57]. While some studies focus on understanding and accommodating individual responses to change, there is a lack of emphasis on the practical challenges and lived experiences of academics during the transition to digital pedagogy. In contrast to the increasing body of research exploring the student experience in e-learning, where student perspectives are prioritised [58], the voices of lecturers are often overlooked.

As can be seen in Table 1, Lecturers 1, 2, and 3 fulfil multiple roles in their departments. These include not only teaching and research, but also administrative support for the extended curriculum programme in their department. The participants hold the following positions: one is a junior lecturer, one a lecturer, and two are senior lecturers. Before being appointed as lecturers, all participants started their careers at the current university.

Table 1.

Lecturer-participant characteristics.

Within the CHAT framework, the roles of lecturers are understood through the concept of the division of labour, where different members of the academic community engage in various roles with distinct purposes and objectives (mediated action). The division of labour involves the negotiation of responsibilities, tasks, and power dynamics within a classroom setting, whether it be face to face or online, and extends throughout the university structure. In this article, division of labour refers to the manifestation of participants’ roles in their teaching. Leont’ev’s emphasis on the division of labour underscores its influence on our thought processes as he argues that object-oriented activity is mediated by tools and occurs in specific conditions [47].

As part of the interview, the lecturers discussed their visions and ideas about their own teaching. All the lecturers interviewed claimed to incorporate a significant amount of interactivity into their classrooms. Lecturers 2 and 3 mentioned interactive teaching styles as an example:

“I tried to promote an open atmosphere, I want students to interact. So, I tried to keep things a little bit light. … my teaching style is interactive by supporting students with understanding concepts. For example, if a student asks a question that you would consider ridiculous, to some extent, I try not to just say ‘yes, it’s wrong, or yes, it’s right’. I tried to dig a little bit deeper, even if a question was completely wrong, and maybe the whole class could see it. However, I try to dig deeper into where the misconception might have led the students to that conclusion for that type of question just to try and make it seem like it’s open for conversation. It’s free. They can ask whatever comes to their mind. They can ask, and without feeling too much of a judgement.”[Lecturer 2]

Lecturer 3 also described their teaching style as:

“interactive. And I am not somebody that wants to stand in the front of the class and speak the whole time, and when I’m done, I leave.”

However, each lecturer seemed to draw on different philosophies underpinning interaction. For example, Lecturer 4 commented on the idea of facilitation:

“The lecturer’s role is to facilitate the learning to guide and help a student gain some skills based on specific subjects. Students are coming to the classroom to acquire knowledge and skills for their future fields.”

Lecturer 1 drew on the conversational framework proposed by Laurillard [59] and clickers to improve the participation of the students:

“When I started asking myself the question, ‘how can my students be active participants in the conversation or dialogue that is happening between the students and me?… I adopted the clickers to improve the dialogue in the classroom. So, on the conversational framework, Laurillard also talked about another second phase of it, which is called the interactive side. When you bring in a system, the interactive side becomes more apparent … make sure that what you’ve taught in the classroom now is the reinforcement to test the student’s understanding or to gain that level of understanding.”

Lecturer 2 conflated the interactivity with the use of humour:

“I try to insert jokes here and there and try to lighten up the mood so that, because I feel like they are learning, it makes it easy for the students to ask and request for clarity on something they don’t understand if they feel like the classroom is a safer space. … my teaching style of physics as it’s kind of an involved subject. So you … and there’s a lot of content, so you do that, but you can’t do that all the time.”

Nonetheless, all four engineering lecturers agreed that lecturing should be interactive and dialogical. Interactive communication between lecturers and students is part of their pedagogical practice. According to Smagorinsky [60] (p. 69), teaching involves mediation, primarily through scaffolding, guidance, and assessment. The terms “scaffolding” and “providing guidance” refer to the use of mediation techniques that involve students in problem-solving activities using cultural tools. In this perspective on teaching, a teacher, who expects students to use tools that are unfamiliar to them for tasks that do not build upon their previous problem-solving experiences, is not truly teaching, but merely assigning and testing. This does not imply that teachers should only ask students to do what they already know, as that would negate the purpose of education. However, it does emphasise the importance of aligning formal instruction with students’ prior culturally fostered tool use. When there is little or no congruence between instruction and students’ existing knowledge, and when teachers do not establish a reciprocal relationship with students to support appropriate tool use, the instructional process is likely to be ineffective.

The main idea of teaching practice is that to be a successful teacher, a conversation between the lecturer and the students is laid out in a dialogical manner. Vygotsky’s concept of the zone of proximal development (ZPD) implies that students need assistance from more capable (or more knowledgeable) others. Such mediation occurs through social interaction. Vygotsky explains the ZPD [61,62] (p. 113) as follows:

“The zone of proximal development defines those functions that have not yet matured but are in the process of maturation, functions that will mature tomorrow but are currently in an embryonic state. These functions could be termed the ‘buds’ or ‘flowers’ of development rather than the ‘fruits’ of development. The actual developmental level characterises mental development retrospectively, while the zone of proximal development characterises mental development prospectively.”

The ZPD is therefore based on the fact that the more knowledgeable one assists the less knowledgeable one. This can be achieved by other students, for example, when working in groups, as Lecturer 3 mentioned:

“So, you kind of teach them that you don’t only have to think one way … you can think outside the box as well. I like group work. So, I’ll explain something on the board. And then I’ll give them a question. And they can work in groups. I don’t mind if they’re working in groups because sometimes it’s easier when a student explains to another student what they are doing wrong or what they do not understand because they sometimes speak the same language versus me, not the same language thing.”

Many scholars, such as Smagorinsky [60,62] and Hardman [63], agree on the crucial role lectures play in assisting students and mediating in online spaces, even though scholars are still trying to understand how much assistance should be provided to students to make them independent learners and promote self-regulated learning. Sociocultural constructivist views of teaching and learning emphasise the significant agency and active role of learners-as-teachers in the educational process. In constructivist approaches, teachers follow the ZPD concept to move students from an unknown area of knowledge and concepts by using teacher mediation as part of scaffolding tasks.

In comparison with the other lecturers discussed above, Lecturers 2 and 4 described their teaching philosophy as interactive by making the lecturing space informal and “less serious”. Setting up rules (whether formal or informal) in the classroom allows these lecturers to promote space for learning by making mistakes. The effect of making informal classroom rules is to promote a student-centred approach, as mentioned by Lecturer 2:

“So, I mean, the lecturer can be serious all the time. So, students know that they need to be able to focus on something, when they need to do something, but they can also relax a little bit when time allows.”

Students develop an understanding of engineering concepts in different ways, as Lecturer 2 explained:

“Students have different ways of learning; some people are visual people, some are kinesthetics and some are whatever. So, some people learn best with experience, some people learn best by thinking, and some people learn best by just looking. So, for people who are visual, they just want to see the words and whatever.

Lecturer 2 further related how e-textbooks allow students to learn in these different ways:

“E-textbook is the best because the student can actually have all these ways of learning. Depending on the software you have, you can actually have someone reach out the thing for you, which is wonderful. With [a] paper textbook, you really can’t have all these options of learning.”

As demonstrated, all the lecturers mentioned that their teaching style is interactive, and they all expressed their views on teaching with e-textbooks. This links the teaching approach directly to the adoption of e-textbooks. At the beginning of the interviews, the lecturers did not have a clear understanding of the differences between an e-textbook and a paper book; however, by the end of the interviews, the lecturers showed greater appreciation for the affordances of e-textbooks. More specific discussion of the lecturers’ practices around the use of e-textbooks is provided below.

5.2. Contradiction Analysis of Lecturers’ Practices

The interviews conducted with four lecturers that presented contradictions are shown in Figure 2.

A tertiary contradiction is symbolised by (a) in Figure 2 in the lecturers’ activity, which arises from a tension between mediational means and division of labour. This contradiction underscores the transformative impact of the e-textbook on the conventional role of the lecturer. With the advent of the e-textbook, lecturers are no longer just content presenters (if, indeed, they ever were). They now face the challenge and opportunity to design and curate enriched learning experiences. For example, Lecturer 2, capturing this sentiment of reliance on the e-text for grasp of the content, noted:

“E-textbook makes life so much easier in terms of understanding the content yourself, then being able to deliver the content, and then being able to pursue assessment. It’s brilliant.”

This statement suggests that, while e-textbooks aid lecturers in grasping content, effective teaching extends beyond mere understanding. Although e-textbooks can bolster lecturers’ comprehension, they still bear the responsibility of conveying content to students in a comprehensive manner, intertwining it with context, insights, and structure. This also raises concerns about diminishing lecturer–student interactions and potential loss of instructional control.

While the e-textbook offers a wealth of resources, the responsibility falls on the lecturer to harness it effectively, ensuring a holistic learning journey. This contradiction captures the evolution from a traditional teaching model to a more culturally advanced, student-centric approach facilitated by the e-textbook. Lecturer 3 further emphasised the need for balance:

“I think e-textbooks can definitely assist you in your teaching … It’s there to support your teaching, not take over. Those lecturers who just use the e-textbook to teach on their behalf need to be cautious.”[Lecturer 3]

This presents a risk: while e-textbooks offer undeniable advantages, relying solely on them could erode the lecturers’ active involvement in teaching. Lecturer 3’s comment illustrates the importance of maintaining agency and control over the instructional process. This contradiction arises from a clash between the capabilities of e-textbooks, as intermediaries, and the conventional beliefs and roles of lecturers. On the one hand, e-textbooks offer tools and resources that can simplify the teaching process, as articulated by Lecturer 2. On the other hand, there is a realisation, particularly from Lecturer 3, that relying solely on e-textbooks can diminish the active role of a lecturer. The disparity between the capabilities and potential of the e-textbook and the lecturers’ actual utilisation of them creates this conflict. Effective teaching goes beyond content comprehension. It is a blend of pedagogical strategies, instructional design, student engagement, and clear communication. A pronounced conflict surfaces when lecturers use e-textbooks primarily for assessment, despite acknowledging their benefits for scaffolded learning. This discord between stated belief and action accentuates the contradiction.

Moreover, Lecturer 1 adds another dimension by highlighting that “using [name of an e-textbook platform] solely for assessment overlooks its potential for enhancing student learning”. This indicates that e-textbooks are not just assessment repositories; they should act as dynamic platforms aiding student performance, monitoring and facilitating various levels of lecturer–student engagement. This contradiction emerges from a double bind because, if lecturers use e-textbooks only for assessments, they miss their pedagogical benefits. However, if they lean too heavily on e-textbooks, they risk diminishing their active role and possibly the quality of student–lecturer interaction. This puts lecturers in a position where they seem trapped between two conflicting demands or constraints.

Additionally, this contradiction speaks to how the role of the lecturer is traditionally conceived, and how the e-textbook has the potential to shift this role. Historically, the role of lecturer is understood in various ways, from “sage-on-the-stage” to learning facilitator. However, as scholars, such as Ahn [5], Gu et al. [7] and others argued, e-textbooks can foster self-regulated learning (Self-regulated learning refers to the process where learners personally initiate and manage their own learning processes. It is not just about the ability of students to study independently, but rather their ability to understand and control their own learning). The objective is not to replace lecturers with e-textbooks, but to leverage them as supplementary tools to demystify intricate engineering concepts. For instance, Lecturer 2’s initial response to the question of whether the e-textbook could replace the lecturer was initially affirmative: “Obviously, I’m a teacher, I never want to agree with it that something can replace me, but the real answer is ‘yes’.” Further discussion with Lecturer 2 elaborated and clarified their response:

“It is also child [student] dependent because there are some students who will never be able to function in a classroom but, if you give them a laptop, you give them access to everything. And they still want to be in the classroom being taught something. Yes. So, I wouldn’t say replaced, because I feel like some things can be supplemented.”

The lecturer later added a nuance, suggesting that the situation is student-dependent, with some learners thriving in a digital environment. Here, the emphasis is not on replacing lecturers, but supplementing their teachings. This mirrors a broader trend: students leveraging e-textbooks to foster independent learning.

Lecturer 4 identified the role of the e-textbook as a facilitator and his role as follows:

“… lecturer comes in with more effort, especially to cover the background [engineering problem] for the students on what they’ve been exposed to help them use their imagination. So, e-textbook is linked to content and doesn’t really stretch the minds of the students to a point where, if you want to make an example about a particular concept, you want to make an example and you want to bring a typical application of that particular concept. So, an e-textbook won’t do that for you. It was just purely to explain what is in the book.”

E-textbooks, while content-rich and enhanced with visualisations and simulations, underscore the lecturer’s role in providing contextual understanding and relevant application examples. A notable observation shared by multiple lecturers is the evolving nature of their role. With the advent of e-textbooks and supplementary resources provided by publishers, the primary responsibility of lecturers in content presentation seems to be supported, if not partially replaced. This evolution triggers two prominent concerns: firstly, the potential diminishment of the lecturer’s unique role, and secondly, the prospective enhancement in teaching quality when e-textbooks are optimally utilised. From a CHAT perspective, it is crucial to consider the cultural and historical aspects of teaching. Certain lecturers perceive e-textbooks as a constraint, feeling a reduction in their agency and autonomy. This sentiment might stem from the sense of control they possess in traditional teaching contexts. Conversely, some lecturers view the incorporation of e-textbooks as a progressive step, leveraging technology to complement and enrich their instruction [64].

For example, Lecturer 3 elaborated her view regarding e-textbooks and teaching:

“Just because there’s an e-textbook doesn’t mean you can stop teaching, lecturing, and explaining what is happening within that topic. Otherwise, there is a disconnect between the students, the lecturer, and the e-textbook. So, you have to make sure that everybody’s working together, and the e-textbook contributes to your teaching, but it doesn’t take over your teaching.”[Lecturer 3]

Furthermore, Lecturer 2 shed light on a nuanced challenge: students perceiving lecturers’ e-textbook usage as a substitute for active teaching. This speaks to a broader discontent for some students between student expectations, rooted in traditional methodologies, and contemporary teaching objectives.

“I found that even with my final year students, when you get to chapters that maybe have a lot of theory … And when you direct them to a resource, even if it’s a video or something else, the perception that they feel like you’re not teaching, you’re trying to get away with teaching and you’re being lazy, or it’s not what they pay for, or those types of vibes, or reactions, or things like that. So I think that might be a disadvantage.”[Lecturer 2]

In the given instance, Lecturer 2 expressed frustration with her experiences. Historically, students were frequently directed on tasks without adequate guidance on effectively managing their individual study and learning routines. The pedagogical approaches adopted became particularly relevant during the challenges posed by COVID-19.

Teaching and learning under social distancing conditions of the global pandemic, from 2020 onwards, brought the case for the use of technology for remote education into focus. The shift to remote teaching and learning made interest in e-textbooks more integral than ever. However, Lecturer 3 captured the essence of the prevailing sentiment:

“You are kind of influenced by what is happening around you, for example, the fact that e-textbooks are becoming so popular and common. The pandemic, where we couldn’t teach face to face. So, it definitely changes the way you teach and your teaching philosophy because it makes you think about how to make your teaching methods better.”

Lecturer 3 acknowledged the influence of external factors, such as the popularity and ubiquity of e-textbooks, as well as the shift to remote teaching during the pandemic. These factors prompted the lecturer to reconsider their teaching methods and philosophy by seeking ways to improve their instructional approaches. In this extract, Lecturer 3 also agreed that e-textbooks changed their teaching philosophy, but did not explain how and what functions e-textbooks fulfilled, or how they helped this lecturer.

6. Limitations

The limitations of this study include its focus on a single case study of a University of Technology in South Africa, which could limit the generalisability of the findings to other institutions or contexts. While e-textbooks have the potential to enhance access to learning materials, not all students have reliable access to the necessary devices, internet connectivity, or digital infrastructure. In the South African context, disparities in access to these digital tools could present a significant barrier to the effective use of e-textbooks.

Furthermore, the success of e-textbooks may be constrained by the availability of adequate technical support for both students and lecturers. Without sufficient training on how to effectively use these digital resources, their integration into the teaching and learning process may be compromised, reducing their overall impact.

7. Conclusions

CHAT offers a unique and comprehensive lens through which to analyse the integration of e-textbooks, providing insights into how tools, rules, community, division of labour, and the object of the activity interact within an educational setting. This framework not only allows researchers to examine how e-textbooks function as tools within the teaching–learning process, but also to identify the systemic contradictions that may arise. These contradictions between traditional pedagogical practices and new technological tools, for instance, are particularly important, as they highlight the challenges educators and students face when adapting to technological changes.

By using CHAT as a framework, researchers can continue to unpack how technological changes, such as the introduction of e-textbooks, extend beyond the classroom to influence teaching philosophies, institutional policies, and the overall structure of education. This makes CHAT not just a tool for analysing current educational technologies, but a valuable approach for examining the ongoing digital transformation of higher education in future studies.

This tertiary contradiction emerged from conflict regarding the lecturers’ perspectives on the role of e-textbooks in their teaching. While some saw e-textbooks as a supplementary tool, others feared the potential overshadowing of their traditional roles. Additionally, lecturers felt a tension between leveraging the e-textbook’s capabilities and maintaining their authoritative and guiding role in the classroom.

Furthermore, this contradiction between the e-textbook and the subject (lecturers) is multi-layered, marked by both conflict and a double bind. While e-textbooks present challenges, they also usher in opportunities for pedagogical innovation. However, for optimal outcomes, it is essential to address student concerns about using the text and effectively communicate the benefits of the e-textbook. The tertiary contradiction (a), between mediation means and division of labour, focuses on the transformative role of the e-textbook, prompting lecturers to adopt a more active role in designing meaningful learning experiences. Recognising and addressing these tensions can foster a productive integration of e-textbooks within the educational landscape. To resolve this tension requires a balanced approach, professional development, and training programmes that can equip lecturers with the necessary skills and strategies to effectively design and facilitate learning experiences that optimise the use of e-textbooks.

It would be valuable to discuss more prominently in future research the role of e-textbooks not merely as learning tools, but as a proxy for broader technological change within higher education. E-textbooks represent a shift in teaching practices, reflecting the ongoing digital transformation that is reshaping the educational landscape. By transitioning to e-textbooks, educators are engaging with new pedagogical approaches that require rethinking traditional methods of content delivery and student engagement.

This technological shift can influence teaching practices in several ways. Firstly, it encourages a move towards more interactive and flexible learning environments, where students can access materials from anywhere, at any time, fostering a more student-centred approach. Secondly, the integration of e-textbooks may impel educators to adapt their instructional strategies to leverage the multimedia and interactive capabilities these platforms offer. This can enhance student participation, engagement, and personalised learning experiences.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment (EBE) Ethics Committee (EiRC) of University of Technology (protocol code 16165892, June 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to privacy concerns access to the data is restricted and will only be provided to researchers who comply with the appropriate ethical guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Global Institute for Teacher Education and So-ciety at Cape Peninsula University for providing support for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author reported no conflicts of interest for this study.

References

- Simpson, Z.; Inglis, H.; Sandrock, C. Reframing resources in engineering teaching and learning. Afr. Educ. Rev. 2020, 173, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET). Teaching in a COVID-19 context: Challenges for CET lecturers. Webinar: A dialogue on contributing to lecturer professionalisation in Adult and Community Education and Training. Presentation by Mr David Diale, 26 March 2021.

- Winberg, C.; Garraway, J. Reimagining futures of universities of technology. CriSTaL 2019, 7, 38–60. [Google Scholar]

- Masango, M.M.; Van Ryneveld, L.; Graham, M.A. Barriers to the implementation of electronic textbooks in rural and township schools in South Africa. Afr. Educ. Rev. 2020, 17, 86–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S. Effect analysis of digital textbook on ability of self-directed learning. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Soft Computing and Machine Intelligence (IEEE), New Delhi, India, 26–27 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, J. The effects of digital textbooks on college EFL learners’ self-regulated learning. Multimed. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2017, 20, 99–126. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Wu, B.; Xu, X. Design, development, and learning in e-Textbooks: What we learned and where we are going. J. Comput. Educ. 2015, 2, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, J.A.; Moser, M.T.; Segala, L.N. Electronic reading and digital library technologies: Understanding learner expectation and usage intent for mobile learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2014, 62, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangen, A.; Van der Weel, A. The evolution of reading in the age of digitisation: An integrative framework for reading research. Literacy 2016, 50, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegenthaler, E.; Wurtz, P.; Groner, R. Improving the usability of e-book readers. J. Usability Stud. 2010, 6, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, K.H.; Lam, T.; Kam, B.H.; Nkhoma, M.; Richardson, J.; Thomas, S. The role of textbook learning resources in e-learning: A taxonomic study. Comput. Educ. 2018, 118, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watjatrakul, B.; Hu, C.P. Effects of personal values and perceived values on e-book adoption. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/ACIS 16th International Conference on Computer and Information Science (ICIS), Wuhan, China, 24–26 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Embong, A.M.; Noor, A.M.; Hashim, H.M.; Ali, R.M.; Shaari, Z.H. E-books as textbooks in the classroom. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 47, 1802–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schuh, K.L.; Van Horne, S.; Russell, J.E. E-textbook as object and mediator: Interactions between instructor and student activity systems. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2018, 30, 298–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horne, S.; Henze, M.; Schuh, K.L.; Colvin, C.; Russell, J.E. Facilitating adoption of an interactive e-textbook among university students in a large, introductory biology course. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2017, 29, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horne, S.; Russell, J.E.; Schuh, K.L. The adoption of mark-up tools in an interactive e-textbook reader. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2016, 64, 407–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockinson-Szapkiw, A.J.; Courduff, J.; Carter, K.; Bennett, D. Electronic versus traditional print textbooks: A comparison study on the influence of university students’ learning. Comput. Educ. 2013, 63, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, S.; Matthee, M. Implementation of electronic textbooks in secondary schools: What teachers need. In Proceedings of the International Association for Development of the Information Society (IADIS) 15th International Conference on Mobile Learning, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 11–13 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cardullo, V.; Zygouris-Coe, V.; Wilson, N.S.; Craanen, P.M.; Stafford, T.R. How students comprehend using e-readers and traditional text: Suggestions from the classroom. In American Reading Forum Annual Yearbook; American Reading Forum: St. Pete Beach, FL, USA, 2012; Volume 32, pp. 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Osih, S.C.; Singh, U.G. Students’ perception on the adoption of an e-textbook (digital) as an alternative to the printed textbook. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2020, 34, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, D.P.; Bates, M.L.; Gallo III, J.R.; Strother, E.A. Incoming dental students’ expectations and acceptance of an electronic textbook program. J. Dent. Educ. 2011, 75, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jao, C.S.; Brint, S.U.; Hier, D.B. Making the neurology clerkship more effective: Can e-Textbook facilitate learning? Neurol. Res. 2005, 27, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woody, W.D.; Daniel, D.B.; Baker, C.A. E-books or textbooks: Students prefer textbooks. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzyankina, E.; Simpson, Z. Digital literacy practices of engineering students using e-textbooks at a University of Technology in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (ProComm), Limerick, Ireland, 17–20 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnos, T.; Sheppard, S.D.; Billington, S.L. Integrating a digital textbook into a statics course. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), San Jose, CA, USA, 3–6 October 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Eveleth, L.; Stone, R.W. Usability, expectation, confirmation, and continuance intentions to use electronic textbooks. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2015, 34, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, R.Y.K.; Cheung, D.S.P.; Lau, W.W.F. The effects of electronic textbook implementation on students’ learning in a chemistry classroom. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Learning and Teaching in Computing and Engineering (LaTICE), (IEEE), Hong Kong, China, 20–23 April 2017; pp. 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, R.W.; Baker-Eveleth, L. Students’ expectation, confirmation, and continuance intention to use electronic textbooks. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 984–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Beltrán, M.; Tigert, J.M.; Peercy, M.M.; Silverman, R.D. Using digital texts vs. paper texts to read together: Insights into engagement and mediation of literacy practices among linguistically diverse students. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 82, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, K. Current Situation and Prospects for Physical Education in the European Union; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2007; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2007/369032/IPOL-CULT_ET(2007)369032_EN.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Gyllen, J.; Stahovich, T.; Mayer, R. How students read an e-textbook in an engineering course. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2018, 34, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, R. Why use textbooks? ELT J. 1982, 36, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.C. Curriculum Development in Language Teaching; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alibrahim, A.; Elham, A. Exploring intervention of e-textbook in schools: Teachers’ perspectives. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2022, 42, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Leont’ev, A.N. The problem of activity in psychology. Sov. Psychol. 1974, 13, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. Activity theory and individual and social transformation. In Perspectives on Activity Theory; Engeström, Y., Miettinen, R., Punamaki, R.L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. J. Educ. Work 2001, 14, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata-Lynch, L.C. Activity Systems Analysis Methods: Understanding Complex Learning Environments; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Engeström, Y. Expansive learning: Towards an activity-theoretical reconceptualization. In Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists in Their Own Words, 2nd ed.; Illeris, K., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 46–65. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, W.M. Activity theory and education: An introduction. Mind Cult. Act. 2004, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, C.L. Do Students Using Electronic Books Display Different Reading Comprehension and Motivation Levels than Students Using Traditional Print Books? Liberty University: Lynchburg, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Engeström, Y. From Teams to Knots: Activity-Theoretical Studies of Collaboration and Learning at Work; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Engeström, Y.; Sannino, A. Studies of Expansive Learning: Foundations, Findings and Future Challenges: Introduction to Vygotsky; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 100–146. [Google Scholar]

- Uden, L. Activity theory for designing mobile learning. Int. J. Mob. Learn. Organ. 2007, 1, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannino, A.; Engeström, Y. Co-generation of societally impactful knowledge in Change Laboratories. Manag. Learn. 2017, 48, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A. Working collaboratively to build resilience: A CHAT approach. Soc. Policy Soc. 2007, 6, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virkkunen, J.; Mäkinen, E.; Lintula, L. From diagnosis to clients: Constructing the object of collaborative development between physiotherapy educators and workplaces. In Activity Theory in Practice: Promoting Learning across Boundaries and Agencies; Daniels, H., Edwards, A., Engeström, Y., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 8th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y.; Sannino, A. Discursive manifestations of contradictions in organizational change efforts: A methodological framework. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2011, 24, 368–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, B.; Henderson, A. Interaction analysis: Foundations and practice. J. Learn. Sci. 1995, 4, 39–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S. Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2020, 49, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creanor, L.; Gowan, D.; Howells, C.; Trinder, K. The learner’s voice: A focus on the e-learner experience. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Networked Learning, Lancaster, UK, 10–12 April 2006; Banks, S., Hodgson, V., Jones, C., Kemp, B., McConnell, D., Smith, D., Eds.; Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=67c42bccec275e8b80cab006384135a518877d38 (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Laurillard, D. A conversational framework for individual learning applied to the ‘learning organisation’ and the ‘learning society’. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. Off. J. Int. Fed. Syst. Res. 1999, 16, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagorinsky, P. Vygotsky and Literacy Research: A Methodological Framework; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. The Collected Works of L.S. Vygotsky, Vol 1: Problems of General Psychology; Rieber, R.W., Carton, A.S., Eds.; Minick, N., Translator; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Smagorinsky, P. The social construction of data: Methodological problems of investigating learning in the zone of proximal development. Rev. Educ. Res. 1995, 65, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, J. Developing the repertoire of teacher and student talk in whole-class primary English teaching: Lessons from England. Aust. J. Lang. Lit. 2020, 43, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J. Displaced but not replaced: The impact of e-learning on academic identities in higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 2009, 14, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).