Abstract

Mexico has recently introduced the Nueva Escuela Mexicana (NEM) in Basic Education, which aims to create a more meaningful, contextualised, inclusive learning environment. This study examined stakeholder experiences and perspectives on the NEM in its first year of implementation. A total of 79 semi-structured individual and group interviews were conducted in 12 primary schools in three Mexican states. A total of 168 participants were interviewed: learners, teachers, head teachers, teacher trainers, and local and regional supervisors. This study found that stakeholders held a range of positive and negative views about the NEM reform. Participants reported several concerns, such as the lack of foundational knowledge developed through the new approach, doubts about certain curricular content (e.g., gender and sexuality), and a lack of explicit guidance and training. This paper offers policy recommendations, which may also be relevant to policymakers in other countries. Limitations of this study and recommendations for future studies are discussed.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Nueva Escuela Mexicana

The Nueva Escuela Mexicana (NEM—“New Mexican School” in English) is the national educational policy for all levels of Mexican state education from initial to higher education, which was formally implemented in the 2023–2024 school year. Official curriculum documentation [1,2] outlines four main characteristics of the NEM:

- Curricular integration. School subjects (e.g., maths, science, Spanish) are now combined into various “formative fields” (“campos formativos” in Spanish)—“Languages”, “Scientific Knowledge and Thinking”, “Ethics, Nature, and Societies”, and “The Human and the Community”. Within these fields, there is an increased focus on contextually relevant, interdisciplinary, project-based learning.

- Increased autonomy for teachers. The NEM explicitly encourages teachers to adapt the teaching and learning processes to the needs of their specific context and its learners.

- Focus on the community. The NEM stresses the importance of the school as the centre of the community, encouraging contextually relevant content and interaction with stakeholders within local contexts.

- Education as a fundamental human right: for all learners, regardless of background or individual differences.

Although some of the aforementioned principles have been present, to varying degrees, in previous iterations of the Mexican state curricula, the NEM nevertheless represents a significant departure from the priorities of previous curricular reforms, which placed more emphasis on meeting international standards and producing citizens to be competitive in globalised labour markets [3]. In contrast, the focus of the NEM advocates for a constructivist, humanistic, community-based approach, aiming to develop not only children’s cognitive abilities but also their values and socioemotional skills [4,5]. The NEM is said to be influenced by critical pedagogy and epistemologies of the South, placing an increased emphasis on inclusion, collaboration, democratic values, identity, honesty, respect, multiculturalism, interculturality, peace, environmental care, and social transformation [6].

Early reactions to the NEM proposal have been both positive and negative. Although there was some initial positivity about the reform [7], the proposal has also been met with disapproval. The NEM has been criticised for neglecting the importance of scientific knowledge [8], containing overly vague, unfamiliar terms, with a lack of clear guidance for teachers [9], as well as not being appropriate to the current state of post-pandemic educational conditions [10]. Some of this dissatisfaction has been on political grounds, with opponents arguing that the NEM aims to advance a progressive agenda to reshape national identity and values according to the ideologies of the current government [10,11]. An example of this is the inclusion of topics of gender and sexuality in the primary school textbook, which openly addresses matters such as homosexuality and transsexuality. Resistance to these culturally sensitive topics has led some states to refuse to distribute the textbook [12], and has even led, in some extreme cases, to parents publicly burning the new textbooks in protest [13].

Despite there being a great deal of commentary and controversy surrounding the Nueva Escuela Mexicana, very little empirical research has been conducted on its implementation. Although a limited number of small-scale studies have been conducted [5,14], the present study is, to our knowledge, the first of its kind to comprehensively explore stakeholder experiences and perspectives on the reform.

1.2. Literature Review: Factors Influencing the Implementation of “Learner-Centred” Educational Changes

The Nueva Escuela Mexicana is an example of an educational reform that shares certain characteristics with broader movements in education worldwide. Indeed, we would argue that it can be classified into the larger category of non-traditional, progressivist, or “learner-centred” reforms [15,16]. Learner-centred education carries eclectic concepts and is said to be difficult to define [17,18]. Based on the theoretical literature and empirical studies of 326 published articles, Bremner [15] identified six potential aspects of learner-centred education, namely (1) active participation (including interaction); (2) relevant skills (real-life skills and higher-order skills); (3) adapting to needs (including human needs); (4) power sharing; (5) autonomy (including metacognition); and (6) formative assessment.

Some of these learner-centred aspects can be observed in the principles of the NEM [1,2,5]. For example, the project-based approach advocated by the NEM inherently requires learners to be active and interact with the teacher, their classmates, and their communities. The focus is very much on skills that will be useful for them in real life, with higher-order skills such as creativity and critical thinking prioritised over lower-order skills such as knowledge and memorisation. The NEM is explicitly aimed to be context-based, with teachers and schools granted the autonomy to adapt the content of learning to their learners’ specific needs, including their holistic emotional needs from a humanistic perspective. Power inherently begins to move away from the teacher, as learners are invited to critique the status quo, offering their own opinions and solutions to real-life problems. Moreover, the NEM encourages learners to work independently and conduct research, as opposed to depending solely on the teacher to provide knowledge.

Mexico is not alone in introducing some or all of the aforementioned principles; indeed, learner-centred approaches have been introduced and encouraged in numerous countries worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [16,19]. However, although learner-centred approaches tend to be perceived positively by stakeholders [20], there tend to be few explicit links to more positive outcomes, possibly, in part, due to the lack of large-scale, methodologically rigorous studies examining learner-centred outcomes over time [19,21]. Moreover, there is a certain degree of stakeholder scepticism when it comes to implementing learner-centred approaches in “absolute” terms [22]. This has led some authors to argue that it would be preferable to focus on improving the effectiveness of previous teacher-centred approaches [23], whereas others have argued for a middle ground in which learner-centred approaches are combined with teacher-centred approaches depending on the needs and cultural beliefs of stakeholders in diverse contexts [24,25,26]. It should be stressed that “learner-centred” and “teacher-centred” are not necessarily binary opposing terms and we might more usefully characterise different teaching and learning practices as being on a continuum between more and less learner-centred practices [16]. Moreover, it is important to reiterate that interpretations of learner-centred approaches may vary considerably between contexts, teachers, and age groups, among other factors [15].

Key concepts from the educational change and policy implementation literature may help us understand the factors that influence the degree of implementation of the Nueva Escuela Mexicana and similar learner-centred reforms. Fullan [27] highlights the important point that a great deal of emphasis is typically placed on the “what” of the change (i.e., the content of the change itself) and relatively little on the “how” (i.e., the procedures and processes required for teachers to actually implement the change). Spillane et al. [28] stress the importance of teachers’ sense-making, arguing that policy implementation ultimately depends on how stakeholders interpret the meanings of the changes. These interpretations vary depending on people’s prior experiences and the contexts in which they are interpreted [29], which ultimately have a significant bearing on how educational changes are implemented. Relatedly, Fullan and others [27,30,31] have emphasised the importance of teachers believing in the value of the espoused changes. When there is misalignment between stakeholders’ current beliefs and those implied by the change, it can understandably lead to resistance [32,33]. Moreover, even when there is some degree of teacher buy-in for the desired changes, a lack of coherence between various aspects of the education system often restricts teachers’ abilities to put beliefs into practice [24,30].

In relation to this lack of coherence, Wedell [31] sought to distinguish between the “parts” of the system (i.e., those parts of the system that may constrain or enable change) and the “partners” of the system (i.e., those people in the system that may constrain or enable change). These “parts” and “partners” were further analysed by Sakata et al. [20] through their systematic review of learner-centred education implementation, creating a framework of enablers and constraints of implementation in different societal layers. Regarding the “parts” of the system, classroom-level constraints included insufficient classroom resources [34,35], inappropriate resources [36,37], inadequate infrastructure [38,39], overcrowded classrooms [30,40], and a range of learner levels in the same classroom [34,41]. Policy-level constraints included poor communication of key messages [39,42], which often led to inconsistency of understanding of key concepts [43,44], a lack of time to cover the curriculum [30,36], and examinations that contradicted the changes [35,45]. Regarding teacher recruitment and development [46], constraints included a shortage of qualified teachers [37,42], poor working conditions [36,40], insufficient teacher training [37,39], short and superficial teacher training [43,47], a lack of follow-up to initial sessions [34,48], passive, unengaging training [37,48], a lack of practical experiences [40,41], a lack of flexibility to adapt to the context [37,44], and a lack of opportunities for teachers to collaborate [41,43]. Conversely, more successful teacher training experiences were those that were longer, incorporated ongoing support [49,50], were active and engaging, incorporated practical experiences such as observation and teaching practices sessions [33,51], included opportunities for teacher collaboration [51,52], and incorporated opportunities for teacher reflection, especially regarding the flexibility and autonomy to adapt learner-centred principles to their own teaching contexts [50,53].

Regarding the “partners” in the system, individual-level constraints included teachers’ lack of beliefs in the value of the change [30,36], a lack of teacher motivation [32,40], a lack of teacher experience [32,47], learners’ lack of familiarity with the change, as well as poor behaviour in class [35,47]. Conversely, individual-level enablers included teachers’ buy-in to the change [38,54] and learners’ motivation and enthusiasm [50,55]. At the school level, school leaders’ level of commitment to the change was cited as both an enabler [43] and a constraint [34,45], as well as support from other teachers, which was also cited as an enabler [43] and constraint [32,48] when trying to implement learner-centred education. At the policy level, policy officials’ level of support was also cited as an enabler [52,54] and constraint [35,37] on implementation, whilst at the wider society level, parental support was cited as a crucial factor in successful or unsuccessful implementation [45,53].

1.3. Gap in the Literature

As outlined in the previous section, numerous case studies have reported on the implementation of learner-centred changes in various countries, identifying a number of salient enabling and constraining factors. However, to date, there has been a dearth of studies conducted on the implementation of learner-centred approaches in Latin America and Mexico more specifically. For this reason, and given the relatively recent introduction of the Nueva Escuela Mexicana reform, which incorporates various learner-centred principles, this study provided an opportunity to study the implementation of a learner-centred educational change process in this relatively under-researched geographical and cultural context.

To date, there has been a relatively low number of academic publications on the NEM, partly due to the fact that formal implementation only commenced in the 2023–2024 school year. The few academic publications that do exist on the NEM have tended to provide non-empirical, theoretical reflections, documentary analyses, or reviews of the model [4,6,56,57,58,59]. A small number of studies have presented stakeholder perspectives on the NEM, but these have been very small-scale and restricted to narrow contexts [5,14]. With the previous in mind, the present study is, to our knowledge, the first of its kind to comprehensively examine stakeholder perspectives on the NEM. The following section outlines the methods we adopted to examine such perspectives.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aims and Research Questions

This article reports the findings of a broader research project exploring historically nurtured and currently valued pedagogies in different educational contexts [60]. Given the somewhat unique and time-critical circumstances of the introduction of the Nueva Escuela Mexicana in 2023, the researchers added an explicit focus on stakeholders’ experiences and perspectives on the NEM reform. The research question guiding this study was as follows:

What are stakeholder experiences and perspectives on the Nueva Escuela Mexicana reform in primary education?

2.2. Summary of Methodological Approach

In order to answer the research question above, a qualitative methodological approach was adopted, under a broadly interpretivist epistemological framework. Such an approach was suitable for the aims of this study as it sought to examine the participants’ perspectives and meaning-making [28] regarding their lived experiences of beginning to implement the NEM reform. This naturalistic, exploratory approach embraced participants’ subjective interpretations of the phenomenon in question, inviting them to express in-depth, rich, contextually bound expressions of their experiences [61,62].

We had initially considered complementing the qualitative component of this research by conducting quantitative surveys containing pre-established, deductive categories, which would have gathered less detailed information but from a larger number of participants. However, we ultimately decided that qualitative methods, specifically through interviews and group interviews, were better aligned with the exploratory nature of this study, in which themes relating to the lived experiences of implementing the NEM would emerge inductively from the participants themselves.

2.3. Context and Participants

Data collection was conducted at a total of 12 primary schools in three Mexican states: Nuevo León, Hidalgo, and Chiapas. These three states were chosen due to their relative geographical, economic, and cultural heterogeneity. Although we were not aiming to achieve a statistically representative sample, we were interested in obtaining as wide a range of perspectives as possible (“triangulation of sources” [62]). We visited four schools per state, including at least one urban, semi-rural, and rural school; again, this was to allow for a plurality of perspectives to emerge. Schools were selected by convenience sampling. Through existing online networks with primary school leaders and teachers, Author 1 sent an open call for participation to interested schools. We were subsequently put in touch with local contacts, who facilitated permissions and access to the 12 primary schools.

Within each school, we aimed to interview (1) at least two groups of at least five primary school learners; (2) at least two teachers; (3) at least two parents; (4) the head teacher; (5) where possible, a school-based teacher trainer (“asistente técnica/o pedagógico/a in Spanish”); and (6) where possible, a local supervisor/superintendent (“supervisor(a)”/“inspector(a)”). In one school in Nuevo León, we also interviewed a deputy head teacher, whilst in Hidalgo, we were also able to interview a regional supervisor (“jefe de sector” in Spanish). Within each school, we asked to interview teachers who possessed a range of experience and across genders. For example, in each school, we typically interviewed one male and one female teacher, one of whom had fewer than 10 years’ experience, and the other who had more than 10 years’ experience. For the learner group interviews, 4th-grade (ages 9–10), 5th-grade (ages 10–11), and 6th-grade (ages 11–12) learners were chosen, as we felt younger learners may have been less able to articulate their views on their valued teaching and learning approaches. Table 1 summarises the participants we interviewed:

Table 1.

Summary of study schools, participants, and interviews.

2.4. Methods of Data Collection

The data collection process took place between October 2023 (four schools in Nuevo León and one in Hidalgo) and January 2024 (three schools in Hidalgo and four in Chiapas). This meant that participants had been subject to the NEM reform for approximately two to six months at the time of data collection; understandably, the schools we spoke to in January may have been more accustomed to the reform as they had additional time putting it into practice. Each school visit lasted one to two days, during which time we interviewed as many participants as possible over the course of the school day. Interviews were appropriate for the aims of this research as they allowed the participants to express their lived experiences of the NEM reform in their own words [63]. The semi-structured nature of these interviews allowed us the flexibility to adapt to participants’ responses and explore emerging topics where relevant, in line with the exploratory, qualitative approach underpinning this study [61,64].

School head teachers kindly allowed us private spaces (for example, an empty classroom or a staff room) in order for us to conduct the interviews in a confidential, non-threatening environment. Interviews were individual in the case of teachers, head teachers, and supervisors; parents took part in group interviews of two (with one exception in which five parents arrived and were keen to participate), whilst learners took part in groups of four or five. A total of 79 individual interviews and/or group interviews with a total of 168 participants were conducted.

The main aim of the interviews was to ascertain stakeholders’ experiences and perspectives on the NEM. The types of questions asked in the interviews varied slightly depending on the type of participant, but the main foci (aside from introductory, warm-up, and closing questions) are summarised below (please note that learner group interviews were more simplistic, asking questions about learners’ general positive and negative experiences in the classroom and at school more generally).

- What knowledge, skills, values, etc., do you think children should gain from primary education?

- In order to achieve the previous knowledge, skills, values, etc., what sort of teaching and learning approaches should take place in the classroom?

- To what extent is it possible to implement these teaching and learning approaches, and why?

- Can you describe your understandings and experiences of the Nueva Escuela Mexicana?

- Concretely, what is done differently under the NEM compared to what was being done previously?

- Do you consider the NEM to be a positive change? Why/why not? Do you prefer the NEM compared to previous approaches? Why/why not?

Interviews were conducted in Spanish by Author 1. Interviews were audio recorded (no video recordings were taken) and lasted between 8 and 68 min, with the majority lasting between 30 and 50 min.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for carrying out this research was granted by the Hiroshima University Research Ethics Committee on 12 May 2023. Permission to conduct this research was then provided by the relevant educational authorities before the researchers entered schools. Voluntary and informed consent was acquired through participant information sheets and consent forms, which were also explained verbally to participants. Regarding permissions to interview learners, we acquired head teacher consent, who obtained consent from learners’ parents. Strict anonymity and confidentiality protocols were followed; no personal identifying information is included in any public-facing documents.

2.6. Data Analysis

Audio recordings were automatically transcribed using the transcription software Notta (version 3.28) before being rigorously checked and post-edited by a native Spanish speaker. The Spanish transcriptions were then automatically translated into English using the translation software DeepL (version 24.3). Whilst there were naturally some inaccuracies with this automatic translation, this proved a very cost-effective and time-effective way of obtaining an initial idea of the main themes emerging from the data. The translations of any excerpts used in this final report were carefully checked by Authors 1 and 3, who are highly proficient in both languages.

All translated transcripts were inputted into the qualitative data analysis tool NVivo. Authors 1 and 2 concurrently conducted their own processes of inductive thematic analysis. This analytical approach was appropriate for the aims of this study as it allowed participants’ experiences to emerge from this study without there being a pre-established framework [65,66]. This process involved the researchers carefully reading the transcripts of each of the interviews and creating relevant themes and sub-themes as they emerged, selecting illustrative segments of interview text as examples of each theme. As the researchers proceeded to analyse subsequent interviews, similar themes (i.e., themes that emerged more than once in different interviews) were grouped together. Over a period of several weeks, the researchers re-read and re-created the themes and sub-themes through an iterative process [65,66]. At the end of this process, the segments of text coded in each theme were read through to check whether they had been categorised appropriately.

Given the inductive nature of the analysis, it was unrealistic to expect that the exact themes and sub-themes created would be identical between Authors 1 and 2. Indeed, the quantitative notions of inter-rater reliability are not appropriate given the exploratory, qualitative nature of this study [64]. However, in order to increase the trustworthiness of the findings, each author conducted “analyst triangulation” [62], which involved them sending their NVivo files to the other for detailed checking. Subsequently, the two researchers met and engaged in a process of constructive dialogue. The purpose of such dialogue was not to agree upon unequivocal “right” answers, but rather to understand how different researchers might have different perspectives on the data, to identify any potential blind spots in the analysis, and to resolve any emerging doubts about their interpretations of the data. Through such a process, Authors 1 and 2 ultimately agreed upon each of the main themes that are presented in the following Results section.

2.7. Maximising Trustworthiness

We endeavoured to maximise the “trustworthiness” in this qualitative study through several means. In order to enhance the credibility of the findings, we utilised triangulation of sources, analyst triangulation, and peer debriefing [62,64]. Firstly, regarding triangulation of sources, we aimed to increase credibility by collecting a relatively large sample from a range of different stakeholders (learners, parents, teachers, teacher trainers, head teachers, local, and regional supervisors) in different geographical, economic, and cultural regions of Mexico, and from urban, semi-rural, and rural areas within each region. Secondly, regarding analyst triangulation, as mentioned in the previous sub-section, two authors analysed the data concurrently and then met to share perspectives. Thirdly, we conducted peer debriefing; this involved giving our interpretations of the findings to a disinterested experienced colleague at Author 1′s institution for critical feedback, as well as presenting initial themes at an international conference where we received critical feedback. Unfortunately, given that we had relatively little time to visit all 12 schools, we were not able to share our interpretations of the findings with the participants for member checking [64].

2.8. Limiting Bias and Researcher Positionality

In addition to the previous strategies to increase credibility, we also aimed to maximise confirmability [64] by not expressing our personal views on the subject and striving, where possible, not to ask “leading” questions [63]. Moreover, in this paper, we aim to be as transparent as possible about our own positionality so that the reader may judge for themselves the extent to which our interpretations may have been shaped by bias.

Author 1 is a UK national currently working at a UK university; however, he has extensive experience and knowledge of the Mexican education system and the Spanish language, having lived in Mexico for several years. He has an inherent interest in more learner-centred pedagogies, but, as reflected in his published work [15,24], he is open-minded regarding the potential value of more traditional, teacher-centred pedagogies. Author 2 is a Japanese national currently working in a Japanese university, who initially had relatively little knowledge of the Mexican education system. Like Author 1, she has been critical about the naive adoption of learner-centred pedagogies in different contexts and has explored the nexus between learner-centredness and locally valued pedagogies, as represented in her published work [67]. Authors 1 and 2 might be considered, by some, to be “outsiders”, with relatively little knowledge of the Mexican context (though Author 1 did live in Mexico for several years). On the other hand, their “outsider” status may have allowed for a “fresh set of eyes” to look at the phenomenon, through a relatively neutral lens. Finally, Author 3 is a Mexican national and a member of the National System of Researchers (SNI in Spanish). Author 3 did not participate directly in data collection; however, she supported Authors 1 and 2 from an organisational perspective before, during, and after data collection, providing context-specific knowledge of the Mexican education system. Author 3 is not affiliated with any Mexican political party.

3. Results

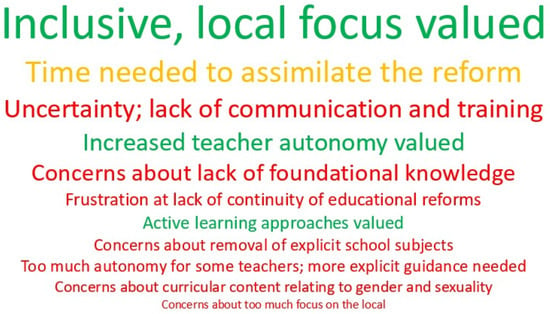

In the results section that follows, we present the most commonly cited themes emerging from the stakeholder interviews. Figure 1 below lists each of these themes; the larger the text size, the more times the theme was cited. Please note that the intention of Figure 1 is to provide a quick visual overview of the main themes that were mentioned by participants; the exact numbers are not essential, and they have not been included due to the qualitative, exploratory nature of this study [61,62].

Figure 1.

Word cloud summarising key themes.

In the sub-sections that follow, we begin by providing a general overview of the overall perspectives on the reform (Section 3.1). We then focus on participants’ perspectives on active learning approaches (Section 3.2), before examining participants’ perspectives on inclusive, local approaches (Section 3.3). We continue by discussing participants’ perspectives on increased teacher autonomy (Section 3.4), and we conclude by presenting their perspectives on the process of reform implementation (Section 3.5). A selection of quotes has been included to support each point made. Due to limitations of space, it has not been possible to include quotes for all points, but we have endeavoured to include excerpts that are particularly illustrative of the themes discussed.

3.1. Overall Perspectives on the Reform

The participants we interviewed expressed a range of positive, negative, and mixed views on the NEM. Some expressed a great deal of optimism and enthusiasm about the reform, whereas in a few cases, some were strongly in opposition to the reform. In terms of overall perspectives on the reform, we did not detect meaningful differences across the three states, between urban and rural areas, or across participant types.

There were many cases in which participants expressed their support for the aims of the NEM. Optimistic language included describing the NEM as “positive” (e.g., Teacher 23, urban Chiapas), seeing the reform as the “correct” way forward (e.g., Head Teacher 4, rural Nuevo León), or simply using phrases such as “I like the new educational model” (Parents GI8, semi-rural Hidalgo), which were common. Conversely, participants who were more negative about the NEM tended to compare it to previous programmes, stating that it would be worse than what had been implemented previously (e.g., Local Supervisor 1, urban Nuevo León; Teacher 11, semi-rural Hidalgo). Several senior figures cited that there had been a degree of reluctance from teachers about implementing the NEM (e.g., Head Teacher 9, rural Chiapas). Finally, a small number of participants vehemently expressed their dislike for the programme, such as Teacher 20 in rural Chiapas, who branded the NEM “awful” and a “failure”.

Time Needed to Assimilate to the Reform

The majority of participants we interviewed occupied the middle ground, recognising there are good and bad aspects of the reform (e.g., Parents GI8, semi-rural Hidalgo). Many participants expressed that they were not yet able to voice an informed opinion about the NEM, but they were willing to give the NEM a chance before making up their minds (e.g., Parents GI5, urban Hidalgo). A very common theme was for participants to describe the NEM as a “process” (e.g., Head Teacher 12, rural Chiapas) and to stress that teachers were gradually getting used to the change over time. This was exemplified by Local Teacher Trainer 1 in urban Nuevo León, who recounted how there was a lot of reluctance, including from himself, when the NEM was first introduced. However, after more closely inspecting the textbooks, he reached a more balanced view, discovering aspects in the new materials that he felt were positive. When interviewed, he emphasised that the NEM represented a significant challenge for many of his teachers, but he nevertheless expressed optimism about it:

It is a change of ideology; of paradigms; of how we perceive education. […] They are still experimenting. […]. It is a difficult task; it is a challenge; but I believe that step-by-step we are going to achieve it.(Local Teacher Trainer 1, urban Nuevo León)

This initial section has provided an overall flavour of the general views on the NEM. In the following sections, we examine some more specific reasons for these positive and negative perspectives. We begin by focusing on participants’ views on active learning approaches, one of the cornerstones of the NEM.

3.2. Perspectives on Active Learning Approaches

Active learning approaches, especially through project-based learning, represent one of the fundamental pedagogical underpinnings of the NEM. These projects are designed to be interdisciplinary, combining school subjects like maths and science into “formative fields” [1,2]. In this sub-section, we outline participants’ generally positive views on active learning approaches, but also highlight some participants’ concerns.

3.2.1. Active Learning Approaches Valued

Across the different regions, participants expressed positive views on the active learning approaches espoused by the NEM. For example, Teacher 5 in urban Nuevo León expressed her “love” for what her learners were engaging in through the new project work. Some participants related project work to increased learning. For example, parents in Group Interview 6 in rural Hidalgo appreciated the change from more “theoretical” approaches to new one that, from their perspective, helped the learners relate scientific concepts to real life. Teacher 8 in rural Nuevo León reflected on how the projects were different to what she had been delivering previously, and concluded that the topic area had been better understood in comparison to previous years:

I saw a lot of understanding after they did all those activities; […] they were really telling me what it was about in their own words […] I feel that it stayed with them more than in other activities.(Teacher 8, rural Nuevo León)

Learners were also very positive about active learning projects across all three regions that we visited. The most common reason for this was that learners valued working together in teams (e.g., Learners GI3, urban Nuevo León; Learners GI9, urban Hidalgo). The learners provided many examples of activities that they particularly appreciated. To give just one example, learners in rural Chiapas mentioned a project in which they had to design a recipe: “I liked that activity very much because I was with my friends, we got into teams, each one brought a recipe, we wrote, we drew, we painted” (Learners GI18, rural Chiapas).

Despite these positive views, participants also highlighted some concerns with project-based approaches. These concerns are highlighted in the following two sub-sections.

3.2.2. Concerns about Lack of Foundational Knowledge

The most commonly cited concern was that foundational knowledge was being neglected under the NEM. Teacher 7 in rural Nuevo León was keen to stress that “essential learning: Spanish and Maths; learners learning to count, divide, subtract, multiply, fractions” was not explicitly included in the projects. This was also summed up well by another teacher in rural Hidalgo:

There is not something specific that says: “teach him to read first with the alphabet”, “now teach him to form syllables”, “now teach him to count”. […] If my child doesn’t know how to read, how am I going to apply this project?(Teacher 13, rural Hidalgo)

In sum, learners did not always have the essential building blocks to pick up the higher-order skills that were supposed to be developed through the NEM projects. We especially found this to be the case when interviewing participants in rural schools, but this was also regularly mentioned in semi-rural and urban areas. For example, Head Teacher 2 in urban Nuevo León expressed that with the NEM, she felt “more lost” than in previous programmes. She argued that neglecting the explicit teaching of foundational knowledge meant teachers were not going into subjects in sufficient depth, meaning that essential contents were only “half-understood” and “half-learnt”.

This was perceived to be especially important for the earlier years of primary school, with many participants arguing that projects were simply not feasible until basic literacy skills were developed. This is exemplified in the following quote from Head Teacher 3:

The projects are very cool, very fun, I like them a lot. […] But in order to do them, I tell you, they need to be able to read and write.(Head Teacher 3, urban Nuevo León)

In light of these challenges, many teachers expressed that they had decided to avoid project-based work until they had made progress in developing their learners’ basic literacy. For example, Teacher 9 in urban Hidalgo stressed that most of her learners had not had any access to reading and writing before starting primary school. She explained how she had decided to exclude certain activities in the NEM textbook, and had set aside additional hours per day to teach her learners to read and write. The dilemmas teachers faced in implementing active learning through projects were further exemplified by a teacher in rural Chiapas, who simply did not feel she could implement projects until they had developed basic reading and writing:

They are little children and for me to do a project my children have to at least know how to hold a pencil. […] The system is telling me to work through projects […] but I haven’t touched the books. […] I am going to go at my own pace and at the pace of my children.(Teacher 17, rural Chiapas)

Participants’ concerns about the lack of foundational knowledge were linked to their disapproval of explicit school subjects being removed and replaced by interdisciplinary “formative fields”. We address this related issue in the following sub-section.

3.2.3. Concerns about Removal of Explicit School Subjects

Another key component of the NEM is the combining of separate school subjects (maths, science, etc.) into broader, interlinked “formative fields” (“campos formativos” in Spanish) [1,2]. However, several participants expressed that they preferred the previous system. This theme was especially prominent in the group interviews with parents. Parents expressed their concerns that the NEM had left out important subjects, with the lack of explicit maths content a particular worry (e.g., Parents GI7, rural Hidalgo). One parent in urban Nuevo León expressed their frustration with the combining of subjects:

I personally find it very annoying that the subjects are no longer separated. In a single project they see Maths, Natural Sciences, Geography, but the child no longer sees them as separate things. […] He says “yes, I’m learning, but I don’t know what I’m learning”.(Parents GI2, urban Nuevo León)

The quote above suggests that the combining of individual subjects into formative fields had led some parents to doubt whether much tangible progress was being made in their learning. This was also reflected in our discussions with learners. In fact, issues with the new textbooks was one of the most commonly emerging themes for learners in the learner group interviews. The general consensus was that the previous textbooks were better, and that the combined formative fields were somewhat difficult and confusing (e.g., Learners GI11, semi-rural Hidalgo). One learner from Group Interview 22 in urban Chiapas explained that “The only thing [she] would like to change in school is to go back to the old books.” She described the way information was presented to her as more “scrambled”, stating that she preferred the old books because they “gave clearer information so that you understood what you had to do.” This reflected the desire of many learners to have a more structured approach to their learning.

In the next section, we examine another key characteristic of the NEM approach: the increased focus on inclusive and local approaches.

3.3. Perspectives on Inclusive, Local Approaches

In addition to the focus on active learning approaches, the new curricular model of the NEM also places significant emphasis on inclusive and local approaches. These approaches include valuing all people in Mexico, regardless of their regional or individual characteristics, as well as placing more value on the “local”, i.e., not being so dependent on external forces and instead prioritising the needs of local communities [1,2]. As demonstrated in the following sub-sections, these approaches were generally well-received by the participants; however, some participants expressed some concerns.

3.3.1. Inclusive, Local Approaches Valued

The most commonly cited theme in the entire study was that participants were generally positive about inclusive and local approaches. With a few specific exceptions in Nuevo León, there was agreement across different participant types, regions, and urban, semi-rural, and rural areas. Participants emphasised the importance of children valuing Mexico, its culture, and its history: “how we are, and why we are, Mexicans” (Parents, GI5, urban Hidalgo). Participants expressed the need to “preserve” the rich Mexican culture, as well as the need to recognise and value “all that diversity of cultures” (Head Teacher 5, urban Hidalgo). Overall, such approaches were seen as a way “re-valuing” the peoples and cultures of Mexico “and, above all, to promote respect and equality” across the country (Teacher 8, rural Nuevo León).

Many participants shared their desire to “rescue” elements of the culture that had been “lost”, in particular indigenous languages that were starting to become extinct (e.g., Head Teacher 6, semi-rural Hidalgo). Related to this, participants mentioned the role that schools might play in not just sharing “scientific” but also “popular” or “ancestral” knowledge (e.g., Head Teacher 8, semi-rural Hidalgo). Indeed, it was seen that embracing such diversity, and rescuing ancestral knowledge was important in preserving people’s “identity”, belonging, and value for themselves (e.g., Teacher 11, semi-rural Hidalgo).

The notion of (re-)valuing oneself was related to the idea that Mexico would not have to be dependent on others, and that solutions could be found from within. This was linked to concepts of “decolonisation” and “emancipation” by some participants:

Our culture is a great culture, and this does not mean that Europe, Asia, the rest is no longer good, […] but things are good here too. That is the famous decolonisation.(Local Supervisor 4, urban Chiapas)

They are calling it “emancipation”, […] because Mexico has always obeyed other educational systems […]. We copy their system from other countries and that’s the problem. […] This is why the New Mexican School is important, because the community of the context is what the child will immediately appropriate.(Head Teacher 12, rural Chiapas)

More broadly, the aforementioned themes highlight the widespread desire for Mexicans to develop a more critical stance towards themselves, their country, and their futures:

It is important to create critical thinking, to break with those schemes that have traditionally been instilled in us, so that the child becomes more reflective, […] to give him the tools so that he can break those schemes and make sense of his reality by himself.(Teacher Trainer 4, urban Hidalgo)

Indeed, some participants suggested that the focus on critical thinking did not go far enough, for example, one parent who suggested that Mexican education should provide more accurate depictions of Mexican history (e.g., Parents GI5, urban Hidalgo).

Although the theme of inclusion and focus on the local was generally agreed upon, there was some degree of scepticism by some participants who felt there might be too much focus on the local. We briefly discuss these concerns now.

3.3.2. Concerns about Too Much Focus on the Local

As mentioned above, the notion of valuing inclusive and localised approaches was generally supported by most participants in this study. However, in Nuevo León, a state in the north of Mexico relatively close to the United States, there was comparatively less enthusiasm for certain aspects. For example, although most participants were very positive about promoting Mexican values and more contextually relevant learning, there were some doubts about taking too much time to learn about indigenous cultures and languages. For example, parents in Group Interview 2 in urban Nuevo León highlighted that indigenous topics were not particularly relevant, given that it was actually very rare for their children to interact with indigenous people. This would seem to contradict the notion of focusing on local needs; indeed, parents suggested that it would be more relevant for their children to learn about the United States and the English language. Moreover, some parents suggested that indigenous topics were taught in quite a superficial way, for example, only teaching a few words in an indigenous language that the children would never use.

It was not only in Nuevo León that some participants offered counterpoints to the general positivity about focusing on the local. For example, parents in in urban Chiapas argued that it was important not only to focus on “within” but also being open to outside cultures. This is exemplified in the following quote from a parent:

We can’t just learn from ourselves. […] It is very important […], that they feel that they are part of here […] but also that they feel that it is not the only thing in the world.(Parents GI11, urban Chiapas)

A further concern expressed by some participants related to specific curricular contents, in particular, those on gender and sexuality. We examine these concerns now.

3.3.3. Concerns about Curricular Content Relating to Gender and Sexuality

A regularly cited concern with the NEM’s focus on inclusion and diversity was the issue of gender and sexuality. For many topics, the new textbooks adopt quite liberal views on gender and sexuality issues, such as openly promoting homosexuality and transsexuality, which was one of the main reasons cited for the protests about them [12]. Whilst many participants were keen to distance themselves from more extreme acts such as burning books, and many openly stated they had no problem with homosexuality and transsexuality, the general consensus was that it was not appropriate for these topics to be taught as early as primary school.

For example, Local Teacher Trainer 1 in urban Nuevo León interpreted the NEM textbooks to be promoting a “gender ideology” that he felt was very problematic given the socially conservative culture of the country. Parents explained that their main issue with the NEM textbooks were the topics of sexuality, which they felt should not be taught at such a young age (e.g., Parents GI11, urban Chiapas). In many cases, these topics were simply not taught by the schools, despite them being in the textbooks. For example, Teacher 23 in rural Chiapas explained that they had reached an agreement with the parents to physically remove all pages of the book that related to gender and sexuality. This final example demonstrates how teachers were permitted the freedom to remove elements of the textbook that were not considered appropriate to the context in which they were teaching. This relates to the notion of autonomy and contextualisation, another fundamental characteristic of the NEM, which we address the following sub-section.

3.4. Perspectives on Increased Teacher Autonomy

An important component of the NEM, explicitly identified in its curriculum documents, is the notion that teachers should have the flexibility and autonomy to adapt classes based on the perceived needs of the learners [1,2]. For example, in reference to the previous two sections, teachers were permitted to teach foundational knowledge instead of and/or in addition to implementing projects, and they could steer clear of controversial topics such as those related to gender or sexuality. As discussed in the following sub-sections, this autonomy was generally viewed positively, but some teachers found the transition towards autonomy to be challenging.

3.4.1. Increased Teacher Autonomy Valued

In general, the idea that learning could be adapted to local contexts, with teachers having the freedom to adapt the content and pedagogical approach, was well-received. Many teachers expressed that they agreed with the ability to contextualise their learning, as this made it easier for their learners (e.g., Teacher 10, urban Hidalgo). In fact, many teachers expressed that this was the aspect of the NEM reform that they liked the most, as it “gives you as a teacher the freedom to see that this works for my children and this doesn’t” (Teacher 23, rural Chiapas). The idea that teachers should be allowed to adapt to learner needs was also recognised as important by parents (e.g., Parents GI11, urban Chiapas).

As mentioned earlier, the freedom granted to teachers to adapt to the context somewhat mitigated the concerns stakeholders had with the aforementioned issues, such as a lack of foundational knowledge, gender, and sexuality. This contributed towards some teachers feeling less worried about contents of the NEM textbooks that they did not agree with. The textbooks became more of an optional resource, as explained by a teacher in urban Nuevo León:

I don’t think the books are bad; I think they come with many possibilities for the teacher to decide what he or she can and can’t do.(Teacher 6, urban Nuevo León)

For some teachers, this also alleviated some of the pressures they were feeling to meet standardised learning targets, which had been foregrounded in previous curricula. For example, Teacher 8 from rural Nuevo León reflected on how teachers had been expected to follow the curriculum more rigidly under previous programmes. This led her to feel “under pressure because you had to reach a certain point by a certain time.” She expressed that she appreciated the increased freedom afforded by the NEM, especially given that learners in rural areas often lacked the foundational knowledge and skills to engage in projects.

3.4.2. Too Much Autonomy for Some Teachers; More Explicit Guidance Needed

Despite generally positive views about increased autonomy, some challenges were identified by the participants. Several admitted that the process of becoming more autonomous was challenging, given that they had not been granted such freedom previously and were not sure what do with it (e.g., Head Teacher 12, rural Chiapas). For example, Teacher 15 in semi-rural Hidalgo admitted that he was “a little bit too dependent” on being spoon-fed what to do. He characterised teachers as more “technical” than “professional”, in the sense that they generally expected educational authorities to tell them what to do and how to do it.

In addition, some participants went as far as describing the NEM curriculum as “chaotic”. For example, a parent in Group Interview 11 in urban Chiapas felt that the previous programme was more “structured” and that the current one was “disorganised”, consisting of “too much chaos”. This was further exemplified by Teacher 2 in urban Nuevo León, who expressed that because there was “so much freedom, a lot of times you lose the focus”.

A few participants argued that it was not a teacher’s role to adapt curricula, stressing that it should be left to politicians or higher-level decision-makers. For example, an experienced teacher in urban Nuevo León reflected that she preferred a previous programme, which was much more explicit in telling her what to do:

I liked the ’83 programme. […] As a teacher it took you by the hand to what you wanted to achieve. Now with this one, it’s very “loose”. It’s like “do whatever you can” or “whatever you want”. […] We teachers are not political agents.(Teacher 1, urban Nuevo León)

Further concerns included how time-consuming and exhausting it was for teachers to design their own contextually appropriate programmes (e.g., Head Teacher 12, rural Chiapas), as doing so required extraordinary levels of commitment from teachers who were already overworked (e.g., Head Teacher 8, semi-rural Hidalgo). Moreover, in a few cases (e.g., Teacher 12, semi-rural Hidalgo), teachers argued that the NEM was, in fact, overly “prescriptive”, as teachers were being implicitly pushed towards certain content and pedagogical approaches, though this was not the majority view.

Despite the aforementioned concerns, the overall weight of feeling from the interviews we conducted was a degree of positivity towards the increased autonomy. Indeed, although some teachers were initially struggling with additional freedom, several suggested that, over time, they would become more used to it:

I feel that we have become so accustomed to everyone telling us what to do, that now that they tell you “I’ll give you the freedom to do it” we suddenly feel like we have no points of support. […] I think there can be a transition towards autonomy, but I think a gradual implementation works better, […] with the necessary support, especially with training.(Head Teacher 8, semi-rural Hidalgo)

The final words in the quote above indicate the importance of teachers receiving support in order to develop their autonomy. We address this final theme as part of the following sub-section.

3.5. Perspectives on the Process of Reform Implementation

The final set of themes relate to the ways in which the NEM was implemented in terms of communication, teacher training, and support. Unfortunately, the overwhelming consensus from participants was that the reform had been implemented in a less than effective way.

3.5.1. Uncertainty; Lack of Communication and Training

A regular comment across all regions and participants, even from those in leadership positions, was that they were not totally clear what the Mexican Ministry of Education was asking them to do. For example, Local Teacher Trainer 1 in urban Nuevo León explained that although they had been provided with some materials to read, there was “no person from above who told us ‘the reform consists of this’, as in all the previous reforms”. Indeed, he estimated that “out of ten teachers, eight don’t understand the reform.” Head Teacher 7 in rural Hidalgo explained that he had had very limited communication with the educational authorities, and had only received “seven or eight little sheets” explaining the aims of the reform in very general terms. Parents expressed that it had all come “as a bit of a shock” (Parents GI10, rural Chiapas) with very little information conveyed from above (e.g., Parents GI11, urban Chiapas).

Ineffective, inconsistent communications were cited as problems by many participants. For example, Head Teacher 3 in urban Nuevo León stated that they had been given one set of instructions in one information session, and then slightly different information in another session, and then further contradictory information in a third session. Local Supervisor 2 in rural Nuevo León explained how the information had started to come through, but on a “drip-feed basis”, without there being any clear, consistent or coherent messages. He expressed that any support or guidance “either arrived too quickly for us to transmit it, or it arrived late, or it didn’t arrive at all”, and recounted how he had attempted to consult with the educational authorities for clarity, but they were not able to provide any answers.

The most commonly cited issue was a lack of training provided by the Ministry of Education, not only for teachers but also for school leadership. Local Supervisor 3 in rural Chiapas summarised this by expressing that the NEM represented a “paradigm shift” in education, but without there being any “real systematisation of teacher training”. Deputy Head Teacher 1 in urban Nuevo León expressed how she had experienced numerous educational reforms, but that this was the one in which she felt least supported, given that there did not appear to be “an exclusive department that sent down the information from the system with a structured plan and a methodology”. Teacher 19 in rural Chiapas stated quite simply that that the difficulties in implementing the NEM had stemmed from them not receiving any training: “We were told: ‘here’s your programme—now we are going to implement it’”.

In those cases where training was provided, participants reported that it was not adequate, for example, owing to it being overly theoretical and not practical (e.g., Teacher 16, semi-rural Hidalgo), or that the trainers themselves were not sure about how to effectively apply the new principles (e.g., Head Teacher 6, semi-rural Hidalgo). Several participants highlighted their frustrations at not receiving teachers’ books to accompany the learner textbooks (e.g., Head Teacher 3, urban Nuevo León). In sum, the following quote encapsulates the feeling that whilst the NEM was promising in theory, its implementation had been neglected:

I think the New Mexican School is excellent; it was just badly planned.(Head Teacher 1, urban Nuevo León)

3.5.2. Frustration at Lack of Continuity of Educational Reforms

A final point highlighted by several participants was the frustration at the lack of continuity of the NEM and other reforms. Understandably, participants were hesitant to fully invest in the reform, given that it may be removed by future governments. For example, Teacher 11 in semi-rural Hidalgo stressed that every six-year electoral term tended to bring its own set of educational reforms, thus not allowing teachers to fully see if the new approaches were leading to any different results. This was reiterated by Teacher 18 in rural Chiapas, who lamented that there was “no continuity of the same educational model; […] no clarity; no goal.” Given that teachers naturally require time to assimilate to the changes, and with the constant expectation that new reforms may be replaced at any given point, it would seem natural that teachers may be more reluctant to put all of their efforts into the NEM.

Having presented the most commonly cited themes in this research, we now discuss the main findings and how they contribute to existing knowledge about the implementation of learner-centred educational reforms such as the NEM.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Main Findings

This qualitative study explored stakeholder experiences and perspectives on the Nueva Escuela Mexicana reform in Mexican primary education. The study provides an important contribution to knowledge, not only for national policymakers in Mexico but also for those implementing similar learner-centred changes in other countries.

The study yielded several important findings. Firstly, we found that there was a mixed reaction to the NEM: although there were many participants who were optimistic about the reform, there were also many who were less enthusiastic. Many participants recognised that time would be needed to more fully assimilate to the change, a point that consistently emerges in the wider educational change literature [27,31]. Indeed, many participants were inclined to feel positively about the change in theory, but were less convinced with the way it had been implemented in practice. These findings broadly align with the numerous case studies of learner-centred education implementation in low- and middle-income countries, in which there is a general sense of enthusiasm about learner-centred changes, but a wide range of factors constrain implementation [20].

The second key finding was that although participants tended to value the active learning afforded by the NEM’s active learning approach, they were concerned about the lack of learners’ foundational knowledge, in particular, literacy and numeracy skills. Moreover, there were concerns about combining the specific school subjects into interlinked “formative fields” (“campos formativos” in Spanish). This may be, to a certain extent, due to the fact that stakeholders still needed time to fully make sense of, and gain experience in, implementing the change [28,31]. However, it may be, also, that policymakers have failed to recognise the importance stakeholders place on learners possessing this foundational knowledge. These concerns are reflected elsewhere in the educational change literature, with many case studies suggesting the importance of combining more traditional approaches with more learner-centred approaches [26] or even abandoning such learner-centred approaches [23] at least until learners have the fundamental literacy and numeracy skills to engage in higher-order thinking. It should be acknowledged that the NEM reform does explicitly grant teachers this flexibility; for example, teachers explained how they had postponed working on elements of the book until they were satisfied their learners had acquired sufficient foundational knowledge and skills. One might argue that this approach is less “learnER-centred” and more “learnING-centred” [24,25], i.e., teachers themselves deciding which pedagogical approaches are most appropriate to meet the learning needs of their pupils, instead of uncritically following more learner-centred practices.

The third key finding was that stakeholders were generally very supportive of content related to inclusion and localised approaches. There was widespread agreement that primary education should aim to foster inclusion, equality, and respect for the diverse regions, peoples, languages, and cultures of Mexico. In addition to creating a more egalitarian society, it was argued by many participants that this would reaffirm Mexican community and identity, and perhaps reduce the tendency to feel that solutions have to come from outside Mexico. However, there were certain concerns that this may have gone too far, thus unnecessarily rejecting outside influences and the vital importance of scientific knowledge [8]. An additional concern was that specific topics of gender and sexuality were included in the primary school curriculum, which caused tensions with many participants. As recognised by participants, Mexico is, in many ways, a socially conservative country, and the perspectives of the participants we interviewed reflected this. The notion that stakeholder beliefs influence the degree of implementation of an educational change has been documented in many case studies in the literature, for example, in China [33], India [Brin2019], and Mexico [24]. Again, the important detail to recognise is that, as part of the overall principles of the NEM, teachers and schools are explicitly permitted to omit or adapt aspects of the change that may not be appropriate for local contexts [1,2].

This leads us to the fourth main finding, which related to the affordances, and challenges, of increased teacher autonomy granted by the NEM. In general, participants were supportive of the NEM’s emphasis on “focusing on the local”, in which teachers could contextualise learning to meet local needs. Likewise, many teachers also seemed to appreciate the increased autonomy that was afforded to them, with several commenting that this not only led to more meaningful learning but also reduced pressure on them to meet standardised targets. The idea of granting teachers the autonomy to adapt to local needs is regularly suggested in the educational change literature [50,53] and the findings of this study, to a certain extent, reaffirm this view. However, it is also important to note that some teachers did not always know how to manage such autonomy. Indeed, although it may not necessarily have represented a completely “revolutionary” change compared to what teachers were doing already, the NEM was generally seen as quite a departure from what had been promoted in previous reforms, especially regarding its inherent flexibility to allow teacher autonomy. The change was referred to by participants as a “paradigm shift”, and when there is a large difference between current and espoused beliefs, it is understandable that teachers may not be able to make the transition quickly [27,31]. Time is therefore essential in order for stakeholders to assimilate to changes over time; however, participants were particularly concerned that time might not be granted due to the lack of continuity caused by regular changes of government in Mexico. Furthermore, more guidance will be required in order to support teachers in adapting their classes to the context.

This leads us to the fifth and final main finding, which was the widespread uncertainty that surrounded the NEM reform. The participants of this study lamented inconsistent policy messages, a point that has reoccurred regularly in other case studies in a variety of contexts [39,42,44]. This lack of support was perceived by numerous stakeholders we interviewed, including parents, who had generally not been communicated with effectively, despite their crucial importance in facilitating educational changes [45,53]. Participants expressed their frustration in the general lack of training that was offered to teachers, a point that has been raised in many other studies [14,37,47].

In sum, it would appear that the Mexican Ministry of Education has become yet another system to dedicate too much time on the “what” of an educational change, and far too little time on the “how” [9,27]. In other words, decision-makers appear to have spent a great deal of time designing a change that would ideally bring certain benefits to Mexico, but they have not considered how to put the change into practice over time.

4.2. Policy Recommendations

In light of the previous discussion points, we offer the following recommendations to the Mexican Ministry of Education. As mentioned earlier, the NEM shares many key characteristics of similar learner-centred reforms, and as such, policymakers from other countries may also find these recommendations relevant.

- Address stakeholder concerns about perceived gaps in foundational knowledge: carefully consider the extent to which students may need basic knowledge in order to develop higher-order skills.

- Strengthen communication with parents and the wider public to make it clear what NEM does and what it does not do (despite some attempts to raise societal awareness of the reform, many parents were still very unclear on the aims and pedagogical approaches of the NEM).

- Provide more concrete training and support for teachers and head teachers, with a more consistent, unambiguous communication strategy. A particular focus here should be on supporting teachers in managing increased autonomy.

4.3. Limitations of this Study and Recommendations for Future Research

There were a few limitations of this study that must be acknowledged. First, the findings presented here represent just one snapshot of a particular time in the relatively early stages of implementing the NEM reform. The findings of this study should be treated with a certain degree of caution, given that it took place in the very early stages of change implementation, and given that conditions may have changed since the data were collected. This is particularly relevant given that teachers inherently need time to assimilate to and experiment with educational changes [27,31]. Future research should continue to evaluate the medium- and longer-term implementation of the NEM, as well as its potential outcomes in comparison to previous educational approaches.

Second, we did not employ member checking in this study, i.e., we did not give our findings to the participants themselves in order to check the extent to which our interpretations were accurate representations of what they wanted to express [36]. Future qualitative research on the NEM could include member checking in order to further maximise the trustworthiness of the findings.

Third, we were not able to interview those involved in the design of the curriculum or higher-level policymakers in order to gather their perspectives. Although we might argue that the most important stakeholders are those on the ground trying to assimilate to and implement the NEM reform, future research, perhaps with increased contacts in the Mexican Ministry of Education, may be able to complement our findings with policy-level perspectives.

Fourth, it might be argued that the participants expressed their thoughts on the reform more positively, consciously or unconsciously, in order to give the answers they felt we were expecting them to give. This argument is perhaps less convincing given that many participants openly expressed negative views on the reform. Moreover, given that we are not affiliated with any political party in Mexico, and assured participants that there would be no negative consequences for taking part in this study, it may have been that our “outsider” status could have been a benefit, not a limitation.

Finally, given that the main purpose of this study was to explore stakeholders’ perspectives on their valued pedagogies, we did not observe classrooms or conduct stimulated recall interviews. To extend the current study and to further triangulate the findings, future research could incorporate classroom observations and/or reflective interviews. Doing so would allow researchers and participants to specifically root their discussions in concrete classroom practices, as opposed to collecting self-reported perspectives on these practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.B. and N.S.; methodology, N.B. and N.S.; software, N.B. and N.S.; validation, N.B. and N.S.; formal analysis, N.B. and N.S.; investigation, N.B. and N.S.; resources, N.B. and N.S.; data curation, N.S.; writing–original draft, N.B. and L.S.B.M.; writing-review and editing, N.B., N.S. and L.S.B.M.; visualization, N.B.; project administration, N.B., N.S. and L.S.B.M.; funding acquisition, N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Fostering Joint International Research (A), 22K0207.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for carrying out this research was granted by the Hiroshima University Research Ethics Committee on 12 May 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymised versions of the datasets and codebooks used within this study are available on request.

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to the three expert Maestro/as who accompanied us in Nuevo León, Hidalgo, and Chiapas, providing expert localised knowledge and advice. For reasons of anonymity, we cannot share their names. We would also like to thank Mtro. Ramón Solórzano Robledo for his invaluable assistance. Finally, we would like to thank Scarlet Ramírez Herrera for meticulously checking the Spanish transcriptions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barbosa Xochicale, J. La Nueva Escuela Mexicana: Principios y Orientaciones Pedagógicas; Secretaría de Educación Pública: Mexico City, Mexico, 2023. Available online: https://dfa.edomex.gob.mx/sites/dfa.edomex.gob.mx/files/files/NEM%20principios%20y%20orientacio%C3%ADn%20pedago%C3%ADgica.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico. Plan de Estudio para la Educación Preescolar, Primaria y Secundaria. Available online: https://educacionbasica.sep.gob.mx/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Plan_de_Estudios_para_la_Educacion_Preescolar_Primaria_y_Secundaria.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Gobierno de la República, Mexico. Reforma Educativa. 2013. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/2924/Resumen_Ejecutivo_de_la_Reforma_Educativa.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Monroy Segundo, R.; Garduño Nava, V.; Cruz Albarrán, O.R.; Ramírez Pérez, C. Retos de los Docentes Formadores de las Escuelas Normales ante la Implementación de la Nueva Escuela Mexicana. Rev. RELEP 2024, 6, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura Álvarez, F. Las implicaciones de la Nueva Escuela Mexicana en el proceso pedagógico. Rev. Bol. Redipe 2023, 12, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiburcio Esteban, C.; Jiménez Lobatos, V.D. Concepciones docentes sobre la interculturalidad en la Nueva Escuela Mexicana. Rev. EntreRios 2020, 3, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J. Reacciones a la Presentación de Nuevo Modelo Educativo. Once Noticias. 16 August 2022. Available online: https://oncenoticias.digital/nacional/en-que-consiste-el-nuevo-plan-de-estudios-para-preescolar-primaria-y-secundaria/151905 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Blancas Madrigal, D. Basan Diseño de los Libros de Texto Gratuitos en Plan de Estudios “Patito”. Crónica. 14 August 2023. Available online: https://www.cronica.com.mx/nacional/basan-diseno-libros-texto-gratuitos-plan-estudios-patito.html (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Fernández, M.A.; Reyes, S.; Herrera, L. Marco Curricular General 2022: Una Oportunidad Perdida Para la Educación Básica. Nexos. 24 August 2022. Available online: https://educacion.nexos.com.mx/marco-curricular-general-2022-una-oportunidad-perdida-para-la-educacion-basica (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Andere, E.; Villalpando, I. Errores y Enredos de la Reforma Educativa y los Libros de Texto Gratuitos. Nexos. 17 May 2013. Available online: https://educacion.nexos.com.mx/errores-y-enredos-de-la-reforma-educativa-y-los-libros-de-texto-gratuitos (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Jarquín Ramírez, M. Batalla Curricular en la Nueva Escuela Mexicana: Alcances y Límites del Equilibrismo Progresista. Perspectivas. 10 October 2022. Available online: https://revistacomun.com/blog/batalla-curricular-en-la-nueva-escuela-mexicana-alcances-y-limites-del-equilibrismo-progresista (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Villa Román, E. La Polémica por los Nuevos Libros de Texto de la SEP Marca el Arranque del Nuevo Ciclo Escolar en México. El País. 28 August 2023. Available online: https://elpais.com/mexico/2023-08-28/la-polemica-por-los-nuevos-libros-de-texto-de-la-sep-marca-el-arranque-del-nuevo-ciclo-escolar-en-mexico.html (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Carmona Álvarez, C. ¿Quemar Los Libros de Texto Gratuitos? Milenio. 7 August 2023. Available online: https://www.milenio.com/opinion/cuauhtemoc-carmona-alvarez/agora/quemar-los-libros-de-texto-gratuitos (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Pérez Mendoza, A.P.; Soto Castillo, J.; Martínez Alcalá, G.; Juárez Vázquez, M.A. Desafíos de los Docentes Normalistas con la Implementación de la Nueva Escuela Mexicana. Rev. RELEP–Educ. Pedag. Lat. 2024, 6, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, N. The Multiple Meanings of “Student-Centred” or “Learner-Centred” Education, and the Case for a More Flexible Approach to Defining It. Comp. Educ. 2021, 57, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweisfurth, M. Learner-Centred Education in International Perspective: Whose Pedagogy for Whose Development? Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S.; Walsh, D.J. Unpacking child-centredness: A history of meanings. J. Curric. Stud. 2000, 32, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.M.; Schweisfurth, M. Constructivism and learner-centeredness in comparative and international education: Where theories meet practice. In Theory in Comparative and International Education; Jules, T.D., Shields, R., Thomas, A.M., Eds.; Bloomsbury Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, G. Foundations of Classroom Change in Developing Countries, Part 1: Evidence. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349094827_Guthrie_FOUNDATIONS_OF_CLASSROOM_CHANGE_IN_DEVELOPING_COUNTRIES_Vol1_Evidence_2021 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Sakata, N.; Bremner, N.; Cameron, L. A Systematic Review of the Implementation of Learner-Centered Pedagogy in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Rev. Educ. 2022, 10, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, N.; Sakata, N.; Cameron, L. The Outcomes of Learner-Centred Pedagogy: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2022, 94, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.M. Beyond the polarization of pedagogy: Models of classroom practice in Tanzanian primary schools. Comp. Educ. 2007, 43, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, G. Understanding Teacher Reactions to Curriculum Reforms: A Comprehensive Typology. Glob. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2023, 23, 17–35. Available online: https://socialscienceresearch.org/index.php/GJHSS/article/view/103818 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Bremner, N. From Learner-Centred to Learning-Centred: Becoming a “Hybrid” Practitioner. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 97, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, M.C. The Reconceptualization of Learner-Centred Approaches: A Namibian Case Study. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2004, 24, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavrus, F.K. The cultural politics of constructivist pedagogies: Teacher education reform in the United Republic of Tanzania. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2009, 29, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. The New Meaning of Educational Change, 5th ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, J.P.; Reiser, R.A.; Reimer, T.R. Policy Implementation and Cognition: Reframing and Refocusing Implementation Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2002, 72, 387–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, M. Complexity and Policy Implementation: Challenges and Opportunities for the Field. In New Directions in Education Policy Implementation: Confronting Complexity; Honig, M., Ed.; The State University of New York: Albany, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S. Cambodian Teachers’ Responses to Child-Centered Instructional Policies: A Mismatch Between Beliefs and Practices. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 50, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedell, M. Planning Educational Change: Putting People and Their Contexts First; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann, S. Teachers’ beliefs and educational reform in India: From “learner-centred” to “learning-centred” education. Comp. Educ. 2019, 55, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ma, X. Education for learner-centredness in Chinese pre-service teacher education. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2009, 3, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akello, L.D.; Timmerman, G. Local language a medium of instruction: Challenges and way forward. Educ. Action Res. 2018, 26, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaobing, T.; Adamson, B. Student-Centredness in Urban Schools in China. London Rev. Educ. 2014, 12, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, M.; Koya Vaka’uta, C.F.; Lagi, R.; McGrath, S.; Thaman, K.H.; Waqailiti, L. Quality education and the role of the teacher in Fiji: Mobilising global and local values. Compare 2017, 47, 872–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]