Abstract

This mixed research aimed to determine if, in their initial training, teaching students consider Scratch and Storybird, digital storytelling applications, as contributing to promoting originality after an intervention in which they previously experimented with them. It was studied whether they considered it convenient to encourage children’s creativity by combining them to create stories in Spanish and English (as EFL) and then having the teacher adapt these two applications. The participants included 134 university students, teachers in initial training at Huelva’s Campus in Spain. The quantitative results as a whole showed significant differences regarding the different dimensions of originality analysed. In the qualitative ones, it was recognised that these apps encourage cognitive development, creativity, learning, communicative competence, and learning attitude, recognising the apps as didactic tools. When cross-examining the data, it was deduced that the digital storytelling applications preferably provide the benefits of encouraging, in a specific way, originality, imagination, and the production of stories in a multimodal manner. Thus, the emerging variables are cognitive.

1. Introduction

Creativity is a concept that has been extensively studied, although there is a relative lack of research focusing on its subcomponents. This particular study specifically explored one of its constituents: originality. A mixed-methods study was conducted to investigate how the sample perceived the variable of originality in relation to two language-learning applications that employ stories, namely, Storybird and Scratch.

Employing a mixed-methods approach, this study aimed to delve deeper into this phenomenon, aiming to provide data that can serve as a foundation for subsequent studies in the field of digital storytelling with applications (DTS). This field is undergoing scientific expansion due to the technological era, and the study also examined its impact on training in digital competence, particularly in the initial training of teachers.

2. Literature Review

There are different meanings associated with the creativity construct. According to Walia [1], the previous literature has intertwined the concepts of creation and creativity. Consequently, scholars have not given sufficient attention to the active process of the creative act that may end in creation or not.

Neuroscience has revealed that creativity is a complex process involving the intervention of various brain areas [2]. Additionally, there are various variables within this process, with the dimension of originality being one of its components. Weisberg et al. [3] align with Walia [1] in suggesting that the diverse conceptions of creativity have been founded on models of creativity built on logical and semantic argumentation. Weisberg et al. [3] verified this generally, emphasising the importance of novelty and intentionality in creativity judgments.

Humphrey [4] and Mendoza [5] asserted that mental capacity has predominantly been approached from an individualist and cognitivist point of view.

Moreover, the neuroscience research of Stephens et al. [6] revealed that when someone sees or listens to a story, the neurons in the brain are activated with the same patterns as those of the speaker. This process is referred to as neural coupling or mirroring, occurring in different parts of the brain. It facilitates the sharing of a contextual model of the situation, involving the frontal, motor, and sensorial cortices in the process of creating and understanding stories. The brain anticipates the story´s resolution with dopamine, aiding in the precise memory of certain details. Regarding the cultural impact of storytelling, Boris [7] added the following:

storytelling forges connections among people, and between people and ideas. Stories convey the culture. When it comes to our countries, our communities, and our families, we understand intuitively that the stories we hold in common are an important part of the ties that bind.(p. 1)

Furthermore, Shao et al. [8] explained that creativity is a complex and culture-sensitive concept, with differences observed between Eastern and Western cultures. Firstly, they possess dissimilar implicit and/or explicit conceptions of creativity. Secondly, individuals from individualist and collectivist cultures show variances in their preferred creative procedures and creative processing modes.

However, another more social and cultural perspective reveals the role of the mind in people’s interactions, suggesting that intellect is a collective occurrence within interactions. Perhaps this model is more suitable for understanding the co-creation of stories and how DTS conditions this process, as the cognitive processes targeted by these apps are organised with respect to the functions for storytelling.

Vygotsky [9] underscored the correlation between imagination and creativity in childhood. Navarro et al. [10] and Kozbelt et al. [11] supported the idea that creativity unfolds over time, influenced by social interaction and the environment. Weinstein and Preiss [12] concluded that working on students’ thinking skills through the use of a scaffolding technique increased their confidence and autonomy of thought.

Kampylis et al. [13] presented a study on first-year education students using the Teachers’ Conceptions of Creativity Questionnaire (TCCQ). They emphasised that creativity is a crucial element for individual and social development. In addition, the authors conducted a comprehensive review of earlier studies by other researchers on the perception of creativity. Cachia and Ferrari [14] conducted a comprehensive study on creativity in European ICT teachers. According to the findings, creativity seems to be the ability to create an original product.

2.1. Creation of Original Stories

Pavlik [15] demonstrated in her research on structural imagination that inventive thought is governed by abstract apprehension and constructions. She concluded that representational knowledge influences the meaning and originality of the story. Thus, significant and innovative stories seem to enhance nonfigurative insights more than those that do not. Furthermore, significant correlations were established between creating meaningful vs. nonmeaningful narratives and using meaningful vs. nonmeaningful knowledge sets.

Csikszentmihalyi and Getzels [16] found a positive interaction between discovery-oriented behaviour in the creative problem origination phase and the originality of the creative product but not the craft. According to Sap et al. [17], based on neurolinguistics programming, imaginary stories have an essentially more linear storyline flow than remembered narratives, in which contiguous enunciations are more detached. If possible, remembered stories depend on more on first-person facts founded on episodic memory, just as illusory narratives bring to light more common-sense knowledge based on semantic memory.

Antonsen [18] stated that in interactive works of fiction, such as video games, journey books, and role-playing games, consumers acquire the point of view and the role of the protagonist and immerse themselves in the story. Furthermore, they require imagining themselves to be another person and imagining parts of the story while keeping in mind that they are located in the projected place. Larsen [19] researched divergent thinking, concluding that children produce original ideas after time off-task.

Weisberg [20] studied problem solving along with intuition or revelation. The participation of the memory in the aid of intuition to solve a problem depends on the specific problem. Steffensen and Vallée Tourangeau [21] stated that the problem of intuition is also believed to undergo different phases. More of these phases would depend more on working memory. Vallée Tourangeau and Vallée Tourangeau [22] explained that problem solving is part of higher cognition: thought uses communicating procedures based on a widespread assortment of external stratagems covering multiple time scales. For this reason, they recommended adopting an interactivist perspective to describe how these stratagems are dynamically shaped in time and space.

2.2. Digital Storytelling (DST)

Djonov et al. [23] studied the use of digital multimedia formats combined with analogue materials, revealing that preschool-age children are aware of the possibilities of the media and the semantic models in the narrative shown transmedially. Simultaneously, older children demonstrate a comprehension of story procedures and the ability to construct various social issues by choosing the most suitable semiotic stratagems accessible in the selected media. Therefore, LEGO animation, comic strips, as well as programs like Stop Motion or Garageband can assist in establishing a toddler’s multimedia authorship. There are DST-type apps that are applied to language or teaching other disciplines, such as the one proposed by Dietz et al. [24] called StoryCoder: an application designed to teach computational thinking notions via storytelling in a voice-guided application for infants.

The validated test by Moral et al. [25] considers six aspects of the creativity potential of video game apps: flexibility, originality, fluidity, problem solving, product development, and, finally, copublishing and dissemination capacity. According to the study by Del Moral et al. [26], (DST) is an inventive story exercise based on the construction of multimodal narratives, with the feeling of emotion through colour [27]. This approach promotes both communicative [28] and digital skills.

Yoon [29] discovered positive attitude changes in second language (L2) learning with a deeper understanding of the content and greater participation. Digital storytelling engaged learners in the story´s content, fostering motivation, interest, and confidence to learn another language. Ya-Ting and Wan-Chi [30] concluded that DST increased students’ understanding of the content to be studied, their willingness to inquire, and their ability to reflect critically. However, Hava [31] did not emphasise motivation. Additionally, there were improvements in self-confidence and students´ subjective use after the storytelling activity, demonstrating DST as a suitable tool for learning environments to develop linguistic and digital competence.

Liu et al. [32] conducted a study with DTS in primary education. Two digital storytelling performance indicators, stages of language usage and planes of inventiveness, were established to have noteworthy but diverse influences on language learning. On the one hand, learners’ achievement in the use of language in digital storytelling was significantly associated with their performance. In contrast, creativity performance was meaningfully linked to numerous elements of motivation: elaboration, task value, and extrinsic motivation. Additionally, the proposed method had a positive effect on schoolchildren’s linguistic performance, contributing to increasing student motivation in two ways: orientation and extrinsic goal setting.

Liang [33] suggested multimodal narrative discourse analysis (MNDA) with allied pedagogic and investigative means to instruct and inquire into narrative. The intervention demonstrated appropriate practice of story elements, discursive arrangements, and formal strategies, as well as the physical, visual, and video resources used. All these elements helped learners develop multimodal designs and narrative styles.

Pereira and Campos [34], in terms of empathy framed in the pedagogy of multiliteracies, focus more on cognitive abilities. They investigated a case focusing on an animated narrative with hybrid multimodal text. Through the narrative on a public digital platform, students learned about refugees. The participants positioned themselves in three very different positions: as detached viewers of the characters embodied, as observers of the distress of others, or as social performers. Lawrence and Mathis [35] designed an intervention to assess learners multimodally by asking them to create multimodal portfolios. Four at-risk students were observed and interviewed, and their artifacts were evaluated. It was concluded that they were meaning generators capable of critical participation in multimodal thinking and communication.

According to Ivone [36], digital tools can greatly facilitate the process of story creation by students. Many dimensions are enhanced, including originality. She highlighted several tools, including Storybird, which allow the creation of different formats. Families can also be involved in the process. Most importantly, it allows for more autonomous creation, whereas Scratch may require more assistance.

Del Moral et al. [37] analysed a sample of 20 apps of various kinds, including Storybird, using the quantitative questionnaire CREAPP K6-12,. The results regarding originality were significant from the bottom up in terms of favouring the representation of unpublished facts in the stories, encouraging curiosity and inquiry, and involving the customer in the construction of emotional plots.

The Storybird app offers default images and the ability to add text, allowing users to create stories with multimodal quality in an original way. The Scratch app is a bit more complex to use, allowing texts, predetermined images, as well as the movement of the characters. Both apps are used for language learning for children and can be useful for other educational levels, such as immigrant adults at risk in Spain who know Spanish.

To design this study, the following research questions were previously formulated:

- RQ1. Is there a relationship between the dimensions of originality?

- RQ2. Do students positively evaluate the applications aimed at developing these dimensions?

- RQ3. Are there sex differences when students weigh the dimensions of originality?

- RQ4. Do students find that children’s creativity is encouraged by creating stories and then having a teacher adapt them to Scratch and Storybird?

3. Materials and Methods

The research methodology was mixed for a quasi-experimental inquiry. When both types of methodologies are combined, a broad knowledge of the phenomena becomes possible [38]. The data collected were of different nature, yet they complemented each other by providing diverse perspectives on the study object. Additionally, the data could finally be triangulated.

The quantitative methodology aligns with positivism. Its objective is “to test (confirm or falsify) hypotheses based on certain indicators of the variables” [39] (p. 67). Therefore, the aim is to gather quantifiable and statistically measurable data on a proposed variable.

Statistical descriptive analysis was conducted, using bar charts to visualise frequencies. Furthermore, inferential analysis was performed, involving hypothesis testing. This approach helps determine if there is enough evidence in a sample to reject a specific statement about the population in general. Significance, in this test, pertains to the statistical importance of the results. Additionally, Spearman’s test was employed to identify correlations. Statistical significance indicates whether the test results are robust enough to suggest that the observed relationship in the sample also exists in the broader population.

The qualitative methodology is rooted in constructivism and phenomenology, responding to an epistemic reality approach where knowledge depends on individual´s position in the context. This method aims to deepen the perceptions of the participants by posing broad questions that collect a wealth of both expected and unexpected variables [40].

3.1. Hypotheses

In this research, we formulated hypotheses based on RQ1 to 3. These hypotheses were tested using statistical tests of hypothesis contrast, chi-square and Spearman. We examined their acceptance or rejection is considering the variables mentioned above:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

There is a relationship between the dimensions of originality.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The apps used to develop the dimensions of originality are positively rated by students.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

There are sex differences in the rating of the dimensions of originality.

Simultaneously, and in consideration of the fourth research question, this study also explored whether the sample acknowledged that creating stories and then adapting them to storytelling apps enhances creativity. To complement this, an open-ended qualitative question was posed to the sample: Why do you believe it is useful (or not) to encourage children’s creativity by combining these tools for creating stories and then having the teacher adapt them to Scratch and Storybird?

3.2. Participants

The participant sample consist of two groups of Spanish first-year students during the 2021–2022 academic year at the University of Huelva in the Andalusian autonomous region of Spain. This region, located in the south, is the largest one in Spain. The socioeconomic level of the students is medium to even medium-low. Those studying at the Huelva campus come from the province of Huelva and other nearby neighbouring provinces, including Seville, Caceres, and Cadiz.

For this academic year, the student population of teachers in initial training comprised 272 students, randomly grouped through simple random convenience sampling (SAS).The external validity of these results was not studied, and the total sample size was 134 participants.

The mean age of the sample was 20.20 years, with a standard deviation of 1.50. Despite a range in ages from 19 to 30 years, 91% of the sample fell within the 19–21 age range, indicating a fair degree of consistency. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the sample was predominantly female (n1 = 113), not male (n2 = 21).

3.3. Design, Procedure, and Instruments

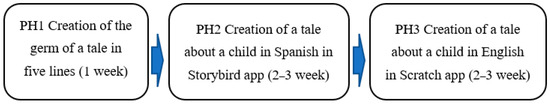

The research design was developed as follows: Initially, a teaching intervention occurred, during which university students from the two groups actively engaged in storytelling in both Spanish and English. Subsequently, they participated in the transmedia creation process using two different apps. In teams, the university students first crafted a short original story in Spanish, focusing on a child protagonist. They then conceptualised a second story in English (as English as a foreign language (EFL)) based on the initial story. In this second story, they aged the protagonist by 10 years, simulating the preparation of an activity aimed at developing the sense of time in children at the primary education level. To bring their stories to life, the first story was visually realised using the Storybird app in Spanish, while the second story was implemented with the multimodal Scratch app in English. The various phases of this intervention are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Intervention phases.

The applications were chosen based on the advance characteristics they offer. Storybird is an AI-powered tool that enables users to create personalised stories for children. The platform provides a library of pre-existing stories, a tool to create and download custom stories, and a plugin that enables users to interact with characters from selected stories. The AI analyses and understands the style and structure of stories, enabling scholars to enhance their writing and make it more stylish. Additionally, Storybird facilitates the creation of stories using predesigned templates, collaborative story building, and the option to share work online or keep it private.

Scratch is a visual programming language that allows users to create interactive applications, stories, animations, and games using blocks of code. The platform hosts all the necessary resources and the development environment. Scratch makes it possible to create stories, animations, and games in an entertaining and visual manner. It is recommended for use by children between 8 and 16 years old.

These two applications were chosen because of their homogeneity in the functions they offer. This approach allowed university students to engage in storytelling creation, understand their functionalities, and explore the practical possibilities offered by these two apps.

The data collection phase was designed to gather mixed data through an individual test and a focus group. Participants voluntarily responded to the test, and all the data were collected anonymously. The research questions and inquiry tools are detailed in Table 1. The focus group was organized in teams of 6 to 8 participants. The test comprised, firstly, 8 closed questions derived from the quantitative questionnaire validated by Del Moral et al. [25], specifically addressing originality component. This test, known as CREAPP K6-12, serves to evaluate the creative potential of playful apps designed for digital storytelling (DST). A cut-off value of 2.5 is considered normal, with “nothing” (1) and “little” (2) having negative connotations while “good” (3) and “a lot” (4) are considered positive answers. Secondly, a broader qualitative aspect was incorporated through an open question about creativity, explored via participation in discussion groups [41] and documented collectively in a group portfolio.

Table 1.

Research questions and research tools used.

Shortly after experimenting with the apps, the students completed the Qualtrics-based questionnaire. The quantitative data of the sample were collected using this tool, wherein university students answered 8 questions based on the questionnaire validated by Del Moral et al. [25].

They responded to the test questions related to the originality component by choosing an answer. Additionally, the teams convened, and a discussion group was held with an open question, with the answers documented in a group portfolio, which was uploaded shortly after to Moodle, a free and open-source learning management system. This open question asked about creativity, a concept encompassing originality and its subcomponents as formulated in the quantitative questions. It was precisely formulated to explore variables that could qualitatively reflect the students’ creativity, originality, imagination, etc.

The data processing phase relied on computer programs, as described in Table 2. Quantitative data were exported to the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 25) IBM´s software for descriptive statistics as well as inferential statistics, including hypothesis testing and chi-square test to compare frequency distributions. Spearman’s statistical correlation test was also conducted to determine the existence of a correspondence between different variables. The contrasting data for hypothesis confirmation were also considered [42].

Table 2.

Data processing and software.

Qualitative data were initially processed through manual analysis, extracting components and subcomponents considering the field and concepts of the didactics of language and in the literature. Subsequently, the text was processed using QDA Miner 4.1. by Provalis Research, a program for category nesting that also determines the quantitative frequency of the subcomponents. Finally, once the quantitative and qualitative data were processed, the triangulation of the two types of data was performed to ensure the richness of the perspectives from different study participants and to verify common variables.

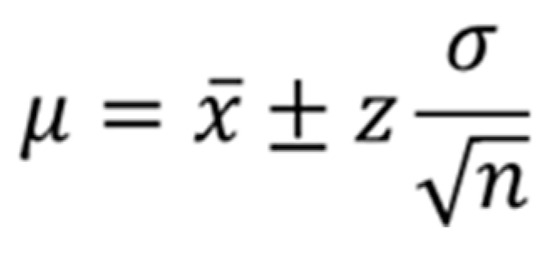

Concerning hypothesis testing, a one-sided comparison of proportions was conducted based on a sample of more than 30 individuals (n = 134); therefore, the normality hypothesis was applied. The formula serves for calculating a confidence interval for the population mean (μ) based on a sample mean (), a critical value (z), and the standard deviation (σ) divided by the square root of the sample size (n). Figure 2 displays the formula.

Figure 2.

Hypotheses testing formula.

The process for hypothesis testing involves the following steps: H0: Null hypothesis, H1: Alternative hypothesis, p: p-value, α: Significance level, and Decision rule: Reject H0 if p < α.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results

The quantitative results are presented from the CREAPP K6-12 test. The questionnaire consisted of an introductory question: 1. Do you think that these two apps, Scratch and Storybird, promote the aspects of the dimension of originality, one of the components of creativity? Subsequently, participants were presented with each of these aspects for response. The quantitative data are presented in the order in which the questions were administered.

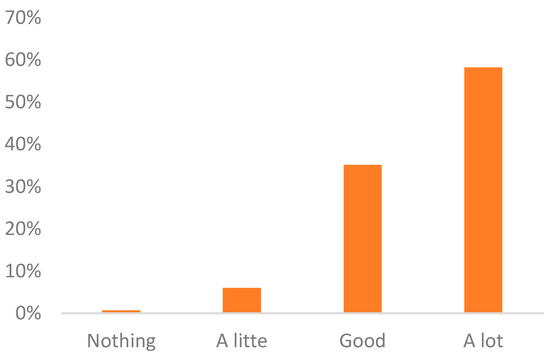

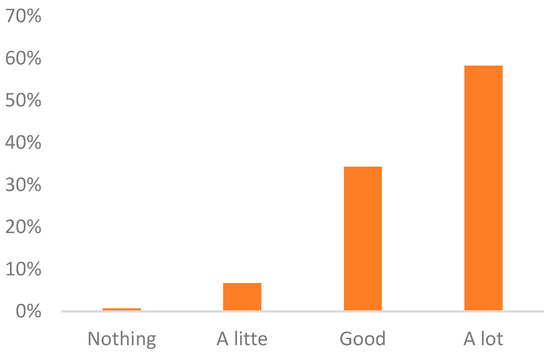

Figure 3 illustrates students’ responses regarding their opinions on the curiosity or inquiry generated by the applications they used. The responses were categorized as “a lot of” (58.2%) and “good” (35.1%), totalling a favourable relative percentage of 93.3% concerning the ability of these apps and the stories composed in them to stimulate curiosity and inquiry. This cognitive quality remotely encourages critical thinking. Fewer responses were categorised as “little” (6%); “nothing” had a negligible representation (0.7%) amongst the responses.

Figure 3.

Dimension regarding arousing curiosity and inquiry.

The average value of the result was 3.5, with a standard deviation of 0.64 used for the dispersion calculation, which was compared to the normal value of 2.5 through a mean contrast. The result of the contrast was 2.65. Therefore, with a confidence level (probabilistic) of 0.95, there was sufficient evidence to assert that P (curiosity–inquiry) was greater than 2.5. In other words, it was positively estimated that apps enhance the curiosity and inquiry of the students.

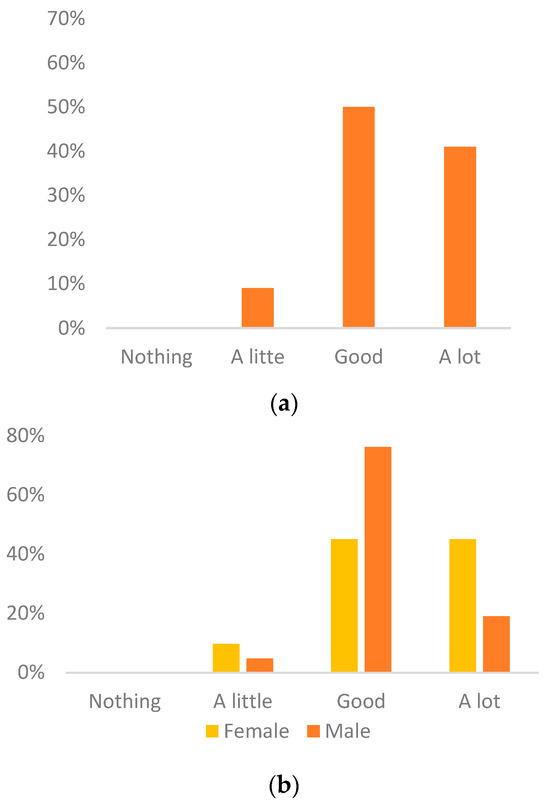

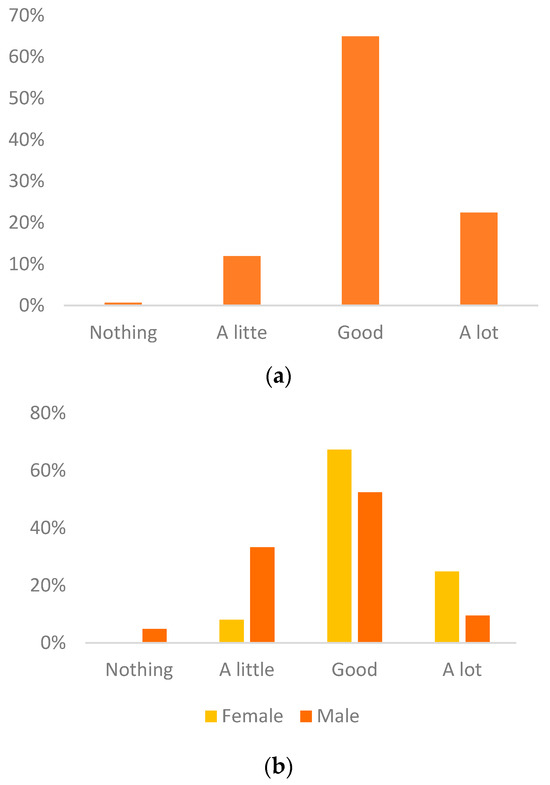

Figure 4a presents the distribution of the resources in the apps used in the research. The results showed 41% for “a lot” and 50% for “good”, totalling a positive response of 91% in two multimodal features: visuospatial and sound elements. The proportion of those responding with “little” was lower (9%). The mean value of the result was 3.2. The standard deviation was 0.63. The result of the contrast was 2.58. Therefore, with a probabilistic confidence level of 0.95, there was sufficient evidence to confirm that P (presentation of resources) was greater than 2.5. Thus, it was found that apps significantly increased the presentation of resources.

Figure 4.

(a) Dimension of presentation of resources. (b) Dimension of presentation according to sex.

In terms of sex, Figure 4b also shows significant differences. Almost half of the women believed that the applications they used either strongly or moderately encouraged the presentation of resources. In contrast, the majority of men (three-quarters) rated this as moderate. This difference was confirmed by a chi-square value of 6.841 and a p-value of 0.33.

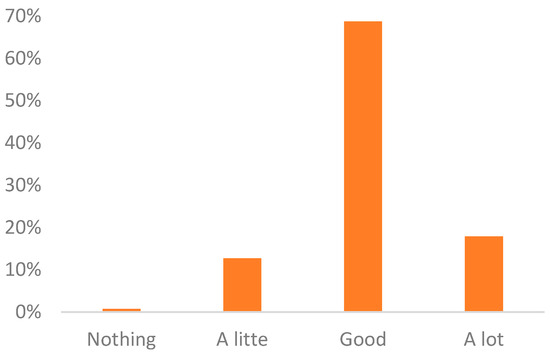

Figure 5 shows that when we combines the responses of “a lot” (58.2%) and “good” (34.3%), the result was positive and significant (92.5%) regarding the activation of the imagination by the unique design elements within these apps. Negative responses were minimal: “little” at 6.7% and “nothing” at 0.7%. Together, they totalled 7.4%. The mean value of the result was 3.4, with standard deviation of 0.65. The critical value was 2.59, indicating significant differences. It can be said that the applications used stimulate the imagination to create their own elements.

Figure 5.

Response to question that apps activate the imagination to design their own elements.

The results, depicted in Figure 6a, significantly favoured the representation of unprecedented facts, with 22.4% indicating “a lot”, and 64.9% indicating “good”. This means that 87.3% of the sample expressed a positive view. Regarding the negative responses, “little” accounted for 11.9% and “nothing” for 0.7% of the responses. In contrast, both negative positions constituted 12.6% of the responses. The mean value of the result was 3, with standard deviation of 0.6 and a critical value of 2.58. Thus, significant differences were evident, and it can be said that the apps promote the representation of unprecedented fact.

Figure 6.

(a) Dimension of encouraging the representation of unprecedent facts. (b) Dimension of encouraging the representation of unprecedent facts according to sex.

Differences also arose when considering sex, as illustrated in Figure 6b. Approximately a quarter of women thought that the apps strongly encouraged the presentation of unprecedented fact, while two-thirds thought that they encouraged it moderately. Men’s responses were distributed between strong encouragement (about a half) and mild encouragement (a third). A highly significant difference between the sexes was observed, with a chi-squared value of 17.370 and a p-value < 0.01.

The results, depicted in Figure 7, show that respondents significantly favoured the idea that the two apps offer open responses that diverge from the action–reaction principle. Approximately 17.9% rated this dimension as “a lot” and 68.7% as “good”, resulting in a total favourable response of 86.6%. On the contrary, 12.7% responded with “little” and 0.7% with “nothing”, totalling 13.4%. The mean result value was 3, with standard deviation of 0.57. Given that the critical value is 2.58, significant differences were noted, indicating that the applications offer open-ended responses distinct from the action–reaction principle.

Figure 7.

Dimension of offering open answers far from the action–reaction principle.

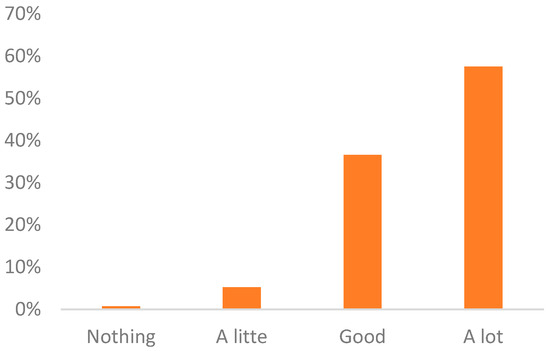

Figure 8 illustrates that 94.1% of the sample responded favourably regarding whether the app provides elaboration of novel proposals, with 57.5% responding with “a lot” and 36.6% responding with “good”. A negative view is held by 5.9% of the sample (5.2% responding with “little” and 0.7% with “nothing”). The mean result was 3.5, with a standard deviation of 0.63. The critical value, 2.58, confirmed the presence of significant differences in this dimension as well and indicates that these applications promote the development of novel proposals.

Figure 8.

Dimension of the app favouring the elaboration of novel proposals.

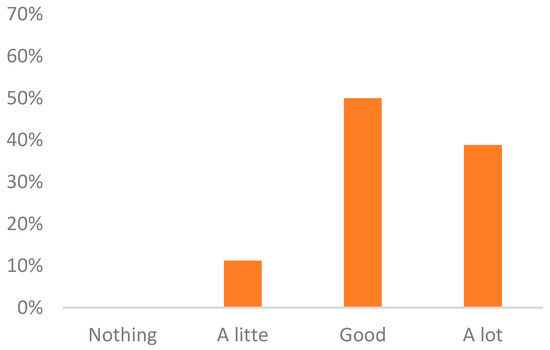

A significantly favourable response of 88.8% (38.8% expressing “a lot” and 50% “good”) is highlighted in Figure 9 regarding the promotion of the construction of emotional plots. Only 11.2% responded with “little” regarding this dimension. The mean result value of the result was 3.3, with a standard deviation of 0.65. The critical value was 2.59. It is argued that apps promote the construction of emotional plots.

Figure 9.

Dimension of apps promoting the construction of emotional plots.

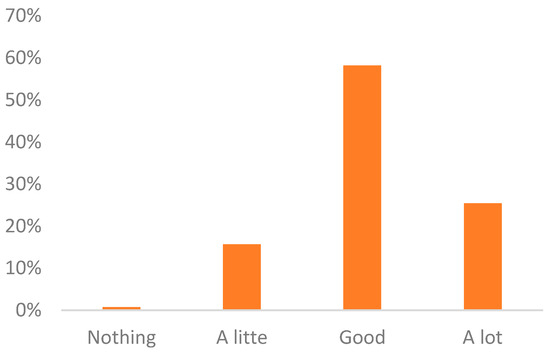

The respondents, as depicted in Figure 10, favoured the frame resolution of the apps, with 77.6% providing a positive response (52.2% “good” and 25.4% “a lot”). A negative response was noted in the minority of respondents (15.7% responding with “little” and 0.7% responding with “nothing”). The mean value of the results was 3.6, with a standard deviation of 0.65. The critical value was 2.59. Therefore, significant differences were also observed in this dimension. It can be said that the apps used in this research promote the resolution of plots in an unexpected way.

Figure 10.

Dimension of the apps encouraging resolution of plots in unexpected ways.

It was demonstrated earlier that all eight dimensions constituting originality contributed significantly to its enhancement. Table 3 clearly indicates a robust correlation among all these dimensions. In every instance, a highly significant correlation was observed, with a p-value below 0.01. Consequently, all dimensions contributed equally to the enhancement in originality.

Table 3.

Spearman correlation of the dimensions that make up originality.

4.2. Qualitative Results

In this section, the qualitative results are presented, including the frequency of the appearance of the subcomponents. The qualitative question posed was as follows: Why do you think it is convenient to encourage the creativity (or not) of children to create stories and then the teacher adapting them to Scratch and Storybird? The qualitative results from this question are provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Convenience of fostering creativity by combining storytelling creation and adaptation to Scratch and Storybird.

Thus, six components emerged regarding these apps. These apps were recognized for encouraging cognitive development, creativity, learning, and communicative competence; they serve as didactic tools that improve learning attitudes.

Indeed, it was emphasized that the apps promote cognitive development, with creativity being a prominent component of this development. However, we highlight creativity as a component due to its significance in the perception of this sample, as well as in response to the initial question and the interest in identifying the emerging subcomponents. Concerning cognitive development, five elements emerged: imagination, reflective capacity, memory, intellectual autonomy, and creativity. Regarding creativity, six subcomponents arose, with the most frequently studied and acknowledged being originality. Additionally, the other related factors followed in descending order: problem solving, product development, flexibility, fluidity, and diffusion.

In relation to the encouragement of learning, two subcomponents emerged: content learning and the aesthetics of the stories. Concerning the component of communicative competence, six subcomponents arose, namely, communicative competence correlated with originality and creativity, multimodal expression, expressive correction, freedom of expression, reading comprehension, and oral competence. The two apps were attributed three qualities. They were appreciated as playful, innovative teaching tools that can be seamlessly combined with analogue tools. Lastly, participants considered that the apps improve five aspects: motivation, self-esteem, curiosity, attention, and interest.

5. Discussion

5.1. Deliberation

Based on the data collected in this research, the significance of utilizing technology to enhance learning is evident, aligning with the findings of Kocam-Karoglu [28]. This observation is consistent with those of Zare et al. [43], who discovered that storytelling can foster deep learning and stimulate critical thinking. Yoon [29] similarly identified that storytelling can lead to the deepening of understanding. In this specific instance, the promotion of originality, a component integral to the concept of creativity, was achieved through the use of two digital storytelling applications, Scratch and Storybird, both of which were consistently rated positively, as a broad assertion.

The students highly rated all eight dimensions of originality that were analysed. In every case, the results indicated the proficiency of the apps and underscored the significance of originality as a crucial element in crafting narratives. Consequently, hypothesis H2 was supported with a confidence level of 95%, showing that the applications employed for developing the dimensions of originality received positive evaluations from the students. In this context, our findings align with the findings of Cater et al. [44], who established a moderate correlation among satisfaction–experience–narrative purpose. Additionally, Dessart and Pissarti [45] asserted that storytelling content positively influences consumer engagement, which can be transferred to engagement in learning.

Several studies have corroborated that digital applications foster originality in students of various age groups [31,36,40]. The understanding of the qualities explored by other researchers, such as curiosity–inquiry [46], resourcefulness [47], imagination [48], representation of unprecedented facts [49], open-ended responses [28], innovative proposals [50], constructive plots [51], as well as plot resolution frameworks [52], is enhanced by our study. Furthermore, a clear relationship existed among these eight dimensions in all cases, supporting hypothesis H1, which posited a relationship between the dimensions of originality. These dimensions demonstrated a close connection, suggesting that DTS promotes an integrated and creative narrative experience.

However, there were no major differences in descriptive and inferential results when considering sex. In only two cases were results significant: women were more likely than men to consider that the apps favour the presentation of character galleries, scenarios, and audio (Figure 4a); women also more positively rated the presentation of unprecedented facts (Figure 6a). These findings are consistent with those of other studies [53], where significant differences were established: girls were more likely to perceive the importance of developing story development skills. Therefore, hypothesis H3, stating that there are sex differences in the evaluation of dimensions of originality, could only be partially supported. These findings answer the third research question (RQ3). Consequently, all alternative hypotheses were supported at the 95% confidence level.

From the qualitative analysis, it is noteworthy that in terms of creativity, the same six subcomponents of the test of Moral et al. [25], which were applied to video games, emerged. These apps also allow for originality, flexibility, fluidity, problem solving, product development, and dissemination. The findings for the categories of originality, flexibility, and storytelling articulateness, involved in storytelling practices, are consistent with those of previous research by Webb and Rule [54]. Likewise, these are two apps perceived as complete multimodal didactic tools [28] for teaching lessons, affecting 26 variables, some of them novel. In this way, the original set of research questions was answered. First, codes of conceptual knowledge (knowing what) emerged, highlighting the frequency of learning new content [30] and its necessity for progression in life, both socially and personally [13].

Second, the procedural knowledge (know-how) subcomponents emerged, highlighting the invention and production of original stories [15,37], in which multimodal expression is facilitated [23,33]. Imagination, as the quantitative results also showed, [9,37,55]; problem solving [3,20]; and emotional plots [37] were emphasised. Autonomy of thought and mental capacity, in general, appeared to be of a lesser degree of importance here [12]. These two variables align with Djonov’s [56] estimate that the child is capable of becoming a multimodal author, even with transmedia formats.

Third, unlike Hava’s [31] study, attitudinal knowledge (knowing how to be) was identified by recognising the motivation it generates [29,32]. Likewise, memory emerged as an important variable [6,17,20,21], and self-esteem s correlated with confidence [31]. With these variables obtained from the qualitative answers, as shown in in Table 4, the fourth research question (RQ4) was answered.

Our results align with the qualitative results of a previous investigation by Del Moral et al. [37], recognising the development of expression and communication through the use of DTS, as well as that of digital competence, though less explicitly. In this study, the variables of the character’s point of view, empathy with the character [56], or self-localization [18] did not appear, although mental flexibility did. The variables time and space did not appear explicitly either [22].

Digital storytelling apps offer a wide range of tools and resources for creating unique and original stories. From creating custom characters and scenarios to incorporating visual effects and sound, these apps inspire users to think outside the box and explore their creativity to its fullest.

The study found that DTS provides the benefit of encouraging originality in a special way. This conclusion is consistent with the results of both Cachia and Ferrari [14] and Csikszentmihalyi and Getzels [16] in a context that contemplated the use of ICT. In this study, imagination and the production of stories in a multimodal version were significant.

Similarly, the multimodal nature of the apps stood out, providing resources such as the creation of characters, scenarios, and audio, as well as the possibility of exploring different resolutions [6]. This makes it possible to develop surprising plots in terms of quantity and to tackle problems in terms of quality, encouraging originality and creativity in digital storytelling, both in terms of plot development and story depth [54].

In conclusion, this study differs from other studies by demonstrating the relationship between the eight dimensions of originality as facilitated by the apps. This result answers the first research question (RQ1) and establishes the positive perception regarding all these dimensions of the sample, which was determined using a quantitative method, in line with the findings of other studies. This contribution answers the second research question (RQ2). This study provides four common (triangulated) variables. Therefore, the original four research questions were answered as described in this section.

Equally, this research provides a global and rich vision of the benefits of these applications for learning language, considering the mixed technique, in line with Holmes et al. [55], who found that there is a positive relationship between creativity through storytelling playing and language abilities through observation research.

Therefore, it is emphasised that storytelling apps promote four cognitive variables (originality, imagination, production, and resolution), aligning with the perspectives of other researchers [34,35].

5.2. Implications for Practice

Due to the details described after the analysis and the multimodality of these two storytelling apps, Scratch and Storybird, recognized by the sample, these apps were found to be suitable for children learning Spanish and English, as well as for immigrant adults at risk in their knowledge of an additional language. Teachers may consider these apps as offering an interactive and engaging way to improve language skills, through stories and multimodal resources, which can help enhance fluency and comprehension in both languages.

It was found that including digital storytelling applications, such as Scratch and Storybird, in educational programming stimulates various dimensions of originality, creativity, and deep learning among learners. These applications facilitate the development of cognitive variables such as originality, imagination, production, and resolution. The relationship between these components is evident, highlighting the positive evaluation of these aspects by undergraduates. The use of these multimodal tools not only enhances language skills but also encourages problem solving, critical thinking and emotional engagement. Overall, the study emphasizes the significant role of technology, specifically digital storytelling apps, in school curricula that contemplate digital competence.

5.3. Future Research

Prospectively, the above-mentioned four emerging variables—originality, imagination, production, and resolution—open numerous avenues for further empirical research and investigation. This is mainly because the use of applications, such as DTS, is increasingly widespread, and these apps are integrated into learning environments at all levels.

Future research could delve deeper into these emerging variables with larger samples. Additionally, researchers could explore whether these emerging variables remain consistent when other storytelling applications are used. Comparative studies among students groups of different nationalities could also be incorporated to achieve results using ANOVA or independent Kruskal–Wallis tests.

5.4. Limitations

The limitation of the study is that the sample could have been much larger. Similarly, in the research design, an experimental study could have been conducted, comparing control and experimental groups with a pretest before the intervention and a post-test to compare the results and study correlations between the components of originality. Another limitation is that a comparative study could have been carried out not only between groups of Spanish students from different universities but even between countries, allowing for a deeper exploration of the cultural variable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, B.P.-A.; methodology, B.P.-A. and Ó.N.-M.; software, B.P.-A. and Ó.N.-M.; formal analysis, B.P.-A. and O.N; investigation, B.P.-A. and Ó.N.-M.; resources, B.P.-A.; data curation, B.P.-A. and Ó.N.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.P.-A. and Ó.N.-M.; writing—review and editing, B.P.-A. and Ó.N.-M.; supervision, B.P.-A. and Ó.N.-M.; project administration, B.P.-A.; funding acquisition, B.P.-A. and Ó.N.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Multiliteracies for Adult At-Risk Learners of Additional Languages (MultiLits) R& D project, Ref. PID2020-113460RB-I00, financed by the (Spanish) Ministry of Innovation and Sciences, State Research Agency MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and according the Institutional Ethics Frame of UNIVERSIDAD DE HUELVA for studies involving humans. It was a noninterventional study: there were no risks associated with it. The participants were fully informed of the reasons for conducting the research and how the information would be used; their anonymity was assured.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Walia, C. A Dynamic Definition of Creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2019, 31, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, D.; Dunson, D.B. Bayesian Inference and Testing of Group Differences in Brain Networks. Bayesian Anal. 2018, 13, 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, R.; Pichot, N.; Bonetto, E.; Pavani, J.B.; Arciszewski, T.; Bonnardel, N. From Explicit to Implicit Theories of Creativity and Back: The Relevance of Naive Criteria in Defining Creativity. J. Creat. Behav. 2021, 55, 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, N. Una Historia de la Mente; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza García, J. Otra idea de mente social. Lenguaje, pensamiento y memoria. Polis 2017, 3, 13–46. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, G.J.; Silbert, L.J.; Hasson, U. Speaker-listener neural coupling underlies successful communication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14425–14430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boris, V. What Makes Storytelling so Effective for Learning. Harvard Business Learning. Available online: https://www.harvardbusiness.org/what-makes-storytelling-so-effective-for-learning/ (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Shao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, J.; Gu, T.; Yuan, Y. How does culture shape creativity? A mini-review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Imagination and Creativity in Childhood. J. Russ. East Eur. Psychol. 2004, 12, 7–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, C.; Mateos, C.; Rodriguez, M. Cultural Scenes, the creative class and development in Spanish municipalities. Eur. Urban Cult. Stud. 2012, 21, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozbelt, A.; Beghetto, R.A.; Runco, M.A. Theories of Creativity. In The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity; Kaufman, J.C., Sternberg, R.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 20–47. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, S.; Preiss, D. Scaffolding to Promote Critical Thinking and Learner Autonomy among Pre-Service Education Students. J. Educ. Train. 2017, 4, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kampylis, P.; Berki, E.; Saariluoma, P. In-service and prospective teachers’ conceptions of creativity. Think. Skills Creat. 2009, 4, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachia, R.; Ferrari, A. Creativity in Schools: A Survey of Teachers in Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlik, L. Structured Imagination in Story Creation. J. Creat. Behav. 1997, 31, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Getzels, J.W. Discovery-Oriented Behavior and the Originality of Creative Products: A Study with Artists. In The Systems Model of Creativity; Csikszentmihalyi, M., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sap, M.; Horvitz, E.; Choi, Y.J.; Smith, N.A.; Pennebaker, J.W. Recollection versus Imagination: Exploring Human Memory and Cognition via Neural Language Models. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 1970–1978. [Google Scholar]

- Antonsen, P.F. Self-Location in Interactive Fiction. Br. J. Aesthet. 2021, 61, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.A. Measuring child-level originality through the strategic use of incubation periods during divergent thinking assessment. Think. Ski. Creat. 2022, 46, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, O.R. Insight, problem solving, and creativity: An integration of findings. In Insight: On the Origins of New Ideas; Vallée Tourangeau, F., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen, S.V.; Vallée Tourangeau, F. An ecological perspective on insight problem solving. In Insight. Sobre el Origen de las Nuevas Ideas; Vallée Tourangeau, F., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 180–199. [Google Scholar]

- Vallée Tourangeau, F.; Vallée Tourangeau, G. Mapping systemic resources in problem solving. New Ideas Psychol. 2020, 59, 100812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djonov, E.; Tseng, C.I.; Lim, F.V. Children’s experiences with a transmedia narrative: Insights for promoting critical multimodal literacy in the digital age. Discourse Context Media 2021, 43, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, G.; Le, J.K.; Tamer, N.; Han, J.; Gweon, H.; Murnane, E.L.; Landay, J.A. StoryCoder: Teaching Computational Thinking Concepts through Storytelling in a Voice-Guided App for Children. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Online, 8–13 May 2021; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Del Moral Pérez, M.E.; Bellver, M.C.; Guzmán, A.P. CREAPP K6-12: Instrumento para evaluar la potencialidad creativa de la aplicación orientada al diseño de relatos digitales personales. Rev. Educ. Digit. 2018, 33, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Moral Pérez, M.E.; Villalustre-Martínez, L.; Neira-Piñeiro, M.R. Teachers’ perception about the contribution of collaborative creation of digital storytelling to the communicative and digital competence in primary education schoolchildren. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 32, 342–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yussof, R.L.; Abas, H.; Paris, T.N.S.T. Affective engineering of background colour in digital storytelling for remedial students. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 68, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaman-Karoglu, A. Personal voices in higher education: A digital storytelling experience for pre-service teachers. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2016, 21, 1153–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T. Are you digitized? Ways to provide motivation for ELLs using digital storytelling. Int. J. Res. Stud. Educ. Technol. 2013, 2, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya-Ting, C.Y.; Wan-Chi, I.W. Digital storytelling for enhancing student academic achievement, critical thinking, and learning motivation: A year-long experimental study. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 339–352. [Google Scholar]

- Hava, K. Exploring the role of digital storytelling in student motivation and satisfaction in EFL education. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 34, 958–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.P.; Tai, S.J.D.; Liu, C.C. Enhancing language learning through creation: The effect of digital storytelling on student learning motivation and performance in a school English course. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2018, 66, 913–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.Y. Beyond elocution: Multimodal narrative discourse analysis of L2 storytelling. ReCALL 2019, 31, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires Pereira, I.S.; Campos, A. Constructing the pedagogy of multiliteracies. The role of focalisation in the development of critical analysis of multimodal narratives. Lang. Educ. 2023, 37, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, W.J.; Mathis, J.B. Multimodal assessments: Affording children labeled ‘at-risk’ expressive and receptive opportunities in the area of literacy. Lang. Educ. 2020, 34, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivone, M.F.; Jacobs, G.M.; Santosa, M.H. Information and communication technology to help students create their own books the dialogic way. Beyond Words 2020, 8, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Moral Pérez, M.E.; Bellver, M.C.; Guzmán Duque, A.P. Evaluación de la potencialidad creativa de aplicaciones móviles creadoras de relatos digitales para Educación Primaria. Ocnos 2019, 18, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Juste, R.; García Llamas, J.L.; Gil Pascual, J.A.; Galán González, A. Estadística Aplicada a la Educación; Pearson: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fontes de Gracia, S.; García-Gallego, C.; Quintanilla Cobián, L.; Rodríguez Fernández, R.; Rubio de Lemus, P.; Sarriá Sánchez, E. Fundamentos de Investigación en Psicología; Universidad Nacional a Distancia: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dhir, S.K.; Gupta, P. Formulation of Research Question and Composing Study Outcomes and Objectives. Indian Pediatr. 2021, 58, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.; Vossler, A. Methodological issues in focus group research: The example of investigating counsellors’ experiences of working with same-sex couples. Couns. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 31, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, O.G.; Montero, I. Métodos de Investigación en Psicología y Educación; McGrawHill: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zare, L.; Shahmari, M.; Dashti, S.; Jafarizadeh, R.; Nasiri, E. Comparison of the effect of teaching Bundle Branch Block of electrocardiogram through storytelling and lecture on learning and satisfaction of nursing students: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 56, 103216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cater, C.; Albayrak, T.; Caber, M.; Taylor, S. Flow, satisfaction and storytelling: A causal relationship? Evidence from scuba diving in Turkey. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1749–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Pitardi, V. How stories generate consumer engagement: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, S.; Fastrich, G.; Donnellan, E.; Jones, D.J.W.; Murayama, K. Curiosity and interest: A qualitative investigation of their similarities and differences. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2021, 150, 1732–1750. [Google Scholar]

- Kranz, J.; Melville, N.P.; Prat, N. Introduction to the Sustainability and Responsible Design Track. In Design Science Research for a New Society: Society 5.0: 18th International Conference on Design Science Research in Information Systems and Technology, DESRIST 2023, Pretoria, South Africa, 31 May–2 June 2023, Proceedings; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 13873, p. 446. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlieb, R.; Jahner, E.; Immordino-Yang, M.H.; Kaufman, S.B. How social-emotional imagination facilitates deep learning and creativity in the classroom. In Nurturing Creativity in the Classroom; Beghetto, R.A., Kaufman, J.C., Eds.; Cambridge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, B.; Pierson, M. A Multilevel Approach to Using Digital Storytelling in the Classroom. In Proceedings of the SITE 2005—Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference; Crawford, C., Carlsen, R., Gibson, I., McFerrin, K., Price, J., Weber, R., Willis, D., Eds.; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2005; pp. 708–716. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, S. Effective storytelling: Strategic business narrative techniques. Strategy Leadersh. 2006, 34, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervás, P. Computational drafting of plot structures for Russian folk tales. Cogn. Comput. 2016, 8, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, J.F. Digital storytelling: New opportunities for humanities scholarship and pedagogy. Cogent Arts Humanit. 2016, 3, 1181037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulu, H. Investigation of fourth grade primary school students’ creative writing and story elements in narrative text writing skills. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2019, 15, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, A.N.; Rule, A.C. Effects of teacher lesson introduction on second graders’ creativity in a science/literacy integrated unit on health and nutrition. Early Child. Educ. J. 2014, 42, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, R.W. Expertise and Structured Imagination in Creative Thinking: Reconsideration of an Old Question. In The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance; Ericsson, K.A., Hoffman, R.R., Kozbelt, A., Williams, A.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 812–834. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, R.M.; Gardner, B.; Kohm, K.; Bant, C.; Ciminello, A.; Moedt, K.; Romeo, L. The relationship between young children’s language abilities, creativity, play, and storytelling. Early Child Dev. Care 2019, 189, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).