A Systematic Review on Teachers’ Well-Being in the COVID-19 Era

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Research Question #1. How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact overall TWB across different educational levels?

- Research Question #2. What are the key determinants of TWB in terms of the challenges faced and leverage actions used by educators to maintain and advance their sense of well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic period?

- Research Question #3. What are the research design trends used in the examination of TWB throughout the COVID-19 pandemic period?

2. Teacher Well-Being in the COVID-19 Era

3. Rationale for the Current Review

4. Methodology Used in This Review

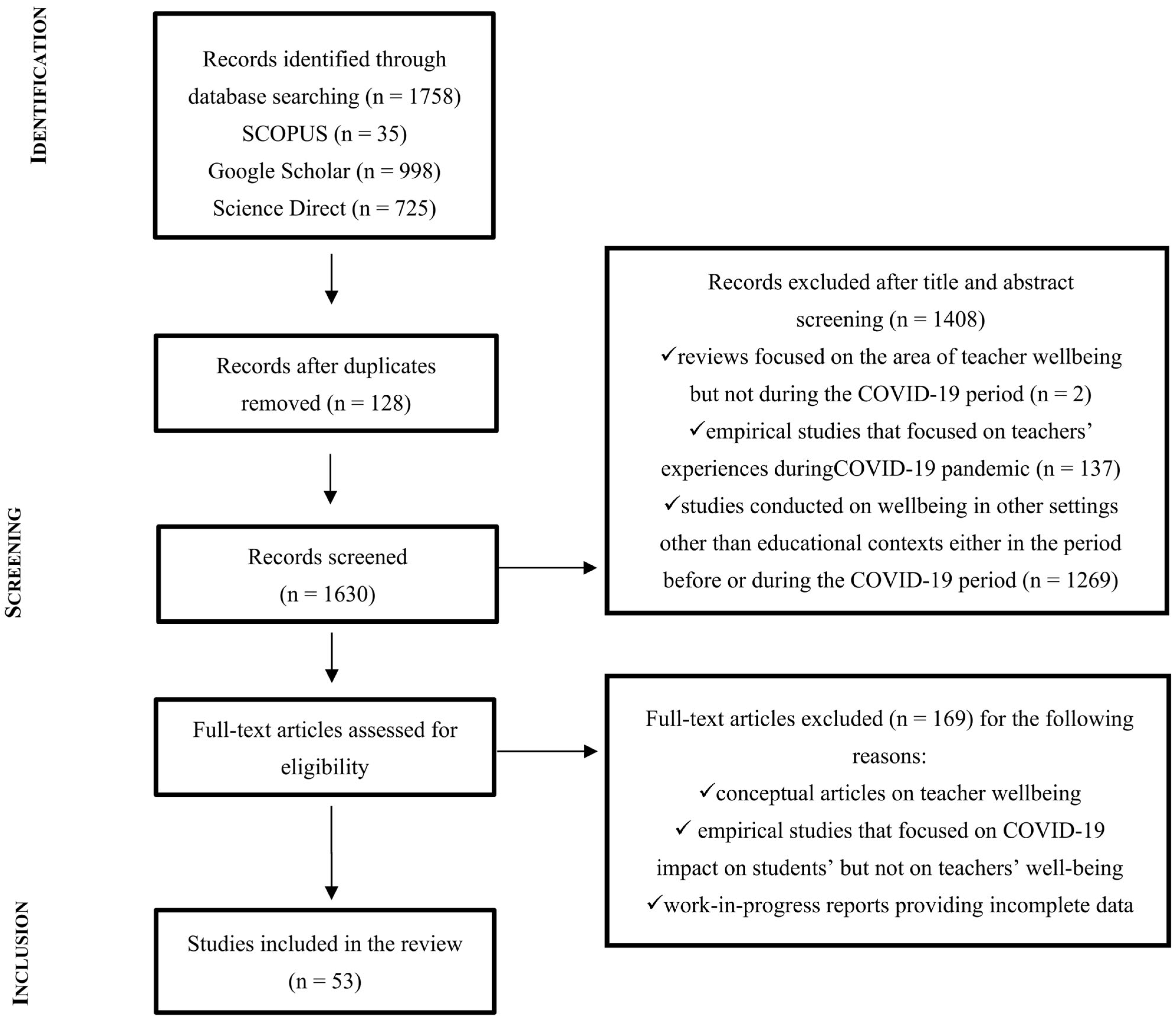

4.1. Search Strategy

4.2. Selection Criteria and Study Quality Assessment

4.2.1. Study Inclusion Criteria

- Published between 2020 and the first quarter of 2023.

- Written in English.

- Offered empirical evidence for the evaluation of TWB status across different educational levels during the COVID-19 period following a well-designed experimental research method instead of expressing a theoretical stance on the issue.

- Focused on the identification of key determinants that affected TWB during the COVID-19 pandemic within the context of primary, secondary, and higher education.

- Reported the coping strategies used by teachers in their effort to effectively overcome difficulties caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and sustain their well-being at an acceptable level.

4.2.2. Study Exclusion Criteria

- Not about TWB during the COVID-19 years.

- Not an empirical study based on a well-structured research method.

- Published in languages other than English.

- Published as work-in-progress reports or preliminary studies.

- Unpublished BA, MA, and PhD theses, as they have not undergone a peer-review process.

- Did not discuss implications related to TWB enhancement in times of crisis.

- Well-substantiated research questions in relation to TWB in the COVID-19 period.

- The research design (quantitative and/or qualitative) and data analysis methods used for the investigation of TWB in the COVID-19 pandemic in primary, secondary, and tertiary education.

- The goal of the studies and their scientific contribution in the area of teacher education and professional development addressed the TWB concept in empirical terms.

- A clear theoretical rationale for the study and its implications for practice and research in TWB in times of crisis.

4.3. Data Collection and Data Analysis

5. Results and Discussion

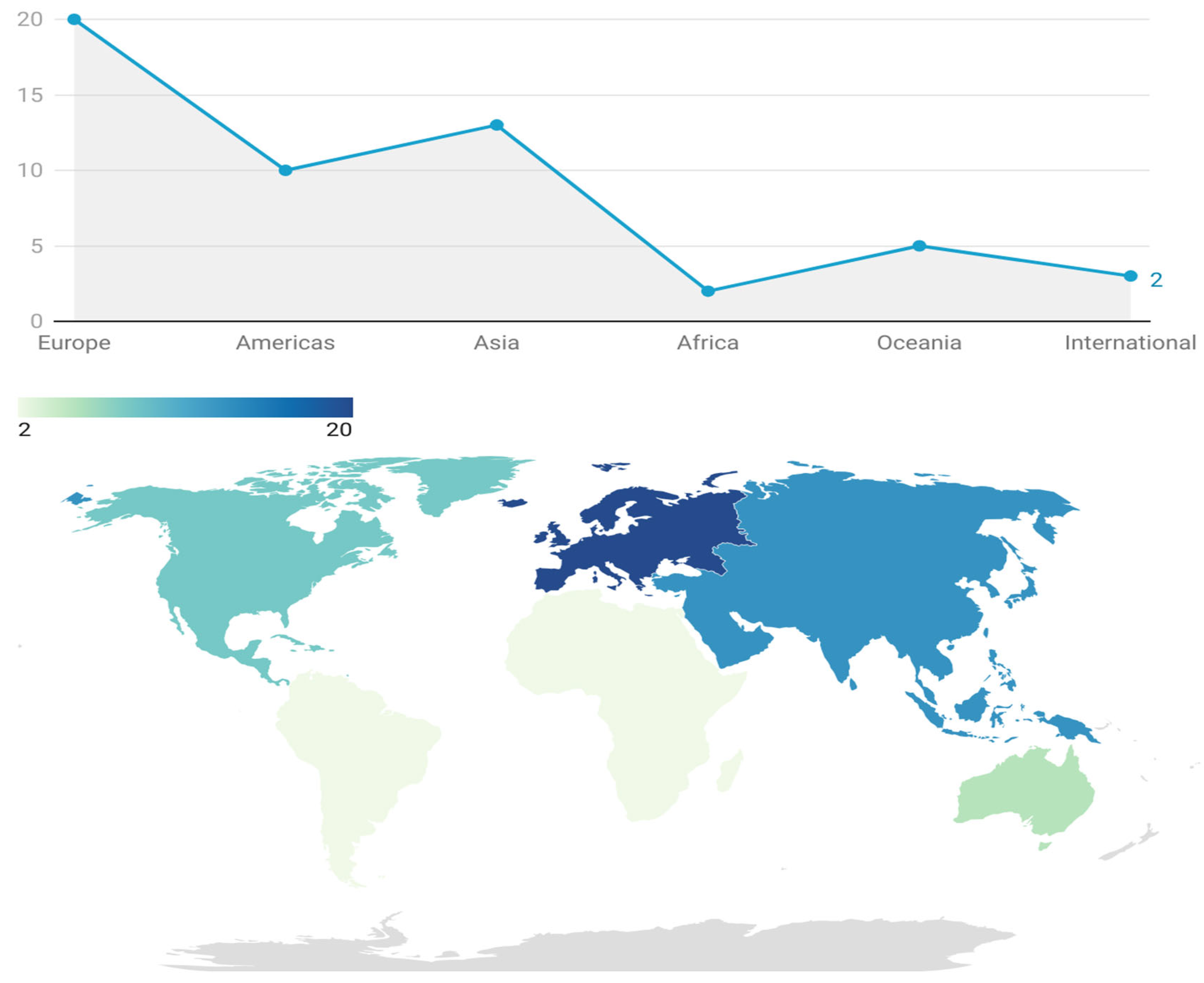

5.1. Profile of the Reviewed Studies

5.2. Review Findings

5.2.1. Research Question 1: TWB Overall Status during the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Studies in Preschool Education

- b.

- Studies in Primary and Secondary Education

- c.

- Higher Education

5.2.2. Research Question 2: TWB Stressors and Levers in the COVID-19 Era

- TWB Stressors during the COVID-19 Era

- b.

- TWB Levers during the COVID-19 Era

| Authors | Source | Research Design | Sample (N) | Type of Well-Being | Educational Level | Country | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ah-Kwon et al. (2022) [97] | Journal | Mixed method | 1434 | Professional, psychological, and physical | Primary | USA |

| 2. | Allen et al. (2020) [121] | Journal | Quantitative online survey (longitudinal) | 8000 | Psychological | Primary and secondary | UK |

| 3. | Alves et al. (2020) [105] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 1479 | Professional | Primary and secondary | Portugal |

| 4. | Anderson et al. (2021) [144] | Journal | Mixed method | 57 | Psychological | Primary | USA |

| 5. | Bartkowiak et al. (2022) [123] | Journal | Qualitative | 39 | Psychological | Higher | Poland |

| 6. | Billaudeau et al. (2022) [142] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 6899 | Professional | Primary and secondary | International |

| 7. | Billett et al. (2021) [114] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 534 | Psychological | Primary and secondary | Australia |

| 8. | Blaine (2022) [120] | Journal | Mixed method | 10 | Physical and psychological | Primary and secondary | Hong Kong |

| 9. | Chan et al. (2021) [133] | Journal | Mixed method | 181 | Professional and psychological | Primary | USA |

| 10. | Creely et al. (2021) [125] | Journal | Qualitative | 5 | Psychological | Higher | Australia |

| 11. | Eadie et al. (2022) [136] | Journal | Qualitative | 15 | Professional | Primary | Australia |

| 12. | Eadie et al. (2021) [98] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 232 | Professional | Primary | Australia |

| 13. | Egilmez (2022) [103] | Journal | Quantitative survey | 123 | Psychological | Pre-service | Turkey |

| 14. | Flores et al. (2022) [127] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 624 | Psychological | Primary and secondary | Chile |

| 15. | Froelich et al. (2022) [146] | Journal | Mixed method | 74 | Psychological | Secondary | Austria |

| 16. | Garcia-Alvarez et al. (2022) [147] | Journal | Quasi-experimental | 24 | Psychological | Primary, secondary, and vocational | Uruguay |

| 17. | Guoyan et al. (2021) [117] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 627 | Psychological | Higher | Pakistan and Malaysia |

| 18. | Hascher et al. (2021) [128] | Journal | Qualitative | 21 | Professional | Primary | Switzerland |

| 19. | Herman et al. (2021) [138] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 639 | Psychological | Primary and secondary | USA |

| 20. | Hilger et al. (2021) [109] | Journal | Quantitative online survey(longitudinal) | 207 | Professional | Primary, secondary, and special | Germany |

| 21. | Kamaruzaman & Surat (2021) [102] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 361 | Psychological | Primary | Malaysia |

| 22. | Karamushka et al. (2021) [118] | Journal | Longitudinal quantitative | 96 | Psychological | Secondary | Ukraine |

| 23. | Kasprzak & Mudlo-Glagoska (2022) [139] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 383 | Psychological | Primary and secondary | Poland |

| 24. | Kim et al. (2022) [135] | Journal | Longitudinal qualitative | 24 | Psychological | Primary and secondary | UK |

| 25. | Kotowski et al. (2022) [112] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 703 | Psychological and physical | Primary and secondary | USA |

| 26. | Kupers et al. (2022) [104] | Journal | Mixed method | 307 | Psychological | Primary, secondary, and vocational | The Netherlands |

| 27. | Lau et al. (2022) [115] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 366 | Psychological | Primary, secondary, and special | Hong Kong |

| 28. | Lee et al. (2022) [126] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 291 | Psychological | Pre-service | Hong Kong |

| 29. | Leong (2022) [149] | Journal | Qualitative | 3 | Psychological | Higher | Malaysia |

| 30. | McDonough & Lemon (2022) [131] | Journal | Qualitative | 137 | Psychological | Primary and secondary | Australia |

| 31. | MacIntyre et al. (2020) [134] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 634 | Psychological | Primary and secondary EFL | International |

| 32. | Nakijoba et al. (2022) [119] | Journal | Qualitative | 103 | Psychological and physical | Secondary | Uganda |

| 33. | Nong et al. (2022) [145] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 453 | Professional | Primary | China |

| 34. | Pace et al. (2022) [137] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 219 | Professional | Primary and secondary | Italy |

| 35. | Panadero et al. (2022) [107] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 936 | Psychological | Primary, secondary, and higher | Spain |

| 36. | Parkes et al. (2021) [99] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 1325 | Psychological | Primary | USA |

| 37. | Pourbahram & Sideghi (2022) [130] | Journal | Qualitative | 10 | Psychological | Secondary EFL | Iran |

| 38. | Poysa et al. (2022) [111] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 321 | Professional | Primary | Finland |

| 39. | Poysa et al. (2021) [110] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 279 | Professional | Primary | Finland |

| 40. | Rosli & Bakar (2021) [101] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 274 | Psychological | Primary | Malaysia |

| 41. | Shen & Slater (2021) [124] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 87 | Psychological | Higher | Northern Ireland |

| 42. | Sherief & Rehman (2022) [143] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 421 | Psychological | Higher | Malaysia |

| 43. | Sigursteinsdottir & Rafnsdottir (2022) [100] | Journal | Quantitative online survey(longitudinal) | 920 | Psychological and physical | Primary | Iceland |

| 44. | Smith & James (2021) [141] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 60 | Psychological | Secondary | Wales, UK |

| 45. | Stang-Rabrig et al. (2022) [108] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 3250 | Professional | Primary and secondary | Germany |

| 46. | Sulis et al. (2021) [122] | Journal | Qualitative | 6 | Psychological | EFL pre-service | International |

| 47. | Sultana et al. (2022) [132] | Journal | Qualitative | 34 | Psychological | Higher | Bangladesh |

| 48. | Trindade et al. (2021) [106] | Conference proceeding | Quantitative online survey | 595 | Psychological | Primary, secondary, and higher | Portugal |

| 49. | Walter & Fox (2021) [129] | Longitudinal Qualitative | 49 | Psychological and physical | Primary | USA | |

| 50. | Weibenfels et al. (2022) [116] | Journal | Quantitative online survey | 181 | Psychological | Primary and secondary | Germany |

| 51. | Wong et al. (2022) [113] | Journal | Qualitative | 8 | Psychological and physical | Primary ESOL | USA |

| 52. | Zadok-Gurman et al. (2021) [148] | Journal | Quasi-experimental | 67 | Psychological | Primary and secondary | Israel |

| 53. | Zewude et al. (2023) [140] | Journal | Quantitative survey | 836 | Psychological | Higher | Ethiopia |

5.2.3. Research Question 3: Research Trends in TWB in the COVID-19 Era

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Research Question 1: TWB Status during the COVID-19 Era

6.2. Research Question 2: TWB Stressors and Levers during the COVID-19 Era

6.3. Research Question 3: Research Trends on TWB during the COVID-19 Era

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Silver, R.C.; Everall, I. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, G.; Parmigiani, B.; Amerio, A.; Aguglia, A.; Sher, L.; Amore, M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM Int. J. Med. 2020, 113, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.R.; Heilemann, M.V.; Fauer, A.; Mead, M. A second pandemic: Mental health spillover from the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2020, 26, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaioannou, A.; Schinke, R.; Chang, Y.; Kim, Y.; Duda, J. Physical activity, health and well-being in an imposed social distanced world. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Physiol. 2020, 18, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, M.; Hope, H.; Ford, T.; Hatch, S.; Hotopf, M.; John, A.; Kontopantelis, E.; Webb, R.; Wessely, S.; McManus, S.; et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerstein, S.; König, C.; Dreisörner, T.; Frey, A. Effects of COVID-19-Related School Closures on Student Achievement-A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 746289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhfeld, M.; Soland, J.; Tarasawa, B.; Johnson, A.; Ruzek, E.; Liu, J. Projecting the potential impact of COVID-19school closures on academic achievement. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Guimond, F.A.; Bergeron, J.; St-Amand, J.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Gagnon, M. Changes in students’ achievement motivation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: A function of extraversion/introversion? Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, K.; Clark, S.; McGrane, A.; Rock, N.; Burke, L.; Boyle, N.; Joksimovic, N.; Marshall, K. A qualitative study of child and adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.; Russell, S.; Saulle, R.; Croker, H.; Stansfield, C.; Packer, J.; Nicholls, D.; Goddings, A.-L.; Bonell, C.; Hudson, L.; et al. School Closures During Social Lockdown and Mental Health, Health Behaviors, and Well-being Among Children and Adolescents During the First COVID-19 Wave: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Silva, D.F.; Cobucci, R.N.; Lima, S.C.; de Andrade, F.B. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review. Medicine 2021, 100, e27684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottiani, J.H.; Duran, C.A.K.; Pas, E.T.; Bradshaw, C.P. Teacher stress and burnout in urban middle schools: Associations with job demands, resources, and effective classroom practices. J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 77, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacIntyre, P.; Ross, J.; Talbot, K.; Mercer, S.; Gregersen, T.; Banga, C.A. Stressors, personality and wellbeing among language teachers. System 2019, 82, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, L.; Kennedy, K.; Shelton, C.; Dalal, M.; McAllister, L.; Huyett, S. Incremental progress: Re-examining field experiences in K-12 online learning contexts in the United States. J. Online Learn. Res. 2016, 2, 303–326. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/174116/ (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Winter, E.; Costello, A.; O’Brien, M.; Hickey, G. Teachers’ use of technology and the impact of COVID-19. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2021, 40, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino-Díaz, L.; Fernandez-Caminero, G.; Hernandez-Lloret, C.-M.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, H.; Alvarez-Castillo, J.-L. Analyzing the impact of COVID-19 on education professionals. Toward a paradigm shift: ICT and neuroeducation as a binomial of action. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aperribai, L.; Cortabarria, L.; Aguirre, T.; Verche, E.; Borges, A. Teacher’s physical activity and mental health during lockdown due to the COVID-2019pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 577886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver-Thomas, D.; Leung, M.; Burns, D. California Teachers and COVID-19: How the Pandemic Is Impacting the Teacher Workforce; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/california-covid-19-teacher-workforce (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Skaalvik, E.M.; Skaalvik, S. Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, U.; Richter, D.; Lüdtke, O. Teachers’ emotional exhaustion is negatively related to students’ achievement: Evidence from a large-scale assessment study. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 108, 1193–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokal, L.J.; Eblie Trudel, L.G.; Babb, J.C. Canadian teachers’ attitudes toward change, efficacy, and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2020, 1, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASUWT. COVID-19 Impacts on Teacher Mental Health Exposed. 2020. Available online: https:www.nasuwt.org.uk/article-listing/covid-impacts-onteacher-mental-health-exposed.html (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Teachers and Parents of K-12 Students; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Greenier, V.; Derakhshan, A.; Fathi, J. Emotion regulation and psychological well-being in teacher work engagement: A case study of British and Iranian English language teachers. System 2021, 97, 102446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J.M.; Gkonou, C.; Mercer, S. Do ESL/EFL Teachers’ Emotional Intelligence, Teaching Experience, Proficiency and Gender Affect Their Classroom Practice? In Emotions in Second Language Teaching; Agudo, J.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S.; Gregersen, T. Teacher Wellbeing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, S.; Oberdorfer, P.; Saleem, M. Helping language teachers to thrive: Using positive psychology to promote teachers’ professional well-being. In Positive Psychology Perspectives on Foreign Language Learning and Teaching; Gabryś-Barker, D., Gałajda, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, R.; Daly, A.; Huyton, J.; Sanders, L. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2012, 2, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. How’s Life? 2015: Measuring Wellbeing; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. WHO Remains Firmly Committed to the Principles Set Out in the Preamble to the Constitution; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Lucas, R.E. Personality, culture, and subjective well- being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 4, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E. Teacher Well-Being: Looking after Yourself and Your Career in the Classroom; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gillett-Swan, J.K.; Sargeant, J. Wellbeing as a process of accrual: Beyond subjectivity and beyond the moment. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 121, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Placa, V.; McNaught, A.; Knight, A. Discourse on wellbeing in research and practice. Int. J. Wellbeing 2013, 3, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S. An agenda for well-being in ELT: An ecological perspective. ELT J. 2021, 75, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, F.; Price, D.; Graham, A.; Morrison, A. Teacher Wellbeing: A Review of the Literature; Association of Independent Schools of NSW: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Scollon, C.; Lucas, R. The evolving concept of subjective wellbeing. Adv. Cell Aging Gerontol. 2003, 15, 187–219. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, G. Wellbeing and Flourishing. In The Palgrave Handbook of Positive Education; Kernand, M.L., Wehmeyer, M.L., Eds.; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V.; Waterman, A. Eudaimonia and Its Distinction from Hedonia: Developing a Classification and Terminology for Understanding Conceptual and Operational Definitions. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 15, 1425–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B. The contours of positive human health. Psychol. Inq. 1998, 9, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Boylan, J.M.; Kirsch, J.A. Eudaimonic and Hedonic Well-Being: An Integrative Perspective with Linkages to Sociodemographic Factors and Health; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C.D. Psychological Well-Being in Adult Life. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1995, 4, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Eudaimonic well-being: Highlights from 25 years of inquiry. In Diversity in Harmony—Insights from Psychology: Proceedings of the 31st International Congress of Psychology; Shigemasu, K., Kuwano, S., Sato, T., Matsuzawa, T., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V. The complementary roles of eudaimonia and hedonia and how they can be pursued in practice. In Positive Psychology in Practice; Joseph, S., Linley, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 216–246. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, A.S. Reconsidering happiness: A eudaimonist’ s perspective. J. Posit. Psychol. 2008, 3, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lovett, N.; Lovett, T. Wellbeing in education: Staff matter. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2016, 6, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.L.; Waters, L.; Adler, A.; White, M. Assessing employee wellbeing in schools using a multifaceted approach: Associations with physical health, life satisfaction, and professional thriving. Psychology 2014, 05, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, T.; McGrath, H. PROSPER: A new framework for positive education. Psychol. Well-Being Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.; Salanova, M. Burnout, boredom and engagement at the workplace. In An Introduction to Contemporary Work Psychology; Peeters, M.C., Jonge, J., Taris, T.W., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 293–320. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Dual processes at work in a call center: An application of the job demands-resources model. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2003, 12, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Zenger, M.; Brähler, E.; Spitzer, S.; Scheuch, K.; Seibt, R. Effort–reward imbalance and mental health problems in 1074 German teachers, compared with those in the general population. Stress Health 2014, 32, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumming, T. Early childhood educators’ well-being: An updated review of the literature. Early Child. Educ. J. 2017, 45, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, C.; Murphy, M. Burnout in Irish teachers: Investigating the role of individual differences, work environment and coping factors. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 50, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, A.; De Bloom, J.; Kinnunen, U. Relationships between Recovery Experiences and Well-Being Among Younger and Older Teachers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, B.P.; Hoff, E. Person-Centered and Variable-Centered Approaches to Longitudinal Data. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2006, 52, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Quinn, P.D.; Seligman, M.E.P. Positive predictors of teacher effectiveness. J. Posit. Psychol. 2009, 4, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branand, B.; Nakamura, J. The well-being of teachers and professors. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Positivity and Strengths-Based Approaches at Work; Oades, L.G., Steger, M.F., Delle Fave, A., Passmore, J., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 466–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, K. Testing the main determinants of teachers’ professional well-being by using a mixed method. Teach. Dev. 2015, 19, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, S.; Eshet, R. Spiral effects of teachers’ emotions and emotion regulation strategies: Evidence from a daily diary study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 73, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrup, K.; Klusmann, U.; Ludtke, O.; Gollner, R.; Trautwein, U. Student misbehavior and teacher well-being: Testing the mediating role of the teacher- student relationship. Learn. Instr. 2018, 58, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T. Well-being and learning in school. In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning; Seel, N.M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 3453–3456. [Google Scholar]

- Bower, J.M.; Carroll, A.-M. Capturing real-time emotional states and triggers for teachers through the teacher wellbeing web-based application t*: A pilot study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 65, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viac, C.; Fraser, P. Teachers’ Well-Being: A Framework for Data Collection and Analysis; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/teachers-well-being_c36fc9d3-en (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Talbot, K.; Mercer, S. Language teacher well-being. In Research Questions in Language Education and Applied Linguistics; Mohebbi, H., Coombe, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 567–572. [Google Scholar]

- Aelterman, A.; Engels, N.; Van Petegem, K.; Verhaeghe, J.P. The wellbeing of teachers in Flanders: The importance of a supportive school culture. Educ. Stud. 2007, 33, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson, C.; Åkerlund, M.; Graci, E.; Cedstrand, E.; Archer, T. Teacher team effectiveness and teacher’s well-being. Clin. Exp. Psychol. 2016, 2, 1000130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, A.; Maxwell, B. Supporting and inhibiting the well-being of early career secondary school teachers: Extending self-determination theory. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 43, 168–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, F.; Price, D. (Eds.) Nurturing Wellbeing Development in Education: From Little Things, Big Things Grow; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Acton, R.; Glasgow, P. Teacher wellbeing in neoliberal contexts: A review of the literature. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 40, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Kenyon, K.M.; Bullough, R.V.; MacKay, K.L.; Marshall, E.E. Preschool teacher well-being: A review of the literature. Early Child. Educ. J. 2014, 42, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T.; Waber, J. Teacher wellbeing: A systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educ. Res. Rev. 2021, 34, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, S.A.; Olaleye, E.O. The imperative of students and teachers’ well-being in Finnish university: A bibliometric approach. In ICERI 2022. Proceedings of the 15th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation. Conference Proceedings, Seville, Spain, 7–9 November 2022; Chova, L.G., Martínez, A.L., Lees, J., Eds.; IATED: Valencia, Spain, 2022; pp. 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Gascó, V.; Gómez-Domínguez, M.T.; Soto-Rubio, A.; Díaz-Rodríguez, L.; Navarro-Mateu, D. Stay at home and teach: A comparative study of psychosocial risks between Spain and Mexico during the pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 566900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyżalski, J.; Poleszak, W. Polish Teachers’ Stress, Well-being and Mental Health During COVID-19 Emergency Remote Education—A Review of the Empirical Data. Lub. Rocz. Pedagog. 2022, 41, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, D.; Soler, M.J.; Achard-Braga, L. Psychological Well-Being in Teachers During and Post-Covid-19: Positive Psychology Interventions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 769363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchenham, B.; Brereton, O.P.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Bailey, J.; Linkman, S. Systematic literature reviews in software engineering–a systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2009, 51, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Watson, R.T. Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Q. 2002, xiii–xxiii. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, L. Systematic Reviewing; University of Surrey: Guildford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tikito, I.; Souissi, N. Meta-analysis of systematic literature review methods. Int. J. Mod. Educ. Comput. Sci. 2019, 11, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.; Oliver, S.; Thomas, J. Introducing systematic reviews. In An Introduction to Systematic Reviews, 2nd ed.; Gough, D., Oliver, S., Thomas, J., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA group. Preferred reporting itemsfor systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchenham, B.A. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering (Version 2.3); EBSE Technical Report; Keele University and University of Durham: Staffordshire, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Punch, K. Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches; Sage: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Na’imah, T.; Kasanah, R.; Rahmasari Qurrota Aeni, P.S. Systematic Review on The Factors That Influence Well-Being Among Teachers. Sains Hum. 2021, 13, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Support. Teacher Wellbeing Index; Education Support: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ah-Kwon, K.-A.; Ford, T.G.; Tsotsoros, J.; Randall, K.; Malek-Lasater, A.; Kim, S.G. Challenges in Working Conditions and Well-Being of Early Childhood Teachers by Teaching Modality during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eadie, P.; Levickis, P.; Murray, L.; Page, J.; Elek, C.; Church, A. Early Childhood Educators’ Wellbeing during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Early Child. Educ. J. 2021, 49, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, K.A.; Russell, J.A.; Bauer, W.I.; Miksza, P. The Well-being and Instructional Experiences of K-12 Music Educators: Starting a New School Year During a Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 701189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigursteinsdottir, H.; Rafnsdottir, G.L. The Well-Being of Primary School Teachers duringCOVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosli, A.M.; Bakar, A.Y.A. The Mental Health State and Psychological Well-Being of School Teachers during COVID-19 Pandemic in Malaysia. Bisma J. Couns. 2021, 5, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaruzaman, M.; Surat, S. Teachers Psychological Well Being during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egilmez, O.H. COVID-19 Fears and Psychological Well-being of Pre-service Music teachers. Educ. Policy Anal. Strateg. Res. 2022, 17, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupers, E.; Mouw, J.M.; Fokkens-Bruinsma, M. Teaching in times of COVID-19: A mixed-method study into teachers’ teaching practices, psychological needs, stress and well-being. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 115, 103724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.; Lopes, T.; Precioso, J. Teachers’ well-being in times of Covid-19 pandemic: Factors that explain professional well-being. Int. J. Educ. Res. Innov. 2020, 15, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, B.M.M.C.; Pocinho, R.F.S.; Afonso, P.J.M.; Santos, D.F.C.; Silva, P.N.M.; Silveira, P.A.A.L.; Santos, G.A.R. COVID-19 and the Educational Area: Emotional Management and Well-Being in Teachers. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality (TEEM’21), Barcelona, Spain, 26–29 October 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E.; Fraile, J.; Pinedo, L.; Rodríguez-Hernández, C.; Balerdi, E.; Díez, F. Teachers’ Well-Being, Emotions, and Motivation During Emergency Remote Teaching Due to COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 826828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang-Rabrig, J.; Bruggerman, T.; Lorenz, R.; McElvany, N. Teachers’ occupational well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of resources and demands. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 117, 103803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilger, K.J.E.; Scheibe, S.; Frenzel, A.C.; Keller, M.M. Exceptional Circumstances: Changes in Teachers’ Work Characteristics and Wellbeing during COVID-19 lockdown. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 516–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöysä, S.; Pakarinen, E.; Lerkkanen, M.K. Patterns of Teachers’ Occupational Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Relations to Experiences of Exhaustion, Recovery, and Interactional Styles of Teaching. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 699785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöysä, S.; Pakarinen, E.; Lerkkanen, M.-K. Profiles of Work Engagement and Work-Related Effort and Reward Among Teachers: Associations to Occupational Well-Being and Leader–Follower Relationship During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 861300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowski, S.E.; Davis, K.G.; Barratt, C.L. Teachers feeling the burden of COVID-19: Impact on well-being, stress and burnout. Work 2022, 71, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.-Y.; Pompeo-Fargnoli, A.; Harriott, W. Focusing on ESOL teachers’ well-being during COVID-19 and beyond. ELT J. 2022, 76, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, P.; Turner, K.; Li, X. Australian teacher stress, well-being, self-efficacy, and safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Sch. 2021, 60, 1394–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S.S.S.; Shum, E.N.Y.; Man, J.O.T.; Cheung, E.T.H.; Amoah, P.A.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Okan, O.; Dadaczynski, K. Teachers’ Well-Being and Associated Factors during theCOVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study in Hong Kong, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weißenfels, M.; Benick, M.; Perels, F. Teachers’ prerequisites for online teaching and learning: Individual differences and relations to well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 42, 1283–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guoyan, S.; Khaskheli, A.; Raza, S.A.; Khan, K.A.; Hakim, F. Teachers’ self-efficacy, mental well-being and continuance commitment of using learning management system during COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative study of Pakistan and Malaysia. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamushka, L.; Kredentser, O.; Tereshchenko, K.; Lazos, G.; Klochko, A. Relationship between Teacher Work Motivation and Well-being at Different Stages of covid-19 Lockdown. Soc. Welf. Interdiscip. Approach 2021, 11, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakijoba, R.; Mugabi, R.D.; Ayodeji, A. COVID-19 School Closures in Uganda and their Impact on the Well-being of Teachers in Private Institutions in Semi-urban District. Adv. J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 10, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaine, J. Teachers’ Mental Wellbeing during Ongoing School Closures in Hong Kong. Educ. J. 2022, 11, 137–150. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.; Jerrim, J.; Sims, S. How Did the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic affect Teacher Wellbeing? CEPEO Working Paper No. 20-15; Centre for Education Policy and Equalizing Opportunities, UCL: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sulis, G.; Mercer, S.; Mairitsch, A.; Babic, S.; Shin, S. Preservice language teacher wellbeing as a complex dynamic system. System 2021, 103, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak, G.; Krugiełka, A.; Dama, S.; Kostrzewa-Demczuk, P.; Gaweł-Luty, E. Academic Teachers about Their Productivity and a Sense of Well-Being in the Current COVID-19 Epidemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Slater, P. The effect of occupational stress and coping strategies on mental health and emotional wellbeing among university academic staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. Int. Educ. Stud. 2021, 14, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creely, E.; Laletas, S.; Fernandes, V.; Subban, P.; Southcott, J. University teachers’ well-being during a pandemic: The experiences of five academics. Res. Pap. Educ. 2021, 37, 1241–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S.Y.; Fung, W.K.; Datu, J.A.D.; Chung, K.K.H. Subjective and psychological well-being profiles among pre-service teachers in Hong Kong: Associations with teachers’ self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Rep. 2022; advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, J.; Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Escobar, M.; Irarrázaval, M. Well-Being and Mental Health in Teachers: The Life Impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T.; Beltman, S.; Mansfield, C. Swiss Primary Teachers’ Professional Well-Being During School Closure Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 687512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, H.L.; Fox, H.B. Understanding Teacher Well-being During the COVID-19 Pandemic Over Time: A Qualitative Longitudinal Study. J. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 21, 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pourbahram, R.; Sideghi, K. English as a Foreign Language Teachers’ Wellbeing amidst COVID-19 Pandemic. Appl. Res. Engl. Lang. 2022, 11, 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, S.; Lemon, N. ‘Stretched very thin’: The impact of COVID-19 on teachers’ work lives and well-being. Teach. Teach. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Roshid, M.M.; Haider, M.Z.; Khan, R.; Kabir, M.M.N.; Jahan, A. University Students’ and Teachers’ Wellbeing during COVID-19 in Bangladesh: A Qualitative Enquiry. Qual. Rep. 2022, 27, 1635–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.K.; Sharkey, J.D.; Lawrie, S.I.; Arch, D.A.N.; Nylund-Gibson, K. Elementary School Teacher Wellbeing and Supportive Measures amid COVID-19: An Exploratory Study. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Gregersen, T.; Mercer, S. Language teachers’ coping strategies during the COVID-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System 2020, 94, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.S.; Oxley, L.; Asbury, K. ‘My brain feels like a browser with 100 tabs open’: A longitudinal study of teachers’ mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 92, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eadie, P.; Murray, L.; Levickis, P.; Page, L.; Church, A.; Elek, C. Challenges and supports for educator well-being: Perspectives of Australian early childhood educators during the COVID-19 pandemic. Teach. Teach. 2022, 28, 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, F.; Sciotto, G.; Randazzo, N.A.; Macaluso, V. Teachers’ Work-Related Well-Being in Times of COVID-19: The Effects of Technostress and Online Teaching. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, K.C.; Sebastian, J.; Reinke, W.M.; Huang, F.L. Individual and School Predictors of Teacher Stress, Coping, and Wellness During the COVID-19 pandemic. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak, E.; Mudło-Głagolska, K. Teachers’ Well-Being Forced to Work from Home Due to COVID-19 Pandemic: Work Passion as a Mediator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewude, G.T.; Beyene, S.D.; Taye, B.; Sadouki, F.; Hercz, M. COVID-19 Stress and Teachers’ Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Sense of Coherence and Resilience. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.P.; James, A. The wellbeing of staff in a Welsh Secondary School before and after a COVID-19 lockdown. J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2021, 34, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billaudeau, N.; Alexander, S.; Magnard, L.; Temam, S.; Vercambre, M.-N. What Levers to Promote Teachers’ Wellbeing during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond: Lessons Learned from a 2021 Online Study in Six Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherief, S.R.; Rehman, S. Factors affecting educators’ psychological well-being among COVID-19 Pandemic: A Quantitative Approach. J. Int. Bus. Manag. 2022, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.C.; Bousselot, T.; Katz-Buoincontro, J.; Todd, J. Generating Buoyancy in a Seaof Uncertainty: Teachers Creativity and Well-Being During the COVID-19Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 614774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nong, L.; Ye, J.-H.; Hong, J.-C. The Impact of Empowering Leadership on Preschool Teachers’ Job Well-Being in the Context of COVID-19: A Perspective Based on Job Demands-Resources Model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 895664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, D.E.; Morinaj, J.; Guias, D.; Hobusch, U. Newly Qualified Teachers’ Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Testing a Social Support Intervention Through Design-Based Research. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 873797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, D.; Soler, M.J.; Cobo-Rendón, R.; Hernández-Lalinde, J. Positive Psychology Applied to Education in Practicing Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Personal Resources, Well-Being, and Teacher Training. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadok-Gurman, T.; Jakobovich, R.; Dvash, E.; Zafrani, K.; Rolnik, B.; Ganz, A.B.; Lev-Ari, S. Effect of Inquiry-Based Stress Reduction (IBSR) Intervention on Well-Being, Resilience and Burnout of Teachers during the COVID-19Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, D.C.P. Factors affecting the Psychological Wellbeing of Educators: A study on Private College Lecturers succeeding COVID-19 Pandemic. Borneo J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K.; Bryant, A. Grounded Theory. In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Given, L.M., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2007; Volumes 1–2, pp. 374–376. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.; Van Manen, M. Phenomenology. In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Given, L.M., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2007; Volumes 1–2, pp. 614–619. [Google Scholar]

- Hascher, T.; Beltman, S.; Mansfield, C. Teacher wellbeing and resilience: Towards an integrative model. Educ. Res. 2021, 63, 416–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, M.; Lovett, S. Sustaining the commitment and realizing the potential of highly promising teachers. Teach. Teach. 2015, 21, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, L. Positive education pedagogy: Shifting teacher mindsets, practice, and language to make wellbeing visible in classrooms’. In The Palgrave Handbook of Positive Education; Kern, M.L., Wehmeyer, M.L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Hyler, M.E. Preparing educators for the time of COVID … and beyond. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Katsarou, E.; Chatzipanagiotou, P.; Sougari, A.-M. A Systematic Review on Teachers’ Well-Being in the COVID-19 Era. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090927

Katsarou E, Chatzipanagiotou P, Sougari A-M. A Systematic Review on Teachers’ Well-Being in the COVID-19 Era. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(9):927. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090927

Chicago/Turabian StyleKatsarou, Eirene, Paraskevi Chatzipanagiotou, and Areti-Maria Sougari. 2023. "A Systematic Review on Teachers’ Well-Being in the COVID-19 Era" Education Sciences 13, no. 9: 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090927

APA StyleKatsarou, E., Chatzipanagiotou, P., & Sougari, A.-M. (2023). A Systematic Review on Teachers’ Well-Being in the COVID-19 Era. Education Sciences, 13(9), 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090927