Abstract

Education support staff work closely with students with disability, yet often receive little training or professional learning in evidence-based practices. This study sought to provide an initial indication of the effectiveness of novel, co-designed, evidence-based online professional learning courses (AllPlay Learn) for education support staff. A total of 323 education support staff working in primary and secondary schools in Victoria, Australia, completed the courses and participated in this study. The results indicated significant improvements in their self-reported knowledge about disability (r = 0.68 and 0.71) and self-efficacy in engaging in inclusive classroom practices (r = 0.62 and 0.62) after taking part in the professional learning course. Analysis of open-ended questions found further support for these gains. These findings provide support for co-designed, evidence-based online professional learning that addresses disability-specific domains of inclusive classroom practices in education.

1. Introduction

Inclusive education has become a global focus for educational policy and reforms, informed by international declarations identifying the right of students with disability to access education on the same basis as their peers [1,2]. Many developed nations have ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities [3], which sets out the rights of students with disability to access the general education system. However, the definition and implementation of inclusive practices within educational settings have seen variable levels of application and, thereby, success [4,5].

Under the Disability Discrimination Act (1992) and Disability Standards for Education (2005), Australian students with disability have the clearly defined right to access an education on an equal basis to that of their peers [6,7]. The application of these rights, however—through the provision of inclusive education—has experienced variable success. The Victorian Government Department of Education’s 2016 review of the Program for Students with Disabilities identified numerous barriers and challenges to the inclusion of students with disability in Victoria (Australia) including a lack of consistency in professional learning related to evidence-based approaches for supporting students in the classroom [8]. One key approach used by Victorian schools to support students with disability is the employment of education support staff (hereafter ES staff), known by different names internationally including paraprofessionals, teacher aides, and paraeducators. Over 20,000 ES staff are employed in Victoria and employment rates are projected to grow by more than 17% over the next five years [9], in part due to policies, legislation, and the impacts of implementation of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) [10]. ES staff engage in non-instructional roles to support teachers in primary and secondary schools [9]. However, research indicates that ES staff in Australia are frequently asked to take on instructional roles that fall outside of their employed role and training [10,11,12,13]. Research evaluating the role of ES staff has found mixed evidence for their impact on student outcomes. While general support provided by ES staff in the classroom appears to have positive impacts in terms of reducing off-task behaviours [14], this general support may also have negative impacts on the autonomy, social interactions, and learning outcomes of students with disability [10,15,16]. This is thought to be largely a result of inadequate training and supervision, ineffective practices (such as the transfer of instructional responsibilities from highly qualified teachers), and one-to-one support acting as a barrier to students’ interactions with their peers [10,16,17]. Conversely, when ES staff receive adequate training, clear communication from teachers, and time to plan effectively with teachers in a complementary role, there are positive impacts on the learning, social, and behavioural outcomes of students [10,14] and on teacher workload and stress [10,15].

1.1. ES Staff Professional Learning

The qualifications of ES staff in Australia vary considerably [18]. In Victoria, ES staff are not required to hold qualifications [9]. Consequently, only 17% of ES staff nationally hold a university-level qualification, 52% hold vocational training qualifications, and 31% hold no qualifications [9]. The inconsistent access of ES staff to training in evidence-based inclusive classroom practices (i.e., strategies or teaching practices found to be effective by multiple, high-quality experimental studies [19]) is of particular concern when considering that the provision of high-quality professional learning (PL) is recognised as a key component for creating inclusive education environments [2].

Only a small body of literature evaluates the effectiveness of PL for improving the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs of ES staff working in primary and secondary school settings [16,20], with some promising evidence identified [21,22]. In terms of inclusive practices, however, the literature, to date, provides mixed findings. Experiential PL (in which skill application and support are provided within natural learning contexts) appears to be more effective than didactic PL (dissemination of knowledge) [23]. Specifically, experiential activities effecting changes in inclusive practice in education include modelling, accountability, and performance feedback, whereas brief workshops that do not provide opportunities to apply learning to the classroom environment are relatively ineffective [20,24]. The quality of evidence evaluating PL for ES staff is variable, with much of the literature consisting of single-subject or narrative case study designs and limited use of clinical significance tests to establish its effects [22]. Some researchers have highlighted the importance of providing PL that addresses knowledge gaps within disability-specific domains, such as courses that cover the presentation of autism and evidence-based practices that can be used in the classroom [17,25].

1.2. Effective Professional Learning for ES Staff Knowledge and Self-Efficacy

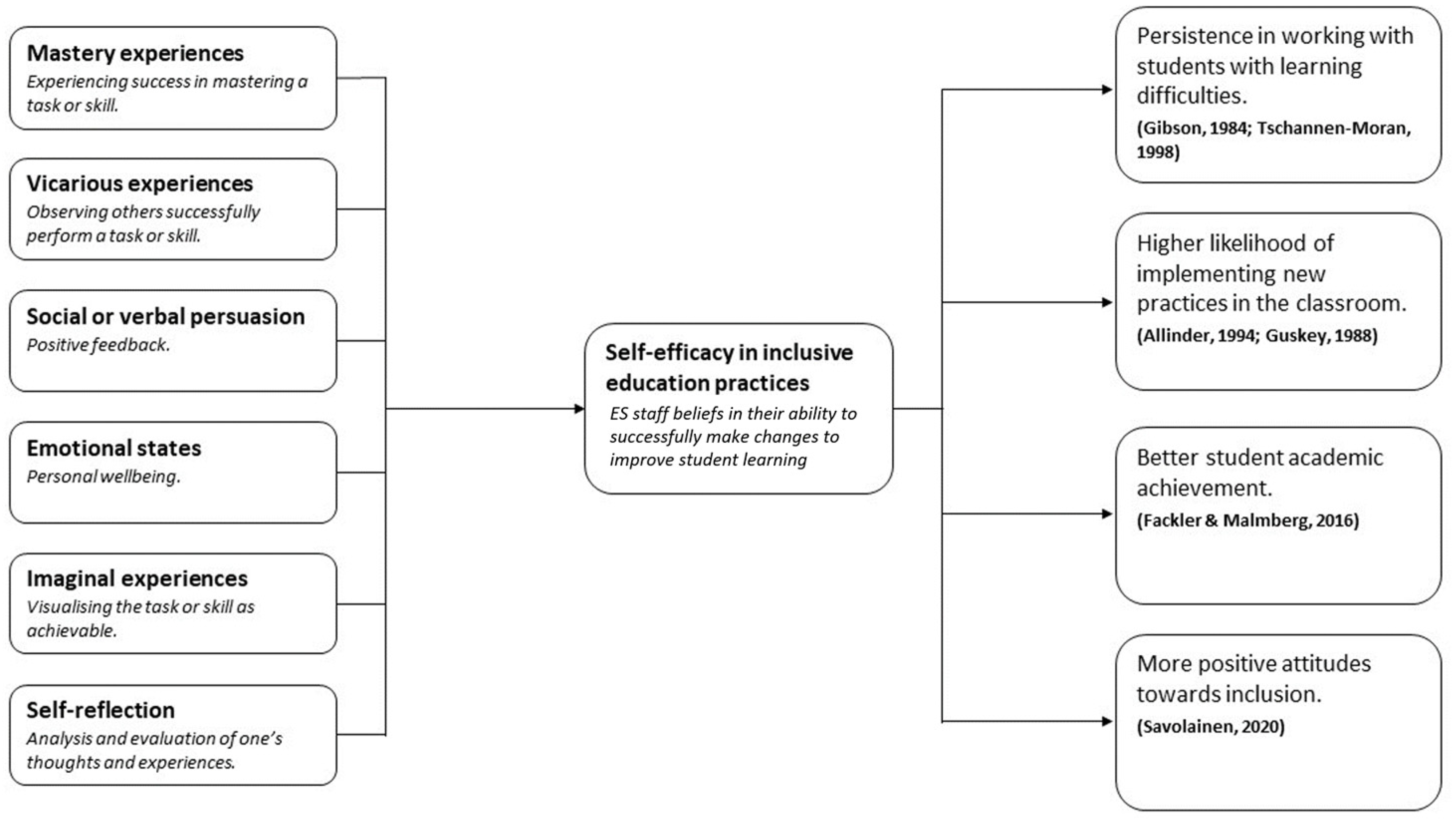

As illustrated in Figure 1, PL that increases ES staff self-efficacy may have positive effects on ES classroom practices [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Bandura’s social cognitive theory identifies four factors for building perceptions of self-efficacy [32,33], with other relevant factors including imaginal experiences [34] and self-reflection [35]. Each of these experiences increase the self-efficacy of learners by providing them with a model for success. As such, social cognitive theory differentiates between acquisition and application of knowledge [36], identifying self-efficacy as an important mechanism for translating acquisition of knowledge to application in real-world settings. PL has been shown to increase teacher self-efficacy in inclusive practices [37,38], lending support to the idea that for ES staff to apply their learning in the classroom, PL that increases their knowledge and efficacy beliefs is required.

Figure 1.

Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory and classroom practices [26,27,28,29,30,31].

One model that may help explain the interaction between PL and ES staff and student outcomes is Desimone’s [39] model of professional development. Desimone’s model suggests that as education professionals engage in effective PL, they experience gains in their underlying knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs which, in keeping with Bandura’s proposal that acquisition of knowledge may lead to application of knowledge, leads to changes in education practice and, thereby, improvements in student learning. While there are some criticisms of this model, there appears to be consensus across a range of PL models that engagement in PL can impact classroom practices, student outcomes, and the skills, knowledge, and beliefs of teachers and ES staff [40].

1.3. Online Professional Learning

The growing evidence identifying PL as a mechanism for improving self-efficacy and classroom practices of ES staff [10,16,22,23] highlights the importance of evaluating PL opportunities for ES staff. Unfortunately, PL opportunities for ES staff may be, in part, limited due to time and budget constraints [41,42], which indicates the importance of providing accessible and affordable PL opportunities. One learning forum which can be cost-effective and accessible—especially for rural locations—is the provision of online PL [43]. While didactic online PL courses should not act as a replacement for experiential PL [23], didactic online learning that (i) addresses knowledge gaps in disability-specific domains; (ii) prompts ES staff to consider how their learning may be applied in their work environment; and (iii) improves ES staff’s perceived self-efficacy may still have value for improving ES staff knowledge and self-efficacy in inclusive classroom practices [17,38,44]. This may, in line with Bandura’s social cognitive theory, have a flow-on effect for application of their knowledge in classrooms.

1.4. Introducing AllPlay Learn

The online asynchronous PL courses—AllPlay Learn: Inclusive Foundations for Children with Disabilities (see https://allplaylearn.org.au/courses/, 3 September 2023) are part of the AllPlay Learn platform launched in August 2019. AllPlay Learn was developed in partnership with the Victorian Department of Education and co-designed by a multidisciplinary team of experts, with stakeholders from disability peak organisations, government, students with disability and their families, and education professionals. It was founded at Deakin University and, in 2021, became part of Monash University. AllPlay Learn provides a novel approach to upskilling education professionals working with students with disability through using the dual processes of (i) co-design with end users and key stakeholders and (ii) translating decades of research on classroom practices that have been found to improve the learning and wellbeing outcomes of students with disability to provide a range of online guides, evidence-based strategies, resources, and PL courses designed to help create inclusive education environments for students with disability. In keeping with recommendations for identifying evidence-based inclusive classroom practices [19], a series of systematic reviews screening over 177,000 articles were conducted to identify evidence-based classroom strategies and shared strengths of students with disability. Strategies were differentiated by disability (anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, blind and low vision, cerebral palsy, communication disorders, deaf and hard of hearing, dyscalculia, dysgraphia, dyslexia, intellectual disability, oppositional defiant disorder, and physical disability) and setting (early childhood education and care; primary school; secondary school). AllPlay Learn is strengths-based and is maintained by a multi-disciplinary research team with expertise in disability, inclusion, clinical psychology, child development, education, and technology-enabled learning. A detailed description of the development of AllPlay Learn can be found on https://allplaylearn.org.au/about/ 3 September 2023.

The three AllPlay Learn courses contain an introduction outlining the overarching goals, six core lessons, and a minimum of two electives. Each course takes approximately 4–6 h to complete, with participants able to complete lessons at their own pace. The design of the course draws from several key principles for effective PL. These include segmentation (presenting information in short segments so learners can digest at their own pace [45]), inform and perform (communicating information while building strategic skills [45,46]), and informing with multimedia [45]. Further, Nolan and Molla’s principles of context, collegiality, criticality, and change are also applied, focusing on the specific environment where learning is required, collegial relationships, opportunity to question underlying beliefs, and changes in pedagogical knowledge, competences, and practices [47]. Similarly, as outlined in Table 1, the course design aligns with core features of PL identified by Desimone [39]. Aligned with Bandura’s theory, the courses provide imaginal experiences (through reflective questions and applied case studies), vicarious learning experiences (through masterclasses, illustration of practice videos, and applied case studies), and provide content to support staff wellbeing.

Table 1.

AllPlay Learn—alignment of course content with Desimone’s core features of professional development.

1.5. Study Aims

The number of ES staff employed in Victorian schools is steadily increasing; however, one in three employed ES staff do not hold relevant qualifications [18]. Online PL is a promising avenue for enhancing inclusive classroom practices [48]; however, there appears to be limited publications in the literature evaluating online PL for ES staff [49]. This is concerning given the notion that this lack of training may result in poorer inclusive classroom practices and, thereby, negative impacts on the outcomes of students with disability [10,16]. To address this gap, this study aims to explore whether online professional learning about disability-specific evidence-based classroom practices for education support staff improves the self-reported knowledge and self-efficacy of ES staff. This within-subject repeated-measures study explores changes in ES staff’s knowledge about disability and self-efficacy in engaging in inclusive classroom practices in primary and secondary school settings after completing a co-designed and evidence-based AllPlay Learn course. Since the AllPlay Learn courses (a) draw from evidence-based approaches to professional learning that have been found to increase knowledge and self-efficacy [17,38,39,44,45,47] and (b) were co-designed with end users to deliver simple and effective classroom strategies for improving the outcomes of students with disability, it was anticipated that preliminary effectiveness would be confirmed by ES staff’s self-reported gains in their knowledge about disability and self-efficacy in engaging in inclusive classroom practices. Participant responses to open-ended questions are used to further describe these gains, users’ views of the courses, and the potential implications for practice. In line with Desimone’s core features of professional learning [39] and Bandura’s social cognitive theory [32,33,34,35], we anticipate that participant responses to open-ended questions may provide insights into ways in which the courses’ use of content focus, active learning, coherence, and duration, alongside vicarious learning and imaginal and self-reflection experiences, facilitated knowledge acquisition and increased teachers’ self-efficacy and intent to apply their knowledge in the classroom.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were a convenience sample of 323 ES staff working in primary and secondary schools in Victoria, Australia, who participated in an AllPlay Learn PL course and consented to participate in the research. The sample was part of a larger study evaluating the effectiveness of the courses for teachers and educators working in early childhood education and care, primary school, and secondary school settings. Between August 2019 and June 2023, over 700 ES staff working in Victorian primary and secondary schools completed one of the courses. Of these, 323 ES staff (40%) completed one of the courses and consented to participation in the research component.

The PL courses were marketed through AllPlay Learn website and social media platforms, the Department of Education’s website and communications, the Victorian Institute of Teaching’s webpage of accredited programs, and through workshops, conferences, and exhibitions. To be included in this study, ES staff needed to be working in a learning support capacity in a Victorian Government primary or secondary school.

2.2. Procedure

Ethical approval was provided by the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee and ratified by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee. Ethics approval was also provided through the Victorian Department of Education’s Research in Schools and Early Childhood settings (RISEC) process. Users who chose to participate in research completed a five-minute questionnaire embedded within the course platform prior to beginning the course and at the end of the course. Participants completed the course online and at their own pace. No reminders or time limits for completion were sent to participants.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Data

Participants provided sociodemographic information in the pre-course questionnaire, which included gender, age, years of experience and level of qualification of the participants, and postcode and type of school the participants were employed at.

2.3.2. Self-Reported Knowledge about Disability

Participants rated their knowledge about students with disability on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “very poor” to “very good”. Each knowledge item corresponded to a lesson topic covering a specific disability. For primary school, there were five items pertaining to anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, communication disorders, and physical disability. For secondary school, as there were fewer lesson topics covering specific disabilities, there were three items pertaining to anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and autism spectrum disorder. The mean score was calculated such that scores could range from 1–5, with higher scores indicating a higher level of self-reported knowledge about students with disability. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for our sample, indicating good fit for primary and secondary school settings (α = 0.84 and 0.86, respectively) [50].

2.3.3. Perceived Self-Efficacy in Engaging in Inclusive Classroom Practices

Participants rated how competent they felt about a range of inclusive classroom practices on a ten-item 4-point Likert scale, with response options including “not at all”, “a little”, “quite”, and “very”. Competence was defined as “the ability to do something successfully or efficiently”. Inclusive classroom practices described in the scale included teaching students with disability, identifying strengths, setting goals, applying strategies, supporting emotions and behaviour, and working with families, teachers, or allied health professionals to support students with disability. The mean score was calculated such that scores could range from 1–4, with higher scores indicating a higher level of self-reported efficacy in inclusive classroom practices. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for our sample, indicating excellent fit for primary and secondary school settings (α = 0.94 and 0.95, respectively) [50].

2.3.4. Participants’ Feedback on Their Course Experiences

Participants were asked to answer two open-ended questions after completing the course: “What new knowledge did you gain from the professional learning course?” and “How could the professional learning course be improved?”. They were also asked to leave comments about the course and any other final reflections.

2.4. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27. Less than 5% of data were missing, and cases were excluded pair-wise. Descriptive statistics were generated for each measure, and assumptions were checked. Comparisons of the mean of the distribution of self-reported knowledge and self-efficacy before and after course completion using paired-sample t-tests were planned; however, due to the non-normality of the data, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were conducted instead. Effect sizes were calculated as Pearson’s r values, where values of 0.10, 0.20, and 0.30 were classified as relatively small, medium, and large, respectively [51]. Assuming a number of parameter values—namely medium effect size, α error probability of 0.05, and power of 0.80—a total sample size of 25 was required. Deductive analysis of the responses to the open-ended questions was conducted to understand any changes in ES staff’s self-reported knowledge and self-efficacy and participant experiences with the course. Two authors looked at the data together to reach consensus on coding. Codes reflected Bandura’s social cognitive theory and Desimone’s core features of professional development. Specifically, codes included content focus, active learning, coherence, duration, collective participation, vicarious learning, social persuasion, emotional states, imaginal experiences, self-reflection, gains in self-efficacy, acquisition of knowledge, and application of knowledge.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Sample

A total of 229 primary school ES staff (90% female) and 94 secondary school ES staff (90% female) enrolled in the PL courses and provided consent to participate in the research. Participant characteristics can be found in Table 2. The years of experience of ES staff ranged considerably, with the average number of years of experience being 6.55 (SD = 6.07) and 6.18 (SD = 6.90) for primary and secondary school ES staff, respectively. Most ES staff had achieved a certificate level of qualification. All participants who provided consent completed the training.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics.

3.2. ES Staff Knowledge about Disability and Self-Efficacy in Engaging in Inclusive Classroom Practices

As shown in Table 3, for primary school ES staff, the total scores significantly increased from pre-course to post-course completion for self-reported knowledge (n = 222, Z = −10.12, p < 0.001) and self-efficacy (n = 221, Z = −9.19, p < 0.001). There were 45 pairs and 35 pairs that showed no changes, and 16 pairs and 29 pairs that showed negative changes, from pre- to post-course for self-reported knowledge and efficacy, respectively. For secondary school ES staff, the total scores significantly increased from pre-course to post-course completion for self-reported knowledge (n = 89, Z = −6.72, p < 0.001) and self-efficacy (n = 87, Z = 5.77, p < 0.001). There were 25 pairs and 26 pairs that showed no changes, and 4 pairs and 10 pairs that showed negative changes, in self-reported knowledge from pre- to post-course. Effect sizes were all large.

Table 3.

Pre- and post-course changes in self-reported knowledge and efficacy in inclusive classroom practices.

Responses to open-ended questions were received from 26% of participants (85 participants). Participants described acquisitions of knowledge, most of which were related to content-focused learning, referring specifically to new knowledge gained about supporting students with specific disabilities (i.e., presentation, strengths, and strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, autism, communication disorder, and physical disability), and knowledge gains about maintaining their own wellbeing (emotional states). Some responses that illustrate these include “I learned many new strategies and approaches to work with different physical disabilities”, “Many aspects of behaviour or personality can be considered strengths”, “The ways that we can change many different things—like physical and intangible things—to help a student learn”, and “I had to take a step back and look at myself and how my emotions affect my job and well being”.

Twenty-one percent of participants who responded to open-ended questions engaged in self-reflection, which is a form of active learning, about new content learned in the course that helped them gain a new perspective. For example, one participant noted “I found that I became aware of not being set in my ideas/beliefs”, and another participant wrote “Asking why the goal is important is not something that I have done before and is pivotal in being meaningful for the student”. This process of self-reflection also provided coherence for some participants (22%), who described ways in which the course consolidated their learning, often alongside responses indicating gains in self-efficacy: “It made me feel more confident that the strategies I have been using are on the right track”, “Reinforcing my own knowledge is beneficial, as I can go on teaching confidently”, and “A great reminder to focus on the ‘Strengths Model’ and not the ‘Deficit Model’”.

Many participant responses indicated a preference for active learning through increased inclusion of videos as vicarious learning opportunities, with examples being “More short video clips to really visualise information” and “If real life application videos were included in terms of modelling the best responses to students who have a disability”. Applied case studies from the courses were also preferred by participants, in which two scaffolded examples, followed by opportunity to complete the same template in reference to a student they work with, provide imaginal experiences and vicarious learning opportunities: “I like the questions that had a prewritten scenario”, “more case studies to get some more practice in setting goals and applying strategies”, and “more real life examples”. Conversely, early-career staff reported that the use of applied case studies and reflection could be problematic if these did not reflect their relatively limited experiences (coherence), with one participant noting “These strategies are really only effective once you are in the applicable situation”, and another participant’s response suggesting that visualising what these could look like when working with students in future (imaginal experiences) might be more helpful: “Maybe instead of all being reflective, could incorporate ‘what if/if you were to work with’”.

A small number of participants (9%) explicitly described gains in their self-efficacy related to knowledge acquisition through the PL courses, with some examples including “Confidence to deal with children with disability and how to present something to make them understand” and “I feel I am much better equipped to deal with and support the children of different abilities”. Further, 19% of ES staff indicated intention to apply the knowledge gained. Some examples include: “This course made me rethink of students in the current room and how I can support them”, “I did pick up some more great strategies to use in the classroom.”, and “I gained a lot of new strategies that I could implement in my future teaching to better support my students”. Several participants did, however, indicate that the provision of course content solely via the platform increased the time it took to digest their learning (duration) as they then needed to write their own notes to refer back to when applying in the classroom: “Could be condensed somehow. Not sure how as all the information is valuable. I definitely spent more than 6 h on it, but that is with lots of note-taking involved” and “We all wanted to have the notes to be able to refer back to”.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to explore the preliminary effectiveness of the co-designed, evidence-based AllPlay Learn PL course for ES staff. In line with our hypotheses, significant increases were found in self-reported knowledge about disability and self-efficacy in engaging in inclusive classroom practices of ES staff after they took part in the PL course. These highly significant improvements are of particular interest when considering the level of experience of ES staff who completed the courses, who had, on average, six years of experience working in education settings (ranging from 0 years to 33 years). Analysis of open-ended questions found further support for these gains, with participant reflections indicating the courses were helpful for consolidating existing knowledge and/or gaining new knowledge or perspectives and helped them feel more equipped for their role.

4.1. Knowledge

The increase in self-reported knowledge aligns with previous research identifying that PL can result in knowledge gains for ES staff [21,22] and extends this research through the provision of effect sizes. The results were highly significant, and the effect sizes were large, indicating that the courses are likely to have practical relevance to ES staff.

Many participants identified two key areas of content-focused knowledge gained from the courses, namely strengths-based approaches to inclusive classroom practices and evidence-based approaches to supporting specific disabilities or behaviour. Strengths-based approaches have become increasingly adopted in educational settings [52,53] and are linked to increased wellbeing, confidence, engagement, and achievement of students at school [54,55,56,57]. Given previous research that has identified that general support provided by ES staff can have negative impacts on the autonomy and learning outcomes of students with disability [10,15,16], the reported gains in knowledge of strengths-based approaches highlight a promising area for PL to focus on.

The findings also support calls for PL that addresses knowledge gaps within disability-specific domains [17,25]. In particular, many participants cited classroom strategies for supporting students with a specific disability as amongst the most important knowledge gained from the courses, with further responses indicating an intent to apply those strategies, and a preference for further active learning opportunities that involve imaginal experiences and vicarious learning, such as applied case studies, to support the knowledge gains. These findings provide insights into the preliminary effectiveness of the courses for education support staff and highlight that active learning opportunities to increase knowledge in how to implement practical, evidence-based classroom strategies may be a particularly important inclusion in online professional learning for this cohort.

4.2. Self-Efficacy

The increase in self-reported self-efficacy aligns with previous research identifying that PL can result in self-efficacy gains in ES staff [37,38], with the large effect sizes extending previous findings through identifying that the increases observed are likely to have practical significance. Participant responses to open-ended questions further supported this finding. ES staff expressed increased confidence in their ability to apply inclusive classroom practices, highlighting a number of factors for building efficacy that were in keeping with theory, specifically vicarious experiences, imaginal experiences, and self-reflection [32]. It appeared that the course content may have provided coherence with the practices of some ES staff, with this reinforcement of their prior learning building their sense of efficacy. Vicarious experiences and self-reflection exercises appear to be promising approaches for online PL for ES staff. In particular, this study’s findings indicate that self-reflection exercises that ask ES staff to apply their learning to students they work with (i.e., visualise what the strategies may look like in action) have the potential to build self-efficacy and increase the likelihood that ES staff will apply their knowledge in the classroom. Further, the findings indicate that imaginal experiences may, at times, have more relevance for early-career ES staff than self-reflection tasks, given that some early-career ES staff may not have relevant experiences to reflect on.

The intention to apply learning indicated by some participants provides tentative support for the potential for online PL courses for ES staff that utilise content focus, active learning, vicarious experiences, imaginal experiences, and self-reflection to translate into changes to inclusive classroom practices. While this study was not intended to evaluate whether the observed changes in self-reported knowledge and self-efficacy translated into changes to inclusive classroom practices, it does highlight that co-designed, evidence-based online PL that incorporates activities explicitly designed to build knowledge and perceptions of self-efficacy may be a promising tool for improving inclusive classroom practices in ES staff.

4.3. Study and Professional Learning Course Limitations

While results indicated that the PL course resulted in significant improvements in the self-reported knowledge and self-efficacy of ES staff, several potential improvements to the courses were identified. ES staff expressed a preference for the courses to be designed with their specific role in mind, rather than catering to both teachers and ES staff. Further, ES staff indicated they would have liked it if more interactive or multimodal activities were included as well as further opportunities to reflect, observe, and apply learning. This may reflect a preference for active learning and self-reflection and imaginal experiences, in keeping with Desimone’s core features of PL [39] and Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy [35], respectively. Inclusion of more of these elements may further increase the effectiveness of the AllPlay Learn PL course.

A number of study design limitations constrain the conclusions that can be drawn from the current study. First, this study only aims to explore preliminary effectiveness of the PL courses and, as such, does not explore evidence of actual changes in practices. Second, the sample may not be representative of all ES staff. Participants chose to participate in both the PL and research, despite no requirements in Victoria to participate in PL [9], and the gender ratio for this study was not equal, with 90% of the sample being female. While this reflects the true gender ratios of ES staff in Victoria (90% female [18]), findings may not be generalisable to male ES staff or to ES staff who are less motivated to participate in PL. Finally, no comparison group was included. Future research should consider a range of recruitment strategies to increase representativeness and randomisation of participants to alternative PL.

4.4. Implications

The current study, which found significant and statistically meaningful improvements in disability-related knowledge and self-efficacy in an overall relatively experienced sample of ES staff, highlights promising areas for future research evaluating online PL designed for ES staff. First, our findings highlight that online PL for ES staff that addresses knowledge gaps in disability-specific domains is a promising area to focus on, particularly in strengths-based approaches. Further research that aims to understand specific knowledge and professional practice gaps for ES staff in these domains is needed. Second, these findings provide initial tentative support for the dual process used to develop the course content. That is, by engaging end users and stakeholders in a co-design process to translate research evidence on effective classroom practices that support the outcomes of students with disability, the resulting content may be effective for increasing self-reported knowledge and self-efficacy and be perceived as feasible and acceptable by education support staff. Third, online courses that incorporate content focus, active learning, vicarious experiences, imaginal experiences, and self-reflection may increase knowledge and self-efficacy in inclusive classroom practices of ES staff. Specifically, reflective exercises that involve imaginal experiences (i.e., ask ES staff to visualise how they might apply the knowledge with a student) and videos that model application of the knowledge appear to be highly valued by ES staff and may play an important role in increasing self-efficacy. However, the provision of content solely via a platform may increase the duration and, therefore, act as a barrier to applying learning in the classroom. Therefore, to further support translation into classroom practices, online courses should consider how they can incorporate or extend application of learning into the classroom itself. For example, provision of downloadable resources such as summaries of key learning or checklists to support implementation and monitoring could support successful translation of knowledge into ES staff practices. Further, teachers with high efficacy in inclusive classroom practices could support ES staff’s application of online content by providing further in-school mentoring and fidelity checks. Further evaluation of approaches such as these, using objective measures, is warranted.

5. Conclusions

This article sought to explore the preliminary effectiveness of the AllPlay Learn PL courses for ES staff working in Victorian primary and secondary schools. The findings identified increases in self-reported knowledge about disability and self-efficacy as a result of participation, with ES staff responses providing support for the premise that co-designed, evidence-based PL that uses content focus, active learning, vicarious experiences, imaginal experiences, and self-reflection may support changes in knowledge and perceptions of efficacy. These findings indicate that co-designed evidence-based online PL that addresses disability-specific domains of inclusive classroom practice shows promise for improving the knowledge and self-efficacy of ES staff working in primary and secondary school settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D.D. and A.M.; methodology, B.D.D. and A.M.; formal analysis, B.D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, B.D.D.; writing—review and editing, B.D.D., A.M., K.B., J.M. and N.J.R.; project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, N.J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The AllPlay Learn platform was developed in partnership with and with funding from the Victorian Department of Education. However, the Department does not have any role in any of the research studies conducted by the authors including data collection, analysis, and interpretation; writing of manuscripts; and the decision to submit this article for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Decla-ration of Helsinki and approved by the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (2018-173, 26 June 2018) and the Research in Schools and Early Childhood settings (RISEC) of the Victorian Department of Education (2018_003763, 29 June 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Research data can be accessed by emailing the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the school staff who participated in co-design of the professional learning coursess and the ES staff who participated in the professional learning course and research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- UNESCO. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality, Salamanca, Spain, 7–10 June 1994. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Towards Inclusion in Education: Status, Trends and Challenges: The UNESCO Salamanca Statement 25 Years on. France: UNESCO. 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374246 (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- United Nations General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2006. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Anastasiou, D.; Keller, C.E. Cross-National Differences in Special Education Coverage: An empirical analysis. Except. Child. 2014, 80, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göransson, K.; Nilholm, C. Conceptual diversities and empirical shortcomings—A critical analysis of research on inclusive education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2014, 29, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth). (Austl.). Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2016C00763 (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Disability Standards for Education 2005 (Cth). (Austl.). Available online: https://docs.education.gov.au/node/16354 (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Victorian Government Department of Education. Review of the Program for Students with Disabilities. 2016. Available online: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/about/department/PSD-Review-Report.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Victorian Department of Education [DE]. Recruitment in Schools. 2022. Available online: https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/recruitment-schools/policy-and-guidelines/qualifications (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Sharma, U.; Salend, S.J. Teaching Assistants in Inclusive Classrooms: A Systematic Analysis of the International Research. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 41, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, R. Teacher assistant support and deployment in mainstream schools. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2016, 20, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D.; Paatsch, L.; Toe, D. An Analysis of the Role of Teachers’ Aides in a State Secondary School: Perceptions of Teaching Staff and Teachers’ Aides. Australas. J. Spec. Educ. 2016, 40, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.R.; Aprile, K.T. ‘I can sort of slot into many different roles’: Examining teacher aide roles and their implications for practice. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2015, 35, 140–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, R.; Blatchford, P.; Bassett, P.; Brown, P.; Martin, C.; Russell, A. The wider pedagogical role of teaching assistants. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2011, 31, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatchford, P.; Russell, A.; Webster, R. Reassessing the Impact of Teaching Assistants: How Research Challenges Practice and Policy, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, M.E.; Carter, E.W. A Systematic Review of Paraprofessional-Delivered Educational Practices to Improve Outcomes for Students with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2013, 38, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, M.; Lamb, J.; Bartlett, B.; Datta, P. Autism Spectrum Disorder Coursework for Teachers and Teacher-aides: An Investigation of Courses Offered in Queensland, Australia. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 42, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. Labour Market Insights. 2022. Available online: https://labourmarketinsights.gov.au (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Cook, B.G.; Collins, L.W.; Cook, S.C.; Cook, L. Evidence-Based Reviews: How Evidence-Based Practices are Systematically Identified. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2020, 35, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispoli, M.; Neely, L.; Lang, R.; Ganz, J. Training paraprofessionals to implement interventions for people autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2011, 14, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layden, S.; Hendricks, D.; Inge, K.; Sima, A.; Erickson, D.; Avellone, L.; Wehman, P. Providing online professional development for paraprofessionals serving those with ASD: Evaluating a statewide initiative. J. Vocat. Rehabilit. 2018, 48, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, L.A.; Alperin, A.; Glover, T.A. A critical review of the professional development literature for paraprofessionals supporting students with externalizing behavior disorders. Psychol. Sch. 2020, 58, 742–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, V.L.; Smith, C.G. Training Paraprofessionals to Support Students with Disabilities: A Literature Review. Exceptionality 2015, 23, 170–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M.E.; Carter, E.W. Effects of a Professional Development Package to Prepare Special Education Paraprofessionals to Implement Evidence-Based Practice. J. Spec. Educ. 2015, 49, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, T.L.; Dimitriou, F.; Turko, K.; McPartland, J. Developing Undergraduate Coursework in Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 2646–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allinder, R.M. The Relationship Between Efficacy and the Instructional Practices of Special Education Teachers and Consultants. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 1994, 17, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fackler, S.; Malmberg, L.-E. Teachers’ self-efficacy in 14 OECD countries: Teacher, student group, school and leadership effects. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 56, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, S.; Dembo, M.H. Teacher efficacy: A construct validation. J. Educ. Psychol. 1984, 76, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskey, T.R. Teacher efficacy, self-concept, and attitudes toward the implementation of instructional innovation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1988, 4, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, H.; Malinen, O.-P.; Schwab, S. Teacher efficacy predicts teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion—A longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 26, 958–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, A.W.; Hoy, W.K. Teacher Efficacy: Its Meaning and Measure. Rev. Educ. Res. 1998, 68, 202–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy. In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior; Ramachaudran, V.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; Volume 4, pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Freeman, W.H.; Lightsey, R. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Maddux, J.E. Self-Efficacy, Adaptation, and Adjustment Theory, Research, and Application; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun, B. Adopting a stance: Bandura and Vygotsky on professional development. Res. Educ. 2019, 105, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horan, M.; Merrigan, C. Teachers’ perceptions of the effect of professional development on their efficacy to teach pupils with ASD in special classes. J. Incl. Educ. Irel. 2021, 32, 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, J.H. The Effect of Professional Development on Teacher Efficacy and Teachers’ Self-Analysis of Their Efficacy Change. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2016, 18, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L.M. Improving Impact Studies of Teachers’ Professional Development: Toward Better Conceptualizations and Measures. Educ. Res. 2009, 38, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylan, M.; Coldwell, M.; Maxwell, B.; Jordan, J. Rethinking models of professional learning as tools: A conceptual analysis to inform research and practice. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2018, 44, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, S.N.; McNaughton, D.; Light, J. Online Training for Paraeducators to Support the Communication of Young Children. J. Early Interv. 2014, 35, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.L.; Forbush, D.E.; Nelson, J. Live, Interactive paraprofessional training using internet technology: Description and evaluation. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2004, 19, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.A.; Miller, K.; Richman, T. Comparative study of high-quality professional development for high school biology in a face-to-face versus online delivery mode. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2020, 23, 68–80. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26926427 (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Ahadi, A.; Bower, M.; Singh, A.; Garrett, M. Online Professional Learning in Response to COVID-19—Towards Robust Evaluation. Futur. Internet 2021, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.C.; Mayer, R.E. E-Learning and the Science of Instruction: Proven Guidelines for Consumers and Designers of Mul-Timedia Learning; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, D.R. E-Learning in the 21st Century: A Community of Inquiry Framework for Research and Practice, 3rd ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, A.; Molla, T. Teacher professional learning in Early Childhood education: Insights from a mentoring program. Early Years 2016, 38, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio, B.L.; Hollingshead, A. Reaching out to Paraprofessionals: Engaging Professional Development Aligned with Universal Design for Learning Framework in Rural Communities. Rural. Spec. Educ. Q. 2017, 36, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, S.N.; Uitto, D.J.; Reinfelds, C.L.; D’agostino, S. A Systematic Review of Paraprofessional Training Materials. J. Spec. Educ. 2019, 52, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, D.V. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol. Assess. 1994, 6, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, G.E.; Szodorai, E.T. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 102, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, K.; Rawana, E.P.; MacArtthur, J. Implementation of a Strengths-Based Approach to Teaching in an Elementary School. J. Teach. Learn. 2012, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victorian Department of Education [DE]. Inclusive Education for Students with Disabilities. 2021. Available online: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/about/programs/Pages/Inclusive-education-for-students-with-disabilities.aspx (accessed on 3 September 2023).

- Galloway, R.; Reynolds, B.; Williamson, J. Strengths-based teaching and learning approaches for children: Perceptions and practices. J. Pedagog. Res. 2020, 4, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, D.; Swain, N.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. How “other people matter” in a classroom-based strengths intervention: Exploring interpersonal strategies and classroom outcomes. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 10, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Ernst, R.M.; Gillham, J.; Reivich, K.; Linkins, M. Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxf. Rev. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 2009, 35, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.A.; Waters, L.E. A case study of ‘The Good School:’ Examples of the use of Peterson’s strengths-based approach with students. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).