Education Policy Institutions’ Comprehension of the School as a Learning Organisation Approach: A Case Study of Latvia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

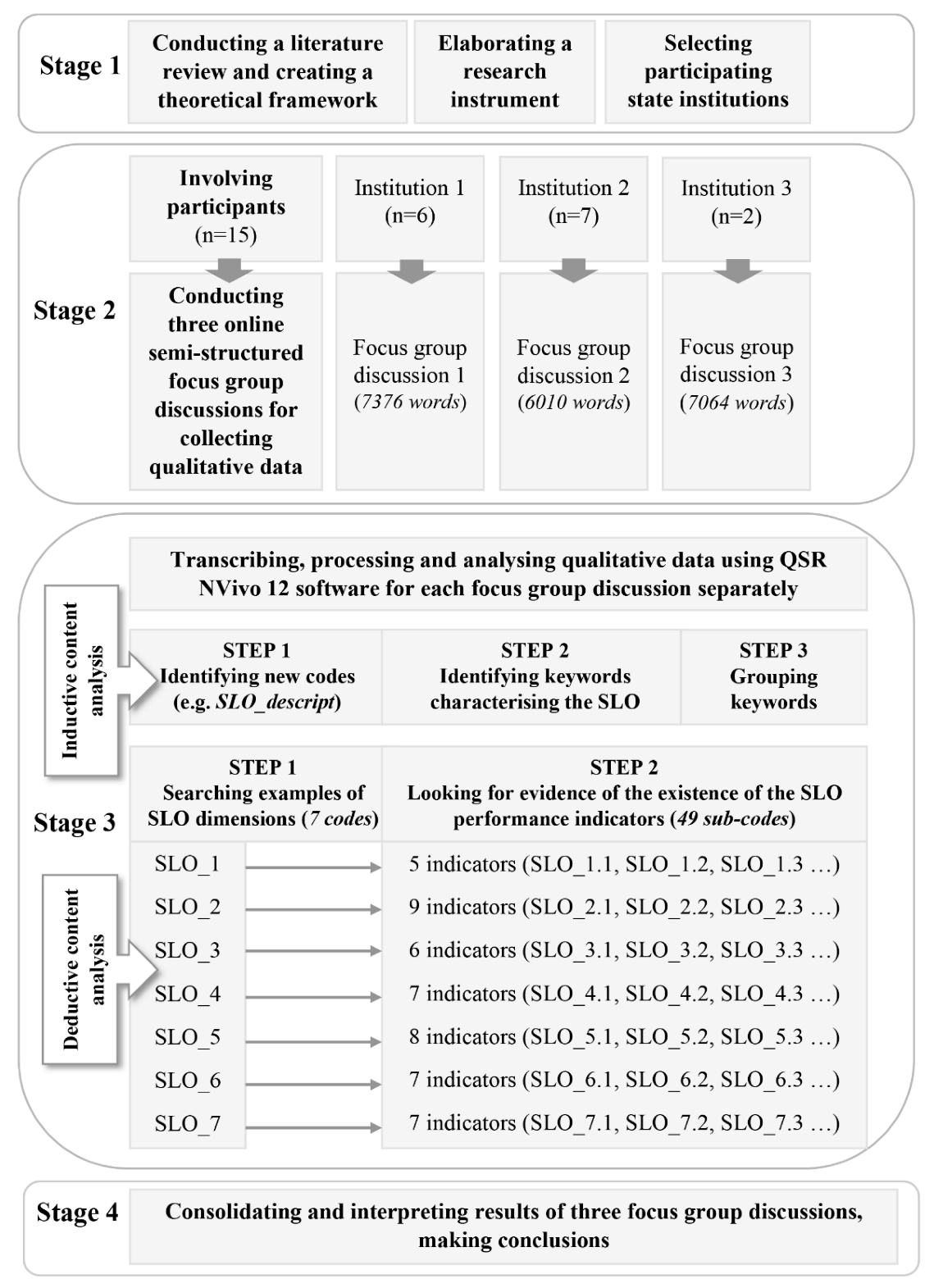

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Dimension of “Developing a Shared Vision Centred on the Learning of All Students”

3.2. Dimension of “Creating and Supporting Continuous Professional Learning for All Staff”

3.3. Dimension of “Promoting Team Learning and Collaboration among All Staff”

3.4. Dimension of “Establishing a Culture of Inquiry, Exploration and Innovation”

3.5. Dimension of “Embedding Systems for Collecting and Exchanging Knowledge and Learning”

3.6. Dimension of “Learning with and from the External Environment and Larger System”

3.7. Dimension of “Modelling and Growing Learning Leadership”

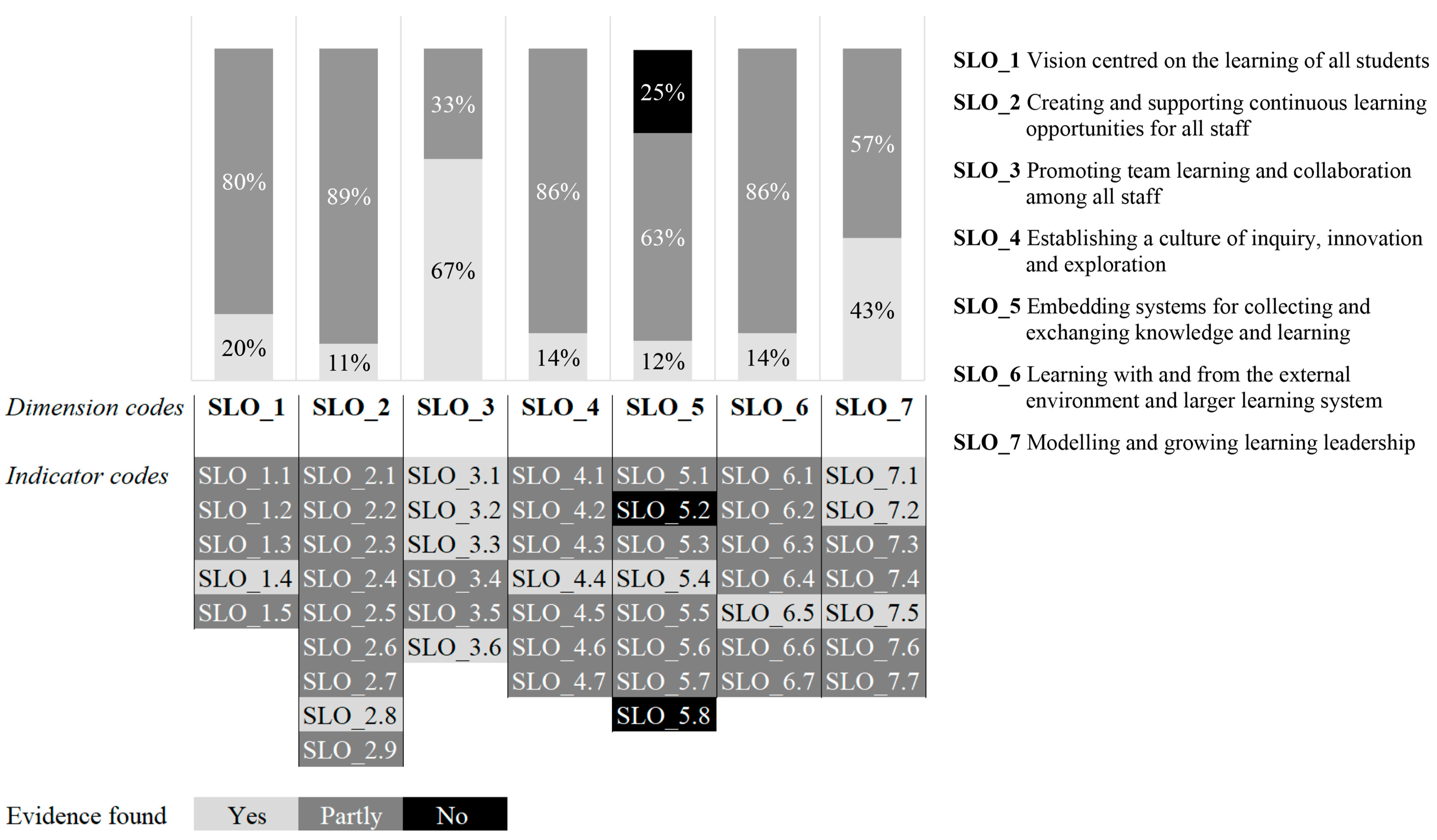

- The most evident is the understanding of performance indicators of SLO_3 (“Promoting team learning and collaboration among all staff”), followed by the understanding of resultative indicators of SLO_7 (“Modelling and growing learning leadership”).

- Less evident is the understanding of SLO_5 performance indicators (“Embedding systems for collecting and exchanging knowledge and learning”). There is no evidence regarding two resultative indicators, SLO_5.2 (“Examples of practice—good and bad—are made available to all staff to analyse”) and SLO_5.8 (“The school evaluates the impact of professional learning”).

- Moderately evident is the understanding of performance indicators of all other dimensions, e.g., SLO_1 (“Developing a shared vision centred on the learning of all students”), SLO_2 (“Creating and supporting continuous professional learning for all staff”), SLO_4 (“Establishing a culture of inquiry, exploration and innovation”) and SLO_6 (“Learning with and from the external environment and larger system”). There is evidence regarding four performance indicators, such as SLO_1.4 (“Vision is the outcome of a process involving all staff”), SLO_2.8 (“Time and other resources are provided to support professional learning”), SLO_4.4 (“Inquiry is used to establish and maintain a rhythm of learning, change and innovation”) and SLO_6.5 (“Staff collaborate, learn and exchange knowledge with peers in other schools through networks and/or school-to-school collaborations’’). Evidence was found partly regarding all other performance indicators of SLO_1, SLO_2, SLO_4 and SLO_6 dimensions.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kools, M.; Stoll, L. What Makes a School a Learning Organisation? A Guide for Policy Makers, School Leaders and Teachers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Building the Future of Education; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/future-of-education-brochure.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- UNESCO. Reimagining Our Future Together: A New Social Contract for Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379707.locale=en (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Reimers, F.M. In search of a twenty-first century education renaissance after a global pandemic. In Implementing Deeper Learning and 21st Education Reforms. Building an Education Renaissance after a Global Pandemic; Reimers, F.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincu, M. Why is school leadership key to transforming education? Structural and cultural assumptions for quality education in diverse contexts. Prospects 2022, 52, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Transforming Education: An Urgent Political Imperative for Our Collective Future. Transforming Education Summit 2022. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2022/09/sg_vision_statement_on_transforming_education.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Rotberg, I.C. Balancing Change and Tradition in Global Education Reform, 2nd ed.; Rowman & Littlefield Education: Lanham, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, C.R.V.; Giorn, G.; Arellano, I.; Bañuelos, A.A. The effects of educational reform. In Education in One World. Perspectives from Different Nations; Popov, I., Wolhuter, C., Almeida, P.A., Hilton, G., Ogunleye, J., Chigisheva, O., Eds.; Bulgarian Comparative Education Society: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2013; Volume 11, pp. 254–258. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. School Redesigned. Towards Innovative Learning Systems; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.; Dumont, H.; Lafuente, M.; Law, N. Understanding Innovative Pedagogies: Key Themes to Analyse New Approaches to Teaching and Learning; OECD Education Working Papers No. 172; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddie, A. School autonomy as ‘the way of the future’: Issues of equity, public purpose and moral leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2016, 44, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcia, G.; Demas, A. What Matters Most for School Autonomy and Accountability: A Framework Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/385451468172788612/pdf/What-matters-most-for-school-autonomy-and-accountability-a-framework-paper.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- OECD. Governing Education in a Complex World; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Activating Policy Levers for Education 2030: The Untapped Potential of Governance, School Leadership, and Monitoring and Evaluation Policies. UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265951 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Levin, B. Governments and education reform: Some lessons from the last 50 years. J. Educ. Policy 2010, 25, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, B.; Schneider, B.R. Managing the Politics of Quality Reforms in Education Policy Lessons from Global Experience; The International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://report.educationcommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Managing-the-Politics-of-Quality-Reforms.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Viñao, A. Do education reforms fail? A historian’s response. Encount. Theory Hist. Educ. 2001, 2, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kools, M.; Stoll, L.; George, B.; Steijn, B.; Bekkers, V.; Gouëdard, P. The school as a learning organisation: The concept and its measurement. Eur. J. Educ. 2020, 55, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.T.; Chan, D. A comparative study of Singapore’s school excellence model with Hong Kong’s school-based management. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2008, 22, 488–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tang, Y.; He, W.; Li, Q. Singapore’s school excellence model and student learning: Evidence from PISA 2012 and TALIS 2013. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2019, 39, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Developing Schools as Learning Organisations in Wales; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kools, M.; Gouëdard, P.; George, B.; Steijn, B.; Bekkers, V.; Stoll, L. The relationship between the school as a learning organisation and staff outcomes: A case study of Wales. Eur. J. Educ. 2019, 54, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Elder, Z.; Jones, M.S.; Cooze, A. Schools as learning organisations in Wales: Exploring the evidence. Wales J. Educ. 2022, 24, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, N.T. Building a learning organization in a public library. J. Libr. Adm. 2017, 57, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Teachers and School Leaders in Schools as Learning Organizations. Guiding Principles for Policy Development in School Education, 1st ed.; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://www.schooleducationgateway.eu/downloads/Governance/2018-wgs4-learning-organisations_en.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Ahmad, N.H.; Kudus, N.; Hassan, M.A. Schools as a learning organization: From the perspective of teachers and administrators. J. Contemp. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 2021, 1, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher, A. World Class: How to Build a 21st-Century School System; Strong Performers and Successful Reformers in Education; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torokoff, M.; Mets, T. Organisational learning: A concept for improving teachers’ competences in the Estonian school. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2008, 5, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pont, B.; Nusche, D.; Moorman, H. Improving School Leadership. Policy and Practice; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008; Volume 1, Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/school/Improving-school-leadership.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Hyler, M.E.; Gardner, M. Effective Teacher Professional Development; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poom-Valickis, K.; Eisenschmidt, E.; Leppiman, A. Creating and developing a collaborative and learning-centred school culture: Views of Estonian school leaders. Cent. Educ. Policy Stud. J. 2022, 2, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaki, N.; Owan, H. Autonomy, conformity and organizational learning. Adm. Sci. 2013, 3, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommarström, K.; Oikkonen, E.; Pihkala, T. The school and the teacher autonomy in the implementing process of entrepreneurship education curricula. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latvijas Republikas Ministru Kabinets. Par Izglītības Attīstības Pamatnostādnēm 2021–2027. Gadam. MK Rīkojums Nr. 436 [Regarding the Education Development Guidelines for 2021–2027. MK Order No. 436]. LR MK: Riga, Latvia, 2021. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/324332-par-izglitibas-attistibas-%20pamatnostadnem-20212027-gadam (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Latvijas Republikas Ministru Kabinets. Izglītības un Zinātnes Ministrijas Nolikums. MK Noteikumi Nr. 528 [Regulations of the Ministry of Education and Science. MK Regulation No. 528]. LR MK: Riga, Latvia, 2003. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/79100-izglitibas-un-zinatnes-ministrijas-nolikums (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Latvijas Republikas Ministru Kabinets. Izglītības Kvalitātes Valsts Dienesta Nolikums. MK Noteikumi Nr. 225 [Regulations of the State Service of Education Quality. MK Regulation No. 225]. LR MK: Riga, Latvia, 2013. Available online: https://likumi.lv/doc.php?id=256415 (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Latvijas Republikas Ministru Kabinets. Izglītības Iestāžu, Eksaminācijas Centru, Citu Izglītības Likumā Noteiktu Institūciju un Izglītības Programmu Akreditācijas un Izglītības Iestāžu Vadītāju Profesionālās Darbības Novērtēšanas Kārtība. MK Rīkojums Nr. 618 [The Procedure for the Accreditation of Educational Institutions, Examination Centers, Other Institutions and Educational Programs Specified in the Law on Education, and the Assessment of the Professional Performance of Educational Institution Managers. MK order No. 618]. LR MK: Riga, Latvia, 2020. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/317820-izglitibas-iestazu-eksaminacijas-centru-citu-izglitibas-likuma-noteiktu-instituciju-un-izglitibas-programmu-akreditacijas (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Latvijas Republikas Ministru Kabinets. Par Profesionālās Izglītības Administrācijas un Vispārējās Izglītības Kvalitātes Novērtēšanas Valsts Aģentūras Reorganizāciju. MK Rīkojums Nr. 356 [Regarding the Reorganization of the Vocational Education Administration and the State Agency for General Education Quality Assessment. MK Order No. 356]. LR MK: Riga, Latvia, 2009. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/192850-par-profesionalas-izglitibas-administracijas-un-visparejas-izglitibas-kvalitates-novertesanas-valsts-agenturas-reorganizaciju (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- VISC. Skola2030. Par Projektu [School2030. About the Project]. LR VISC: Riga, Latvia, 2018. Available online: https://www.skola2030.lv/lv/par-projektu (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- IKVD. Vadlīnijas Izglītības Kvalitātes Nodrošināšanai Vispārējā un Profesionālajā Izglītībā [Guidelines for Ensuring the Quality of Education in General and Professional Education]. IKVD: Riga, Latvia, 2020. Available online: https://www.ikvd.gov.lv/lv/akreditacija (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- VISC. Skola2030. Pārmaiņu Iemesli. [School2030. Reasons for Change]. LR VISC: Riga, Latvia, 2019. Available online: https://www.skola2030.lv/lv/macibu-saturs/macibu-satura-pilnveide/nepieciesamibas-pamatojums (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Latvijas Republikas Saeima. Par Latvijas Nacionālo Attīstības Plānu 2021–2027. Gadam [Regarding the Latvian National Development Plan for 2021–2027]. LR Saeima: Riga, Latvia, 2020. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/315879-par-latvijas-nacionalo-attistibas-planu-20212027-gadam-nap2027 (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Gilbert, G.N.; Stoneman, P. Researching Social Life, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, R.M. Passive bystanders or active participants? The dilemmas and social responsibilities of teachers. PRELAC J. 2005, 1, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, F.M. Thinking multidimensionally about ambitious educational change. In Audacious Education Purposes: How Governments Transform the Goals of Education Systems; Reimers, F.M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, H. Education reforms for equity and quality: An analysis from an educational ecosystem perspective with reference to Finnish educational transformations. Cent. Educ. Policy Stud. J. 2021, 11, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, G.A. Assessing the functioning of government schools as learning organizations. Cypriot J. Educ. Sci. 2021, 16, 1036–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.G.; Olivier, D.F. A quantitative study of schools as learning organizations: An examination of professional learning communities, teacher self-efficacy, and collective efficacy. Res. Issues Contemp. Educ. 2022, 7, 26–51. [Google Scholar]

- Coenen, L.; Schelfhout, W.; Hondeghem, A. Networked professional learning communities as means to Flemish secondary school leaders’ professional learning and well-being. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk, R.; Sezgin Nartgün, Ş. The relationship between teacher perceptions of distributed leadership and schools as learning organizations. Inter. J. Contemp. Educ. Res. 2019, 6, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Printy, M.S.; Marks, M.H. Shared leadership for teacher and student learning. Theory Pract. 2006, 45, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education Policy Outlook: Latvia; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/policy-outlook/country-profile-Latvia-2020.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Papazoglou, A.; Koutouzis, M. Schools as learning organisations in Greece: Measurement and first indications. Eur. J. Educ. 2020, 55, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Codes | Institution 1 | Institution 2 | Institution 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of Unique References (Coverage, %) | Count of Unique References (Coverage, %) | Count of Unique References (Coverage, %) | Count of Unique References | |

| SLO_1 (A shared vision centred on the learning of all students) | 5 (7.70) | 2 (0.60) | 2 (0.91) | 9 |

| SLO_2 (Continuous learning opportunities for all staff) | 12 (9.18) | 8 (5.14) | 1 (1.45) | 21 |

| SLO_3 (Team learning and collaboration among all staff) | 9 (9.51) | 16 (7.35) | 3 (2.92) | 28 |

| SLO_4 (A culture of inquiry, innovation and exploration) | 6 (6.02) | 3 (1.52) | 3 (1.79) | 12 |

| SLO_5 (Systems for collecting and exchanging knowledge and expertise) | 10 (7.13) | 1 (0.80) | 3 (1.58) | 14 |

| SLO_6 (Learning with and from the external environment) | 5 (2.26) | 14 (8.22) | 3 (1.44) | 22 |

| SLO_7 (Modelling and growing learning leadership) | 12 (10.86) | 14 (7.20) | 5 (6.66) | 31 |

| SLO_descript (The characteristics of the SLO) | 6 (7.36) | 7 (2.58) | 5 (7.26) | 18 |

| Dimension SLO_1 Performance Indicators (after [1] (p. 32)) | Institution 1 | Institution 2 | Institution 3 | Evidence Found |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | ||

| A shared and inclusive vision aims to enhance the learning experiences and outcomes of all students (SLO_1.1) | 4 (7.11) | - | - | Partly |

| The vision focuses on a broad range of learning outcomes, encompasses both the present and the future, and is inspiring and motivating (SLO_1.2) | 2 (1.30) | - | - | Partly |

| Learning and teaching are oriented towards realising the vision (SLO_1.3) | 1 (3.40) | 1 (0.14) | - | Partly |

| Vision is the outcome of a process involving all staff (SLO_1.4) | 1 (0.58) | 1 (0.47) | 1 (0.46) | Yes |

| Students, parents, the external community and other partners are invited to contribute to the school’s vision (SLO_1.5) | 1 (0.58) | - | 2 (0.91) | Partly |

| Count of unique references | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Dimension SLO_2 Performance Indicators (after [1] (p. 36)) | Institution 1 | Institution 2 | Institution 3 | Evidence Found |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | ||

| All staff engage in continuous professional learning (SLO_2.1) | - | 1 (0.31) | - | Partly |

| New staff receive induction and mentoring support (SLO_2.2) | - | 1 (1.31) | 1 (1.45) | Partly |

| Professional learning is focused on student learning and school goals (SLO_2.3) | 1 (0.69) | 2 (1.02) | - | Partly |

| Staff are fully engaged in identifying the aims and priorities for their own professional learning (SLO_2.4) | 2 (1.41) | 3 (2.82) | Partly | |

| Professional learning challenges thinking as part of changing practice (SLO_2.5) | 3 (0.86) | 1 (1.27) | - | Partly |

| Professional learning connects work-based learning and external expertise (SLO_2.6) | 6 (4.20) | 2 (0.37) | - | Partly |

| Professional learning is based on assessment and feedback (SLO_2.7) | 2 (0.63) | 1 (0.28) | - | Partly |

| Time and other resources are provided to support professional learning (SLO_2.8) | 1 (0.56) | 1 (1.31) | 1 (1.45) | Yes |

| The school’s culture promotes and supports professional learning (SLO_2.9) | 4 (3.51) | 1 (0.33) | - | Partly |

| Count of unique references | 12 | 8 | 1 |

| Dimension SLO_3 Performance Indicators (after [1] (p. 40)) | Institution 1 | Institution 2 | Institution 3 | Evidence Found |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | ||

| Staff learn how to work together as a team (SLO_3.1) | 3 (3.04) | 4 (1.29) | 1 (1.68) | Yes |

| Collaborative working and collective learning face-to-face and through ICTs are focused and enhance learning experiences and outcomes of students and/or staff practice (SLO_3.2) | 6 (6.53) | 7 (4.54) | 1 (0.65) | Yes |

| Staff feel comfortable turning to each other for consultation and advice (SLO_3.3) | 2 (2.06) | 1 (0.87) | 1 (0.60) | Yes |

| Trust and mutual respect are core values (SLO_3.4) | 1 (1.04) | 4 (0.83) | - | Partly |

| Staff reflect together on how to make their own learning more powerful (SLO_3.5) | 1 (0.22) | - | - | Partly |

| The school allocates time and other resources for collaborative working and collective learning (SLO_3.6) | 1 (0.36) | 2 (1.10) | 1 (0.65) | Yes |

| Count of unique references | 9 | 16 | 3 |

| Dimension SLO_4 Performance Indicators (after [1] (p. 45)) | Institution 1 | Institution 2 | Institution 3 | Evidence Found |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | ||

| Staff want and dare to experiment and innovate in their practice (SLO_4.1) | - | 1 (0.52) | 1 (1.04) | Partly |

| The school supports and recognises staff for taking initiative and risks (SLO_4.2) | 1 (0.57) | 1 (0.52) | - | Partly |

| Staff engage in forms of inquiry to investigate and extend their practice (SLO_4.3) | 2 (3.08) | 1 (0.29) | - | Partly |

| Inquiry is used to establish and maintain a rhythm of learning, change and innovation (SLO_4.4) | 1 (0.45) | 1 (0.70) | 2 (0.75) | Yes |

| Staff have open minds towards doing things differently (SLO_4.5) | - | 1 (0.29) | - | Partly |

| Problems and mistakes are seen as opportunities for learning (SLO_4.6) | 2 (2.12) | - | - | Partly |

| Students are actively engaged in inquiry (SLO_4.7) | 1 (0.38) | - | - | Partly |

| Count of unique references | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Dimension SLO_5 Performance Indicators (after [1] (p. 50)) | Institution 1 | Institution 2 | Institution 3 | Evidence Found |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | ||

| Systems are in place to examine progress and gaps between current and expected impact (SLO_5.1) | 1 (0.62) | - | - | Partly |

| Examples of practice—good and bad—are made available to all staff to analyse (SLO_5.2) | - | - | - | No |

| Sources of research evidence are readily available and easily accessed (SLO_5.3) | 1 (0.49) | - | - | Partly |

| Structures for regular dialogue and knowledge exchange are in place (SLO_5.4) | 4 (4.13) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.65) | Yes |

| Staff have the capacity to analyse and use multiple sources of data for feedback, including through ICT, to inform teaching and allocate resources (SLO_5.5) | 2 (1.43) | - | 1 (0.43) | Partly |

| The school development plan is evidence-informed, based on learning from self-assessment and updated regularly (SLO_5.6) | 3 (1.45) | - | 2 (0.94) | Partly |

| The school regularly evaluates its theories of action, amending and updating them as necessary (SLO_5.7) | 3 (1.07) | - | - | Partly |

| The school evaluates the impact of professional learning (SLO_5.8) | - | - | - | No |

| Count of unique references | 10 | 1 | 3 |

| Dimension SLO_6 Performance Indicators (after [1] (p. 54)) | Institution 1 | Institution 2 | Institution 3 | Evidence Found |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | ||

| The school scans its external environment to respond quickly to challenges and opportunities (SLO_6.1) | - | 4 (2.01) | 1 (0.31) | Partly |

| The school is an open system, welcoming approaches from potential external collaborators (SLO_6.2) | 1 (0.43) | 2 (1.16) | - | Partly |

| Partnerships are based on equality of relationships and opportunities for mutual learning (SLO_6.3) | - | - | 2 (1.13) | Partly |

| The school collaborates with parents/guardians and the community as partners in the education process and the organisation of the school (SLO_6.4) | 2 (0.71) | 2 (1.30) | - | Partly |

| Staff collaborate, learn and exchange knowledge with peers in other schools through networks and/or school-to-school collaborations (SLO_6.5) | 4 (1.97) | 3 (2.57) | 1 (0.69) | Yes |

| The school partners with higher education institutions, businesses and/or public or non-governmental organisations in efforts to deepen and extend learning (SLO_6.6) | 1 (0.43) | 5 (3.45) | - | Partly |

| ICT is widely used to facilitate communication, knowledge exchange and collaboration with the external environment (SLO_6.7) | - | 2 (1.00) | - | Partly |

| Count of unique references | 5 | 14 | 3 |

| Dimension SLO_7 Performance Indicators (after [1] (p. 58)) | Institution 1 | Institution 2 | Institution 3 | Evidence Found |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | Count of References (Coverage, %) | ||

| School leaders model learning leadership, distribute leadership and help grow other leaders, including students (SLO_7.1) | 1 (1.71) | 1 (0.86) | 2 (4.66) | Yes |

| School leaders are proactive and creative change agents (SLO_7.2) | 2 (0.68) | 6 (3.04) | 2 (0.82) | Yes |

| School leaders develop the culture, structures and conditions to facilitate professional dialogue, collaboration and knowledge exchange (SLO_7.3) | 5 (5.39) | 3 (1.59) | - | Partly |

| School leaders ensure that the organisation’s actions are consistent with its vision, goals and values (SLO_7.4) | 4 (5.28) | - | - | Partly |

| School leaders ensure the school is characterised by a “rhythm” of learning, change and innovation (SLO_7.5) | 1 (0.78) | 3 (1.84) | 2 (1.86) | Yes |

| School leaders promote and participate in strong collaboration with other schools, parents, the community, higher education institutions and other partners (SLO_7.6) | 1 (0.43) | 4 (2.01) | - | Partly |

| School leaders ensure an integrated approach to responding to students’ learning and other needs (SLO_7.7) | 2 (2.74) | 1 (0.42) | - | Partly |

| Count of unique references | 12 | 14 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siliņa-Jasjukeviča, G.; Lastovska, A.; Surikova, S.; Kaulēns, O.; Linde, I.; Lūsēna-Ezera, I. Education Policy Institutions’ Comprehension of the School as a Learning Organisation Approach: A Case Study of Latvia. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090907

Siliņa-Jasjukeviča G, Lastovska A, Surikova S, Kaulēns O, Linde I, Lūsēna-Ezera I. Education Policy Institutions’ Comprehension of the School as a Learning Organisation Approach: A Case Study of Latvia. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(9):907. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090907

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiliņa-Jasjukeviča, Gunta, Agnese Lastovska, Svetlana Surikova, Oskars Kaulēns, Inga Linde, and Inese Lūsēna-Ezera. 2023. "Education Policy Institutions’ Comprehension of the School as a Learning Organisation Approach: A Case Study of Latvia" Education Sciences 13, no. 9: 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090907

APA StyleSiliņa-Jasjukeviča, G., Lastovska, A., Surikova, S., Kaulēns, O., Linde, I., & Lūsēna-Ezera, I. (2023). Education Policy Institutions’ Comprehension of the School as a Learning Organisation Approach: A Case Study of Latvia. Education Sciences, 13(9), 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090907