Abstract

This study explores how assessment is presented in Swedish early years’ steering documents and considers risks for young gifted students in relation to assessment (or lack thereof). Document analysis was undertaken on, firstly, Swedish curriculum documents for the preschool and for the compulsory school, and secondly, mapping materials used in the preschool class with six-year-old children. Results show that assessment is not a term used in Swedish early years curricula. Instead, preschool teachers are asked to evaluate their own practice; preschool class teachers are asked to engage with mapping and only to consider working toward later assessment goals in year 3 of school. A plethora of alternative assessment terms are used in the curriculum without definition. Giftedness is also invisible in the curriculum. However, the mapping materials used with six-year-old students in the subject areas of mathematics and Swedish do encourage teachers to consider children who achieve mastery early. Further, these materials provide supportive questions and activities for teachers to use in exploring further. The specific examples of assessment discourses and the need to consider gifted children are combined in this article to highlight aspects of teacher work that are important for the educational rights of an often-forgotten group of learners.

1. Introduction

This article discusses the attention given to assessment and giftedness within early years’ steering documents in Sweden. The topic is important, as unless assessment is engaged with, recognition of children’s capabilities is likely to be at risk. The topics of assessment and giftedness have both been contested in the early years due to differing ideas about children’s rights, learning and teaching philosophies, and equality. The purpose of addressing these two contested areas in combination is to draw attention to the double risk of invisibility or misunderstandings regarding young gifted children in Sweden. We believe Sweden provides an interesting case study, being a context in which children’s rights are strongly articulated, yet there has not been a tradition of giftedness being recognised. Further, in Sweden, the interpretation of ‘assessment’ in the early years is oriented toward teacher self- and system-evaluation. The aims of the study are, firstly, to identify different ways that assessment is presented in early years’ steering documents and, secondly, to consider attention to giftedness in these documents. At the intersection of these issues is the consideration of children’s rights. We interpret assessment broadly as meaning to be noticed, recognised, and understood, and thus logically, children have the right to ‘have assessment or be assessed’ in the early years. From this assessment can come consideration of curriculum-connected learning opportunities, including appropriate stimulation and support. We begin with, firstly, a discussion of the early years context in Sweden—prior-to-school (preschool or early childhood), preschool class, and the early years of school. This frames the subsequent discussion of assessment in the early years in Sweden and, thirdly, the justification of how giftedness has relevance in the early years.

1.1. Context of Early Childhood Education in Sweden

Early childhood education in Sweden has a long history of paying attention to quality education and learning in the early years. This attention to quality ensures that children can attend stimulating and supportive early learning environments, that they have social and democratic experiences, and that parents can work with confidence in the quality of their children’s care and education. Early childhood services in Sweden are referred to by the Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE) as ‘preschools’, which is a direct translation of the Swedish word förskola. For this reason, in the rest of this article, the term ‘preschool’ will be used when referring to the specific context of Sweden, but early childhood education when referring to broader international contexts. The broader concept of ‘early years’ covers both early childhood (preschool) and the early years of school. Swedish preschools cater for children aged 1–5 years, are built on principles of quality learning environments, encourage children’s play and participation, and are led by a professional and qualified workforce. Sweden is a signatory party to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [1]. Article 29.1a of the convention states, ‘Parties agree that the education of the child shall be directed to the development of the child’s personality, talents, and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential’ (p. 9).

The concepts of ‘education’ and ‘care’ have been formally integrated since 1968 [2], and preschools have been managed by the same central agency as schools since 1996. Accessibility is important, with children having a guaranteed right to a place and fees being minimal. In the second half of 2022, 96% of five-year-olds attended Swedish preschools. Lower attendance rates of children younger than five are a reflection of the generous and universal paid parental leave of 480 working days, which can be ‘stretched’ over a longer period. The average attendance statistic is 86% of all children aged 1–5 years [3], varying in attendance between 15 and 40+ hours per week. The Swedish preschool curriculum was first published in 1998, then revised in 2010 and 2018 [4]. The curriculum stresses democracy from the very first sentence, as well as responsibility, citizenship, and attention to children’s rights.

In 1996, a new initiative was introduced in Sweden, entitled the ‘preschool class’ (forskoleklass), for children aged 6 years. This initiative aimed to provide a bridge between preschool and school. It became a universal right in 1998 and then compulsory in autumn 2018. In 2016, a curriculum for preschool class was included in the curriculum for the compulsory school [5], clarifying objectives for preschool class. Year levels 1 to 3, lower primary (lågstadiet), represent children across ages 7–9, often with the same teacher following the group all three years for continuity. A further feature of Swedish education is the provision of school-age educare (fritids), attended by the majority of children in preschool class and primary school, ensuring an integrated system of care and education across the day. Table 1 illustrates the parts of the Swedish school system that are in focus for this article and the corresponding curricula.

Table 1.

Swedish school system structure and curricula across ages 1–9 years.

The term ‘teacher’ is used for consistency throughout this article to acknowledge the pedagogical role of educational practitioners, regardless of which level of the education system they work in. Thus, the use of the term ‘teacher’ in this article embraces degree-qualified teachers as well as educators or pedagogues with lower-level qualifications.

1.2. Assessment’ in Early Years Education

Assessment is a contested term across all forms of early years education: early childhood (preschool), preschool class, and lower primary. The word ‘assess’ (bedömn) is not mentioned once in the Swedish preschool curriculum [6]. Yet, the Swedish preschool curriculum (2010) states that teaching should be mindful of children’s development and learning.

Commonly, early childhood resists normative, summative, or ‘schoolified’ approaches. Instead, formative, sociocultural, participatory, and agentic approaches are employed [7]. In Swedish, the translated word for assessment (bedömning)’ is most commonly understood as meaning the kind of assessment akin to testing and is firmly rejected by early childhood educators.

Sociocultural assessment starts from the assumption that the child has strengths and competencies that can be observed, documented, encouraged, and made more complex. Test-taking, ranking, scoring, and comparative judgments have questionable relevance, benefit, or ethical practice in everyday early childhood education. [7] (p. 5).

Åsén and Vallberg Roth [8] set out to document the diversity of approaches to documentation and assessment in Swedish preschools. Preschool teachers shared their use of pedagogical documentation and portfolios, individual development plans, evidence-based tools, and even standardised tools relating to such areas as language or social-emotional development. Åsén and Vallberg Roth concluded that the preschool teachers’ use of documentation in assessment supported them in following children’s development over time and that the development of each child’s skills and abilities remained in focus. Thus, their study shows that the absence of explicit curriculum text about assessment does not mean that assessment in the broad sense is absent in practice.

We authors draw on a broad interpretation of early childhood assessment in which it contributes an integral and valuable part of ‘robust’ early childhood teacher work—provided it is employed in context-specific and ethical ways with valid purpose [9]. We position assessment as part of supporting and understanding children and their learning. For example, a preschool teacher might observe that a child needs extra support with using utensils at lunch time, be aware of their favourite book and play preferences, or notice a prodigious memory and passionate interest in a particular topic. From these observations, a teacher can then plan how to give additional support or stimulation, working within the child’s zone of proximal development. The ‘right to be assessed’ so that an appropriate education can be provided is no different for gifted children than for other children. It can therefore be positioned as a social justice issue where gifted children are not recognised or receive an education appropriate for them.

A recent initiative on the Swedish assessment landscape is the 2019 introduction of mandatory assessment tools for use with six-year-olds within the preschool class. These tools—described as mapping (kartläggning) rather than assessing (bedömning)—support documentation of children’s mathematical thinking [10] and linguistic awareness [11]. The purpose of the mapping is to gather information that can support the teacher in identifying children who are in need of extra adaptations, special support, or extra challenges. This information and support can then be used to help children reach their individual potential. Nevertheless, there is debate as to the best use of teacher time, with Ackesjö [12] sharing the contention that ‘more assessment implies less teaching’ (p. 1). Walla’s research with Swedish and Norwegian assessment in mathematics for 6-year-olds [13] highlights the challenge of diverse perspectives in early years’ assessment. Walla notes ‘a diversity of discourses—both between and within the assessment materials—indicating different views on children’s learning [of mathematics], on when to assess, on what knowledge to assess, and on how and why to assess’ (abstract) [13].

This debate as to what form of assessment is appropriate and at what age continues across the school sector. In the compulsory school curriculum [14], goals are set for year levels 3, 6, and 9. Official grades are not given until the 6th year of school in Sweden, when children are 12 years of age. Prior to 2012, grades were first introduced in the 8th year of school (14-year-olds), and there is currently discussion of introducing grades in school year four (10-year-olds). One of the reasons provided for delaying the introduction of grades is stated to be that

Using official grades too early is considered detrimental since some children can be categorised and stigmatised. Young children are not yet fully aware of the difference between ‘I am’ and ‘I do’, and this can have a negative effect on the modelling of their selves.[2] (p. 7)

However, the exchange of observations and insights about children’s progress is particularly important for gifted children, as research indicates skills that parents have in identification [15] and that gifted children may ‘mask’ behaviour in schools and preschools [16]. We explore gifted issues in the next section.

1.3. Giftedness’ in Early Years’ Education

In practice, ’gifted education’ terminology can differ internationally; schools and early childhood settings can loosely use a wide range of terms: gifted, talented, highly able, exceptional, exceptionally able, high potential, high learning potential, precocious, bright, advanced, and highly advanced. There can also be an absence of any reference to giftedness, especially in early childhood. The Swedish National Agency for Education notes that approximately 5% of students in Swedish schools are potentially gifted. However, no standard measure or process for identification is given, nor is there a definition of what giftedness means [17]. As Ivarsson writes:

On the one hand, giftedness is described in different ways and has different starting points, which can make the interpretation and understanding of the concept difficult. On the other hand, it can be seen as a strength that giftedness can be understood and viewed in several different ways.[18] (p. 1)

As with the term assessment, the term ‘giftedness’ and associated synonyms are contested within Sweden and within the Swedish curriculum. A consequence, according to Ivarsson, is that “[e]ven though we in Sweden have “a school for all”, gifted students have ended up in the shadows, with no or little attention.” [18] (p. 2).

‘Giftedness’ can be understood in differing ways, according to a multitude of differing theorists. Historically, research focused on conservative single-criterion approaches such as IQ measurement. More contemporary approaches have included multi-categorical perspectives, including such domains as intellectual, creative, social, perceptual, and physical [19], and moral and ethical [20]. Multi-categorical perspectives align more easily with early childhood, within which learning is commonly integrated and holistic and ‘the whole child’ is recognised. For Renzulli [21], giftedness is defined as the nexus of above-average abilities, task commitment, and creativity. At very young ages, one can see evidence of these three aspects being more developed in some children.

Gagné’s [19] differentiated model of giftedness and talent (DMGT) is especially useful for the early years, as he differentiates between hereditary giftedness and talent that has been developed over time. Think of a young child who shows strong and early musical responsiveness by bopping to music in the pram, drumming their fingers to tunes or conducting rhythmically, singing rather than speaking, and recognising portions of classical music. For such a child, support and extension can be offered regardless of any specific testing of their ‘musical giftedness’ or even any kind of decision about whether they are gifted or not. Perhaps this musically engaged child might enjoy being exposed to music and dance from differing cultures, learning an instrument, using song in pretend play, learning to read music, or performing a small concert. Teachers are likely to be mindful of not pressuring children to ‘perform’, and to consider their developmental trajectory. For example, Angela passionately enjoyed learning piano and reading musical scores at four years old but became frustrated that her fingers could not physically do what her brain had mastered. Returning to the DMGT model [19], we can suggest that a musically gifted child might develop into a talented individual in time and with the support of context/environment, catalysts, and their own motivation and volition. In Angela’s case, as an older child and young adult, she participated in many orchestras, completed a music degree, and composed her own music.

Teachers play an important role in the early identification of potential giftedness and in providing opportunities for the development of talent. Author 1 [22] suggested that it is important for teachers to support potentially gifted children by utilising both ‘general’ teaching strategies, which benefit all children, and ‘specific gifted education’ teaching strategies. As with all children, potentially gifted children are unlikely to thrive without a supportive environment, recognition of their potential, or opportunities for stimulation. Teachers can enrich the learning environment with open-ended questions, resources, and activities in the early years. They can also use resources from above-level expectations, differentiation, programs, enrichment activities, or content acceleration. Teachers can also be mindful of common (but not universal) characteristics of potential giftedness: insatiable questioning, exceptional memory, intense observation, problem-solving, early reading and calculation skills, and creative thinking [23]. Author 1 shared an example of creative planning and play from 4-year-old Xavier in a New Zealand early childhood centre. This example is included to show that a play-based, child-centred orientation to learning is supported in the early childhood sector:

Xavier (4:08) applied his knowledge about space in creative ways through drama. In one early child-hood education service other children did not want to join in with a game he created about planets, but he was able to involve others in a specific children’s drama group. The following commentary describes his play: ‘There are 10 people in the play, one for each planet, and I’m including Pluto, even though it’s a dwarf planet. One person has to be the sun, but they don’t get to move, because the other people will be orbiting around them. Everybody in the play will be wearing hula hoops of different colours, the same as the planets, so the people not in the play will know which planet is which and we will sing my planet’s song.’ This narrative also shows Xavier’s awareness of others: both the participants in the play and the audience.[23,24] (p. 35)

The opportunity for parents and early childhood teachers to share insights about a child is important in early childhood education. For gifted children, this can be especially important, as even very young children can mask their ability in certain situations, such as when they feel different from others or have concurrent learning disabilities [25]. It is also important in a context where teachers have a limited understanding of giftedness. A case study by the authors illustrates preschool teacher and parent collective support in the context of a young Swedish child ready for more advanced mathematics [26].

An absence of explicit reference to giftedness and gifted children in five international early childhood curricula and two wider policy texts, including the 2010 Swedish preschool curriculum, was documented by Margrain and Lundqvist [6]. However, their analysis also identified a great deal of implicit attention and support for gifted children in the curriculum text, which gives a mandate to teachers to respond. For example, Swedish curricula indicate that education should build on the children’s previous knowledge and experience, provide continuous challenge and new discoveries and knowledge, and give additional support and stimulation to the children who need it [4,14]. Examples of word-level Swedish preschool curriculum text that could be seen as aligning with implicit gifted education policy include the following terms and number of times mentioned: develop (103), learn (56), ability (35), stimulate (17), challenge (9), and equity (9) [6]. These terms all provide scope for teachers to identify a policy mandate to attend to the needs of gifted children within the framework of democratic, equitable education for all children.

1.4. Aim of This Research

In Swedish early years’ education policy, assessment and giftedness are contested terms, yet at the same time, children are supposed to be challenged and supported from the start. Therefore, we are interested to see in what ways the steering documents support/enable teachers to recognise and respond to children and their learning potential. The following research questions will guide us in our document study:

- How is assessment (broadly understood in all forms and through alternative terminology) presented in Swedish early years’ steering documents?

- In what way is attention to giftedness explicitly and implicitly given in the steering documents for early years’ education (in relation to a mandate for assessment practice)?

From these two questions, we aim to highlight considerations at the intersection of the two issues, in particular where steering documents lack visibility and where there are explicit examples to indicate action. Teachers, researchers, and policymakers continue to consider quality care and education for young children, as well as children’s rights. By drawing attention to young gifted children and related assessment perspectives, the needs of this often-forgotten and therefore at-risk group can be profiled within these considerations of quality and children’s rights.

2. Materials and Methods

In this section, we share our methodology and research positioning, a description of our document analysis method, and an overview of the data. We also give attention to ethical research issues.

2.1. Methodology and Research Positioning

This research draws upon a hermeneutical paradigm through its use of textual interpretation, or, in other words, finding meaning in the written word [27]. Assumptions underlying hermeneutics include the recognition that humans experience the world through language and that this engagement with language/text supports the development of understanding and knowledge. A hermeneutical perspective is relevant to our study because our method involves text analysis of steering documents. We engage with hermeneutical meaning-making and reflection on values espoused relating to assessment work and to giftedness (explicitly and implicitly). Becoming aware of the differing potential meanings of concepts such as assessment or attitudes toward giftedness can support important discussion and reflection on both education policy and teacher practice.

2.2. Method

The research method employed is document analysis [28]. Following the stepwise procedure outlined below, two types of steering documents were analysed by reading and marking downloaded PDF files. Firstly, a curriculum analysis was employed for the Swedish preschool curriculum [4] and lower primary school [14], and secondly, an analysis of mapping materials used in preschool class for the subjects mathematics [10,29,30,31,32] and Swedish language arts [11,33,34,35,36]. The stepwise procedure meant that key statements were identified (step 1) and key terms could be identified (step 2). Giftedness was not analysed in the curriculum documents, as this had already been analysed in a previous publication [6].

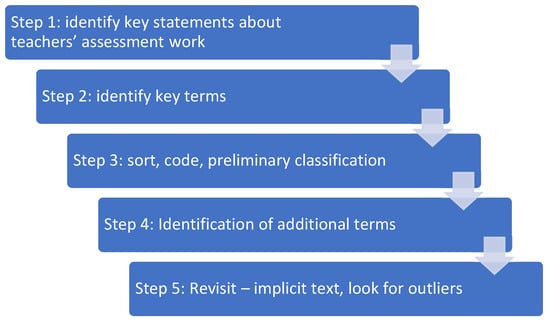

For the curriculum analysis, the whole procedure started with identifying key statements about teachers’ ‘assessment work’ in the two curricula of relevance for this study: the curricula for preschool [4] and the curriculum for preschool class and compulsory school [14]. Key terms were then identified, and through a sorting and coding procedure, a preliminary classification was made, after which additional terms were added if appropriate and the data was revisited (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Curriculum document analysis process (preschool curriculum + compulsory school, preschool class, and school-age educare curriculum).

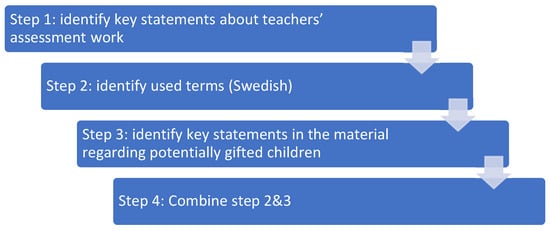

For the mapping materials—which are specific to preschool class—[10,11,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], the material was analysed regarding both assessment and giftedness, and a similar process as for the curriculum analysis was adopted (see Figure 2). Giftedness was included in this analysis as the preschool class mapping materials had not been studied in the Margrain and Lundqvist study [6].

Figure 2.

Mapping materials and document analysis process (preschool class).

During this process, several cross-checks were conducted where the authors shared their findings with each other and discussed differences, interesting or challenging cases, and other points of interest.

2.3. Data

The data used in this study are, firstly, the curriculum for preschool [4], and the curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class, and school-age educare [14] (with attention to lower primary school and preschool class). The newest, revised curricula were used. Secondly, we analysed the mapping materials provided by the SNAE [10,11,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] for use in preschool class. These documents were chosen as they are the only compulsory documents provided for teachers within this age group.

The preschool curriculum [4] consists of two parts: one part focusing on the fundamental values and tasks of the preschool (Förskolans värdegrund och uppdrag, 7 pages) and one part in which general goals and guidelines are set out (Mål och riktlinjer, 9 pages). The curriculum for preschool class is included in the curricula for the compulsory school [14] and consists of three parts: one part focusing on the fundamental values and tasks of the preschool class (Förskolans värdegrund och uppdrag, 6 pages), one part in which general goals and guidelines are set out (Mål och riktlinjer, 10 pages), and one part specifically for preschool class (4 pages). The curriculum for compulsory school consists of 230 pages, of which 57 are relevant for lower primary school and thus included in our data.

The mapping materials focus on mathematics (Hitta matematiken [10,29,30,31,32] and Swedish language arts (Hitta språket) [11,33,34,35,36]. These mapping materials are provided online. For both language and mathematics, the material consists of a general text about the material and four activities described in detail with introductory texts to each activity (53 pages in total). The topics covered in the mapping materials for mathematics are patterns [29], number sense [30], measurement [31], and spatial awareness [32]. For the Swedish language arts, the topics are: telling and explaining [33], listening and conversation [34], communicating with symbols and letters [35], and distinguishing words and sounds [36]. The materials are to be used in preschool class according to the school regulation; Chapter 8, Section 2 of the 2010 school regulation [37] states that from July 2011, national mapping materials must be used to map children’s linguistic awareness and mathematical thinking in preschool class. The aim is to support teachers in identifying children who are in need of extra adaptations, special support, or extra challenges to reach as far as possible. Due to a new curriculum, the mapping materials were revised in 2022, and the term ‘knowledge requirements’ (kunskapskrav) was replaced with the term ’criteria for assessment’ (kriterier för bedömning av kunskaper).

2.4. Ethical Research

No human participants were engaged in this research; the research involved the analysis of publicly available curriculum and related documents, which were openly downloadable from the internet. Therefore, no formal ethical application was required. However, the ethical guidelines of the Swedish Research Council were followed [38]. Particular ethical issues include attention to trustworthiness, accurate reporting, beneficence, and avoiding harm. As two researchers, we were able to share our analyses with each other as a form of accountability. While we may highlight areas that lack visibility or clarity, we also recognise that the curriculum is complex and often specifically designed to allow for diverse interpretations. In this way, our choice of hermeneutical meaning-making perspective is relevant. Nevertheless, the findings of our study are to be treated with care, and complexity should be included in the communication of our findings. We acknowledge that highlighting the absence of explicit attention to assessment and giftedness can be used for negative purposes, but our intention is rather to highlight positive possibilities and the inclusion of alternative discourses.

3. Results

In line with the process of the analysis, we first report on the findings from the analysis of assessment texts in the Swedish preschool curriculum, then follow with assessment texts in the Swedish curriculum for preschool class and compulsory school. These two curriculum sections are then followed by the findings from the analysis of the mapping materials (Kartläggningsmaterialet) used in Swedish preschool class.

3.1. Assessment Text in the Curriculum for Swedish Preschool

A curriculum citation from the Swedish preschool curriculum [4] that includes many terms aligned to assessment work is cited below (despite the absence of ‘assessment’ as an explicit term), with emphasis added by ourselves to highlight these terms. The citation led to us exploring the further use of the highlighted terms and a close reading of the full curriculum to identify other potential terms.

Preschool teachers are responsible for: …

• each child’s development and learning being continuously and systematically followed, documented and analysed so that it is possible to evaluate how the preschool provides opportunities for children to develop and learn in accordance with the goals of the curriculum,

• documentation, follow-up, evaluation and analysis covering how the goals of the curriculum are integrated with each other and form a whole in the education,

• carrying out a critical examination to ensure that the evaluation methods used are based on the fun-damental values and intentions as set out in the curriculum,

• results from follow-ups and evaluations systematically and continuously being analysed in order to develop the quality of the preschool and thus the opportunities of children for care, as well as con-ditions for development and learning, and

• using the analysis to take action to improve education.(pp. 19–20. emphasis added)

The citation above has potential terms connected to assessment, which we have highlighted in bold. This text is one key example that supported us in constructing a list of potential search words that could be broadly connected to assessment activity. These search words were: analyse, archive, document, examine, evaluate, follow (including follow-up and follow-up), investigate, and monitor. The Swedish preschool curriculum document [4] was then interrogated for mentions of these and other terms. In total, we identified 51 word-level mentions that could be connected to assessment activity, despite there being no explicit use of the word ‘assessment’, as shown in Table 2. An analysis of the full-text meaning of the relevant sentences from which these words came highlighted that the predominant ‘assessment’ work of Swedish preschool teachers in the curriculum is to evaluate. The evaluation activity was described in the curriculum as being an evaluation of the teachers’ own practice and the system within which they worked. By comparison, there was considerably less emphasis given to assessment of or for children’s learning or for helping children to self-assess or evaluate, even though supporting children’s agency is promoted. Even less attention is given to caregivers’ roles in ‘assessment’ processes, even though parent-teacher partnership is highlighted often throughout the curriculum. The activity of documentation was not explicitly connected to caregivers—only to teachers and children. There were no mentions of assessments connected to the work of preschool principals, which is a difference from our later analysis of the compulsory school curriculum.

Table 2.

Word-level ‘assessment’ mentions in Swedish preschool curriculum.

A review of the text also highlighted that references to assessment-related terms often occurred simultaneously within the same sentence within the preschool curriculum [4]. However, there were no definitions, explanations of differences between the similar terms, or clarifications as to why the order is important. Across pages 19–20, the following phrase citations illustrate the grouping of ‘assessment’ terms within sentences:

• Continuously and systematically follow, document and analyse

• Systematically and continuously document, monitor, evaluate and analyse

• Documentation, follow-up, evaluation and analysis[4], (pp. 19–20)

Different aspects of assessment are described in these terms. In the first example (systematically follow, document and analyse), the element of evaluation is not included, yet it is included in the second and third examples, pointing to formative aspects of assessment. We further noticed differences between the use of follow, follow-up, and follow-up, again without explanation as to whether there was any important distinction between these variations.

Although we did not undertake data analysis on text around giftedness since this had already been done [6], we could identify Swedish preschool curriculum text content that connected our new research analysis of assessment discourse with an implicit connection to gifted education. For example, the text highlights the importance of challenge, stimulation, and special support and that some children have a right to an education that is adapted to their individual needs. The Swedish preschool curriculum [4] states that the purpose of education is to:

… continuously challenge children by inspiring them to make new discoveries and acquire new knowledge. The preschool should pay particular attention to children who need more guidance and stimulation or special support for various reasons. All children should receive an education that is designed and adapted so that they develop as far as possible. Children who need more support and stimulation, either temporarily or permanently, should be provided with this, structured according to their own needs and conditions.(p. 7)

So, if preschool should ‘pay particular attention’ to children who have individual learning needs, surely that mandates some form of assessment activity? In the next section, we explore how discourses continue or shift in the early years of the compulsory school sector.

3.2. Assessment Text in the Curriculum for Swedish Preschool Class and Compulsory Schools

In 2022, the Swedish Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class, and school-age educare [14]—hereafter referred to as the compulsory school curriculum but inclusive of preschool class—was revised. A major shift is noticeable when comparing the previous and current compulsory curriculum documents with regard to the word assessment. A comparison shows that the word assessment (bedöma, bedömas, bedömning, bedömningar, bedöms) was mentioned 10 times in the compulsory school curriculum of 2011 (revised 2018) and substantively increased the number of mentions to 176 times in the revised compulsory school curriculum of 2022. Not all 176 words are actually describing a practice of assessment (some might be headings, used as a synonym to ‘is considered’, or are related to content-specific goals such as reasonableness assessment for estimates and calculations (Rimlighetsbedömning vid uppskattningar och beräkningar, p. 55). In 137 of these instances, assessment is related to assessment criteria for children ages 12–16 years and thus not within the scope of this study. Of the remaining, only a few describe a practice of assessment relevant for children ages 6–9 years.

In the section describing goals and guidelines for ages 6–16 years (Övergripande mål och riktlinjer, 10 pages), assessment is mentioned twice in relation to what a child is supposed to do, as shown in bold in the text below:

The school’s goal is that every child develops the ability to self-assess their results and relate their own and others’ assessment to one’s own work performance and conditions.[14] (translated, p. 18, emphasis added)

Self-assessment and assessment of others are two specific assessment situations that are put forward in the school curriculum for children ages 6–16. Further, assessment is mentioned twice in relation to teacher reporting and grading, as shown in bold in the text below:

• “based on the syllabus requirements, comprehensively evaluate each child’s knowledge development, report this orally and in writing to the child and the homes, and inform the principal;

• make an all-round assessment of the child’s knowledge in relation to the national grading criteria”.[14] (translated, p. 18, emphasis added)

There is thus a shift in how evaluation is understood in the school curriculum, with the school sector including evaluation as being of and with children. This is a shift from the preschool sector, where evaluation was understood as of the teacher’s own work and system-level evaluation. The citations below indicate that teachers are expected to evaluate and make an all-round assessment of the children’s knowledge. Further, teachers are expected to plan and evaluate teaching together with the children:

Teachers should: “[…] together with the children, plan and evaluate the teaching# [14] (translated, p. 18, emphasis added).

With a focus on the principal, the compulsory school curriculum [14] states that the principal at the school has a responsibility to follow up on grades in relation to assessment criteria. At the school level, results need to be followed up and evaluated in “active collaboration with the school’s staff and children and in close cooperation with both homes and with the surrounding community” (p. 10, translated). This follow-up with caregivers has specific references to assessment, grading, and evaluation, which differ from the preschool curriculum.

With specific reference to the preschool class, teachers are to take the criteria for assessment for later years into account, but there are no criteria defined until year level 3. Only one instance of an alternative ‘assessment’ word (evaluate, utvärdera—p. 18) was found in the curriculum for preschool class. All together, this means that the practice of assessment—with specific relevance to children aged 6–9 years—is only mentioned nine times in the compulsory school curriculum.

3.3. Mapping Materials (Kartläggningsmaterialet) for the Swedish Preschool Class

Connected to a practice of assessment, our examination of the mapping materials [10,11,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] led to the identification of the key words. To start with, the material is called ‘mapping material’ (kartläggningsmaterialet), and the word mapping (kartläggning) is frequently used in different variances. Other terms used are: identify, notice (få syn på), pay attention to, and observation points. Further, assessment is used in relation to the criteria described for year-level 3.

As for the analysis regarding giftedness, the mapping materials have a specific section in the activities that addresses not only how children who have progressed further can be detected (see Table 2) but also the needs they have in their knowledge development. We acknowledge that ‘children who have progressed further’ are not necessarily gifted, but it is nevertheless of consequence that attention is given to this group of children. The materials provide alternative questions for teachers to ask or alternative tasks to offer for the students who have progressed further. Such attention to those who have progressed further or who learn more rapidly is novel in Swedish teacher resource material. The activities follow a specific structure, and the same words and wordings are used in all activities, as indicated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Guidance for attention to children who have progressed further in preschool class mapping materials.

‘To notice children who have progressed further’ is explained in relation to the specific topics within the mapping materials. An example: The mathematical activity ’playground’ deals with the mathematical concept of spatial awareness. The child’s curiosity and interest in the mathematical content of the activity, the child’s ability to try and use different ideas, and the child’s communication and reasoning regarding space, perspective, and time are assessed.

The following examples are given in relation to how children who have progressed further will show their competence:

• “in their strategy take into account colour, shape, size, and direction of the images;

• explain why one place fits better than another;

• communicate in a way that leads problem solving further, and/or;

• reason and communicate about what season it is and why it is that season”.[32] (translated, p. 4)

When a teacher has identified a child who has progressed further, the mapping material gives suggestions for alternative questions that can be asked of such a child. In the same activity, Playground [32], the following suggestions for alternative questions are given:

• “How do you know that particular picture card shows what the girl sees?

• How do you know that location is incorrect?

• How do you know she’s not standing there?

• How can one know what season it is?”[32] (translated, p. 3)

Potential giftedness is mentioned in relation to children’s mathematical behaviour and language skills. In the example above, we can see a difference between mathematical behaviour (for example, ‘communicate in a way that leads problem solving further’) and mathematical skills (for example, ‘in their strategy, take into account colour, shape, size, and direction of the images’). Giftedness can thus be connected both to specific mathematical content and to a child’s mathematical behaviour. Similar examples can be found in the mapping materials for language, like in the first activity, “we tell and describe”:

The child is able to describe a phenomenon or thing in several stages and is able to actively participate in conversations, invite others to conversations, and listen to others.[33] (translated, p. 5)

In summary and as a short answer to our research questions, assessment (bedömning) is not used explicitly, but alternative terminology is used, and through that, different aspects of an assessment practice are apparent in Swedish early years’ steering documents. However, there is a different emphasis on particular words at different levels of the system, differing interpretations of the same terms, and a lack of definition of terms. Giftedness is not mentioned in the curricula, but in the mapping materials, explicit statements regarding children who have progressed further are found, including instructions for the identification of such children and suitable follow-up. In the next section, we will relate these findings to the aim of our study and describe in what way the steering documents support/enable teachers to recognise and respond to children and their learning potential.

4. Discussion

In this discussion, we return to our research questions and consider, first, assessment texts in the early years and, second, the specific context of assessment for young gifted children. Thirdly, we take up rights-based implications, including the risk of neglecting assessment for this group, and conclude with possibilities for the future.

4.1. Assessment Text in the Early Years

The word- and phrase-level analysis of the early childhood curriculum (Section 3.1) leads us to reflect on the finding that the majority (31 of 52 mentions) focus on teachers’ evaluation of their own practice (as opposed to assessment of and for children). Of course, professional self- and peer-evaluation is important, and care should be taken to avoid prematurely or negatively labelling children. Nevertheless, the minimal attention to assessment of and for children might obstruct teachers’ attention to the identification of children’s strengths and needs and the establishment of children’s zones of proximal development. What does it mean for early intervention when the focus of evaluative-assessment work is on the system, not children or the individual child? Further, if we reflect on the earlier research by Åsén and Vallberg Roth [8]—and our wider knowledge of early childhood teacher work—we are aware that there is substantive ‘assessment work’ of and for learning in early childhood that is invisible within the curriculum. What does it mean when important work is invisible and potentially seen as taboo to talk about? This nature of the taboo and discomfort with the terminology of assessment can be explored further in ongoing research.

We further wonder: do teachers have clarity as to the difference between the terms evaluation and analysis, and why in the curriculum text are teachers sometimes asked to evaluate before analysing and otherwise just analyse? There is a substantive difference between following up and then documenting vs. documenting and then following up—was this change in text deliberate or accidental, and do teachers notice this shift? Without definition, we also wonder about the subtleties of the difference between following and systematically following; documenting and systematically documenting; and examination and critical examination. These questions are beyond the scope of this article and need follow-up in further research, potentially interview-based.

For the Swedish curriculum for preschool class and compulsory school [14], assessment first seems to be more explicitly present, with almost 180 mentions. However, a closer look reveals that only a few of these instances are related to the practice of assessment of or for children, and none are specifically stated in the section for the preschool class. As with the curriculum for preschool, assessment is often presented in terms of the evaluative-assessment work of the system and teacher practice. Therefore, many of the same reflections we pose regarding the clarity of assessment work in preschool continue on into the context of preschool class and the early years of school.

We also found it curious that, despite strong encouragement for preschool teachers to work in partnership with caregivers, there was limited acknowledgement of the contribution that caregivers make to the assessment process. In particular, there were no mentions of the activity ‘document’ connected to caregivers, despite the fact that many families have extensive photographic or portfolio documentation of children’s milestones, early writing, art, and so forth. We suspect that this issue, like others, might indicate a difference between policy text and actual practice. There is an opportunity to make parent-teacher assessment sharing more visible in policy documentation and guidelines. Nevertheless, documentation sharing can, of course—and we hope it does—occur whether it is explicitly stated in policy.

Our summary of discourse is that there is a shift in focus and terms used across the three system levels we examined. Firstly, evaluation was in focus for preschool, then mapping became in focus in preschool class, and finally, some limited mentions of assessment were made in year level 3 of compulsory school (see Table 4). Discussion of these shifts needs to be well understood by all involved if they are to understand the differing nature of assessment. It is definitely much more complex than to simply say, ‘we don’t do assessment in Swedish preschool’.

Table 4.

Discourse shifts of assessment and giftedness across Swedish preschool, preschool class, and lower primary.

4.2. Assessment of Young Gifted Children

With regard to giftedness, the preschool curriculum has no specific mentions, and the curriculum for preschool class and compulsory school only mentions these children implicitly (see Table 3). With invisibility in policy comes the risk of being overlooked in practice. However, the mapping material stands out positively because of explicit mentions and guidelines on how to notice and detect children who have progressed further (see also Table 3). Teachers are encouraged to assess, map, notice, and evaluate specific competencies and skills. We find the mapping materials provide useful guidance for teachers and serve a positive purpose. Such careful observation and practical follow-up support children’s learning and potential identification.

For young gifted children, the opportunity for caregivers to share family documentation can also be especially useful in providing evidence of competencies that a child might mask or hide in preschool and school. This may be especially important in the early years, when schools do not have other potential identification tools in place.

In the absence of any definition, there will likely continue to be confusion as to whether students are high achievers, have high learning potential, are potentially gifted, or are gifted. However, alongside lamenting invisibility in the curriculum, we can celebrate what does exist. There are online resources on giftedness provided by the Swedish National Agency for Education, and there is an increasing interest in Nordic gifted education research. This is evidenced by increasing publications, doctoral student research, a Nordic research network, teacher professional development opportunities, municipality networks, and parent networks. Such initiatives can be harnessed to support gifted education in the field, for example, by sharing resources and strategies.

Among the analyses conducted in this article, the mapping materials stand out positively as explicitly attending to children ‘who have progressed further’. Of course, we can debate what that description means, who is included and excluded, and the dangers of a normative approach (progressed further than whom?). However, using a broad concept such as ‘children who have progressed further’ is better than having no consideration or mention at all of those who would benefit from program differentiation. The point is, surely, that (regardless of term), we are alert to children’s competence and potential and that teachers use whatever tools possible to understand children’s learning needs. Then we can follow the equally important next step, which is program differentiation and opportunities for new learning.

4.3. Rights, Risks, and Possibilities

This article began with consideration of the assessment of young gifted children and the risk to them of invisibility in policy document text. In Sweden, where gifted children are in ‘regular’ class, every teacher is potentially a teacher of gifted children and engages with gifted education. Therefore, attention to gifted children in Swedish preschools and schools is inextricably linked with attention to teachers’ everyday classroom work. If Sweden is, as claimed, ‘a school for all’, then it cannot continue to be that gifted children—or any other group of children—are invisible in policy or practice. There are therefore important opportunities to apply this analysis to wider international contexts where inclusive practice is articulated as an ambition. Does ‘inclusion’ include all children, in particular gifted children? And what exactly are they included in: in the physical classroom or in opportunities to learn? And do assessment practices—whether formal or not—ensure that teachers can recognise all gifted students? How are we doing with those from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds or whose domain of giftedness is something other than academic? These are questions of international interest for all education systems to reflect on.

The implication of our text analysis is that there is a double risk impacting young gifted children. Firstly, they miss being recognised due to the invisibility of both giftedness discourse and assessment discourses of or for children’s learning. Secondly, this lack of recognition can present a risk to these children’s democratic right to an appropriate education adapted to their learning level. Children’s rights are more than simply attending or being present in school or preschool. The UN Convention [1] states that they have the right to an education—that is, they have the right to opportunities to learn.

Opportunities for further research are many. It is important to move beyond the policy text and see how this curriculum is implemented in reality with regard to assessment and giftedness. As noted earlier, the absence of policy text does not mean the absence of practice. Interviews might explore in what way teachers make sense of the terms used in steering documents and the instructions provided in mapping materials. Interviews would also explore how teachers notice and respond to gifted children and their interactions with parents. Observations and analysis of planning might explore how teachers follow and follow-up gifted children and what questions are asked of children who have progressed further. Through an observational or interview study, the enacted curriculum can be in focus, and the children themselves can express their lived experience of assessment and giftedness. This is important so that research is not only ‘on’ children but also engages their perspective. Ensuring children’s voices are heard leads to respect for their educational rights and an important opportunity to analyse policy enactment by those who are affected. We also have an interest in engaging in international comparative analysis of steering documents to be able to share how assessment and giftedness in the early years are framed in diverse countries.

So, what are our recommendations for policy and practice? Further discussion is needed on the collective understanding of assessment activity—taking up assessment in the broadest possible definition, including the activities that we know do occur in preschools, preschool class, and schools: observation, discussions, formative assessment, anecdotal note-taking, and pedagogical documentation. Without these discussions, challenges exist for potential common understandings of assessment practices and processes (including differing definitions and discourses), appreciation for teachers’ work, collaboration across school sectors and with caregivers, and the work of early identification. We suggest acknowledgment that assessment is an already existing practice in the early years, used in the context of supporting children’s learning. Simultaneously, we recommend sharing examples of gifted children at all levels of the education system and positive examples of teachers’ work with these children. Such examples should include diverse and age-appropriate assessment approaches and follow-up on the assessment results. Further, we recommend sharing examples of giftedness and learning support beyond formal education, especially from caregivers. For both assessment and giftedness considerations, we hope that the examples we share in this article can add to professional learning discussions and reflections that lead to questions about explicit and implicit policy. While responsive practice can supersede policy, the text of steering documents sends a message about what is important, what policy text is not, and what is. Policy clarifications, such as definitions and attention to at-risk or marginalised groups, would be useful future actions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M. and J.v.B.; methodology, V.M. and J.v.B.; software, not applicable; validation, V.M. and J.v.B.; formal analysis, V.M. and J.v.B.; investigation, V.M. and J.v.B.; resources, V.M. and J.v.B.; data curation, V.M. and J.v.B.; writing—original draft preparation, V.M. and J.v.B.; writing—review and editing, V.M. and J.v.B.; visualization, V.M. and J.v.B.; supervision, not applicable; project administration, V.M. and J.v.B.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable (the study did not involve humans).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable (the study did not involve humans).

Data Availability Statement

Data sources utilised were public documents. No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. 20 November 1989. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Engdahl, I. Implementing a national curriculum in Swedish preschools. Int. J. Early Child. Educ. 2004, 10, 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Barn och Personal i Förskola: Hosten 2022. Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/getFile?file=11339 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Curriculum for the Preschool, Lpfo 98/2010; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Läroplan för Grundskolan, Förskoleklassen och Fritidshemmet 2011: Rev. 2016; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.35e3960816b708a596c3965/1567674229968/pdf4206.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Margrain, V.; Lundqvist, J. Talent development in preschool curriculum and policies: Implicit recognition of young gifted children. In Challenging Democracy in Early Childhood: Engagement in Changing Global Contexts; Margrain, V., Löfdahl Hultman, A., Eds.; Springer: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019; pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Margrain, V.; Hope, K.; Stover, S. Pedagogical documentation and early childhood assessment through sociocultural lens. In Encyclopedia of Teacher Education: Living Edition; Peters, M.A., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Available online: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-981-13-1179-6_350-1 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Åsén, G.; Vallberg Roth, A.-C. Utvärdering i Förskolan—En Forskningsöversikt. Vetenskapsrådets Rapportserie, 6. 2012. Available online: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1410411/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- McLachlan, C.; McLaughlin, T. Revisiting the roles of teachers as assessors of children’s progress: Exploration of assessment practices, trends, and influences over time. In Assessment and Data Systems in Early Childhood Settings: Theory and Practice; McLachlan, C., McLaughlin, T., Cherrington, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-19-5959-2 (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Hitta Matematiken—Nationellt Kartlaäggningsmaterial i Matematiskt Tänkande i Förskoleklass; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/forskoleklassen/kartlaggning-i-forskoleklassen#h-Hittamatematiken (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Hitta Språket–Nationellt Kartläggningsmaterial i Spraåklig Medvetenhet i Förskoleklass; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/forskoleklassen/kartlaggning-i-forskoleklassen#h-Hittaspraket (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Ackesjö, H. Early assessments in the Swedish preschool class: Coexisting logics. Cepra-Striben Tidsskr. Eval. I Praksis 2021, 27, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walla, M. Diversity of assessment discourses in Swedish and Norwegian early mathematics education. J. Child. Educ. Soc. 2022, 3, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Läroplan för Grundskolan, Förskoleklassen och Fritidshemmet: Lgr22; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/getFile?file=9718 (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Daglioglu, H.E.; Suveren, S. The role of teacher and family opinions in identifying gifted kindergarten children and the consistence of these views with children’s actual performance. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2013, 13, 444–453. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, M. Exceptionally gifted children: Long-term outcomes of academic acceleration and nonacceleration. J. Educ. Gift. 2006, 29, 404–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skolverket. Särskilt Begåvade Elever [Gifted Students]; Skolverket. 2015. Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/inspiration-och-stod-i-arbetet/stod-i-arbetet/sarskilt-begavade-elever (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Ivarsson, L. Principals’ perceptions of gifted students and their education. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 7, 100400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. The differentiated nature of giftedness and talent: A model and its impact on the technical vocabulary of gifted and talented education. Roeper Rev. 1995, 18, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirri, K.; Kuusisto, E. Teachers’ Professional Ethics: Theoretical Frameworks and Empirical Research from Finland; Brill: Hong Kong, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Renzulli, J.S.; Reis, S.M. The three-ring conception of giftedness: A developmental approach for promoting creative productivity in young people. In APA Handbook of Giftedness and Talent; Pfeiffer, S.I., Shaunessy-Dedrick, E., Foley-Nicpon, M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margrain, V. Bright sparks: Att tända gnistor i svensk förskolor. In Särskild Begåvning i Praktik och Forskning; Sims, C., Ed.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2021; pp. 121–144. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, M.; Stack, N. Building knowledge bridges: Synthesising early years and gifted education research and practice to provide an optimal start for young gifted children. In The SAGE Handbook of Gifted and Talented Education; Wallace, B., Sisk, D.A., Senior, J., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Margrain, V. Narratives of young gifted children. Kairaranga 2010, 11, 33–38. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ925414.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hamzić, U.; Bećirović, S. Twice-exceptional, half-noticed: The recognition issues of gifted students with learning disabilities. MAP Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margrain, V.; van Bommel, J. Implicit and inclusive early education for gifted children: Swedish policy and international practice possibilities. In Special Education in the Early Years. Perspectives on Policy and Practice in the Nordic Countries; Harju-Luukainen, H., Bahdanovich Hanssen, N., Sundqvist, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, S. Curriculum work and hermeneutics. Curric. J. 2023, 00, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Lärarhandledning Aktivitet Mönster; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.3770ea921807432e6c729ea/1656577715731/Aktivitet%20M%C3%B6nster.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Lärarhandledning Aktivitet Tärning; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.3770ea921807432e6c729ec/1656577715808/Aktivitet%20T%C3%A4rningsspel.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Lärarhandledning Aktivitet Sanden/Riset; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.3770ea921807432e6c729eb/1656577715770/Aktivitet%20Sanden%20riset.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Lärarhandledning Aktivitet Lekparken; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.3770ea921807432e6c729e9/1656577715579/Aktivitet%20Lekparken.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Lärarhandledning Aktivitet 1: Vi Berättar & Beskriver; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.3770ea921807432e6c729c4/1656577280556/Aktivitet%201%20Vi%20ber%C3%A4ttar%20och%20beskriver.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Lärarhandledning Aktivitet 2: Vi Lyssnar & Samtalar; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.3770ea921807432e6c729c5/1656577280598/Aktivitet%202%20Vi%20lyssnar%20och%20samtalar.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Lärarhandledning Aktivitet 3: Vi Kommunicerar Med Symboler & Bokstäver; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.3770ea921807432e6c729cc/1656577403513/Aktivitet%203%20Vi%20kommunicerar%20med%20symboler%20och%20bokst%C3%A4ver%20Specialskolan.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Swedish National Agency for Education (SNAE). Lärarhandledning Aktivitet 4: Vi Urskiljer Ord & Språkljud; SNAE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.3770ea921807432e6c729c7/1656577280636/Aktivitet%204%20Vi%20urskiljer%20ord%20och%20spr%C3%A5kljud.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Skollagen. SFS 2010:800 [Education Act] (2010). Available online: http://www.skolverket.se/regelverk/skollagen-och-andralagar (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Swedish Research Council. Good Research Practice. 2017. Available online: https://www.vr.se/english/analysis/reports/our-reports/2017-08-31-good-research-practice.html (accessed on 20 May 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).