Abstract

The podcast in higher education is becoming widespread as a pedagogical tool that empowers students to take ownership of their own learning. In this article, we analyze a didactic experience carried out with undergraduate students at the Complutense University of Madrid and reflect on its potential for the development of curriculum content and student competencies. Using both quantitative and qualitative anthropological methodologies, we documented the process of podcast creation of undergraduate students by comparing their learning outcomes with those of students who received podcasts only as subject materials but did not engage in any creative process. Data from participant observation were supplemented with questionnaires administered to the same groups of students. The main findings indicate that the use of podcasts enhances the motivation and involvement of students in the learning process, helping them to relate in a meaningful way and to better understand theoretical content.

1. Introduction

Podcasting in educational contexts is becoming increasingly common [1]. The learning process benefits from the flexibility involved beyond the physical and temporal space of the classroom and the control students gain to conduct knowledge acquisition at their own pace. However, there has been little research in Spain on the potential of using podcasts when the group of students is responsible for the design and development of their content. In this sense, we were interested in analyzing our students’ willingness to use podcasts as a personal knowledge acquisition tool as a first approach to the subject, rather than measuring learning in terms of acquired knowledge or the extent of such an acquisition.

This paper systematizes and evaluates an experience of podcast development by students from different degrees of Social Sciences at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM, Spain). The format chosen was an audio podcast in .xml and .rss format that was used to distribute content on the web. To explore the potential of this tool for collaborative learning and student engagement, an interdisciplinary group of professors, students, and administrative staff of the Complutense University of Madrid designed and implemented an innovation teaching project during the academic year 2022–23.

The main objectives of the project were as follows:

- -

- To develop and improve the digital competencies of students, professors, and administrative staff of our university and innovate the use of open educational resources;

- -

- To collectively compare the challenges and opportunities involved in their use;

- -

- To evaluate the experience and transfer it to the rest of the educational community through participation in conferences and/or papers and with a seminar that will be edited in podcast format and made available online and in open access.

This experience had specific educational goals:

- -

- To achieve higher levels of motivation for learning;

- -

- To improve the understanding of contents, avoiding plagiarism in exams;

- -

- To enhance students’ engagement in the teaching–learning process;

- -

- To develop specific attitudinal competencies, such as autonomy in decision making to generate content and collective organization skills for a specific task.

The Use of Podcasts as an Innovation in Higher Education

Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) have become an integral part of educational curricula, encompassing the knowledge and skills that students are expected to acquire. The COVID-19 pandemic compelled schools and universities to transition to online teaching, leading to an extensive involvement of professors in developing asynchronous and synchronous lessons.

Podcasts have emerged as a versatile tool in the educational landscape, empowering students in their learning process by enabling them to set their own pace and share materials with their peers. The integration of technology has been recognized as a key innovative aspect in higher education, given its potential to transform traditional teaching strategies and enhance knowledge acquisition. Podcasting, coined by Ben Hammersley by combining “pod” (from the music player “iPod”) and “broadcasting”, [2] exemplifies a resource that has revolutionized virtual educational environments.

A podcast typically consists of audio files that delve into specific subjects, organized as individual chapters or within a series. Supplementary information such as a brief description, publication date, duration, and authorship accompany each podcast episode. Users can subscribe to an alert system to receive notifications about new podcast releases.

Educators utilize podcasts in various ways, including delivering class sessions, explaining content, assigning exercises and tasks, and providing feedback to students. Podcasts also serve to expand on classroom content and can be used to preview upcoming sessions by posing questions or highlighting topics for analysis. Systematic reviews on the use of podcasts in planning education highlight how podcasts may support active learning among students and create dialogues between students and communities under-represented in mainstream debate and the extent to which they may enhance strategies of blended and active learning in planning curricula [3]. Other studies suggest that university students and educators find podcasting to be a unique way to engage with content [1].

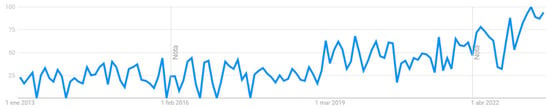

While international experiences with podcasting are growing, its use in the Spanish context remains relatively limited and intuitive [4]. However, there has been a notable increase in interest in podcasting in Spain since 2020, particularly due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interest in search time for the term “podcast” between 2013 and 2023 (Google Trends, 2023).

Podcasts serve as a valuable tool for facilitating knowledge acquisition among students with special educational needs, such as those with attention deficit disorder (ADD) or visual impairments, as well as those who are learning a new language. These students can access podcast materials repeatedly, at their own pace, which enhances their learning experience. The personalized and modulated nature of podcasts strengthens the connection between teachers and students; increases student interest and participation; and promotes experiential, autonomous, and meaningful learning [4,5].

Early academic papers exploring the use of podcasts in education highlighted their potential in the teaching–learning process [6]. They emphasized experiential activities that foster inclusiveness, improve students’ attention and satisfaction, and reduce the anxiety or frustration associated with studying [7,8,9,10]. Subsequent reviews in 2009, both general and focused on higher education, further examined the use of podcasts [11,12]. These initial works were followed by reviews specific to various disciplines [13,14,15,16,17].

In 2020, Celaya, Ramírez-Montoya, Naval, and Arbués conducted a comprehensive review that encompassed all of the literature related to podcasting for educational purposes in any discipline. Their systematic literature mapping method was employed to classify the published literature from 2014 to 2019, based on uses, contexts, and categories of audio podcasting for educational purposes. This analysis identified authors, reference journals, and trends in the field, using a sample of open-access articles indexed in the Web of Science and Scopus databases. This review explored the educational potential of podcasting and proposed new research directions for future studies, going beyond viewing podcasting as a mere substitute or supplement to lessons and exploring the more creative side of podcasting, “which would imply that students create content from what they have learned” [18].

The accessibility of software for creating and editing audio and video files; the widespread availability of mobile devices such as iPods, MP3 players, PDAs, and smartphones; and the integration of these tools in the identity of “digital natives’’ have created a positive inclination towards their use in educational contexts. This poses both a challenge and an unparalleled opportunity for teachers and educational innovation. Beyond knowledge transmission, podcasting enables teachers to contribute to the generation of social and personal dynamics, as expressed by Woodlang and Klass (2005): “Podcasting is not simply a new way to distribute audio recordings; it’s a form of expression, interaction, and community building” [19].

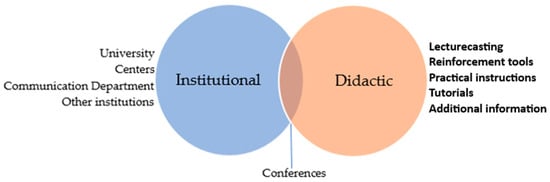

Various uses of podcasts in higher education include lecture casting, providing fieldwork instructions, explaining laboratory work or simulations, reinforcing specific content, delivering basic or preparatory material, offering personalized comments or information, presenting extension or current topics, and promoting teaching and institutional activities [20].

Podcasts serve as valuable educational resources (Figure 2), supporting various instructional purposes, such as lecture-casting, reinforcement, practical instructions, tutorials, and complementary information. They offer students an additional avenue for learning, enabling them to engage with content in a flexible, accessible, and personalized manner.

Figure 2.

Typology of podcasts from Spanish universities on iTunes U (adapted from Piñero-Otero, 2011) [4].

Lecture-casting, or the use of podcasts to capture and deliver lecture content, has become a popular approach in higher education. It allows students to access recorded lectures at their own convenience, providing flexibility and the opportunity for review.

Podcasts can also be used as reinforcement tools, providing additional resources and materials to support the learning process. These reinforcement podcasts can cover specific topics or concepts, offering in-depth explanations, examples, and exercises to enhance understanding.

Another practical use of podcasts is providing instructional guidance or practical instructions. Podcasts can serve as audio tutorials, guiding students through hands-on activities, experiments, or simulations. They can provide step-by-step instructions, tips, and insights to help students successfully complete tasks or projects.

Additionally, podcasts can offer complementary information to supplement classroom instruction. They can include interviews with experts, case studies, real-life examples, or current updates and developments in a particular field. These podcasts expand on the content covered in class and provide students with additional perspectives and insights.

The use of podcasts as a teaching methodology can be traced back to the early days of the technology. In 2004, evidence of its application emerged in Japan [21], while in 2005, Duke University in the United States started incorporating podcasts into their educational practices [22].

In Spain, the ARCA Project stands out as a notable initiative in the field of podcasting for education. ARCA, which stands for “RSS Aggregator for the Academic Community”, provides a centralized virtual space where members of RedIRIS, the Spanish academic and research network that provides advanced communication services to the national scientific and university community, can access multimedia content. This project aims to bring together various educational resources in a single platform. Additionally, in May 2011, several Spanish universities, including the University of Alicante, University of Valladolid, Polytechnic University of Madrid, King Juan Carlos University, University of Vigo, and IE Business School/IE University, established their channels on the iTunes U Spain platform. This platform, created in 2009, serves as a hub for educational content from these institutions.

These initiatives highlight the early adoption of podcasting in educational settings and demonstrate the integration of podcasting into the academic landscape, both internationally and in Spain.

2. Materials and Methods

Within the general objectives of the teaching innovation project implemented during the 2022–23 academic year in which this study is framed, the primary objective of the present research was to evaluate the potential use of podcasts in teaching and learning processes in higher education, with the aim of exploring alternatives to address significant academic literacy issues [23], specifically in regard to motivation, skills acquisition, content comprehension, and student engagement in the teaching–learning process. For this purpose, the study aimed to investigate the impact of podcasts by comparing the experiences of “passive” reception and “active” creation of sound pieces. Additionally, we sought to analyze potential synergies between the tasks of listening and creating sound pieces—whether the experience of creating sound pieces could affect the experience of receiving them. This study was proposed as a first exploratory approach to the use of podcasts as teaching–learning tools among university students of social sciences in the Spanish context, with the idea of guiding future extensions and continuations of the research in a greater diversity of knowledge areas and geographical contexts. The sample used in the present study is, therefore, quite limited but sufficient to detect the most significant dimensions, which also corresponded to what was found in the qualitative responses, as is shown in the results resulting from the triangulation of both sources of information (quantitative and qualitative).

This exploratory research was conducted with 78 students from the Complutense University of Madrid during the second semester of the academic year 2022–2023 (February–July 2023), according to the Spanish academic calendar. The students were enrolled in either the Introduction to Anthropology course in the Tourism Degree program or the Political Anthropology course in the Anthropology Degree program. The participants were divided into three groups: (1) listeners (who received podcasts recorded by professors and other students explaining theoretical content), (2) listeners and makers (who received podcasts and created their own podcasts to explain theoretical content), and (3) makers (who solely created their own podcasts without listening to the ones recorded by others).

Students who were tasked with designing and recording their own podcasts were instructed to form small groups consisting of 3–5 people and select a relevant topic to develop. For example, in the Political Anthropology course, the objective was to connect key concepts with a current political conflict, while in the Introduction to Anthropology course, students were asked to work on examples to develop classical concepts. Submitting the podcast script was a mandatory task for Political Anthropology students, whereas recording it was optional (although all groups ultimately recorded and submitted their sound pieces). For Tourism degree students, the podcast itself was an assessable submission. In both cases, this active teaching–learning process was carried out through partial drafts and weekly monitoring meetings.

Neither the podcasts created by the professors nor those recorded by students were professional. The creation process itself was intended as a learning process, aimed at acquiring skills in podcast recording and platform management, as well as expressing relevant anthropological concepts in a more accessible, everyday language. Examples, interviews, sound resources, and other tools were employed to bridge the gap between theory and mainstream reality.

While the professors had no previous experience in creating podcasts, some students had prior experiences both within and outside the university. Consequently, the nonprofessional audio quality of the pieces shared with the students may have negatively influenced their perception of them. Both groups 1 and 2 received the same podcasts to enable meaningful comparisons. Additionally, sharing podcasts created by the students themselves, rather than solely relying on those created by the professor, aimed to ensure a rich and diverse range of topics, formats, and languages in the podcasts listened to by the students.

At the end of the term, two tools were used to evaluate the impact of this experience:

The first survey aimed to assess the students’ experience of receiving podcasts as learning materials. It consisted of 13 closed questions and two open-ended questions. The questionnaire was designed to be concise to reach most students, and it was completed by 68 students from the Tourism degree program.

The second survey was designed to evaluate the students’ experience of creating podcasts. It included 12 closed questions and two open-ended questions. This questionnaire was completed by 37 students.

Both surveys included the following common elements in the evaluation (Table 1):

Table 1.

Dimensions included as quantitative variables in both surveys.

In the evaluation of the podcast creation process, the following quantitative dimensions were also included in the survey (Table 2):

Table 2.

Dimensions included as quantitative variables in the podcast creation related survey.

In both surveys, two open-ended questions were included, to which the students responded in writing and without space or time limitations: the first one dealt with the general evaluation of the experience (potentialities and limitations), and the second one dealt with the aspects to be improved. The responses of all the students were transcribed in a word processor and then subjected to a thematic analysis. The purpose of the qualitative approach was, on the one hand, to contrast the most relevant elements arising from the analysis of the quantitative information provided by the surveys and, on the other hand, to allow the emergence of new themes and dimensions not previously taken into account by the researchers.

The assumption is that, when viewing a phenomenon using different lenses or perspectives (including qualitative and quantitative methods, as well as diversity of information sources), it will be possible to arrive at more complex and integrated descriptions. So, unlike the qualitative research proposals, which are oriented exclusively to the understanding, and quantitative research proposals, which are oriented specifically to the quantification, this study seeks to articulate both perspectives [24].

In total, 78 students responded to the questionnaires: 26 both received and created podcasts, 42 only received podcasts created both by teachers and students, and 10 only created podcasts. Therefore, 68 students are considered to be listeners and 36 to be creators for the purposes of this study.

Characterization of the Sample in Relation to Familiarity with and Use of Podcasts

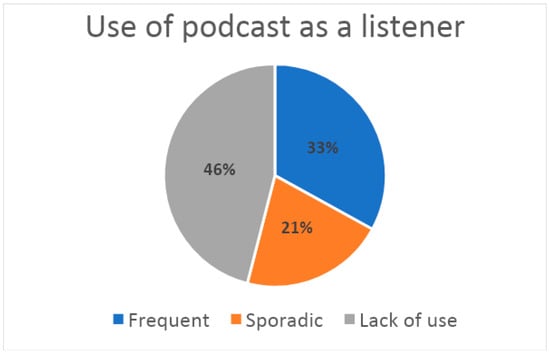

The students reported being quite familiar with podcasts as listeners (Figure 3), but they had limited experience as content creators (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Use of podcasts as a listener among the surveyed students (N = 78). Frequent use refers to students who listen to podcasts several times a month or more, while sporadic use refers to students who listen to podcasts once a month or less.

Figure 4.

Use of podcast as a creator (N = 78). Frequent use corresponds to students who create podcasts at least several times a month, while sporadic use corresponds to students who create them once a month or less.

A total of 54% of students had therefore listened to podcasts at least once, and more than half of them listened to them regularly. However, only 14% had ever had the experience of creating sound pieces.

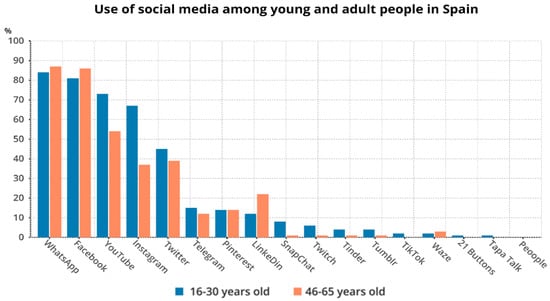

Approximately 90% of the students surveyed followed influencers and were regular users of social media. Only around 53% of students tended to be suspicious of the content they encountered on social media. The most used platforms among the students were TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, Spotify, and WhatsApp. These findings align with general data on social media usage by age in Spain, where younger populations tend to utilize platforms such as TikTok and Instagram more extensively, while networks such as Facebook are more popular among older people [25].

As shown in Figure 5, the use of social networks in Spain remains predominantly social, with activities centered on chatting and interacting with contacts (WhatsApp and Facebook). This is followed by activities involving the consumption of audio–visual content (YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook), although not exclusively audio focused. This observation aligns with our study findings, as approximately 54% of the surveyed students had ever listened to podcasts, while 87% watched viral videos on social media more frequently. Students’ comments further confirm this preference for visual content over strictly audio content: “I follow around 3 podcasts, but honestly, I never listen to them. I prefer the video format”. When examining the most frequently mentioned podcasts, this trend is reinforced by the fact that two out of the three most popular podcasts among students were in video format (Nude Project and Andrew Tate). The Wild Project is the only strictly audio podcast followed by the students in this study.

Figure 5.

Use of social media among young and adult people in Spain. Source: [25].

3. Results and Discussion

Since both qualitative and quantitative data were collected and both sources of information are complementary, the results and discussion are presented here together. First, the levels of satisfaction and the impact of the reception experience are analyzed and compared to the experience of creating sound pieces. Then, some potential synergies between the tasks of listening and creating sound pieces are outlined.

3.1. The Task of Listening

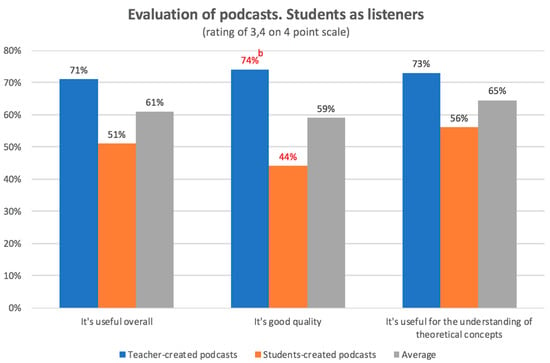

When analyzing the perceptions of using podcasts as learning materials, specifically the experience of receiving and listening to podcasts that explain theoretical concepts, it is evident from Figure 6 that most students rated the experience positively. On average, approximately two-thirds of the students found that the podcasts they listened to helped them understand the theoretical concepts, and more than half considered them to be of good quality and generally useful.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of podcasts by students as listeners to sound pieces created by the teacher and other students (N = 68). Statistically significant differences are marked with the red data and the letter b.

Comparing the ratings of podcasts created by other students to those created by the teacher, the former generally received lower ratings, with quality being the only statistically significant difference between the two. This suggests that a decrease in the quality of podcasts used for the students as listeners may affect their perceived usefulness as course materials. Nevertheless, as claimed by Moreno Mosquera [23] podcasts have significant potential in bridging the gap for students with lower levels of literacy, such as first-year students in the Tourism degree program at the Complutense University of Madrid.

Professors who participated in this research, including those who had previously taught these courses, confirmed the challenges students face in understanding academic texts and articles, as well as the writing difficulties encountered by students at this level.

The podcasts created by the professor were found to be useful for understanding theoretical concepts by nearly three out of four students. These findings support Gunderson and Cumming’s [1] argument on podcasting as a relevant tool for university students’ engagement with contents.

It is important to note that the professor had no prior experience in creating podcasts, thus further confirming the effectiveness of podcasts in the teaching–learning process, even without professional skills or technical means. Both the professor and most students who created sound pieces used free platforms such as Spotify, solely relying on their personal computers or phones. Some students even utilized the multimedia room of the faculty to achieve more professional results.

When analyzing the open-ended responses provided by the students in relation to their experience as listeners, three patterns of meaning or themes were found that contributed to the usefulness of podcasts as listeners: accessibility, proximity of content, and the playful aspect of the experience. Podcasts were perceived as accessible because they could be listened to multiple times, even outside the university context, and the spoken language was considered more comprehensible and enjoyable compared to written text. The following comments from students support this notion: “Understand subject topics orally, which helps more to understand than by reading”. “They provide knowledge in a short period of time and in an accessible way”. “More accessible information, the possibility of listening to them as many times as you need”.

The nontraditional format of podcasts, diverging from conventional academic lectures and texts, allowed content creators to expand information, use contextualized examples, and present them in an engaging and accessible manner. The inclusion of various sound resources, interviews, and other tools reflected the dialogic and communicative context that students are familiar with in their daily lives. Students made the following statements: “Podcasts provide an example and another basis for being able to understand the subject”. “They give information but in an enjoyable and easy-to-understand way”. “They show different perspectives of the subject”. “It is a more interactive way of learning”. “The information they provide is richer”.

The use of podcasts was seen as an opportunity to bring the discipline closer to students and make it more relevant and meaningful. The diversity of voices, tones, and discourses that can be included in podcasts, as well as the oral nature of the discourse itself, enhanced students’ engagement with the anthropological discipline and the method of ethnography, enriching their disciplinary literacy [22] within the university context, particularly in the field of social sciences. However, students acknowledged that the potential of podcasts relies on their quality: “Depending on the podcast and how it is composed, it can be beneficial for the subjects and the students, especially in explaining the content in a more dynamic way, with the possibility of listening to it more than once”.

Lastly, students perceived listening to anthropological podcasts as an original, different, and playful experience that increased their motivation. It provided a deeper understanding of topics covered in class, expanded their information, and sparked their attention and interest. The experience of listening to podcasts in university subjects “increases students’ motivation and disseminates more knowledge about the subject”. “It is a more entertaining way of learning”. Podcasts generated more interest in students, facilitating a better understanding of concepts that may have been unclear in class. It was described as a dynamic form of lecture. The importance of the playful aspect in teaching–learning processes has been relatively understudied in higher education, with more focus on the benefits of gamification [26,27,28,29] that tend, implicitly or explicitly, to differentiate between gamification and game or gamification and play experience in general—not necessarily linked to specific contents to be learned or specific skills to be acquired. However, as studies by Forbes [30] have recently shown, this paper also suggests that adopting a broadly understood playful approach, such as through podcast listening and podcast creating, can improve student motivation and remove barriers to learning, fostering an engaged and open attitude that facilitates the learning process.

3.2. The Task of Creating

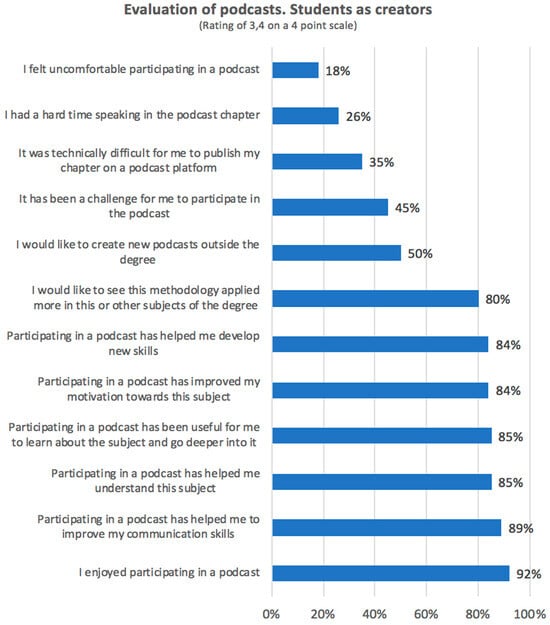

When examining students’ perception of using podcasts as activities where they themselves become creators of audio content as part of continuous assessment in their subjects, the feedback is highly positive (Figure 7). Most students, 84%, believed that participating in the creation of a podcast related to the subject content enhanced their motivation towards the subject. Additionally, approximately 87% perceived the experience as useful for acquiring or improving competencies and skills, particularly in communication. Furthermore, 85% felt that the activity helped them better understand and delve deeper into the subject concepts, while 92% valued the enjoyable aspect of the experience.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of podcasts by students as creators of sound pieces (N = 37).

However, it is worth noting that around one in five students encountered difficulties in speaking on the podcast or felt uncomfortable doing so. Unlike other innovative teaching tools that allow for anonymous participation, such as Mentimeter or Kahoot [31], podcast creation requires students to use their voices and often interpret the script prepared by the audio-piece creators. While this may pose challenges for more introverted students, it is important to recognize that oral presentations are commonly expected in university classes, where students are required to present their work live in front of the entire class. On the positive side, the absence of anonymity in podcast creation allows teachers to assess the activity, and it provides an opportunity for more reserved students or those with diverse oral communication abilities to rely on their classmates. This contributes to the podcasting benefits for inclusiveness stated by both Boulos et. al and Chan et.al [7,8,9,10]: workload can be distributed in a manner that accommodates the diversity present in the university classroom, particularly in group podcast projects as the ones assessed in this study.

These quantitative results are consistent with the common themes found in the students’ spontaneous responses, with the playful and innovative dimension of the collaborative process of content creation being the trigger, in the students’ experience, of increased motivation and of meaningful experimentation with new skills and theoretical contents.

As the quantitative data show, the collaborative aspect of teamwork was, in fact, highly valued by students in the podcast creation experience: “What I liked most about this experience are the anecdotes that have remained after doing the podcast all together”. “The best thing has been working with my colleagues and sharing the experience”. The playful, innovative, and fun nature of the collaborative creation process was also highlighted: “What I most enjoyed was having a good laugh with my colleagues while doing it”; “…being able to express our knowledge in a different way to what we are used to”. The teamwork and innovative nature of the activity made it enjoyable and meaningful for many students, connecting it with the theoretical content and topics covered: “Editing the podcast was something I really enjoyed and my colleagues really liked it too”. As one student described it, the innovation of the process and the collaborative and creative nature of it allow students to turn the theoretical curricular contents of the subjects into meaningful contents, that is, into knowledge felt as their own: “I really liked this experience since it allows us to explore other ways of assessment and also allowed a better understanding of the theoretical subjects. I think it is a very innovative and educational initiative, since it allows us to better expose our knowledge”.

The incorporation of a playful dimension into the learning process did not diminish its pedagogical value; instead, it increased motivation and brought meaning to the content and subjects studied, as has also been proven in other studies in recent years [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Having fun during the process enhanced motivation and helped students develop a sense of ownership over the knowledge they acquired: “The best thing has been researching about the subject…talking with my classmates about interesting topics”; “learning more about concepts of the subject”; and “being together with my classmates with some freedom to record and talk about the proposed topic”. It allowed for an exploration of alternative assessment methods and provided a better understanding of the theoretical subjects.

As the quantitative data show (Figure 7), almost half of the students experienced the podcast creation as a challenge. One in four faced challenges related to participation, while one in three struggled with technical aspects of creating and publishing the audio pieces. However, even those who encountered difficulties found value in the experience, as shown by the fact that 92% of the students stated that they enjoyed the podcast creation exercise, and as corroborated by the qualitative information, as well. They enjoyed the process because it helped them understand the subject better and made it more entertaining and less burdensome. The challenge was seen as a positive aspect, as it enriched the teaching–learning process by transforming reflection and debate on theoretical concepts into a playful experience.

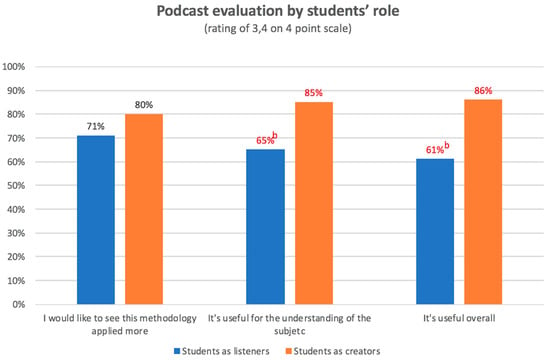

When comparing the evaluation of the experience of listening to podcasts with the experience of creating podcasts, it becomes evident how important it is to involve students as active and creative participants in their own learning processes (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Podcast evaluation by students’ role (N = 78). Statistically significant differences are marked with the red data and the letter b. The general usefulness category includes dimensions related to understanding theoretical concepts, acquiring skills, and increasing motivation.

In line with Piñeiro-Otero and the team of Cabero and Gisbert [4,5], both quantitative and qualitative findings suggest that students’ use of podcasts, whether as listeners or creators, positively impacts the understanding of theoretical concepts, acquisition of competencies, and motivation. However, the effect is significantly stronger when students actively participate in creating the audio content alongside their peers, rather than just consuming it. While around two-thirds of students found the experience of listening to podcasts useful, this proportion increased to nearly nine out of ten for the experience of creating sound pieces (Figure 8).

Moreover, most students expressed a desire to see the continued use of podcasts as pedagogical tools in university classrooms. Although the preference was slightly higher among student creators (80%) compared to student listeners (71%), this difference is not statistically significant (Figure 8). This suggests that both groups recognize the value of podcasts in enhancing their learning experiences and are interested in further incorporating them into their educational journey. Clearly, our results, in this sense, match Moreno Mosquera’s [23] claim on the benefits of podcast use for student engagement in the teaching–learning process and skill acquisition.

3.3. Possible Synergies

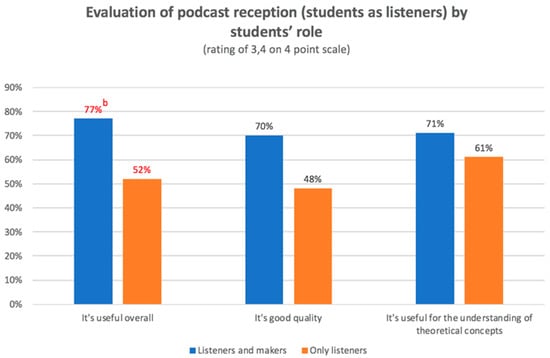

Possible synergies between the tasks of listening and creating sound pieces were also analyzed in an exploratory manner, that is, whether the performance of one of these tasks could be affecting the pedagogical potential and overall experience of the other. Due to the low number of students evaluated who only created podcasts but did not receive sound pieces as listeners, it was not possible to delve into the possible effect that receiving podcasts as listeners could have on the students’ creative experience of podcasts. However, it was possible to analyze the effect of the experience of creating sound pieces on the experience of receiving them by comparing the groups of students who received and created podcasts and those who only listened to the sound pieces created by the professors or by other students. Both groups of students were in the first year of the Tourism degree at the Complutense University of Madrid, so their academic trajectories, as well as their sociodemographic and personal characteristics, can be considered similar.

As can be seen in Figure 9, the evaluation of the reception of podcasts as subject materials by students is more positive among those students, who, in addition to listening to sound pieces, also participated in the creation of podcasts. The perception of the general usefulness of the podcasts listened to and their specific usefulness for the understanding of the theoretical contents of the subjects, as well as the perception in relation to the quality of the sound pieces listened to, is higher among students who both listen to and create podcasts. However, this tendency is only statistically significant for the perception of the general usefulness of the sound pieces listened to.

Figure 9.

Evaluation of podcast reception (students as listeners) by students’ role (N = 68). Statistically significant differences are marked with the red data and the letter b. Percentages include ratings received for both teacher-created podcasts and podcasts created by other students.

As was also confirmed qualitatively, students who participated in the creative process of collaboratively designing and recording their own podcasts had a more open attitude and greater motivation and interest in listening to podcasts created by others. Highlighting Celaya et. al.’s [18] arguments on the creative side of podcasting, our findings suggest that tasks entailing the more active and creative involvement of students in the generation of certain materials, such as the creation of sound pieces, in addition to facilitating the learning processes, tend also to improve the receptivity and pedagogical potential of those same materials even when the student’s role is that of a more “passive” receiver of them. This could be of great interest for curricular and pedagogical design in higher education, since the role of students is varied and the time and resources available; moreover, the requirements of the different disciplines and subjects do not always allow students to be involved as creators in the materials they receive.

4. Limitations and Opportunities

This study highlights some limitations and areas for improvement regarding the use of podcasts in higher education. When it comes to students listening to podcasts, the quality of the podcasts created by teachers and students themselves plays a crucial role in their pedagogical effectiveness. Lower-quality podcasts may hinder the learning experience. Additionally, students have expressed a preference for podcasts that incorporate visual elements alongside the audio. Considering mixed modalities could enhance students’ motivation and engagement with podcast-based materials.

In terms of students creating podcasts, the main limitation identified is the need for better technical infrastructure and equipment. Students have identified limitations related to technical infrastructure. They demand better equipment and more training for teachers to guide the recording process, aiming for higher quality and the ability to experiment with sound. Some students have even expressed a desire to continue recording episodes autonomously, exploring less formal academic formats. There is also interest in the possibility of creating programs featuring podcasts produced by students of political anthropology from different parts of the world.

To further improve the podcast creation experience, future experiences could focus on evaluating the participation of different group members in the podcast creation process. It would also be valuable to compare group experiences with individual podcast creation, considering strategies that promote inclusion and effective participation of all students in the classroom, regardless of their specific characteristics or needs.

Finally, and although it was not the main objective of the study, one of the limitations found stems from the difficulty of designing a common assessment tool to compare the effectiveness, in terms of learning, of incorporating podcasts for educational purposes in university classes. This is undoubtedly one of the future directions we intend to address. In this regard, we have several parallel and independent lines of research. The first one focuses on the effectiveness of using podcast technology in knowledge acquisition among university students; the second one examines the sustainability and maintenance of podcast use by university students; and the third one is oriented towards analyzing the potential of podcasts for disseminating, communicating, and promoting academic research.

By addressing these limitations and exploring opportunities for improvement, the use of podcasts in education can be enhanced, providing students with high-quality and engaging learning experiences.

5. Conclusions

The conclusions drawn from the study highlight the positive impact of podcasts in higher education. Podcasts are effective at bringing theoretical concepts closer to students, particularly benefiting those with low levels of literacy. The accessibility, proximity, and playful nature of listening to and creating podcasts enhance motivation and facilitate the development of competencies, skills, and knowledge among university students. The collective experience of podcast creation by students proved to have a greater impact on increasing motivation, enjoyment, and interest in the subjects and was perceived as a useful tool to a greater extent than the experience of receiving podcasts as listeners.

The collaborative experience of designing and creating podcasts contributes to the playful aspect of the teaching–learning process, transforming subject content into meaningful knowledge for students. This aligns with the principles of constructivist didactics [32], considering podcasts as innovative tools that support meaningful learning and assessment processes in the 21st century. By engaging in podcast creation, students actively construct their own content from disciplinary knowledge, allowing them to explore and make sense of complex social realities. This approach blurs the boundaries between traditional academic knowledge and popular multimodal content, challenging the traditional roles of students as passive recipients and teachers as active performers in knowledge generation.

Furthermore, fostering a sense of community and collective work among students is seen as highly productive. By working together towards a common project, such as a podcast channel, students not only learn explicit curricular content but also develop versatile skills relevant to their future professional lives. This approach encourages students to become active agents in their own learning and emphasizes the importance of collaboration and collective knowledge production. We encourage the formation of active subjects who formulate their own contents from disciplinary knowledge to construct meanings on problematic aspects of social reality [33], at the same time as we encourage the production of collective products of anthropological dissemination. This study advocates for the integration of podcasts as pedagogical tools in higher education, as well as involving students in the creation of learning materials in a variety of formats, highlighting their potential to transform teaching and learning practices, promote meaningful engagement, and prepare students for their future endeavors.

Overall, the use of podcasts in higher education holds significant relevance from both social and political perspectives. In theoretical terms, podcasts provide a means to democratize access to knowledge by delivering educational content in an accessible and easily shareable format. This can contribute to reducing educational disparities and ensuring that quality education is within reach of a wider audience. From a political standpoint, the integration of podcasts in higher institutions can bolster civic engagement and political awareness by enabling the dissemination of discussions and debates on social and political issues. Moreover, podcasts can serve as a powerful tool for fostering critical thinking and reflection on political and social matters, which is crucial in a democratic society. In this regard, higher education institutions have a responsibility to fully explore and harness the potential of podcasts as a tool to promote equity in education and enhance citizen participation in political and social discourse.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.G.E., M.S.C. and O.I.M.-C.; methodology, I.G.E.; resources, I.G.E. and M.S.C.; data curation, I.G.E., M.S.C. and O.I.M.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.G.E., M.S.C. and O.I.M.-C.; writing—review and editing, I.G.E., M.S.C. and O.I.M.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad Complutense of Madrid (Spain) under its “Innova Docencia” call for Educational Innovation Projects, grant number 2022/420. PI: Prof. Dr. José Ignacio Pichardo Galán. María Soledad Cutuli received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 847635.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of GINADYC—Universidad Complutense de Madrid (GINADYCUCM012021; 22 February 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available (in Spanish) upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gunderson, J.L.; Cumming, T.M. Podcasting in higher education as a component of Universal Design for Learning: A systematic review of the literature. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2022, 60, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, B. Audible Revolution, The Guardian. 2004. Available online: http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2004/feb/12/broadcasting.digitalmedia (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Moore, T. Pedagogy, Podcasts, and Politics: What Role Does Podcasting Have in Planning Education? J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-Otero, T. La utilización de los Podcast en la universidad española: Entre la institución y la enseñanza. Hologramática 2011, 15, 27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cabero, J.; Gisbert, M. La Formación en Internet: Guía Para el Diseño de Materiales Didácticos; Editorial MAD: Sevilla, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Earp, S.; Belanger, Y.; O’Brien, L. Duke Digital Initiative End of Year Report. Duke University, 2006. Available online: https://learninginnovation.duke.edu/pdf/reports/ddiEval0506_final.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Boulos, M.N.K.; Maramba, I.; Wheeler, S. Wikis, blogs and podcasts: A new generation of Web-based tools for virtual collaborative clinical practice and education. BMC Med. Educ. 2006, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, D.E.; Fisher, M. Neo Millennial User Experience Design Strategies: Utilizing Social Networking Media to Support ‘‘Always On’’ Learning Styles. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2006, 34, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Piller, M. Principal Factors of An Audio Reading Delivery Mechanism—Evaluating Educational Use of The Ipod. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Educational Multimedia., Hypermedia., and Telecommunications., Montreal, QC, Canada, 27 June–2 July 2005; Kommers, P., Richards, G., Eds.; AACE: Chesapeake, VA, USA; pp. 260–267. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.; Lee, M. An Mp3 a Day Keeps the Worries Away—Exploring the Use Of Podcasting To Address Preconceptions and Alleviate Pre-Class Anxiety Amongst Undergraduate Information Technology Students. 2005. Available online: http://www.csu.edu.au/division/studserv/sec/papers/chan.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Hew, K.F. Use of audio podcast in K-12 and higher education: A review of research topics and methodologies. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2008, 57, 333–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarr, O. A review of podcasting in higher education: A review of the literature with particular reference to iIts influence on the traditional lecture. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2009, 25, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas, R.G.; Gutiérrez, F.H.; Fragoso, M.V.; Arcos, C.M. Estudios sobre el podcast radiofónico: Revisión sistemática bibliográfica en WOS y Scopus que denota una escasa producción científica. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2018, 73, 1398–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, Q.S.; Thoma, B.; Milne, W.K.; Lin, M.; Chan, T.M.; Paterson, Q.S. A Systematic Review and Qualitative Analysis to Determine Quality Indicators forHealth Professions Education Blogs and Podcasts. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2015, 7, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M.; Hoon, T.B. Podcast Applications in Language Learning: A Review of Recent Studies. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2013, 6, p128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomicka, L.; Lord, G. Podcasting—Past, Present and Future: Applications of Academic Podcasting in and out of the Language Classroom. In Academic Podcasting and Mobile Assisted Language Learning: Applications and Outcomes; Facer, B.F., Abdous, M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, A.D.; Lambe, C.S.; Perryer, D.G.; Hill, K.B. Podcasts—An adjunct to the teaching of dentistry. Br. Dent. J. 2009, 206, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celaya, I.; Ramírez-Montoya, M.S.; Naval, C.; Arbués, E. Usos del podcast para fines educativos. Mapeo sistemático de la literatura en WoS y Scopus (2014–2019). Rev. Lat. 2020, 77, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, M.; Klass, D. Podcast Solutions, the Complete Guide to Podcasting; Apress, Inc.: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2005; p. 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, F. Profcast: Aprender y Enseñar con Podcast; UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Solano Fernández, I.M.; Sanchez Vera, M.M. Aprendiendo en Cualquier Lugar: El Podcast Educativo, Pixel-Bit. Rev. De Medios Y Educ. 2010, 36, 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Lankshear, C.; Knobel, M. New literacies: Everyday Practices & Classroom Learning; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera, E.M. Lectura académica en la formación universitaria: Tendencias en investigación. Lenguaje 2019, 47, 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, H.; Heale, R. Triangulation in research, with examples. Évid. Based Nurs. 2019, 22, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Social Media Family. Available online: www.epdata.es (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Borrás-Gené, O.; Martínez-Núñez, M.; Martín-Fernández, L. Enhancing fun through Gamification to improve engagement in MOOC. Informatics 2019, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Prados, M.A.; Collados Torres, L. La Gamificación Como Metodología de Innovación Educativa. V Congreso Internacional Virtual Sobre La Educación en el Siglo XXI Proceedings March 2020. Available online: https://www.eumed.net/actas/20/educacion/13-la-gamificacion-como-metodolog (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Oliva, H.A. La gamificación como estrategia metodológica en el contexto educativo universitario. Real. Y Reflexión 2016, 44, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, V.J.; Blázquez-Rodríguez, M.; Galán JI, P.; Carabantes-Alarcón, D.; Mancha-Cáceres, O.I.; Borras-Gené, O.; Ramos-Toro, M. Usando Mentimeter en educación superior: Herramienta digital en línea para incentivar y potenciar la adquisición de conocimiento de manera lúdica. Etic@ net. Rev. Cient. Elect. Edu. Com. Soc. Con. 2022, 22, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, L. The Process of Playful Learning in Higher Education: A Phenomenological Study. J. Teach. Learn. 2021, 15, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichardo, J.I.; López-Medina, E.F.; Mancha-Cáceres, O.; González-Enríquez, I.; Hernández-Melián, A.; Blázquez-Rodríguez, M.; Jiménez, V.; Logares, M.; Carabantes-Alarcon, D.; Ramos-Toro, M.; et al. Students and Teachers Using Mentimeter: Technological Innovation to Face the Challenges of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Post-Pandemic in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J.S.; Duhl, L. Book and film reviews: Toward a Theory of Instruction. Phys. Teach. 1966, 4, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier, S. Pedagogía de la Potencia y Didáctica no Parametral. Entrevista con Estela Quintar. Rev. Interam. De Educ. de Adultos 2009, 31, 119–133. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=457545096006 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).