Framing School Governance and Teacher Professional Development Using Global Standardized School Assessments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background of the Study

2.1. PISA-S as Part of the Expansion of OECDs’ Soft Regulatory Agency

2.2. PISA-S Features (2010–2022)

2.2.1. Objectives and Particulars

2.2.2. Assessment Characteristics

2.2.3. Implementation Diversity

2.2.4. PISA-M: The Portuguese Version of PISA-S

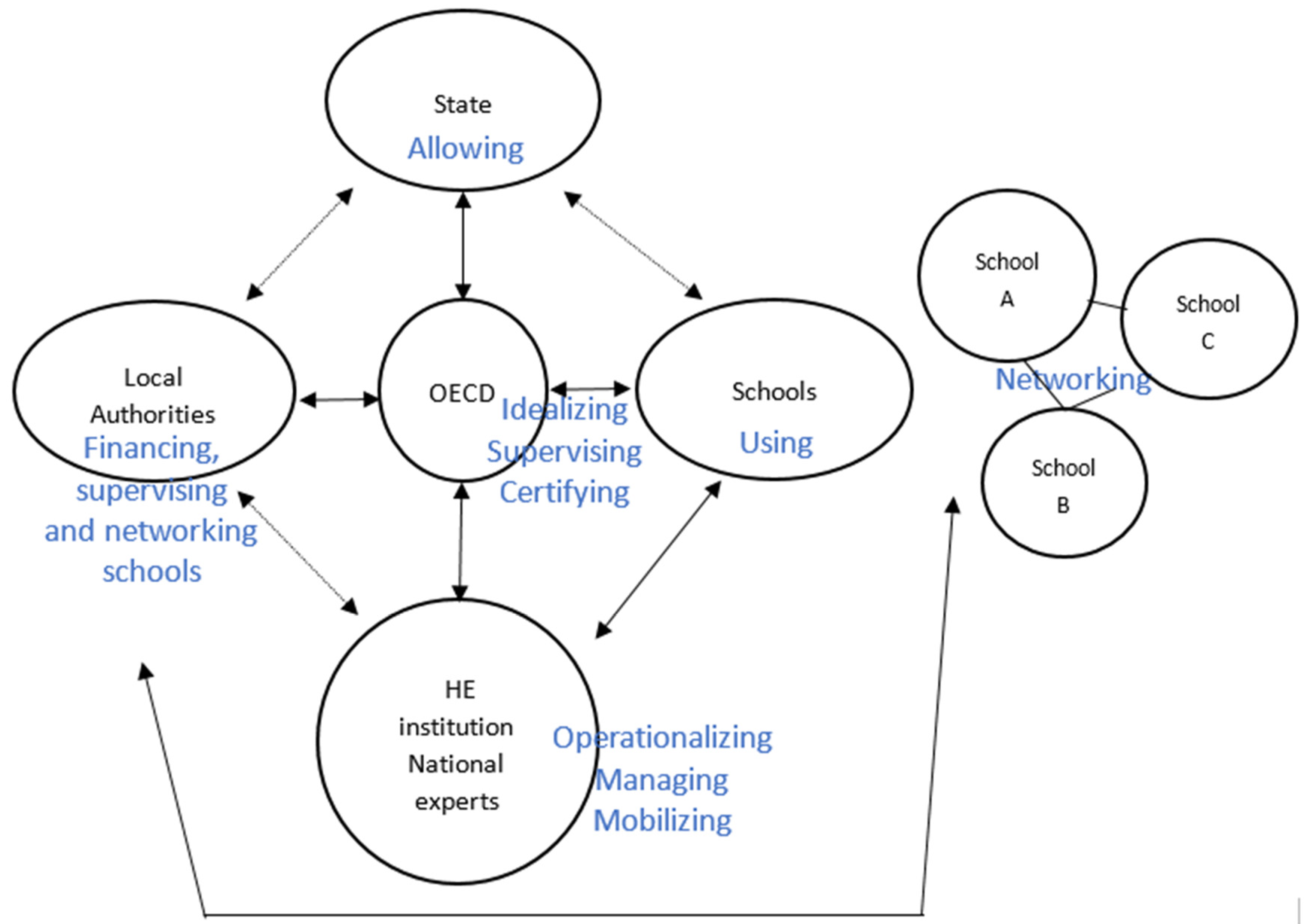

2.2.5. PISA-M and the Complexification of Local Governance

3. Theoretical Approach

3.1. Taking PISA-M as a Policy Tool

[…] the instrument is never an isolated device: it is inextricably linked to contextualized modes of appropriation. Via the instrument it is possible to observe not only professional mobilizations (for example, the affirmation of new competencies) but also reformulations (serving specific interests and power relations between actors) and, finally, resistance (to reduce the impact of the instrument or circumvent it by creating paradoxical alliances).(p. 15)

3.2. Frame Analysis as a Means of Capturing the Normative and Cognitive Purposes of PISA-M

4. Materials and Methods

5. Current Study

5.1. Adherence to PISA Tests to Address the Deficit of Objective Knowledge by Schools and Teachers

Schools began to convey the idea that participation in PISA was very interesting, but it did not have any direct return for schools, something that they expressed as extremely necessary to be able to act based on the results(National Coordinator, Parliamentary hearing) (Probl1)

The part of proposing actions and implementing these actions is exclusive to those who have this responsibility, and those who have this responsibility are those who experience the school in their day-to-day life and, specifically, school principals and teachers(National Coordinator, Forum with Trade Unions) (Solut1)

[PISA] collects a lot of information about the characteristics of students, which has proved to be extremely useful at the country level, and we believe it [PISA-M] can also prove to be very useful at the school level. (…)(National Coordinator, Parliamentary hearing) (Solut1)

[PISA-M aims to] provide schools with a set of information that allows for an internal and external analysis process, with the aim of favoring possible improvement solutions—strategies, tools, etc.(National Coordinator, Parliamentary hearing) (Solut1)

PISA is a common language from the point of view of the results, and it seems to us that it will be able to enhance this reflection and this sharing because it is clear and objective information(National Coordinator, Parliamentary hearing) (Solut1)

5.2. Adherence to PISA-M to Address the Lack of Collaboration and Reflection by Schools and Teachers

The schools, alone, based on that information, have a real picture of where they are and a clear notion of where they would like to go, but they are very limited in their capacity for action. (…) you shouldn’t leave schools alone to face their problems and look for… and hope that they find their solutions(National Coordinator, Forum with Trade Unions) (Probl2)

We are convinced that—if we manage to get schools to use this instrument in a network for subsequent sharing of results and for reflection and subsequent collaborative learning—we can have a greater impact on student learning. And it is in this sense that the PISA project was designed for schools in the municipalities of Portugal(National Coordinator, Parliamentary hearing) (Solut2)

It is necessary that those who make up the educational system share, reflect together, learn collaboratively and then manage to implement their solutions, which do not need to be solutions from others, but solutions that can be inspired by solutions from others, depending on the circumstances(National Coordinator, Parliamentary hearing) (Solut2)

And what is intended is to mobilize what the OECD can do well, which is an international mobilization of specialists in the field of education, but also the National Academy and this whole network of actors that work around education that must be able to contribute to this learning. Hence the name is collaboratory in this higher sense(National Coordinator, Parliamentary hearing) (Solut2)

Since the main objective of PISA is to enable schools to achieve permanent improvement in student learning outcomes, it is known that sharing, joint reflection, and networking, as well as collaborative learning, are essential approaches in the development of this training of schools(PISA-M website, IPL) (Solut2)

It is a project that aims to train schools; that information effectively helps them to improve the teaching-learning processes, but (…) we all know that the school alone is not able to do this.(National Coordinator, Parliamentary hearing) (Solut2)

(…) leads to the improvement of what schools seek to do every day, which is to teach better and that their students learn better.(National Coordinator, Forum with Trade Unions) (Solut2)

Therefore, the solution to problem 2 is that adherence to PISA-M allows schools to be part of a network that facilitates collaborative learning, thus impacting students learning. It mixes two main ideas: on the one hand, “research laboratory”, i.e., a label that is associated with the mobilization of objective data “measured in a very transparent way”; on the other hand, collaboration, as “effective learning” is imagined as coming out from an educational environment characterized by collaboration and sharing (National Coordinator, Forum with Trade Unions). In other words, the results do not stand for themselves. They need to be examined by teachers and experts to become usable, and the space for such convergence is the concept-practice of the “research collaboratory”.(Solut2)

(…) the application to each School of the OECD Test based on PISA will provide the participating schools with clear, objective, relevant and comparable information, nationally and internationally, which will allow reflection and internal and external sharing, as well as collaborative learning in a network structure of nets made up of Schools, Municipalities, Technicians, and Researchers in Education, together with political decision-makers and those in educational management, with regional or national intervention(PISA-M website, IPL) (Solut2)

5.3. Assigning the Leadership of the Network to Municipalities to Fill the Deficit of Coordination by Schools

Each of the actors in this network has its own picture, has its own diagnosis, whether it be an individual picture of each school, which concerns only each school, or a picture of the network … and can be related to a region, a municipality (…)(National Coordinator, Forum with Trade Unions) (Probl3)

“facilitators, both from a financial point of view and from the point of view of articulating the whole process”.(National Coordinator, Parliamentary Hearing)

[Municipalities are] increasingly assuming a very active role in boosting educational networks. They stopped looking at territorial development (…) exclusively with the variables they looked at until 15 years ago, they started looking at education as something strategic from the point of view of the development of their territories, and they have sought to play a collaborative and active role in this regard, and I have witnessed this over the last few years, in particular at the National Agency for Qualification and Professional Education, where I found extremely important partners in the municipalities… participatory and collaborative in building solutions(National Coordinator, Forum with Trade Unions) (Solut3)

Municipalities have been the basis of what we are doing in Portugal, in an innovative way, within the scope of the OECD precisely to maximize the potential of the instrument(National Coordinator, Forum with Trade Unions) (Solut3)

It is important that the results of applying a test such as PISA, the reports produced, and the surveys carried out to students are accompanied by group analysis, sharing of joint approaches, and collaborative learning coordinated by those who assume in their mission the search for the improvement of learning outcomes of students from all schools in each network. For these reasons, countries are starting to design the application of PISA for Schools in a logic of local territorial network with the coordination of the actors responsible for the territories(PISA-M website, IPL) (Solut3)

Municipalities are also empowered with municipal information on the characteristics and skills generation system for the future active population of their territory. Through this national and international benchmark, it is intended to enable the Municipalities, together with their Schools, to active participation in the development of the skills of the population they represent(PISA-M website, IPL) (Solut3)

5.4. Frame Alignment: Prioritizing Students’ Wellbeing, Collaboration, and School Autonomy

We cannot adopt strategies focused solely and exclusively on performance, which is relatively easy to do, except that it is often done at the expense of the well-being and overall happiness of the students who are involved(National Coordinator, Forum with Trade Unions) (FrAlign1)

If we raise cognitive indices, lowering the level of student satisfaction, we do not do a good job. The objective is for this project to be able to contribute to these two dimensions and, therefore, it is called improving the learning outcomes and well-being of students(National Coordinator, Parliamentary hearing) (FrAlign1)

The countries that have had the best results in recent years have been many eastern countries (…), but when we cross this performance with the happiness index (…) the trend is reversed. Those who are performing better are experiencing lower happiness scores. However, when we look at countries like, for example, the Nordic countries that no longer have the best performance indexes, their students continue to have very high levels of happiness and well-being. And it is at this intersection, this balance between cognitive performance and well-being and happiness that we should find the solutions(National Coordinator, Forum with Trade Unions) (FrAlign1)

We must be very careful in how the results will be mobilized, and how they will be shared outside the networks, and we will do everything to not influence the construction of rankings, in the wrong way as it has happened in terms of results between countries and at the national level. This critical factor has been identified and can weaken the whole process, as we all understand it(National Coordinator, Parliamentary hearing) (FrAlign2)

Based on information that is clear, that is objective, that is relevant, but that is also comparable to be able to promote dialogues because when it is not comparable, it is not possible to establish a collaborative dialogue(National Coordinator, Forum with Trade Unions) (FrAlign2)

A school that can position itself in relation to its country, will be able to position itself in relation to its municipality, it can position itself internationally if it is interested in that—and all this facilitates communication between these various actors(National Coordinator, Parliamentary hearing) (FrAlign2)

Sharing shouldn’t be for comparison, for positioning. It is supposed to identify problems and solutions(National Coordinator, Forum with Trade Unions) (FrAlign2)

The product for municipalities is their regional photography, the product for schools is their school photography. And the municipalities do not have the photo of the schools. This was defined from the beginning and there is an element of trust that must exist and that cannot be violated at any time, so what is school photography is for schools, and schools will do what they feel they should do with their photography(National Coordinator, Forum with Trade Unions) (FrAlign3)

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rinne, R.; Kallo, J.; Hokka, S. Too Eager to Comply? OECD Education Policies and the Finnish Response. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2004, 3, 454–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellar, S.; Lingard, B. The OECD and global governance in education. J. Educ. Policy 2013, 28, 710–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ydsen, C. The OECD’s Historical Rise in Education: The Formation of a Global Governing Complex; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, L.M. Revisiting the Fabrications of PISA. In Handbook of Education Policy Studies; Fan, G., Popkewitz, T.S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 259–273. [Google Scholar]

- Addey, C.S.; Sellar, S.; Steiner-Khamsi, G.; Lingard, B.; Verger, A. Forum Discussion: The Rise of International Large-scale Assessments and Rationales for Participation. Compare 2017, 47, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischman, G.E.; Marcetti Topper, A.; Silova, I.; Goebel, J.; Holloway, J.L. Examining the influence of international large-scale assessments on national education policies. J. Educ. Policy 2019, 34, 470–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorur, R. Seeing like PISA: A cautionary tale about the performativity of international assessments. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 15, 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, S.; Petersson, D.; Popkewitz, T.S. International Comparisons of School Results: A Systematic Review of Research on Large-Scale Assessments in Education. 2015. Available online: https://publikationer.vr.se/produkt/international-comparisons-of-school-results-a-systematic-review-of-research-on-large-scale-assessments-in-education/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Lindblad, S.; Pettersson, D.; Popkewitz, T. (Eds.) Education by the Numbers and the Making of Society: The Expertise of International Assessments; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lingard, B.; Martino, W.; Rezai-Rashti, G.; Sellar, S. Globalising Educational Accountabilities; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, S.; Lingard, B. The multiple effects of international large-scale assessment on education policy and research. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2015, 36, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockheed, M.E.; Wagemaker, H. International large-scale assessments: Thermometers, whips, or useful policy tools? Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2013, 8, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grek, S. Governing by numbers: The PISA ‘effect’ in Europe. J. Educ. Policy 2009, 24, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozga, J. Assessing PISA. Eur. Educ. Res.J. 2012, 11, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, D.; Thompson, G.; Rutkowski, L. Understanding the Policy Influence of International Large-Scale Assessments in Education. In Reliability and Validity of International Large-Scale Assessment. IEA Research for Education; Wagemaker, H., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlberg, P. Finnish Lessons 2.0; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner-Khamsi, G.; Waldow, F. PISA for scandalisation, PISA for projection: The use of international large-scale assessments in education policy making—An introduction. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2018, 16, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verger, A.; Parcerisa, L.; Fontdevila, C. The growth and spread of large-scale assessments and test-based accountabilities: A political sociology of global education reforms. Educ. Rev. 2019, 71, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winthrop, R.; Simons, K.A. Can International Large-Scale Assessments Inform a Global Learning Goal? Insights from the Learning Metrics Task Force. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2013, 8, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grek, S. International Organisations and the Shared Construction of Policy ‘Problems’: Problematisation and Change in Education Governance in Europe. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 9, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C. Rethinking the notion of the high-performing education system: A Daoist response. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2021, 16, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.; Sellar, S.; Lingard, B. PISA for Schools: Topological rationality and new spaces of the OECD’s global educational governance. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2016, 60, 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.; Carvalho, L.M. Performance-Based Accountability in Brazil: Trends of Diversification and Integration. In World Yearbook of Education; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Breakspear, S. The Policy Impact of PISA: An Exploration of the Normative Effects of International Benchmarking in School System Performance; OECD Education Working Papers 71; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, K.; Niemann, D.; Teltemann, J. Effects of international assessments in education—A multidisciplinary review. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 15, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.M.; Costa, E.; Gonçalves, C. Fifteen years looking at the mirror: On the presence of PISA in education policy processes (Portugal, 2000–2016). Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, F. Who Is Setting the Agenda? OECD, PISA, and Educational Governance in the Countries of the Southern Cone. Eur. Educ. 2020, 52, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białecki, I.; Jakubowski, M.; Wiśniewski, J. Education policy in Poland: The impact of PISA (and other international studies). Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorur, R. The “thin descriptions” of the secondary analyses of PISA. Educ. Soc. 2016, 37, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C. Tracing the sub-national effect of the OECD PISA: Integration into Canada’s decentralized education system. Glob. Soc. Policy 2015, 16, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemann, D.; Martens, K.; Teltemann, J. PISA and its consequences: Shaping international comparisons in education. Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C. PISA and education reform in Shanghai. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2019, 60, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, D. The OECD and the local: PISA-based Test for Schools in the USA. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2015, 36, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, M. Governing education without reform: The power of the example. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2015, 36, 712–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S. Governing schooling through ‘what works’: The OECD’s PISA for Schools. J. Educ. Policy 2017, 32, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S. PISA for Schools: Respatializing the OECD’s Global Governance of Education. In The Impact of the OECD on Education Worldwide; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, S. Policy, philanthropy and profit: The OECD’s PISA for Schools and new modes of heterarchical educational governance. Comp. Educ. 2017, 53, 518–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S. PISA ‘Yet to Come’: Governing schooling through time, difference and potential. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2018, 39, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S. ‘Becoming European’? Respatialising the European Schools System through PISA for Schools. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2020, 29, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S. PISA, Policy and the OECD. Respatialising Global Education Governance through PISA for Schools; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski, D.; Rutkowski, L. Measuring Socioeconomic Background in PISA: One Size Might not Fit all. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2013, 8, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, D.; Rutkowski, L.; Plucker, J.A. Should individual U.S. schools participate in PISA? Phi Delta Kappan 2014, 96, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.; Lingard, B. PISA for Sale? Creating Profitable Policy Spaces Through the OECD’s PISA for Schools. In The Rise of External Actors in Education: Shifting Boundaries Globally and Locally; Lubienski, C., Yemini, M., Maxwell, C., Eds.; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2022; pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Coburn, C.E. Framing the Problem of Reading Instruction: Using Frame Analysis to Uncover the Microprocesses of Policy Implementation. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2006, 43, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, M.; Olssen, M.E.H.; Peters, M.A. Re-Reading Education Policy; Sense: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sellar, S.; Lingard, B. The OECD and the expansion of PISA: New global modes of governance in education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 40, 917–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B. Digital education governance: An introduction. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 15, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Viana, J.; Carvalho, L. Processos e Sentidos da Regulação Transnacional da Profissão Docente: Uma análise das Cimeiras Internacionais sobre a Profissão Docente (2011–2017). Curriculo Front. 2020, 20, 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.L. ‘Placing’ Teachers in Global Governance Agendas; Centre for Globalisation, Education and Societies, University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2012; Available online: http://susanleerobertson.com/publications/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Addey, C. Golden relics & historical standards: How the OECD is expanding global education governance through PISA for Development. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2017, 58, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auld, E.; Rappleye, J.; Morris, P. PISA for Development: How the OECD and World Bank shaped education governance post-2015. Comp. Educ. 2019, 55, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, D.; Rutkowski, L. Running the Wrong Race? The Case of PISA for Development. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2021, 65, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente, O.; Lee, M. Exploring the OECD survey of adult skills (PIAAC): Implications for comparative education research and policy. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2020, 50, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volante, L. The PISA Effect on Global Educational Governance; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Maroy, C. Comparing Accountability Tools and Rationales. Various Ways, Various Effects. In Governing Educational Spaces. Knowledge, Teaching and Learning in Transition; Kotthof, H.-G., Klerides, E., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Verger, A.; Fontdevila, C.; Parcerisa, L. Reforming governance through policy instruments: How and to what extent standards, tests and accountability in education spread worldwide. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2019, 40, 248–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascoumes, P.; Le Galès, P. (Eds.) Gouverner par les Instruments; Presses de Sciences Po: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, P. Les Politiques Publiques; Puf: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lascoumes, P.; Simard, L. L’action publique au prisme de ses instruments: Introduction. Rev. Française Sci. Polit. 2011, 61, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.L. Maintaining the Frame: Using Frame Analysis to Explain Teacher Evaluation Policy Implementation. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 57, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woulfin, S.L.; Donaldson, M.L.; Gonzales, R. District Leaders’ Framing of Educator Evaluation Policy. Educ. Adm. Q. 2016, 52, 110–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Hutter, I.; Bailey, A. Qualitative Research Methods; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Delvaux, B. Qual é o papel do conhecimento na acção pública? Educ. Soc. 2009, 30, 959–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, J. Conhecimento, Políticas e Práticas em Educação. In Políticas e Gestão da Educação: Desafios Tempo Mudanças; Martins, A.M., Caldéron, A.I., Ganzeli, P., Garcia, T.O.G., Eds.; ANPAE: Campinas, Brazil, 2013; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, D.A.; Rochford, E.B., Jr.; Worden, S.K.; Benford, R.D. Frame alignment processes, micromobilization, and movement participation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1986, 51, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.H.; Kubal, T.J. Movement Frames and the Cultural Environment: Resonance, Failure, and the Boundaries of the Legitimate. In Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change; Emerald Publishing: Leeds, UK, 1999; Volume 21, pp. 225–248. [Google Scholar]

- Benford, R.D.; Snow, D.A. Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2000, 26, 611–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noaksson, N.; Jacobsson, K. The Production of Ideas and Expert Knowledge in OECD; SCORE: Stockholm, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, J. Descentralização, territorialização e regulação sociocomunitária da educação. Rev. Adm. Emprego Público 2018, 4, 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, J. 40 anos: Educação & sociedade seção comemorativa. A transversalidade das regulações em educação: Modelo de análise para o estudo das políticas educativas em Portugal. Educ. Soc. 2018, 39, 1075–1097. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, X.; van Zanten, A. The Social and Cognitive Mapping of Policy, Report; Knowandpol: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, H.T.O.; Nutley, S.; Smith, P. (Eds.) Evidence-Based Policy and Practice in Public Services; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Luke, A. After the marketplace: Evidence, social science and educational research. Aust. Educ. Res. 2003, 30, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rochex, J.-Y. Chapter 5: Social, Methodological, and Theoretical Issues Regarding Assessment: Lessons from a Secondary Analysis of PISA 2000 Literacy Tests. Rev. Res. Educ. 2006, 30, 163–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Role | Portugal | Spain | USA | Brazil | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | |||||

| Idealization Certification | OECD | OECD | OECD | OECD | |

| Funding | Local authorities (Public) | National Authorities (Public) | Edu-businesses Philanthropic foundations US Federal Government (Edu-businesses/ philanthropy/public) | Lemman Foundation (Philanthropy) | |

| National Service Provider | Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon (Public Higher Education Institution) | 2E es (Edu-business) | CTB/McGraw-Hill (2012–2015) (Edu-business) Northwest Evaluation (2015–2016) (not-for-profit organization) Janison (Ed-tech) | Cesgranrio Foundation (R&D) | |

| Authorization | State | State | State | State | |

| Type of Schools | School clusters (Public) | Schools/school clusters (Public/private) | Schools (Public/private) | Schools (Public/private) | |

| Adherent Entities | CIM/CM Participants | Number of Schools per CIM/CM | No of Participating Schools |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIM AVE | 8 | 33 | 28 |

| CIM Médio Tejo | 10 | 19 | 15 |

| CIM Terras Trás-os-Montes | 9 | 12 | 11 |

| CIM Viseu Dão-Lafões | 14 | 35 | 20 |

| CM Amadora | 1 | 12 | 12 |

| CM Arouca | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| CM Barcelos | 1 | 9 | 9 |

| CM Braga | 1 | 14 | 6 |

| Total | 45 | 136 | 103 |

| Category | Subcategory | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic framing (problems) | 1. Schools (and teachers) lack useful knowledge | Probl1 |

| 2. Schools (and teachers) do not collaborate and reflect together | Probl2 | |

| 3. Schools are isolated and lack internal and external articulation and coordination | Probl3 | |

| Prognostic framing (solutions) | 1. PISA tests provide the objective information and expert knowledge | Solut1 |

| 2. PISA-M guarantees working collaboratively and networking | Solut2 | |

| 3. Municipalities ensure effective coordination of the network | Solut3 | |

| Frame alignment (beliefs) | Students can improve their learning outcomes and wellbeing | FrAlign1 |

| Comparisons for improvement promote dialogue and learning, not rankings. | FrAlign2 | |

| Municipalities’ coordination of the network will not affect schools’ autonomy. | FrAlign3 |

| Problems | Solutions |

|---|---|

| Useful knowledge deficit | Adhering to PISA tests (objective data and expert knowledge) |

| Binomial 1—The knowledge deficit is bridged by adhering to PISA tests | |

| Collaboration deficit | Adhering to PISA-M (collaboration and networking) |

| Binomial 2—The collaboration deficit is bridged by adhering to PISA-M | |

| Coordination deficit | Assigning the network coordination to the Municipalities (effective network coordination) |

| Binomial 3—The coordination deficit is bridged by assigning that responsibility to municipalities | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costa, E.; Carvalho, L.M. Framing School Governance and Teacher Professional Development Using Global Standardized School Assessments. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090873

Costa E, Carvalho LM. Framing School Governance and Teacher Professional Development Using Global Standardized School Assessments. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(9):873. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090873

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosta, Estela, and Luís Miguel Carvalho. 2023. "Framing School Governance and Teacher Professional Development Using Global Standardized School Assessments" Education Sciences 13, no. 9: 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090873

APA StyleCosta, E., & Carvalho, L. M. (2023). Framing School Governance and Teacher Professional Development Using Global Standardized School Assessments. Education Sciences, 13(9), 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090873