Abstract

Central to culturally sustaining pedagogy (CSP) is the notion that we sustain what we love by decentering the white gaze. Elevating CSP and the five core social-emotional learning competencies, we honed in on how Black and Brown girls developed knowledge and skills to manage their emotions, achieve goals, show empathy, and maintain healthy relationships within the context of a single-gender summer STEM program. These opportunities to engage in critical conversations to learn, unlearn, and relearn, while showing up as their full and authentic selves, are not often afforded in traditional STEM classes. This paper focuses on dialogue and interactions amongst four program participants—Samira, Rita, Brandy, and Joy. Critical discourse analysis was employed to challenge the dominance and reproduction of discourses by examining social contexts and systemic structures that they addressed in conversation. Findings revealed the importance of cultivating trusting and intentional learning spaces for Black and Brown girls to engage in open dialogue and critique oppressive discourses. It also displayed the significance of leaning into difficult conversations and pluralism to help adolescent girls realize the complexities of culture while also promoting joy and social-emotional development. Creating spaces that affirm Black and Brown girls matter; their contributions and work that they do matter.

1. Introduction

“Even when your voice shakes, speak up and show up in your most authentic way. Your voice matters in this world. When this world tries to discredit you, just link arms with your sisters and show them that Black girls do matter.” These words are taken from Marline Francois-Madden’s guide for creating safe spaces for Black girls [1]. She discusses the beauty of sisterhood and creating healthy friendships that challenge Black girls to become better versions of themselves. This notion of speaking up and showing up in an authentic manner is the Black-girl-centered experience that Ruth Nicole Brown titled—Saving Our Lives Hear Our Truths (SOLHOT) [2]. SOLHOT is a political project that embraces the paradoxes and truths emerging from the celebration of Black girlhood. Black girls are often misunderstood, silenced, adultified, hypersexualized, and ignored [3,4]. Cultivating sacred spaces where Black girls are centered, their experiences valued, and their voices heard are essential to changing the narrative. This is particularly important if we seek to transform harmful narratives about what it means to be a Black girl in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

The literature indicates that Black girls are interested in science, but often feel unwelcomed or experience racism and sexism in the classroom [5,6]. They are acutely aware of these inequities and biases and acknowledge the role that their multidimensional identities have played in formal school [7,8]. Furthermore, Black girls who identify as high-achieving are often disadvantaged by their teachers and school counselors who have lowered expectations for their academic success and underestimate their potential [9,10]. “When gender and skin color are the major factors determining who will do science, a considerable amount of scientific talent is lost” [7].

In exploring representation in the STEM workforce, a greater share of men (29%) than women (18%) work in STEM occupations [11]. This same report indicated that Asian populations occupy the highest share employed in STEM disciplines (39%), whereas Black workers were among the lowest (18%). While all racial groups experienced growth in the STEM workforce, the number of women remain fewer than that of men. These statistics emphasize the double bind of being a woman of color in the STEM fields, and a Black woman in particular [12,13]. While this paper does not specifically address what it means to be a Black girl in science learning spaces or even the plight of Black women in the STEM workforce, we describe how the use of culturally sustaining pedagogies (CSPs) and social-emotional learning within a counterspace has the potential to promote adolescent development amongst Black girls [14,15]. In that regard, we asked the following research question—How do intentional and culturally sustaining social-emotional development lessons influence out-of-school STEM learning spaces for Black and Brown girls? A sub-question seeks to understand the discourses that Black and Brown girls employ in reflecting on assessment data about the academic performance of eighth-grade girls.

2. Conceptual Framework

Within the context of the United States and other nation-states living with the legacies of genocide, land theft, enslavement, and various forms of colonialism, state-sanctioned schooling for Communities of Color has been geared toward advancing assimilationist and often violent White imperialism. Practices in many formal educational structures have required students and families of color to abandon or divest from their languages, literacies, cultures, and histories in order to experience success [14]. CSP envisions education beyond the lens of long-standing oppression and subjugation. It draws inspiration and insights from generations of community-driven revitalization, resistance, and revolutionary love, despite enduring brutality [16]. CSP asks us to reimagine schools as sites where Whiteness is decentered, and diverse pluralistic cultures are valued and sustained. It enables us to recognize the flawed approach of evaluating ourselves and the youth in our communities solely based on White middle-class standards of knowledge and behaviors that still hold sway over the concept of educational achievement [14]. Students of Color enter into our classrooms with a sense of wholeness, possessing an understanding of their identities and values. However, the white gaze often undermines their brilliance by adopting a deficit lens. CSP advocates for an emancipatory vision of education that moves beyond scrutinizing students and directs critique toward oppressive systems and structures [14,16].

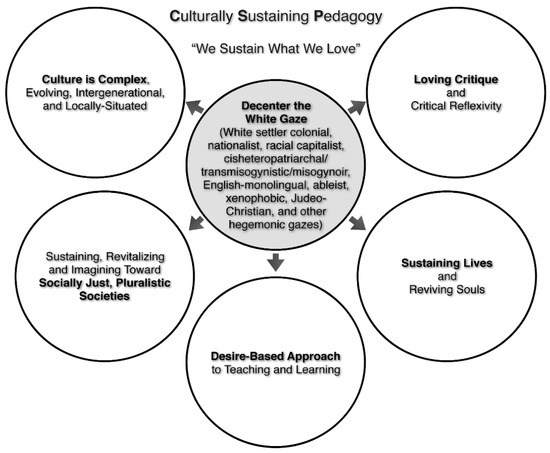

The divide between educational institutions and the students with whom they are supposed to serve continues to grow because their identities, experiences, and cultures are not affirmed through the curriculum and pedagogical practices [14,17]. CSP as a theoretical lens builds upon the principles of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy—students must (1) experience academic success; (2) maintain their cultural competence; and (3) develop sociopolitical awareness and critical consciousness. It provides a space for researchers and practitioners to develop a teaching approach that embodies resistance and encourages “marginalized communities to fight for their linguistic and cultural sovereignty” [18]. The six central tenets of Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy are displayed in Figure 1 [19]. CSP aims to (1) decenter the white gaze; (2) recognize that culture is complex, evolves through time and context, and is intergenerational; (3) push us to engage in loving critique and critical reflexivity in theory and practice to hold ourselves accountable when we may unintentionally perpetuate oppressive structures through discourse and action; (4) embrace and elevate socially just pluralistic societies; (5) approach teaching and learning with love for ourselves and our students while making time for joy; and (6) sustain and revive the souls of students and communities in the educational survival context where students are vulnerable to spirit murdering [20,21].

Figure 1.

Tenets of culturally sustaining pedagogy.

3. Social-Emotional Development

In considering pedagogical practices that are humanizing to sustain who and what we love, our conceptual lens includes a focus on social-emotional development (SED). Although SED and social-emotional learning (SEL) are often used interchangeably, we position SED as an umbrella term that incorporates the widely accepted label of SEL and related terms, including 21st-century skills, workforce skills, life skills, or non-cognitive skills [22]. We emphasize development because it encompasses learning and thriving throughout one’s lifespan, incorporates students’ lives outside of school and youth development programs, and recognizes that children develop sets of SEL skills at different times.

SEL is a process of gaining the knowledge and skills to manage emotions, achieve goals, show empathy, and make responsible decisions to build the capacity for establishing and maintaining healthy relationships [15,23]. According to Jones and Doolittle, “SEL skills may be just as important as academic or purely cognitive skills for understanding how people succeed in school, college, and career” [24]. We employ the five core SEL competencies outlined by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) with an understanding that they develop overtime, and then hone in on the process by which this occurs within the context of a single-gender summer STEM camp. These core competencies include self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision-making, relationship skills, and social awareness [15]. Self-awareness is one’s ability to understand their emotions, thoughts, values, and experiences. It also includes the ability to recognize one’s strengths and areas of growth. Self-management focuses on the ability to regulate emotions, thoughts, and behaviors, including the ability to manage stress, delay gratification, and be organized. Responsible decision making is the ability to make good choices while considering personal goals, moral and ethical standards, and being able to weigh the pros and cons of a decision. Relationship skills enable people to build and maintain positive and supportive relationships. This also means that they can communicate clearly, work collaboratively, and consider the needs of others. Finally, social awareness is being able to show empathy and valuing different perspectives. More specifically, social awareness is the ability to understand people and experiences from diverse backgrounds and cultures [15,23].

In a study conducted to test the CASEL model in a normative adolescent sample using confirmatory factor analysis, researchers determined that relationships were significant and this multidimensional model was valid in explaining outcomes [25]. They also observed that an improvement in one dimension is believed to enhance improvements in other dimensions, either due to shared foundational skills or increased opportunities for positive skill development. The study findings demonstrated the validity of the SEL dimensions in explaining functioning. However, further research is necessary to understand how the relationships between these dimensions evolve throughout development [25]. Our research explored the SEL core competencies and emphasized development by analyzing how Black and Brown girls expressed and self-regulated their emotions and behaviors during their participation in a summer STEM program. We attended to interpersonal and intrapersonal skills that they leveraged to navigate social interactions and adapt to various daily challenges and demands. This included their ability to understand, regulate, and express emotions in age-appropriate ways [22]. In the summer program, we intentionally and explicitly incorporated SED into the curriculum to provide a space for Black and Brown girls to explore various academic topics while also considering social and historical contexts, STEM identity, and the value of community. SED is important for understanding strengths and weaknesses associated with academic achievement and also supports students’ mental health [22]. For Black and Brown girls who may be overlooked in their traditional STEM classes or not provided with opportunities to engage in critical conversations to learn, unlearn, and relearn, this program sought to offer a space where they could be their full authentic selves.

4. Merging CSP and SED

Our research put the central tenets of CSP in conversation with the five core SEL competencies to support adolescent development [14,15]. Black and Brown girls were at the center of this study. Therefore, we had an explicit goal of decentering the white gaze to create a counterspace where the girls could thrive. Counterspaces are places where deficit notions of People of Color can be challenged and where positive climates can be established and maintained [26]. The following CSP tenets were central to the study and are explained below:

- Sustaining Lives and Revitalizing Souls: Spirit murdering is the personal, psychological, and spiritual injuries to People of Color through structures of racism, privilege, and power that systemically deny inclusion, protection, safety, nurturance, and acceptance—all things a person needs to be human and to be educated [20]. By sustaining lives and revitalizing souls, we actively work against the spirit murdering that Students of Color are subject to within the educational survival complex to intentionally create safe spaces [14].

- Loving Critique and Critical Reflexivity: By creating a space that intentionally sustains and revitalizes learners, we not only promote educational success but also contribute to the overall well-being and flourishing of marginalized individuals and communities. Our focus on building authentic relationships enables us to engage in thoughtful reflection and constructive dialogue, allowing us to challenge each other when we are perpetuating harmful language and deficit ideologies toward our own and other communities. By doing so, we cultivate an environment that fosters personal and collective growth, nurtures inclusive practices, and promotes social justice.

- Culture is Complex, Evolving, Intergenerational, and Locally Situated: Culture is complex and multifaceted, encompassing a wide range of beliefs, values, practices, and traditions that are shaped by historical, social, and political contexts. It is important to recognize that culture is not static but instead evolves and changes over time. We aimed to create a learning environment that values and celebrates different cultural perspectives, promotes intercultural understanding, and encourages critical reflection and dialogue.

- Sustaining, Revitalizing, and Imagining Toward Socially Just, Pluralistic Societies: The ultimate goal is creating communities where all individuals are valued and respected, regardless of their backgrounds or identities, and where everyone has access to equal opportunities and resources. Social justice is an ongoing process that requires ongoing attention and action.

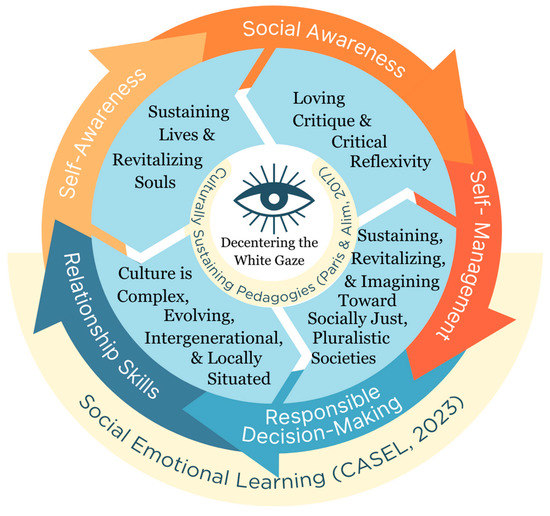

We selected four components of CSP and five SEL competencies in this study to promote adolescent development. See Figure 2 for a visual representation of our conceptual framework [15].

Figure 2.

Merging culturally sustaining pedagogies and social-emotional learning toward adolescent development.

Researcher Positionalities: This study was conducted by three scholars who identify as Black women or Afro Latina. We had varying entries into education serving as former elementary, middle, and high school teachers.

Natalie: As a Black woman science education researcher, I am deeply vested in providing inviting spaces for Black and Brown children to learn, grow, and be their full selves. Of particular interest is how to nurture and support Black girls who have been excluded, marginalized, and overlooked. I am the founder and executive director of I AM STEM and principal investigator of the larger project that serves as the context for this research study. I partner with community-based organizations and help build their capacity to offer high-quality programs through professional development and curricular resources. I am committed to elevating the voices of Black girls and generating new narratives of their STEM learning experiences in our academic journals and spaces. For this study, I established a partnership with a youth-serving organization that provides programming for girls and created a non-residential summer day camp on the university’s campus for their participants. I assisted with organizing the program alongside Laura and Shae, co-developed the curriculum, and oversaw the research process.

Laura: I position myself as a cis-gendered Afro-Latina and a daughter of hard-working immigrant parents. I particularly remember my middle school science classes. My science teachers required us to read the textbook and to answer the questions at the end of the chapter, making sure we took the time to list and define every vocabulary word in the text. I hated science…I considered science dull; a subject of rote memorization with no real connections to my lived experiences. Within the walls of my very own science classroom, I created a safe space that blossomed into a thriving classroom community where love was etched into my lessons. My own personal and educational experiences position me as emic to my work. I am committed to ensuring my students’ middle school science experiences do not mirror my own, and am compelled to work toward an equitable STEM education where Black and Latina girls see themselves in the curriculum. I was a co-organizer for the camp that serves as the context of this study and helped to plan and implement many of the STEM camp activities.

Shae: I am a Black woman interested in exploring the experiences of Black students, families, and communities in urban settings. As a native of Atlanta, Georgia, I firmly believe in the power of Black communities in helping to create support systems that counter the barriers that students face. My previous experience as an urban elementary school educator has informed my thinking regarding the importance of catering to the needs of the whole child—mental, physical, and emotional. I understand the significance of Black educators who lead with love, understanding, and an unwavering will to fight for their students. For this study, I served as one of the co-organizers who helped develop the curriculum and facilitate lessons.

Collectively, our stories, experiences, and expertise shaped the implementation of the STEM program, development of the research study, and interpretation and presentation of the findings.

5. Literature Review

We discussed CSP and SED at length in the conceptual framework section, and so the literature review provides a brief overview of informal learning environments and studies that have explored programs for Black and Brown girls. We emphasize STEM camps and initiatives housed in community spaces and on college campuses. This abbreviated review is concluded by the identification of an important gap in the literature around culturally sustaining SED for Black girls and its potential for moving STEM education forward.

Research shows that schools can be violent and dangerous places for Black girls, and they are more likely to experience corporeal punishment and exclusionary disciplinary practices [27,28]. In many contexts, Black girls are considered too mouthy or loud with bad attitudes, and their voices are often unwelcomed in formal schools. These negative perceptions of Black girls are rooted in historical stereotypes [29]. While formal schools have not been welcoming to many Black girls, there are extracurricular and out-of-school time programs where they experience academic achievement, have increased social outcomes, and can show up as their full and authentic selves.

Across racial and gender lines, children are becoming more involved in afterschool and summer programs, making informal learning experiences an important lever to the comprehensive improvement in STEM education [30,31]. Informal learning environments, sometimes referred to as out-of-school-time programs, are defined as programs that provide students with exposure to academic experiences outside of a traditional school setting. Research shows that increasing access to informal science and mathematics programs directly impacts learning that takes place in school [31]. General features of informal STEM education are that learning is personal, contextualized, voluntary, and driven by the students’ interests [32,33]. These low-stakes environments can be student-driven and self-directed where children can focus on becoming science learners and not on getting the correct answers. Effective out-of-school STEM programs engage young people intellectually, academically, socially, and emotionally; provide firsthand experiences of phenomena and materials; and engage youth in sustained STEM practices. However, opportunities to participate in informal science programs have disproportionately excluded Black and Brown students due to affordability and accessibility due to location [34,35]. Broadening participation efforts are being enacted to diversify the students who participate in these programs as well as the educators and facilitators in these programs [31].

In terms of Black girls and women, research reveals the effectiveness of STEM programs in enhancing participants’ aspirational, social, and familial capital [36]. Additionally, out-of-school programs provide access to role models, expose students to career pathways, increase their sense of belonging, and support the overall persistence of Black girls and women in STEM [36]. These programs must be in spaces that affirm their identities and cultural referents to improve the learning experiences of Black girls. Programs such as the Girls STEM Institute (GSI) revealed an increase in Black girls’ mathematics and science self-efficacy and value of STEM knowledge [37]. Anissa, a participant in the study, shared how her spirit was broken in school when a trusted teacher stated, “You do know no college is going to accept you.” In a study exploring the intersections of giftedness and Black girlhood, a participant Nickiesha stated, “the problem with identifying gifted Black girls is that teachers don’t believe we exist” [9]. The author argued that the talent development of Black girls requires us to create safe spaces, antiracist policies, and curricula that are reflective of their identities.

Negative messages questioning the intelligence of Black girls have been attributed to lowered beliefs in their own abilities to be successful. It is essential to confront the harmful effects of spirit murdering perpetrated by adults and authority figures, explore strategies for establishing more nurturing and inclusive environments in schools, and recognize the pivotal role educators and program directors play in validating the cultural resources and exceptional abilities of Black girls [38].

Another important outcome of informal spaces is the humanizing effect it has on girls’ STEM identity development [39]. Middle school can be a fragile time for girls as they transition from one stage of development to the next. This is also a time when their interests and self-esteem begin to see a shift, and developing positive STEM identities could have some long-term effects. In tending to their developmental needs, it is critical for adults to create learning environments that foster social-emotional learning where students’ individual backgrounds and cultures can be infused into lessons. They should have space to express a full range of emotions, and feel safe, cared for, and respected in the learning environment [40].

In a study to explore the relationship between humanity and mathematics teaching and learning, researchers conducted interviews with middle and high school girls and found that their perceptions of themselves and the teaching practices they encountered largely influenced their mathematics learning experiences [41]. The authors also noted that girls need to be viewed holistically and educators must be equity-minded to provide them with relevant experiences. When educators and instructors acknowledge the barriers that girls face in traditional STEM settings and actively work to recognize their backgrounds and experiences to engage the whole child, that promotes humanizing instruction and inclusive learning environments. We must address the underrepresentation of girls and women in STEM, as they bring invaluable perspectives and creativity to these fields. By focusing on culturally sustaining lessons and fostering social-emotional development, we can empower girls to thrive and excel in STEM education.

6. Research Context

This research is part of a larger study exploring the STEM identity development of Black girls as they matriculate through middle and into high school. It is a research–practice partnership between an institution of higher education and a youth-serving nonprofit organization that equips girls with the skills to navigate through economic, gender, and social barriers.

We specifically partnered to support one of their signature programs to broaden girls’ future academic and career interests, encourage enrollment in advanced mathematics and science courses, promote positive risk-taking, and assist in developing networks of peers and mentors to support their future endeavors. Our specific role was to build girls’ confidence and skills through hands-on opportunities in the STEM disciplines. Participants in the program live in different communities within the metropolitan area and represent various schools. During the school year, we host monthly activities focused on strengthening their knowledge in STEM subjects and careers, personal development, and overall wellbeing. The context for this study is situated in Year 1 of the program and research–practice partnership during the 4-week summer camp that was held in June 2022.

“Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.” These words by the late Congressman and Civil Rights leader John Lewis serve as a guiding principle encouraging each generation to engage in continuous action toward freedom and a more just society. In summer 2022, we connected an excerpt of this powerful slogan with Disney’s Encanto movie and designed a summer program around a theme that bridged activism, enchantment, and STEM—“Encanto: Good Trouble, Necessary Trouble.” Encanto shared the story of the Madrigal Family who fled an armed conflict in their town and lived hidden in the mountains of Columbia. The plot uncovered how each child received a unique gift except for the protagonist Mirabel who was devoid of any special gift but became the miracle that saved the family. Instead of getting lost in a sea of despair, she was determined to help her family keep the miracle and engaged in good and necessary trouble. Camp organizers incorporated the urgency of civil and social movements with life lessons presented in the movie. The design and implementation of the program tapped into the interests and humanity of Black and Brown girls.

7. Participants

This study’s participants were rising eighth-grade girls enrolled in I AM STEM Camp in collaboration with the youth-serving organization and institution of higher education. The 4-week summer program was housed at the university. We applied a purposive sampling approach and four of the program’s 19 participants are included in this paper—Samira, Rita, Brandy, and Joy. These participants were selected because excerpts of their exchanges were analyzed and extracted to provide insights on how the girls responded to the incorporation of CSP and SED in the curriculum. See Table 1 for basic demographic information. All four participants attend various public schools within the metropolitan area.

Table 1.

Participants in I AM STEM Camp.

Samira describes herself as kind, loving, outspoken, trustworthy, and elegant. She is proud of her Indian culture and loves to wear traditional clothing. Samira plans to pursue Business and Law. She takes pride in her skills in dancing, playing the bass, and planning parties. Samira is outspoken within the group and loves to play an active role in all of the program activities. Samira shared how she helped to design a website for her mom’s catering business and used this skillset to assist the girls in their website’s design this summer.

“My culture is very important to me. And the reason I value it is because everything is so diverse and my Indian culture has so much to offer.”—Samira, student reflection post, 27 June 2022.

Rita describes herself as driven and hardworking. She is compassionate and values her family and their stories. She loves R&B music and dancing. Rita wants to pursue engineering or computer science because she enjoys and excels in math, science, and social studies.

“Hi, my name is [Rita] and I was born and raised in Baltimore, Maryland. When I was 7, I moved to Georgia for better opportunities because the schools in Baltimore were not the best. So when I moved to Georgia I was a year behind the other kids. I persisted through the trouble. I got into this program and have good grades, especially A’s.”—Rita, student reflection post, 27 June 2022.

Brandy describes herself as funny, respectful, responsible, mature, and talkative. Brandy loves puzzles and enjoys playing tennis and watching TV. Within the group, Brandy is unapologetically herself and open-minded. Brandy wants to become a forensic scientist, and she is talented at math and cooking.

“I value my friendships and honesty.”—Brandy, student reflection post, 27 June 2022.

“I would describe myself as intelligent, socialite, respectful, responsible, mature, enthusiastic. I am [of] Jamaican descent [on] my mother’s side… Both my parents are from New York.”—Brandy, individual interview, 17 September 2022.

Joy describes herself as loud, outgoing, funny, and lit. Outside of school, she loves to hang out with her friends and play volleyball. Joy is outspoken and enjoys helping to lead brain breaks. She also helped to choreograph a dance for the culminating ceremony at the conclusion of the summer program.

“My family and friends are most important to me. Plus volleyball. I value these things because family will always be there for you and volleyball keeps me calm. It’s my happy place.”—Joy, student reflection post, 27 June 2022.

This paper focuses on separate dialogues and interactions between Samira and Rita and Brandy and Joy. We learn more about who they are within the context of critical conversations in lessons that leveraged and embraced tenets of CSP to decenter the white gaze.

8. Methodology

This study’s research design sought to answer how the intentional and culturally sustaining SED lessons influenced out-of-school STEM learning spaces for Black and Brown girls. We employed critical discourse analysis (CDA), which was designed to analyze the language use of those in power, how discourse produces and reproduces social domination, and the ways that hegemony is resisted [42]. Educational research has turned to CDA as an approach to examine the relationship between language and society because it bridges the analysis of micro-level social ordering such as language use, discourse, and verbal interaction, and macro-level social ordering such as power, dominance, and inequality [43,44].

CDA looks at power as control and asks three interrelated questions regarding discursive power:

- How do powerful groups control the text and context of public discourse?

- How does such power discourse control the minds and actions of less powerful groups, and what are the social consequences of such control, such as social inequality?

- What are the properties of the discourse of powerful groups, institutions, and organizations and how are these properties forms of power abuse?

Scholars who utilize CDA separate themselves from other critical work by stating their analysis works beyond description into interpretation as well as examining the social world and how language is used [43]. The starting point of CDA begins with the location of power in the area of language as well as understanding, uncovering, and transforming conditions of inequality [43]. CDA does not adhere to a specific set of formal steps, but those who employ this methodology examine how discourse functions in perpetuating or challenging power dynamics [45]. This analysis involves investigating diverse textual elements such as setting, access, speech acts, perspective, syntax, and style [45].

We embraced a methodological framework that incorporates characteristics and processes pulled from a network of CDA scholars [46]. First, we selected the discourses and ensured that they were related to injustice or inequality in society. This step helped to reorient ourselves with the contexts of the conversations. Included in our data sources were audio transcripts from several classroom discussions as well as written artifacts from reflection exercises. We uploaded the transcribed sources to NVivo to begin the analysis process. Using an inductive approach, we first reviewed the tenets of CSP and SEL competencies toward adolescent development that made up our conceptual framework. Before conducting the coding process, we engaged in discussions to ensure that everyone involved had a mutual understanding and consensus regarding the meanings of each tenet. Once the tenets and their definitions were set, we created a codebook inclusive of initial codes to help guide the process (see Appendix A).

After locating and preparing data sources to construct our database, we explored the background of each text to examine the social and historical context and producers of the texts. Next, we coded texts, identified overarching themes, and then identified major themes and subthemes using a choice of qualitative coding methods. We analyzed the external relations in the texts (interdiscursivity) to investigate how the texts affect social practices and structures and how social practices informed the arguments produced. We then analyzed the internal relations in the text by paying close attention to the language for indications of what the texts set out to accomplish and representations of social context, events, and the speakers/authors’ positionality. Finally, we interpreted the data for meanings of the major themes, external relations, and internal relations.

CDA is helpful in understanding how groups reproduce or resist power, dominance, and inequality through discourse; this required researchers to uncover the ideologies that led to the reproduction or resistance of subjugation [47]. During our time together in the summer of 2022, we intentionally cultivated a learning space that elevated the stories of Communities of Color by marrying CSP and SED. Once the initial coding was complete, we collaborated and discussed our findings to uncover repeated themes. During these discussions, we also developed several codes not included in our initial discussion. Next, we decided whether any themes overlapped and could be grouped.

In alignment with CDA, researchers examined social relationships that impacted the production of certain discourses and analyzed internal relations [46]. As we examined the themes, we considered the social contexts and systemic structures that helped produce some of the conversations between the girls. During the analysis, we encountered certain tenets that were particularly prominent, leading us to contemplate the girls’ social backgrounds, socioeconomic status (SES), and racial composition. This consideration allowed us to gain deeper insights into the discourses at hand. After thorough conversations about the interpretation of the data, initial themes, external and internal relationships, and final themes, we developed our findings.

9. Findings

The findings section presents excerpts of dialogue exchanges between Samira and Rita and Brandy and Joy. To honor the voices of our participants, we did not correct grammar or remove idiosyncrasies. The summer STEM program incorporated 4 weeks of activities and interactions. Yet, we chose to focus deeply on one lesson and how we created spaces that were conducive for critical discourse through the implementation of intentional and culturally sustaining SED lessons for Black and Brown girls. The two major themes that emerged from this study were (1) the importance of cultivating trusting and intentional learning spaces for Black and Brown girls to engage in open dialogue to critique and challenge oppressive discourses; and (2) the significance of leaning into pluralism and difficult conversations to help adolescent girls realize the complexities of culture while also promoting joy and social-emotional development.

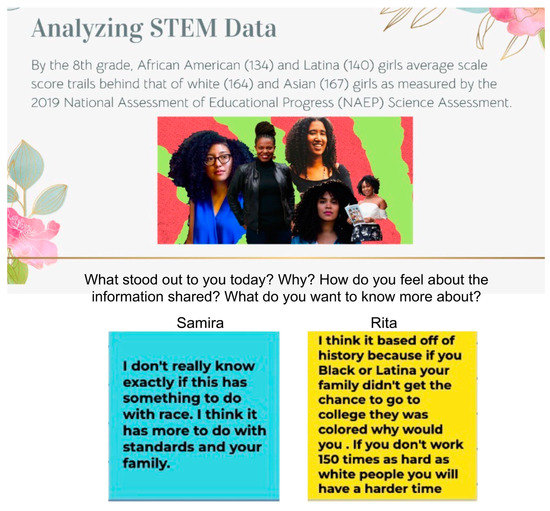

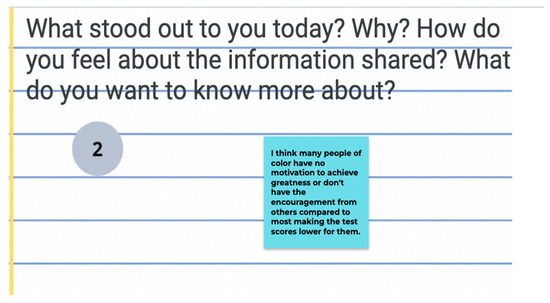

Loving Critique and Reflexivity (CSP): By building trusting and intentional learning spaces, the girls engaged in open dialogue and provided loving critique that challenged discourse that perpetuated racialized and gendered oppression. During this particular day at camp, Laura and Shae facilitated a STEM activity and conversation around girls’ achievement in science. They analyzed data on the representation of girls in science that was disaggregated by race and ethnicity. This led to lively and thought-provoking conversations amongst the girls. Of particular interest was dialogue generated as they analyzed the 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Science Assessment scores. Laura shared the prompt and students reflected on what stood out to them during the session, their reactions to the presented information, and any areas they would like to explore on a deeper level. See Figure 3 for Rita and Samira’s jamboard responses followed by an excerpt of their exchange.

Figure 3.

Samira and Rita reflect on STEM data.

Laura: By the 8th grade, African American and Latina girls’ average scale scores trails behind that of white and Asian girls as measured by the 2019 National Assessment for Educational Progress Science Assessment. I want you to think about that and then reflect on your jamboard. Whenever you are ready to share out, we can do share outs. How do we feel about this data point?

Rita: Um, I’m not 100% sure if it’s about race but it could be. It’s because I know that like right now where we’re living, it’s like… I know that I have the same chance as some of my white friends- even a better chance because of different things that I did to help myself to get ahead of people knowing that I am a woman and I am Black but I know that some African Americans, their parents didn’t go to college and they’re not financially stable so they can’t provide them with the same help, opportunities and help like someone that’s White.

Samira: I’m still like confused, clearly African Americans and Hispanics are scoring lower than the Whites and Asians but what does race have to do with school? And like studying? Like yeah you can get racially discriminated at school but like this is an assessment. This is a test that they are taking. How does race kind of portray into that? You know? Are people making sure on purpose that they get bad scores or like, this is not a lie, this is literally what’s happening, so I’m confused, I don’t how race fits into all of this.

Rita: I want to answer her question. It has to do with the history because if my great grandma didn’t go to college because she didn’t have the opportunity, and she didn’t grow up with a lot of money and she was trying to work hard to get the money and then she had a child and she didn’t have the opportunity to go to college because her mother didn’t have the opportunity to give her the resources that she needed. And then you go to her child, she went to college because her mother had the opportunity and pushed her really hard and made sure she did something with sports she got good grades but she still didn’t really…she went to college because she worked hard for it but at the same time she’s still a Black woman in America and yeah she went to college and got this and that but she’s still Black and she doesn’t have those same opportunities as White women. Because I know, one of my teachers told me, she said that it was 2009 and that’s when I was born, and she was in high school and she used to get made fun of because she had Black friends so why would you getting made fun of for talking to a Black person. How would a Black person or a Latino in general or a person of color be able to have those same opportunities based off of the history. And then you go to our generation, we have better opportunities because I know that my great grandma, my grandma, and my mother fought for these opportunities but at the same time, I’m still a Black woman in America and I’m still being racially discriminated, racially profiled and I still kind of still have that edge on test score because I know maybe their great grandparents owned slaves or was selling slaves so they have that money and then that money’s going down to the generation and then they’re financially stable enough to go to college easily without working as hard and doing this and that so it does have something to do with race because of the history of everything.

Intentionally cultivating a learning community that welcomes loving critique provided a safe space for Samira to express her dissenting views, which were met with resistance from Rita. Subsequently, Rita took the initiative to elucidate her perspective by drawing on her own lived experiences, thereby offering Samira an enhanced understanding of her position. Samira’s position was that race did not influence the discrepancy in test scores amongst eighth grade girls across racial and gender lines; she attributed it to familial standards, whereas Rita discussed the importance of considering historical underpinnings and the residual effects across generations. She specifically shared how her mother, grandmother, and even great grandmother had to fight for opportunities and if you are a Black woman in America, you will experience racial discrimination and racial profiling. Samira asked a provocative question that must be given consideration—“what does race have to do with school?” She was perplexed by the role of race on what was supposed to be a standard assessment. Standardization must be critiqued because there is a human factor involved that cannot be ignored. Rita discussed the history of enslavement and how that would come to bear during assessments because of the daily torrents that Black girls and women face. Rita wrote on the jamboard that Black girls and Latinas must work 150 times as hard as White people to experience success. She also made connections to generational wealth and how financial stability influences one’s academic outcomes.

We shift our attention to an exchange between Brandy and Joy in response to the NAEP data. This dialogue focused less on the standardization of assessments and historical factors to the role of motivation.

Brandy: Um, I think with the whole test scores thing, I think many People of Color have like no motivation to like achieve greatness ‘cause they have this type of idea…Because they have this idea that they’re never going to like succeed in like the science field or like they’re not getting the right motivation compared to the other girls like White and Asian, you know?

Laura: So you think that Black and Latina girls have less motivation?

Brandy: Mhm.

Laura: Why do you think that they have less motivation?

Brandy: I mean, I don’t know ‘cause like there could be like a um…like oh you need to get a real job or that you’re not gonna make it in this certain type of field so why try doing it, you know? ‘Cause like I know like sometimes like they’re always like oh follow the family business or something like that or getting a job that pays good money or something like that so there’s no point in trying anymore, you know?

Laura: Okay, what are our thoughts on that y’all?

Joy: On what she said?

Laura: Mhmm.

Joy: I feel like she…no…just shut her down. I feel like what she really meant to say was that Latina and African American girls aren’t getting the right MOTIVATION.

Me: So what’s the difference, Joy?

Brandy: What IS the difference?

Laura: Pause, this is a safe space too y’all, so we won’t judge you no matter what you say in this space. Alright Joy, what’s the difference between not getting the right motivation and not being motivated?

Joy: Not being motivated means you don’t want to do it, like okay it’s there…I don’t want to do it though. And then getting the right motivation is like…they’re telling you you can’t do something.

In the course of a group discussion, Joy held a perspective that was in stark contrast to that of her peer, Brandy. However, despite this disagreement, Joy demonstrated an admirable display of patience by allowing Brandy to fully express her viewpoint before contributing her own insights. It should be noted that Brandy is Black with Jamaican heritage and Joy is African American. As they engaged in dialogue, their cultural histories and upbringing informed their vantage point and analysis of the STEM data presented. Brandy shared that it may be a lack of intrinsic motivation that hindered the success of Black and Brown girls, whereas Joy determined that they were not receiving the right kind of support. Laura served as a facilitator and reminded them to pause as it was a safe space for them to express altering opinions. It is noteworthy that the conversation, while discussing potentially contentious issues, was conducted in a lighthearted manner, characterized by jovial exchanges rather than harsh debates. This is indicative of a healthy and productive group dynamic, which fosters an environment that is conducive to promoting a wide range of diverse ideas and perspectives.

Sustaining Lives and Reviving Souls (CSP + SED): The significance of leaning into pluralism and difficult conversations to help adolescent girls realize the complexities of culture while also promoting joy and social-emotional development. Rita discussed her own experiences with the school system growing up in Baltimore before moving and the realities that she would face should she pursue a college education.

Rita: Like, I know, because I moved from, I moved here from Baltimore and they didn’t really teach me math or nothing like, there was no math class, there was no ELA class, we just did science experiments and read books like that’s the only thing so I know that I have to study harder. I know that I have to read more books. I know that I have to…

Laura: You had to take initiative to do more than is what you’re saying?

Rita: I’m already behind! So I knew that my mother had four kids, I know that she can’t just pay for college back to back like that. I knew that I had to do even more for scholarship opportunities and like to get a good career because college is expensive.

Laura: So you felt like you had to do more, do you feel like you’re in a better school now than in Baltimore?

Rita: Yes.

Laura: Why do you think that your school didn’t offer those things?

Rita: It was a Black community, the school I think it was 100% that was Black. I’m pretty sure and if it wasn’t Black they were still of color and I feel like we’re in the hood, we’re in the ghetto like what are these children gonna do? What, they’re gonna make it out the hood? No, we’re just not gonna give them the resources that they need to teach these students.

Laura: So you think that students of color were being limited, their resources were being limited because of racial reasons. So it’s not on the kids?

Rita: No.

Laura: It’s not on their families…it’s on? The school structure what you’re saying?

Rita: That’s what I think at least.

Laura: Yeah, I mean, and what you think is important.

Samira: Yeah so…I don’t think this has to do anything with race and the reason I think that is because…these, all these girls in the same grade so that means that they were given the same amount of knowledge and they’ve all been taught the same thing.

Laura: Are you sure?

Samira: Unless one of them, like Rita said, doesn’t go to a school like that which could be the case but…it’s like most of these girls probably have learned the same curriculum, since they’re all in the same grade but at the end of the day some got better grades than others. And like she was saying, it could be that some of these girls were not brought up in good schools and they were brought up in a bad community which led them to not scoring [like] people who were brought up in a good community because I…I don’t want this to come off as racist but like if you think about it… you’ve never seen like…yes, I’m not saying that there aren’t but most of the time White people are educated people who have good money, can provide their children with opportunities they want while on the other hand while colored people we don’t have that. That’s an opinion of mine.

(Additional conversations)

Samira: Because if you think about it, not all these girls but pretty sure that 20% or 30% of these girls are most likely taught the same exact curriculum but also what Rita was saying, some schools don’t provide you with the resources that you need comes back to the fact it has nothing to do with the girls itself and their race I feel like, I feel like it has more to do with what they are given to learn and the opportunities and the school.

Rita: I think it’s about the system. I think it’s the system.

(Additional conversations)

Samira: Yeah, so there’s actually a whole caste system in India, it’s like people who are farmers and stuff, they don’t get the opportunities and then it’s like warriors and then the highest is like people who own businesses and then rich wealthy people so I go to India every year and I see that pretty much it’s like how like I feel like we are so stereotyped to be smart and everything but it’s really not like that at all, like yeah sure people in India are smart but have you seen the stuff they go through? My cousin, his family is not rich at all, my dad had to buy him a computer for college so that he could study, his family can’t even afford that but he worked hard and he did everything and now all the way from India someone who has no money at all, he’s coming to [university] to study for his masters so I feel like it just really depends on how you take it. If you work hard and you try your best, you can make it happen.

In this conversation, Laura asked clarifying questions so that the girls and facilitators could understand each person’s stance. Laura also validated their thoughts and created a space that was conducive to sharing stories and hearing different perspectives. In Rita and Samira’s conversation, there was an underlying theme of the need to work hard in order to be successful. Rita discussed how Black/Latina girls and women have to work harder than White people and Samira complicated this conversation with her discussion on the role of class and poverty. Rita acknowledged potential gaps in her education that required her to read more and apply herself in school—simply to function on grade level. Furthermore, she discussed having three siblings and, to make college a reality, Rita would need scholarships and financial support. Rita utilized language such as “make it out the hood” to describe how structures, institutions, and systems keep families entangled in this cycle that make it difficult to get out and experience new realities. Rita also explained that withholding resources from schools serving predominantly Black and Brown students is strategic and intentional in order to perpetuate existing systems.

Samira struggled to understand the role of race because if the girls in the NAEP report were all in the same grade level, they should have been taught similar things, and therefore have the “same amount of knowledge.” This disregards factors such as the conditions of the schools and curricular materials, teacher effectiveness and qualifications, and many other considerations. While Samira minimized the role of race and racism, she shared comments that she hoped would not “come off as racist.” She began to grapple with what it means to grow up in a “bad community” and how White people are educated and have “good money.” What does it mean to label one’s community as bad and who gets to assign this categorization? Samira continued to disregard race as a mitigating factor in formal schools, but acknowledged that some Black and Brown girls may not be afforded the same opportunities.

Her views still primarily endorsed standardization that placed the responsibility on the individual for their outcomes. Once Rita responded to Samira that the issues were systemic, she finally connected with that statement and compared it to the caste system in India. Samira may have struggled to understand the role of race in America, but discerned how class directly impacts one’s ability to succeed within her own culture. Samira reflected on the pressures to be smart and perform academically in the Asian community, and how difficult it is to meet that stereotypical standard of excellence. She also recounted how a cousin studied and worked hard to get admitted into a top institution in the United States, but because he lacked resources, her father had to purchase a computer for him to go to college. In Samira’s perspective, her cousin’s fate was based on his ability to work hard and his outcome was predicated upon his work ethic.

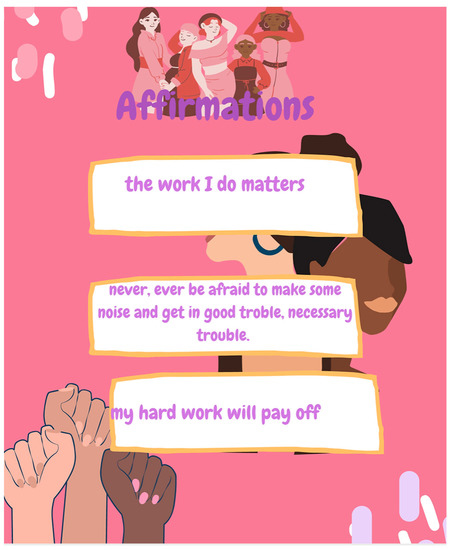

If we transition back to Brandy and Joy’s dialogue regarding the role of motivation, to what extent can one’s motivation contribute to or inhibit their success on standardized science assessments and in formal school? In Brandy’s reflection, see Figure 4, about the analysis of NAEP science scores across racial and gender lines, she originally stated “I think many people of color have no motivation to achieve greatness,” but then refined this thought based on Joy’s interactions with her to add “or don’t have the encouragement from others compared to most making the test scores lower for them.”

Figure 4.

Brandy’s reflection.

During the course of the summer, Brandy and Joy collaborated to create a series of motivational posters aimed at promoting positive affirmations for Black girls, with the explicit goal of instilling a sense of self-belief and confidence amongst girls who are interested in pursuing STEM-related fields. The impetus for this initiative stemmed from the shared realization that Black girls may benefit from encouragement as they navigate systemic barriers and challenges that can hinder progress toward their goals. By creating positive affirmation posters, Brandy and Joy sought to inspire girls, with the aim of promoting their participation in STEM. They hoped to motivate Black girls to pursue their interests and passions in STEM, while reminding them that they belong and have a community. The title of this paper comes from the first line in the affirmation poster in Figure 5—“The work I do matters.” They remind girls of the need to get in good trouble because the hard work will pay off.

Figure 5.

Positive affirmation poster created by Brandy and Joy.

10. Discussion

The findings revealed the importance of cultivating trusting and intentional learning spaces for Black and Brown girls to engage in open dialogue and critique oppressive discourses, and how adolescent girls can engage in difficult conversations by leaning into pluralism. They can realize the complexities of culture while promoting joy and social-emotional development. As we journeyed with Samira, Rita, Brandy, and Joy during a day of STEM camp, we learned the importance of creating spaces for children to engage in critical conversations, and to analyze and interpret data. There is an articulated vision in science education reform being able to capture students’ interests and provide them with the necessary foundational knowledge in the field [48]. It focuses on major practices, crosscutting concepts, and disciplinary core ideas that students should know. If done effectively, students should be able to critically consume scientific information related to their everyday lives, engage in public discussions on science-related issues, and become lifelong learners. The participants in this study were given an opportunity to be critical consumers of data about indicators used to measure the science proficiency of children their age. Based on their own identities, they grappled with what the average scale scores indicated and potential factors that could attribute to how girls across racial lines performed on the NAEP science assessment. Our research drew upon central tenets of CSP and the five core SEL competencies to promote adolescent development amongst Black and Brown girls [14,15]. Centering the girls and their experiences decentered the white gaze to create a counterspace where they could learn about themselves and others.

In sustaining their lives and revitalizing souls, we worked against spirit murdering that they are subjected to within formal schools [20]. Historically, Black children have been perceived as being biologically and culturally deficient and lacking biological traits to be successful in the school system [49,50]. Another taken-for-granted truth is that the Standardized Aptitude Tests are objective and children of color do not have the same intellectual capacity as their white counterparts giving the perception that people of color are not working hard enough or pulling themselves up by the bootstraps in order to achieve the American Dream [51,52]. The ideology of the American Dream is a myth because meritocracy assumes that all individuals are given the same opportunities to succeed based on their merit [53]. The damaging effects of White supremacy and these master narratives have led many to believe that Black children are racially inferior. Sadly enough, many Children of Color have internalized these feelings of racial inferiority [52]. Black girls are regularly portrayed as inferior and a problem to society and schools [27]. Racial hierarchies have been maintained by ideologies of white supremacy and become evident in performance outcomes on national assessments. A defining feature of “inherent superiority” has been used to justify power and the “right to dominance” [54]. To revitalize their souls, and the souls of other Black and Brown girls, Brandy and Joy wrote affirmations. They displayed responsible decision making in moving beyond the conversation on the source of motivation to creating a solution to help with the problem—positive affirmations. The literature reveals that racial microaffirmations promote wellbeing for Students of Color and serve as protective factors against microaggressions [55].

In considering loving critique and critical reflexivity, participants challenged harmful master narratives through relationship building and constructive dialogue. They began to reject deficit ideologies about their communities and nurtured inclusive practices toward equity and justice. Loving critique requires self-awareness and self-management where the girls reflected on their own thoughts and emotions and then regulated them in a way where they could engage in difficult conversations. For example, Rita provided a loving critique of Samira, using her experiences, self-awareness, and storytelling to push back against discourse that reproduced oppression. This allowed Samira to open up about her own culture and familial experiences to connect with Rita, reflect, and then adjust her thinking. The conversation went from Rita providing lengthy explanations, to a shared dialogue where they drew upon their life’s experiences to make sense of why girls their age on a national level had certain outcomes in science. Through critical discourses, Samira and Brandy practiced self and social awareness and were open to learning from different perspectives. They eventually acknowledged systemic issues that were in place and how racism can impact opportunities that Black and Brown girls are afforded.

Schools are a microcosm of the larger society and make visible the fact that opportunity gaps exist. Therefore, classrooms are not neutral, acultural, or objective. Students bring their experiences, beliefs, and values with them every day. Culture is complex, locally situated, and evolves over time. Culturally sustaining lessons recognize and value the diverse cultural backgrounds and experiences of all students, including girls. There is no expectation for the girls to leave their knowledge, backgrounds, and experiences at the door. It becomes a critical part of instruction and sensemaking. In STEM education, this means going beyond the Western-centric canon and including the achievements, contributions, and even the plight of Women of Color. By incorporating diverse role models as instructors and culturally relevant examples, we can inspire and affirm girls’ identities and interests in STEM.

Inclusive and equitable STEM learning spaces also provide girls with opportunities to engage in collaborative learning and develop their leadership skills. By fostering a sense of community and belonging, we can help girls feel supported and valued as they explore STEM topics. This is particularly important for Girls of Color, who often face multiple layers of marginalization and may feel isolated in predominantly white and male learning environments. SED was at the forefront in planning the summer curriculum and provided a space to discuss issues of power and equity and promote criticality. It is crucial to deconstruct current systems and curricula, rebuilding them in a way that embraces the genius of both teachers and students [56]. In this reconstruction, it is essential to prioritize the pursuit of joy, creating an environment where students can experience upliftment and personal fulfillment [56]. Through facilitated group discussions, reflection activities, and writing exercises, girls were introduced to SED concepts and invited to share their experiences in a collaborative and supportive environment. They were able to experience a sense of belonging and joy!

Finally, we must put in the work to sustain, revitalize, and imagine societies that are pluralistic and just. All individuals should feel respected and know that they are a valued part of the community regardless of background or identity. If we are promoting science for all, then our structures and systems should ensure that everyone has equitable access to opportunities and resources. For girls who tend to have negative experiences with STEM in traditional STEM environments, such as schools, informal STEM learning can help alter their perceptions of what it means to be a girl in STEM, provide encouragement to pursue and persist in STEM careers, and help counter the disparities for Black girls in mathematics and science [36,37,57,58]. Social-emotional development, which encompasses skills such as self-awareness, empathy, and responsible decision making, has the potential to create supportive STEM learning spaces for girls. As they navigate through challenges, they can develop a strong sense of self and persevere through setbacks, ultimately boosting their confidence and motivation to persist in STEM.

11. Conclusions

This study contributed to the knowledge base on culturally sustaining pedagogy, STEM education, out-of-school learning, and Black girlhood. We put CSP tenets in conversation with SEL competencies to provide a humanizing and comprehensive lens to decenter the white gaze and create a STEM counterspace where Black and Brown girls could be heard and thrive. Historically, their voices have been silenced in classrooms and experiences misrepresented in the literature. They have been adultified by society and in schools, and oftentimes do not have opportunities to simply be girls. We invited you into this counterspace to hear their truths through dialogue and written reflections. Our decision to delve deeply into the implementation of one culturally sustaining SED lesson provided insights into how it was facilitated, the girls’ interactions, and explicit connections to larger cultural and systemic issues in education. The summer program evoked critical and intergenerational conversations amongst the girls and STEM educators. When a curriculum is designed with Black and Brown girls in mind, they exercise agency and act in solidarity to make good and necessary trouble. This study reveals the importance of leveraging the assets that students bring with them into various learning spaces. Their histories and multiplicative identities informed the instruction and the direction of the lessons. Typically, NAEP science assessment data are discussed amongst teacher educators, researchers, and stakeholders representing federal organizations. Most children are unaware that a national science report card exists providing average scores for children in 4th, 8th, and 12th grades. This study invited them into the conversation to discuss how the data were disaggregated and what it means in terms of science achievement for children who look like them. Creating safe spaces for girls to express their emotions and experiences is central to fostering social-emotional development. This includes open conversations about gender bias, stereotypes, and microaggressions that they may face in STEM learning environments. By building girls’ emotional intelligence and their ability to navigate difficult situations, maintain healthy relationships, and thrive in STEM fields. In conclusion, we close this paper by reiterating the quote that we shared in the opening—“Even when your voice shakes, speak up and show up in your most authentic way. Your voice matters in this world. When this world tries to discredit you, just link arms with your sisters and show them that Black girls do matter.” [1].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S.K., L.P.-T. and S.E.; methodology, N.S.K., L.P.-T. and S.E., software, L.P.-T. and S.E.; validation, N.S.K., L.P.-T. and S.E.; formal analysis, N.S.K., L.P.-T. and S.E.; investigation, N.S.K., L.P.-T. and S.E.; resources, N.S.K.; data curation, L.P.-T. and S.E.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S.K., L.P.-T. and S.E.; writing—review and editing, N.S.K., L.P.-T. and S.E.; visualization, L.P.-T.; supervision, N.S.K.; project administration, N.S.K.; funding acquisition, N.S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC were funded by the National Science Foundation Early CAREER Award # 1943285.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Georgia State University (IRB #: H20398 approved 13 February 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Parental permission and youth assent were obtained from all youth participants involved in the study. Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available, due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

L.P.-T. and S.E. declare no conflict of interest. N.S.K. is the founder and executive director of I AM STEM, LLC., which provided the curriculum and professional development for the I AM STEM summer camp.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Code book.

Table A1.

Code book.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Loving critique (CSP) | Pushing back or calling out when discourse perpetuated dominant narratives/stock stories. |

| Critical reflexivity (CSP) | Self-reflection following loving critique. Awareness of self. Collapsed with the code “self-awareness.” |

| Self-awareness (SED) | See above. Understanding of self, sociohistorical context of self. |

| Sustaining lives and reviving souls (CSP) | Creating a space safe, encouraging, and showing care. Everything that spirit murdering is not. |

| Pluralism (CSP) | Decentering the white gaze and elevating counterstories. |

| Self-management (SED) | Regulating emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. |

| Responsible decision making (SED) | Making good choices while considering personal goals and moral and ethical standards. |

| Relationship skills (SED) | Building and maintaining positive and supportive relationships. |

| Social awareness (SED) | Showing empathy and valuing different perspectives. |

| Inequity | Awareness of sociohistorical context, realities of marginalized communities, and systemic oppression. |

| Reproducing/internalized oppression | Discourse that perpetuates deficit thinking and the status quo in schools and society. |

| Resisting Power | Refusing to comply or accept oppressive systems and being willing to challenge control. |

References

- Francois-Madden, M. The State of Black Girls: A Guide for Creating Safe Spaces for Black Girls; Marline Francois-Madden, LCSW: Middletown, DE, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.N. Black Girlhood Celebration: Toward a Hip-Hop Feminist Pedagogy; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2009; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Winters, V.E.; Esposito, J. Other People’s Daughters: Critical Race Feminism and Black Girls’ Education. Educ. Found. 2010, 24, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.W. Protecting Black Girls. Educ. Leadersh. 2016, 74, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Vining-Brown, S. Minority Women in Science and Engineering Education (Final Report); Educational Testing Service: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- King, N.S.; Pringle, R.M. Black girls speak STEM: Counterstories of informal and formal learning experiences. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2019, 56, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S. Swimming against the Tide: African American Girls and Science Education; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- King, N.S.; Pringle, R.M. Heaven Help us!: Insights into the marginalization of Black girls’ giftedness. In Understanding the Intersections of Race, Gender, and Gifted Education: An Anthology by and about Talented Black Girls and Women in STEM; Joseph, N.M., Ed.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B.N. “See me, see us”: Understanding the intersections and continued marginalization of adolescent gifted black girls in US classrooms. Gift. Child Today 2020, 43, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickhouse, N.W.; Potter, J.T. Young women’s scientific identity formation in an urban context. J. Res. Sci. Teach. Off. J. Natl. Assoc. Res. Sci. Teach. 2001, 38, 965–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. Diversity and STEM: Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities; National Science Foundation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Malcom, S.M.; Hall, P.Q.; Brown, J.W. The double bind: The price of being a minority woman in science. In Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science Minority Women Scientists Conference; AAAS Publication: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Malcom, L.; Malcom, S. The double bind: The next generation. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2011, 81, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, D.; Alim, H.S. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). What Is the Casel Framework? CASEL: Wheatley Hall, AR, USA, 2023; Available online: https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-is-the-casel-framework/ (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Nasir, N.S.; Lee, C.D.; Pea, R.; de Royston, M.M. Handbook of the Cultural Foundations of Learning; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Peristeris, K. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World. J. Teach. Learn. 2017, 11, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Three Decades of Culturally Relevant, Responsive, & Sustaining Pedagogy: What Lies Ahead? Educ. Forum 2021, 85, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.P. Pray You Catch Me: A Critical Feminist and Ethnographic Study of Love as Pedagogy and Politics for Social Justice; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Love, B.L. We Want to Do More than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alim, H.S.; Paris, D.; Wong, C.P. Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A critical framework for centering communities. In Handbook of the Cultural Foundations of Learning; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Malti, T.; Noam, G.G. Social-emotional development: From theory to practice. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 13, 652–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Positive Action, Inc. The Five Social Emotional Learning (SEL) Core Competencies; Positive Action, Inc.: Twin Falls, ID, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.positiveaction.net/blog/sel-competencies (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Jones, S.M.; Doolittle, E.J. Social and Emotional Learning: Introducing the Issue. Future Child. 2017, 27, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, K.M.; Tolan, P. Social and Emotional Learning in Adolescence: Testing the CASEL Model in a Normative Sample. J. Early Adolesc. 2018, 38, 1170–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solorzano, D.; Ceja, M.; Yosso, T. Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: The experiences of African American college students. J. Negro Educ. 2000, 69, 60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K.W.; Ocen, P.; Nanda, J. Black girls matter: Pushed out, overpoliced and underprotected. In Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies and African American Policy Forum; Columbia Law School: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nyachae, T.M.; Ohito, E.O. No disrespect: A womanist critique of respectability discourses in extracurricular programming for Black girls. Urban Educ. 2023, 58, 743–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamma, S.A.; Anyon, Y.; Joseph, N.M.; Farrar, J.; Greer, E.; Downing, B.; Simmons, J. Black Girls and School Discipline: The Complexities of Being Overrepresented and Understudied. Urban Educ. 2019, 54, 211–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.A. Approaches to multicultural curriculum reform. Multicult. Educ. Issues Perspect. 2007, 6, 247–266. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Identifying and Supporting Productive STEM Programs in Out-of-School Settings; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dierking, L.D.; Falk, J.H.; Rennie, L.; Anderson, D.; Ellenbogen, K. Policy statement of the “informal science education” ad hoc committee. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2003, 40, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, L.J. Learning science outside of school. In Handbook of Research on Science Education; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007; pp. 125–167. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein, N.W.; Meshoulam, D. Science for what public? Addressing equity American science museums and science centers. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2014, 51, 368–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.S. Opening doors with informal science: Exposure and access for our underserved students. Sci. Educ. 1997, 81, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, T.B.; Id-Deen, L. Nurturing the Capital Within: A Qualitative Investigation of Black Women and Girls in STEM Summer Programs. Urban Educ. 2023, 58, 1298–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, C.; Smith-Mutegi, D. Making “it” matter: Developing African-American girls and young women’s mathematics and science identities through informal STEM learning. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2022, 17, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N.S. Black girls matter: A critical analysis of educational spaces and call for community-based programs. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2022, 17, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedinger, K.; Taylor, A. “I Could See Myself as a Scientist”: The Potential of Out-of-School Time Programs to Influence Girls’ Identities in Science. Afterschool Matters 2016, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Brackett, M.A.; Elbertson, N.A.; Simmons, D.N.; Stern, R.S. Implementing Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) in Classrooms and Schools; National Professional Resources, Inc.: Lake Worth, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, N.M.; Hailu, M.F.; Matthews, J.S. Normalizing Black girls’ humanity in mathematics classrooms. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2019, 89, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodak, R.; Meyer, M. Critical discourse analysis: History, agenda, theory and methodology. Methods Crit. Discourse Anal. 2009, 2, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.; Malancharuvil-Berkes, E.; Mosley, M.; Hui, D.; Joseph, G.O.G. Critical discourse analysis in education: A review of the literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2005, 75, 365–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, T.A. Critical discourse analysis. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis, 2nd ed.; Tannen, D., Hamilton, H.E., Schiffrin, D., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 466–485. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, T.A. Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse Soc. 1993, 4, 249–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullet, D.R. A general critical discourse analysis framework for educational research. J. Adv. Acad. 2018, 29, 116–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, T.A. Aims of critical discourse analysis. Jpn. Discourse 1995, 1, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. A Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu, J.U. Minority education and caste: The American system in cross-cultural perspective. Crisis 1978, 86, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, P.L.; Welner, K.G. Achievement gaps arise from opportunity gaps. In Closing the Opportunity Gap: What America Must Do to Give Every Child an Even Chance; Carter, P.L., Welner, K.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein, R.J.; Murray, C. The Bell Curve: The Reshaping of American Life by Differences in Intelligence; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Sensoy, Ö.; DiAngelo, R. Is Everyone Really Equal? An Introduction to Key Concepts in Social Justice Education; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McNamee, S.J.; Miller, R.K. The Meritocracy Myth; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lorde, A. Age, race, class and sex: Women redefining difference. In Knowing Women: Feminism and Knowledge; Crowley, H., Himmelweit, S., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1992; p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, L.P.; Gonzalez, T.; Robles, G.; Solórzano, D.G. Racial microaffirmations as a response to racial microaggressions: Exploring risk and protective factors. New Ideas Psychol. 2021, 63, 100880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]