1. Introduction

Societal evolutions over the past few decades affect the curriculum and the way education and assessment are shaped [

1]. Both internationally and nationally, a trend toward a culture of measurability can be observed [

2,

3]. Discussions about the (declining) quality of education and policy decisions in this context rely on studies such as PISA, PIRLS and TIMMS [

4,

5]. The responsibility of school leaders for student learning outcomes [

6] as well as institutional pressures is increasing [

7,

8]. Consistent with this, school leadership is a policy focus with an increasing attention to school leader professionalization too [

9].

Bush and Glover [

10] define school leadership as “a process of influence leading to the achievement of desired goals. Successful leaders develop a vision for their school based on their personal and professional values. They articulate this vision at every opportunity and influence their staff and other stakeholders to share the vision. The school’s philosophy, structures and activities are geared towards achieving this shared vision” (p. 8).

A first dimension is linked to vision development and influencing and facilitating processes that lead to the achievement of core educational goals, namely quality teaching by teachers [

11,

12] and of pupils linked to this teaching [

13,

14]. The second dimension emphasizes the school leader’s task of uniting the team around core values and related strong teaching and learning practice bases [

15,

16]. A third dimension is propagating this vision [

11].

Since the 1980s, much research has been dedicated to the effects of educational leadership. Even though real effects of educational leadership on student achievement prove difficult to measure [

17,

18] and cannot be unequivocally demonstrated, there is widespread recognition of the importance of school leadership on high-quality education [

19,

20]. It is therefore essential that professionalization initiatives (PI) for school leaders address aspects of effective leadership [

13], both with regard to educational leadership and the many other tasks and responsibilities of the school leader [

21], and that these initiatives are also sufficiently adequate [

22,

23]. Many countries developed competence profiles for selection and evaluation and as a basis for determining the program of PI for school leaders [

22].

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Concrete Organization of the Professionalization Course

The literature review shows that several factors can facilitate the influence of PI on learning outcomes among school leaders. These factors are situated both on the goals and content, the organization and the approach. Empirical research on the real (long-term) effects of PI and on underlying explanatory processes is limited [

22]. There is also little research on the functioning and added value of more complex and long-term PI [

54]. As a result, it is unclear how these different factors specifically influence learning, how this influence may depend on characteristics specific to the school leader or their school context, how these factors reinforce or weaken each other, how the deployment of these different factors is optimally spread within a long-term trajectory and with which iteration. Moreover, few in-depth and large-scale studies are available, with an interaction between quantitative (as a basis for generic statements) and qualitative (as a basis for explaining these statements in depth) data.

This problem statement forms the basis for this study, in which we chose to design a long-term professionalization course (2 years) and implement it as the research setting in which a number of characteristics of powerful professionalization [

54,

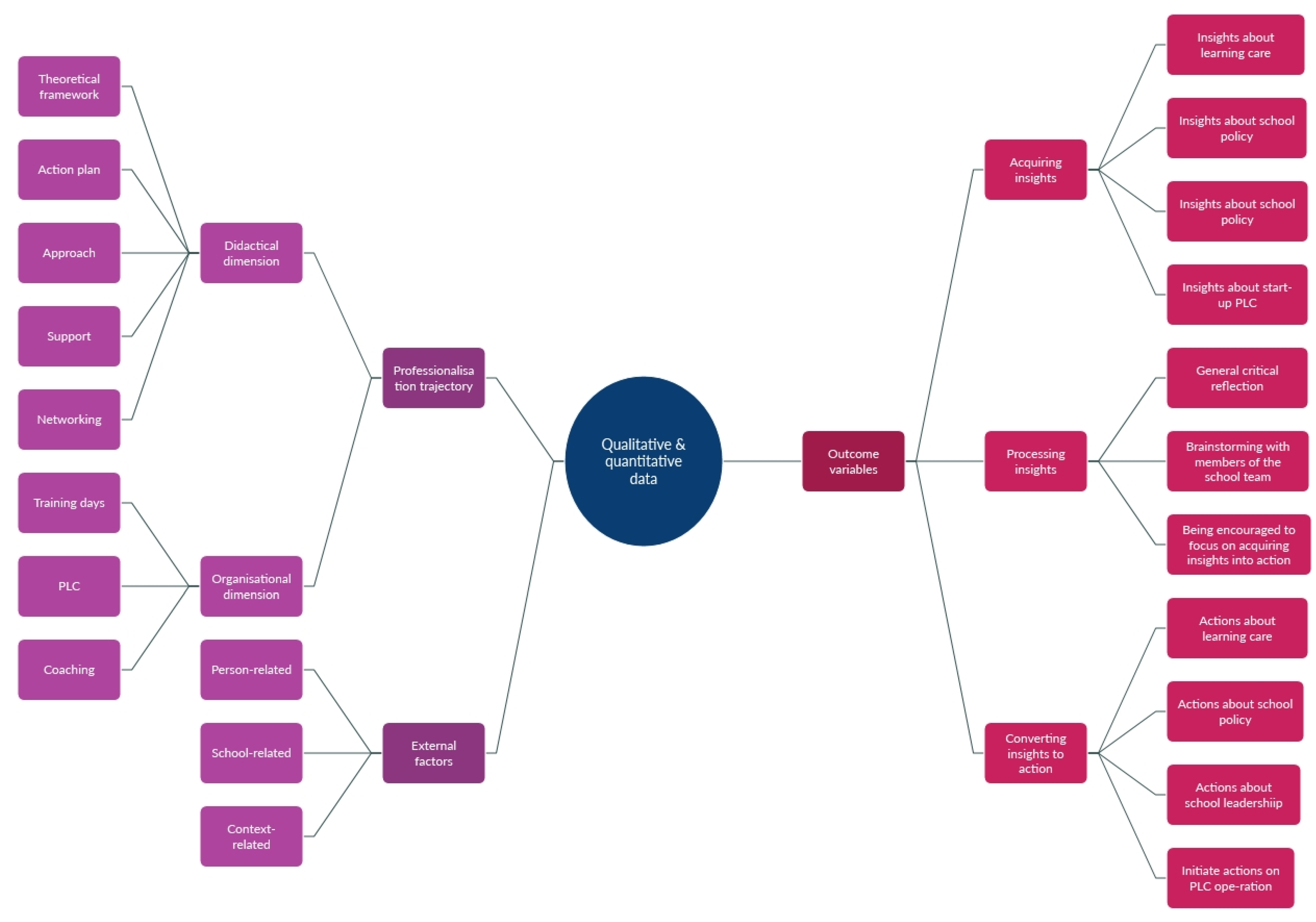

55] were implemented. This makes it possible to examine the impact of organizational and didactical factors as well as their mutual interaction on certain outcome variables (see

Figure 1).

Given that the didactic dimension runs as a thread through the organizational dimension, the hypothesis was that responding to an interaction between the two leads to an increased influence of the PT on perceived outcomes. Which specific interaction contributes most to this was also the subject of research.

The outcome variables of the PT were ordered according to the levels of depth of learning by Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick [

24]. Specifically, this means that the outcome variables were arranged thematically according to the three highest levels:

level 2: acquired insights regarding learning support, school policy, school leadership and starting PLC;

level 3: processing acquired insights through reflection in general, being stimulated to brainstorm with members of the school team and being stimulated to be goal-oriented in terms of the approach at school;

level 4: converting acquired insights into action plans and concrete actions regarding the vision on learning support, school leadership and starting PLC.

In this research, we examined the outcomes on the fourth level with a focus on converting acquired insights into action plans and concrete actions, which is less examined in other research. However, we hypothesized that this depth of learning with goal-oriented and sustainable actions is not possible without reaching the preceding levels, also consistent with the context and needs of the participating school leaders and their school.

3.2. Research Model and Questions

We wanted to examine the influence of applying characteristics of effective professionalization in PT for school leaders in terms of the dimensions (1) organization and (2) didactics of the PT, as well as their mutual interaction and the interaction with possible mediating external factors on the fourth level of learning outcomes. All this leads to the following research model (

Figure 1).

The central research questions were the following:

Q1: What is the perceived added value of participating in the PT in terms of taking actions on school development (level 4)?

Q2: Which factors of effective professionalization on the dimensions of organization and didactics influence the perceived outcomes of a PT (level 4)?

Q3: Which interplay between factors of effective professionalization influence the perceived outcomes (level 4) of the PT and the transition to the own school, and for what reason?

Q4: Which non-PT factors (medially) influence perceived outcomes (level 4) of the PT?

3.3. Research Context and Participants

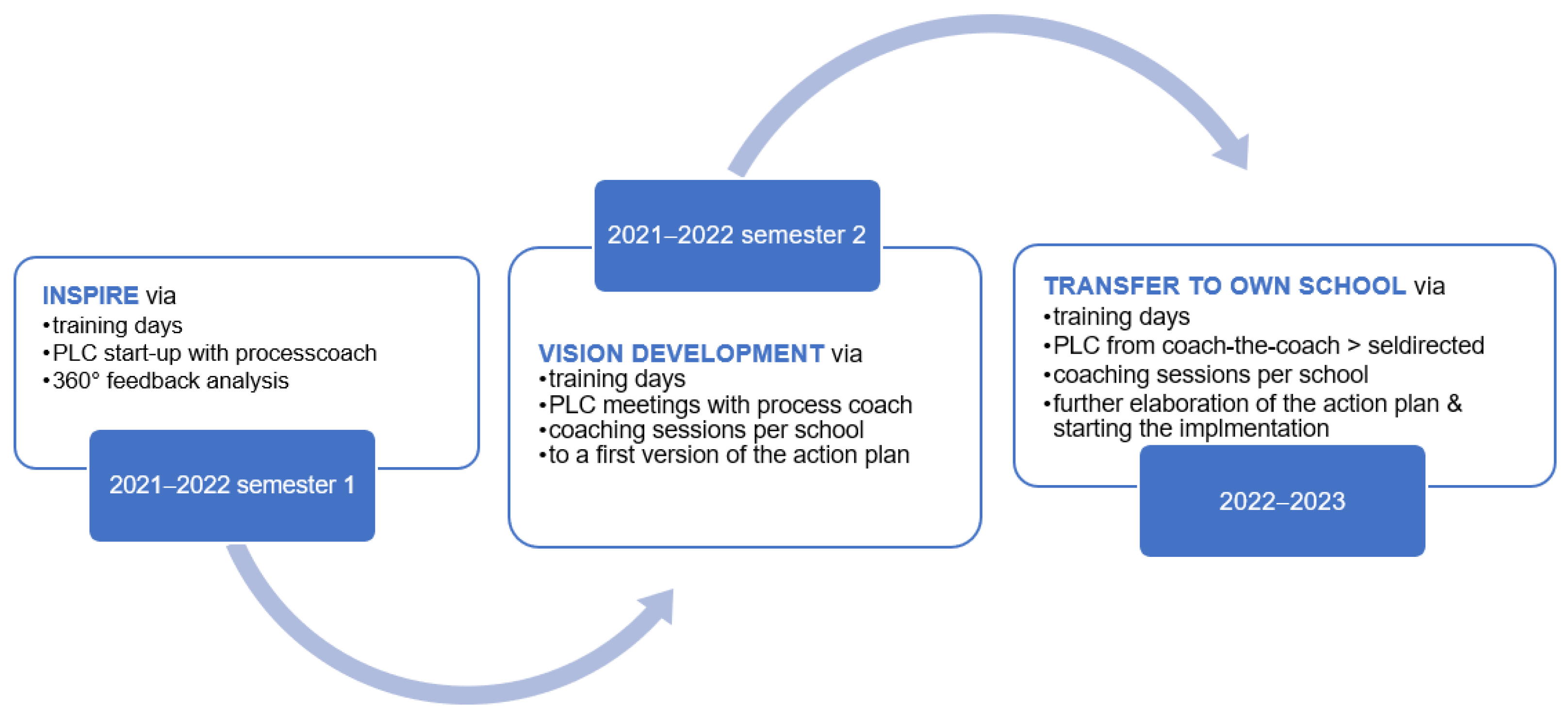

For the period 2021–2023, the PT, commissioned by the Flemish government (Belgium) consisted of training days, PLC meetings and coaching (

Figure 2). During each of the five training days of year one, a different content focus was central [

56]. Hereby, the organizers foresaw a clear link to the principles of ‘leadership for learning’ [

57], as further transformed into the development model ‘Team School. Creating learning communities in education’ [

58].

During the training days for the full group of participants, the focus was on providing actual content aimed at acquiring insights and illustrated with practical examples. The further deepening and concretization of the acquired insights took place in the PLC of school leaders and internal support staff, composed per registered partnership. In the PLG, the focus was on learning from and with each other, with extra social stimulation provided by the smaller group. The PLC met four times in the first year. In addition, coaching was provided for each school and focused on their specific questions. During the first year, two coaching meetings were planned. Four additional training days were organized in May 2022, focusing on the concrete application of PLC process coaching. These days were optional for participants of the PT and other teams could also register, with the aim of facilitating the dissemination and broadening of the base on this topic.

During the 2021–2022 school year, 149 participants from primary education/K-12 (43%), or secondary education (57%), followed the PT. In total, 58% held a management position, 55% of them in secondary education. In total, 42% occupied a (coordinating) middle management position at school linked to learning support, 60% of them in secondary education (

Table 1).

To generate and facilitate shared school leadership, participants were encouraged to register two colleagues per school. A total of 93% of respondents participated together with a colleague. For primary school principals, this was not always possible given the small school teams.

Each partnership was organized as a PLC. The partnership with 19 schools was split into two separate PLC groups. Each PLC consisted of 7 to 15 participants and was supervised by a permanent process coach. Each process coach supervised a minimum of one and a maximum of three PLC.

The coaching sessions were supervised by the process coach of the respective PLC of the participating schools. Each school decided whether to participate (not) in the (both) sessions, whether only the school leader participated. A total of 53% (n = 129) participated in at least one coaching session.

3.4. Data Collection

The research questions were answered by adopting a mixed methods approach because combining quantitative and qualitative data with proportionate weight increases relevance and provides an opportunity to check the relationship between variables.

Prior to the start of the PT, participants completed a written initial situation analysis (ISA) with closed- and open-ended questions. After finishing the first school year in May 2022, a written survey with closed- and open-ended questions was organized, aimed at questioning experiences with the PT and perceived outcomes. These surveys were developed based on literature research and observations during the trajectory. In total, 131 out of 149 participants (88%) completed the final survey. In total, 83% (n = 123) of the participants completed both the ISA and the final survey. Everyone who completed the written survey participated in the training days and PLC meetings. To calculate the impact of the coaching sessions (n = 66), only quantitative data from those who participated were used.

In June 2022, focus group discussions were organized with PLC groups and in-depth interviews with school leaders (

Figure 3) to collect further explanatory qualitative data for the quantitative data and to further question trends in the quantitative data already collected. Participants were invited to participate during the last training day and PLC meeting, and via email. The semi-structured online interviews were conducted using a question protocol drawn up on the basis of the literature review and observations. Focus group interviews lasted up to 90 min and in-depth interviews up to 60 min in June and early July 2022 and were recorded with the knowledge and consent of all participants. Of the 15 PLC, 11 participated in a focus group discussion. A total of 40 school leaders (=53%) distributed across the different PLC groups participated in an in-depth interview.

3.5. Data Processing and Analysis

Exploratory factor analyses (using principal axis factoring) were conducted on the quantitative data, processed in SPSS, to arrive at meaningful, distinguishable and reliable scales. Eight factors were constructed (

Table A1 and

Table A2). Cronbach’s alpha as a measure of reliability was above 0.7 for all scales.

Six-point Likert scales were used (completely disagree—disagree—rather disagree—rather agree—agree—completely agree). To create meaningful descriptors of the data, these scales were made numeric (completely disagree (1)—etc.—completely agree (6)). Thereafter, all Likert scales were standardized to enable analyses.

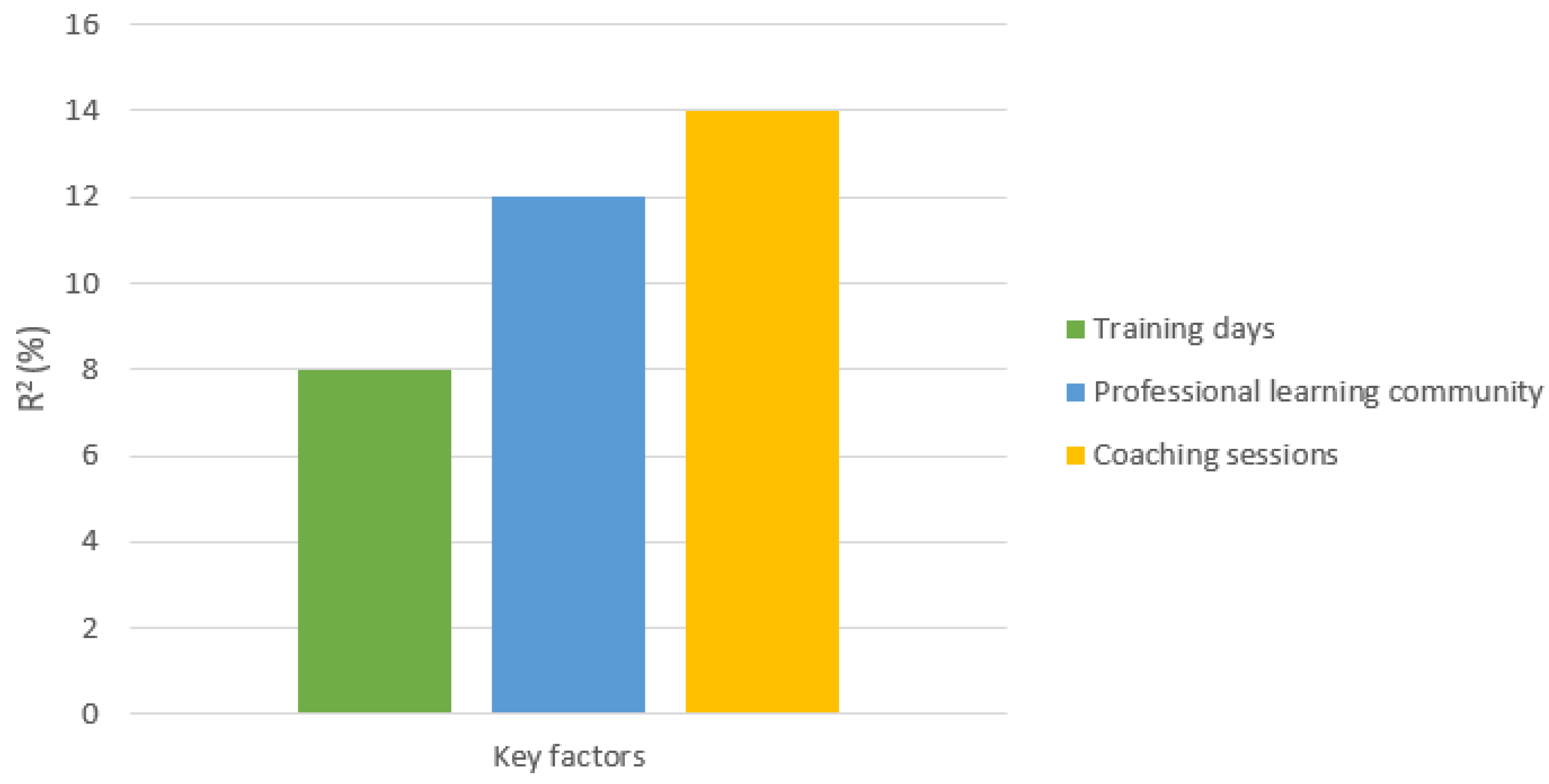

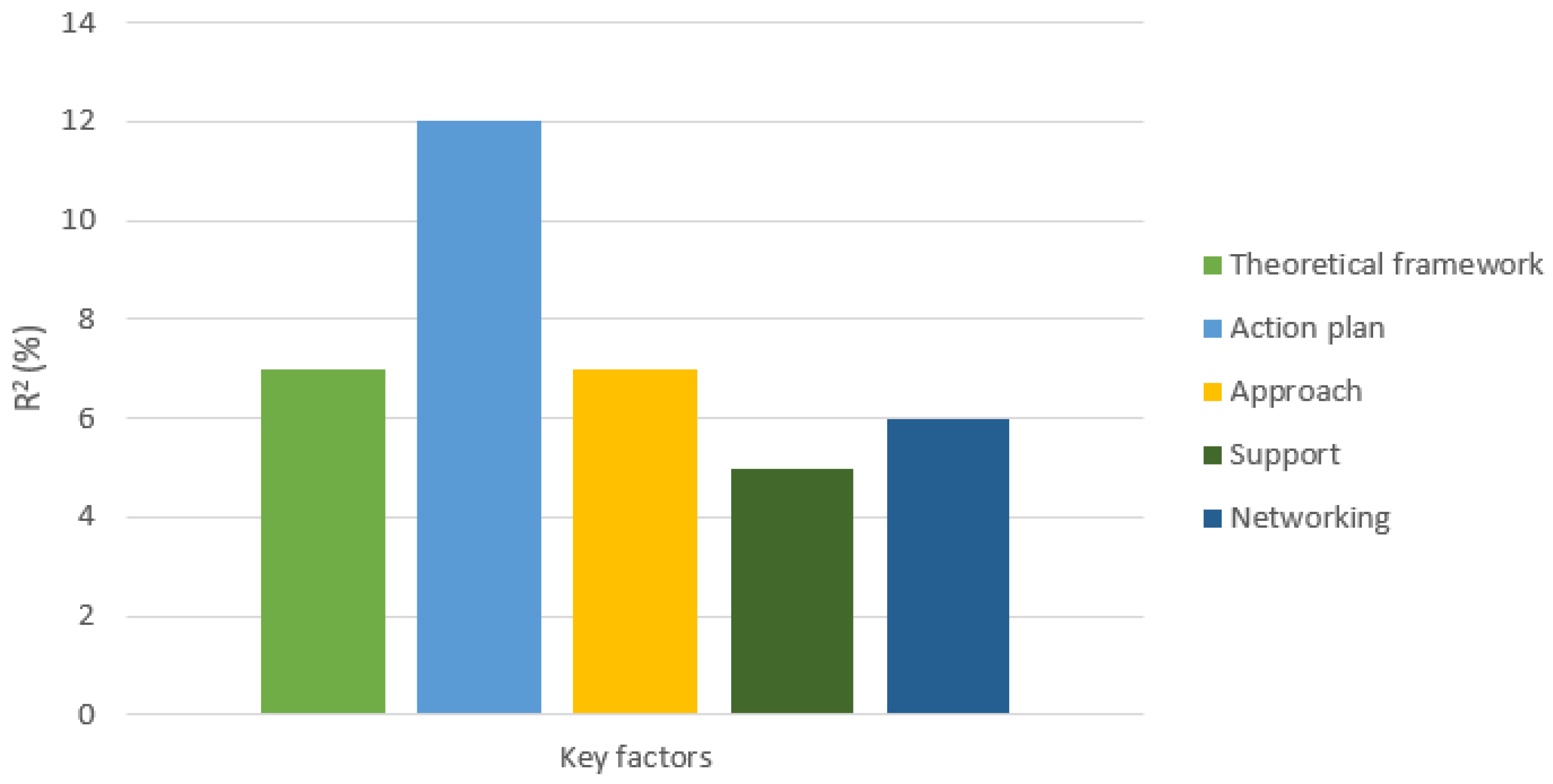

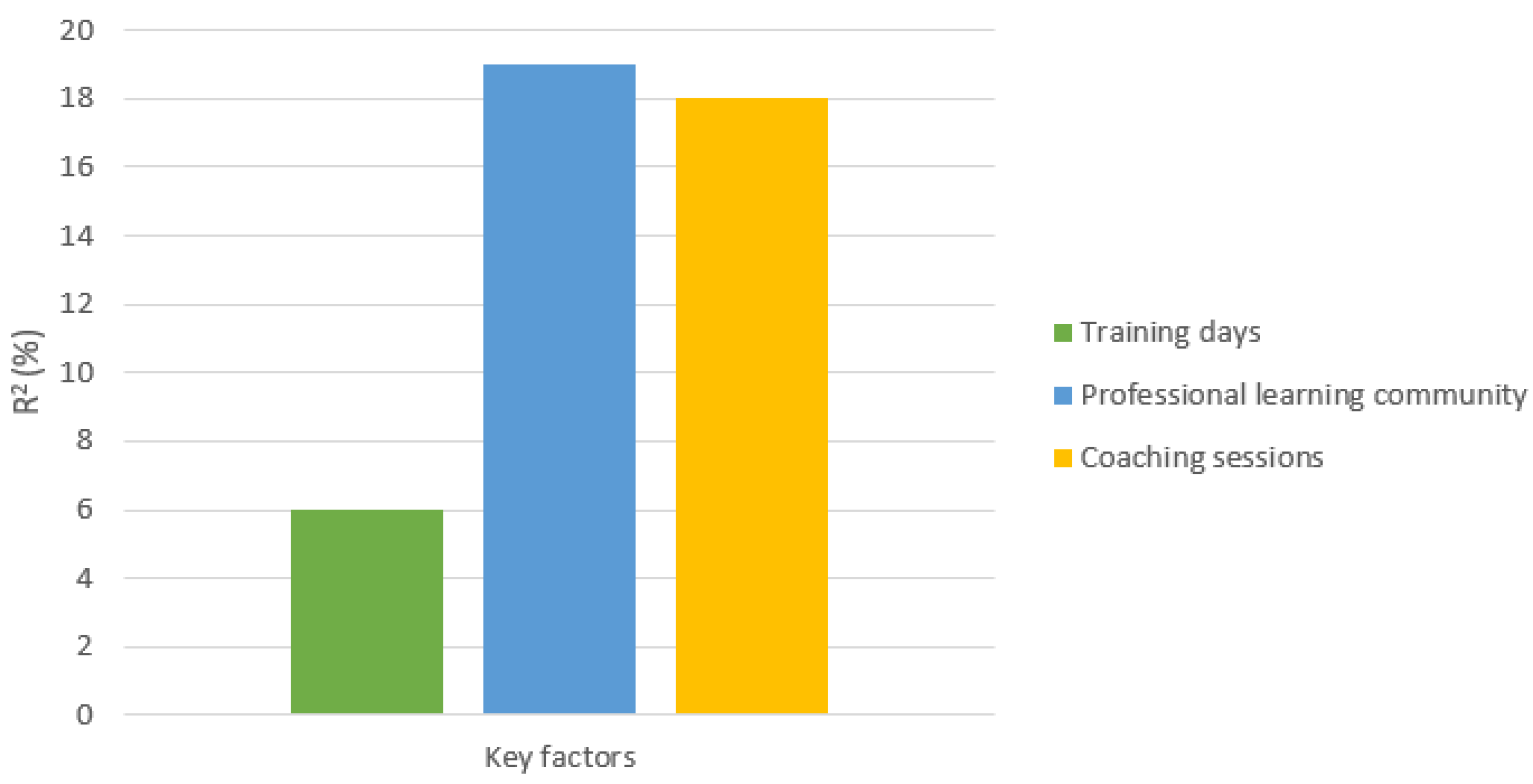

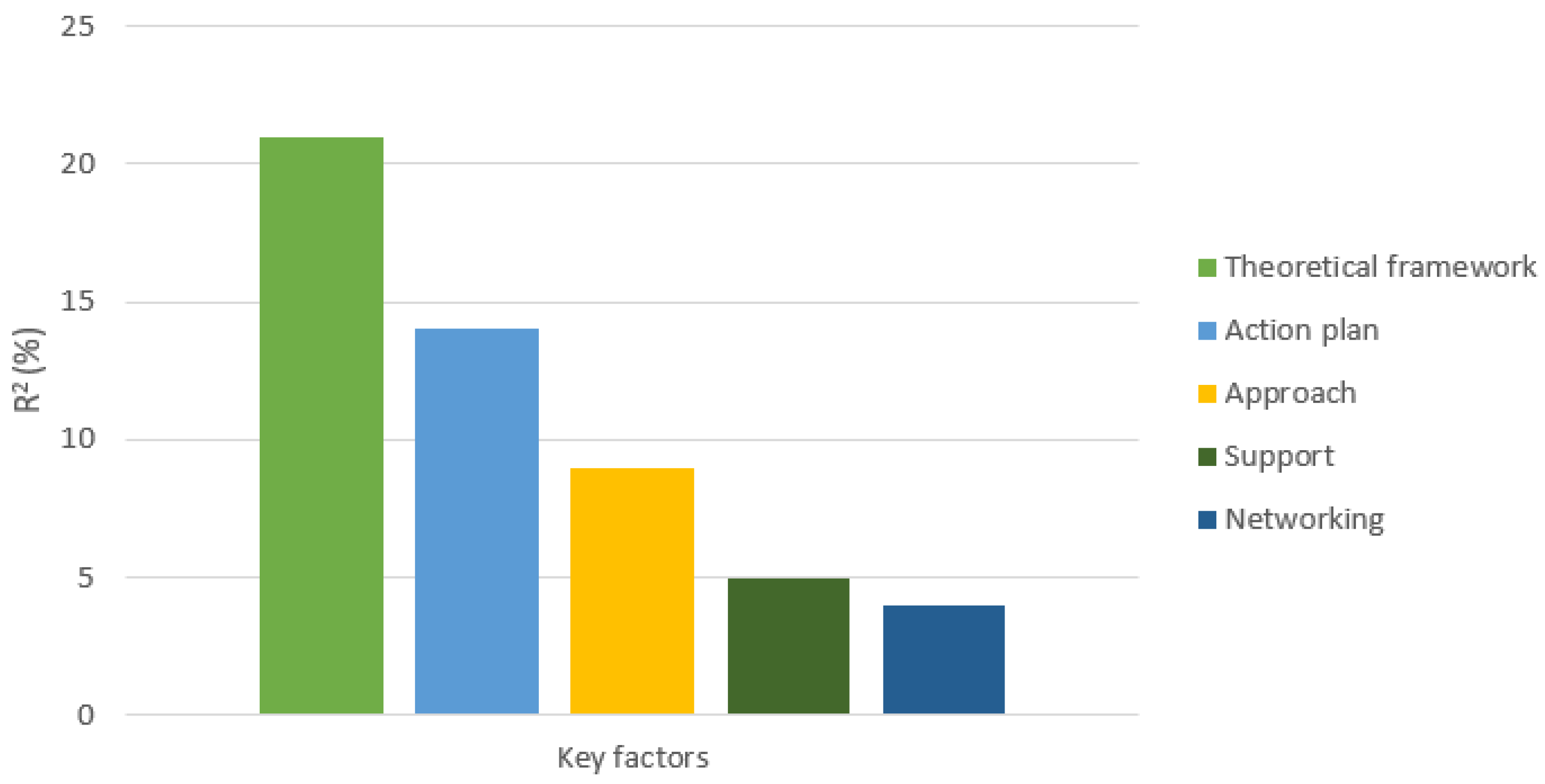

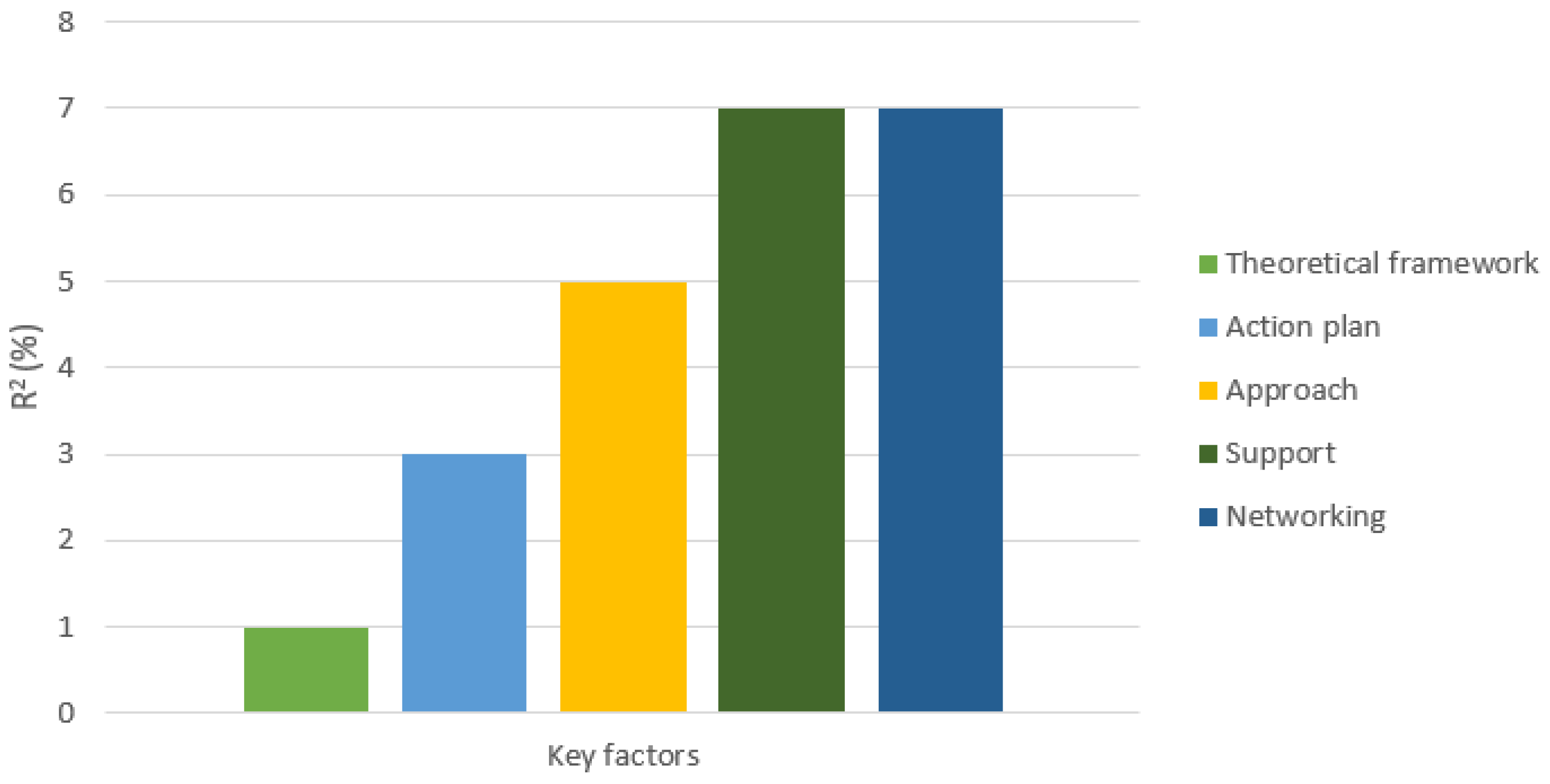

The strength of the perceived relationship between the eight factors of effective professionalization and the outcome variables was examined through a single regression analysis (SRA) and multiple regression analysis (MRA). All assumptions of the regression analysis were met in each case. A statistical approach based on a stepwise linear regression analysis (SLRA) was used for each outcome variable to determine the factor(s) with the greatest statistical predictive value. For naming the extent to which the variance in the dependent variables is explained by the explanatory independent variables (R²), the following division was used: <10% weak, 10–25% moderately strong, 25–50% strong, 50% very strong and 100% perfect relationship.

The qualitative data were supplemented with and underscored by (quantified) qualitative data and quotes from open-ended questions of the written survey (S), the focus group discussions (F) and the in-depth interviews (D). The qualitative data were processed in NVIVO and organized in line with the research questions, with an initial subdivision consisting of the PT, external factors and outcome variables (

Figure A1).

5. Discussion

The central research question was to what extent organizational and didactic features of a PT for school leaders as well as their mutual interaction encourage concrete learning-driven actions on school development, and what are decisive elements in this, respectively. This is an innovative research focus because it examines how school leaders not only acquire insights and have the intention to implement change but are effectively encouraged to prepare and take action [

60]. In order to prepare action plans and take concrete actions that are sustainable and tailored to the school, the underlying processes of acquiring insights and processing these insights (together with the team) are equally important to achieve depth.

It became clear that reaching the level 2 (acquiring) insights and 3 (processing acquired insights through reflection) of the Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick model [

24], which was generally the case in this PT, is necessary for reaching level 4 (converting insights into action), but in itself is not sufficient. For instance, creating (and coaching) goal orientation and focused application on school practice is further needed. The other way around, reaching level 4 will also deepen knowledge (level 2) and reflection (level 3).

Participants described the structure of the PT as balanced with a logical cyclical progress and composition over a period of time [

42,

43]. For them, the training days represented a valid starting point for processing and transforming the theoretical frameworks and content into the school context, supplemented with concrete examples, in connection with the PLC and coaching, at least for those who participated, where the preparation for one’s own priorities is further and even more question-oriented analyzed. Preparing an action plan and using a varied and activating approach with focus on peer learning [

19] during formal and informal moments [

53] encourages reflection [

42]. It also provides structure and rhythm to the transfer into school-specific goals. The PT is distinguished by its structure from common trajectories with usually only training days, PLC or coaching, where either theoretical frameworks or the transfer to one’s own school context are missing. According to the participants, that interaction just increases learning efficiency and facilitates really concrete changes in one’s own school [

25]. Participants experience the active support of this conversion into a school vision and action plan and the follow up of plans made by the experienced lecturers and their own process coach [

19,

29] as contributing to the goal and action orientation of their approach and as useful pressure to actually take action.

Participants also mentioned the important role of process coaches during the PT and the positive effect and added value they experienced [

53]. Quality implementation of process coaching is important both in facilitating and supporting (through feedback) school development processes and in establishing links between the content and approach of the training days, PLC and coaching sessions. The process coach facilitates the depth of learning processes through a theoretical growth-oriented framework [

51,

55] and by making things explicit [

52]. However, a more negative experience with the process coach causes participants to participate little or not at all in the coaching sessions and to perceive the PLC as more superficial and less fruitful. Participants also found the interaction between the three organizational forms of the PT more unclear.

Given the crucial importance of their position and a quality fulfilment of it in combination with a high responsibility [

6] and pressure [

7,

8], school leaders wished that (long-term) professionalization for their profession is free of charge [

38], which also implies a form of appreciation [

61]. Participants pointed out the importance of being concretely stimulated to take concrete actions on school development [

43]: they appreciated the fact that a PT is not non-committal, a dimension only sporadically demonstrated by other research [

24,

44]. According to participants, the logistical and organizational support, follow-up and communication also adds to the positive perception about the PT. The time provided during the PT for concrete application was appreciated by participants, which is in line with research [

53]. Nevertheless, the structural lack of professionalization time within the job remains one of the factors that school leaders perceive as negative because taking time outside the PT to thoroughly reflect and implement policy in collaboration with the team often gets snowed under by ‘the delusion of the day’ and emergency solutions to guarantee the school’s basic role [

41,

46]. Participants indicated that this resulted in them achieving fewer predefined actions than desired.

When analyzing the quantitative and qualitative data using existing guidelines [

21,

23], the PT for school leaders appears to largely meet these criteria. An influence of mediated variables on outcomes is possible [

37]. Based on the results, we can state that participation in a PT for school leaders can transcend the initial situation, while contextual situations can conquer during participation in the PT and create additional challenges in terms of prioritization [

29,

43,

48]. On a team-oriented level, the growth-oriented mindset of the entire team during participation proves to be especially decisive for support, a shared framework and language, shared leadership and the transfer into concrete actions in one’s own school. Participating together with a colleague increases the perceived support and concrete transfer to one’s own school context [

49]. In such a positive learning climate, school leaders experience more support, which supports them for further engagement [

46,

47,

62].

6. Conclusions

This research offers a relevant and unique perspective on how professionalization trajectories for school leaders have a real impact on concrete actions in one’s own school. Through mixed methods research, this study outlined an innovative view on factors perceived by participants as working for effective PT for school leaders. This research will contribute to the evaluation and optimalization of current and future PT for school leaders and the targeted selection of valuable PT to be involved in [

24]. This also leads to concrete recommendations for practice and further research.

6.1. Recommendations for Practice

Firstly, it is important that school teams have structural space for collaborative work and professionalization. Only in this way do planned actions on school policy lead to commitment by the whole team and sustainable implementation. Both the school leaders and government should facilitate this structural professional development time. It is also necessary that professionalization makes a structural part of the school leaders’ job. Implementation of PT happens the best by directly linking this to concrete and goal-oriented school development in one’s own school. The government should support long-term professionalization initiatives in which several team members per school can participate, precisely to increase a shared language and focus, and shared leadership.

Secondly, the government should support powerful professionalization initiatives organized by different education-oriented partners, with opportunities to encourage relevant and practice-oriented school development. In doing so, it is important to ensure a thoughtful combination of and interaction between training days with a focus on theoretical frameworks and practical examples, encouraging reflection (including from 360° feedback), a first exchange with peers and inspiration in the function of the own school context, with (as a common thread) the elaboration of a concrete policy/action plan; meetings of professional learning communities with the partnership to convert the frameworks and inspiration provided into the school context and to discuss school-specific priorities/learning questions critically and constructively with peers; support using process coaching, with the aim of further concretizing the school policy and/or action plan; and individual coaching per school to further support the conversion of inspiration, insights and a growing action plan into school-specific implementations and to respond to individual leadership questions. This organizational dimension is best combined with facilitating networking opportunities. In this way, PT can best take advantage of opportunities that arise within school partnerships to stimulate peer learning and peer feedback.

6.2. Recommendations for Further Research

At the time of the data collection, the PT was still ongoing. In addition to the learning outcomes examined after 1 year of training, it is relevant to examine how school leaders perceive further sustainability, as well as how further progress and integration can be facilitated, given that embedding learning outcomes takes time [

23,

43] and is best tailored to each school. How school leaders further implement and use the action plan based on the initial PT is interesting to investigate.

Further research on the approach of the process coach that school leaders experience as facilitating is relevant because this research already indicated that process coaching has an impact on the perceived quality of professionalization trajectories [

53]. Because learning is both an individual and social activity, it is interesting to explore what relationship school leaders find valuable within a PT. Starting from existing partnerships is a strength for jointly undertaking a growth process in terms of school development. At the same time, it can be a brake if school leaders are less motivated, or the focus of the PT and the PLC they participate in does not match their needs. Mapping the factors that may (or may not) be facilitating will provide insight into criteria for sustaining the effects of a PT for school leaders or standalone PLC of existing partnerships. Finally, this study focused on the learning outcomes of school leaders, while the research literature shows that there may be secondary outcomes associated, such as professional well-being, isolation and the network [

25], with an effect on school development. This is an important goal for further research.