Abstract

High-quality principal internships are defined, in part, by support from high-quality principal mentors. We traced the development and quality of principal mentor–intern relationships during an academic school year and found that mentors played a significant role in determining the extent to which interns were isolated or integrated into the school leadership team. Specifically, mentors influenced (1) the types of tasks and activities interns were allowed to engage in, (2) the level of autonomy interns were afforded, and (3) the support interns received. Importantly, interns’ own proactivity shaped each of these aspects of their internship experience.

1. Introduction

Decades of research supports the finding that principals are one of the most important factors in determining the culture, climate, and performance of schools [1,2]. Among the many roles that principals perform, one that has received too little attention in the research literature is the role principals play as mentors of future school leaders. In fact, research on principal preparation suggests that the internship is the most important component of principal preparation [3,4,5], and high-quality internships are, at least in part, defined by support from expert principal mentors [6,7,8]. Furthermore, research on principal mentors finds that they vary in many important ways, including their quality as role models, their understanding of the internship’s purpose and design, the types of activities and experiences they allow interns to engage in, and their ability to work with university supervisors [6,9,10,11].

The purpose of this study is to build upon this research by exploring the principal mentor–intern relationship of 22 full-time, job-embedded interns during the 2019–2020 school year. Specifically, we analyzed interns’ weekly reflections to trace the development and quality of their relationship with their principal mentor during their full-time internship. We ask: How do principal mentors influence interns’ leadership development throughout a full-time internship?

2. Perspective

Mentoring has long been considered an important part of many professional fields, particularly those with clinical practice such as medicine, journalism, the law, and education [12,13,14]. While mentoring can assume many different forms both inside and outside the classroom, it is “generally understood as a personal or professional relationship between two people—a knowing, experienced professional and a protégé or mentee—who commit to an advisory and nonevaluative relationship that often involves a long-term goal” [15] (p. 2). Though the traditional view of mentoring is shaped by transactional and technical processes—for instance, with mentors transmitting the necessary skills and abilities to mentees—recent work highlights the constructivist and democratic nature of alternative mentoring, where both mentor and mentee learn from and with each other [16].

Mentoring is an integral part of leadership preparation, as expert site-based principal mentors can help interns successfully navigate the difficult role transition from teacher to leader [9,17,18,19,20]. Given their critical role in leadership development, principal mentors must be carefully identified, recruited, and selected. Programs may choose to select mentors based on a track record of generating or progressing toward higher academic outcomes [21,22]. Research has found that the quality of the mentor varies based on the principals’ willingness to support the intern, their past experiences with mentoring, and their understanding of the internship purpose and design [23]. The success of the internship placement is, to a large extent, also contingent on the degree to which university programs and school districts can partner and collaborate [9,10].

Mentors should expose their mentees to as many facets of leadership as possible [19,21], so that interns can learn whether building level leadership is for them or not. These activities might include the supervision and evaluation of teachers, chairing planning committees, conducting in-service training, preparing reports, and communicating with parents and students [24]. Moreover, recent research emphasizes the need for mentors to prioritize instructional leadership opportunities [11,25]. Importantly, mentor principals who are not trained have been found to provide interns with a limited scope of leadership activities or delegate to interns non-instructional, managerial tasks such as student discipline or testing [10,26]. Virella and Cobb encouraged preparation programs to consider ways to enhance the alignment between coursework and internship experiences through training and clear checkpoints throughout the year with the onsite mentor [20].

Furthermore, the quality of the mentor–mentee relationship seems to be related to personal characteristics, such as mutual respect, honesty, trust, and openness; professional discourse, which includes sharing ideas, insights, and experiences in a reflective process; and time and frequency of communication [18,19,27,28]. Time, in particular, is an important element to consider, as mentees cite a lack of time for frequent contact with their mentor principals (e.g., monthly meetings), often due to the accountability pressures that principals face [23,29]. Establishing clear goals at the onset of the internship experience between mentor and mentee helps build trust, clarify priorities, and develop goal setting skills within the intern [11,20,30]. Clearly, the length and type of internship matters, as interns engaged in a year-long internship have more opportunities to develop a relationship with their mentor principal than interns looking only to fulfill a required number of contact hours [8].

Of course, it is not only mentees that benefit from mentoring relationships, as they often bring the latest research and evidence-based practice to the relationship [31]. For example, Clayton found that mentors with strong backgrounds in organizational management were challenged by interns with an orientation more contemporary understanding of leadership for student learning [10]. While these mentors’ reactions differed, she found that many were enthusiastic about learning more about interns’ projects and the current discussions in leadership preparation [10]. Thus, a productive mentor–mentee relationship can help both leaders to develop and grow in a reciprocal relationship [9,20,28,32].

In short, the literature demonstrates that mentorship can be a powerful lever in school leadership preparation. Principal preparation programs and school districts can work together to identify, assign, and support mentor–mentee relationships.

3. Active Learning

Active learning through full-time, year-long residencies provides aspiring leaders with the opportunity to experience the theoretical concepts learned within the classrooms of principal preparation programs [7,23]. “Research across fields has demonstrated that contextually relevant, real-world learning opportunities that foster self-reflection are most likely to lead to valuable adult learning outcomes” [7] (p. 291). Reflective learning, coupled with supportive mentorship by practicing expert principals, requires structures for ensuring optimum growth for each intern regardless of their internship placement [9,33].

Variation in the tasks that mentors delegate to administrative interns and the level of support they provide influences how much practical knowledge each aspiring leader gains during their internship [6,11]. Through developing a better understanding of the principal mentor–intern relationship, principal preparation programs and school district leadership teams can gain an understanding of the ways to train principal mentors and enhance structures surrounding the internship year [7,9]. Research has found that interns should begin the academic year by observing their principal mentor; however, as the year progresses, interns should be provided independent opportunities to lead, with the amount of support principal mentors provide decreasing over time [6,9,10]. Mentorship has also been found to vary due to variation in how principal preparation programs establish expectations for the internship and provide training to principal mentors [28,32,34]. In addition, like student teaching assignments, programs may not always have choice in where interns are placed [35].

4. Methods and Materials

Our research sought to understand the phenomena of mentorship throughout the principal preparation internship experience. To do so, we ask: How do principal mentors influence interns’ leadership development throughout a full-time internship? Utilizing a phenomenological qualitative design, researchers examined how our participants’ experiences could help us make sense of mentorship in isolation and in terms of holistic themes regarding the essence of the mentorship [36,37]. The design allowed for the research question to be answered by the qualitative data supplied through the student interns’ reflective logs. Such rich qualitative data allowed for a robust understanding of the interns’ perception of their principal mentor and their mentorship experience using document analysis [36,38].

4.1. Data and Sample

The unique source of data were interns’ weekly reflections, which detailed the events that occurred throughout the week, how they would improve in the future, and their next steps for enhancing their understanding of the principalship. Upon submitting the weekly reflections, each intern had an executive coach and a cohort director that would provide guidance, feedback, and ideas for moving forward. All 22 interns were enrolled in the same university and completed their residency during the 2019–2020 academic year. With regards to training, principal mentors attended a half-day training from the university faculty team and received a comprehensive internship handbook outlining the university’s expectations for their role and relationship with respect to their intern.

Data collection was initiated when interns began submitting their weekly reflections in August 2019 and continued until the pandemic began in March 2020, with a few submitting the occasional reflection during April and May. Reflections were usually submitted to the program’s university supervisor sometime between Friday and Sunday night. Interns also received support from executive coaches—retired school leaders who support interns during their internship—who used the reflections to support interns and meet with interns’ principal mentors at least once during the semester.

4.2. Analysis

The weekly reflections of the principal interns are personal documents that provide details of the interns’ experiences throughout their residency [36,39]. We utilized the qualitative software Dedoose and Excel for coding reflections. The document analysis consisted of an initial inductive thematic analysis, where we looked for overall emerging codes related specifically to the phenomena of mentorship by examining interns’ experiences with their principal mentors [37,38]. After completing the initial coding, we met to categorize the emergent themes related to the interns’ principal mentorship experiences. These initial themes were interns’ autonomy, level of support, type and quality of tasks given, inclusion in the leadership team, and proactivity of the intern. Then, we analyzed the documents again utilizing deductive coding with six emergent themes [39]. The reflections were coded using the six themes, and we examined each theme at three different time periods throughout the year in which the reflections were written, namely the beginning, middle, and end of the year. We then determined how the emergent categories around mentorship took place and varied across interns. After the completion of this analysis, we reviewed the documents again to ensure coding consistency.

4.3. Reflexivity

In transparency with ourselves and our research community, we include our reflexivity as a means of shining light on the biases that each of us bring to our research [40]. Our intent is that by providing a clear overview of the factors that might influence our analyses, we were more capable of holding each other accountable throughout the interpretation process. Further, readers can consider such influences as they work to understand our findings for themselves. The lead author serves as an associate professor and an instructor for a principal preparation program. The second author serves as an assistant professor and program coordinator for an educational leadership preparation program. Prior to their current position, the second author participated in a year-long principal residency experience. Our final author served as a PhD student and research assistant for the project, with interests aligned with the project aims. Including multiple researchers coupled with our regular check-ins helped ensure that we worked diligently to limit the influence of our individual biases upon our research analyses.

4.4. Limitations

We note here a few important limitations to the study. First, interns varied in the amount, length, and depth of their weekly reflections. The range in interns’ weekly reflections was 18 to 37 (median = 29.5). The total number of reflections across the 22 interns was 766, and the length of response varied widely, from 300 to 1100 words. Second, due to the open-ended nature of the weekly reflection prompt—specifically, two open-ended prompts: “What is your reflection this week?” and “What lessons did you learn?”—interns were free to write about anything. That is, though interns often wrote about their relationship with their principal mentor, there was not a specific prompt asking them to document that relationship each week in their reflections. As such, some of the key themes regarding this relationship that emerged in the reflections were difficult to trace across the interns’ entire internship year. Finally, we only had access to interns’ weekly reflections and did not have the opportunity to ask follow-up or clarifying questions during or after their internship to the intern, mentor, or executive coach. Such an opportunity would have allowed us to clarify or confirm with the interns the themes that emerged in our data analysis.

5. Findings

Like Clayton and colleagues [23], we found that principal mentors played a key role in determining the quality of interns’ experiences, particularly in terms of the quality of work opportunities they received, as well as the levels of autonomy and support they enjoyed. Principal mentors set the tone of internship by determining whether the intern felt integrated into or isolated from the administrative team. Mentors varied in whether the intern received guidance and mentorship above and beyond day-to-day tasks. More specifically, our analysis revealed that interns’ experiences of integration or isolation were shaped by: (1) the types of tasks and activities they were allowed to engage in, (2) the level of autonomy interns were afforded, and (3) the support they received. Importantly, each of these factors were shaped by interns’ own proactivity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of the Key Findings.

5.1. Tasks and Activities

Part of enacting the role of principal relates to the types of tasks and activities that interns could engage in during their internship. Interns highlighted a wide variety of tasks that they participated in, which we categorized into four areas:

- Shadowing tasks, where interns observed their principal mentor or other school leaders conduct leadership tasks.

- A siloed task, where principal mentors assigned interns with one time-consuming leadership task, with little variation across the year.

- Low-level, routine tasks, where principal mentors assigned interns tasks that had limited opportunities for leadership growth.

- High-level, leadership tasks, where principal mentors assigned interns tasks that produced greater opportunities for leadership growth.

The difference between low- and high-level leadership tasks often related to the degree of responsibility (and therefore, risk) involved: interns who experienced opportunities to engage in high-level leadership tasks often reflected on the challenges, difficulties, and learning that accompanied more significant leadership assignments.

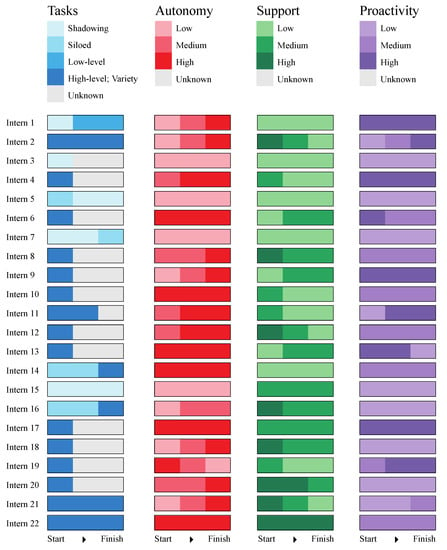

In Figure 2, we highlight the leadership tasks interns engaged in across the school year. For example, five interns shadowed their principal or other school leaders for part or all of the year. In many cases, these interns noted that these opportunities were important for their growth and development. One intern wrote, “The short week still provided a variety of learning opportunities as [my principal mentor] allowed me access to all the processes she was involved with. Her willingness to me being included is so appreciated and I hope to grow skills as impactful as hers!” Another intern reflected:

Figure 2.

Variation in Interns’ Experiences Across Time.

First, I had always wondered what kind of work principals had to do in their office that kept them from being in the classroom and in the hallways where they could be more visible. This week, I saw [my principal mentor] had to complete many mundane tasks that I had never thought of, like signing off on timesheets for non-certified staff.

Importantly, two of the five interns only reported shadowing activities in their reflections throughout the year.

Figure 2 also shows that four interns spent a large portion of their internship engaged in siloed tasks, such as student discipline, testing, or buses. One intern reflected:

I have been reflecting on how much of my time (and the time of many others in the building) is spent on student behaviors. Most days, I am not able to enter classrooms at all to provide instructional or behavior management feedback. I have brought this issue up with my principal mentor many times, but there seems to be no movement on helping in this area.

In fact, this intern’s reflection nearly every week included a discussion of behavioral issues at the school. Another intern, who formatted their weekly reflection with bulleted lists of activities by day, listed “worked with AP to manage dismissal and buses” and “monitored the cafeteria during A/B lunches” over 100 times. This intern was one of two interns who engaged in siloed tasks for a majority of the school year, with very few activities coded as a high-level leadership task.

In addition, many interns engaged in a series of low-level leadership tasks, such as hall monitoring, cafeteria duty, or data entry. While these tasks are an important part of school operations, they are often low stakes, offering interns little chance for leadership growth. One intern, for example, spent an entire day writing thank you notes for parents who attended a family engagement session. In reflecting on why it took so long, they wrote that it took a long time to locate a file with the school’s letterhead. Another intern shared their experience with an assistant principal, who had “been thinking about what I can give you to make my life easier.” She then asked the intern to alphabetize the referrals and put them in binders, a task that took most of the morning.

Finally, Figure 2 shows that 17 of the 22 interns had some opportunity during their internship to engage in high-level leadership tasks. One intern, for example, highlighted a leadership institute that they led only a month into their internship:

The majority of my week was spent planning for and participating in a three-day Literacy Institute. I worked closely with our literacy coach to work on this professional development. I taught many different brain breaks, closing circles/activities, and I delivered four small group sessions focusing on writing/publishing parties and on instructional read alouds.

Other interns had opportunities to conduct teacher observations, both through formal evaluations and informal walkthroughs. For instance, in September, one intern learned a valuable lesson from their principal mentor about taking notes during a formal teacher observation:

[This week] I completed two observations. They went very well and I had rich conversations regarding them with my principal mentor afterwards. I realized that when observing I took great, detailed notes. However, when I wrote comments on the actual evaluation form, I was less detailed. In talking with [my mentor principal] about it, I realized that I could write comments much like I would write IEPs—detailed and with evidence of what I observed (measurable). One of the teachers who I observed is the mentor coordinator for the school so she provided me with feedback on my comments as well. It was helpful to have a teacher’s perspective on this.

Higher-level leadership tasks provided interns the opportunity to actualize complex leadership skills essential to an aspirational principal position.

5.2. Autonomy

One intended purpose of the year-long, full-time internship is to allow interns the opportunity to practice the work of a principal by exercising autonomy and authority [41]. We found, however, that the level of autonomy interns experienced varied by degree (i.e., low, mid, high) and across time. For example, we defined interns with high-level autonomy as those who had full responsibility and little direction over the tasks they were given; many were encouraged to take on tasks they saw needed to be done without guidance from the principal mentor. From their reflections, these interns often learned by their own experience and through trial-and-error. We defined interns with mid-level autonomy as those whose principal mentor assigned them tasks with clear expectations and a moderate degree of oversight. Finally, we defined interns who had low-level autonomy as those whose principal mentors either gave them no tasks, low-level tasks, or tasks that were assigned in partnership with someone else (e.g., an assistant principal) who was ultimately responsible.

Of the 22 interns, 17 experienced high-level autonomy at some point in the year (Figure 2). Furthermore, most of these interns started with lower levels of autonomy at the beginning of the year, which increased to high levels by the end of the year. For example, after three months in her internship, one candidate described the high level of autonomy her principal mentor now provided her:

This week I realized how much trust my principal has in me to do some heavy lifting with research on student achievement and schoolwide initiatives. He gave me multiple tasks this week with minimal direction… He then told me how he often forgets that I am just learning because I am so resourceful and effective when given tasks that he wants to make sure that I am not feeling lost or overwhelmed.

In comparison, six interns started the year with high-level autonomy and maintained that level for the entire year. Only one intern started the year with high-level autonomy, which then declined as the year progressed—largely a result of the principal taking a more active role in her development but affording her less opportunities to lead.

5.3. Support

Along with variation in autonomy, interns also experienced variation in the degree to which they were supported by their principals. We coded support in terms of degree, from low to high. We found that half of the interns received decreasing levels of support over their internship, often from high levels to low levels (Figure 2). Eight of the interns received a consistent level of support, whether low (n = 5), medium (n = 2), or high (n = 1). Finally, three interns had increasing levels of support throughout the year. Importantly, we found that the types of support that interns received could be categorized by either mentor-directed support, intern-initiated support, or no support.

5.3.1. Mentor-Directed Support

Mentor-directed support often occurred through leadership team meetings, formalized check-ins, or other routines that principals established to support their intern. For example, one intern wrote, “Every Monday [my principal mentor] and I have a check in meeting. We share our calendars and talk about future events. It also gives us time to reflect on the previous week and speak about any learning experiences that I may have questions on.” Other support came in the form of principals providing direct feedback on interns’ performance, such as after interns completed a teacher observation or handled a student discipline referral. One intern commented:

I have been working very hard with [my principal mentor] on observations. She gives a lot of good feedback that has improved my comments and post-conference discussions. After struggling with observations, she was really impressed with the last one I completed. It felt great because instructional leadership is where I have the least experience.

Another reflected on his growth in student discipline, “Monday and Tuesday, I was able to handle all discipline as it came in. I spent some time with [my principal] on Tuesday where we reviewed some of the ways things were handled”. From later entries, it was clear that this intern’s mentor principal often initiated contact to debrief the activities of the day and offer guidance.

5.3.2. Intern-Initiated Support

In contrast, some principal mentors made themselves available to interns for feedback, direction, and guidance, but only at the request of the intern. For example, interns with principal mentors who provide a high-level of support felt comfortable reaching out to their principal mentors at any time during the school day when they had questions or needed guidance—even if the principal mentor was off-campus. In response, these mentor principals tended to provide explicit direction and guidance. For instance, one intern wrote, “I have decided that since our admin meetings have not really continued yet, I gather the questions I have and try to stop in at some point each day to check in with [my principal mentor] and ask my questions”. Another faced a serious concern with a student who had been cutting herself. Although her principal was out of town at her sister’s wedding, the student wrote:

A student told me that he was concerned for his girlfriend because she was cutting herself and had fresh cuts on her. She also apparently had three razor blades in her bag. I was not sure about the protocol, so I called the principal. She told me what to do and the counselor and I handled the situation.

Other principal mentors were also accessible to the interns, but instead of providing direct guidance, they tended to be a source of reflection and discussion for the interns to come up with their own decisions. For instance, after reviewing a discipline issue with a student, one intern wrote:

I feel that [my principal] and I have a strong relationship and I felt comfortable sharing my concerns [about a student] with him. He said I made a good point. We discussed the situation at length and agreed upon a course of action: 1 day OSS, teacher/parent/admin conference upon his return.

These intern–principal relationships seemed to be an important anchor for interns’ learning and leadership development.

5.3.3. No Support

Unfortunately, five of the interns found that their principal mentors provided little to no support throughout their internship. Often, the mentors were simply not available or accessible, preferring instead that the interns interact with the assistant principal(s). In one case, the principal mentor took a medical leave of absence for most of the school year; in another case, the mentor would not make time for the intern’s questions. She wrote, “My principal and AP are always busy…they are very rarely available for guidance, so I am on my own a lot”. Towards the middle of a school year, another intern wrote that his principal often worked alone, especially when it came to student discipline: “[The principal] has continued to manage the incidents almost 100% in isolation and little has been relayed to myself or the AP regarding his expectations to handle things when he is unavailable”. Importantly, interns with little support often recognized the need to be more proactive in receiving the leadership opportunities that would be most beneficial to their growth. The preparation program also had to move one intern who was consistently not receiving support.

5.4. Proactivity

Interns’ levels of proactivity played an important role in shaping the level of isolation or integration they experienced throughout their internship. Importantly, proactivity may have both influenced their experiences as interns and, at the same time, been influenced by their experiences. Sixteen of the interns’ proactivity levels stayed the same, with seven interns having low proactivity all year (Figure 2). Five interns had mid-level proactivity and four had high-level proactivity. Interns with low-level proactivity tended not to have assignments from their principal mentor or were only given assignments with little opportunities for leadership development. For the most part, low proactivity interns shadowed and observed their principal mentors or assistant principals (e.g., interns 5, 7, and 15; see Figure 2).

Interns with mid-level autonomy were largely delegated enough tasks and had enough autonomy that they were busy responding to the work of each day. These interns had principal mentors who established clear processes and procedures for checking in, but also allowed interns flexibility in how they handled their assignments. Interns with high-level proactivity actively took on tasks they saw that needed to be done, proposed ideas to their principal mentors, and often went above and beyond what was expected of them. Interestingly, interns with the highest levels of proactivity tended to have increasing levels of autonomy (e.g., interns 1, 4, and 9; see Figure 2), suggesting that their proactivity, in part, may have contributed to that increase. One of these interns, for example, established a routine early on with his principal: “Upon arrival each day this week I took the first few minutes to debrief with [my principal] and share key things that have come up. I mostly asked questions about his vision and expectations for different things.” Another described a time when her principal was out of the building, and she needed to step up:

This week required all hands to be on deck. [The principal] was out on Tuesday and Wednesday and I tried my best to support and step up with the team as much as possible. I handled a few classroom calls this week due to other administrators being tied up with observations and disciplinary needs. While addressing room calls, if I found myself unsure of the next steps, I would seek assistance and follow back up with the administrative staff to ask questions and receive feedback.

Importantly, principal mentors can play an important part in helping interns recognize the need to be proactive. For example, after completing a mid-year evaluation of the interns’ performance, one principal sat down with her intern to discuss the interns’ performance. The intern reflected on their conversation:

I was able to sit down with [my principal] and talk with her about my evaluation a bit…. For the most part, we are in agreement on my strengths and areas for improvement. She would like to see me be more of a “go getter”. She said she wants to be able to tell a principal when they call her that, “Once I get the lay of the land, I am able to see what needs to be done and do it”. It makes me nervous that I will not be able to do that. She says this is something I need to work on for the next few months.

Mentors’ encouragement of proactive behavior and pushing interns to seek out opportunities beyond those directly assigned helped ensure interns engaged in real-time problem-solving experiences akin to the realities of school leadership.

5.5. How They Work Together

Of course, each of these aspects of the internship do not operate in isolation. As we looked across these categories, we found a relationship between interns’ level of autonomy and support; most notably, as autonomy increased, support was likely to decrease. Nine of the eleven interns who had increasing levels of autonomy, for example, also experienced decreasing levels of support. This suggests that as interns and principal mentors gain confidence in abilities to conduct tasks, greater autonomy is granted and, at the same time, less support is needed.

Three out of four interns who had low autonomy all year, had low levels of support all year as well. Eight interns who started with low autonomy, but who received high- or mid-level support at the beginning of the year, had autonomy levels that increased throughout the year. Interns with high autonomy also tended to have lower levels of support throughout the year, in at least one case because of an extended absence of the principal due to health reasons. As highlighted in Figure 1 and discussed above, the interns’ proactivity often served as a means of influencing the interaction between the types of activities they engaged in, along with the autonomy they enjoyed and the support they received.

6. Discussion

One of the major benefits of the internship is it provides interns with authentic leadership opportunities [24,42,43,44,45]. The research literature suggests that mentors play a gatekeeping role by either opening doors and creating opportunities for interns to lead on their campuses or not engaging with them or focusing on their growth and development [46,47,48,49,50]. In our study of interns’ weekly reflections, we similarly found that interns’ opportunities to be integrated into, or isolated from, the school community were both enabled and constrained by their relationship with their principal mentors. Specifically, we found that the types of activities interns engaged in, their level of autonomy, and the support they received varied both across interns and throughout the academic year.

For example, interns who shadowed principals found that those opportunities were initially beneficial to their understanding of leadership; however, shadowing opportunities that extended across the entire academic year were less beneficial and limited interns’ opportunities to engage in high-level leadership tasks. Williams also found that internships were most relevant when interns could participate directly in leadership activities rather than merely observing [50]. Likewise, interns who were responsible for a single, siloed activity throughout the entire year tended to receive less opportunities for leadership growth, generally enjoying a degree of autonomy, but with low levels of support.

In contrast, we found that many principal mentors worked with their interns to create leadership opportunities characterized by high-level leadership tasks, where interns led professional development and conducted walkthroughs and observations. Importantly, these activities were characterized by a higher degree of risk. In another paper, we describe how interns benefited greatly from those times when other leaders were out of the building and the responsibility for the school fell solely on them [33]. In this study, we also found that mentor principals seemed to act strategically throughout the year by initially providing lower levels of autonomy and higher levels of support, then decreasing their support and increasing interns’ autonomy as the year progressed. Those interns who had mentor principals that established routines and procedures for regular check-in meetings, and then utilized those meetings as time for candidate reflection and feedback, also benefited greatly from the mentor–intern relationship [28,32].

Central to the successful (or unsuccessful) relationship was a foundation of trust that did or did not develop between mentors and interns. Other research has found that co-creating goals for the internship experience [19,30,32] and demonstrating trustworthiness by following through with assignments early are crucial to cultivating strong mentor–mentee relational dynamics [11,51]. In our study, we found that principal mentors who developed strong relationships with their interns were more likely to provide interns opportunities to engage in high-level leadership tasks, more likely to increase the level of autonomy interns enjoyed, and more likely to differentiate support. Importantly, the interns’ level of proactivity and performance influenced the degree to which principal mentors entrusted interns with high-level leadership tasks.

Of course, principal preparation programs and their district partners also play an important role in cultivating and developing the mentor–intern relationship. For example, preparation programs and their district partners might also consider the placement process for interns. Torres and colleagues found that principal mentors with very little experience did not create meaningful learning and leading opportunities for the interns [48]. Similarly, Bush found that interns received few opportunities for instructional leadership development from principals who were themselves weak instructional leaders [46]. In a longitudinal study of full-time interns in North Carolina found that internship schools had lower values on two different school working conditions measures (leadership and overall environment); had higher teacher attrition rates (in statewide models); had lower test proficiency rates; and were no more effective, based on student achievement growth, than schools that were not hosting an intern [52]. Though research does not yet examine the effect of serving in these types of environments on later leadership effectiveness, programs and districts can do more to consider and evaluate internship placements.

Programs and districts should also consider how interns’ experiences are shaped by other leaders in the building, including the assistant principal (AP). A recent review found that, while APs are uniquely positioned to promote equitable outcomes for students, their leadership roles vary considerably [53]. In this study, APs figure prominently in interns’ reflections; yet it is unclear what role APs can and should play in interns’ development. For example, APs who only use interns to “make [their] lives easier” by assigning low-level or undesirable tasks to them, as was the case with one of the interns in this study, are not providing a rich mentoring experience. In contrast, APs who embrace interns as an equal member of the leadership team and work purposefully to support them can enhance the mentorship interns receive. Programs need to be cognizant of situations where interns are primarily receiving their support and mentorship from APs, working to ensure that interns receive mentorship from their principal mentor.

7. Implications and Conclusions

Taken together, we believe these findings have important implications for policy, practice, and research. With respect to policy, states can play an important role in defining what constitutes a “high-quality” internship. For example, the state of Illinois requires that 80% of all activities conducted during the internship must be connected to high-leverage leadership practices, such as instructional leadership or human resource management; activities like bus duty or hallway monitoring are not included as part of these activities [22]. Such a policy could help encourage both principal preparation programs and their district partners to support high-quality internship experiences. In addition, states play an important role in determining different aspects of the internship, such as the number of required hours and requirements for supervision. For example, Anderson and Reynolds found that only 14 states required at least 300 h of field-based experiences, and only half of all states require that principal mentors be “an expert veteran” school leader [3].

States and districts can also support the implementation of high-quality internship in practice by working with principal preparation programs to co-develop and implement training for principal mentors. Research has found wide variation in the extent to which preparation programs train mentor principals, and high-quality training has been found to be associated with the quality of the internship [28,32,34]. In this study, principal mentors received an internship handbook and a half-day training from the preparation program. Though many of the interns were able to engage in high-level leadership tasks, act with increasing levels of autonomy, and receive support from their mentor principal, a few interns’ experiences provided fewer opportunities for leadership development. Districts and principal preparation programs can work together to establish expectations, co-develop assignments and leadership tasks, and provide training both before and during the internship to ensure interns are receiving adequate opportunities to grow in a range of leadership areas.

Of course, much of this work requires preparation programs to gather data throughout the internship to provide information on the interns’ development. In this study the program used weekly reflections to monitor interns’ experiences. Other work highlights the use of daily logs [41], surveys of principal mentors [54,55], portfolio analysis and feedback [56], and observations [57]. In gathering data, programs can also establish routines and processes for using it to support interns. Research on data use in education has consistently found that data gathering processes far exceed educators’ ability to use it [58,59]. As principal preparation program supervisors may have large numbers of interns to supervise, coaches may serve as an important resource in helping to gather data and provide timely feedback to interns. Coaches may also help to work with preparation programs to intervene when their principal mentors are ineffective or unresponsive to the interns’ needs [60,61].

This study also highlights the need for future research in several areas. First, as with the research literature on assistant principals more broadly, an open question for the field is how and the extent to which APs play a role in interns’ development. This study suggests that APs figure prominently in interns’ work; yet, as with research on APs more broadly [53], there seems to be wide variation in the types of roles and responsibilities APs have in the building. Second, the internship provides an opportunity for candidates to expand their network across the district [43,45]. Future research could use social network analysis to trace the development of these relationships for interns, following interns’ future placement and pathways through the principal pipeline. Finally, we know relatively little about the placement process for interns, beyond the persisting concerns regarding interns self-selecting their mentor and internship site [34]. In this study, placement varied by district, with some districts allowing principals to interview and select interns, and others matching principals to interns themselves. As the field works to diversify leadership pipelines, this match may be increasingly important in the development and retention of future principals [62]. Future research should examine the placement process, considering the ways in which placements enhance both interns’ and principal mentors’ leadership ability, as well as explore the ways in which the placement process may contribute to the development and future retention of principals of color.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A.D.; methodology, L.E.S. and L.I. formal analysis, T.A.D., L.E.S. and L.I.; investigation, T.A.D., L.E.S. and L.I.; writing—original draft, T.A.D.; writing—review and editing, T.A.D. and L.E.S.; project administration, T.A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Wallace Foundation, grant 580910.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of North Carolina State University (protocol code 19115, approved on 3 July 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Grissom, J.A.; Egalite, A.J.; Lindsay, C.A. How Principals Affect Students and Schools; Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Seashore, K.; Anderson, S.; Wahlstrom, K. Review of Research: How Leadership Influences Student Learning; Wallace Found: Wallance, ID, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.; Reynolds, A. The State of State Policies for Principal Preparation Program Approval and Candidate Licensure. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2015, 10, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; LaPointe, M.; Meyerson, D.; Orr, M.T.; Cohen, C. Preparing School Leaders for a Changing World: Lessons from Exemplary Leadership Development Programs; Stanford Educational Leadership Institute: Stanford, CA, USA, 2007; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, M.T. Pipeline to Preparation to Advancement: Graduates’ Experiences in, through, and beyond Leadership Preparation. Educ. Adm. Q. 2011, 47, 114–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, J.K.; Myran, S. Content and Context of the Administrative Internship: How Mentoring and Sustained Activities Impact Preparation. Mentor. Tutor. Partnersh. Learn. 2013, 21, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, J.K.; Thessin, R.A. Voices of Educational Administration Internship Mentors. Mentor. Tutor. Partnersh. Learn. 2017, 25, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, P.A.; Smith-Sloan, E. Apprenticeships for Administrative Interns: Learning to Talk like a Principal. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–22 April 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Browne-Ferrigno, T.; Muth, R. Leadership Mentoring in Clinical Practice: Role Socialization, Professional Development, and Capacity Building. Educ. Adm. Q. 2004, 40, 468–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, J.K. Aspiring Educational Leaders and the Internship: Voices from the Field. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2012, 15, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thessin, R.A.; Clayton, J.K.; Jamison, K. Profiles of the Administrative Internship: The Mentor/Intern Partnership in Facilitating Leadership Experiences. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 15, 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.; Wallis, M. Mentorship in Nursing: A Literature Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 1999, 29, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kariuki, M.; Franklin, T.; Duran, M. A Technology Partnership: Lessons Learned by Mentors. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2001, 9, 407–417. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, F.M.; Wallace, J.E. Mentors as Social Capital: Gender, Mentors, and Career Rewards in Law Practice. Sociol. Inq. 2009, 79, 418–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, C.A. Mentorship Primer; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2005; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, C.A. Critical Issues on Democracy and Mentoring in Education: A Debate in the Literature. In SAGE Handbook of Mentoring; Clutterbuck, D.A., Kochan, F., Gail Lunsford, L., Dominguez, N., Haddock-Millar, J., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- Daresh, J.C. Leaders Helping Leaders: A Practical Guide to Administrative Mentoring; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pease, G.E. A Delphi Study to Identify Principal Practices of Montana’s Office of Public Instruction Formal Mentoring Program for Principal Interns, ProQuest Information & Learning; Montana State University: Bozeman, MT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rolinitis, M.L. What Is the Connection between the Administrative Internship and Professional Practice? Ph.D. Thesis, University of St. Francis, Joliet, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Virella, P.; Cobb, C. Leader Developers: Perspectives of Mentor Principals in an Administrator Preparation Program. J. Educ. Superv. 2022, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartee, R.D. Recontextualizing the Knowledge and Skill Involved with Redesigned Principal Preparation: Implications of Cultural and Social Capital in Teaching, Learning, and Leading for Administrators. Plan. Chang. 2012, 43, 322–343. [Google Scholar]

- White, B.R.; Pareja, A.S.; Hart, H.; Huynh, M.H.; Klostermann, B.K.; Holt, J.K. Southern Illinois University, Illinois Education Research Council, University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research. Navigating the Shift to Intensive Principal Preparation in Illinois: Policy Brief; Illinois Education Research Council: Springfield, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, J.K.; Sanzo, K.L.; Myran, S. Understanding Mentoring in Leadership Development: Perspectives of District Administrators and Aspiring Leaders. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2013, 8, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geer, G.C.; Anast-May, L.; Gurley, D.K. Interns Perceptions of Administrative Internships: Do Principals Provide Internship Activities in Areas They Deem Important? Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Prep. 2014, 9, n1. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, D.L.; Valle, F.; Almager, I.L.; de Leon, V.; Gabro, C. Mentoring Job-Embedded Principal Residents. Int. J. Arts Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 2, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, W.G.; Sherman, W.H. Effective Internships: Building Bridges between Theory and Practice. In The Educational Forum; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 72, pp. 308–318. [Google Scholar]

- Schechter, C. Mentoring Prospective Principals: Determinants of Productive Mentor–Mentee Relationship. Int. J. Educ. Reform 2014, 23, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.S. Mentoring School Leaders: Perspectives and Practices of Mentors and Their Protégés. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Denver, Denver, CO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cosner, S.; De Voto, C. Using Leadership Coaching to Strengthen the Developmental Opportunity of the Clinical Experience for Aspiring Principals: The Importance of Brokering and Third-Party Influence. Educ. Adm. Q. 2023, 59, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geer, G.C. Addressing Reality: A Model for Learner Driven and Standards-Based Internships for Educational Leadership Programs. J. High. Educ. Theory Pract. 2020, 20, 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrich, L.C.; Hansford, B.; Tennent, L. Formal Mentoring Programs in Education and Other Professions: A Review of the Literature. Educ. Adm. Q. 2004, 40, 518–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, S.N. Mentor Principals’ Perceptions about a Mentoring Program for Aspiring Principals. Ph.D. Thesis, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, T.A.; Ivey, L.; Seaton, L. Principal Candidates’ Reflective Learning During a Full-Time Internship. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bost, D.N. An Examination of the Effects of State Level Policy in Changing Professional Preparation: A Case Study of Virginia Principal Preparation Programs and Regulatory Implementation; ProQuest LLC: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- John, E.S.; Goldhaber, D.; Krieg, J.; Theobald, R. How the Match Gets Made: Exploring Student Teacher Placements across Teacher Education Programs, Districts, and Schools. J. Educ. Hum. Resour. 2021, 39, 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billups, F.D. Qualitative Data Collection Tools: Design, Development, and Applications; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019; Volume 55. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G.A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P. Document Analysis. In Research in the College Context; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D.L. Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory Pract. 2000, 39, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, T. Learning by Doing: A Daily Life Study of Principal Interns’ Leadership Activities During the School Year. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2022, 17, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, C.J. Building 21st Century Education Leaders: A Multiple Case Study of Successful University-District Partnerships for Principal Preparation; Texas State University-San Marcos: San Marcos, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, A. Social Capital Development within a Novice District-Grown Principal Preparation Program: A Case Study of the DCPS Patterson Fellowship; ProQuest LLC: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. Understanding the Perceived Effect of a. Master of School Administration (MSA) Program on Instructional Leadership. Ph.D. Thesis, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rubens, J.L. Secondary Principal Internship Preparation Program: A Qualitative Study Focused on Twenty-First Century Principal Readiness. Res. Pract. 2019, 47, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, S.M. The Essence of the Principal Internship: A Phenomenological Study; ProQuest LLC: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, G.R. Internship Experiences for Aspiring Principals: Student Perceptions and Effectiveness. Ph.D. Thesis, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN, USA, 2011. UMI No. 3476276. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, A.C.; Bulkley, K.; McCotter, S. Learning to Lead in Externally Managed and Standalone Charter Schools: How Principals Perceive Their Preparation and Support. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2019, 22, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.H. Two Perspectives of the Administrative Internship; ProQuest LLC: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.R. The Intersection of Principal Leadership Self-Efficacy and Principal Preparation Programs: A Qualitative Investigation; ProQuest Information & Learning: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jamison, K.; Clayton, J.K.; Thessin, R.A. Utilizing the Educational Leadership Mentoring Framework to Analyze Intern and Mentor Dynamics during the Administrative Internship. Mentor. Tutor. Partnersh. Learn. 2020, 28, 578–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, K.; Drake, T.A. School Leader Apprenticeships: Assessing the Characteristics of Interns, Internship Schools, and Mentor Principals. Educ. Adm. Q. in press.

- Goldring, E.; Rubin, M.; Herrmann, M. The Role of Assistant Principals: Evidence and Insights for Advancing School Leadership; Wallace Found: Wallance, ID, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Koonce, G.L.; Kelly, M.D. Analysis of the Reliability and Validity of a Mentor’s Assessment for Principal Internships. Educ. Leadersh. Rev. 2014, 15, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.C. The Efficacy of a University Principal Preparation Program in the Southeastern Region of the United States as Measured by Educational Leadership Standards Found in a National Test, Internship Assessments, and Cumulative Grade Point Average. Ph.D. Thesis, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bowser, A.; Hux, A.; McBride, J.; Nichols, C.; Nichols, J. The Roles of Site-based Mentors in Educational Leadership Programs. Coll. Stud. J. 2014, 48, 468–472. [Google Scholar]

- Criner, K.L. A Descriptive Study of Local Grow Your Own Principal Internship Programs in Three Different Size and Types of Schools in Missouri; University of Missouri-Columbia: Columbia, MO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, T.A. Principals Using Data: An Integrative Review. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayman, J.C.; Stringfield, S. Data Use for School Improvement: School Practices and Research Perspectives. Am. J. Educ. 2006, 112, 463–468.s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappler-Hewitt, K.; Von Dohlen, H.; Weiler, J.; Fusarelli, B.; Zwadyk, B. Architecture of Innovative Internship Coaching Models within US Principal Preparation Programs. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 2020, 9, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarappa, K.; Mason, C. National Principal Mentoring: Does It Achieve Its Purpose? Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 2014, 3, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, F. Why a Diverse Leadership Pipeline Matters: The Empirical Evidence. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2022, 21, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).