Abstract

Less than 20% of the early childhood education and care (ECEC) staff members working in British early childhood centres agree that the inclusion of all children is an essential part of their working agenda, as they feel unqualified to take care of children with complex SEN or disabilities. This study makes a novel contribution by drawing on data compiled from a one-year ethnographic study which addressed the in-service learning experiences of seven teaching staff members that work inclusively. The participants included 2 classroom teachers, 1 SENCo (Special Educational Needs Coordinator), and 4 teaching assistants from a preschool class that teaches 92 children between the ages of 3 and 4, located in a primary school in England. We explore what professional learning means for the participants’ role, which professional learning opportunities are meaningful to them, and under which circumstances had been offered. This study not only does consider their opportunities for professional development on the job but also outside of work. The data were collected through semi-structured interviews, artifact analysis, and ongoing participant observation over one academic year. Data were analysed using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA). The results demonstrate that this case study offers a unique perspective of a microsystem that could be at risk due to a lack of awareness by leaders and administration. The study is divided into four themes that directly impact inclusive professional service-development practices: (1) challenges posed to continuous professional development by differing professional roles, (2) motives for in-service training: combining career, school, and authorities’ interests, (3) promotion of meaningful professional development experiences by school, and (4) self-determined classroom motivated by respect and recognition.

1. Introduction

Since the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Salamanca Statement [1], the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [2], and the Warnock report [3], early years inclusive education (children with and without special needs in the same learning environment with the early childhood education and care (ECEC) staff) has been a key goal for the British education system [4]. Scholars have identified skills and attributes that are professionally valuable for ECEC staff working toward the inclusion of all children, such as implementing quality practices [5] showing positive attitudes toward inclusion [6,7,8], engaging in collaborative work [9,10], and learning how to handle the complex demands of developing children’s potential while ensuring inclusion for all [11]. However, only 20% of ECEC staff feel qualified to work with children with disabilities [4]. In this paper, we aim to describe how the staff promote inclusion for children while also supporting their own needs as educators. Nevertheless, there is no documented longitudinal research following a group of ECEC staff describing their professional development experiences.

When focusing on their professional development, the demanding role of early childhood education and care (ECEC) staff must be considered. This topic has been explored in the literature, identifying a continuous change within the school as an organisation when specific professional functions are implemented [12,13]. Furthermore, when certain professional development strategies proved effective and obtained a fundamental sustained change in the ECEC setting, it was determined that the combination of practices resulted in combination among the early settings and broader systems [14,15,16]. In recent years, several scholars have analysed national policies or reviewed international reports that directly impact continuous professional development (CPD), offering normative strategies [12,17,18,19] and redirecting the educators into exclusionary practices [20]. Moreover, changes in any direction take the form of forces from within and outside the school that affect teachers’ practices and working conditions [21,22,23,24]. Scholars have identified challenges for ECEC staff in the more comprehensive UK early years systems, resulting from neoliberal policies on accountability [25,26] and austerity [27]. In some cases, these policies have resulted in schoolification in the UK’s early childhood settings due to the pressure placed on children being school-ready [28]. This effect is particularly expected at nurseries on primary school premises, such as the one in which the present study took place. In this regard, Rouse and Hadley [29] identified that staff only evaluate themselves according to the children’s academic performance, failing to account for the love and caring that they provide at the practical level. Scholars have also pointed out that burnout, high-stress levels, and turnover are general issues facing ECEC [30] and the numbers of staff affected by these issues have increased recently within the UK [31,32]. At the same time, the inclusion of all children means staff must adapt their pedagogy, content, and methods to the needs of each individual student, making it an essential part of the staff’s working agenda [17].

Having considered these challenging contextual factors, it is also important to explore the professional in-service learning and/or continuous professional development strategies acquired and implemented collectively by the staff as a team [33]. Professional learning occurs in various ways, including individual self-reflection [34], collaborative training or courses, or other less structured methods [35]. The present study is focused on exploring the professional learning that takes place either formally or informally [36] in a specific nursery setting characterized by the nursery “culture of learning”. Following Darling- Hammond et al. [37] and Egert et al. [38], effective professional development is needed to help teachers learn and refine the pedagogies required to teach skills to students to master competencies and achieve outcomes. Professional development also directly affects personal and collective well-being, including children’s outcomes [39,40]. As much as teacher–student interactions are essential, the relationships among staff are also critical to maintain quality ECEC [18,41]. Research on these professional learning communities in ECEC settings is scarce [42]. The idea of “co-production essentially indicates that the educational setting needs to move towards treating everyone equally but not necessarily the same” [43] (p. 134). The co-production of knowledge necessarily involves pupils [44,45] or children [46] and their parents working together to improve the children’s development and learning processes [47]. This co-production of community-driven knowledge occurs among professionals using their expertise [48,49], particularly to change the environment to one with more inclusive conditions [50].

In the nursery classroom from this study, ECEC staff must continuously carry out their work by “balancing, monitoring and adjusting” to each of the children’s needs and among themselves to maintain an open setting for feedback [51]. Since the introduction of the national policy framework for early childhood education (birth to five years) in England—the Early Years Foundation Stage Curriculum [52,53,54,55]—observations have been used to identify children’s interests, plan activities and educational experiences, and record achievements [56,57]. The research literature highlights that teaching assistants are in particular need of training in observation skills and reporting, meaning that teachers have the opportunity to guide context-specific school-based training [58]. In this article, we explore which strategies are the result of these interactions. As Zaslow et al. [59] state, the literature focuses on what teachers need to learn to achieve specific effective outcomes. However, few studies focus on teachers’ processes or strategies for learning and acquiring new knowledge or improving their practices. There is a need for evidence that focuses on the key dimensions and the pre-existing goals of on-site knowledge acquisition from staff participating in professional learning, the nature of their relationships, and the characteristics of these interactions [6]. Eraut [60] developed a theory on professional knowledge as a conceptual framework on adult learning at work which is applied as the basis for exploring how nursery staff learn in two schools and elucidating their learning processes. The author developed this theory to explore in detail the process leading to professional knowledge, including both the individual and the collective, conceptualising professional knowledge as a mixed construct by integrating social and personal aspects of the learning processes at the workplace.

The primary aim is to study the relationships among staff and children and communication of learning inclusive practices among school staff. Furthermore, we focus on the amount of time these individuals felt they were proactively contributing toward children’s social and academic inclusion [61,62]. Early years staff members’ first-person perspective on their professional process of learning to work in a classroom is under-represented within the literature on school experiences. By adopting the point of view provided by each employee as an individual, this study captures the real-life experiences of a group of staff members working together daily. Following the conceptualisation of learning culture, this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

- What does professional learning mean for the participants’ role?

- Which professional learning opportunities are meaningful for them?

- In which circumstances do these opportunities take place?

2. Research Methods

This is a qualitative research study [63] based on longitudinal ethnographic research carried out in a school on the outskirts of London, in the south of England, UK. Participants came from a primary school in the same nursery classroom (children from 3 to 4 years of age). This study has the limitation of the sample size, as it only represents a small nursery class among the entire English school population. Still, we point out that the goal of this study was to avoid generalising the findings, and the study validity was evaluated through the data being collected longitudinally. One suggestion for future research is replicating the study in other settings within multiple subcultural samples. Moreover, in this research, we analysed an in-depth and rich case, in part facilitated by a research team member that had already worked at the school and, therefore, we had the experience of starting this research with easy relational patterns of communication already established with the headmaster, the SENCo, and the head of the education borough city council. This nursery classroom was purposefully selected by the Department of Early-Year Education from the local university based on its positive experience with the students’ practicum over the previous 15 years. This study’s participants said that they were playing an active and essential role in guiding children’s success, individual needs, inclusion, and diversity [64,65]. Participants included one SENCo, two teachers, and four teaching assistants, who all worked with four groups of children. There were 2 groups in each time slot with 23 children in each group and space; therefore, there were 4 groups observed with 92 children included in total. Regarding the total of children with reports within the four groups, three children were diagnosed with disabilities, five with special educational needs (SEN), and four with English as their second language. The same staff worked one time slot of one session from 8:30 am to 12:00 pm and a second time slot of a session from 12:00 pm to 3:00 pm. The children from both classes participated in many activities together during the same time slot. Therefore, both teachers and teaching assistants shared spaces, planning, and activities. The group (staff and children) also worked five hours a week per time slot together with the SENCo as part of the coaching programme. All participants were female; six of them identified their ethnicity as white British and one identified as Asian British. All participants were given a pseudonym following research ethics. The background details of the study participants are presented in Appendix A. Before the interview, participants received an information sheet, a consent form informing them of participants’ anonymity and protecting the confidentiality of interviews, and the interview schedule and guide (Appendix B).

A total of 28 semi-structured in-depth interviews were held (4 per participant, lasting around 1 h each) with the 7 participants: Alice, Anna, Emmy, Ellen, Andrea, Mary, and Dory (Appendix A). This process offered them more time to reflect on their motivation for their continuous professional development (CPD). Additional participant observation took place during the academic year (2018/19) in two batches of three months of daily visits, one from September to November and a second one from April to June. In addition, the first author engaged in informal conversations with the children, school staff, and parents. During the teaching sessions, the first author took the teaching assistant role. When the class teacher was leading the class, she was the one observing, and she sat at the back of the classroom to take field notes, and also observing while in cooperation with the classroom staff she was an active participant by joining pupils’ activities during in-class group work and after-class activities. Data triangulation was accomplished by analysing the collection of artifacts [66] such as photo-based diaries and children’s evaluations and reports. Ethical approval was granted by the Anglia Ruskin University Ethics Committee.

3. Data Analysis

The interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) approach explores participants’ personal life experiences [67] in a sample from a homogeneous group and analyses how they make sense of these experiences. The researcher’s role is to analyse and interpret the participants’ attempts to understand their world [68]. These data analysis methods have previously been used in education to analyse teachers’ experiences when implementing a new research method [69], or when teachers and teaching assistants were working with children in minority groups [70]. IPA is structured as a research method, including a clear definition of sampling, data collection methods, and analysis [71]. First, the researcher works with one case (participant), and then the other one, and so one. When the individual interpretations are made, cross-case analysis is conducted based on the themes of each participant. As the goal of IPA is not to generalise the entire population, a small sample of 5–10 participants was selected [68]. In this regard, scholars have suggested that to create a specific generalisation, it could be helpful to compare different studies on a particular problem in future research [71]. Brocki and Wearden [72] suggest including more acknowledgment of analysts’ preconceptions and beliefs and reflexivity. All information was transcribed verbatim, and the participants were given the opportunity to review the data from the interview transcripts. They also participated in the coding of said data into themes and subthemes [73], codes, which were categorised into experiential clusters [74]. The initial themes were analysed for association to identify any differences and similarities between them and form clusters for themes. Then, similar themes were grouped to create a master list of themes [75,76,77]. All data were evaluated using NVivo. The first researcher had five years of experience working as a head teacher and SENCo in a British nursery school, ten years tutoring students during their student teaching period at different universities around Spain and the UK, as well as experience as an active researcher at several European agencies.

4. Findings and Discussion

The following sections respond to the research questions concerning how and in which conditions the staff identified professional development opportunities related to the inclusion of all children and strategies that worked for them which they had acquired and implemented to specifically cater to the needs of individual children. The first section presents the barriers that respondents identified and specifically pointed out the challenges of communicating them to the community of learning. At the same time, the opportunities for the school of staff are growing their capacity of professional development and conditions such as spaces and shared time. The second section transitions from the macrolevel, in which school was the main theme, to the microlevel in the classroom and how the staff feel about the main actors. Finally, the third section presents essential details to describe how the staff also introduce their experiences and opportunities to research and learn outside their work schedule.

4.1. Challenges Posed to Continuous Professional Development by Differing Professional Roles

Addressing the first research question in this section, the professional development related to the specific roles of the staff depended on the specific working conditions of each of the respondents. In contrast to the international literature, such as that of Sharma and Salend [78], in this nursery classroom, the professional roles were clear and defined in a school document available for all staff. Participants highlighted differences in their working contracts, stating that educators have static definitions of their roles. According to their interpretation of the working profiles, some staff were the leaders, and some were the assistants, as asserted by Peeters et al. [19]. Not only did this hinder the implementation of professional learning, but it also impeded it. Moreover, the staff’s duties were influenced by the corresponding type of work contract, as was also identified by Duckett [79] and Webster et al. [80]. As stated by Basford et al. [81] in the classroom, the lower the qualification the staff have, the higher the chance of being delegated cleaning duties. The teaching assistants’ unstable, underpaid, part-time working contracts sometimes reduced their interest in further training outside their working hours. They highlighted that they worked only the hours stated in their contracts. Apart from their working contract, in terms of acknowledging experience and competencies, Andrea and Ellen had the crucial role of working alongside the teachers. Anna expressed: “The teaching assistants that are studying to get a teaching degree never did the washing up!”. Furthermore, teaching assistants highlighted being undervalued by the government and fear of their roles disappearing to be replaced by less-qualified personnel, highlighting that the government views their role as simply providing “cleaning services”.

Another example of the static, structural aspect of power in this organisation is that teaching assistants’ duties impede them from participating in school INSET (in-service education and training) days. There was a widespread understanding that the teaching assistants (TAs) “choose” to prepare for their classes before children arrive rather than participating in the training day. This was widely accepted by the rest of the staff working at the nursery.

As for contractual issues, their contracts were defined by law and complied with. The teachers Alice and Anna had full-time contracts based on nationally agreed-upon working conditions for state schoolteachers. According to Alice, they worked “without specific working hours”. This statement aligns with the national data reported by Allen et al. [82] which showed that teachers took work duties home with them, mainly administrative tasks. What the staff highlighted and agreed upon regarding austerity measures coincides with what Elfer et al. [83] describes as the disparity of their formal duties resulting in exhaustion and feelings of being overwhelmed in their free time due to their workloads. The group stated that they did not have enough time for planning or research during their working hours. Alice explained: “I found that this job takes a lot of time, and when you have got young children as well, it is tough to balance everything; you can’t know everything about everything. You have to sort the line somewhere at the time that you are doing your work properly, and you are serving your children well. Sometimes the research has to go to the back until you are ready. This job’s straight out too much for me”.

4.2. Motives for in-Service Training: Combining Career, School, and Authorities’ Interests

This second section addresses the second research question which defines the activities that are meaningful to the participants. Participants felt that school and local authorities reinforced and supported their studies and career plans through formal and non-formal learning. The strategies indicated below were vital for identifying the training needed at the nursery classroom. The school implemented formal training that caters to staff and children’s needs, including the understanding of children’s identities, a culture of belonging and active participation, specialised knowledge, learning from experience, and motivation to succeed.

“I have been fortunate in this school. If I weren’t in this school, I wouldn’t have this amount of training…. So, I will just be put into the role, and I would like to learn just as I go along”, Alice comments.

The personal development reviews, referred to as personal development plans (PDPs) in the academic literature [84,85], constitute an innovative practice implemented in the early years education. In this specific school, the plans were utilised by all the school staff who set their training targets for themselves along with a mentor (senior manager) for the following academic year. They assessed their performance during the year; Mary stated that staff had the chance to share what they felt about their professional learning progress in the parameters that had been defined in the prior year. All staff felt that this coaching was beneficial when it was based on trust, confidentiality, and honesty. Having time to reflect on their strengths and capacities, Anna stated:

“It is helpful to stop and think about the year which has just passed. Sometimes you are too busy to stop and look at what has or hasn’t been achieved and how the activities are progressing. It is good to have the opportunity to reflect on the academic year and how it has affected each child”.

Mary stated that she felt confident when she spoke with the mentor, “as it is all confidential and you can say whatever you like”. She also said that the help request training and sort out any difficulties. Respondents highlighted that the practical training courses best addressed classroom needs. As Anna noted:

“When I had these two little boys, I went to a beneficial autism course. I chose to go there because I wanted to do the best for this little boy and because he was so severely autistic. It was like he was in his little world. We wanted to break these barriers and integrate more. He is still in this school, and he said, “Hello Miss”, and the chat started to be more forward. That course was beneficial, and it still runs now”.

Staff were told to set targets and goals together at the beginning of the year, and they completed the review of the previous year along with the plan for the following year. For example, Emmy said she would seek out an incremental programme for the collaboration of teachers with teaching assistants, a plan on maths for the half term, as well as the teacher plans to perform the evaluation with Anna to make recommendations to teachers and demonstrate examples of good planning. Emmy read through the reviews, looked at the training needs, searched for courses, and laid out what was required. Regarding one aspect, ten staff asked to complete first aid training together, so it was decided that this training would be provided to everyone on INSET day. In the end, the entire nursery staff was happy to have participated and shared the experience with colleagues.

Only a limited number of training courses were compulsory for all nursery staff and planned outside working hours. These included religious education studies (the school was a Catholic school), health and safety, Makaton instruction (language and alternative communication programme that mixes signs, words, and pictograms), and computer training on an interactive whiteboard. For example, on Tuesday evenings, Andrea, Mary, and Anna participated in a course in speech and language that specialised in attending to children who “could not communicate clearly” in order to “avoid the frustration and help us understand the child”. Emmy had completed a Makaton course 15 years prior to that time. Given that a course was offered every term in the borough, she considered that it would be valuable for the assistants to attend as well and decided to include this training as compulsory. Not only did they enjoy level one, but Ellen and Dory intended to sign up for advanced Makaton, as they felt it could help children with their speech. Level one was compulsory, but they felt motivated to ask for further training. According to school staff, including teaching assistants and teachers, employees were pleased with their borough, and they had always received the training they requested. Emmy praised the local council’s performance in offering good advisory support from its learning support service. As she stated, “[those who advise] us about children who have difficulties [make] direct contact with all the teams… phone them, email them and the support teacher will come to school. They do [this] each term”.

The inclusion development programme [86] was a government strategy that was implemented in the nursery beginning in June 2011 and focused on supporting children with behavioural, emotional, and social difficulties. Emmy led the report on training for the staff from the nursery and collaborated with them to decide which targets should be included. The information increasingly grew, “like a snowball”. Training on how to treat children with severe allergies is an example of this programme’s components. This activity consisted of a compulsory 30-min training that was required every year for all staff and completed on workdays. It involved watching a video and learning how to use the anti-allergy pen with a nurse. Mary pointed out that the training was initiated because there are always children with severe allergies. Additionally, it is compulsory that one of the staff members in the nursery have first aid training annually, and teaching assistants—Ellen, Andrea, Mary, and Dory—had completed speech and language training in the early years foundation programme. The borough was also linked with the Institute of Education, University of London, which offered free training courses to the staff once the school had subscribed. For example, one week Anna attended training on judging the impact of interventions.

If Andrea, who had a university degree, wanted to be a teacher in this school, she would be offered the postgraduate teacher education (PGCE) free of charge. Andrea said she was fully supported during this one-year learning period, noting: “It is in the interest of the school for me to take this route. I am teaching and doing the observation and going to the regional training centre once a week. The school has my timetable, and they know where I am every day. They pay for me as an unqualified teacher, and I am working for the school from 8 to 4; hopefully, at the end of the year, they will increase my teacher time, and then in the summertime, I will do nearly 80% teaching. I will have another teacher with me, and the maximum is 30 students per class. When I finish, I will be a qualified teacher, as normally it is one teacher per class plus one teaching assistant. I have a mentor who works with me in the personal development review (PDR)”. Therefore, the school was again allowing cheap labour, as they were not paying for the working hours of staff that were taking part in the praxis, and the school was also paying a trained teacher a lower salary, as an unqualified teacher, when that person was taking part in the practical training period.

4.3. School Promotes Meaningful Professional Development Experiences: Non-Formal Learning That Made the Staff Reflect

This third section addresses what actors identified as the professional development activities that they valued as meaningful. Within the non-formal learning components of professional development [87], staff received diverse training in interactions and planned meetings or workshops. Some ideas resulted from Emmy’s classroom observations. For example, Anna stated, “[Emmy] often comes down and sees how they were managing”, and this led to suggestions. The teachers had more opportunities to meet than the TAs, such as during the Monday and Wednesday meetings for teachers. Alice explained, “We have a formal meeting each Monday. For example, we had one on planning. We brought a piece of paper with our planning together, and we discussed how to make it better, where do you get that from etc. As a result, we had a staff meeting this week on stress awareness. A lady from the borough came here to talk about what being stressed is and what to do if we are feeling like this, and another was about writing. The managerial team decided on the topic because it is the need of our school”. She also pointed out that “if it is a whole day course, it has to be approved by the head teacher, so she gets a cover teacher for you”.

The staff said that the school had promoted workshops outside working hours that responded to classroom needs but did not lead to any certification for participation. In addition, the school collaborated with external training sources, offering programmes a few evenings per month, with training provided by external people. Only teachers and Andrea participated (i.e., experts on behaviour modification). The staff stated that these experiences positively influenced their practices, as they required them to take a step back from their work and reflect. The adversity of attending outside working hours results in the TAs’ non-participation. Emmy said:

“I have tried to persuade teachers and teaching assistants to participate in the training in the evenings. This expert gives some examples, and everybody who goes says he is such a good speaker. Of course, it is a long evening, as it is from 6:40 to 8:45 at the end of a working day, but everybody said that the time went by quickly, as he was outstanding”.

The differences in their motivation to participate were shown depending on the mobility of their position within the organisation. This statement is linked to research by Klu et al. [88] which confirms that those who are motivated to obtain further training do so with the prospect of finding a more senior position.

Anna and Andrea thought that the choice to learn about creative curriculum was helpful for them, noting that “instead of using a book, they thought about how to apply that into music and drama, and it allowed children to find information more creatively”.

The school also promoted staff’s visiting outside schools during their working hours, and the four teaching assistants appreciated this initiative. For example, Ellen said, “[We visited] if a group from another school had set out a new outside playing area or implemented a new teaching strategy, thus enabling each school to learn from each other and keep an open mind to new ideas”.

The nursery class’s activities were linked with those of the reception class (children from 4 years of age)—the students one year above the nursery level—to facilitate their transition to the following year’s classroom. The literature on early years education supports the importance of smooth transitions [89]. For example, both groups had an assembly together at Christmas. After February, ten children went to reception, and a few weeks before as part of the transition plan, they were playing with the next year teaching assistant during the break times. The staff worked together in creating a curriculum that matched the children’s needs.

Staff also highlighted that through the local government’s school system, the school has a private website for staff that they use to share content “with the school community. They had access to the policies, parents’ letters and online training”. In addition, on the website, parents can chat with them and send them direct messages and normally receive a response in a couple of hours; staff were proud of their fluid communication.

Teachers and teaching assistants meet on INSET days. They agreed that these were effective for learning about inclusive practices, such as the strategies of McElearney et al. [90] and other compulsory training meetings promoted by the school leaders. The INSET days were approximately five days per year in the academic calendar, designated for mandatory training for all staff and, therefore, the school was closed to the children. The team knew the dates through the annual calendar and from the briefing at the teachers’ meeting.

Moreover, Emmy, the schools SENCo, visited the nursery class once per week, following her specific school’s regulations. She also pointed out how health through the Education, Health and Care (EHC) plans and in-nursery pedagogical goals correlate. The staff described themselves as active in the elaboration of national policy and actions. They said to be involved in national questionnaires about the impact of policy on practical action. At the same time, Emmy pointed out that policies are still underdeveloped in standard procedures [91] she said that follow up the cases within the school described by Whalley [92] research study as fundamental inclusive research in the article “A Tale of Three SENCoS, post 2015 Reforms”. In contrast with the general norm highlighted in previous studies [93] Emmy said that she never found herself working alone. Early intervention was a school aim, and, as research shows mentoring to be a key method of delivering informal learning [60,94,95,96], she mentored Alice as the school’s deputy SENCo. Alice was mentored by Emmy in weekly sessions each Wednesday afternoon at the school, and she performed her role of SENCo alone on Friday mornings. The process would culminate when the SENCo retired, at which time the teacher Anna said, “she would take the lead”. She highlighted her pride in seeing Alice implementing the strategies that she had learnt from her in the nursery classroom. She also felt satisfied and pointed out that the working hours were appropriate for school duties. The programme was promoted by the borough and took place outside working hours, once per month in the evenings. Alice was mentored in weekly sessions with Emmy each Wednesday afternoon at the school, and she implemented her training on Friday mornings. She confirmed that she would have annual reviews by the local council. Furthermore, she had access to an online INSET of 8–12 h that provided online training for teaching children and young people with SEN. She said that the training was expensive, but she would apply for economic support from the national SEN funds available from the National College for Teaching and Leadership (NCTL). Alice felt certain that she would obtain that funding, and that what she was learning was very valuable. She had to read about the latest governmental publications related to SEN learners and prepare multiple case studies based on the school experience. The school allowed her to go to the training offered by the local authority during working hours, and the classroom teaching assistants covered her duties.

This case study showed that the staff’s continuing experience of learning about including children with SEN was linked to the progressive implementation of inclusive school policies, such as the system identified by Tharp [97] in his book. Staff confirmed that their role had developed from directive teaching methods to leading play activities based on changes in their pedagogy. Furthermore, the policies influenced the staff’s infrastructure and materials for each learning situation, and teachers and TAs felt empowered to participate in the national level white papers review. Other facts related to the legislative implementation included incorporating the professional knowledge and experiences of local government professionals who worked externally with children with disabilities in classroom activities and among the staff from different pre-primary year classes (Foundation Stage). This collaboration was implemented through meetings and programmed visits from social workers, psychologists, and speech therapists who came to the class to intervene during the regular schedule of activities. The benefits were that the parents became familiar with the adaptation strategies used in their children’s classes, and the nursery staff learnt from the experiences of staff who had previously taught the children and saw the need to adapt to the new children’s environment. They all worked as a team, which supports the findings presented by Peeters and Sharmahd [98] in their case studies.

The collaborative work among the SENCo for the children with SEN included previous nursery staff who elaborated a detailed individual educational plan (IEP) for these children, including social IEP objectives [99]. Therefore, the resources were already in the nursery classroom when the child began attending the school. This evaluation of the transition process correlated with Kemp’s case study [100] and Schischka et al. [101], who had also described the importance of the level of support provided and the participants’ collaboration. The case study conducted by Stormont et al. [102] also explored the value of sharing children’s information; as a result, at this school, parents were responsible for making copies of these reports and sharing the knowledge with professionals. Following the recommendations by Kemp [100], the staff’s training in this case study was documented and coached during visits to the teachers in the previous preschool setting. In keeping with the work of McIntyre et al. [103], the multidisciplinary team involved parents in developing the planning, including their own cultures and world realities, and bringing them to the classroom, where strategies, goals, and objectives and support were developed. Instead of including a psychologist as the head team leader, Alice, the teacher of the three children identified with SEN, and who takes daily responsibility for them, took the lead in this case study.

4.4. Shared Culture of Learning about Inclusion: A Self-Determined Classroom Motivated by Respect and Recognition

Several factors contributed to resilience and protected teachers against stressful circumstances. For example, all staff felt self-efficacy in implementing their practices; they perceived their abilities to affect children’s behaviour positively. Consequently, they have defined themselves as a collective through self-determination, resulting in self-governance in the nursery classroom. They stated, “All. We’re doing it all”. Teachers explained that they used the documentation, met together at the end of each session and, for instance, took photographs of a child who displayed challenging behaviour, such as not engaging with others. They also used photos and notes to help them to contextualise the information after writing down the observations in the children’s profiles. Ultimately, they all were satisfied with their performance [104].

All nursery staff agreed that collaborating, as Hargreaves [21] highlights, is part of their role, stating that they had been “working in this way” during their 30 years of combined experience. In this regard, Webster and De Boer [80], highlight that the practice of collaboration is a natural phenomenon at schools in England.

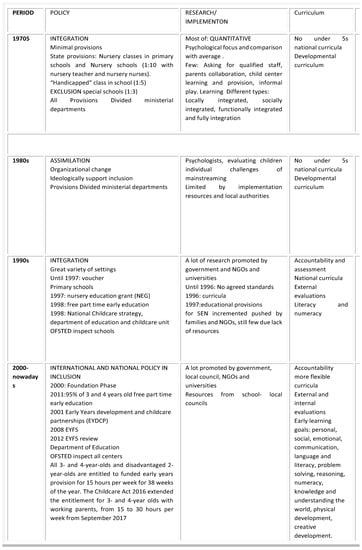

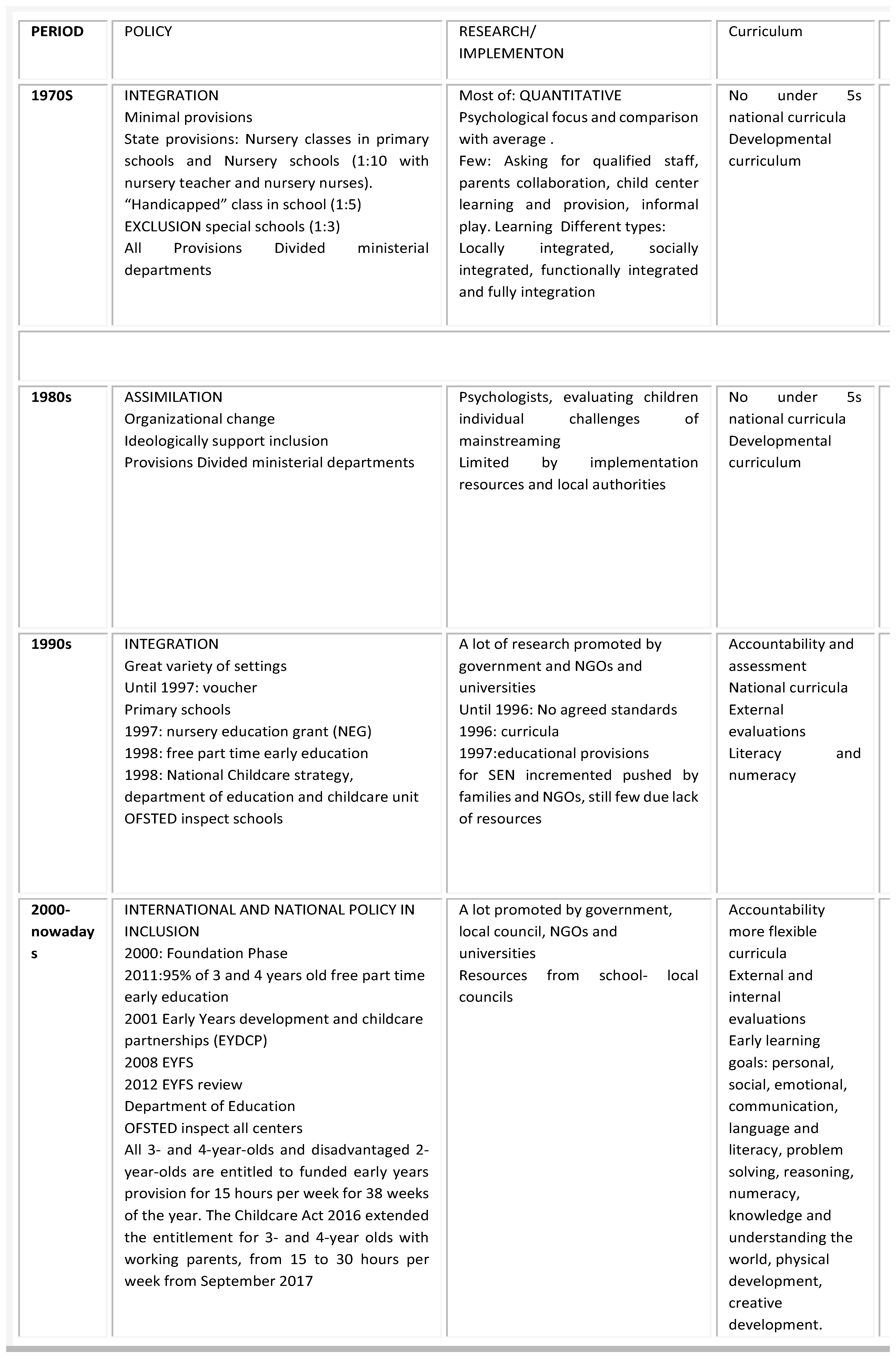

In Appendix C, there is a summary of the historical path of inclusive education at this school. The document was elaborated based on the experiences of the staff participants and shows that the collaboration among TAs and teachers is clearly defined by the teachers’ attitudes toward education and care roles.

Regarding the implementation of reversing roles and skills for teaching younger children acquired from the learning support assistant [105], Anna said: “A couple of their ladies were nursery trained and very experienced with children from birth to four. The TAs were excellent in the toilet training and hygiene area. They contribute to the planning, and some of their ideas were brilliant. They tried to work together as much as possible”. At the same time, Alice acknowledges the TAs’ key role in taking responsibility for the children’s achievements and “making a difference in children and families” [106]. Alice states that she had always known—since her years of studying at the university—that she would have to work with teaching assistants. In her work, she had “to manage them and the class”. Although both teachers felt like managers in the staffing structure, we observe that this became a distributed form of leadership [107]. Teachers confirmed that working together with the TAs was helpful, mainly supporting children’s inclusion.

In contrast with the data collected by Mackenzie [108] in primary schools, TAs in this nursery thrive when working together with the teacher in group lessons implementation, not only as an individual service for children with SEN. As Bowles et al. [109] highlighted, teaching assistants, in most cases, are not qualified teachers and need this training to increase their collaboration with teachers and other teaching assistants and implement more inclusive practices. In this classroom, they did that through mentoring. Teaching was also a TA function; according to Emmy, the nursery class had been implementing a system promoted by the headmaster to use the TAs to work with an entire class and the teachers. At the same time, supporting the findings of Ingleby and Hedges [110] all the research participants agreed that they had felt that they needed further training when they started working at the school. They stated that their previous formal education had insufficiently prepared them for fulfilling the daily competencies required at the nursery. In fact, the views of the staff in this study corresponded with those of 90% of respondents to the BAECE (British Association for Early Childhood Education) survey—which supported the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS)—stating that they felt “very confident” in their understanding of the EYFS [58]. The significance of this aspect of the study is that it indicates that staff acknowledge their potential and wish to expand it. These comments by staff align with the declaration of nursery staff in “Narratives from the Nursery” regarding negotiating professional identities in early childhood education. Specifically, these team members reported that they “use critical reflection on subjective experiences and value its implication in their practices” [111] (p. 152). Staff value the power and the importance of attachment in early childhood education. However, as is highlighted by Page and Elfer [112], there is a lack of recognition of the inclusion of emotional experiences (i.e., respect, empathy) in the daily observation of children, practices, or curricula that could be further explored by scholars.

Nursery staff proudly explained that one of their primary roles was planning and delivering pedagogical resources. Following the implementation of these training strategies, teaching assistants felt valued by teachers, and they acknowledged the programme’s value in some of their practices, such as planning resources. For example, the teacher had informed teaching assistants that they were to plan the materials needed for the following academic year, and the TAs checked which supplies they had available and which ones they would need to buy. In addition, part of the daily practices was based on recognising prior knowledge and experience. Nursery staff learnt based on their experiences and curricular areas and by collectively reflecting on their teaching and on their students [12]. Both teachers said that they loved to plan and offer multiple choices to children. Teachers highlighted having prepared a schedule for each activity, which specified the objectives, curricula, and class materials needed. In 2007, when Anna started to work at the nursery, she began to put together all the information about activities in a file in the database. Anna said that this simple solution avoided arduous work and time-consuming experiences and offered continuity to their project. Therefore, staff had their memory book, named “nursery foundation stage”, in which they elaborated upon their previous experiences. It was in a Word format, and they created a folder with examples of activities linked with the areas from the foundation stage. They said that they responded according to the children’s reactions, indicating whether they were interested in the activities. The database was elaborated following the six main areas of development, and staff indicated the learning objectives, experiences, and provisions that children would gain from the activities. Alice said that this information “is necessary or exciting because we balanced the specified curriculum with [the students’] ideas and then adapted these and reused the activities concerning their needs and interests”.

4.4.1. Non-Formal Learning as Continuous Training inside the Nursery Classroom

The following are the valuable professional learning strategies in this nursery, as defined by the staff members: modelling [40,113]; work discussions [27,83,114]; mentoring [115]; and relationship with parents and visiting families’ homes. As Eraut [94] explained, nursery staff identified that they were acquiring professional knowledge through direct experience, being co-learners and reflecting on their experiences. Particularly, class teachers appreciated the training received and, even more so, that they could practice it as explained by combining course work with individualised modelling and feedback from interactions with children. Teaching assistants decided to model activities and teaching strategies (i.e., Makaton) that they had implemented with the children [116]. Nursery staff used the internet in the PC located in the nursery classroom to visit resource websites, such as “Twinkle”, and printed materials out at lunchtime. At the school, nursery settings were prepared in keeping with school guidelines, and staff both met and taught in large or small groups. Within these groups, they observed and modelled the pedagogical strategies of each other as a helpful tool for inclusion [117].

For three years, the TAs and teachers had been completing observation reports on all the children. If teachers made certain observations about a child from a different group, they would take down relevant notes and later explain them to the teaching assistant who had that child under her charge. They also took turns doing individual activities with the children with SEN, which all the assistants enjoyed, as it gave them a chance to see how the children were progressing. Mentoring was implemented at all levels; the teaching assistants followed the teachers, or when performing the Makaton or the social communication service, the team performed the peer mediation training with the TAs. The parents’ helpers and the students from the high school were also mentored. Both groups of people were volunteers at school.

Staff said that they had good communication with the parents, maintaining a positive partnership, and parents were involved in the day-to-day basic scheduled activities, many of them as parent helpers [118]. This kept them involved in the progress of their children’s learning of new vocabulary and new goals. Parents were even sometimes asked to contribute to activities by bringing objects from home. Further information was provided through a monthly school letter in which the headteacher wrote a few words of thanks to the school community and highlighted the month’s primary activities. Staff established a schedule of parents’ consultations and informal meetings for parents with children with SEN: the IEP meetings were for the three children with SEN. They met formally, approximately every two months to discuss the plan and share their portfolio and artwork. Both class teachers were the key contact people for the parents of children with SEN or at-risk children, and parents could speak with the individuals when they collected their children from school. The school planned one parent evening per term, and parents were informed by letter, two weeks in advance, as to when that would take place. Parents knew that there would be one in October, one in February, and one in July. The times were scheduled by Alice, who tried to arrange them around parents’ work schedules. In July, children brought their folders with what they had completed during the academic course, some of which had been finished in the nursery and others at home.

Regarding this topic, participants described a culture of learning from children’s achievements. The participants expressed positive experiences of building learning culture based on children’s progress.

Alice observed:

“Nursery is a completely different place to anywhere else in the school because it is usually the first place a child has been left without their parents. When they arrive at nursery, they often do not know how to sit and listen, cross their legs, follow instructions or how to focus. They also don’t know what we expect from them. So, our first aim is to get them accustomed to these basic things so that they will be prepared for the next level”.

From the students’ first days at the nursery, staff performed the activities “with love and passion” and observed how children reacted to the new environment. Specifically, the children in this class were three years old by September. They worked progressively, and by the second term they began sharing activities with the children in said school year, known as reception. Teachers had a chart displaying the children’s birthdays and home photos. Staff were fully involved in the activities, and communication was constant. The children decided when it would be music time, and all the staff got involved and danced and sang. Additionally, when they were preparing a pool of mud at the outside area, everyone participated, and children were cleaned up when they got too dirty. One teaching assistant had pre-prepared different coloured petals made from cardstock to create flowers, others had a play-dough activity area, another had plant pots and water cans prepared, and there was a sandpit area with activities.

Nursery staff communicated happiness through empathy and the acknowledgement of child development, culture, and growth. Since the beginning of the academic year, staff had been implementing continuous formative evaluations and follow-ups for all the children. Alice expressed how proud she was that:

“all children with SEN had come such a long way. They had been doing a lot of facial exercises and pronunciation, a lot of individual work, peer work and group work, they knew a lot of words now, they were communicating well, yet when they came into nursery, they did not have any language. The child (C) has come a long way as well; he is more communicative and understands a lot more, using the advice of the speech therapist and the psychologist”.

The staff members agreed on structuring time and resources in a flexible schedule. Staff highlighted the ways in which changes in policies at school offered them the opportunity to plan inside and outside the classroom [119], therefore creating more opportunities for children to learn, mainly through scaffolding peer-to-peer interactions [120]. Emmy said that she feels “lucky” that she works four days per week with a flexible schedule and can observe and prepare assessments and talk with staff during her working hours. Concerning staff transition, both teachers had to take sick leave for several months; the teaching assistants took the lead and helped the new teachers more. The new teachers arrived a few weeks before the children’s transitional stage and sat next to the teachers and teaching assistants to observe how the daily routines functioned. The supply teachers were selected because they had worked in this school previously and, therefore, were familiar with the system. Nursery staff elaborated a plan for transition, transition notes, and foundation stage reports for all children and reviewed the individual provision plan for the children with SEN.

At the nursery, staff ensured that individual follow-ups included all the children and that each of the staff had eight or nine key children. At the beginning of the year, the team met to read the children’s paperwork, determined which children they would have, and started performing case studies and taking notes accordingly. As the teaching assistants observed the children and how they interacted with other children, they also took note of their typical concentration spans and related some of their findings to the scale point system linked to the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) profile. According to the staff, the learning strategies were based on what they were learning from the children’s experiences. First, the transition programme helped them observe the child in their previous setting and learn from relationships and strategies. They later copied the previous strategies and techniques and adapted the activities to the new space. Each time they confronted a difficulty, they communicated with the expert in the area and with parents, visiting all their key children’s homes. Emmy highlighted how fast it was to evaluate children and their intervention from external services in this school, mainly due to alternative communication systems.

Regarding the two children identified with SEN, Alice and Anna identified their speech delay after one week in the nursery class. Only one week later, they started a five-week group session with the local authority’s speech therapist. Carolyn Webster-Stratton’s teacher programme from the Incredible Years series was selected to foster the ability to promote social, emotional, and language development of one of the children with SEN. For example, if they had not received the speech therapist’s resources during the last month, the teacher spoke to Emmy, and together they elaborated the pedagogical tools needed. Inclusion in this classroom is conceptualised by the common understanding of the staff and children’s roles as becoming the main actors. As confirmed by Kelly [121] this case study brought together the staff’s wisdom and capability, which took place in an environment where the staff were experiencing “good learning”. Explicit professional learning is shown in this case study [122], as it responded to challenging areas of teaching [123].

Nursery staff enjoy finding ideas and searching for new ones, echoing the idea by Eraut [60] that learning is researching. Therefore, they were proud to have created a small library in the corner of the first-aid room, a room with many academic books about education theory and practices for nursery level and information about curricula. The nursery staff requested the books for the school, and they were bought with materials-budget expenses allocated to class materials. In particular, the team took ideas from a Nursery World magazine. Anna said that the magazine was helpful, as “it writes about real-life things in real settings”. The staff sat around the small children’s table and read together during their break time. They reported that they “all loved reading it” together during these periods. They also shared that the kitchen space was small, they avoided the staff room, and they did not like to spend the time from their break talking to other school staff. They highlighted that they had expected the school to provide an area inside their nursery to relax and speak during breaks. The teaching assistants went outside to a local coffee shop during their breaks throughout the academic year. The two teachers stayed in the nursery class, eating a small salad or sandwich and planning. This specific structural issue created another loss of time and opportunity for collaboration.

4.4.2. Affinity with Sources of Opportunities for Professional Development through after-Work: Informal Learning

Nursery staff said that valuable professional activities are those informal learning strategies that were unofficial, casual, and unregulated; they took place outside the school through communities of learning such as internet forums [124], friends, other professionals, and their families. Emancipatory learning took place when the staff listened to the learning community outside their workplaces, and they acknowledged the need for more contact with like-minded individuals. Both the teachers and Emmy shared that they had expanded their knowledge with such colleagues, e.g., teacher friends whom they had met at the university. Some of those friends continued to work at the university, and they chatted about new research, offering new ideas, particularly about transitions with others that worked with secondary education children. Furthermore, Emmy recognised that she used an online self-help forum for SENCos to communicate with other people in similar settings. As her job was very demanding, she found this community to be of great support in having people to share experiences with others in the same situation. It was an excellent place to obtain advice from people who had experience with precisely the scenarios in which she sometimes needed extra guidance. The information that Emmy narrated supports a case study by Cook and Smith [125] on informal community e-learning [126]. Likewise, Anna mentioned an online training forum that helps teachers with SEN children. Teachers and SENCos also shared the habit of reading books about pedagogy that they obtained from the library. Specifically, teaching assistants talk about practical knowledge, saying that they learn a great deal by experimenting at home with their own children, meeting their friends (also TAs), and talking about activities.

5. Conclusions

This article has been developed from rich experiences in which we observed how staff were learning and how learning communities directly benefitted. This article specifically analyses, from inside the organisation, those factors that promote and challenge the professional development of all the participants working in a nursery classroom, particularly with a group of professionals who feel confident about their inclusive practices. In this regard, according to national statistics, they are among 20% of total EYFS staff who feel qualified.

This article introduces a unique setting in which the staff were receptive to describing how they work in a complex system in which they still face challenges but feel proud of how their efforts have been coordinated. Staff narrated the challenges of professional learning regarding their employment contracts and structural issues that differentiated them into the categories of teachers and teaching assistants. They felt that these issues created a power struggle that hindered their professional development. Participants highlighted the contradictions in their contractual recognition as professionals regarding the types of employment contracts they received, their professional identities [113] and their working hours.

Meanwhile, in the classroom, the participants were empowered and motivated and showed pride in creating a unique active learning environment. The staff had their own way of organising motivated dialogues among themselves and with the children, which benefitted their primary goal, that of the children’s well-being. The opportunities to meet and share were the key to the development of early years professionals. In this setting, participants learnt how to carry out tasks, lesson designs, and analysis to improve their development and are led toward those for which they are most suited [127] Organisational learning [128] was put into practice through the staff’s own continuous reflection on their increased understanding. This article explained facilitations networks structures developed by nursery staff, thus exemplifying their implementation of sources and strategies [129]. They implemented an active-learning culture in the classroom, in which all staff agreed on an approach that allowed them to learn from children’s achievements. Staff structured time and resources in their work schedule and actively applied policies that emphasised training, knowledge, activity implementation, and formative assessment evaluation review.

The results of this article concur with those of Robins and Silcock [130], who have identified that in nursery classes in primary schools, teaching assistants and nursery teachers could have complementary roles involving varied skills for resourcing, organising, and interacting with others. For example, if a TA is away on sick leave, another could join in and work at the same level without affecting the children’s learning processes. Many factors characterise the unique characteristics of this nursery setting; namely, staff shared the same goals and values toward inclusion and focused on creating clear policies and guidelines at the school and within the classroom, including personnel roles and expectations. A well-established community of learning was reinforced, including nearby schools and the following year’s school classes and professionals, in addition to parents and external professionals. Staff valued pedagogical resources and worked to obtain those needed to cater to the children’s needs. Staff experienced professional learning both inside and outside the school setting through non-formal learning inside the nursery room, and through informal learning during activities with their families. All staff were involved in planning and preparing future activities, such as reading ideas together in magazines. This English school setting relates to the culture of learning among teachers and assistants. The idea of “co-production essentially indicates that the educational environment needs to move towards treating everyone equally but not necessarily the same” [48]. In this scenario, teachers must continuously carry out their work by “balancing, monitoring and adjusting” to each student’s needs. This practice is vital as a framework for feedback [51]. Flexible practices can benefit all students, as group tutoring, individualised support in a mixed group, and personalised intervention allow them to share their potential throughout class activity [131] (p. 9). Continuous reflective and critical self-evaluations add value to improving practices and target equity and social justice [132]. Professionals acknowledge their role in helping children develop compensatory strategies and mediated learning [133].

Staff also pointed out that many valuable learning experiences take place outside the nursery, which the authors suggest should be considered by the school and administration. Indeed, the latter both agreed upon and valued a need for the recognition of learning outside the classroom. As challenges, staff specified the formal lack of recognition of prior knowledge and experiences, and not being offered a work-life balance nor recognition of work outside paying working hours.

This study serves to highlight exploitation within the education system, which cannot be ignored. The teachers in this case study observed that they had expected heavy workload. This indicates that it would be in early childhood staff’s own interests, including SENCos, to advocate the need for lifelong learning regarding the development of professional practice. As the authors appreciate the hard work of these professionals, we believe urgent changes are needed, and their working contracts must reflect the real working hours and extremely demanding duties all professionals carry out. As for the teachers in this case, their professional development learning experiences were not promoted and acknowledged by the broader system, and the professional learning community at the EYFS group failed to influence the structure of the organisation as much as the staff had expected. However, it was determined that allowing teachers the time and space to develop their profession while reflecting on their shared experiences and collaboration within the school environment improves their professional practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.-G.; methodology, A.C.-G.; software, A.M.M.-M.; validation, C.S.-M. and N.N.-G.; formal analysis, A.C.-G.; investigation, C.S.-M.; resources, A.M.M.-M.; data curation, C.S.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.-G.; writing—review and editing, A.M.M.-M.; visualization, A.M.M.-M.; supervision, N.N.-G.; project administration, A.C.-G.; funding acquisition, A.C.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was carried out following the rules of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 (https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/medical-ethics/declaration-of-helsinki/, accessed on 3 May 2023), revised in 2013. The research proposal was approved by the research ethics committee from Anglia Ruskin University. The protocol was approved by the Anglia Ruskin University (Approval Date: 10/05/2016) of the project named as “Title Research Project: The Implementation of inclusive practices in early childhood settings in England and Spain; an exploratory case study”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Teacher’s Previous Experiences and Previous Studies.

Table A1.

Teacher’s Previous Experiences and Previous Studies.

| PSEUDONYM: ALICE FUNCTION: “MAIN CLASS TEACHER A” (Deputy SENCO) AGE: Around 32 Years Old Two Interviews (October 2018 and June 2019) | |

|---|---|

| Previous Studies | She had a bachelor of arts with qualified teacher status and a summer scheme with autistic children. Twelve years of experience with children with ASD, ADHD, hearing impairments, EAL, visual impairments, and social and communication difficulties. She was a deputy SENCo doing a SENCo accreditation course by funding available from the school and was responsible, together with the SENCo, for drawing new targets for children with SEN in nursery. She worked as a school SENCo on Fridays. |

| Experience | She had worked in summer schemes with autistic children. She said that she learns a bit at the university and wherever we are demanding. The teacher training included differentiation and inclusion. “You get years of experience, then you start to pick out different things you go to courses and then you watch other people and a lot of new information, and further research comes in. You read it, and then you applied it”. “I got 18 A levels, then I went to the university for four years to do teacher training, and I earned a Bachelor of Education and history; this is the qualified teacher status. She is a qualified teacher from 3 to 11, and then she can teach from nursery right up to year 6. She has been to two other schools, but they have not had nursery classes in the other schools and had different age groups. “This is my fourth year in this nursery”. |

| PSEUDONYM: ANNA FUNCTION: “MAIN CLASS TEACHER B” Age: Around 50 Years Old 2 Interviews (October 2018 and June 2019) | |

| Previous Studies | Bachelor of Education Honours and 24 years of experience with children with autism, children with physical disabilities, visual impairments, hearing impairments, EAL, ADHD, and ASD. She did four years of study at the university, and as part of the course, she studied how children acquired speech and how language is brought up and how that it was a significant section of that and to understand where children are when they come into the school and if they do not speak, what are the possible causes. |

| Experience | She has been working in this service for around 20 years. Mainly in reception, this was her second year in nursery. About eight years ago, she had a little boy with severe autism and a little boy with psychical disabilities in the same class, and she felt that she was pretty unprepared to have both of them. They were only four at the time, and the little boy with physical disabilities had a lot of equipment. He can rotate that he could not move(?), so she made many changes for him, but in terms of the learning experience, they were both fine being in mainstream school. Another 20 years back, and they would not be in a mainstream school, they would not have been the right place for them, but that was a challenging year with both of them! Since then, she has had many children from the autism spectrum, seem incremental more and more now, and fewer children with physical disabilities, but many children have barriers in different ways. She thinks that she sees children with speech and language and delay more and more now, and they need, not particular input, but you have to think carefully about the way you explain activities and have the goal of understanding the other children. |

| PSEUDONYM: EMMY FUNCTION: SENCo Age: Approx. 60 Years Old Two Interviews (October 2018 and June 2019) | |

| Previous Studies | She was a class teacher, and she did an open university course because she felt she had to have more training, but that was not compulsory when she started. |

| Experience | She has taught in junior schools and with infants, so she had experience in all the primary range when she will left teaching when my daughter was born. She came back part-time, and that is when she started doing special needs work because there were children who needed extra support. During the years, the job has grown and grown until now that she works four days a week, and I have built up my expertise. She did an open university a short course on inclusion, and she attended lots of other courses, so she had got the knowledge of most difficulties. |

| PSEUDONYM: ELLEN FUNCTION: TEACHING ASSISTANT (a) Age: Around 28 Years Old (Part-Time Teaching Assistant) HOURS A WEEK: (32.5 h a Week) Two Interviews (October, 2018 and June 2019) | |

| Previous Studies And Experience | She went to school, and after she went to college and from college, she got my job straight here. She was 18 when she started here, and she has been here for ten years now. |

| PSEUDONYM: ANDREA FUNCTION: TEACHING ASSISTANT (b) AGE: Around 24 Years Old HOURS A WEEK: (30 h a Week) Two Interviews (October 2018 and June 2019) | |

| Previous Studies | She has received a degree, so it has all been about being inclusive. She has a bachelor in education in childhood studies. |

| EXPERIENCE | It has been a year and a half that she has been here, a year in the nursery, and a few months in reception. |

| PSEUDONYM: MARY FUNCTION: TEACHING ASSISTANT (c) (Part-Time in Nursery and Reception) AGE: Around 34 Years Old. WORKING HOURS: (13 h a Week) Two Interviews (October 2018 and June 2019) | |

| Previous Studies | College for further education to be a nursery nurse, from 16 (the soonest you can leave the school) and she left it when she was 18, and she went straight to the job. The course she did took her around two years to do in which she had to do a lot of coursework, observations, planning, and she used to do a set amount of days in college and a set amount of days in school and in the nursery and some training in a hospital as well. |

| Experience | She had 16 years of experience. She has been working in nurseries, in people’s homes as a nanny, and schools playgroups. She has only been working in the nursery since this September. She has been working with children from anything from birth to eight years. |

| PSEUDONYM: DORY FUNCTION: TEACHING ASSISTANT (d) AGE: Around 35 Years Old WORKING HOURS (19.5 h a Week) Three Interviews (November, April, and May) | |

| Previous Studies | She has always been a nursery nurse, she went to college for two years, and she had her diploma from the college, and there were always ongoing training and courses. |

| Experience | A part of the training working in a special needs school and I she thought that was something that she wanted to do… but when she was there, she thought that this wasn’t for her. So she have been in this school for 17 years, and before that, she was in a private day nursery for two years. |

Appendix B. Interview Guide

| What is Inclusion? |

|---|

| Could you please describe what is learning at school? How do you learn about inclusion? Could you please describe what happens when you are learning, in your own words? What do you do when you are learning? How do you feel when you learning? Prompt: physically, emotionally, mentally. Identity and roles Describe your background on working with children with SEN or disabilities? How could you describe yourself as an individual that include all children in the class? Working here made you a difference on how you work as teacher? What about compared to before working here? |

What does the term professional development mean to you? How do you define it?

How do you keep up to date with learning trends?

On a day-to-day basis, how do you deal with working with children with SEN? Ways of cooperating, practical.

How do you feel?

Appendix C

Figure A1.

School Historical Progress into the Inclusion of Children with SEN.

Figure A1.

School Historical Progress into the Inclusion of Children with SEN.

References

- UNESCO. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. In Treaty Series; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006; Volume 2515. [Google Scholar]

- Warnock, M. Children with special needs: The Warnock Report. Br. Med. J. 1979, 1, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadwell, M.R.; Roberts, A.M.; Daro, A.M. Ready to teach all children? Unpacking early childhood educators’ feelings of preparedness for working with children with disabilities. Early Educ. Dev. 2020, 31, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, M.; Wong, G.T.; Fleming, C.M.; Garvis, S. Is Teacher Qualification Associated with the Quality of the Early Childhood Education and Care Environment? A Meta-Analytic Review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2019, 89, 370–415. [Google Scholar]

- Nutbrown, C.; Clough, P.; Atherton, F. Inclusion in the Early Years; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.-H.; Dimitrov, D.M.; Park, D.-Y. Effects of Background Variables of Early Childhood Teachers on Their Concerns about Inclusion: The Mediation Role of Confidence in Teaching. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2018, 32, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pit-ten Cate, I.M.; Markova, M.; Krischler, M.; Krolak-Schwerdt, S. Promoting Inclusive Education: The Role of Teachers’ Competence and Attitudes. Insights Learn. Disabil. 2018, 15, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Borkett, P. Special Educational Needs in the Early Years: A Guide to Inclusive Practice; SAGE: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J.D.; Garner, P.; Lee, J. Managing Special Needs in Mainstream Schools: The Role of the SENCo; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Nurse, A.D. The New Early Years Professionals Dilemmas and Debates; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Peleman, B.; Lazzari, A.; Budginaitė, I.; Siarova, H.; Hauari, H.; Peeters, J.; Cameron, C. Continuous Professional Development and ECEC Quality: Findings from a European Systematic Literature Review. Eur. J. Educ. 2018, 53, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K.; Meredith, C.; Packer, T.; Kyndt, E. Teacher Communities as a Context for Professional Development: A Systematic Review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 61, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonsén, E.; Soukainen, U. Sustainable Pedagogical Leadership in Finnish Early Childhood Education (ECE): An Evaluation by ECE Professionals. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 48, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisham-Brown, J.; Hemmeter, M.L.; Pretti-Frontczak, K. Blended Practices for Teaching Young Children in Inclusive Settings; Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, S.M.; Edwards, C.P.; Marvin, C.A.; Knoche, L.L. Professional Development in Early Childhood Programs: Process Issues and Research Needs. Early Educ. Dev. 2009, 20, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukkink, R.G.; Van Verseveld, M. Inclusive early childhood education and care: A longitudinal study into the growth of interprofessional collaboration. J. Interprof. Care 2020, 34, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.; Iannone, R.L. Innovative approaches to continuous professional development (CPD) in early childhood education and care (ECEC) in Europe: Findings from a comparative review. Eur. J. Educ. 2018, 53, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, J.; Sharmahd, N.; Budginaite, I. Early childhood education and care (ECEC) assistants in Europe: Pathways towards continuous professional development (CPD) and qualification. Eur. J. Educ. 2018, 53, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, R. Belonging in an age of exclusion. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. Teacher collaboration: 30 years of research on its nature, forms, limitations and effects. Teach. Teach. 2019, 25, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrique, A.L.; Dirani, E.A.; Frere, A.F.; Moreira, G.E.; Arezes, P.M. Teachers’ perceptions on inclusion in basic school. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2019, 33, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, J.; Massing, C.; O’Keefe, A.R. Innovative professional learning in early childhood education and care: Inspiring hope and action. J. Child. Stud. 2019, 44, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodcock, S.; Woolfson, L.M. Are leaders leading the way with inclusion? Teachers’ perceptions of systemic support and barriers towards inclusion. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 93, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]