Abstract

This paper presents a case study of a decade-long technology-enabled teacher professional development (TPD) initiative for government-run school teachers in India. The TPD aimed at capacitating teachers in integrating project-based or constructivist learning with technology in curriculum and pedagogy. Teachers are central to the teaching–learning processes, and hence capacitating them to leverage digital technologies confidently is essential to improve the quality of education imparted to learners. This paper focuses on the use of innovative technologies leading to the education of teachers. A decade of TPD is divided into three phases providing an analytical framework for the evolving technologies and pedagogies across the phases. Documents, resources and tools used for the TPD activities, researchers’ first-hand experiences and documented research studies supported the comparative analysis of the three phases of TPD. This comparison highlighted leading-edge technologies influencing changes in TPD delivery mode, learning support, pedagogy, scale, etc., across the phases. The paper also maps the interrelationship between technologies and pedagogies of TPD, suggesting various features of innovations such as continuous, practice-based, collaborative, scalable, shareable, transferable, and adaptable.

1. Introduction

In India, the debates on technology integration in education have changed from yes-or-no technology to what are meaningful ways of integrating technologies in education [1]. The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly played an important role in changing the discourse on technology in education [2]. This paper draws on the teachers’ professional development (TPD) process, which was part of a decade-long field-based initiative called the Integrated approach to Technology in Education (ITE) [3]. ITE was based on project-based learning with technology (PBLT) for teachers in secondary (grades 5 to 10) government schools in India. This implementation, present since 2012, required teachers to design activities within their curriculum that allowed students to create learning artefacts or projects using technology. Robust TPD was required in order for teachers from rural government schools to design, implement, appreciate, and sustain the approach of PBLT/ITE in their curriculum and pedagogy.

The government-run schools in India follow a standard curriculum prescribed by the state, which ties to the larger National Curriculum Framework of India [4]. These state-run schools provide free education under the Right to Education Act 2009 [5], and primarily children (65%) from lower socio-economic families attend these schools [6].

In the lower socio-economic educational settings of Indian society, technology integration issues are still around infrastructure access, with now more focus on accessing digital content and resources [7]. The Indian National Education Policy 2020, for the very first time, focused on education technology beyond the scope of digital literacy and infrastructure support [8]. It emphasised the effective and innovative use of technology in improving teaching and learning for the continuous professional development (CPD) of teachers and the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies for scaling best practices and assessments.

2. What Is Innovative Use of Technology in TPD?

Challenges related to infrastructural access and connectivity have been at the forefront of research related to teaching and learning with technology in lower socio-economic settings. However, studies have also shown that at-risk children best learn with technology if it is used for improving interaction, to research and create with technology, and if it does not replace teachers [9].

Best practices in education technology used in K-12 education have been researched extensively in the past. For example, Kozma’s international study in 28 countries clearly indicated that innovative use of technology across countries was connected to the curriculum; teachers used it to alter their pedagogy and roles as facilitators and fostered collaboration, research, and creation of products by students [10].

The developmentally appropriate technology in early childhood (DATEC) model [11] for effective use of technology also indicated that meaningful technology would integrate with the curriculum, put children in the central role, and support them for play and collaboration.

Overall, effective technology is said to be one which is easily integrated into regular classroom teaching, curriculum, and pedagogy without asking for major changes or disruptions in the teaching and learning routine [12].

Besides the term best practices, literature also uses the terms innovative technologies and leading-edge technologies in education. For example, Rosas et al. [12], Wilson [13], McDowell [14], and Davidson [15], in their studies, have defined leading-edge technologies in online education to include the use of a variety of devices and applications with user autonomy and fostering communication and collaboration in online learning.

Besides literature on best practices and innovative technologies for learners, many researchers have documented best practices in teacher professional development (TPD) and the role of technology in supporting the same. Teachers need to play an active role in preparing schools to integrate technology effectively by designing and implementing 21st century pedagogy in the curriculum [16]. International Standards of Technology Education (ISTE) for teachers insist that teachers’ learning and leveraging newer technologies to enhance students’ learning be a continuous practice. ISTE proposed that teachers engage and collaborate with their learners and other teachers to design authentic learner-driven activities [17].

Darling-Hammond and colleagues [9] have laid down seven elements of an effective TPD program, which include a focus on content involving active learning strategies, allowing opportunities for collaboration, modelling new strategies, providing coaching and expert support, including opportunities for feedback and reflection and sustained duration. A study by Crandall highlights that it is not just TPD but the experience of successful implementation that can change the perception of teachers [18]. Technology-supported TPD can provide continuous and immediate learning support to teachers [19]. The TPD discussed in this paper centred around building the capacities of teachers and educating them on integrating technologies in education. Previous research has mentioned that teachers require substantial and ongoing professional development to build appropriate pedagogic practices for using ICT tools effectively [20].

This paper focuses on the leading-edge use of technologies supporting innovative features of TPD for educating teachers in the constructivist use of technologies in their classrooms. These innovative features will be drawn from the context of a large TPD program for in-service teachers conducted in three phases situated within the ITE approach. The three phases of TPD are described in the subsequent sections.

Phase 1 (2012–2016) TPD used a workshop approach to orient teachers on the concepts related to learning, project-based learning (PBL), 21st century skills [21], the technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge (TPACK) model [22], and the role of technology in pedagogy. The teachers would then design lesson plans based on project-based learning with technology (PBLT) and create projects as if they were students. In this phase, the teachers in TPD were from ITE implementing non-government organisations (NGO) and later included teachers from government schools.

Phase 2 (2017–2018) of the TPD moved from workshops to a 16 weeks certificate course accredited by a university, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. In this phase, the curriculum and pedagogy of Phase 1 were further developed to integrate academic readings, assessments, and technology platforms and tools. The mode of TPD was blended that included four days of workshops followed by a distance period enabled by technologies to support teachers in practising PBLT with their students. Another practice component was added to this distance period, where teachers had to orient on PBLT through face-to-face (F2F) workshops with about 15 to 20 other teachers in their school or neighbouring schools. State/district government bodies were administrative partners in this process. While this course was largely offered to government school teachers in middle and secondary schools from ITE implementing geographies, it also included teachers and coordinators from ITE implementing NGOs who were interested in academic credentials.

Phase 3 (2019–2022) of the TPD was built further on the curriculum and pedagogy of the earlier phase to offer TPD in a completely online mode. Multiple technologies were harnessed in this phase to provide learning support for teachers to understand concepts and processes and practice their new knowledge and competence in a real classroom and training context. The certificate course was further split into two courses, Part 1 and Part 2, and then into micro-courses for digital badges during the COVID-19 lockdown period (CLP). This phase scaled beyond the ITE geographies and extended to other states (Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Jharkhand, and Jammu and Kashmir). However, the main learners continued to be government-run school teachers, including teacher educators from their respective states.

The following sections present a comparative analysis of the three professional development phases.

3. Research Method

This paper uses a case study approach comparing TPD over a period of ten years within the ITE initiative. Yin defines a case as “a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context. Case studies can offer purposive, situational or interrelated descriptions of the phenomenon, connecting practical complex events to theoretical abstractions” [23].

Here are the documents that served as important data to dive deeper and compare the three phases of the TPD:

- Phase 1: Presentations used during the F2F workshops.

- Phase 2: Certificate course reports, pre- and post-course survey data analysis presented in ITE ‘Learning & Results’ report created by an internal team, external review report of the ITE program, and digital portfolios submitted by course participants.

- Phase 3: Course storyboards for authoring on the Learning Management System (LMS), which included assignments, readings, multimedia content, discussion forums, etc.

Besides documents, research studies conducted within the ITE context were used to draw relevant results and analyses for this paper. Research studies on Phase 2 participants were used: the relationship between teachers’ participation in community of practice groups and their performance in the course [24,25], transference of PBLT in classrooms [26] and CLP [27]. Further, data analysis from teacher interviews documented in the digital badge course project report [28] and conference papers [29] were used for analysing Phase 3.

Three of the authors of this article were directly part of the design and implementation of the TPD program, and one of the authors is the founder of the ITE program in which the TPD program has been situated. These three authors’ experiences have shaped the access and interpretation of the documents used in this study. Thus, the self-study method was used, which is a methodology of inquiry where the researcher, as a practitioner, mostly a teacher educator study, reflects on one’s practice. The researcher in self-study draws upon methods including case studies employing different sources of data such as interviews, teaching or training artefacts, reports, photographs, etc. [30].

4. Comparative Analysis of Three Phases of TPD

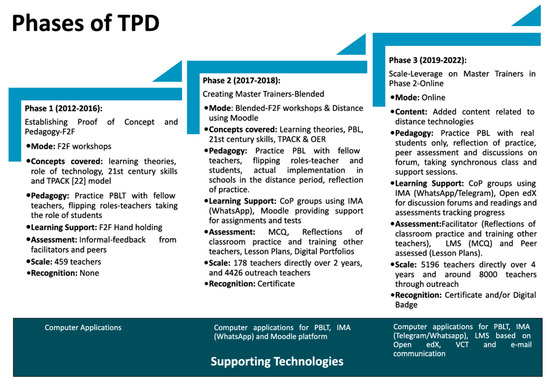

Guided by the three modes of TPD delivery, the TPD activities, documents or artefacts were mapped to the three phases: face-to-face (F2F), blended, and online modes. This initial mapping resulted in identifying the common components of TPD across phases: duration, concepts covered, pedagogy, learning support for teachers, assessment, scale achieved, and type of recognition. A set of leading-edge technologies supporting these components across phases were identified and illustrated.

The following section presents a comparative analysis of the TPD components identified and their supporting technologies in each of the three phases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparing three Phases of TPD.

4.1. Phase 1: 2012 to 2016

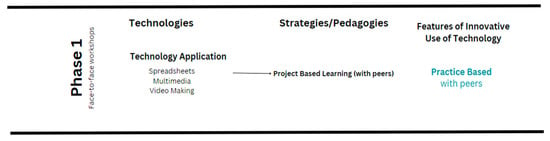

Phase 1, being largely F2F, the teachers used basic computer applications to practice PBLT, which characterised TPD as practice-based (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Phase 1 Features of Innovation.

4.1.1. Mode: F2F Workshops

The TPD in this phase used rigorous face-to-face (F2F) workshops conducted over three to four days with teachers at NGO learning centres and (later) rural government schools.

4.1.2. Concepts Covered: Learning Theories, Role of Technology, 21st Century Skills [21], and the TPACK [22] Model

The ITE model was used as a central approach in these workshops advocating project-based learning (PBL) with technology (PBLT), where students would create learning artefacts or projects using technology and teachers would design learning activities, thus, fostering 21st century skills [21], agency to design and create with multiple tools and resources, and connecting with curriculum goals. There were no readings provided on these topics.

4.1.3. Pedagogy: Practice PBLT with Fellow Teachers, Flipping Roles—Teachers Taking the Role of Students

The workshop offered hands-on practice, such as designing technology-enabled learning activities and creating projects (imagining themselves as students) using technology applications with peer teachers. Since Phase 1 of the TPD was based on individual workshops, there was no systematic or individual follow-up of teachers practising PBLT with their students in the classroom.

4.1.4. Learning Support: F2F Handholding

During the workshops: Most of the teachers made their lesson plans on paper and then gradually started using spreadsheets, the internet, video-making software, etc., to make projects based on the lesson plans. The facilitators supported the teachers in making lesson plans and projects.

Between the workshops: Some refresher training or visits by the ITE lead were made to provide feedback in limited field areas. ITE facilitators from NGOs did handhold some of the teachers in the field to practice PBLT. While IMAs and video conferencing applications were still emerging in 2013–2014, the NGO ITE facilitators collected some sample lesson plans and projects made by students and shared with the ITE lead via e-mails and gained feedback over telephone calls. However, these communication technologies were not directly used by the teachers.

4.1.5. Assessment: Informal Feedback from Facilitators and Peers

The facilitators of the workshops gave feedback on lesson plans made by the teachers, and in groups, teachers sought feedback from peers on the projects that they made imagining themselves as students. Teachers used technology applications for making projects, and the ITE project rubric [31] was used to assess/grade the projects by their peers, thus modelling the real classroom context.

4.1.6. Recognition

No formal recognition was provided to teachers in this phase.

4.1.7. Scale: 459 Teachers

The ITE lead trained teachers and NGO facilitators directly; subsequently, one or two NGO facilitators started training other teachers in their states. A total of 459 teachers were trained in this phase.

4.1.8. Relevance of Phase 1

The aim of Phase 1 of TPD was to introduce student-centred use of technology in the form of PBLT within the school subjects. These concepts were new for the teachers as the integration of computers in subjects during this time was largely focused on drill and practice, especially in the government and other schools and centres where students came from underprivileged settings. The concept of using technology in the form of project-based learning within subjects was itself a leading edge, as the use of computers was mostly seen as a standalone subject to be used in computer laboratory settings.

The nature of TPD was largely F2F, in the form of workshops followed by handholding support to a few teachers in the field and feedback through e-mails and telephone calls through NGO partners. Since this was stage 1 of the intervention, establishing proof of concept in small geography was more important than scaling it.

4.2. Phase 2: 2017 to 2019

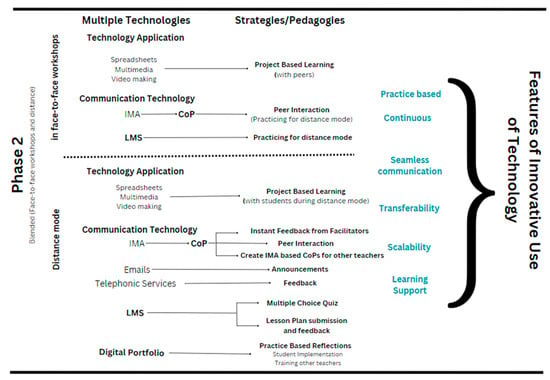

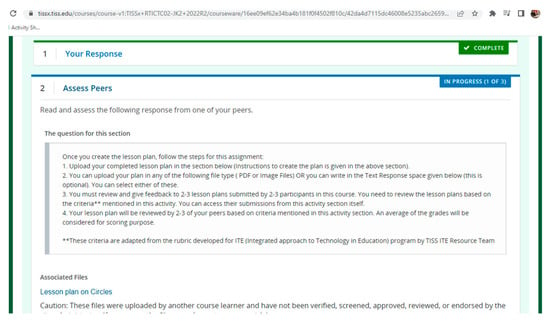

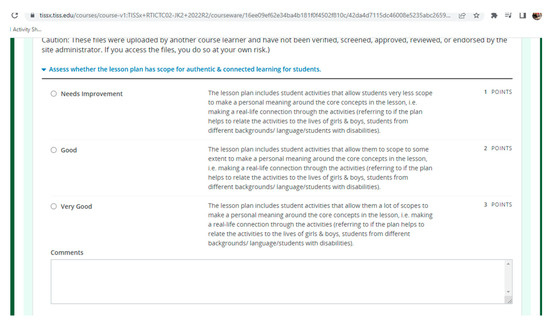

Phase 2 TPD moved from a workshop to a certificate course form. Besides basic computer applications to practice PBLT, Phase 2 harnessed two distance technologies: an instant messaging application—WhatsApp and a learning management system—Moodle. These technologies supported various pedagogies and contributed to many features of innovations, such as continuity, scalability, and recognition (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phase 2 Features of Innovation.

4.2.1. Mode: Blended

Here the TPD was a blend of F2F workshops followed by distance period engagement covering reading and practice assignments using asynchronous technologies (learning management system and instant messaging application).

4.2.2. Concepts Covered: Learning Theories, PBL, 21st Century Skills, TPACK, and Open Educational Resources (OER)

The course started with four days of F2F workshops covering the concepts from the first phase and adding concepts such as authentic learning, International Standards in Technology in Education (ISTE), OER, etc. Discussions in the workshop also included topics on ethical considerations regarding the use of technology, internet safety, the digital divide and challenges of implementation. Unlike Phase 1, Phase 2 provided digital copies of readings of articles from original and prominent authors and organisations, such as works by Chris Dede, comparative frameworks of 21st century skills, the ISTE website, State ICT guidelines, etc. Most of these were in the English language, but during F2F workshops, teachers were supported in local languages to make sense of these readings. Certain assignments around these readings were scheduled in the distance period. Since teachers were not used to reading such literature, these readings were summarised in simple words with ample examples from the field. The workshop model of Phase 1 largely included NGO facilitators rather than school teachers, was short without planned continuity and did not include academic credentials like in Phase 2. Thus, it was difficult to present readings from the literature in Phase 1, which would require time for the teachers to practice, reflect, and relate the readings with their own classroom context.

4.2.3. Pedagogy: Practice PBL with Fellow Teachers, Flipping Roles—Teacher and Students, Actual Implementation in Schools in the Distance Period, Reflection of Practice

Similar to Phase 1, in the Phase 2 workshop, the teacher participants were provided opportunities to design lesson plans integrating PBLT and implement the same with colleagues (acting as students—micro-teaching). Reading and discussion of articles and websites as resources were added as newer pedagogies. Additionally, towards the end of the workshop, the teachers were asked to create district-wise groups and develop plans for orienting other fellow teachers on the concepts they learned during the workshop. These four days were quite rigorous and created a strong bond between facilitators and teacher participants. This rapport was quite useful in keeping teachers motivated and sustaining their engagement throughout the course in the distance mode in the subsequent weeks.

The distance period of TPD in this phase integrated teachers’ practice of their PBLT-enabled lesson plans with real students. It gave them time to reflect on the concepts learned in the F2F workshop and revise their lesson plans or make new ones more appropriate for implementation in a real classroom environment within its challenges. Thus, distance technologies allowed the authentic practice of concepts experienced in the workshop. The distance period also offered them an opportunity to transfer their learning to other teachers by conducting two to three days of F2F workshops in their districts.

4.2.4. Learning Support: Through IMA WhatsApp and Moodle Platform

The F2F workshops had rigorous support from facilitators in understanding key concepts and practice of PBL with different technologies. The distance mode period required seamless communication between the course facilitators and teacher participants. Since many teacher participants were familiar with or already using WhatsApp, this IMA was selected to form a practice or CoP group. These groups were used to stay in touch with each other, share experiences of classroom practice and clarify doubts about readings and assignments in the distance mode. The Moodle course management platform was used for submitting assignments, accessing readings, and taking tests. This blend of F2F and distance technologies allowed teacher participants the opportunity for continuous engagement for 16 weeks.

Consistent with the characteristics of effective TPD stated in the literature, the CoP of Phase 2, using IMA facilitated instant communication and collaboration among peers and course facilitators at scale [32], provided a platform for the teacher participants to seek help, shared achievements using text as well as multimedia format [33]. Certain communication on IMA enabled CoP groups to replace formal communication formats such as e-mails and letters among the state and university coordinates, which reduced time for communication and subsequent actions [33].

4.2.5. Assessment: Facilitator (Lesson Plans, Reflections of Classroom Practice, and Training Other Teachers) and LMS (MCQ) Assessed

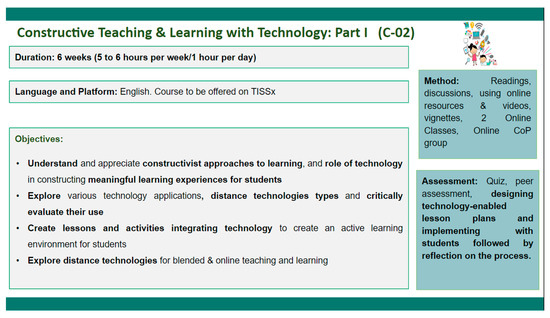

The assessment of the course varied from multiple choice questions, designing and implementing lesson plans in classrooms, reflecting on the implementation or practice in the form of a write-up or essay and creating a digital portfolio. The Moodle platform (Appendix A Figure A1 was used to systematically track the teachers’ assignment submissions and administer multiple choice questions ‘(MCQs)’.

Multiple choice tests in the distance mode led teachers to read resources (summarised readings of original authors) shared on WhatsApp groups and Moodle that reiterated concepts discussed in the workshop. Lesson plans made during the workshop were refined in the distance period based on the feasibility of implementation in their classrooms. After implementing their lesson plans and submitting reflections on their experience, the teachers moved on to another important component of the course assessment during the last two weeks of the course. Here, they were assessed on how well they could train or orient other fellow teachers in the neighbourhood schools. This activity for many teachers initiated their journey as mentors. The final assignment was creating a digital portfolio, a summative reflection of the teachers’ learning in the course. The teachers used various multimedia, including video-making software, to consolidate and present their overall learning and experiences in the course.

4.2.6. Recognition

Certificates from TISS, an academic institution, recognised teachers’ fulfilment of the learning objectives of the course. These certificates were distributed in a ceremony in the presence of the state government and the TISS leadership.

4.2.7. Scale

One hundred and seventy-eight teachers completed the certificate course in this phase and trained 4456 teachers in PBLT as a partial requirement of completing the course.

4.2.8. Summary of Analysis from Studies Conducted on Phase 2 Data

The distance technology platforms and tools (Moodle and WhatsApp) used in this phase offered constant learning support and feedback from course facilitators. This enabled teachers to stay engaged in the course, practice and reflect on their learning in real classroom settings. The following are the two studies conducted in the year 2020 to understand the relationship between teachers’ participation in a community of practice (CoP) enabled by WhatsApp and their success in the course.

Study on the relationship of engagement in CoP with success in the course: A study was conducted in the year 2020 [25] to understand the relationship between the level of participation of the teachers in the CoP and their performance in the course. Two of the CoP groups using WhatsApp in the Indian states of Assam and West Bengal were used for this study. These WhatsApp groups were established during the certificate courses in the year 2017–2018 for teacher participants, teacher educators, including one or two government officials, and the ITE supporting team. Teachers had spent about two years on their respective WhatsApp groups, extending beyond the certificate course duration. The West Bengal group had 43 participants, including 25 teachers, and the Assam group had 55 participants, including 27 teachers.

The conversation from these two groups was exported in text format for analysis in the year 2019–2020. Each message in the conversation consisted of fields such as time-stamps, the sender’s name/telephone number, the body of the message, and an indicator for media files. Using this structure, a browser-based tool was developed, which rendered the analytics of the chats [25]. The tool provided descriptive information on the number of messages sent by a user and other data for a deeper analysis. The number of messages and media files sent by a user was found from the frequency of occurrence of usernames. Based on this analysis, the ‘CoP heroes’ were identified as participants with the maximum number of posts. One of the common characteristics identified of CoP heroes was associated with their performance in the course; these participants completed the course with higher grades (A− or A+).

Similar findings were observed in the second study that was conducted in the year 2021 [34] in Phase 3 of a Telegram (IMA) conversation data from a newer cohort of teachers who took digital badge courses (micro-courses of the earlier four-credit course) in Assam. This cohort took the micro-course during the COVID-19 lockdown period (CLP). Since this study aimed to analyse communication patterns, a different method than the previous years’ study was used to analyse the data. The conversation was converted into a sociogram network in which each sender was represented as a node, and the messages exchanged between two nodes represented links between the respective senders (through replies). The senders with the highest number of links associated with their respective nodes were found to be the participants with higher grades in the courses. A cautionary note for both these studies was that the language of communication analysed on CoPs was English. The messages in regional languages could not be analysed because of Unicode incompatibility issues with the tools used for the analysis.

Studies on sustainability and transference of PBLT pedagogy in classrooms and newer contexts: A total of 19 teachers (who were trained by master trainers) and 15 master trainers (who took the certificate course) who were involved in the TPD Phase 2 were interviewed after 3 to 6 months of them completing the certificate course. Some of the study findings revealed that many teachers and master trainers indicated that the pedagogy of PBLT that they learned in the course sustained beyond the course in their classroom practice. Some teachers also used PBL in non-technology-enabled classrooms. Many teachers also indicated that the quality of their lesson plans improved and became more student-centric [27]. Another study with the teachers who went through this phase of TPD revealed that these teachers who completed the blended courses (Phase 2) were able to adapt to CLP better by using different technologies, including PBLT [7]. Both these studies also indicate transference of learning of the Phase 2 TPD in other contexts (classroom without technology and CLP), which is also referred to as an indicator of sustainability [35].

Besides a change in pedagogy for individual teachers, this phase of TPD also witnessed some systemic integration signalling long-term sustainability. For example, the F2F workshops and graduation ceremonies of certificate-completing teachers were integrated into state budgets for training, teacher participation in the course received official support through permission letters through state education departments, and state officials participated in the course activities and its planning. Figure 3 captures the innovative features of Phase 2 and its corresponding pedagogies led by multiple technologies.

4.3. Phase 3: 2019 to 2022

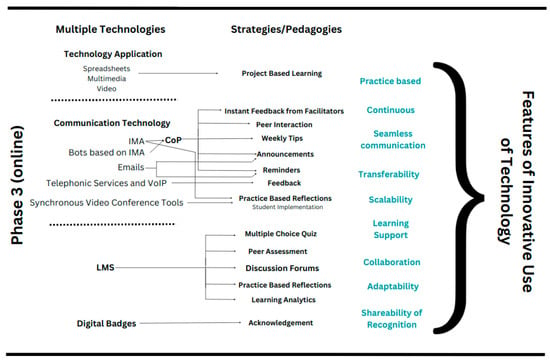

Phase 3 built on the prior phases that established proof of concept for constructivist teaching and learning with technology, practice-based pedagogies for TPD, and offering TPD within the academic milieu. In Phase 3, LMS based on Open edX supported multiple pedagogies and assessments and video-conferencing applications, making Phase 3 online, more adaptable and scalable (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Phase 3 Features of Innovation.

4.3.1. Mode: Online

In this phase, the course moved completely online with an aim to reach more teachers across the country. There were three forms of online implementation in Phase 3. The first form in the year 2019 was a small pilot with 10 and then with about 800 teachers in the CLP in the year 2020. This initial form had self-nominated teachers across the country, and the type of schools was mostly private. The second form of Phase 3 implementation was three digital badges. These three micro-course badges were a split of the online course, offered to about 600 teachers nominated by the states of Assam and West Bengal in the CLP in the year 2021. The third form of implementation was towards the end of the CLP in the year 2022, with support and funding from UNICEF, India This form of the online certificate course spread to about 3700 teachers (self- or state-nominated) and educators in 6 languages. Besides moving to completely online mode, the certificate course went through many structural changes.

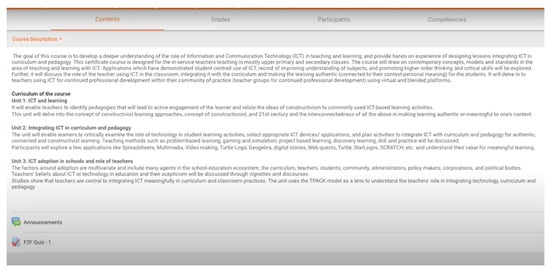

Change in course name and structure: The course name changed in the year 2020; the earlier four-credit course was split into two two-credit courses (each to be run for 6 weeks) and was named ‘Constructive Teaching and Learning with Technology’ Part 1 and Part 2. Part 1 covered all the major concepts and designing and implementing of lesson plans (Appendix A Figure A2). Part 2 aimed to prepare the learners as mentors to other teachers, requiring them to orient other teachers in the constructivist use of technology. The name change was required with the changing nature of technology and different terminologies in the area over the years. Technology and its enabled pedagogies in education were no longer restricted to information and communication. The words ICT and education also reminded us of the old scheme in Indian schools that looked at supporting computer desktops and basic skills in designated computer laboratories in schools. Since the course was focusing on constructivist learning harnessing the technology of different kinds, it was deemed appropriate to change its name.

Relevance of this course in CLP: Many other online courses for teachers offered at the same time focused on training in distance technologies and the creation of content for dissemination. These kinds of courses that focused on digital skills and access to content in CLP seemed more relevant than offering a course of constructivist teaching and learning with technology. However, at the same time, research on the CLP in the Indian context revealed that teachers were not only underprepared but also not very confident in using distance technologies and were reluctant to use the standardised online content, which was not relevant to their students’ context [29,36]. Most of these reports highlighted infrastructure challenges with students that kept them isolated from learning in distance mode [36,37]. Teachers who could use technologies used it mostly to give lectures and disseminate information and content in WhatsApp groups [29,38,39]. A small research project was undertaken in the year 2021 that was based on the second phase of TPD and teachers and their preparedness to use distance technologies and PBLT in the CLP [7,27]. The results of this study, as discussed earlier, provided more confidence to the Phase 3 team in offering the course on CTLT.

4.3.2. Content: Similar to Phase 2 with Addition Related to Distance Technologies

The content and readings in the course remained significantly the same from Phase 2; a few examples and assessment questions were added or modified. Some more content and units were added. For example, a framework of student-centred use of technology was added, characterising passive, active, (students) create, and communication (PACC) [3] use of technologies. This framework is intended to provide a critical lens to teachers for choosing different technologies based on the type of student learning, subjects, and teaching pedagogies they wish to design and implement. An additional unit was added to the course as it was deemed relevant given the CLP context in Phase 3. This unit covered types and uses of distance technologies and their tools and strategies to use it for active learning, with inquiry and PBLT in synchronous and asynchronous modes.

4.3.3. Pedagogy: Practice PBLT with Real Students Only, Reflection on Practice, Peer Assessment and Discussions on Forum, Taking Synchronous Classes and Support Sessions

F2F activities in the workshop were replaced by asynchronous activities on the TISSx LMS, synchronous classrooms, and self-paced practice in classrooms. Activities on TISSx required re-designing and enriching many activities and resources with multimedia to sustain the interests of the teachers in the asynchronous online mode.

The practice of creating student projects with peers in Phase 1 and Phase 2 workshops did not stand as meaningful in Phase 3 online mode and was discontinued. On the other hand, similar to Phase 2, the practice component of the implementation of PBLT in real classrooms and reflection of concepts learned in the course continued in Phase 3. The opportunity for the teachers to transfer their learning to other teachers by conducting two to three days of workshops in their districts also continued in Phase 3. However, the teachers were allowed to choose the mode of these workshops (F2F, blended, or online).

4.3.4. Learning Support: Through IMA—Telegram/WhatsApp, LMS Based on Open edX, and E-Mail Communication

Moodle, which was used in Phase 2, was discontinued, and an LMS built on Open edX called TISSx (http://www.tissx.tiss.edu, accessed on 11 January 2023) was used instead. TISSx was built at the Centre of Excellence in Teacher Education (CETE), Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), to design and offer many other courses at a reasonable scale. It used the Open edX platform, which was suggested by the MIT Open Learning office. Both these entities had a partnership for a larger education technology project in India. This change emerged as a promising alternative to pre-existing Moodle version, offering improved browsing and mobile application.

Over time, TISSx evolved to reach learners in a wide range of settings in multiple languages to be accessed through a range of devices: desktops, laptops, tablets, and mobile telephones. Since many teachers preferred accessing the course from their smartphones, TISSx was adapted to be also used on mobile devices and was made available for download from the Google Play Store. To maintain the interactive component of the course, instructions and questions for discussion forums and reflective essays were rephrased to improve clarity. The nature of multiple choice questions (hypothetical practice-based scenarios) was retained with some modifications.

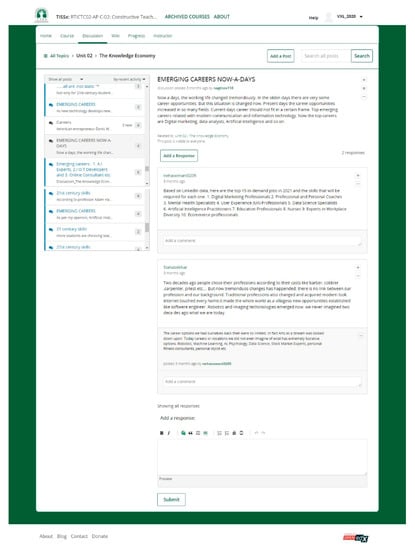

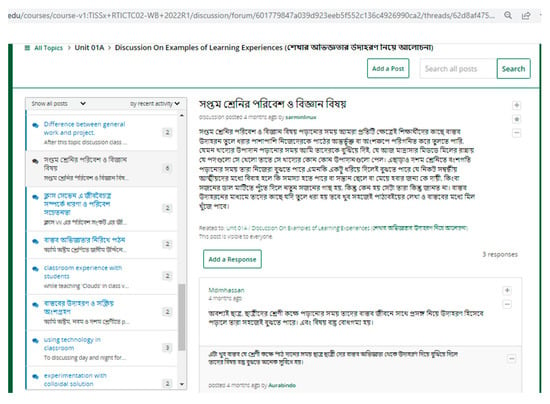

Since Phase 2 relied heavily on F2F workshops for discussions, clarifying doubts, and building a community, the LMS in Phase 2, Moodle, was under-explored. It was limited to submitting assignments, accessing readings, and taking MCQ tests. On the other hand, in totally online mode in Phase 3, the technology affordances of TISSx were utilised to support collaborations, discussions, and feedback for teachers. Tools such as discussion forums (Appendix A Figure A3 and Figure A4), peer assessment, and learner analytics allowing teachers to track their progress components on TISSx were utilised.

Synchronous Video Conferencing tool (VCT): The online class using a VCT was added in this phase. These online classrooms happened on multiple occasions in the form of the orientation of the course and expectations setting, presenting concepts in the course and clearing doubts by course faculty. VCT was also used for short helpline sessions on a regular basis by course facilitators.

Change in IMA for CoPs: The CoP groups were moved from WhatsApp to Telegram largely because of the following reasons: Telegram allowed larger groups and protected telephone numbers of the participants and facilitators; it allowed the possibility to explore the integration of a bot to automate some communication and analysis in the CoP group. However, to stay consistent with an IMA already familiar with the teachers, some of the state governments did not allow CoP groups on any IMA other than WhatsApp.

Besides learning support from facilitators, the teachers received learning support through peer mentors. These peer mentors were identified towards the 5th or 6th week of the course, were early completers of the course, and were approached to mentor other teachers. A separate CoP group using IMA was created by the course facilitators to communicate and plan strategies with peer mentors.

Bots in IMA: The process of designing and planting a bot in teacher participants’ Telegram groups was explored in one of the course instances. It was realised that despite an online orientation on the registration process and pinning/attaching the video of the registration process in the Telegram group, the teachers, especially those who missed the orientation or who were new to online learning and the TISSx platform, were struggling to register on TISSx. The course team had to respond repeatedly to similar queries, which was quite overwhelming for the team. At this time, a “Welcome Bot” was created, which was programmed to give a personal touch by posting a welcome message for each new participant who joined the Telegram group directing them to the video on the registration process. However, the subsequent course instances opted for WhatsApp as their IMA, which did not offer the affordance of integrating the bot. Future studies can analyse the use of these bots for immediate responses to the registration process.

4.3.5. Assessment: Facilitator (Reflections of Classroom Practice and Training Other Teachers), LMS (MCQ), and Peer-Assessed (Lesson Plans)

Peer assessment was introduced for the very first time in the June 2020 run of the certificate course that had more than 400 teachers. A lesson plan assignment was selected for peer assignment, which had more scope for improvement with multiple feedback from peers before it could be implemented with students. The lesson plan assignment, which was earlier graded by a course facilitator, was re-designed to allow teacher peers to grade and give feedback to each other (Appendix A Figure A5 and Figure A6). Resources in the form of small videos were created to support learners in accessing and using peer assessment tools on TISSx. Besides supporting scale, from the pedagogic perspective, the peer assessment was designed to foster collaboration, sharing, and confidence to provide feedback to their peers. The LMS system randomly assigned each lesson plan submission to three peers. Teachers’ interviews and survey data threw some light on the usefulness and challenges of peer assessment, which will be discussed later in this paper.

A digital portfolio seemed difficult to continue as an assessment due to the difficulty perceived in scaffolding larger numbers of teachers to create them at the end of the course. This deletion needs more probing and analysis through further research.

4.3.6. Recognition

Both the certificate with academic credentials from TISS and the digital badge with embedded logos of funders and state governments were used in this phase. Given the paucity of time and budgets, most certificate and digital badge distribution events were organised in online mode even after the CLP.

Introducing Digital Badges: With the partnership with Open University, UK, digital badges were introduced as an alternative to certificates as a form of recognition. This new credential for acknowledgement was adopted for the following reasons: it allowed flexibility to chunk the courses without a lengthy process of seeking permissions from an academic body, allowed exit routes for teachers after each badge course of shorter duration than the certificate course, was promising for larger shareability with clickable details on achievements, seemed modern and cutting edge, offered new and fresh packaging of the old course, and allowed flexibility to add state and funders’ logos on the badge, thus giving credits to the state as their logo was allowed on the digital badge (not on a certificate issued by the university) for pioneering something new and innovative.

4.3.7. Scale

Two thousand four hundred and seventy-seven teachers completed the certificate course and/or received the digital badges in this phase, who then trained around 8000 teachers in the PBLT as a requirement of completing the course.

4.3.8. Summary of Analysis from the Studies/Data Conducted/Collected in Phase 3

Most useful learning support perceived by the teachers: The post-course survey analysis, Table 1 (N = 79 teachers who completed at least one digital badge course), revealed that most of the teachers (85%) indicated that they often read messages on IMA and sought help and advice (45%) on IMA (either WhatsApp or Telegram) for the course [28].

Table 1.

Frequency of online course interactions from post-course survey [28,29].

Value of peer assessment: Peer assessment was found to be much appreciated by many teachers in the post-course survey [28], mostly for the opportunity to receive feedback from peers.

Teachers’ perceptions about peer assessment: For the purpose of this paper, analysis was conducted on the interview data on peer assessment collected in the year 2021 [28]. The research consultants who conducted the interviews were oriented on the process and context of digital badges and were conversant in the language of the teachers. Interviews were transcribed in English, and thematic analysis with frequency was undertaken to understand the results. Twenty teachers out of the forty-six teachers who completed both pre- and post-course surveys for the first digital badge were selected based on proportionate random sampling using criteria such as the language of the course, rural-semi-urban, and gender. One of the aspects covered in these interviews was the value of the inclusion of peer assessments. Thirteen out of twenty participants indicated that peer assessment was one of their favourite modes of assessment in the course, as it allowed them to learn from perspectives other than their own and allowed them to make mistakes in their plans and rectify them after feedback and before they could implement the plans in their classrooms. One participant also indicated that knowing her peers would be assessing her lesson plans made her more conscious of the quality and effort in developing lesson plans. On the other hand, 8 out of the 20 participants indicated they were unhappy with the marks (grades) or the comments received from their peers on the lesson plans. Some of these eight participants indicated that peers from other subject areas might not fully understand the lesson plans created by them and hence might have given them lower grades (marks) than expected. The interview data further suggested that while participants believed that peer assessments allowed for knowledge and feedback sharing among peers, some of the responses suggested it be monitored by the faculty of the course in order to maintain the quality and reliability of feedback and grades assigned.

Teachers’ perceptions about the value of digital badges: The post-course completion survey data collected from 87 teachers who completed at least one digital badge revealed that 30% of teachers preferred a certificate over a digital badge [28] Thus, from the teacher participants’ perspectives, the results were ambivalent on preference for a digital badge over a certificate for recognising accomplishment in the course. Some of the reasons given for this preference were the non-familiarity of their colleagues and authorities with the digital badge and the limitation in sharing the badge digitally due to infrastructure issues. Given here are some of the quotes from the participants:

- “Certificate is a written document which we can keep with us. A digital badge may not open due to network issues.”

- “A certificate for TPD is highly sought for to be produced whenever needed. Digital badge can only be accessed digitally.”

- “Most people, including teachers, do not understand the digital badge. They need it in hard copy.”

- “Many people do not use social media frequently. So, it is difficult to discuss the badge. We cannot show the badge to all.”

- “The elders may face difficulties as they are not familiar with ICT. The environment in the village area and weak education technology infrastructures may stand as barriers into its development.”

Twenty-six per cent of the teacher participants said that a badge was a better recognition than certificates. Some of the reasons given for their choice were ease of sharing on digital/social media platforms, portability, storability, and providing a detailed account of accomplishment. Here are some of the quotes from the participant teachers:

- “In the present world, all livelihood and all means of education has been turned digital and that is why digital badge is very important.”

- “It is beneficial for us as we share it on social media and there is no possibility of losing it in the near future.”

- “We can show this through social media to our students. We can store this on the phone. We can use it at any moment.”

- “It can be stored permanently and can be shared quickly with anyone.”

- “The printed certificates are vulnerable to loss and damage due to various reasons. Also, these do not reflect what a learner has achieved while getting. … Digital badges on the other hand are well organized and kept at one repository, Badgr account, and are easy to use and share when required. Also, these are free from misuse as clicking on the badge reveals the details of the recipient and the activities done to achieve the badge.”

Twenty-five per cent were neutral on their preference or gave a different response not related to their preference, and approximately 18% did not respond to this question in the survey.

Sharing of digital badges: One of the advantages of popular literature on digital badges is their potential to be shared widely using social media platforms [28]. The post-course completion survey data from 87 teachers who completed at least one digital badge stated that although the teacher participants were divided on their views on digital badges over certificates, many teacher participants acknowledged the shareability feature of the digital badges. When particularly asked if and where they shared their digital badges, the teacher participants reported that they widely shared their digital badges from this course. When asked what digital platforms they used to share their badges, Facebook (62%) was reported to be the most used social media platform, compared to Instagram (5%) and LinkedIn (1%). IMAs such as Telegram (62%) and WhatsApp (71%) were also reported to be used for sharing digital badges by many teacher participants. Some of the teacher participants used e-mail (22%) and their school websites (8%) to share their badges. Many (74%) teacher participants indicated that they shared their badges in their school community (headmaster and peers) and with their family and friends (68%). A few (26%) teacher participants also reported sharing their badges with the parents of their students.

Some of the open-ended responses in the survey highlighted the teacher participants’ joy of sharing the digital badges, which motivated them to take more digital badge courses and also made them ambassadors of the digital badge course:

- “I shared my first digital badge on many platforms and received a lot of appreciation. This encouraged me to accomplish other courses and get two more digital badges.”

- “When I shared my badge to our head teacher and colleague they congratulated me and they showed interest in taking the Digital Badge course in future.”

- “I shared my Digital Badge with some friends residing in Guwahati via WhatsApp. They were very excited about it and wanted to know more about it. I shared my experiences with them.”

- “I shared it on social media and people greeted me and wanted to know how to do such courses.”

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The comparative analysis of cases of TPD brought to light the progressive use of leading-edge technologies across the three phases that facilitated scale, continuity, practice-based learning support, seamless communication, collaboration, adaptability, recognition with shareability, and transferability of learning in other contexts.

The use of LMS and IMA technologies supported blended and online modes and significantly scaled the numbers of teachers reached (completed course/workshop) linearly across phases of TPD. Besides scale, these technologies allowed longer and continuous engagement with the course (6 to 12 weeks of blended or online course versus only three to four days of F2F workshops in Phase 1).

The continuity of distance mode in Phase 2 and Phase 3 was supported with rigorous learning support. The studies presented in Phase 2 reiterated that higher participation in CoP groups was related to better performance in the course. The technologies for learning support in Phase 3 were upgraded (switching to Telegram, adding a chatbot, separating groups for and by peer mentors, weekly reminder postings on IMA and e-mail, and online classes) to handle scale and alienation due to the lack of any F2F contact. The online class with course faculty revisiting some of the key concepts from the course also enabled replicating face-to-face academic environments, which teachers are familiar with and value [8].

The post-course survey and interview data analysis presented in Phase 3 indicated teachers’ related contribution of CoP groups and discussion forums to their success in completing the course. These results also point to the feature of collaborative learning afforded by IMA and LMS. Another aspect of technology-enabled collaborative learning could be seen through peer assessment. As presented in the Phase 3 analysis, the peer assessment enabled by the TISSx LMS was found to be a preferred type of assessment by many teachers who felt peer assessment shared with them the work of their peers and motivated them to perform better.

Multiple technology and tools allowed more flexibility or adaptability for the teachers to engage with the course. The TISSx LMS was made accessible from both desktop/laptop and smartphones through the TISSx app; the blend of synchronous and asynchronous offerings helped teachers with low internet connectivity balance their time and connectivity spots for engaging with the course.

The data analysis presented in Phase 3 showed that with the introduction of digital badges as an added recognition, the shareability of the accomplishments improved in terms of posting on different digital platforms/IMA/social media, indicating more motivation for many teachers.

Lastly, data from Phase 2 indicates that TPD contributes to sustainability, and the learning was also transferable in newer contexts [9,19]. Both the studies presented in Phase 2 indicated that teachers were able to transfer PBLT in their classrooms and in newer contexts such as CLP [7,27], thus directly benefitting the learners.

Similarly, future studies on the sustainability of teachers’ practice of CTLT and PBLT can be conducted for Phase 3 (totally online mode), also throwing light on their relevance and sustainability in post-CLP.

The frameworks in this paper presented features of innovative use of technologies and pedagogies that educated teachers on constructivist technologies in their subject teaching. The paper further documented evidence of these teachers transferring their pedagogic knowledge in real classrooms, thus, directly benefitting students’ learning using PBLT in F2F classrooms and later also in the CLP.

The frameworks presented here can be used to guide technology-enabled TPD for large-scale implementation in Indian middle and secondary education. Further, research through pathway analysis between technologies, pedagogies, and innovative features in TPD over time can be undertaken to establish frameworks presented in this paper.

Author Contributions

Methodology, A.C.; Formal analysis, S.S. and D.S.; Data curation, A.C., S.P. and S.S.; Writing—original draft, A.C.; Writing—review and editing, A.C., S.P., S.S. and U.B.; Visualisation, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Capgemini, UNICEF India, Open University, UK, and Tata Trusts.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All the data collection methods used in this paper and its documented studies have approval from the Institutional Review Board at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data and studies used in this paper can be availed on request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the efforts of the various state education authorities and teachers who were part of this initiative and research study. Special thanks to the guest editor of this special issue and the reviewers of the article for their expert comments, editorial team manager, and Nishevita Jayendran for her review and edits.

Conflicts of Interest

The study and its authors have no known conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Screenshot of the course content on Moodle platform during Phase 2.

Figure A2.

Course Outline for two credits online course.

Figure A3.

Snippet of Discussion Forum on TISSx platform.

Figure A4.

Snippet of Discussion Forum in regional language on TISSx platform (in this case the discussion posts are in Bangali, a language primarily spoken in the Indian state of West Bengal.

Figure A5.

Snippet of instructions for peer assessment for learners on TISSx platform.

Figure A6.

Snippet of peer assessment on TISSx platform.

References

- Charania, A.; Sen, S.; Sarkar, D.; Singh, R.; Dutta Mazumdar, B.; Adinolfi, L. Features of Innovative Use of Technology during the COVID-19 Period in India. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Computers in Education (WCCE), Hiroshima, Japan, 21–24 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfart, O.; Trumler, T.; Wagner, I. The unique effects of COVID-19—A qualitative study of the factors that influence teachers’ acceptance and usage of digital tools. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 7359–7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charania, A. (Ed.) Integrated Approach to Technology in Education in India: Implementation and Impact; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; Taylor and Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Council of Educational Research & Training (NCERT). National Curricular Framework 2005; National Council for Education Research and Training: New Delhi, India, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Government of India. The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act; Ministry of Law and Justice: New Delhi, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Annual Status of Education Report (ASER). In Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) 2018 (Provisional); ASER Centre: New Delhi, India, 2017; Available online: http://img.asercentre.org/docs/ASER%202018/Release%20Material/aserreport2018.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Charania, A.; Bakshani, U.; Paltiwale, S.; Kaur, I.; Nasrin, N. Constructivist teaching and learning with technologies in the COVID-19 lockdown in Eastern India. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1478–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD). National Education Policy 2020; MHRD; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2020. Available online: https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Darling-Hammond, L. Strengthening Clinical Preparation: The Holy Grail of Teacher Education. Peabody J. Educ. 2014, 89, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, R. (Ed.) A framework for ICT policies to transform education. In Transforming Education: The Power of ICT Policies; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Developmentally Appropriate Technology in Early Childhood (DATEC) Project. 2001. Available online: https://www.ioe.ac.uk/cdl/DATEC (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Rosas, R.; Nussbaum, M.; Cumsille, P.; Marianov, V.; Correa, M.; Flores, P.; Grau, V.; Lagos, F.; López, X.; López, V.; et al. Beyond Nintendo: Design and assessment of educational video games for first and second grade students. Comput. Educ. 2003, 40, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.D. Leading Edge Online Classroom Education: Incorporating Best Practices Beyond Technology. Am. J. Bus. Educ. (AJBE) 2018, 11, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, J. A Black Swan in a Sea of White Noise: Using Technology-Enhanced Learning to Afford Educational Inclusivity for Learners with Asperger’s Syndrome. Soc. Incl. 2015, 3, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.-L. A Collaborative Action Research about Making Self-Advocacy Videos with People with Intellectual Disabilities. Soc. Incl. 2015, 3, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, A. (Ed.) Preparing Teachers and Developing School Leaders for the 21st Century: Lessons from around the World; International Summit on the Teaching Profession; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, K. Invite Students to Co-Design Their Learning Environment. 2018. Available online: https://www.iste.org/explore/In-the-classroom/Invite-students-to-co-design-their-learning-environment (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- Crandall, D.P. The teacher’s role in school improvement. Educ. Leadersh. 1983, 41, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Trucano, M. Knowledge Maps: ICTs in Education. 2005. Available online: http://www.infodev.org/en/Publication.8.html (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Hyler, M.E.; Gardner, M. Effective Teacher Professional Development; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/teacher-prof-dev (accessed on 23 June 2019).

- Dede, C. Comparing frameworks for 21st century skills. In 21st Century Skills Rethinking How Students Learn; Bellance, J., Brandt, R., Eds.; Solution Tree Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2010; pp. 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, M.; Mishra, N. What Is Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)? Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 2009, 9, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Paltiwale, S. Whatsapp_plots, Gitlab Repository. Available online: https://gitlab.com/sumeghhp/whatsapp_plots (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Paltiwale, S.; Sarkar, D.; Charania, A. Use of Community of practices for in-service government teachers in professional development. In Empowering Teaching for Digital Equity and Agency; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Basak, S.; Halsana, M.; Ansari, S.H.; Datta, M. Authentic Learning through Project-Based Learning in ITE. In Proceedings of the Open Conference on Computers in Education (OCCE), Mumbai, India, 6–8 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Charania, A.; Singh, R.; Borthakur, K.; Ansari, S.; Halsana, M.; Kaur, I.; Bakshani, U.; Basak, S. Use of ICT for Active Teaching and Learning in the Indian Government Secondary Schools during the Lockdown 2020. In Teaching, Technology and Teacher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Stories from the Field; Ferdig, R.E., Baumgartner, E., Hartshorne, R., Kaplan-Rakowski, R., Mouza, C., Eds.; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE): Waynesville, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, S.; Charania, A.; Wolfenden, F.; Adinolfi, L.; Sohini, S.; Sarkar, D. Digital Badges for TPD at scale in the Global South: A Framework for Implementation and Field Study in Assam, India. 1 August 2022. Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/85097/ (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Sen, S.; Charania, A.; Sarkar, D. Implementation Strategies and Challenges in an Online Teacher Professional Development Program in the COVID-19 context. In Proceedings of the SITE Interactive Conference, Online, 26–28 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Esterberg, K.G. Qualitative Methods in Social Research; The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Charania, A.; Nagrale, S.; Singh, R.; Avadhanam, R.; Kaur, I. Assessing ICT Enabled Learning Artefacts through Rubrics in Eastern India. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Conference of Education, Seville, Spain, 11–13 November 2019; pp. 10994–10998. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, N.; Tolson, D.; Ferguson, D. Building on Wenger: Communities of practice in nursing. Nurse Educ. Today 2008, 28, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson-Smith, E. Online communities of practice. In The encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Encycl. Appl. Linguist. 2013, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltiwale, S.; Charania, A. Understanding the teacher participation and interaction over technology-enabled CoP. In Proceedings of the SITE Interactive Conference, Online, 26 October 2021; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE): Waynesville, NC, USA, 2021; pp. 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Niederhauser, D.S.; Lindstrom, D.L. Instruction technology integration models and frameworks: Diffusion, competencies, attitudes and dispositions. In Second International Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education; Voogt, J., Knezek, G., Christensen, C., Lai, K.-W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.A.; Satyawada, R.S.; Goel, T.; Sarangapani, P.; Jayendran, N. Use of EdTech in Indian school education during COVID-19: A reality check. Econ. Political Wkly. 2020, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas, A. Status Report-Government and Private Schools during COVID-19; Oxfam: New Delhi, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Charania, A.; Wolfenden, F.; Sarkar, D.; Cross, S.; Sen, S.; Adinolfi, L. Teacher motivation and aspiration for online mentoring their fellow teachers in the COVID lockdown period. In Proceedings of the SITE Interactive Conference, Online, 26–28 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pratham. Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) 2020: Wave 1; ASER Centre: New Delhi, India, 2020; Available online: http://img.asercentre.org/docs/ASER%202020/ASER%202020%20REPORT/aser2020fullreport.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).