A Conceptual Model of the Factors Affecting Education Policy Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Higher Education and the Current Situation in Yemen

1.2. A Brief Synthesis of NSDHE Policy

To create a higher education system characterized by quality, broad participation, multiple and open routes vertically and horizontally, that is effective and efficient and delivers quality programs, shows excellence in teaching, research and service to society, and enhances Yemen’s quality of life.[17] (p. 58)

1.3. Policy Makers and Policy Implementers

1.4. Education Policy Formulation: A Brief Overview

1.5. Education Policy Implementation and Key Influential Factors

2. Research Design

2.1. Research Methods

2.2. Stages of the Interviews and the Selection of Participants

2.3. Research Participants

2.4. Research Interpretation Methods

3. Research Evidence

3.1. Implementers’ Lack of Information about the Strategy and University Leaders’ Lack of Commitment

The strategy is not available online or at our university. Teachers read the document regarding the laws concerning higher education to know the rules about getting promotions or financial increments.TE10

Frankly speaking, I do not know whether or not there is a policy in my program.ST17

There is no updating of the curricula, and not all of the objectives are implemented. First, I would like to say that this strategy… unfortunately did not extend to the universities.D2

The National Strategy of Higher Education is kept hidden away in drawers. It is not implemented.VD4

I did not read the strategy, and I have not seen any commitment from the university to announce it or make it public. The university does not even inform teachers of what duties they have to perform. We do not have an educational policy for the programme. There are no objectives we have to achieve.TE19

We do not have an ambitious administration. If we had an ambitious administration, commitment, and good intentions, it would be possible—with just small financial support—to achieve many things. There is no commitment from the university leaders even to encourage teachers to read the strategy.VD2

Our administration is responsible for financial and administrative issues. Academic and educational matters are not our concern. Such issues concern those specialized in academia. I am the secretary general, but this topic does not concern me too much. However, we always stand by the academics and tell them that we need to deal with financial matters to develop the educational process… I hope that university leaders and those in colleges consider this matter.BA1

3.2. Strategy Top-Down Planning

Top leaders think that they know everything and are the owners of philosophy in this field. … Therefore, they think it is they who ought to plan and prepare strategies (without involving other actors with knowledge in the field).VD6

I think the achievement is very low. Maybe it is because the strategy was prepared by an external expert. Or perhaps it was owing to a lack of resources in this country.TE15

An external expert was invited to study the situation in Yemen. He... wrote a report that later became used for strategy… The Ministry of Higher Education lacked a mechanism for enforcing the strategy on universities, and it required them to prepare their own strategy.TE1

3.3. Funding and Financial Corruption

It is possible that administrative and financial corruption is one of the main factors in the strategy’s implementation. There is still a lack of concern about scientific research among academics, and the research suffers considerably as a result.TE1

The strategy is not implemented because of administrative and financial corruption in the government as a whole and also at the university.TE5

The objectives of the strategy are not implemented. It seems that those in higher positions prepared the strategy to gain financial support from international organizations… The culture of corruption is what threatens society. Such culture exists at the university from the top to the bottom. Unfortunately, if you do not go along with that culture, accusations are made against you.VD1

There are no encouraging efforts for conducting research. Nowadays, there is no financing for improving research. At one time, there was some budget devoted to improving research. However, due to the current war, there is no longer any support.D7

There is no encouragement to do research. Today, there is no financing for promotions. Teachers can get academic promotions but no financial incentives.VD4

About encouraging research, I think scientific research is not given its due in Yemen in general and at universities in particular. It is not considered either in terms of finance or supervision.VD6

When we talk about the strategy objectives, we know that we need funding to achieve such objectives. Currently, we are discussing funding our journal. … We should publish it quarterly, but we cannot because there is no funding to support researchers at the moment. … The government itself has no direction [about improving research].AA3

Every strategy needs funding for its implementation, but this is not happening because of the current situation in Yemen. … Even though there are strategies for improvement, the strategies will not be implemented because there is no commitment from those in authority to fund such an implementation.AA2

3.4. Institutional Strategy: Vision and Mission

There are no institutional strategies for fulfilling the goals of the ministry of higher education.TE12

It is possible that all universities in Yemen have neither vision nor mission.TE21

Frankly speaking, I did not read the strategy. However, based on the current situation I see, there is neither an educational policy at my college nor in the department.TE17

We do not have an educational policy for the programme. There are no objectives we have to achieve.TE19

We have just started to organize workshops on developing a college strategy. Next week, we will hold a workshop for introducing such a strategy. We did not have a previous strategy for the college or even objectives for the present programs.D9

We are currently preparing a strategic plan for the university that includes the university’s aims, vision, and mission. From this general strategy, we will work on creating a strategy for each college, centre, or unit within the university. We will then do the same thing with departments and will focus on improving the curricula.D3

There was no strategic thinking at the university until 2011, when we started plans to prepare an institutional strategic policy.AA1

We are currently working on preparations for our institutional strategy, which will have the same objectives as the National Strategy of Higher Education.AA3

3.5. Eco-Political Situation: Implementation Period

It was crystal clear that the Yemeni government could not succeed in achieving political stability in the country: there were many tribal problems as well as partisanship problems in every city.AA2

The strategy is too ambitious because the period devoted to implementation is completely insufficient. The economic and security conditions in Yemen have also hindered its implementation.VD6

3.6. Basic Infrastructure: Classrooms, Laboratories, Offices, Toilets, and Teaching Aids

An aspiration should be that all departments should have offices for their staff, with secretarial support, internet connections… (and) staff should feel that they are being treated equitably, and their workloads—in particular, their teaching loans—should be fairly distributed, on some sort of formulaic basis.[17] (p. 89)

We assemble in a single classroom (during educational courses), and that causes problems with understanding because we cannot hear the lecturer well. That leads to a feeling of boredom during the class.ST11

The main deficiency here is suitable classrooms. For the past four years, we have been taught in the same room, which is lacking in many areas—even comfortable chairs.ST8

For our programme, there are two small teaching rooms, which are made of steel. Most of our classes are held around noon, when either the sun’s heat is too strong or it is raining. Both affect our ability to understand the content of the lectures.ST21

We study in teaching rooms made of steel, and when it rains, we cannot hear anything. We also suffer because of the heat of the sun.ST24

We have spent four years studying in an underground lecture room. Whenever I have a class, the darkness of the lecture room makes me feel very angry. We feel oppressed in this programme—especially in the lecture rooms.ST31

Sometimes, I have to go home to use the toilet. There are no places where we can relax, such as when we want to eat something. It is difficult to deal with this situation, and we feel that the authorities do not care about us.ST25

There is sometimes no lecture room available for us because of a change in the schedule. In addition, when we go to the new assigned room, we find it is full. Therefore, we waste too much time waiting for a room to become vacant. If we need to go to the toilet, we have to use those at the mosque.ST17

There are no rooms for us to put our things. There is only one office for all the teachers, and if you arrive late, you find no available chairs. When I discussed this matter with the vice dean of the college, who was responsible for general affairs, he told me that he also has no office.TE7

I am a chairperson, but I do not have an office. … I do not have a place to keep my documents or those of my students. If there is any problem at the department, I am the first person to deal with the situation, but the authorities do not consider our needs.TE16

Unfortunately, the lecture rooms in our colleges are inappropriate for teaching and learning, and the number is insufficient. We report our problems to the university leadership, but no action has been taken yet.D9

Our college (Science College) was established, though we did not have our own building. In the 20 years since then, we have acquired only two lecture rooms and a few rooms are used as laboratories, but they have old apparatuses.D6

One problem for our teaching staff is all of them having to use a single office. They do not have computers on their desks. … There are toilets in our college [arts college], but they do not have water.D7

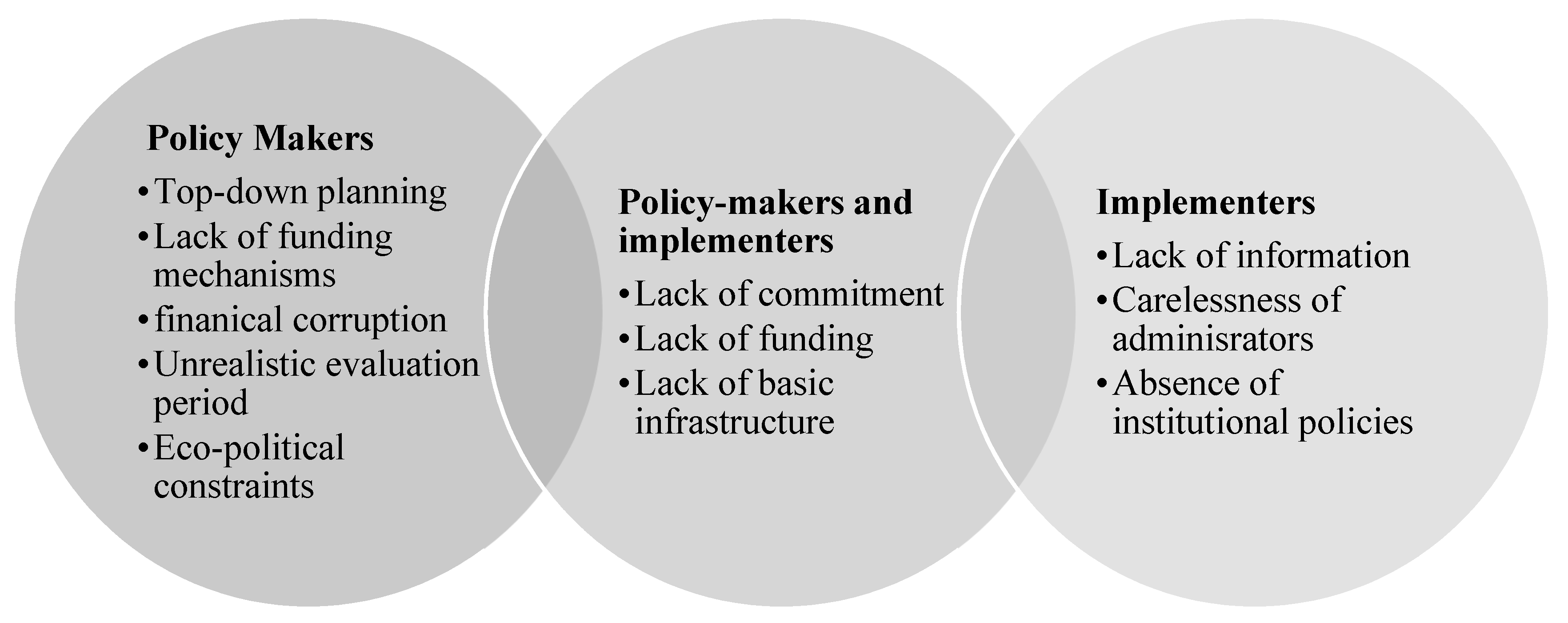

3.7. A Conceptual Model of the Key Factors of the Implementation Failure

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clarke, M.; Killeavy, M. Charting teacher education policy in the republic of Ireland with particular reference to the impact of economic recession. Educ. Res. 2012, 54, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagin, D.A. Free Teacher Education Policy Implementation in China. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jasman, A.N. A critical analysis of initial teacher education policy in Australia and England: Past, present and possible futures. Teach. Dev. Int. J. Teach. Prof. Dev. 2009, 13, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Analysis of the Implementation of Teacher Education Policy in China Since 1990S: A Case Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Muthanna, A.; Karaman, A.C. The need for change in teacher education in Yemen: The beliefs of prospective language teachers. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 12, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthanna, A.; Karaman, A.C. Higher education challenges in Yemen: Discourses on English teacher education. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2014, 37, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthanna, A. Exploring the Beliefs of Teacher Educators, Students, and Administrators: A Case Study of the English Language Teacher Education Program in Yemen. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Muthanna, A. A tragic educational experience: Academic injustice in higher education institutions in Yemen. Policy Futures Educ. 2013, 11, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Development Center. Yemen Cross-Sectoral Youth Assessment: Final Report; USAID & EQUIP3: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Muthanna, A.; Sang, G. Brain drain in higher education: Critical voices on teacher education in Yemen. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2018, 16, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthanna, A. Quality education improvement: Yemen and the problem of the ‘brain drain’. Policy Futures Educ. 2015, 13, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthanna, A. Plagiarism: A shared responsibility of all, current situation, and future actions in Yemen. Account. Res. 2016, 23, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthanna, A.; Sang, G. Conflict at higher education institutions: Factors and solutions for Yemen. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2018, 48, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthanna, A.; Almahfali, M.; Haidar, H. The interaction of war impacts on education: Experiences of school teachers and leaders. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNSECO. Global Education Monitoring Report: Education for People and Planet-Creating Sustainable Futures for All. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO. 2016. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245752/PDF/245752eng.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2017).

- Clausen, M.-L. Understanding the crisis in Yemen: Evaluating competing narratives. Int. Insp. Ital. J. Int. Aff. 2015, 50, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Higher Studies and Scientific Research. The National Strategy for the Development of Higher Education in Yemen. 2005. Available online: http://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/upload/Yemen/Yemen_Higher_Education_Strategy.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2014).

- Ball, S.J.; Maguire, M.; Braun, A.; Hoskins, K. Policy actors: Doing policy work in schools. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2011, 32, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R. China’s Intellectual Dilemma: Politics and University Enrolment, 1949–1978; University of British Columbia Press: Vancouver, Canada, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Chilton, P.; Schaffner, C. Introduction: Themes and principles in the analysis of political discourse. In Politics as Text and Talk: Analytic Approaches to Political Discourse; Chilton, P., Schaffner, C., Eds.; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, N.; Hardy, C. Discourse Analysis: Investigating Processes of Social Construction; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Examining Massification Policies and their Consequences for Equality in Chinese higher Education: A Cultural Perspective. High. Educ. 2012, 64, 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S.J.; Maguire, M.; Braun, A. How Schools Do Policy. Policy enactments in Secondary Schools; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman, J.L.; Wildavsky, A. Implementation, 3rd ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hjern, B. Implementing research-the link gone missing. J. Public Policy 1982, 2, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D. The Art of Muddling Through: Policy-Making and Implementation in the Field of Welfare; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hasenfeld, Y.; Brock, T. Implementation of social policy revisited. Adm. Soc. 1991, 22, 451–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazmanian, D.A.; Sabatier, B.A. Implementation and Public Policy; Scot, Foresman: Glenville, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, B.A. Top-down and bottom-up approaches to implementation research: A critical analysis and suggested synthesis. J. Public Policy 1986, 6, 12–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.; Hupe, P.C. Implementing Public Policy; Sage: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, C.; Mills, M. Sketching alternative visions of schooling. Soc. Altern. 2011, 30, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, J.; Robinson, J. “Give me air not shelter”: Critical tales of a policy case of student re-arrangement from beyond school. J. Educ. Policy 2015, 30, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity; Routledge: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gowlett, C.; Keddie, A.; Mills, M.; Renshaw, P.; Christie, P.; Geelan, D.; Monk, S. Using Butler to understand the multiplicity and variability of policy reception. J. Educ. Policy 2015, 30, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasman, A.; Blass, E.; Shelley, S. Becoming an academic for the twenty-first century: What will count as teaching quality in higher education. Policy Futur. Educ. 2013, 11, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W. Implementation analysis and assessment. In Social Program Implementation; Williams, W., Elmore, R., Eds.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1982; pp. 267–292. [Google Scholar]

- Honig, M.I. Complexity and policy implementation: Challenges and opportunities for the field. In New Directions in Education Policy Implementation: Conflicting Complexity; Honig, M.I., Ed.; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fitz, J. Implementation research and education policy: Practice and prospects. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 1994, 42, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, C.E.; Stein, M.K. Communities of practice theory and the role of teacher professional community in policy implementation. In New Directions in Education Policy Implementation: Conflicting Complexity; Honig, M.I., Ed.; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, W.D.; Young, T. Editorial: Education policy implementation revisited. Educ. Policy 2015, 29, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hogwood, B.W.; Gunn, L.A. Policy Analysis for the Real World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gerston, L.N. Public policymaking: Process and Principles, 2nd ed.; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Odden, A. Education Policy Implementation; SUNY Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J. Rational choice theory, public policy and the liberal state. Policy Sci. 1993, 26, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannaway, J.; Woodroffe, N. Policy Instruments in Education. Rev. Res. Educ. 2003, 27, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D. Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fok, P.K.; Kennedy, K.J.; Chan JK, S. Teachers, policymakers and project learning: The questionable use of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ policy instruments to influence the implementation of curriculum reform in Hong Kong. Int. J. Educ. Policy Leadersh. 2010, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meter, D.S.; Van Horn, G.E. The policy implementation process: A conceptual framework. Adm. Soc. 1975, 6, 445–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.T. Title of I of ESEA: The politics of implementing federal education reform. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1971, 41, 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, P. The study of macro- and micro-implementation. Public Policy 1978, 26, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mazmanian, D.A.; Sabatier, B.A. Implementation and Public Policy; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A.B.; Moore, J.B. The wording of policy: Does it make any difference in implementation? J. Educ. Adm. 1990, 28, 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tee, N.P. Education policy rhetoric and reality gap: A reflection. Int. J. Educ. Management. 2008, 22, 595–602. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A.; Frey, J.H. The interview: From neutral stance to political involvement. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2005; pp. 695–727. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, R.C.; Biklen, S.K. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods, 5th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed.; Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 509–536. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Grounded Theory Methods; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gall, M.D.; Gall, J.P.; Borg, W.R. Educational Research: An Introduction, 7th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- UNSECO. EFA Global Monitoring Report. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO. 2005. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001373/137333e.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2016).

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP) & Regional Bureau for Arab States (RBAS). Arab Human Development Report 2009: Challenges to Human Security in the Arab Countries; UN Plaza: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/HDR/ahdr2009e.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2016).

- McDonnell, L.M. The politics of education: Influencing policy and beyond. In the State of Education Policy Research; Fuhrman, C.S., Mosher, F., Eds.; Lawrence, Erlbaum Association, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, S.A. Editorial. Policy Futures Educ. 2016, 14, 515–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, P.; Blass, E. Editorial: Higher education futures. Policy Futures Educ. 2013, 11, 658–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, K.S. Analysing policy contexts as a political strategy. Policy Futures Educ. 2014, 12, 707–717. [Google Scholar]

- Wittrock, B.; Lindstrom, S.; Zetterberg, K. Implementation beyond hierarchy: Swedish energy research policy. Eur. J. Political Res. 1982, 10, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant’s Code | Age | Gender | Role | Academic (Rank) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrators | |||||

| AA1 | 48 | M | Chancellor | Assoc. Professor | |

| Lecturer | |||||

| AA2 | 52 | M | Academic affairs vice chancellor | Professor | |

| Lecturer | |||||

| AA3 | 54 | M | Higher studies and scientific research vice chancellor | Assist. Professor | |

| Lecturer | |||||

| BA1 | 50 | M | University secretary general | BA | |

| BA2 | 41 | M | Scientific research administration manager | BA | |

| BA3 | 45 | M | Planning and statistics manager | BA | |

| BA4 | 47 | M | Science faculty secretary general | BA | |

| BA5 | 56 | M | Finance administration general manager | BA | |

| BA6 | 38 | M | Arts faculty student affairs manager | BA | |

| BA7 | 45 | M | University general registrar | BA | |

| BA8 | 48 | M | Arts faculty general secretary | BA | |

| BA9 | 39 | M | Science faculty student affair manager | BA | |

| Deans | |||||

| D1 | 43 | M | Library | Assist. Professor | |

| D2 | 58 | M | Educational & psychological counselling centre | Professor | |

| D3 | 39 | M | Academic improvement and quality assurance unit | Assoc. Professor | |

| D4 | 39 | M | Dentistry College | Assist. Professor | |

| D5 | 42 | M | Agriculture College | Assoc. Professor | |

| D6 | 48 | M | Science College | Assoc. Professor | |

| D7 | 50 | M | Arts College | Professor | |

| D8 | 45 | F | Rehabilitation and educational research centre | Assoc. Professor | |

| D9 | 45 | M | Education College | Assoc. Professor | |

| Vice Deans | |||||

| VD1 | 44 | M | Education college environmental affairs and society service | Assoc. Professor | |

| VD2 | 50 | M | Education college higher studies | Assoc. Professor | |

| VD3 | 37 | M | Education college students affairs | Assist. Professor | |

| VD4 | 40 | M | Education college academic affairs | Assist. Professor | |

| VD5 | 40 | M | Education college quality assurance & Adults TE Program Chair | Assoc. Professor | |

| VD6 | 41 | M | Academic accreditation and quality assurance unit | Assist. Professor | |

| Teacher educators | |||||

| Participant’s code | Age | Gender | Programme | Role | Rank |

| TE1 | 56 | M | Administration and educational foundations | Lecturer | Professor |

| TE2 | 53 | M | Lecturer | Professor | |

| TE3 | 43 | M | Chairperson | Assist. Professor | |

| TE4 | 40 | M | Lecturer | Assist. Professor | |

| TE5 | 38 | M | Psychology TEP | Chairperson | Assist. Professor |

| TE6 | 40 | M | Lecturer | Assist. Professor | |

| TE7 | 40 | M | Lecturer | Assist. Professor | |

| TE8 | 51 | M | Lecturer | Assist. Professor | |

| TE9 | 42 | M | Lecturer | Assist. Professor | |

| TE10 | 38 | M | Lecturer | Assist. Professor | |

| TE11 | 38 | M | Art Education TEP | Chairperson | Assist. Professor |

| TE12 | 28 | F | Lecturer | Teaching Assistant | |

| TE13 | 47 | M | Arabic TEP | Chairperson | Assist. Professor |

| TE14 | 54 | M | Lecturer | Professor | |

| TE15 | 43 | M | Educational Rehabilitation TEP | Chairperson | Assist. Professor |

| TE16 | 43 | M | Chemistry TEP | Chairperson | Assist. Professor |

| TE17 | 42 | M | Lecturer | Assoc. Professor | |

| TE18 | 47 | M | Quran TEP | Chairperson | Assoc. Professor |

| TE19 | 38 | M | Lecturer | Lecturer | |

| TE20 | 45 | M | Physics TEP | Chairperson | Assist. Professor |

| TE21 | 38 | M | Lecturer | Assist. Professor | |

| TE22 | 42 | M | Lecturer | Assist. Professor | |

| TE23 | 39 | M | Math TEP | Chairperson | Assist. Professor |

| TE24 | 37 | F | Lecturer | Assist. Professor | |

| TE25 | 38 | M | Teacher of Math & Science TEP | Chairperson | Assist. Professor |

| TE26 | 43 | F | Lecturer | Assist. Professor | |

| TE27 | 38 | F | Educational Technology TEP | Chairperson | Assist. Professor |

| TE28 | 34 | M | Lecturer | Lecturer | |

| TE29 | 40 | M | Lecturer | Assist. Professor | |

| TE30 | 44 | M | Lecturer | Assist. Professor | |

| TE31 | 38 | M | Curriculum & Teaching Methodologies TEP | Chairperson | Assist. Professor |

| TE32 | 53 | M | Lecturer | Professor | |

| Teacher Students | |||||

| Participant’s code | Age | Gender | Programme | Current position | |

| TS1 | 24 | F | Quran TEP | Recent graduates | |

| TS2 | 23 | F | |||

| TS3 | 23 | F | Math TEP | ||

| TS4 | 23 | F | |||

| TS5 | 22 | F | Physics TEP | ||

| TS6 | 23 | F | |||

| TS7 | 21 | F | Teacher of Math & Science TEP | ||

| TS8 | 21 | F | |||

| TS9 | 22 | F | Chemistry TEP | ||

| TS10 | 21 | F | |||

| TS11 | 23 | M | |||

| TS12 | 24 | M | Adult TEP | ||

| TS13 | 25 | M | |||

| TS14 | 23 | M | |||

| TS15 | 23 | F | Educational Technology TEP | ||

| TS16 | 23 | F | |||

| TS17 | 38 | M | Administration & Educational Foundation TEP | ||

| TS18 | 42 | M | |||

| TS19 | 34 | M | |||

| TS20 | 36 | M | |||

| TS21 | 23 | F | Art Education TEP | ||

| TS22 | 23 | M | |||

| TS23 | 24 | M | |||

| TS24 | 23 | F | Arabic TEP | ||

| TS25 | 23 | F | |||

| TS26 | 23 | F | Kindergarten TEP (division) | ||

| TS27 | 23 | F | |||

| TS28 | 24 | F | |||

| TS29 | 23 | F | |||

| TS30 | 25 | F | Special Education TEP (division) | ||

| TS31 | 22 | F | |||

| TS32 | 26 | F | Educational Counselling TEP (division) | ||

| TS33 | 23 | F | |||

| TS34 | 23 | F | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muthanna, A.; Sang, G. A Conceptual Model of the Factors Affecting Education Policy Implementation. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030260

Muthanna A, Sang G. A Conceptual Model of the Factors Affecting Education Policy Implementation. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(3):260. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030260

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuthanna, Abdulghani, and Guoyuan Sang. 2023. "A Conceptual Model of the Factors Affecting Education Policy Implementation" Education Sciences 13, no. 3: 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030260

APA StyleMuthanna, A., & Sang, G. (2023). A Conceptual Model of the Factors Affecting Education Policy Implementation. Education Sciences, 13(3), 260. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030260