Abstract

The purpose of this study is to analyze the potential and merits of narrative-based virtual fieldwork in preservice geography teacher education. Virtual fieldwork can effectively complement, implement, and foster fieldwork. In addition, narrative is closely related to fieldwork. To proceed with the research, this study developed a travel geography class for PGTs (primary geography teachers) that included narrative-based fieldwork assignments. This study deduced four themes to illuminate the potential of narrative-based virtual fieldwork (NVF) by using a phenomenographic analysis of the reflective journals written by the participating preservice geography teachers who completed their NVF assignments. The results of this study suggested that the NVF possibly involves the PGTs’ engagement in, procedural and contextual understanding of, and teaching knowledge of virtual fieldwork thanks to its specific characteristic of integrating narrative and virtual fieldwork. The results of this study provide concrete discussions on the potential and merits of NVF in PGTE.

1. Introduction

Fieldwork has particular merits in the geography discipline to provide learners with opportunities to perceive, experience, learn, and inquire about real sites and the world [1,2]. In other words, fieldwork is an essential part of geography education that enables students to develop authentic experiences, learning, and thinking about geographic phenomena and geospacers. This is the reason why the K-12, graduate, and postgraduate geography curricula in many countries emphasize fieldwork [3,4,5].

In addition, fieldwork can be related to narratives. The processes of fieldwork constitute diverse geospatial narratives [6,7]. Moreover, students have various awarenesses, emotions, and experiences of places and regions [8,9]. In other words, students’ own narratives are probably more effective and meaningful fieldwork. For these reasons, some geography education researchers have focused on the integration of fieldwork and narratives [8,10].

Nevertheless, fieldwork is not easy. Budget, safety, and time issues usually impede conducting fieldwork in geography classes [1,9]. This has usually led to the neglect or disregard of fieldwork in geography classes or curricula despite its importance [6]. Moreover, teachers’ insufficient experiences and competencies in fieldwork possibly impede fieldwork in geography classes [2,11].

This problem implies that two issues need to be seriously considered and illuminated. First, effective methods to complement the limits of fieldwork are necessary. Second, geography teacher education should meaningfully cultivate teachers’ competencies in preparing and conducting fieldwork.

In this respect, virtual fieldwork can be a useful method to implement fieldwork in preservice and inservice geography teacher education. Because virtual fieldwork may effectively complement real fieldwork, it possibly encourages preservice geography teachers (PGTs)’ understanding, knowledge, and competencies of fieldwork in the real environment of PGT education (PGTE), which has several limitations in conducting real fieldwork [11].

This study focused on the integration of narrative and virtual fieldwork for PGTE. Narrative is closely related to fieldwork. More particularly, the process of fieldwork has quiet narrative properties, as the diverse fieldwork literature implies [6,12]. In this sense, this study suggests the term “narrative-based virtual fieldwork (NVF)”, a kind of virtual fieldwork using narrative-based geospatial technologies (NGSTs) or narrative formats and structures. NVF probably has specific merits for virtual fieldwork for PGTE because narrative is closely related to geography, fieldwork, and travel [4,13].

To proceed with the research, this study prepared and conducted NVF activities in travel geography classes for PGTs. The participating PGTs’ reflective journals on virtual fieldwork activities were analyzed by phenomenology, a qualitative research methodology specializing in interpreting the meaning of subjective learning and experiences to analyze the potential of NVF in PGTE [14,15]. The results of this study are expected to provide meaningful discussions on fieldwork education and NVF in PGTE.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Virtual Fieldwork and Geography Teacher Education

Fieldwork is particularly important in geography education because fieldwork enables students to experience, learn, and inquire about real and authentic geographical and geospatial features and phenomena [1,16,17,18]. In other words, fieldwork provides students with authentic geography learning. Most importantly, fieldwork has been the significant basis that created and developed geographic knowledge and theories since the ancient era, as Herodotus’s, Ibn Battuta’s, Alexander von Humboldt’s, and Ferdinand von Richthofen’s fieldwork and their contributions to the development of geography show [6,19]. This shows the importance of fieldwork in geography research and education. For these reasons, fieldwork has been emphasized in geography education and curricula and geography education research in many countries [3,4,6,9,16].

Nevertheless, conducting fieldwork in primary, secondary, and even higher classes is not easy. Fieldwork requires a substantive time frame and effort and budget. Moreover, security and safety issues are also closely related to fieldwork [1,2,17]. In other words, fieldwork is essential for geography teaching and learning, but it involves several real limits. These limits seriously impede and even decline the status of fieldwork in geography classes and curricula [2,11].

In this respect, virtual fieldwork using geospatial technologies, such as virtual globes such as Google Earth, remote sensing, geographic information system (GIS), and virtual reality (VR), has significant potential and merits to supplement or foster real fieldwork. Virtual fieldwork provides highly realistic field environments in the classroom and minimizes time, budget, and safety limits by using and integrating 3D satellite mapping, VR, and diverse media [1,2,20,21]. In addition, virtual fieldwork enables students to efficiently renew fieldwork data or content and communicate, share, and assess fieldwork plans, processes, and results because it is generally based on the internet or a mobile network [20,22]. In addition, the possibilities of virtual fieldwork have been more seriously noted in the current COVID-19 pandemic, which has almost blocked opportunities for real fieldwork [23,24,25]. In sum, virtual fieldwork enables teachers and students to efficiently and easily prepare and conduct realistic and effective fieldwork experiences in the classroom.

Geography education researchers have focused on the potential of virtual fieldwork and made efforts to develop virtual fieldwork programs and construct theoretical discussions on the methods, directions, merits, and potential of virtual fieldwork. For example, Bos et al. [20] developed VR-based virtual fieldwork methods to motivate students to engage in fieldwork activities and improve their visual and geospatial competencies in the classroom. Granshaw and Duggan-Haas [2] developed two virtual fieldwork programs, titled “Regional and Local” and “Astrobiology at Yellowstone”, for geology teachers to enhance their geological and physical geographic insights and competencies to prepare and conduct fieldwork in situations where real fieldwork was difficult to perform.

Virtual fieldwork has significant meaning and potential in PGTE. The importance of fieldwork in PGTE is undeniable. Fieldwork is essential for cultivating PGTs’ authentic and contextual geography content knowledge [26]. Furthermore, PGTs should develop insights and competencies in designing, preparing, and conducting fieldwork because geography teachers are the main agent of that work in geography classes [16,23]. In sum, PGTE needs to provide PGTs with opportunities for learning by fieldwork and learning on fieldwork. However, fieldwork in PGTE also faces several limitations, as stated earlier. Those limits discourage PGTs’ engagement in and experiences of fieldwork, and this problem possibly leads to the PGTs’ insufficient understanding of and competencies in fieldwork in geography classes [2]. The contemporary COVID-19 pandemic has been deteriorating such limits of fieldwork in PGTE [25]. This suggests that PGTE should have alternatives to complement the limits of fieldwork.

In this sense, virtual fieldwork can meaningfully and effectively complement such limits thanks to the merits and potential argued earlier. Adopting virtual fieldwork in geography teacher education has already been attempted in the field of geography education research to cultivate teachers’ experiences of and competencies in fieldwork. In fact, geography education researchers have noticed the potential of virtual fieldwork to complement and encourage fieldwork in geography classes since the 1990s [1,17,27,28]. They have discussed that virtual geospatial environments enable students to have highly realistic experiences and learn about geographic spaces and places. In other words, virtual fieldwork possibly realizes “fieldwork in classroom” or “fieldwork on desk.”

Of course, virtual fieldwork cannot become an absolute alternative because it provides highly realistic but not real environments and experiences [1,29]. Real fieldwork enables students to have real experiences in real spaces or places, but virtual fieldwork cannot. In fact, the importance of fieldwork in geography education is based on the real experiences of and insights into real cases of geographic features and phenomena [4,8]. In this respect, virtual fieldwork can effectively complement but cannot completely alter real fieldwork. Many geography education researchers are still focusing on real fieldwork, and they are attempting to utilize virtual fieldwork to complement and facilitate real fieldwork and field courses [1,9,25]. In sum, virtual fieldwork could be understood as a potential method to complement and facilitate real fieldwork or field courses in geography classes.

2.2. Narrative-Based Geospatial Technologies and Virtual Fieldwork

Geospatial technologies enable users or students to investigate, compare, and analyze diverse geospatial features, phenomena, and topics in realistic, diverse, and scalar perspectives by using diverse 3D satellite map layers and multimedia. Thanks to these merits, geospatial technologies have become one of the core topics of geography education research to cultivate students’ and geography teachers’ spatial thinking, map abilities and literacy, geospatial representation, and geography inquiry [19,21,22,30,31,32].

Among diverse geospatial technologies, NGSTs, such as Story Maps and Mapstory, are specialized in geospatially representing diverse narratives, including personal experiences or the topophilia of places, trips and traveling, and historical and historical geographic issues, into geospatial formats by integrating 3D map layers, multimedia, and narratives [32,33]. For example, ESRI Story Maps, an NGST application, has diverse functions and structures to represent the processes of diverse geospatial issues, including fieldwork, journey, migration, and historical geographic phenomena that Google Earth or ArcGIS do not specialize in. This merit of the NGSTs can meaningfully complement and improve geography and social studies teaching. Therefore, several geography education researchers have focused on the educational potential of NGSTs. For example, Egiebor and Foster [33] developed a Story Maps-based social studies teaching program focusing on the historical geographic contexts and processes of the Trail of Tears. Lee [32] reported that PGTs’ engagement in the representation of South Korean places, regions, and landscapes in narrative formats using Story Maps meaningfully encouraged their contextual and procedural understanding of South Korean regional geography and geographic knowledge.

The term “narrative-based virtual technologies” is a kind of virtual fieldwork using NGSTs or narrative-based platforms. Fieldwork and geography are closely related to narratives; thus, NVF possibly has its characteristic significance. Most of all, diverse processes of geographic features and phenomenographic production and changes in territories have narrative properties [22,34,35]. The attempt to represent the Trail of Tears in a narrative format [33], mentioned above, supports this importance of narratives in geography education.

Moreover, the processes and experiences of fieldwork themselves are also a kind of narrative. More specifically, several fieldwork and travel narratives written by Marco Polo, Johan Wolfgang von Göthe, Alexander von Humboldt, Ferdinand von Richthothofen, and Isabella Bird Bishop are great geographic literature based on fieldwork and travel experiences that have significantly contributed to the development of geography [12,19,36]. Fieldwork participants’ own fieldwork experiences also compose their own geographical or geospatial narratives [10,18]. For example, Savin-Baden and van Niekerk [7] stated that students’ own narratives of their fieldwork possibly facilitate their geographic inquiry and communication based on their fieldwork activities. This is not exceptional in virtual fieldwork. Virtual fieldwork should also be approached from the narrative perspective. Mukherjee [18] attempted to integrate cultural geography virtual fieldwork using Story Maps to encourage students to effectively experience and represent sociocultural and subjective contexts. Go and Lee [27] developed a literature NVF program using Story Maps to encourage preservice Korean language teachers to virtually experience, perceive, and reconsider the geographic and environmental contexts of Korean literature and authors.

In these respects, NVF has potential for PGTE. NVF may facilitate PGTs’ contextual engagement in virtual fieldwork, procedural and contextual understanding of virtual fieldwork activities, and knowhow of preparing and conducting fieldwork. Studies carried out by Lee [32] and Go and Lee [27] show some examples of the meaning of NVF for PGTE. Lee [32] found that NGST-based regional geography education for PGTs encouraged their procedural, contextual, and in-depth understanding of places, regions, and regional geographic features thanks to their self-directed narrative approach toward virtual geospaces represented by the NGST. In addition, Go and Lee [27] reported that preservice Korean language teachers could develop the confidence and knowhow to design and prepare literature fieldwork as they engaged in literature NVF. These two studies suggest that NVF can be a potential alternative for PGTE and fieldwork for PGTs. More particularly, NVF probably encourages PGTs to engage in virtual fieldwork and geography learning more effectively. Furthermore, NVF may improve PGTs’ procedural and contextual insights into fieldwork. Of course, these merits of NVF in PGTE may lead to better virtual and even real fieldwork education in geography classes.

In sum, the integration of narrative and virtual fieldwork, NVF, probably encourages and enhances virtual fieldwork in geography classes and PGTE. Focusing on PGTE, NVF probably encourages PGTs’ engagement in virtual fieldwork activities and their contextual and procedural approaches toward their virtual fieldwork activities [32]. This is why NVF should be approached in the field of PGTE.

3. Research Design

3.1. Participants

The participating PGTs in this study were 28 juniors and seniors of a university in South Korea, drawing on the sampling principles of phenomenographic studies to determine a manageable and sufficient size for the saturation point (generally regarded as 10–30 participants) [15,37]. All participants were students in the travel geography course held in the fall semester of 2019. Among the participants, 23 PGTs were male (9 seniors and 14 juniors), and 5 PGTs were female (3 seniors and 2 juniors). The two youngest PGTs were 21 years old, and the oldest PGT was 27 years old.

3.2. Research Questions

This study focused on the merits and potential of NVF for PGTE. In this respect, this study emphasized the NVF-specific potential rather than the generic merits of virtual fieldwork. Based on this consideration, this study developed two research questions (RQs) to conduct phenomenography-based research: (1) What is the specific potential of NVF, distinguished from non-NVF, such as virtual fieldwork using Google Earth, for PGTE? (2) Why and how does the NVF cultivate PGTs’ understanding of fieldwork in geography classes as PGTs?

3.3. A Narrative-Based Virtual Fieldwork Program Focusing on Travel Geography

The NVF activities were the assignment of the travel geography course. In other words, the topic of the virtual fieldwork of this study was traveling. Of course, travel geography has become one of the subjects of the geography national curriculum in South Korea since the announcement of the 2015 Revision of the 7th National Curriculum [38], which is why the author’s university has established travel geography curricula.

Nevertheless, there are more important reasons why this study focused on virtual fieldwork with travel topics. First, travel and fieldwork quietly share common ground because they are common activities based on direct experiences of places, land surfaces, or fields. In fact, travel has been an effective education method to improve students’ experiences, knowledge, and understanding of various regions and places since the classic era, and the travel of the precursors of modern geography, such as Alexander von Humboldt, was the root of modern geographic knowledge and fieldwork [6]. Second, travel experiences or activities are particularly important in travel geography classes because the main topic of the class is travel. Nevertheless, it is difficult for travel geography classes to conduct real travel or fieldwork due to time and budget limits. This possibly leads to the problem of “a travel geography class lacks travel”. In this respect, virtual fieldwork can meaningfully complement the class by enabling the participating PGTs to engage in traveling or fieldwork in the virtual world. Third, travel is strongly related to narrative. Most of all, travel itself has quiet narrative properties and characteristics, as travel narratives written by famous and great writers including Marco Polo, Johan Wolfgang von Göthe, Alexander von Humboldt, Washington Irving, and Isabella Bird Bishop imply [12,17,36]. Moreover, narratives and stories can encourage traveling. More specifically, the literature that narrates places or landscapes usually fosters traveling to those places, such as Washington Irving’s Tales of the Alhambra, which made the Alhambra in Andalusia, Spain, a globally famous travel destination [39].

The travel geography class was a 15-week course. The textbook was a book on travel geography titled A Geographer’s Humanities Traveling [40]. Of the 15 weeks, the 8th and 15th weeks were middle and final examinations, respectively. Weeks 1 to 6 and weeks 9 to 13 were lectures using the textbook. The 7th- and 14th-week contents created the participating PGTs’ own NVF with travel topics using Story Maps. This study adopted Story Maps as the NVF application because it was the representative narrative-based geospatial technology widely used in diverse fields, including education, due to its merits, including high accessibility, convenience of use, powerful performance and functions, and free online application [13,32,41]. The topic of the 7th-week activity was domestic travel, and the theme of the 14th-week activity was foreign travel. The participants wrote reflective journals on the changes in or refinement of their understanding of NVF using MS Word after completing their NVF assignments. The participating PGTs uploaded their NVF assignments and reflective journals to the learning management system (LMS) of the university.

3.4. Data Collection

The data were collected from the PGTs’ reflective journals. Written texts such as reflective journals are one of the major data collection methods for qualitative research studies [42]. Each journal was written in Korean and approximately 1–2 pages long. The data were analyzed by phenomenography.

3.5. Phenomenographical Data Analysis

Phenomenography is one of the qualitative research methodologies specializing in interpreting and analyzing subjective experiences and learnings: this is the main difference between phenomenology, a qualitative methodology focusing on natural and lived interpretation of a phenomenon, and phenomenography [15,37,43]. This study adopted phenomenography as the research method because it is particularly appropriate for interpreting and analyzing participating PGTs’ learning and experiences with story map-based education [32,33,37,44].

Among diverse phenomenographical data analysis models such as a five-step model [44], this study adopted the seven-step model because it is regarded as a robust data analysis method model widely used in phenomenological studies [14,23]. The seven steps are as follows: (1) familiarization (reading through the raw data and familiarizing with them), (2) compilation (identifying important elements in the raw data by deducing similar and different features from them), (3) condensation (organizing fragmented elements into larger units based on their similarities or relations), (4) grouping (developing preliminary categories based on the results of the condensation step), (5) articulating (reviewing and revising the preliminary categories to confirm the categorization), (6) labeling (denominating categories to represent their core meanings), and (7) contrasting (making theoretical discussions by contrasting the categories).

To grasp the overall structure and contents of the raw data, the author read them carefully more than three times (familiarization step). The raw data were analyzed by NVivo 12 Pro, computer-aided qualitative data analysis software, to code meaningful nodes and to categorize them (compilation, condensation, and grouping steps). The categories were reviewed, reconsidered, and refined to draw theoretical themes to find answers for the RQs (articulating and labeling steps). The author attempted to construct academic discussions on the meaning and potential of travel and Story Maps for (PGTE) based on those themes (contrasting step) (see Figure 1).

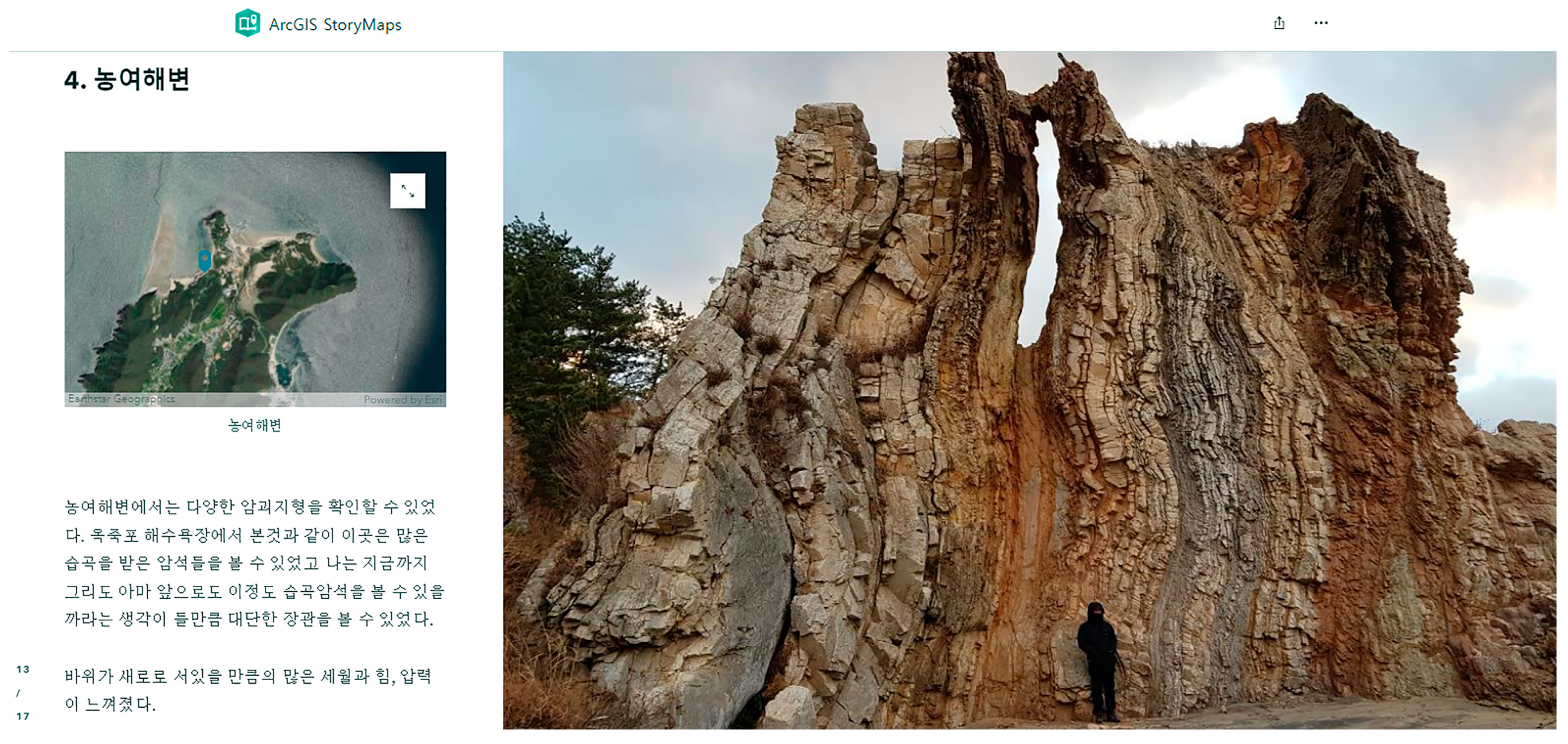

Figure 1.

An example of the Story Maps-based NVF created by one of the participating PGTs. This was based on the PGT’s physical geography fieldwork travel to Daecheong-do Island, located in the Yellow Sea. This page shows his fieldwork story from the Nongyeo Coast, located on the northernmost part of the island. The left sidecar includes the satellite map of the coast and his fieldwork narrative, and the photograph on the right shows his figure standing before a topographic feature of the coast. (English translation for the Korean texts on the left sidecar: “4. Nongyeo Coast. (Caption of the satellite map: “Nongyeo Coast”) I could find various boulder-dominated landforms. I saw several folded rocks on this coast as well as on the Ukjukpo Coast. The Nongyeo Coast provided me impressive landscapes consisted of folded rocks and landforms. I felt massive time and power that made the rock stand vertically.)

4. Results

This study extracted a total of 225 nodes from the data (the familiarization and compilation steps) and classified five tier 1 categories, considering the relations and similarities between the nodes (the condensation, grouping, and articulating steps). Among the tier 1 categories, three were classified as RQ 1 themes, while the other two tier 1 categories were matched to the RQ 2 themes to find discussions on the potential of NVF in PGTE (the labeling and contrasting steps). More detailed explanations on the themes considering the RQs are in Table 1 and the following subchapters.

Table 1.

Classifications, definitions, and examples of the themes.

4.1. RQ 1. What Is the Specific Potential of Narrative-Based Virtual Fieldwork for Preservice Geography Teacher Education?

The participating PGTs answered that Story Maps had particular merit in designing and preparing the contextual processes of the fieldwork. They pointed out that this was due to the characteristics of the Story Maps that integrated the GST and narrative. The PGTs stated that the narrative properties of Story Maps significantly helped them vividly understand and represent the concrete processes and procedures of the fieldwork: they pointed out that this was the characteristic merit of the Story Maps-based NVF toward other kinds of virtual fieldwork using Google Earth or VR facilities. This led to changes in their perspectives toward virtual fieldwork as highly realistic “virtual” fieldwork rather than virtually designed fieldwork maps or plans.

“I had already engaged in virtual fieldwork using Google Earth and QGIS. Of course, those works were impressive, and I could begin to consider the possibilities of virtual fieldwork in geography education. Nevertheless, my travel geography virtual fieldwork using Story Maps meaningfully changed my consideration of virtual fieldwork. Most of all, Story Maps enabled me to represent not only geographic courses or environments but also concrete stories, processes, and experiences of my virtual fieldwork. Thanks to Story Maps specialized in the geospatial representation of narrative, I could engage in much more fieldwork-like or travel-like, rather than map-like or plan-like, travel geography virtual fieldwork.”(Male, senior, 25 years old)

The participants’ engagement in NVF activities also mentioned that NVF has merit in enabling them to intuitively appreciate the whole process and context of fieldwork. According to them, the integration of visually represented fieldwork courses and places and detailed fieldwork narratives was particularly helpful for intuitively perceiving and reviewing the detailed processes, storylines, and meanings of the fieldwork. They considered that this merit of Story Maps-based NVF is particularly appropriate for preparing more meaningful and systematic fieldwork and reviewing and assessing fieldwork activities.

“My travel geography virtual fieldwork topic was my travel to Gunsan City, Jeollabuk-do Province, South Korea. My Gunsan trip, taken last year, is my precious and unforgettable memory. By the way, the trip became somewhat more than a precious memory as I reconstruct and represent it on the Story Maps. As I review my travel memory using both visual representation and narrative structure, I could approach the trip as a detailed geospatial story intuitively rather than mere quitely an abstract “precious thing…”. In this respect, I believe that Story Maps is meritful for preparing and reviewing traveling and fieldwork.”(Female, junior, 22 years old)

In addition, the PGTs also argued that they could engage in quietly personalized virtual fieldwork using Story Maps. They pointed out that Story Maps-based NVF meaningfully encouraged them to reflect on their experiences, memories, identities, wishes, yearnings, and hopes for their travel geography virtual fieldwork in narrative formats.

“It was quietly enjoyable for me to design my virtual fieldwork program under the topic of the trip to Norway. Because I am willing to visit Norway and experience the famous Northern Light Festival in Tromsø. It is very difficult for me to visit Norway due to several limits. I was feeling that I saw fantastic aurora in Tromsø when I created my Norway travel geography virtual fieldwork using Story Maps. It was not a mere assignment because I could virtually conduct my wish list travel story in the virtual world. Moreover, I could learn geographic features of Northern Europe efficiently as I collect data to design my Wishlist into a travel geography virtual fieldtrip.”(Male, senior, 26 years old)

4.2. RQ 2. Why and How Does the NVF Cultivate PGTs’ Understanding of Fieldwork in Geography Classes as PGTs?

The participating PGTs answered that their engagement in the NVF activities meaningfully changed or improved their consideration of the value and potential of virtual fieldwork. More specifically, the narrative property of the NVF made the PGTs significantly consider the importance and usefulness of narratives in virtual and even real fieldwork. The participants began to see the narrative as a significant and meaningful factor of virtual and even real fieldwork education that could encourage students’ active participation and immersion in virtual fieldwork based on their experiences of Story Maps-based NVF activities.

“I was interested in using Google Earth, QGIS, and mobile devices in geography to teach geography. I already used technologies to prepare my department fieldwork. These experiences provided me with the opportunity to consider the possibilities and usefulness of virtual fieldwork. Nevertheless, my interests in and understanding of fieldwork education have noticeably changed thanks to Story Maps. Now I have become to understand narrative as one of the significant factors of virtual fieldwork and real fieldwork. I will positively use Story Maps and make efforts to adopt students’ own or meaningful stories in virtual and real fieldwork when I become a geography teacher.”(Male, junior, 23 years old)

Of course, the participating PGTs also mentioned some limits of the Story Maps-based NVF. The limits included relatively less powerful express maps for visualizing and representing geospatial environments compared to Google Earth or VR facilities and some minor functional issues. They also pointed out that the consideration and complement of these limits probably improve the potential of NVF.

“I appreciate the potential of Story Maps that enable me and students to integrate diverse stories and virtual fieldwork. Nevertheless, I think Story Maps-based virtual fieldwork is not perfect. Although it integrated not only narratives and virtual fieldwork but also diverse multimedia, its express map is not as highly realistic as Google Earth or VR. Therefore, I believe that adopting these applications or platforms to NVE is necessary.”(Male, senior, 26 years old)

In addition, the PGTs’ experiences of and engagement in the Story Maps-based NVF provided them with concrete insights into the methods and directions to complement the limits that impede fieldwork education in geography classes. They were aware that NVF could improve the quality and status of virtual fieldwork in geography classes thanks to its potential to effectively integrate narrative and virtual fieldwork. They could also find methods of travel-like travel geography teaching or adopting travel to geography and virtual fieldwork education as they engaged in travel-themed NVF activities.

“Newly established travel geography is an interesting and promising subject, but conducting real travel is quietly difficult in high school in spite of the critical significance of traveling in travel geography subject. In this respect, virtual fieldwork using Story Maps is particularly meaningful for travel geography teaching in class because it enables not only visual representation but also the geospatial representation of travel stories. In addition, I believe that integration of Story Maps or travel stories themselves and virtual fieldwork possibly improve the quality of travel geography teaching and implement the adoption of travel and fieldwork in geography education in real geography class environments.”(Female, junior, 22 years old)

5. Discussions and Conclusions

The results of this study show that NVF using Story Maps has several merits and potential for preparing and conducting virtual fieldwork in PGTE. First, NVF using NGSTs may encourage PGTs to engage in procedural and contextual virtual fieldwork intuitively due to the technologies’ specific merit of integrating GST and narrative, as the categories 1 and 2 suggest (→RQ 1). Second, NVF is effective for encouraging PGTs’ immersion in and participation in fieldwork activities because it can connect their own experiences or stories and interesting, contextual, and well-organized narratives to virtual fieldwork, as the categories 2 and 3 imply (→RQ 1). Third, the PGTs’ engagement in NVF possibly encourages their understanding of and insights into fieldwork education in geography classes, as the categories 4 and 5 show (→RQ 2). More specifically, the PGTs began to be aware of methods and directions for effectively complementing and implementing virtual and even real fieldwork in geography classes and adopting fieldwork and traveling to geography teaching thanks to the narrative properties of the NVF.

The results of this study provide some discussion on NVF and PGTE. First, NVF is a potential method to complement and implement fieldwork education for PGTE. This implies that the potential, methods, and even limits of NVF should be seriously approached and illuminated in the field of PGTE. PGTs’ active and positive engagement in NVF activities possibly improves their understanding of fieldwork, geography subject knowledge, and knowhow on virtual and real fieldwork education in geography classes. Second, the results of this study show the importance and potential of narratives in fieldwork for PGTE and geography education. Therefore, narrative should be noted as a significant factor of virtual and even real fieldwork. Continuous theoretical approaches toward NVF and adopting narratives of virtual and real fieldwork probably contribute to the betterment of fieldwork education in PGTE and geography education.

Finally, this study suggests the necessity of follow-up research considering the limitations of this study. First, integrating narrative and virtual fieldwork is not restricted to NGST-based activities. Narrative can be integrated with nonnarrative-based GSTs or VRs. In this sense, follow-up studies need to focus on the integration of narrative and various virtual fieldwork platforms. Second, this study was based on travel geography classes for PGTs. Travel is closely related to fieldwork, but fieldwork is not restricted to traveling or travel geography. Follow-up studies should approach other NVF subjects, including topography, urban structure, and changes in territories and borderlines. Third, this study used Story Maps to conduct the NVF. Story Maps is a widely used NGST platform, but it is not the sole and absolute tool for NVF. There are other kinds of NGSTs, and Story Maps is not necessarily superior to them despite its possibilities and usefulness [38]. Moreover, non-NGST platforms and applications such as VR technologies also have possibilities for use in NVF. In this sense, further studies need to illuminate the potential of other technologies and NGST applications in NVF for PGTE and geography education. Fourth, NVF or virtual geography teaching for PGTs probably improves their in-depth and contextual understanding of foreign cultures, languages, and place names. This study did not seriously consider this issue. Follow-up studies focusing on this potential of NVF and virtual geography teaching may contribute to the improvement in fieldwork and geography education for PGTs and even K-12 students.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Catholic Kwandong University (CKU-19-02-0109, approved on 25 September 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Friess, D.A.; Oliver, G.J.H.; Quak, M.S.Y.; Lau, A.Y.A. Incorporating “virtual” and “real world” field trips into introductory geography modules. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2016, 40, 546–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granshaw, F.; Haas, D. Virtual fieldwork in geoscience teacher education: Issues, techniques, and models. In Google Earth and Virtual Visualizations of Geoscience Education and Research; Whitmeyer, S.J., Bailey, J.E., de Paor, D.G., Ornduff, T., Eds.; The Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2012; pp. 285–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ida, Y. The continuity of geography learning contents in Japan. J. Geogr. Res. 2013, 59, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Huh, S. Participant fieldwork experience with versus without data collection in field. J. Korean Assoc. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2018, 26, 99–120. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H.; Leydon, J.; Wincentak, J. Fieldwork in geography education: Defining or declining? The state of fieldwork in Canadian undergraduate geography programs. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2017, 41, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathewson, K. Between “in camp” and “out of bounds”: Nots of the history of fieldwork in American geography. Geogr. Rev. 2001, 91, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin-Baden, M.; van Niekerk, L. Narrative inquiry: Theory and practice. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2007, 31, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubehikov, O. Negotiating critical geographies through a “feel-trip”: Experiential, affective and critical learning in engaged fieldwork. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2015, 39, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, M. “It was amazing to see our projects com to life!” Developing affective learning during geography fieldwork through tropophilia. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2017, 41, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlemper, M.B.; Stewart, V.C.; Shetty, S.; Czajkowski, K. Including students’ geographies in geography education: Spatial narratives, citizen mapping, and social justice. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 2018, 46, 603–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, K.E.; Mauchline, A.L.; Park, J.R.; Whalley, W.B.; France, D. Enhancing fieldwork learning with technology: Practitioner’s perspectives. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2013, 37, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, A.S. Lines of Geography in Latin American Narrative: National Territory, National Literature; Palgrave Macmilan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Treves, R.; Mansell, D.; France, D. Student authored atlas tours (story maps) as geography assignments. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, C.; Ståhle, Y.; Geijer, L. What’s in a grade? Teacher candidates’ experiences of grading in higher education: A phenomenographic study. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zydziunaite, V.; Kaminskiene, L.; Jurgile, V. Teachers’ abstracted conceptualizations of their way in experiencing the leadership in the classroom: Transferring knowledge, expanding learning capacity, and creating knowledge. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karowka, A.R. Field trips as valuable learning experiences in geography courses. J. Geogr. 2012, 111, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMorrow, J. Using a web-based resource to prepare students for fieldwork: Evaluating the Dark Peak virtual tour. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2005, 29, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, F. Exploring cultural geography field course using story maps. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2019, 43, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerski, J.J. Interpreting Our World: 100 Discoveries That Revolutionized Geography; ABC-Clio: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, D.; Miller, S.; Bull, E. Using virtual reality (VR) for teaching and learning in geography: Fieldwork, analytical skills, and employability. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2022, 46, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, D.; Xu, H. Engaging students in learning the relations of geographical elements through GIS-enabled property price visualization. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, P.N. Teaching, learning, and exploring the geography of North America with virtual globes and geovisual narratives. J. Geogr. 2022, 121, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firomumwe, T. Exploring the opportunities of virtual fieldwork in teaching geography during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Geogr. Geogr. Educ. 2022, 45, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojteková, J.; Žoncová, M.; Tirpáková, A.; Vojtek, M. Evaluation of story maps by future teachers. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2022, 46, 360–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Mecca, M. Fieldwork from desktop: Webdoc for teaching in the time of pandemic. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauselt, P.; Helzer, J. Integration of geospatial science in teacher education. J. Geogr. 2012, 111, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, J.-H.; Lee, D.-M. A study on the potential of the reading education using narrative-based geospatial technologies for teacher education: Focusing on the Story Maps-based online reading-travelling. J. Learn.-Cent. Curric. Instr. 2021, 21, 109–124. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M. Teacher education training for geography teachers in Australia. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2004, 13, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhäuserová, V.; Havelková, L.; Hátlová, K.; Hanus, M. The limits of GIS implementation in education: A systematic review. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, I.; Hong, J.-E. Effect of learning GIS on spatial concept understanding. J. Geogr. 2020, 119, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerski, J.J.; Demerci, A.; Milson, A.J. The global landscape of GIS in secondary education. J. Geogr. 2013, 112, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-M. Cultivating preservice geography teachers’ awareness of geography using Story Maps. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2020, 44, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egiebor, E.E.; Foster, E.J. Students’ perceptions of their engagement using GIS-Story Maps. J. Geogr. 2019, 118, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatout, S. Toward a bio-territorial conception of power: Territory, population, and environmental narratives in Palestine and Israel. Political Geogr. 2006, 25, 601–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthanna, A.; Almahfali, M.; Haider, A. The interactions of war impacts on education: Experiences of school teachers and learners. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Clark, S. Isabella Bird, Victorian globalism, and Unbeaten Tracks. Stud. Travel Writ. 2017, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigwell, K. Phenomenography: An approach to research into geography education. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2006, 30, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Current status of curriculum implementation of travel geography in high school based on a survey for teachers. J. Korean Assoc. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2020, 28, 17–35. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saglia, D. Imag(in)ing Iberia: Landscape Annuals and multimedia narratives of the Spanish journey in British romanticism. J. Iber. Lat. Am. Stud. 2006, 12, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.M. Geographer’s Humanities Travel Geography; Analogue: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Caquard, S.; Dimitrovas, S. Story Maps & Co. The State of the Art of Online Narrative Cartography. Mappe Monde 2017, 121. Available online: http://mappemonde.mgm.fr/121_as1/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Stenfors-Hayes, T.; Hult, H.; Dahlgren, M.A. A phenomenographic approach to research in medical education. Med. Educ. 2013, 47, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, F. Phenomenography: A research approach to investigating different understandings of reality. In Qualitative Research in Education: Focus and Method; Sherman, R.R., Webb, R.B., Eds.; RoutledgeFalmer: London, UK, 2005; pp. 140–160. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzáles, C. What do university teachers think eLearning is good for in their teaching? Stud. High. Educ. 2010, 11, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).