Abstract

(1) Background: The literature shows a general lack of sexual knowledge and appropriate sexual health education in persons with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). Moreover, the existing interventions mainly target the neurotypical population, without addressing the specific needs of individuals with ASD. (2) Aims: The current systematic review aimed at analyzing the literature encompassing psycho-educational interventions on sexuality addressed exclusively to people with ASD, in order to report the good practices and to describe the effectiveness of the existing programs. (3) Methods: The systematic review followed the PRISMA-P method. The literature search was conducted in June 2022, examining PsycInfo, PsycArticle, PubMed, and Education Source. The search strategy generated 550 articles, of which 22 duplicates were removed, 510 papers were excluded for not matching the criteria, and 18 articles were finally included. (4) Results: Ten papers presented good practices and eight focused on intervention validation. The analysis showed that the good practices were essentially applied in the intervention studies. No intervention proved to be successful both in increasing psychosexual knowledge and in promoting appropriate sexual behaviors; thus, further research is needed. (5) Conclusions: The current review allows for critical reflection on the need for validated sexuality interventions.

1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder with a multifactorial and heterogeneous etiology, encompassing a series of neurodiverse conditions whose onset occurs in the early years of life. People with ASD show qualitative impairments in social interactions and communication and a stereotyped, limited, and repetitive repertoire of interests and activities [1]. Currently, ASD is considered one of the most widespread developmental disabilities, with an incidence of 1 in 44 children in the United States [2]. As for Europe, a recent study carried out by Autism Spectrum Disorders in Europe (ASDEU) on the prevalence of ASD in the European Union estimated that approximately 1 in 89 children would be autistic [3].

In recent years, several studies have been conducted on the neglected topic of sexuality of people with ASD. Sexuality is a complex phenomenon characterized by different desires, thoughts, fantasies, attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, practices, values, roles, and relationships and it represents an essential component of our identity as human beings [4]. Therefore, sexual rights, enshrined by the World Health Organization, must be protected and guaranteed for all, without any discrimination.

Social and cultural changes have modified the way we consider sexuality and affectivity within relationships: the ever-increasing knowledge regarding complex issues such as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), abortion, sexual dysfunctions, and sexual functioning allowed the development of a positive approach to human sexuality [4]. Indeed, nowadays, sex education programs not only aim to address issues such as the use of contraceptive technologies or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancies, but they also incorporate topics related to love, affectivity, and consent [5].

At the same time, an increasing number of studies on sexuality in persons with ASD have been published in the past 10 years. However, there is still a long way to go, as for a long time, the dimension of sexuality has been confined to a secret area for anyone with a disability [6]. Historically, society has considered sexuality in people with disabilities by relating to either of two opposing poles: on the one hand, they were seen as “asexual” or “eternal children”, not desiring or being interested in relationships, and on the other hand, they were regarded as potentially dangerous to others [7]. Until recently, the sexuality of people with developmental disabilities has been ignored and viewed from a blaming perspective, rather than seen as an integral part of everyone [6].

Nevertheless, studies agreed that persons with ASD have pubertal development and physical and sexual maturation that adheres to a similar timeline as individuals with typical development (TD); moreover, they show interest in romantic relationships and engage in sexuality-related behaviors [8,9]. However, the specific information processing associated with ASD—such as peculiarities in communication and social interaction, the possible presence of repetitive patterns of behavior, and inflexibility or difficulty in taking others’ perspectives—may lead to challenges in coping with the cognitive, emotional, and relational changes that occur during adolescence [10,11]. The hyper- or hypo-sensitivity associated with ASD may also favor problems in coping with the physical changes associated with puberty. For instance, girls with ASD may present greater emotional and behavioral issues related to the onset of menstruation [12].

Despite the similar sexual development to that of TD peers and the evidence showcasing the importance of the sexuality dimension for people with ASD, an interesting finding from the literature on the topic is that there is a general lack of sexual knowledge and appropriate sexual health education in this population [13,14]. Another issue is that the main target of existing interventions is the neurotypical population, thus not focusing on the specific social, cognitive, and emotional needs of individuals with ASD. For example, the chronological age of persons with ASD often does not coincide with their cognitive, emotional, and psychosocial development [15]. Additionally, repetitive behavior and a lack of flexibility could interfere with the spontaneity of sexual interactions [16]

The main sex-related problems to which this population is exposed could be partially or totally stemmed by increasing knowledge and developing appropriate skills. This need is also expressed by schools, families, and mental health professionals, who are fundamental components for an effective generalization and internalization of the skills. Indeed, the presence of a supportive environment that provides consistent information is crucial for the stabilization of such skills over time [17]. For this reason, it is essential to act through ongoing training and support towards all figures who have a role of responsibility towards individuals with ASD.

Another aspect that should not be ignored concerns the sources of information about sexuality that these individuals generally consult. The social and relational difficulties faced by people with ASD expose them to a higher risk of learning about sexuality through the passive use of information channels which could provide partial or distorted notions [18]. Failure to acquire correct information about the development of healthy sexuality makes persons with ASD more likely to consider themselves consistent with the negative beliefs conveyed by society [19]. Moreover, this exposes them to a higher risk of engaging in inappropriate sexual behaviors, such as masturbating or denuding themselves in public, touching others inappropriately, or developing paraphilias, which may evolve into problematic behaviors, such as acts of self-harm or aggression [6,20,21]. In their review, [20] emphasized that the development of interventions that educate adolescents with ASD about sexuality and related problems is important to reduce inappropriate sexual behavior and to understand the mechanism behind their occurrence.

The lack or inadequacy of sex education also increases the probability for individuals with ASD to be victims or perpetrators of abusive behaviors [6]. In particular, the risk of sexual victimization in this population is very high, especially among young women [22]. A study conducted in 2014 [18] found that 78% of respondents with ASD reported being exposed to sexual victimization at least once.

In summary, the failure in acquiring psychosexual skills denies people with ASD a crucial developmental opportunity. This emphasizes the importance of developing educational interventions suited to the level of physical and cognitive maturation of the persons with ASD to support them in acquiring knowledge and practices which could be useful for the development of a responsible sexual identity and healthy meaningful relationships [9].

Recently, three reviews have addressed the topic of interventions on sexuality education [23,24,25]. Their main limitation is that they included people with several different disorders or disabilities (ASD, intellectual disability, developmental disabilities). Only a few studies focus specifically on ASD [26,27,28]. Since each disorder has its peculiarities, identifying specific sex education needs in individuals with such a heterogeneous disorder as ASD is paramount [29].

The current systematic review expands the current knowledge about the psycho-educational interventions on sexuality, offering an integrated view on the topic. We pursue this goal adopting two strategies: focusing exclusively on people with ASD and including articles about best practices to allow for a comparison with evidence-based interventions. The aims of the study are (1) reporting the good practices, arising from the literature in the field, to adopt when structuring sexuality education interventions; (2) describing the existing sex education programs only targeting persons with ASD; (3) checking the congruence between the good practices reported by the literature and the actual features of the interventions that were conducted; and (4) analyzing the effectiveness of the interventions for psychosexual education.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted by B.R., D.B., and M.C. following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P; [30]).

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Only studies targeting adolescents and adults diagnosed with ASD, with or without comorbidities, were considered eligible. Studies conducted on both people with ASD and people with other diagnosis were excluded when the data referring to the sub-sample of people with ASD were not clearly identifiable.

A further inclusion criterion was the focus on sex education interventions and their validation, strategies, and recommendations for the development of sex education treatments and treatment of problematic sexual behaviors. Only articles published in peer-reviewed journals were included; dissertations, book reviews, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews were excluded.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

The literature search was conducted on 20 June 2022, examining the following databases: PsycInfo, PsycArticle, PubMed, and Education Source. The following keywords were included: (Autism OR ASD OR Autism Spectrum Disorder OR Asperger’s OR Asperger’s syndrome OR Autistic Disorder OR Aspergers) AND (sexuality education OR sex education OR sexual health education) AND (interventions OR strategies OR best practices OR treatment OR therapy OR program OR management).

2.3. Data Management and Selection Process

The search strategy generated 550 articles, and 22 duplicates were removed. Each remaining paper was assigned a unique identifier throughout the process.

In the screening stage, B.R. excluded all irrelevant articles based on the title and the abstract of the 528 studies. A total of 499 papers were excluded for not matching the criteria due to the following reasons: mismatched or mixed groups in the sample, and out of scope (e.g., studies conducted with people with ASD but not related to sexual education). Moreover, 3 studies were not retrievable.

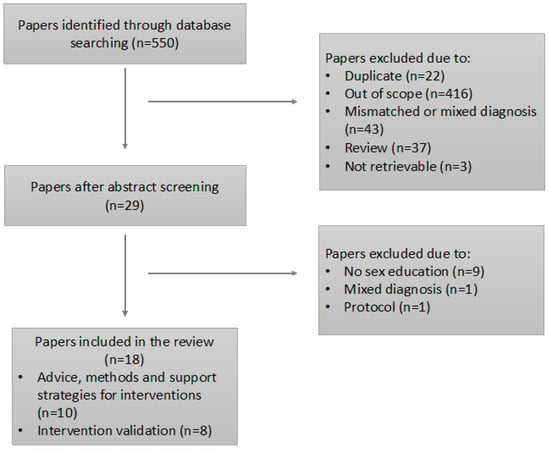

The eligibility phase was based on reading the content of each article by B.R. and D.B. The interrater agreement was good (Cohen’s K = 0.85); the disagreements were solved by discussing them together with M.C. A total of 11 articles were excluded because they analyzed the topic of sexuality without addressing sex education, included a mixed diagnosis sample (and this was not specified in the abstract), or consisted of a study protocol. At the end of the process, 18 articles were included, as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search results and filtering process.

2.4. Data Collection Process

B.R. filled out a piloting form developed ad hoc for this review, to extract relevant data from the selected papers. D.B. and M.C. revised the form; disagreements among the authors were discussed and solved.

2.5. Data Items and Outcomes

We summarized the content of the included articles into four tables.

Table 1 addresses the advice for sexual interventions and Table 2 reports methods and support strategies for sexual interventions. Table 1 and Table 2 include the following variables: author/s, year of the publication and the country where the study was run; the objective of the study; informants in the study; persons targeted by the intervention; intervention topics; mode of intervention delivery; instructor/s; methods and support strategies for the intervention; usefulness of strategies for sexuality education.

Table 1.

Advice for sexual interventions reported in the studies.

Table 2.

Methods and support strategies for sexual interventions reported in the studies.

Table 3 and Table 4 report information extracted from the intervention studies on sexual education. Table 3 includes the following variables: author/s, year of the publication and the country where the study was run; details concerning the participants (number, gender, age, and IQ); inclusion criteria to participate in the study; how recruitment of participants took place; study aim/s; gathered measures. Finally, Table 4 includes the following variables: program name and length; study design; information concerning the study procedure and/or the type of intervention; person targeted by the intervention and role of parents; main study outcomes; details concerning follow-up (if it was conducted and, if so, when it was conducted and if improvements recorded at post-test lasted at follow-up).

Table 3.

Summary of extracted data from intervention studies addressing sexuality education in ASD individuals: participants’ details and study aim and design.

Table 4.

Summary of extracted data from intervention studies addressing sexuality education in ASD individuals: intervention details, procedure, and outcomes.

3. Results

The analysis included 18 papers that were published between 1983 and 2022 (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). The interest in the topic of sexuality education and intervention specifically addressed to people with ASD is quite recent, as 17 out of 18 papers were published from 2008. The past literature, in fact, mainly referred to persons with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities, including participants with heterogeneous diagnoses. The articles were drafted by authors from the USA and Europe.

The studies had different “objectives”, “informants”, and “targeted person”. The first group of papers reported advice, methods, and support strategies for interventions (10 studies, years of publication: 1983–2022; Table 1 and Table 2). Three studies collected information directly from persons with ASD [34,35,40], two articles discussed the point of view of parents or educators [36,39], and five papers reported the perspective of scholars, trainers, or researchers in the field [31,32,33,37,38]. According to the selection process, all the papers concerned advice, methods, and support strategies specifically meant for persons with ASD. They were addressed to adolescents or young people, except for one study [35] which included persons up to 61 years of age. One study was specifically designed for girls [39].

Regarding ”intervention topics“, the following were identified: biological and reproductive area (e.g., anatomy and physiology, puberty, gender differences, pregnancy, and birth control); health and hygiene (e.g., body care, health and wellness, body and disease, STDs/HIV prevention, masturbation, and menstruation); relationships (e.g., social skills, different kinds of relationships, friendships and intimacy, interpersonal behavior, feelings, and expression, dating, marriage and parenting, sexual orientation, sexual language, and unspoken rules); self-protection/self-advocacy (e.g., sexuality as a positive aspect of self, sense of self, self-esteem and self-worth, personal rights, diversity in sexual desires, inclusion of alternative intimate relationship structures and sexualities, appropriate/inappropriate touching, appropriate/inappropriate public/private behaviors, decision making, personal boundaries, protection against abuse, saying “no” to nonconsensual sex and high-risk behaviors, sexual discrimination), issues related to the use of technology (e.g., social navigation).

For what concerns “mode of intervention delivery”, all the ten studies analyzed in Table 1 emphasize the importance of developing interventions that should be tailored and individualized, as interventions should consider the great heterogeneity within the group of individuals with ASD. In particular, 2 of the 10 studies support the need for a thorough assessment of both the children with ASD and their developmental context [34,38]. One study specifically stresses not to forget the impact of culture on attitudes when planning an educational program [34]. Moreover, four papers support the idea that sex education should be an ongoing process through the life course that begins early on, especially for basic skills, so that individuals with ASD can acquire habits and information related to how to maintain good health as early as possible [31,34,35,39].

Four studies emphasize the importance of adopting a perspective toward sexuality education aimed at generalizing skills potentially relevant in multiple contexts [31,32,36,37]. Related to this, during the skill acquisition process, it is important to involve all those who take care of people with ASD: experts should promote consistency and collaborative work among families, schools, and mental health professionals. To this end, four studies reported that one of the main goals should be creating a supportive environment that provides information consistent with those promoted by professionals [31,33,37,39]. This is a key aspect for retaining the competencies acquired by individuals with ASD. Besides of the consideration of the broader context, three papers emphasize that the involvement of people with ASD themselves should not be forgotten [32,34,35].

Next, five studies suggest different ways of presenting contents related to sexual education to people with ASD [32,34,36,39]. The most suitable educational formats might be those using direct, clear, and simple teaching methods that provide information in an interactive and deferred manner. It seems important to communicate information explicitly using examples and normalizing differences among individuals. Moreover, the use of visual materials, such as pictures or photographs associated with the most appropriate behaviors, has been suggested to be the most effective one. In addition, people with ASD can be given lists containing various steps that enable them to cope with the most complicated situations. In this case, pictures of typical social situations can be used to raise awareness about their emotions and to enact the most appropriate behaviors. Many papers stress the importance of using various techniques and strategies, but not all of them turn out to be easily accessible. In fact, two studies emphasize the importance of considering the issues of cost and access [36,39].

Finally, five studies support the use of evidence-based strategies and the need for a more in-depth and specific evaluation of the effectiveness of the intervention strategies used for sex education [32,33,36,37,40].

Two further studies suggest using an evaluative procedure to provide parents with feedback concerning their offspring’s skills and to possibly revise the strategies used for sexuality education [32,36].

Regarding the main “instructor/s” for delivering an intervention to people with ASD, four out of the 10 relevant studies emphasize the primary role of parents in educating their children on sexual health [31,33,36,39]. In fact, families should be involved in planning and implementing sociosexual curricula, as they are primary sources of information for every individual and are likely to produce lasting changes in their offspring. Nevertheless, families might require some extra support, such as dedicated healthcare professionals and schools with specifically trained staff. ASD experts could be valuable resources for parents, and their presence can promote consistency and foster collaborative work. One study also shows that interventions should be co-facilitated by both a neurotypical adult serving as a role model and an autistic adult in which individuals with ASD can mirror themselves [40]. This study also suggests that the intervention should take place online to include a wide range of different participation styles, should include people of all genders, and should explicitly use a neurodiversity model as the basis for the content.

Regarding Table 2, we sought to identify the main “methods and support strategies” used to convey psychosexual information to people with ASD, and their “usefulness”. To this end, we analyzed 6 of the 10 studies already reported in Table 1. Of these, four studies recommend the use of Social Stories to prepare individuals for puberty-related changes or to help them find solutions to difficult situations already occurred [32,33,37,39]. Two studies support the idea that ABA-based intervention strategies could be successful in sexuality education to promote greater skill acquisition and reduction in unwanted behavior related to sexuality [33,37]. Two studies suggest the use of electronic/IT-based strategies (e.g., videos, video games, websites, mobile device applications) that offer the greatest potential for the engagement of people with ASD thanks to a compelling visual display, the possibility of simulating social environments, and a high rate of interactivity [36,39]. Finally, two studies propose for girls only the use of visual calendars for menstruation [34,39]. Other useful methods include life-sized dolls for the concept of public/private body parts; vibrating watches or smartwatches for menstruation-related hygiene; visual strips for teaching skills in a sequence; “my touching rules” and “circle of intimacy” for topics and situations related with “touch and personal safety”; “relationship circle” to visually indicate different kinds of relationships; photos and life-story work to help building a sense of self; and Social Behavior Mapping to understand the impact and the motivation behind an inappropriate sexual behavior.

The second group of eight studies reported the description and the effectiveness of the selected interventions (eight studies, years of publication: 2012–2021; Table 3 and Table 4). The studies were conducted in a limited number of “countries”: four were run in the USA [41,43,44,46], two in The Netherlands [42,45], one in Greece [48], and one in the Republic of North Macedonia [47]. Overall, the “participants” taking part in the intervention studies listed in Table 3 were 324, ranging from 9 to 19 years of age.

The intellectual level of participants was above borderline cognitive functioning (i.e., IQ ≥ 70) in three studies [42,45,46], not specified in four studies [41,43,44,47], and low in the remaining study [48]. All the participants were diagnosed with ASD before the beginning of the study or as an inclusion criterion to be enrolled in the study. In some cases, a prior diagnosis was made; in others, it was confirmed by a clinical psychologist, or additional tests/interviews were administered in order to determine ASD severity. Comorbidity with other conditions was not declared in the studies; therefore, we could not report on this potentially interesting variable.

“Inclusion criteria” to participate in the interventions widely varied across the studies, mainly due to specific study aims (see Table 3 for details).

“Recruitment of participants” was conducted in different ways across the studies, i.e., through children’s hospitals [46], children’s schools [47], nonprofit organizations [44], parent groups [41], through internet postings [43], or within the context of large mental health care organizations [42,45]. One study (in which there was only one participant) did not report information concerning recruitment [48].

The “study aims” overall encompassed the willingness to test the effectiveness of the specific intervention conducted. The effectiveness of the intervention, in turn, was determined in different ways by the authors. In some cases, participants’ knowledge of specific concepts (for example related to puberty) was evaluated before and after the intervention; in other cases, parents were asked if they noticed an improvement in their offspring’s behavior or if they spotted an application by their children of the taught concepts. Other studies aimed at testing the feasibility/acceptance of specific interventions delivered to ASD individuals with particular features. Another study aimed at decreasing socially unacceptable forms of sexual behavior and had the further aim of assessing generalization effects of the intervention to new contexts. Moreover, half of the studies also aimed at checking whether the acquired knowledge and skills were maintained at the follow-up.

Due to the heterogeneity of the studies, the “measures” used in each research are different and reflect the specific aims of the researchers. Multiple measures can be found in each study. Informants could be parents and/or trainers and/or children/adolescents themselves. Moreover, different types of tools were adopted: questionnaires, scales, interviews, tests, inventories, surveys, and observations. Those tools could be already existing or adapted from existing ones or created ad hoc.

The content of Table 4 aims at systematizing specific information from the included studies that are useful to understand which features likely favored the effectiveness of the intervention.

As far as the study design is concerned, most studies adopted a non-experimental “design”, in that a control group was not included (see Table 4). The nature of the design did not prevent the authors from conducting pre- and post-test phases of the research. Nonetheless, only two studies [45,46] managed to employ an experimental approach. These two studies randomly allocated participants either to the intervention or to the control group, and both groups were composed of participants with similar characteristics (age, diagnosis, and intellectual functioning).

The “length” of the whole program varied between two and nine months. Regarding the “procedure/type of intervention”, the number and frequency of the intervention sessions considerably varied among the studies. Specifically, between 3 and 35 sessions were implemented, which could have a daily/weekly/bimonthly frequency and could last between five minutes and two hours. In most of the studies, individual sessions were organized [41,42,45,47,48]; two studies adopted group sessions only [43,44], and one study used both individual and group format [46].

In six out of eight studies, the intervention was led by a professional [42,43,44,45,47,48]. In one study, the intervention was conducted by both a professional and the mothers of the participants as co-trainers [41]; in another study, the intervention group was partly guided by a trainer and partly self-guided [46]. Interventions took place in different settings: at home when targeting private behaviors (i.e., masturbation or menstruation) or when self-guided [41,48], or at school/autism centers/local library when required by the protocol or in case of group sessions [43,44,45,47]. The setting was not specified in two studies adopting the same program [42,45].

The main topics addressed within the training sessions were biological and reproductive functions related to puberty; sexual health and personal hygiene; skills needed for building and maintaining healthy romantic and amicable relationships; self-protection/self-advocacy regarding sex and intimacy; and the safe use of technology to acquire correct information regarding sexuality.

Among the strategies used in the intervention studies, the following can be found: stories, leaflets, worksheets, illustrations, and videos. All of these strategies share these common features: they contain clear and concise descriptions, direct and explicit instructions, step-by-step concrete explanations, and massive use of visual and realistic materials. Moreover, in most cases, interactive use of the materials was promoted.

In the totality of the studies, both adolescents and their parents were the “person targeted by the interventions”. Nonetheless, the “role of parents” could vary. In some studies, parents were informed about their offspring’s improvements and new acquisitions to enhance generalization and ensure consistency [42,44,45,47,48]; in other studies, parents took an active part in interventions for learning new strategies to adequately support their children’s achievements [43,46]. In one last study, mothers played a co-trainer role [41].

To evaluate the effectiveness of the programs, “outcomes” such as changes observable in youth/parents, and feasibility and acceptability of the program were taken into account. Particularly, changes in youth can be grouped into cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Specific tools were indeed used to assess their knowledge and understanding of concepts regarding sexuality, to measure changes in their sexually related behaviors (in terms of increase in appropriate behaviors and decrease in inappropriate ones), generalization of acquired knowledge, and behaviors to new contexts and therapists. Changes in parents can be identified with reference to their satisfaction with the program, improvement in communication with their children, and a decrease in their concerns related to their children’s inappropriate sexual behaviors (and their negative consequences). Moreover, a specific set of outcomes concern the feasibility and acceptability of the program, which were investigated by asking for feedback from youth and parents on the activities, gathering parental satisfaction, and comparing different conditions (looking at specific parameters such as the completion rate of the program).

As many aspects were examined by each study, it is not possible to state whether a specific intervention was more effective than another. In fact, each study showed strengths in addressing some issues but limitations in addressing other issues. Moreover, it must be noted that the generalizability of results is hampered by the specific features of each sample (such as number and age of participants, diagnosis and level of intellectual functioning, sample composition, degree of parental involvement, intervention setting and modality, length and frequency of sessions).

Finally, regarding “follow-up”, this was conducted in half of the studies. The results of the follow-up phase were gathered within different time frames: in two interventions after a short time (i.e., after three/five weeks and after one month; 44, 48); in the other two after a long time (i.e., after one year; 41, 45). Positive outcomes were always maintained at follow-up, except in one study, in which the second follow-up showed that the improvements did not last.

4. Discussion

The current systematic review had four main aims. The first and the second aims were reporting the good practices regarding a structured sexuality education intervention, and describing the intervention on psychosexual education targeting youth with ASD. The contributions analyzed in this systematic review addressed the need that arose from the larger literature about psychosexual education for persons with and without disabilities reported in the introduction: filling the lack of sexual knowledge and appropriate sexual health education is crucial to protect persons with ASD from internalizing negative stereotypes promoted by society regarding their sexuality [19], and to reduce the risk of engaging in inappropriate sexual behaviors, developing paraphilias, or being victims or perpetrators of abusive behavior [6,20,21]. Interestingly, a shift in perspective is observable comparing the literature published in with the contributions.

A third aim was addressed in the current systematic review: checking the congruence between the literature suggesting recommendations for sexuality interventions (10 papers) and the features of the actual interventions that we retrieved (8 papers). The analysis showed that the recommendations were essentially included in the intervention studies.

One recommendation was to involve all those who take care of people with ASD and three papers emphasized that people with ASD themselves should serve as trainers. Indeed, in the totality of the intervention studies, both adolescents and their parents took part in the programs; usually, the intervention was led by a professional and none of the studies reported the engagement of instructors with ASD. Parents’ involvement was usually explained to support individuals with ASD to better generalize the new acquisitions.

The literature suggesting recommendations also stressed that sex education should be an ongoing process and should start as early as possible. In six intervention studies out of eight, children were involved at a starting the age of 9–12 years, the longest program duration was nine months, and parents were usually involved, probably to try and guarantee a long-lasting effect and consistency of the provided information.

The intervention topics suggested in the recommendation literature were actually covered by the programs: biological and reproductive functions related to puberty; sexual health and personal hygiene; skills needed for building and maintaining healthy romantic and amicable relationships; self-protection/self-advocacy regarding sex and intimacy; safe use of technology to acquire correct information regarding sexuality.

All of the advice studies also emphasize the importance of developing tailored and individualized interventions—indeed, six programs included individual sessions.

Concerning the teaching methods, the interventions shared common features strictly related to enhancing the chance of effective learning in people with ASD, thanks to the use of clear and concise descriptions, direct and explicit instructions, step-by-step concrete explanations, and visual and realistic materials; the interactive use of the materials was also a common technique.

The fourth aim concerned the effectiveness of the programs on psychosexual education. Overall, no intervention proved to be successful both in increasing psychosexual knowledge and in promoting appropriate sexual behaviors (and/or reducing inappropriate ones). Notably, only one study obtained acceptable results both in cognitive and behavioral aspects. Nonetheless, this was a single case study, and behavioral improvements did not last in the long term.

On the positive side, it must be acknowledged that seven out of eight studies did show cognitive improvements in the involved subjects right after the intervention. Of these, three studies even showed maintenance of such positive outcomes at follow-up. One study was not successful in that adolescents’ knowledge did not increase significantly between pre- and post-test. However, the authors attributed this result to methodological shortcomings (i.e., questions were too easy to detect differences in post-test).

Looking at the positive long-term consequences detected in half of the studies—at least on a cognitive level—the pattern of results could suggest that the program structure of all these studies was effective. Nonetheless, only one of these studies implemented a rigorous methodology (RCT experimental design), which also had the largest sample. Therefore, when planning a psychosexual intervention with ASD adolescents, nowadays professionals should try and follow the structure of this program (Tackling Teenage Training Program, TTT). Specifically, TTT has a quite long global duration and requires an intensive commitment by participants and their parents. Indeed, participants are engaged in individual 1-hour sessions on a weekly basis, covering several topics through the use of different kinds of structured exercises. Importantly, this program entails a main role of a specifically trained professional, with longstanding and certified expertise and experience in the field. Parents join the intervention not as co-trainers, but as scaffolders and facilitators in promoting consistency with the training, in order to favor the generalization of acquired knowledge/competencies and stimulate communication with their offspring. Moreover, the results of this successful study highlighted that the younger participants benefited more from the intervention, suggesting the importance of planning timely trainings that begin as soon as possible and that cover the whole life span.

Limitations and Future Directions

In this section, we discuss the main limitations concerning the intervention studies included in the current systematic review. The limitations are described together with indications for future research.

The first limitation is that the number of studies meeting the inclusion criteria was scant and the number of participants in all but two studies was below 30. This hampers the generalizability of the results, especially considering the limited number of countries in which the studies were conducted. Moreover, there was a high prevalence of male participants (258 out of 324), that on the one hand reflects the higher prevalence of ASD in the population but, on the other hand, might lead to a neglect of young girls’ psychosexual needs and issues. It is known that girls on the spectrum receive a delayed diagnosis or do not receive it at all [49]. This calls for further efforts in planning tailored interventions specifically addressing female needs.

Another important shortcoming that we faced in analyzing the included studies was the marked heterogeneity in participants’ intellectual functioning or the lack of this crucial information (missing in half of the studies). Future research should carefully consider this parameter together with the potential comorbidities in order to develop appropriate training.

A further limitation concerns the methodology of the interventions: as highlighted in Section 3, only two of them had an experimental/RCT design and only half of the studies planned a follow-up phase. The lack of a control group affects the validity of the interventions and speaks to the fragility of the results reported in the studies. Researchers interested in advancing our knowledge of evidence-based interventions should pay specific attention to the study design by including a control group and possibly adopting an RCT approach.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review contributes to the literature by analyzing the topic of sexuality education and the psychosexual interventions specifically addressed to people with ASD, and by showing at which conditions such interventions are effective. Sexuality education programs should be early, tailored, and easily translatable in practice to better address the needs along the autistic spectrum. In line with recent trends in the field of research with and for persons with disabilities, the interventions should be informed by autistic people themselves in order to hear and take into account their own voice. Moreover, long-term maintenance of positive outcomes is warranted by interventions realized by expert professionals (trained ad hoc and constantly supervised), coupled with specific strategies/indications provided to parents so that they can efficiently support their children. Furthermore, our analysis highlighted the lack of evidence-based strategies and instruments that are sensitive enough to detect behavioral changes, which are the desired outcomes of every intervention. To conclude, this contribution allows for critical reflection on the need for validated interventions that can help people with ASD to acquire useful skills and appropriate sexual behavior to experience sexuality and relationships positively and healthily.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B. and B.R.; methodology, B.R., D.B. and M.C.; formal analysis, B.R., D.B. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, B.R., D.B. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, B.R., D.B. and M.C.; visualization, B.R., D.B. and M.C.; supervision, D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Data & Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Bougeard, C.; Picarel-Blanchot, F.; Schmid, R.; Campbell, R.; Buitelaar, J. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Co-Morbidities in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 744709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Defining Sexual Health: Report of a Technical Consultation on Sexual Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- UNESCO. International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education. An Evidence-Informed Approach; UNESCO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, K.E. Sexuality and Severe Autism; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 9780857006660. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, N.; Young, P.C. Sexuality in Children and Adolescents with Disabilities. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2005, 47, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheak-Zamora, N.C.; Teti, M.; Maurer-Batjer, A.; O’Connor, K.V.; Randolph, J.K. Sexual and Relationship Interest, Knowledge, and Experiences among Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 2605–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewinter, J.; Van Parys, H.; Vermeiren, R.; van Nieuwenhuizen, C. Adolescent Boys with an Autism Spectrum Disorder and Their Experience of Sexuality: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Autism 2017, 21, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, G.I.P.; Stokes, M.A.; Mesibov, G.B. Socio-Sexual Functioning in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Existing Literature. Autism Res. 2017, 10, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecora, L.A.; Mesibov, G.B.; Stokes, M.A. Sexuality in High-Functioning Autism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 3519–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, R.; Crane, L.; Mairi Roy, E.; Remington, A.; Pellicano, E. “Life Is Much More Difficult to Manage during Periods”: Autistic Experiences of Menstruation. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 4287–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginevra, M.C.; Nota, L.; Stokes, M.A. The Differential Effects of Autism and Down’s Syndrome on Sexual Behavior. Autism Res. 2016, 9, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehzabin, P.; Stokes, M.A. Self-Assessed Sexuality in Young Adults with High-Functioning Autism. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2011, 5, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballan, M. Parents as Sexuality Educators for Their Children with Developmental Disabilities. Siecus Rep. 2001, 29, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Urbano, M.R.; Hartmann, K.; Deutsch, S.I.; Polychronopoulos, B.; Dorbin, V. Relationships, Sexuality, and Intimacy in Autism Spectrum Disorders. In Recent Advances in Autism Spectrum Disorders; Fitzgerald, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, K.; Urbano, M.R.; Raffaele, C.T.; Qualls, L.R.; Williams, T.V.; Warren, C.; Kreiser, N.L.; Elkins, D.E.; Deutsch, S.I. Sexuality in the Autism Spectrum Study (SASS): Reports from Young Adults and Parents. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 3638–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Lavoie, S.M.; Viecili, M.A.; Weiss, J.A. Sexual Knowledge and Victimization in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 2185–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, M.S. Becoming Sexually Able: Education to Help Youth with Disabilities. Siecus Rep. 2001, 29, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Beddows, N.; Brooks, R. Inappropriate Sexual Behaviour in Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: What Education Is Recommended and Why. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2015, 10, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellemans, H.; Colson, K.; Verbraeken, C.; Vermeiren, R.; Deboutte, D. Sexual Behavior in High-Functioning Male Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2007, 37, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazalis, F.; Reyes, E.; Leduc, S.; Gourion, D. Evidence That Nine Autistic Women out of Ten Have Been Victims of Sexual Violence. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 852203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, G.; Hooley, M.; Attwood, T.; Mesibov, G.B.; Stokes, M.A. Autism and Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review of Sexuality and Relationship Education. Sex. Disabil. 2019, 37, 353–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.K.; Brown, C.; Darragh, A. Scoping Review of Sexual Health Education Interventions for Adolescents and Young Adults with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 2020, 38, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strnadová, I.; Danker, J.; Carter, A. Scoping Review on Sex Education for High School-Aged Students with Intellectual Disability And/or on the Autism Spectrum: Parents’, Teachers’ and Students’ Perspectives, Attitudes and Experiences. Sex Educ. 2022, 22, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chianese, A.A.; Jackson, S.Z.; Souders, M.C. Psychosexual Knowledge and Education in Autism Spectrum Disorder Individuals. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2021, 33, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, K.; Bussières, E.-L.; Poulin, M.-H. Développement Harmonieux de La Sexualité Chez Les Jeunes Ayant Un TSA: Revue Systématique et Méta-Analyse Des Pratiques Favorables. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2022, 63, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A.; Caterino, L.C. Addressing the Sexuality and Sex Education of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Educ. Treat. Child. 2008, 31, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, L.A.; Stagg, S.D. Experiences of Sex Education and Sexual Awareness in Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 3678–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and Explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesibov, G.B.; Schopler, E. The Development of Community-Based Programs for Autistic Adolescents. Child. Health Care 1983, 12, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnai, B.; Wolfe, P.S. Social Stories for Sexuality Education for Persons with Autism/Pervasive Developmental Disorder. Sex. Disabil. 2008, 26, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, P.S.; Condo, B.; Hardaway, E. Sociosexuality Education for Persons with Autism Spectrum Disorders Using Principles of Applied Behavior Analysis. TEACHING Except. Child. 2009, 42, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatton, S.; Tector, A. Sexuality and Relationship Education for Young People with Autistic Spectrum Disorder: Curriculum Change and Staff Support. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2010, 37, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.P.; Maticka-Tyndale, E. Qualitative Exploration of Sexual Experiences among Adults on the Autism Spectrum: Implications for Sex Education. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2015, 47, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackin, M.L.; Loew, N.; Gonzalez, A.; Tykol, H.; Christensen, T. Parent Perceptions of Sexual Education Needs for Their Children with Autism. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 31, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballan, M.S.; Freyer, M.B. Autism Spectrum Disorder, Adolescence, and Sexuality Education: Suggested Interventions for Mental Health Professionals. Sex. Disabil. 2017, 35, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clionsky, L.N.; N’Zi, A.M. Addressing Sexual Acting out Behaviors with Adolescents on the Autism Spectrum. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, C.; Pellicano, E.; Crane, L. Supporting Minimally Verbal Autistic Girls with Intellectual Disabilities through Puberty: Perspectives of Parents and Educators. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 2439–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, E.F.; Graham Holmes, L. Using Formative Research to Develop HEARTS: A Curriculum-Based Healthy Relationships Promoting Intervention for Individuals on the Autism Spectrum. Autism 2022, 26, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klett, L.S.; Turan, Y. Generalized Effects of Social Stories with Task Analysis for Teaching Menstrual Care to Three Young Girls with Autism. Sex. Disabil. 2012, 30, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, L.P.; van Visser, K.; Tick, N.; Boudesteijn, F.; Verhulst, F.C.; Maras, A.; Greaves-Lord, K. Improving Psychosexual Knowledge in Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Pilot of the Tackling Teenage Training Program. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 1532–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, L.L.; Fox, S.A.; Christodulu, K.V.; Worlock, J.A. Providing Education on Sexuality and Relationships to Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Their Parents. Sex. Disabil. 2016, 34, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pask, L.; Hughes, T.L.; Sutton, L.R. Sexual Knowledge Acquisition and Retention for Individuals with Autism. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 4, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, K.; Greaves-Lord, K.; Tick, N.T.; Verhulst, F.C.; Maras, A.; van der Vegt, E.J. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Examine the Effects of the Tackling Teenage Psychosexual Training Program for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, C.E.; Ratto, A.B.; Granader, Y.; Dudley, K.M.; Bowen, A.; Baker, C.; Anthony, L.G. Feasibility and Preliminary Efficacy of a Parent-Mediated Sexual Education Curriculum for Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Autism 2020, 24, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankova, T.; Trajkovski, V. Sexual Education of Persons with Autistic Spectrum Disorders: Use of the Technique: ‘Social Stories. Sex. Disabil. 2021, 39, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkogkos, G.; Staveri, M.; Galanis, P.; Gena, A. Sexual Education: A Case Study of an Adolescent with a Diagnosis of Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified and Intellectual Disability. Sex. Disabil. 2021, 39, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood Estrin, G.; Milner, V.; Spain, D.; Happé, F.; Colvert, E. Barriers to Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis for Young Women and Girls: A Systematic Review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 8, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).