1. Introduction

In South Africa, as in other countries, the pursuit of improvements in education quality has been characterized by the focus on improving learning and teaching approaches. South Africa has made a commitment to accelerate development over the next seven years through the South African National Development Plan 2030 [

1] and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal Declaration [

2]. Meeting this challenge depends fundamentally on the ability of the South African education system to equip today’s children for high levels of achievement and active participation in a global 21st century society and economy [

3]. In this context, to train talents with comprehensive competencies, many educational institutions have increasingly adopted student-centered learning methods as the core learning and teaching approach for curriculum design. In this context, project-based learning (PBL), as a widely used learner-centered approach, is described as a method of learning and teaching that engages students in gaining professional knowledge whilst acquiring essential skills and competencies structured around complex, authentic and open-ended problems and projects [

4].

The notion of PBL has been variously defined and applied at different levels [

5]. In this context, we define PBL as a systemic practice in which it has been adopted as the core learning method in the curriculum design and students conduct self-directed learning through working on problems in teams [

4]. Implementing PBL at the institutional level demands the restructuring of classroom practices to challenge teachers’ traditional roles by expecting them to facilitate independent and collaborative learning [

6], which also encourages teachers to change their traditional teaching roles and follow a constructivist learning approach. The teacher’s understanding and acceptance of, as well as adjustment to, this new role is crucial for the adoption of new instructional approaches such as PBL [

6,

7]. However, teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning are not always easy to change [

8]. Thus, it is important to provide teachers with pedagogical training activities to help them better understand pedagogical theories, develop professional and pedagogical competencies, reflect on their teaching practices and thereby better adapt to PBL methods [

9].

The study took place in a private K-12 school context, specifically in an educational institution named N school, where a PBL curriculum has been adopted for six years. At N school, newly joined teachers, regardless of their previous teaching experience, undergo diverse pedagogical training on PBL. This includes learning about PBL, practicing PBL methods, working collaboratively on curriculum mapping to forge interdisciplinary teaching and conducting classroom observation of teachers with more PBL experience. In addition, all teachers are expected to participate in professional development activities relevant to PBL. In order to better facilitate teachers’ transformation of their pedagogical beliefs regarding PBL, this study explores the pedagogical beliefs that they hold—constructivism-based beliefs or traditional beliefs—when working in a PBL context and how they perceive their roles as teachers. The findings of this research may generate new knowledge on teacher beliefs in South Africa and support suggestions for the adoption of PBL across the K12 schooling system.

2. Theories and Literature

Teacher belief has long been the focus of educational research. It can be broadly defined as the tacit and often unconsciously held assumptions about students, learning, classrooms and the academic material to be taught [

10]. Philosophers of education understand belief as a proposition that is accepted as true and a way to explain relationships between factors, such as a task, an action, an event and an individual’s attitude toward it [

11]. Calderhead proposed five main components of teacher belief: beliefs about learners and learning, teaching, the curriculum, learning to teach and the self and the nature of teaching [

12]. Other researchers pointed out that teacher beliefs are related to teaching efficacy, teacher academic expectations and teacher goal orientation [

13]. Breen et al. understand teacher beliefs as a system that includes what teachers should teach (content), how they should teach (approach) and what responsibility they have (roles) [

14]. The last two points are the focus of this study. The beliefs that teachers hold can directly impact their thoughts, instructional decisions, utilization of teaching methods and current teaching practices, thereby influencing students’ beliefs, learning experiences and learning outcomes [

15]. Prior studies have also pointed out that teacher beliefs are context-bound and related to teachers’ previous learning and teaching experiences and interactions with students [

16,

17]. Other studies have framed teacher beliefs to include beliefs about themselves, the context or environment, the content or knowledge, specific teaching practices, teaching approaches and students [

18].

As a comprehensive concept, teacher belief encompasses a variety of aspects of knowledge, learning culture and attitudes to students and to themselves (e.g., motivation, self-efficacy, identity and sense of agency), ranging from traditional beliefs to constructivist beliefs. In traditional teaching beliefs, teachers are regarded as the center of learning and the source of knowledge; responsible for making choices for students; valuing the control of class; and using summative assessment methods (e.g., quizzes and exams) [

18,

19]. In constructivist theory, students become less dependent on teachers and texts for answers and more reliant on the content knowledge that they acquire through personal research and their own judgment, whereby teachers need to transfer from traditional teaching roles to the roles of facilitators. In this context, teachers are expected to hold constructivist beliefs, which involve students’ perspectives in the processes of developing the curriculum, choosing learning content and evaluating work [

20,

21,

22]. Based on the emphasis on the learner and the learning process, active learning methods (e.g., PBL and teamwork) and formative assessment methods (e.g., peer assessment) are usually adopted in constructivist learning [

17]. In constructivist theories of learning, on the one hand, students bring beliefs to teachers and education programs that significantly influence learning content and learning approaches. Teacher beliefs could influence teachers’ self-efficacy for student engagement and classroom management, thereby influencing students’ learning outcomes [

13]. On the other hand, teachers’ beliefs play a role in changing educational processes [

8,

23].

Prior studies have shown that pedagogical beliefs serve as important drivers for teachers’ approaches to the implementation of innovative learning methods [

24,

25]. This is evident particularly when conducting instructional innovation, such as implementing PBL at the curriculum level, and changing teachers’ roles and beliefs from traditional teaching to constructivist learning is an essential step since teachers’ beliefs frame their teaching strategies and shape their teaching behavior and practice. Teachers’ constructivist learning beliefs align well with PBL as it places emphasis on the learner’s ownership of ideas and personal interpretation of knowledge. Teachers who hold the belief that PBL promotes student learning are reported to be more adaptable to PBL and have higher motivation to learn pedagogical theories and practice PBL [

24,

26]. As mentioned above, teacher belief is not static, but fluid and changing, based on teachers’ experience and interactions with students. However, it is not an easy task to change teachers’ beliefs [

8], especially in a situation where educational changes are promoted from the top down. To promote the educational change from traditional learning to PBL and to impact teacher beliefs, attention must be paid to designing pedagogical training activities and programs to support teachers’ professional development and investigate the effectiveness of this training in terms of changing participants’ teacher beliefs [

27].

Although several studies have examined and compared teachers’ traditional teaching beliefs with constructivist beliefs in diverse learning contents [

16,

28], there has been little research on teachers’ beliefs and practices in the context of the change from traditional approaches to constructivist approaches in South Africa, where PBL remains a new approach. Several researchers have reported South African pre-service science teachers’ beliefs related to teacher-centered teaching and student-centered learning [

29,

30], focusing on students who will become teachers instead of in-service teachers. Ramnarain and Hlatswayo have reported teachers’ positive beliefs and attitudes toward implementing enquiry-based learning in a rural school in South Africa [

31]. However, in addition to studying teachers’ favorable attitudes towards new learning approaches, further exploration is needed to broaden our understanding of the way in which teachers hold teaching beliefs, how they understand their roles and how their beliefs influence their teaching practice.

To meet these needs, the present study explored the pedagogical beliefs held by teachers in a PBL school in South Africa. In particular, the study was guided by the following research questions:

- (1)

In which ways do teachers hold traditional versus constructivism-based beliefs?

- (2)

Do teachers’ pedagogical beliefs vary based on their teaching experiences?

- (3)

Which particular roles do teachers feel they take, particularly in a post-pandemic context?

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context and Participants

This study was conducted in a private school in South Africa known as N school. The school, which began operations in 2017, has enrolled over 1300 students from pre-school to Grade 12 and employs 95 teachers. Compared to most South African schools, which still follow a traditional approach to learning and teaching, N school adopted PBL as an active learning method because it enables students’ development of comprehensive competences and continuous learning of various subjects through working on real-life problems, developing possible solutions and presenting their work using technological tools. The learning model adopted by N school for K-12 education includes the following principles: (1) taking a teacher-facilitated, learner-orientated approach to learning; (2) using enquiry and project-based learning over an extended period of time to facilitate and develop learners’ knowledge and skills; and (3) developing processes and guidelines to facilitate the implementation of the approach.

Strategies such as the use of English as the language of learning and teaching, the inclusion of indigenous learning systems and the incorporation of technology from the Foundation Phase (FP) onward have been adopted, with the aim of helping students develop the knowledge and skills required in the rapidly changing, technological era while remaining grounded in, and proud of, their African heritage. Moreover, through experiencing teamwork in PBL, students are expected to develop diverse generic skills in communication, negotiation skills, conflict-solving and collaboration.

This K-12 educational institution has implemented PBL at the curriculum level over the past six years and provided in-service pedagogical training courses on PBL professional development for teachers. Professional development at N school mainly takes the form of teacher workshops, which are provided to all teachers and are broken down into school grades, phases and individual subjects. The objective of PBL professional development is to introduce newly joined teachers to PBL and train them on PBL learning objectives, outcomes, teaching practices and assessment tools. These teachers are exposed to PBL learning and teaching strategies and tactics to train them and build their skills and competencies in subject integration, classroom management and assessment. Newly joined teachers are allocated mentors (called Critical Friends), who guide them through the PBL teaching processes and practices. N school also conducts continuing professional development for all its teachers on a regular basis, mainly in the form of workshops.

This present study was an initial explorative phase of an ongoing Ph.D. project conducted by the first author. The first author played a dual role in this research, being one of the board members for the school ownership and being a researcher aiming to conduct a research-based approach to school development. Although the first author was not involved in the daily practice since the school’s daily practice is conducted by a campus school management team (SMT) consisting of school principals and academic coordinators, there was an awareness of any potential bias. With awareness of such bias, careful considerations of ethics have been taken in the current study. First of all, the present study, as well as the whole Ph.D. project plan, has received institutional ethical approval from the Danish university with which the first three authors are affiliated (the same institution where the Ph.D. project is registered). The process of this study strictly followed internationally recognized ethical principles and European data protection regulations which are adopted by the university. The research plan was approved by the school management during which process the first author was not involved. The actual data collection was processed by the school management team, which has commented on and approved the study. A consent letter to participate in the study was sent to all teachers at N school. It was clearly stated in the consent letter that the ultimate goal of the study would be for school improvement and the outcomes would only serve for research purposes but no other purpose, such as teaching evaluation or appraisal.

In addition, during the study, the participants are not identified by name and only demographic data regarding their years and experience as teachers and the number of years as teachers at N-school was collected. This ensures anonymity and protects the participants from any undue influence. A voluntary-basis survey was sent to 95 teachers at N school via email in the 2022 academic year. A total of 83 teachers completed the questionnaire, representing an 87% participation rate, which underlines the voluntary nature of participation in this study.

The participants included teachers with diverse teaching experience at the school, including newly joined teachers without professional PBL training experience, teachers who had joined the school in the past 12 months and had experienced professional development in PBL for a limited period and teachers who had been with the school for one to five years and had been exposed to PBL professional development for a longer period. Detailed participant information is listed in

Table 1.

3.2. Data Collection

An embedded mixed method [

30,

31,

32] was adopted as the research method in this study. This method enables researchers to collect both quantitative and qualitative data for different but related research questions in a single study [

30]. A survey study was conducted, which included two parts. The first part of the survey collected quantitative data to answer the first two research questions on the ways in which teachers hold traditional beliefs versus constructivism-based beliefs. We adopted an established instrument called the Teacher Belief Survey (TBS) [

19]. This instrument follows a teacher belief framework with four dimensions: Traditional (classroom) Management (TM), Traditional Teaching (TT), Constructivist Teaching (CT) and Constructivist Parental engagement (CP). The first dimension, TM, values teachers’ control of a class and students’ obedience to rules, with teachers being expected to be at the center of learning and to take responsibility for the teaching schedule and learning materials. In the TT dimension, teachers regard textbooks as the best sources for learning, make choices for students and prefer summative evaluation methods such as paper-and-pencil tests. CT emphasizes students’ involvement in developing the curriculum, creating bulletin boards, working collaboratively and evaluating their own performance. The fourth dimension, CP, sees teachers’ roles as involving the formation of a supportive family for students and their parents. On the basis of this framework, a 28-item instrument was designed and tested [

19]. Items in the four dimensions were randomly arranged, with respondents choosing their answers as strongly disagree, disagree, agree and strongly agree (i.e., a 4-point Likert scale). Through measuring the types of teachers’ beliefs, this study also explored whether teachers’ beliefs varied according to their teaching experiences and their exposure to N school’s PBL professional development. The second part of the survey included two open-ended questions to collect qualitative data in order to answer the first research question on teachers’ understanding of their competences and roles, especially during the post-pandemic era. The teachers at N school were therefore asked about the most important characteristics of a good teacher and the new or additional roles that teachers have assumed following the pandemic.

3.3. Data Analysis

For the first part of the survey, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), internal consistency analysis (Cronbach’s alpha), descriptive statistics, a paired sample test, an independent sample test and the Kruskal-Wallis test were conducted. Detailed results are shown in the sections on the validity and reliability of the results. For the section of the survey with two open-ended questions related to teachers’ roles, inductive analysis with open coding was used to analyze and categorize the participants’ beliefs about teachers’ competences and roles. For the first question—“Please list three or more of the most important characteristics of a good teacher nowadays”—three bottom-up themes were summarized: aspects of knowledge about the subject and curriculum, teaching competencies and intrapersonal values. For the second open-ended question, related to teachers’ new roles in the post-pandemic context, patterns such as the greater requirement of digital skills, closer relationships with students and more responsibility for students’ health and well-being were reported.

3.4. Validity and Reliability

3.4.1. Content Validity

Content validity refers to the extent of participants’ understanding of the statements within the survey [

31]. In order to enhance content validity, the researchers in this study conducted a literature review of the frameworks of teachers’ beliefs and related instruments. Based on Woolley et al.’s TBS, items were established through research group discussion and an expert review by inviting four experts in faculty professional development, PBL and engineering education [

17].

3.4.2. Construct Validity

Construct validity is used to examine the extent to which a survey accurately assesses what it is supposed to [

31]. In this study, construct validity for the TBS was checked through EFA and CFA (conducted using SPSS software) of 83 cases to explore the structure of this survey. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value in the EFA was 0.616 and the

p-value of the Bartlett test of sphericity was significant (

p < 0.001). Principal component analysis with an eigenvalue greater than 1.00 was used as the extraction method and Varimax with Kaiser normalization was adopted as the rotation method. The results of the factor loading in the EFA are listed in

Table 2. With a cut-off score of 0.4 for the factor loadings, six items were deleted (TM5, TT4, TT5, TT6, TT10) because they were not loaded on any factors. Twenty-two items were divided into four factors, mainly following the original design. Six items were loaded on factor one (TM); seven items were loaded on factor two (TT); seven were loaded on factor three (CT); the last factor (CP) included three items. Three items, TM6, TT9 and CT4, were multiple-loaded on two factors. Thus, we considered the value of the loading and justified the results based on the content of the item and the logic of theories [

31,

32].

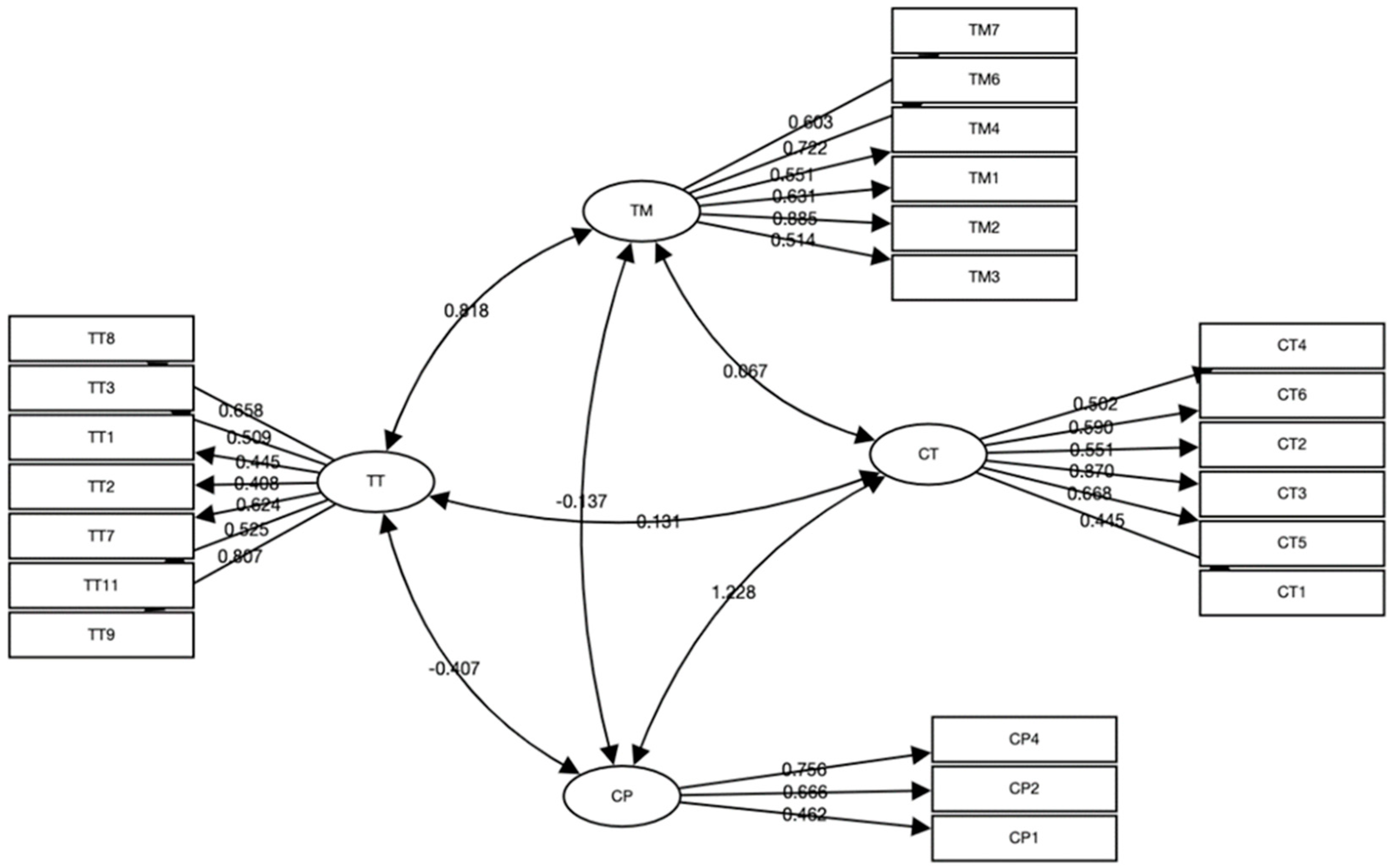

Based on the EFA results, CFA was used to assess cross-loading among the 22 items [

32].

Figure 1 reports the CFA results. Based on the results, items TM6, TT9 and CT4 were justified for loading on the factor with the highest scores. CFA produced statistical results for goodness of fit (df = 203, χ

2 = 326.271, GFI = 0.921, RMSEA = 0.092, CFI = 0.884, AGFI = 0.625). The factor loadings for all factors were significant and exceeded the cut-off score of 0.4, thus supporting the results shown in

Table 2 [

33].

After combining the results of the EFA and CFA, four factors were identified, namely TM, TT, CT and CP, that accounted for 48.9% of the total variance. One limitation of the quantitative data in this study is the small sample size (N = 83); however, this is an acceptable size for factor analysis (N > 50) [

34]. To summarize, the results are in accordance with the original version of the TBS presented in prior studies [

17].

3.4.3. Reliability

We conducted an internal consistency analysis of the survey by calculating Cronbach’s alpha, where a value equal to or greater than 0.6 is considered acceptable [

35]. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the items in general and for each dimension had acceptable values, at 0.749 (TM), 0.733 (TT), 0.727 (CT), 0.680 (CP) and 0.813 (full scale), meaning that the reliability of the survey is good.

3.4.4. Qualitative Data Analysis

For the analysis of open-ended questions, the auditing procedure was conducted through research group discussions on defining, categorizing and revising codes, as well as potential researcher bias. In addition to collaborative correctives, two researchers served as independent coders who coded the same part of the transcripts and discussed the results over two rounds. The inter-rater reliability (IRR) for every theme was over 85% in the second round of coding.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

To answer the first research question—in which ways do teachers hold traditional versus constructivism-based beliefs—the descriptive statistics of the survey results were calculated.

Table 3 shows the resulting means, standard error means and standard deviation of each factor. Factor 3 (CT) showed the highest mean values (mean = 3.241, std. dev = 0.361) of all factors and the factor that received the lowest mean average was TT (mean = 2.705, std. dev = 0.395).

A paired sample t-test was used to compare the means of the four factors. Significant differences were found between five pairs (1, 2, 4, 5, 6), which are shaded in

Table 4.

These results indicate that factor 3 (CT) contributed the most to teachers’ beliefs, followed by factors 1 (TM) and 4 (CP). The factor with the lowest value was TT. There was no significant difference between TT and CP. Moreover, the effect sizes were also calculated to compare the differences between the factors. With Cohen’s d values of more than 0.3, the differences in pair 2 and pair 6 were medium and the differences in pairs 1, 4 and 5 were significant, supporting the results of the paired sample t-test.

4.2. Demographic Variables Analysis

4.2.1. Comparison between Groups with Different Pedagogical Beliefs

To answer the research question of whether teachers’ pedagogical beliefs vary based on their experiences, this study explored the differences between teachers with varying experiences in terms of their pedagogical beliefs and their roles during students’ learning processes. An independent sample test was performed to determine whether there were significant differences between teachers who regarded themselves as Critical Friends or PBL mentors and those who did not. The results in

Table 5 only show a significant difference in the dimension of TT. Compared to teachers acting as Critical Friends or PBL mentors, teachers who did not operate in these two roles indicated firmer belief in TT. No significant difference between the two groups was found for the other dimensions.

4.2.2. Comparison between Groups with Levels of Teaching Experience at N School

This study also explored the differences in teachers’ beliefs between groups with different levels of teaching experience in N school. Due to the small sample size, a Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted instead of an ANOVA [

36]. The results, shown in

Table 6, show no significant difference in the CT and CP dimensions, while new teachers (less than 12 months in N school) were found to have higher levels of belief in TM and TT than teachers with more experience (1–5 years).

4.2.3. Comparison between Groups with Different Levels of General Teaching Experience

By conducting the Kruskal-Wallis test, we also explored the differences between teacher groups with varying levels of general teaching experience (i.e., not just teaching experience at N school), ranging from 0–2 years to more than 20 years. No significant differences were found between teachers with levels of teaching experience for any of the four dimensions, as shown in

Table 7.

4.3. Results from the Open-Ended Questions

The third research question—which particular teaching roles do the teachers themselves believe in, especially in a post-pandemic context—was explored in the survey through open-ended questions. In concrete terms, the participants were asked to list three or more important characteristics of a good teacher in the current post-pandemic context. Using the qualitative analysis software NVivo, we analyzed and categorized the participants’ answers through open coding and inductive methods. The themes and codes that emerged from the qualitative data are described below.

Firstly, three bottom-up themes emerged which relate to the characteristics of good teacher roles: knowledge about the subject and curriculum, teaching competencies and intrapersonal values. Codes under each theme are listed in

Table 8, with their definitions and the number of times they were mentioned by the participants. Within the theme of literacy and knowledge, the pedagogical literacy and knowledge code was mentioned with the highest frequency; this code refers to teachers’ understanding of diverse pedagogical theories and ability to choose appropriate methods for teaching practices. The code with the second-highest frequency was professional literacy and knowledge, which emphasizes teachers’ professional quality in their subjects. Other codes, such as research knowledge and awareness of students’ learning objectives, were also mentioned by the participants. In the second theme, competencies, participants indicated that they regarded innovation, listening skills, adaptability, collaborative skills and lifelong learning as important characteristics for teachers. Teachers’ understanding of their competencies thus includes both constructivist teaching beliefs and traditional teaching beliefs. In terms of interpersonal values and attitudes, the most important characteristics from the participants’ perspectives were open-mindedness and inclusivity; possession of these qualities means that they are open to new experiences and new learning methods and may give students the freedom to explore the unknown and learn from mistakes. The second-highest code in this theme highlighted interpersonal values, such as being passionate, followed by flexibility, patience and being fun. Taking care of students’ emotions, mental health and well-being, being friendly and less authoritarian and showing love to students were also regarded as important characteristics for teachers in the qualitative data, which reflects the concepts of constructivist teaching beliefs. To answer the research questions, various codes were identified in answers to the open-ended question. The codes addressed both constructivism and traditional pedagogical beliefs, such as constructivist beliefs related to teachers’ facilitation skills and their interaction with students as well as the traditional teaching belief in teachers’ authority.

In the second open-ended question, participants were asked about their new roles as teachers in the post-pandemic context, where digital tools and online learning resources have become highly involved in the course design. Three patterns emerged from the participants’ answers. The first new role was as an information technology (IT) specialist who provides online digital and technology support for students. Meanwhile, teachers reported that they had learned how to use new digital tools and improved their IT skills by designing online teaching activities during the lockdowns. The second change was the formation of closer relationships with others during the lockdowns. Many teachers reported that they became close friends with their students or colleagues after sharing their stories, giving advice on their home problems and providing emotional support to each other. Last but not least, participants pointed out that in the COVID-19 era their responsibilities not only involved teaching and learning, but also included supporting students’ physical health, mental health and well-being. On the one hand, teachers took on the role of security guards who enforced safety rules, disinfected the school and managed socially-distanced classrooms. On the other hand, they also become healthcare workers and psychologists who facilitated students’ management of their personal and social lives, helped students stay physically and mentally healthy and provided support to students to prevent panic when there were positive cases at the institution. The terms ‘psychologist’ and ‘health care workers’ were mentioned and used colloquially by participants. Such terms were used as self-perceived, which did not reflect on any officially defined concepts. In the emergent COVID-19 cases, various employees including security guards, administration staff, secretaries and teachers who are not professionally trained as ‘psychologists’ or ‘healthcare workers’ were involved in various forms of COVID-19 protocols including body temperature scanning, sanitizing people and some form of pastoral care and psychosocial support.

While these changes influenced teachers’ beliefs in transferring from traditional perspectives to constructivist teaching and parenting perspectives, they also brought challenges and difficulties, such as longer working hours and heavier workloads. Thus, more attention needs to be paid to teachers’ changing roles and their adaptability in the post-pandemic context.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study used a mixed method to explore the pedagogical beliefs held by teachers in a PBL K-12 school in South Africa. The quantitative part of this study illustrates the ways in which teachers hold traditional versus constructivism-based beliefs and explores whether teachers’ pedagogical beliefs vary based on their levels of experience, while the qualitative part reports teachers’ perspectives on their roles, particularly in a post-pandemic context.

The results of the study fill an existing gap in the literature with evidence of teachers’ diverse beliefs on the subject of the change from traditional teaching approaches to constructivist approaches in South Africa. To answer the first research question, the study adopted and validated the Teacher Belief Survey [

18], using it to identify participants’ pedagogical beliefs across four dimensions—traditional classroom management (TM), traditional teaching (TT), constructivist teaching (CT) and constructivist parental engagement (CP). The participants were found to hold more constructivism-based beliefs than traditional teaching beliefs, which could be due to ongoing pedagogical training for these teachers’ professional development and the top-down implementation of PBL strategies at the curriculum level [

24,

37]. In terms of the second research question—“Do teachers’ pedagogical beliefs vary based on their experiences?”—participants with more years of teaching experience at N school were found to hold fewer traditional teaching beliefs (TM and TT) than newcomers at N school, while no significant differences were found between the participant groups with different years of teaching experience in general (i.e., not just at N school). This result also provides empirical evidence of the effectiveness of pedagogical training. With systemic design of pedagogical training at the institutional level, teachers’ beliefs and practices change over time [

24].

Qualitative analysis of the open-ended questions answered the third research question—“What particular teaching/teacher roles do teachers believe in themselves, especially in a post-pandemic context?” Participants reported their understanding of what a good teacher was according to three characteristics: knowledge about the subject and curriculum, teaching competencies and interpersonal values. Their understanding encompassed both traditional and constructivist teaching beliefs. Some participants still held traditional teaching beliefs that emphasized the teachers’ authority in the classroom and high levels of control [

38], while most participants referred to constructivist teaching beliefs, including their understanding of a student-centered learning environment, willingness to adopt innovative learning approaches and awareness of playing the role of facilitator in students’ collaborative learning processes [

37]. Moreover, participants realized that in the post-pandemic context their roles were not limited to delivering knowledge and skills, but also extended to supporting students’ individual learning processes and well-being. During the lockdowns, many participants realized the need to improve their digital and technology skills and identified the new role of an IT specialist as an important component of teachers’ responsibilities [

39]. Moreover, participants also emphasized the importance of taking on the role of ‘psychologist’ in order to support students’ mental health, well-being and personal growth. On the one hand, the teachers’ roles as ‘healthcare workers’ and ‘psychologists’ encouraged closer relationships between them and their students: the teachers reassured students of their safety, took care of their emotions and asked about their families or friends [

40]. However, on the other hand, teachers faced challenges in providing counseling services to students because of their lack of psychological knowledge and the heavy workload, coupled with anxiety [

40]. Thus, more support is needed from the institutional level, such as mental health services for school staff and students and basic professional training for teachers.

Change in teacher beliefs is a long-term process which requires both effort from the teachers and support from the institutional level. To support the transfer of teachers’ beliefs from traditional to constructivist perspectives, this study suggests that it is important for both teachers and school managers to develop positive attitudes towards constructivism, build on their pedagogical knowledge and understand the characteristics of innovative learning approaches, especially when working in a non-traditional school such as N school. Beliefs are formed and changed by prior experiences and also influence individuals’ future practice. Thus, at the individual level, teachers should be encouraged to participate in learning activities designed to follow the reform initiatives, practice diverse student-centered learning methods in the classroom and share materials and ideas for teaching with colleagues, which will enable them to see the benefits of constructivist learning for student growth and thereby develop more constructivist teaching beliefs [

41,

42].

Organizers and managers of teachers’ professional development training should develop an awareness of the individual differences in belief changes and gaps between beliefs and practices, especially in situations where top-down educational reforms are being implemented. The change process could take a long time and encounter both expected and unexpected challenges. These aspects should be taken into consideration when designing pedagogical training programs.

At the institutional level, it is important to have supportive policies in place to motivate teachers’ implementation of innovative learning approaches and expose teachers to positive experiences of implementing constructivism in their classrooms. Both short-term and long-term professional development activities need to be provided to teachers, such as organizing pedagogical workshops for peer learning and self-reflection, providing individual consultation services, inviting mentors for facilitation and developing pedagogical training certifications. More training experiences enable teachers to learn PBL methods, be involved in successful constructivism implementation practices, communicate with experienced educators and thereby change their teaching beliefs and practices [

24,

41,

42].

This study has several limitations. First, it only explores teachers’ beliefs at a certain time, which limits the evidence it can provide about the fluidity of teachers’ beliefs. Further studies are needed to explore how change may happen with the intervention of professional development and what may support changes in teachers’ pedagogical beliefs. Second, this study mainly reports data gathered through a questionnaire survey, which illustrated a few significant differences between teacher groups with different levels of teaching experience. A more comprehensive picture of teaching experience and related impact factors in a PBL context needs to be explored in the future by means of multiple methods including interviews, observations and longitudinal studies. The third limitation is that this study only focuses on pedagogical beliefs, which may contrast with actual practice. How teachers’ pedagogical beliefs influence their teaching practice in the classroom is a subject that needs further investigation, especially with regard to the comparability of teacher beliefs and teaching practices. Last but not least, due to the tension in the given South African school context, in that many schools were reluctant to adopt new teaching methods such as PBL at an institutional level, the study was only feasible to be conducted in a single institution, which limited the transferability of its current results. The outcome of the explorative study will be further validated through longitudinal studies and multiple methods through the subsequent phases of the ongoing Ph.D. study.

To summarize, the present study contributes to the validation of the Teacher Belief Survey in a South African context and provides an overview of the traditional and constructivist beliefs held by teachers in a South African institution. Mixed method research was conducted by means of the Teacher Belief Survey and open-ended questions. Most participants held student-centered and constructivist beliefs, while some participants still held teacher-centered and traditional beliefs in a K-12 educational institution implementing PBL at the curriculum level. Significant differences were found between teacher groups with different levels of teaching experience in N school. Participants with more experience in pedagogical development training in N school tended to be more open-minded and to make more use of classroom interactions and formative assessment methods. These results indicate that pedagogical training for staff development and supportive policy at the institutional level has a considerable influence on changes in teachers’ beliefs. However, this is still far from changes in teaching practice. More efforts are needed to further explore changes in teachers’ beliefs and the alignment of those beliefs with their teaching practice.