Abstract

Personal learning environments or their acronym PLEs are understood as a set of tools, resources, connections, and activities that each person regularly uses for learning. This study examines the PLE approach in a university setting, evaluating its impact on student learning in a university subject within an education master’s program. The effect is assessed from two perspectives: a quantitative one based on the ‘PLE test’—administered at the beginning and end of the course—and a qualitative one based on the assessment provided by the students themselves regarding the impact of training in digital tools and competencies on their PLE, at the beginning and end of the course. The ‘PLE test’ measures four factors: time organization, creation–editing, searching–investigating, and collaborating–contact networks. In all four factors, by the end of the course, there is a significant increase in usage scores, especially in the last two. The students’ assessments of the evolution of their PLEs reflect the evident impact of this approach as a strategy for more effective and self-managed learning.

1. Introduction

The PLE (personal learning environment) emerges as an educational perspective intrinsic to self-directed learning, as a vision of the present and future of education (learning and teaching). It aims to comprehend and analyze the conditions associated with student autonomy in their learning process [1], and reflects the transition from traditional analog environments with limited resources to digital settings, characterized by the proliferation or ‘infoxication’ of current information [2,3]. PLEs are conceived as a strategy for work and learning that arises from specific personal interests, they are nourished by connections with circles of contacts (friends, acquaintances, and experts, among others) and strengthened with the aid of various available resources. Thus, they constitute spaces and strategies in both the digital and analog domains that individuals employ for their own learning process, which is nourished and developed through a wide spectrum of technological tools [4]. PLEs represent one of the most recent and disruptive approaches in educational technology [5,6,7].

Now is the best time in history for curious individuals or those with something to contribute or share with the world, thanks to the Internet, ICT, and Web 2.0 tools [8]. Here, personal learning environments gain strength as a strategy for accessing knowledge, combining tools, materials, and resources (including human resources) employed for lifelong learning [9,10,11]. In a PLE, the focus of learning is on the individual who seeks to acquire or expand their knowledge, following the line of Jonassen [12] who defined meaningful learning as involving an active, constructive, intentional, authentic, and collaborative approach.

Characteristics such as ubiquitous internet access alongside the proliferation of mobile devices makes learning possible anywhere and at any time, both inside and outside the school. This circumstance, coupled with the creative application of technology, sets the stage for personal learning environments [10].

In this work, the terms PLE ‘environment’ or ‘strategy’ are used interchangeably, understood as a set of actions aimed at learning or perfecting knowledge, initiated by motivation or need, and involving these four elements [8]:

- Use of tools for searching, compiling, and filtering information;

- Search for online and offline resources—journals, blogs, websites, forums, chats, experts;

- Establishment of networks—with individuals, contacts;

- Production of digital objects that are shared.

The perspective offered by PLE is part of the ecology of learning, where the learning conditions, resources and opportunities, formal and informal aspects, and social and technological elements interplay in a digital environment [13].

PLEs focus on the learner, self-directed and autonomous learning principles (heutagogy), self-configuration, and self-management of the learning environment, with DIY (do-it-yourself) as the cornerstone of the PLE strategy [14,15,16,17]. In these environments, the tools used by the learner—repositories, applications, software—the consulted resources—journals, blogs, websites, articles—and their networks—people, contacts, digitally created and shared objects—are assessed, both quantitatively and qualitatively [8].

In the PLE context, the learner transitions from the consumer to prosumer role (this new concept is a combination of two words, producer and consumer), supported by the use of ICT, and especially Web 2.0 tools, combining non-formal and informal learning environments, both in-person and virtual [10,13,18,19,20]. Prensky [21] spoke of ‘Digital Natives and Immigrants’, whether born in a digital environment or not; in university contexts, we encounter students who do not possess an intrinsic digital domain, often referred to as ‘false digital natives’ [22], and who frequently adopt the role of ‘Visitors’ to the network rather than ‘Residents’ within that continuum [23].

In the PLE scenario, the teacher’s role shifts towards that of a coach or facilitator, becoming a ‘Network Sherpa’ [24]. This scenario still sees confusion between the use and the educational use of ICT [25]. The literature closely links PLEs to educational innovation [26], and terms such as cooperative learning, distance education, e-learning, expansive learning, video technology, video, virtual reality, Web 2.0, the embedded classroom, flipped classroom, and self-regulated learning, highlighting words like motivation, self-regulation, self-reports, self-affirmation, self-efficacy, and perceived competence. It also relates to teacher professional development with terms such as learning about teaching, knowledge for teaching, teachers’ conceptions, and teachers’ perceptions.

To face the new digital era, both personally and professionally, and to address the new generations of students, teachers need competencies related to ICT, its organizational and social dimensions, the semantic web, augmented reality, and PLEs [7,23,27,28,29,30,31].

In the educational and university context, experiences with a PLE approach are still very scarce. Among them, we highlight:

- The DIPRO 2.0 Project [19], which aims to build a PLE platform that would serve as a technological-didactic and curricular tool to train university teachers and students in educational technologies.

- The CAPPLE Project [32,33], whose objective is to conduct an exploratory study and an ad hoc questionnaire to determine the strategies and technological tools that final year university students use in their learning and communication processes.

- The teaching innovation project, in order to improve the acquisition of the competence in ICT and learning of technical contents, in a degree in engineering in industrial electronics and a master’s in industrial engineering [34]. The sequence they follow is to teach concepts related to PLEs and content curation (CC); work on resources and tools for research; definition of the students’ PLE and their needs, objectives, and achievements; and analyze the results.

- Transmedia Educational Projects or Objects (OET) involving researchers, OET coordinators, specialized teachers, technical staff providing technical support, tools and resources, experts in transmedia methodology, and, of course, the students themselves [35].

- Berbel [36] has documented an increase in academic performance, measured in terms of course grades, by integrating the PLE approach into a statistics course. This study compares the assessments of seven cohorts or groups of students, distributed among three groups without the application of PLEs and four groups with their adoption.

- Qualitative research involving 20 teachers to understand which teaching tasks affect student agency—resources used in their learning to connect, interact, and participate [1]. The impact on their PLEs primarily occurs in contextual opportunities—tools to work with, collaborate, choose what and with whom to work with—and much less on relational or personal resources.

This article focuses on educational research in the university context, applied to the subject within the master’s program in teacher training for secondary education, baccalaureates, vocational training, and languages. The goal was to work on the concept of PLEs with future teachers, introduce it to them, and have them work with it. This has allowed for a deeper understanding of the use of PLEs in the university, given the limited experiences in this field. In this context, within a group of university students, a research project was proposed to see and measure the effect of using PLE on their student agendas for a subject aimed at enhancing their digital competencies applied to the educational field. The central question was whether, after the course, their competencies related to PLE would have increased, as well as their student agendas. The following section, ‘Materials and Methods’, will provide detailed information on the research carried out. This will be followed by the main results, an analysis of these results, and conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

The experience analyzed in this article is part of research within the field of personal learning environments (PLEs) and their potential as a tool for students to enhance digital competencies and achieve greater performance and utilization of the learning process. This study focused on the subject ‘Educational Innovation and ICTs Applied to Physical Education Teaching’ during the 2022/2023 academic year. This subject is part of the master’s program in teacher training for secondary education, baccalaureates, vocational training, and languages, specializing in physical education, at Rey Juan Carlos University. It involved a total of 36 students.

2.1. Analysis of the Subject

The subject in which this work has been proposed has a duration of one semester with a session rate of 2 h per week, and its main objective is to introduce students to what educational innovation is, the principles that govern it, and to review the use of educational technology. It aims to provide students with sufficient digital competencies to carry out their future teaching tasks and to apply this technology critically, securely, and always within an effective instructional design framework.

The subject has a highly practical component, organized into sessions in computer classrooms. These sessions begin with a brief theoretical introduction, followed by the application of the knowledge presented through exercises for each session. These exercises contribute to the creation of a digital portfolio or e-portfolio and include activities to be carried out both individually and in groups outside the classroom. The purpose of both exercises and activities is to encourage students to research and delve into innovative experiences and new digital tools, which they must learn to use and apply correctly. In this way, they will develop the competencies and knowledge required by the subject from a critical perspective.

2.2. Proposal for the Implementation of PLE

One of the foundations on which the subject is based is the learning and awareness of personal learning environments. In the first topic, students are introduced to this concept and encouraged to continually enhance their PLE throughout the course using the new tools provided and the knowledge they acquire through the proposed activities.

The initial exercise presented to students, following a brief theoretical introduction by the instructor in the classroom, involves creating a diagram of their PLE at the start of the course using a digital mind mapping tool. They are required to indicate the tools, technologies, or web platforms they are familiar with and use in their daily lives.

Upon completion of the subject, one of the individual activities involves a final analysis of the evolution of the student’s PLE. They create another diagram of their PLE and compare it with their initial one. In addition, they respond to reflection questions presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reflection questions on student PLE.

Each student, in addition to submitting their practice, had to evaluate two other students and perform a self-assessment of their own submission. To manage the assessments, the ‘Workshop’ tool of the university’s Moodle platform was used, and a rubric was provided that served as a guide for the evaluation, both for the students and the teacher.

2.3. Research Design

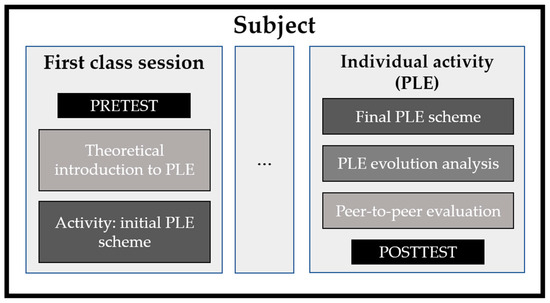

The research methodology employed has been mixed, and the outline can be seen in Figure 1. On the one hand, a longitudinal or correlational tracking study was conducted with a cohort of students, examining the course’s impact on digital competencies and the PLE (personal learning environment). This was achieved by comparing the scores on a ‘PLE test’ form (Appendix A) that students were asked to complete at the beginning (pretest) and end of the course (posttest).

Figure 1.

Research scheme. Source: own elaboration.

On the other hand, evaluations and reflections made by the students themselves regarding the course’s effect on the development of their initial PLE diagrams and those at the end of the course were analyzed (Table 1). This analysis has been qualitative, using the method of content analysis [37], which consists of identifying, coding, and categorizing the themes or patterns that emerge from the textual data. For its realization, a professor external to the subject analyzed the information provided.

As for the information and security of the students, this work has been reported to the university’s ethics committee and it was determined that no ethical principle was violated. The students knew the information on the research from the beginning. As for the tests (pre- and post-) they were anonymous, voluntary, and their completion was not related to the grade of the subject. Microsoft Forms was used as an institutional tool to collect the responses and, to relate both tests, a code was generated from information such as the initial of the name of their best friend, of their pet, etc.

The study and analysis of the students’ PLE diagrams was carried out once the subject was finished and the students were evaluated.

The ‘PLE test’ form consists of a total of 31 Likert-type questions with 5 levels [38,39,40], organized into four thematic blocks or axes: digital identity, digital competence, organization, and PLE.

It is worth noting that this study was conducted within a single institution, for a single subject, and under the guidance of a single instructor. This approach helps mitigate bias or variability associated with different institutions or instructors.

3. Results

The ‘PLE test’, consisting of 31 items, demonstrates a high level of internal reliability (alpha = 0.86). The scale was constructed by drawing from various sources or references, as indicated in the footnote of Appendix A table, serving as evidence of construct validity. During the scale’s development, input was sought from various experts in pedagogy, PLE, and ICT.

The PLE test is broken down into four components—the principal component analysis (PCA) yields a solution with four factors that account for 46% of the variability. These factors align with the anticipated theoretical model:

- TIME_ORG: Organization, time management, and tools that aid in task-time planning and control (from OT3 to OT5—Appendix A);

- CREATE_EDIT: To know, possess digital competencies related to the creation, editing, and use of internet tools; especially, content creation (from DC21 to PLE5—Appendix A);

- SEARCH_INV: To search, investigate, compare, and employ tools typical of a content curator (from PLE9 to PLE26—Appendix A);

- COLLAB_NET: Collaborate–share–disseminate, create networks (from PLE16 to ID2—Appendix A).

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

In this analysis, Table 2 shows a comparison of scores on the ‘PLE test’ at the beginning and end of the course, associated with the four factors of the theoretical model. These factors are numbered as 1 for the pretest and 2 for the posttest.

Table 2.

Student PLE reflection questions.

Which competencies and behaviors related to the construction of a PLE show the greatest increase after the course is checked. Observing the means, it is evident that the factor with the highest score is CREATE_EDIT, both at the beginning and at the end (means of 3.7 and 4.3, respectively). SEARCH_INV is the third-highest scoring factor at the beginning of the course, and second highest at the end, indicating that these online research actions are the ones that increase the most and are incorporated into the students’ PLE.

Table 3 presents the comparisons between the means (those at the beginning of the course end in 1, and those at the end in 2) for the four factors. The test conducted is the Wilcoxon t-test, a non-parametric test since the scales do not follow a normal distribution. The increase is significant in all four factors, with the most noticeable changes occurring in the SEARCH_INV and CREATE_EDIT factors (p < 0.0001). This indicates that actions related to SEARCH_INV resources on the internet are the ones that see the greatest increase and adoption in PLEs, just like those related to CREATE_EDIT content. The other factors also increase significantly, though to a slightly lesser extent.

Table 3.

Comparison between factor scores (end–beginning of course).

The Negative Ranks, in the superscripts a, d, g, j, indicate the number of cases where the means were higher at the beginning of the course (indicated with _1), in the factors Time and space management, Creation-editing, Search and Network-Collaboration. The Positive Ranks, in the superscripts b, e, h, k, indicate the number of cases where the means were higher at the end of the course (indicated with _2). The Ties, in the superscripts c, f, i and l, indicate the number of cases where the means were equal in both moments (means_2 = means_1).

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

In relation to the reflection questions about the evolution of their PLEs (Table 1) after completing the subject, a qualitative analysis of the students’ responses has been performed.

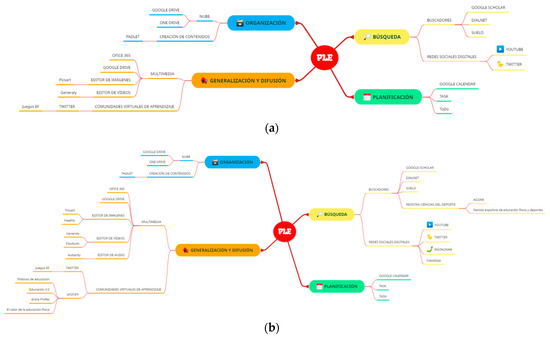

The first of the questions posed to them, regarding the technologies they added after the subject, highlighted Symbaloo, ClassDojo, or Google Classroom associated with organization; tools like Genially, Audacity, Canva, Mindomo, Kahoot, Edpuzzle, or Symbaloo for creation and editing; in research and investigation, they use Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus, or PubMed, and even social networks like TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, or Telegram; and finally, in collaboration and networking, they emphasize TikTok again, Strava (specific to sports), or Blogger. Although many tools were already being used in their previous analysis at the beginning of the course, they began to adopt new tools (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Example of a student’s personal learning environment before (a) and after (b) the course.

Regarding the second question, ‘Has knowledge of the PLE concept provided you with anything’? The students highlight how knowledge of the PLE concept has allowed them to improve the management of their information and knowledge, for example, by organizing their sources of information and digital resources more effectively. They emphasize how knowledge of the PLE concept has made them more aware of their own learning, better understanding their strengths and weaknesses, and how they can improve their learning process.

Responding to the question, ‘Do you think it is useful to analyze a PLE and its evolution’? The students emphasize the benefits of PLE analysis, such as being able to identify strengths and weaknesses in their learning process, detect opportunities for improvement, and make informed decisions. In this case, they highlight the importance of analyzing the evolution of their PLE, as it allows them to better understand their learning process, comprehend how their needs have changed, and make informed decisions on how to enhance their PLE.

When answering the question, ‘Do you think you could analyze what you have learned in a training through your PLE’? They emphasize the possibility of using their PLE to analyze what they have learned in training, allowing them to reflect on their learning process and identify areas where they need improvement. They also mention the importance of using digital tools to record and organize the information learned, which facilitates the subsequent analysis of acquired knowledge. They mention that analyzing what they have learned through the PLE allows them to consolidate and deepen their acquired knowledge, helping them retain it in the long term. They also highlight the importance of using this information to identify areas of interest and explore new topics related to what they have learned.

Finally, related to the conclusion question, they indicate that the analysis of their personal learning environment allowed them to identify the tools and digital resources that were most effective for their learning. This enabled them to optimize their study time and improve their academic performance. The students highlight tools such as educational videos, online readings, discussion forums, and online learning platforms. Another aspect was reflecting on their ability to manage their own learning, set goals, plan their activities, etc.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Knowledge and analysis of personal learning environments (PLEs) enabled students to guide and regulate their learning, from formal to informal settings. Any individual learning on the internet possesses a PLE, which can be enhanced with new tools and strategies. This research aimed to introduce the concept of PLEs to master’s students and work on it throughout the course, promoting the use of new tools and strategies. This article examines the effects of the experience conducted during the course.

The results of this study indicate that presenting a PLE approach in a course contributes to the improvement and implementation of the students’ own PLE, significantly impacting their learning. Introducing and emphasizing PLE usage in a classroom from the outset requires a coach or ‘Network Sherpa’ [24], and the facilitator must possess adequate digital competencies [23,27,28,29,30,31,41].

Following qualitative analysis, it is evident that competencies and behaviors associated with PLEs significantly improve in all dimensions: researching and investigating online, creating and editing content, collaborating and networking, and organization and time management. For most students, the process of analyzing and working on their PLE has had a profound impact. They report improved information and knowledge management, greater self-awareness of their learning, improved self-diagnosis, better control of their learning pace, enhanced ability to identify opportunities for improvement and needs, increased perceived effectiveness in information retrieval, and improved organizational skills, employing better work–learning strategies.

In line with various task proposals for PLE analysis, as outlined in Castañeda et al. [1], this experience has proposed tasks for analyzing one’s PLE and tasks to aid its evolution towards more rational use, focusing on the tools students need and strategies, as indicated in responses to questions about the evolution of their PLE.

This work, unlike others concentrating solely on tools, emphasizes the self-analysis of the PLE, in line with previous works [42] and other authors [1] who aimed to work on the student agenda.

A key element of the experience is that, although a shared PLE is developed and evaluated by other students, its creation has always been an autonomous effort centered on the individual student. One of the primary pieces of evidence for the PLE is the e-portfolio of students, which aligns with other work in higher education, including combinations with methodologies like problem-based learning.

PLEs can be related to the TPACK (technological pedagogical content knowledge) framework [43], which is a theory that aims to explain the knowledge that a teacher needs to teach their students effectively using technology. The knowledge of PLEs by teachers can help them to become aware and in control of the technologies used in the classroom, helping them to apply the principles of TPACK [44,45].

The proposed course design, although initially intended for a higher education master’s program for teacher training, could be replicated in other fields and even at earlier levels, such as undergraduate or pre-university studies.

The authors believe it is essential to analyze how learning occurs through the Internet and technology to improve the focus of tools and strategies used in PLE throughout one’s life.

The main limitation highlighted is the number of students in the research, and the next step in this investigation is to replicate this model in other contexts, including the workplace, to help professionals become aware of their PLE and actively manage it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B.G. and O.B.-G.; methodology, O.B.-G.; validation, G.B.G. and O.B.-G.; formal analysis, G.B.G.; investigation, G.B.G. and O.B.-G.; resources, O.B.-G.; data curation, G.B.G. and O.B.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.B.G.; writing—review and editing, G.B.G. and O.B.-G.; supervision, O.B.-G.; project administration, O.B.-G.; funding acquisition, O.B.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “Knowledge Generation Projects” from Spanish Research Agency grant number PID2022-137849OB-I00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Research Ethics Committee of the Rey Juan Carlos University confirms that this project (registration number: 0210202333323 and approved on 3 October 2023) does not require a certificate from the URJC Research Ethics Committee given the nature of such research, as no ethical conflict is appreciated.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

This section contains the list of questions related to the ‘PLE test’ form, differentiating the four factors of the theoretical model by means of gray and white cells.

Table A1.

PLE test questions.

Table A1.

PLE test questions.

| Questions | Rank |

|---|---|

| OT3. I spend time daily or weekly reviewing, thinking about my activities and scheduling-noting them down-following them. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| OT8. Methodologies or task managers (ToDo, Google Tasks, etc.) to manage my work and time. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| OT7. Digital notepads, online walls or some other digital tool to write down tasks and get organized | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| OT1. In my day-to-day life I organize my time using calendars, agendas, boards, etc. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| OT4. What I have to do I prepare the day before (space or place, materials I will need…). | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| OT2. In my tasks I discriminate or write down what is important, urgent and important and urgent. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| OT6. Project management platforms (Trello, Todoist, etc.) or task management platforms (ToDo, etc.) to organize my activities. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| OT5. My desk is a tidy place, I can always find everything. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| DC21. I know how to invite others and give permissions to collaborate on a shared document in the cloud. | (1) Strongly disagree/…/(5) Totally agree |

| DC2. I know how to create and edit digital text files—such as Word, OpenDocument, Google Docs | (1) Strongly disagree/…/(5) Totally agree |

| DC1. I know how to copy and move files (documents, images, videos) between folders, on my devices or in the cloud. | (1) Strongly disagree/…/(5) Totally agree |

| DC3. I am aware of technical solutions that make it easier for me to access digital content, such as translation into my language, screen magnification or text-to-speech functionality. | (1) Strongly disagree/…/(5) Totally agree |

| PLE23. I can create multimedia material—videos, logos, presentations, podcasts, etc.—in my learning process. | (1) Strongly disagree/…/(5) Totally agree |

| PLE2. I relate online information to my previous experience and knowledge. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE4. I am good at finding information on the Internet. | (1) Strongly disagree/…/(5) Totally agree |

| PLE13. Technology helps me to be creative in creating my own content. | (1) Strongly disagree/…/(5) Totally agree |

| PLE5. I compare information from different online sources in my learning process. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE9. I participate in online discussions, developing my argumentation and consensus building skills. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE1. I use specific tools (specialized search engines, databases, etc.) to find information. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE15. I search the Internet to complement the information received in my courses/classes. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE24. When I consult the Internet, I follow links to understand or go deeper into a topic. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE21. I use the Internet to keep up to date with national and international developments. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE3. I share information—data, news…—through the Internet. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE17. I share information online respecting distribution and copyright issues. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE26. I search for information online, do research on the Internet. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE22. I share knowledge, information and resources—with other students, learners or experts—through Virtual Learning Communities—like Moodle, Twitter, Wikipedia. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE16. I generate—create content in a collaborative way—with others—with online tools—Drive, One, Dropbox… | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE25. I use different formats to DISSEMINATE information—video, podcast, images, text, etc. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE16. Genero—I create content on the Internet—images, texts, comments, etc… | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| PLE14. I maintain online contact with professionals in my area of interest. | (1) Never/…/(5) Very often |

| id2. There are people who follow me on my social networks, whom I influence. | (1) 0/(2) 1/(3) 2–5/(4) 6–50/(5) >50 |

Note: The acronym indicates the origin of the item used in the test: PLE__[38]/id__[39]/DC__[40]/OT__[46].

References

- Castañeda, L.; Marín, V.I.; Scherer Bassani, P.; Camacho, A.; Forero, X.; Pérez, L. Academic Tasks for Fostering the PLE in Higher Education: International Insights on Learning Design and Agency. Red 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornella, A. Cómo Darse de Baja y Evitar La Infoxicación En Internet. Rev. Infonomía 1996, 187, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, M. A Pedagogy of Abundance. Rev. Española Pedagog. 2011, 69, 223–235. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez Gavira, R.; Aguilar Gavira, S. Entornos Virtuales Para Atender La Diversidad. Hachetetepé 2015, 1, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, L.; Dabbagh, N.; Torres-Kompen, R. Personal Learning Environments: Research-Based Practices, Frameworks and Challenges. N. Appr. Ed. R. 2017, 6, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- César, C.; Engel, A. Los Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje En Contextos de Educación Formal. Cult. Educ. Cult. Educ. 2014, 26, 617–630. [Google Scholar]

- Prendes, P.; García Román, M. Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje: Una Visión Actual de Cómo Aprender con Tecnologías; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2017; ISBN 978-84-9921-901-1. [Google Scholar]

- Jordi Adell Explica Qué Es El P.L.E. Personal Learning Environment. YouTube. 2017. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WHCN_5S7T7U (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Adell, J.; Castañeda, L. Los Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje (PLEs): Una Nueva Manera de Entender El Aprendizaje. In Claves Para la Investigación en Innovación y Calidad Educativas. La Integración de las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación y la Interculturalidad en las aulas. Stumenti di Ricerca per L’innovaziones e la Qualità in Ámbito Educativo; Editorial Marfil: Roma, Italy, 2010; ISBN 978-84-268-1522-4. [Google Scholar]

- Attwell, G. Personal Learning Environments—The Future of eLearning? eLearning Pap. 2007, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffert, S.; Hilzensauer, W. On the Way towards Personal Learning Environments: Seven Crucial Aspects. eLearning Pap. 2008, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen, D.H. Learning to Solve Problems with Technology: A Constructivist Perspective; Merrill: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-13-048403-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dabbagh, N.; Castaneda, L. The PLE as a Framework for Developing Agency in Lifelong Learning. Educ. Tech. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 3041–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conole, G. MOOCs as Disruptive Technologies: Strategies for Enhancing the Learner Experience and Quality of MOOCs. Rev. Educ. Distancia 2015, 39, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, F.; Mödritscher, F.; Sigurdarson, S. Designing for Change: Mash-up Personal Learning Environments. eLearning Pap. 2008, 9. Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/25253/ (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Reinders, H. Personal Learning Environments for Supporting Out-of-Class Language Learning. Engl. Teach. Forum 2014, 52, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tzavara, A.; Lavidas, K.; Komis, V.; Misirli, A.; Karalis, T.; Papadakis, S. Using Personal Learning Environments before, during and after the Pandemic: The Case of “e-Me”. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, J.; Banyard, P. Managers’, Teachers’ and Learners’ Perceptions of Personalised Learning: Evidence from Impact 2007. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2008, 17, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero, J.A. Creación de Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje Como Recurso Para La Formación. El Proyecto Dipro 2.0. Edutec-e 2014, 47, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. The Shift to Learning Outcomes: Conceptual, Political and Practical Developments in Europe; Office for Official Publication of the European Communities: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 2: Do They Really Think Differently? Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, C. Undividing the Digital? The Power of Narrative Research to Uncover the Hidden Complexities of Students’ Digital Practice. In Proceedings of the European Distance and E-Learning Network (EDEN) Conference Proceedings, Jonkoping, Sweden, 13–16 June 2017; Volume 1, pp. 280–295. [Google Scholar]

- White, D.S.; Le Cornu, A. Visitors and Residents: A New Typology for Online Engagement. First Monday 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couros, A. Visualizando La Enseñanza Abierta. In Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje: Claves para el Ecosistema Educativo en Red; Castañeda, L., Adell, J., Eds.; Editorial Marfil: Alcoy, Spain, 2013; pp. 179–183. ISBN 978-84-268-1638-2. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano Sánchez, J.L.; Gutiérrez Porlán, I.; Prendes Espinosa, M.P. Internet Como Recurso Para Enseñar y Aprender: Una Aproximación Práctica a La Tecnología Educativa; RELATEC: Cáceres, Spain, 2016; Volume 3, pp. 171–172. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda Quintero, L.J.; Tur Ferrer, G.; Torres Kompen, R. Impacto Del Concepto PLE En La Literatura Sobre Educación: La Última Década. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2019, 22, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydas, O.; Kucuk, S.; Yilmaz, R.M.; Aydemir, M.; Goktas, Y. Educational Technology Research Trends from 2002 to 2014. Scientometrics 2015, 105, 709–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero-Almenara, J. La Educación a Distancia Como Estrategia de Inclusión Social y Educativa. Rev. Mex. Bachill. Distancia 2016, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Martínez, J.A.; Bote-Lorenzo, M.L.; Gómez-Sánchez, E.; Cano-Parra, R. Cloud Computing and Education: A State-of-the-Art Survey. Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veletsianos, G.; Kimmons, R. Scholars in an Increasingly Open and Digital World: How Do Education Professors and Students Use Twitter? Internet High. Educ. 2016, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrastinski, S.; Aghaee, N.M. How Are Campus Students Using Social Media to Support Their Studies? An Explorative Interview Study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2012, 17, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendes, P.; Castañeda, L. Analysis of the Future Professionals’ PLEs as Lifelong Learning Basic Skill: Presenting the CAPPLE Project. In Proceedings of the PLE Conference, Berlin, Germany and Melbourne, Australia, 10–12 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Román García, M.D.M.; Prendes Espinosa, M.P. Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje: Instrumento Cuantitativo Para Estudiantes Universitarios (CAPPLE-2). Edutec. Rev. Electrónica Tecnol. Educ. 2020, 73, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalina Ruz, C.; Jiménez Castillo, C.; Eliche Quesada, D.; La Rubia García, M.D.; Aguilar Peña, J.D. Curación de Contenidos y Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje Como Herramienta de Aprendizaje En Ingeniería Electrónica. In Proceedings of the XIV Congreso de Tecnologías Aplicadas a la Enseñanza de la Electrónica: Proceedings TAEE, Porto, Portugal, 25–27 June 2020; pp. 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Rodrigo, L.; Majó, A.E.; Tió, E.V. Teenpods: Production of Educational Videos as First Step in a Transmedia Educational Project About Positive Youth Development. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Education 2021: Official Conference Proceedings, London, UK, 15–18 July 2021; pp. 363–370. [Google Scholar]

- Berbel Giménez, G. Efecto de Un Entorno Personal de Aprendizaje Sobre La Asignatura de Estadística En El Grado de Turismo (EUMediterrani, UdG). Co. Games Bus. Simul. Acad. J. 2022, 1, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis an Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-5063-9567-8. [Google Scholar]

- García-Martínez, J.-A.; González-Sanmamed, M.; Muñoz-Carril, P.-C. Validation of the Activities’ Scale in Higher Education Students’ Personal Learning Environments. Psicothema 2021, 33, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, L.; Camacho, M. Desvelando Nuestra Identidad Digital. Prof. Inf. 2012, 21, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- European Commission. Joint Research Centre. DigComp 2.2, The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens: With New Examples of Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes; Joint Research Centre: Brussel, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Prendes Espinosa, M.P.; Solano Fernández, I.M.; Serrano Sánchez, J.L.; González Calatayud, V.; Román García, M.D.M. Entornos Personales de Aprendizaje Para La Comprensión y Desarrollo de La Competencia Digital: Análisis de Los Estudiantes Universitarios En España. Educatio 2018, 36, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Navarro, J.; Jiménez-Rivero, A.; Borrás-Gené, O. Personal Learning Environments as the Basis of a New Course for Master’s Programmes. In Proceedings of the INTED2018 Proceedings, Valencia, Spain, 5–7 March 2018; IATED: Valencia, Spain, 2018; pp. 1313–1319. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaadaway, M.A.N.; Abouelenein, Y.A.M. In-Service Teachers’ TPACK Development through an Adaptive e-Learning Environment (ALE). Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 8273–8298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaipidech, P.; Srisawasdi, N.; Kajornmanee, T.; Chaipah, K. A Personalized Learning System-Supported Professional Training Model for Teachers’ TPACK Development. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covey, S.R. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-982137-13-7. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).