“Building Roots”—Developing Agency, Competence, and a Sense of Belonging through Education outside the Classroom

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Education Outside the Classroom

1.2. Self-Determination Theory

1.3. Ecological Psychology

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Ethnographic Case Study

2.2. Participants/the Field

2.3. Ethical Considerations

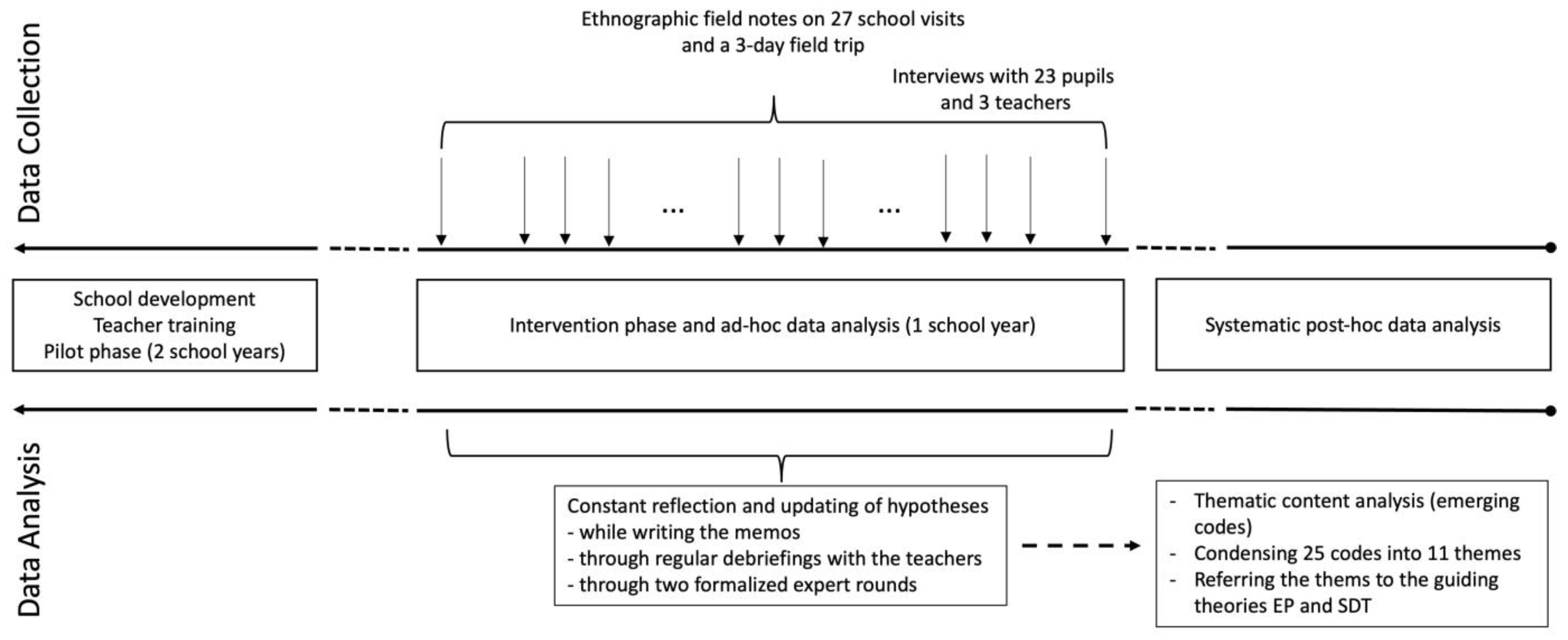

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Ethnographic Fieldwork

2.4.2. Regular Debriefings with the Teachers

2.4.3. Semi-Structured Interviews with Teachers at the End of the School Year

2.4.4. Guided Interviews with Students at the End of the School Year

2.4.5. Two Expert Rounds

3. Results

3.1. The Need for Competence: To Feel Effective

“The interest of the children alone/they were totally involved in the topic, right from the beginning when we marched in there [into an art exhibition at the local museum] in a spiral, and I told them a few facts/but also later, when we broke up into groups/and the children lay on the floor all over the museum and somehow drew something according to Hundertwasser, and you really noticed that they had totally understood what the artist wanted to express, in his entire life actually/what he wanted to say, they got that and somehow wrote it down or painted it in their notebooks” (class teacher, 2nd grade). (The symbol “/” signifies a noticeable pause in the speech flow. Ellipses “(…)” are used to express an omission. Words in brackets “[]” are added by the author to make the quote more readable.)

3.1.1. Assistance and Support

“well, sometimes the ‘strong’ students who do everything with ease in class may not shine in EOtC and erm/maybe that’s not really their thing/but that the ‘weak’ students who actually/in class/have a lot of experiences of failure, then when [they are] outside and (uhh) [are] digging for potatoes or something (…); well, they simply have a completely different task/or they are challenged in a completely different way and also have a sense of achievement”.(class teacher, 2nd grade)

“We went to ‘Nussallee’ [an alley close to the school with many chestnut trees], we estimated the [length of the] alley, we measured how long it is, and walked along Nussallee once and measured the time [this took] and measured it [again] once while jogging and once at full speed. And then we went back to school and then calculated it, the speed, as it had been in each case. And after the unit, all the kids knew what speed is. Because they experienced it themselves with their own bodies and this was then also reflected in the written tests afterwards/the [positive] results simply reflected that this really was the case, that it wasn’t just a guess on my part”.(head mistress)

3.1.2. Providing Structure

“When they [the teachers] explain something, they often show things and then we often don’t see anything because everyone is jostling and then I can’t really hear either and then I mostly talk to my girlfriends.”

3.2. The Need for Autonomy: To Feel Agentic

“I can totally identify a motivation to learn [in EOtC]/when I observe the children, when I’m outside with them (…) how committed they are, how they try to solve their assignments together in a team, how they communicate, how (…) high their agency is in comparison to the lessons [inside]”.(head mistress)

3.2.1. Providing Opportunities for Freedom, Discoveries, and Choices

“Because you learn something from nature there [outside], I think that’s nice first (...) because you sometimes see animals, such as a rabbit, hopping across the meadow, for example when you walk along/that happens sometimes and you can also get very close to the birds that are in the bushes. They don’t come fluttering into the school building and then you can also learn about the animals when you’re outside, you can’t do that so well inside”.

“When they look for objects to measure (…) there is a much greater variety outdoors and then they also have the option to look for a quiet small place to take the measurements by themselves and this makes a big difference”.(head mistress)

“They are totally excited about the variety that is out there. They quickly realized that in the village and in our school surroundings they find much more learning opportunities than in a closed room”.(head mistress)

3.2.2. Relevance to Everyday Life

“I’’s just nice, because you can sometimes also play games and when we study outside, you also learn something from nature, not just something from books and such”.(girl, 2nd grade)

“What really impressed me was how the children intuitively ran after this watercourse here on the street, where I thought, yes, that’s exactly it [what EOtC offers]”.(teacher, 3rd grade)

“The children learned so incredibly much in one morning that I would not have been able to pack this into ten school lessons in the classroom. This assignment was incredibly rich, it contained plus calculation, estimating, there was weighing, ingredients of food, transport routes, there was packaging material and where does the waste go to, i.e., the whole area of environmental issues like disposal and recycling, then there was organic vs. conventionally produced food, self-made vs. convenient food products, healthy and unhealthy nutrition habits (…) that was, really, it was so full! And the children certainly remembered that much more than/well, there are also pages in the schoolbook about it, but I believe that the effect is much greater if you do it right on the spot, in small groups”.(head mistress)

3.3. The Need for Relatedness: To Feel Connected

“When I take part in things, when I get involved in something, when I get committed, then I am also a part of it”.(head mistress)

3.3.1. Peer Connections

“I have the feeling that my evaluation of the social structures in class are more pronounced in EOtC (…) I sense that the same [social structures] that I notice in the classroom become more visible in the outdoors, not different”.(teacher, 3rd grade)

“I do believe that because of the long time period/that is, during the whole mornings/when they [the students] have to work together in their group/they develop a stronger sense of belonging together in a different way than they would do at school (…) that they are able to get to know each other’s strengths and maybe also weaknesses and accept them”.(class teacher, 2nd grade)

3.3.2. Student–Teacher Connection

“She [the teacher] just has to be a bit more careful [outside], because if someone gets lost, you have to go back and search everything, and she has to be a bit stricter because she has to make sure that we all stay together”.(girl, 2nd grade)

3.3.3. Connection to Place and Community

“The main effect is that the children can develop a strong bond with the village, that they can recognize their roots/basically it’s about the roots/and the children are the roots of the village (…) and I would like to be part of this village, or I am a part of this village and I would also like to do something in return, because the village also needs something”.(head mistress)

“I think if EOtC wasn’t also accepted by the parents, then they wouldn’t support it as much. And some of them take vacation time to be able to accompany us (…) That is also an element of EOtC, the involvement, the participation (…) of parents in school life, the opportunities to help shape it and that is what EOtC offers perfectly. Because it’s not just about baking cakes anymore”.(head mistress)

3.4. The Need for Time Spent in Nature

“Because outdoors nature is more close (…) and I like nature very much and that’s why I also want to be outdoors. So that you get to know her [nature], so that you get to love her. And not just be inside and not loving her at all”.(boy from 2nd grade)

3.4.1. Aesthetic and Restorative Properties of the Outdoors

3.4.2. Immersive Properties of the Outdoors

“That was a moment when I thought, yes, exactly, they are connecting something that is very important to them, that is very valuable to them, and connect it with a creative expression. And for me that actually is the highest form of art, to combine the emotional with the creative”.(head mistress)

“I have the impression that what the children have learned outside, that they have firmly anchored it in their consciousness, that they remember it, and, in the tests, they also show that they have understood it”.(head mistress)

4. Discussion and Implications

4.1. The Need for Competence

4.2. The Need for Autonomy

4.3. The Need for Relatedness

4.4. The Need for Time Spent in Nature

4.5. Strenghts and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| School-Visit | Class | Month | Primary site | Primary Learning Goal | Secondary Sites | Secondary Learning Moments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | September | Classroom | First-aid workshop, part I (Red Cross junior helper) | School yard | --- |

| 2 | 3 | September | Classroom | First-aid workshop, part II (Red Cross junior helper) | School yard, close surroundings of school | ---- |

| 3 | 2 | October | Market stall at the local food market on the square in front of the train station | Differences between fruit and vegetable; seasonal/native fruit and vegetable; where do the products come from? | Community garden; (about 2 km) walk through the park landscape | Identifying several fruit species; purchasing and paying (calculating) |

| 4 | 3 | October | Wood and park landscape around the school | The Forest, part I (experiential educational games) | Walk to the sites and back (about 1 km) | Games to enhance class cohesion |

| 5 | 2 | October | Classroom (actually an outdoor session about the common earthworm was planned, but it needed to be cancelled because of time pressure due to the upcoming test) | Revision of lessons about fruit/vegetable (preparation for upcoming test); healthy nutrition; calculating within the number range over 100 | Public library located in the nearby monastery; walk to the library and back through the park (about 1 km) | How to loan books; how to find stuff in a library; how to behave in a library |

| 6 | 3 | November | Different sites of conifers in the park landscape around the school | The Forest, part II; conifers | Walk to the sites and back (about 1.5 km) | Activity plays; class cohesion |

| 7 | 2 | November | Area in the woods in the surroundings of the school with lots of dead wood | Building and constructing a shelter | Walk to the site and back; a sunny meadow behind the construction area | Activity plays |

| 8 | 3 | December | Local fire brigade | Learning about the fire brigade | Walk to the site and back (about 400 m) | ---- |

| 9 | 2 | December | The local Art Museum: visit of the Hundertwasser-exhibition | Learning about the artist Hundertwasser; preparing own drawings inspired by the artist | About 3 km hike to and from the museum through park landscape and along a lake | Lifecycles in nature (inspecting a decaying tree trunk at the side of the path); connections to Hundertwasser’s recurring motive of the “spiral” to symbolize life-cycles |

| 10 | 3 | January | Snow-covered meadow with a slope close to the school | Experiments around fire with the aim to come up with own hypotheses and to test them: how to build a campfire; how do different materials burn (cotton wool, fabric, wool, tinfoil, stone, etc.) | Wider area around the slope; Walk to the site and back (about 400 m); Slope itself | Sledding |

| 11 | 2 | January | Snow-covered meadow with a slope close to the school | Sledding (as part of PE) | Wider area around the slope; Walk to the site and back (about 400 m) | Playing in the snow; building a snow-sofa |

| 12 | 1-4 | January | Rehearsal room of the local brass band in the former ‘old’ school building | Differences between wood- and brass instruments; how to play a brass instrument | Walk through the village to the old school building and back (about 800 m) | Getting to know about the local brass band; history of the school |

| 13 | 1-4 | January | Gasteig, a big concert house in Munich | Visit of a concert for children | Public transport to and in Munich (about 40 km) | Orienteering on a map; using public transport |

| 14 | 2 | February | Farmstead of the mayor in the village center | Learning about farm and domestic animals (what do they eat, what do they need); learning about the profession of a farmer | Walk through the village to the mayor1s farm (about 1.5 km); School yard; Classroom (visit from a student’s grandfather with his dog): What does a dog need/eat, etc. | Changes in farming from previous times until today; how to prepare a presentation about one’s favorite pet |

| 15 | 3+1 | March | The local Art Museum: visit of the Hundertwasser-exhibition (with two other classes) | Learning about the artist Hundertwasser; preparing own drawings inspired by the artist | About 3 km hike to and from the museum through park landscape and along a lake | Getting to know about the local businesses along the way (e.g., the hotel); older students needed to take care of younger ones |

| 16 | 2 | March | Different meadows in the park landscape around the school | Classifying wildflowers | Walks through the park to the sites and back (about 1 km) | Collecting flowers in order to press them for an herbarium |

| 17 | 2 | March | Meadow, walking path and a dirt mound in the park landscape close to the school | Experiments around ‘air ‘to find out more about its properties | Walk to the site and back (about 500 m) | Activity games |

| 18 | 3 | March | Classroom | Experiments around electricity; specifically kinetic energy | Gym (testing out spools the students had built) | How to conduct scientific experiments |

| 19 | 3 | April | Classroom | Learning about vision/how we see/parts of the human eye | --- | How to conduct scientific experiments |

| 20 | 3 | May | Park landscape and woods surrounding the school | Visit of the local forester: what is so special about this specific forest; What does a forester do | Walks through the park landscape (about 2 km) | Discovering a fox burrow and therefore learning about foxes; experiential educational games |

| 21 | 1-4 | May | Local monastery | Learning about the history of the village and the role of the monastery | Walk through the park and village to the site and back (about 1 km) | Different possibilities to preserve history (e.g., through a wall painting) |

| 22 | 1-4 | May | The school’s assembly hall | Presenting a poster with the model for the planned ball path by the students of the second grade; explaining what will happen on the project day | School yard | How to do a presentation in front of many people |

| 23 | 2 | May | School yard | Experimenting with building a prototype for the ball path | Meadow and slope behind the school building | How to measure; how to saw |

| 24 | 1-4 | May | School yard; grounds around the school | Whole school project day: construction of the common ball path; working in smaller groups to build single parts for the common ball path | meadow and slope behind the school: this is where at the end of the day, the separate parts will be constructed into one big ball path | Working together in mixed-aged groups; working together with experts; conducting interviews for a local radio feature |

| 25 | 3 | June | Park landscape around the school | Learning about native ‘wild’ animals through a visiting expert | Walks around the park to different sites (about 2 km) | --- |

| 26 | 2 | July | Several businesses and companies all over the village (bakery, boat building yard, monastery, hotel, fishery, pharma company, carpenter’s workshop, dentist, physiotherapist, collection station, childcare center) | Learning about the local businesses and companies; getting to know different professions | Walks around the village (about 3 km) | How to do interviews; how to record interviews; how to create a portfolio about different professions (this would be done later in the classroom with the information gathered that day) |

| 27 | 3 | July | Visit of the local archive | Learning about the history of the village | Walk through the village to the site and back (about 1.5 km) | How to keep history alive; what to learn from archives |

| 28 | 3 | June | 3-day Residential Berchtesgaden | The water-cycle; how water formed the landscape | National Park; National Park Visitor Centre (with workshop) | Who lives in the stream? Determining water quality by examining animals in the water |

References

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mygind, E. Udeskole—TEACHOUT-Projektets Resultater; Frydenlund: Frederiksberg, Denamark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jucker, R.; von Au, J.A. High-Quality Outdoor Learning—Evidence-Based Education Outside the Classroom for Children, Teachers and Society; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Remmen, K.B.; Iversen, E. A scoping review of research on school-based outdoor education in the Nordic countries. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2022, 23, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsen, P.; Mygind, E.; Randrup, T. Towards an understanding of udeskole: Education outside the classroom in a Danish context. Education 3-13 2009, 37, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braund, M.; Reiss, M. Towards a more authentic science curriculum: The contribution of out-of-school learning. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2006, 28, 1373–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quay, J. Experience and Participation: Relating Theories of Learning. J. Exp. Educ. 2003, 26, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beames, S.; Higgins, P.J.; Nicol, R. Learning Outside the Classroom: Theory and Guidelines for Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; Volume xiii, 126p. [Google Scholar]

- Waite, S.J. Children Learning Outside the Classroom: From Birth to Eleven; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mygind, E. A comparison between children’s physical activity levels at school and learning in an outdoor environment. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2007, 2, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, E. Physical Activity during Learning Inside and Outside the Classroom. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2016, 3, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneller, M.B.; Bentsen, P.; Nielsen, G.; Brond, J.C.; Ried-Larsen, M.; Mygind, E.; Schipperijn, J. Measuring Children’s Physical Activity: Compliance Using Skin-Taped Accelerometers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bølling, M.; Mygind, E.; Mygind, L.; Bentsen, P.; Elsborg, P. The Association between Education Outside the Classroom and Physical Activity: Differences Attributable to the Type of Space? Children 2021, 8, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettweiler, U.; Becker, C.; Auestad, B.H.; Simon, P.; Kirsch, P. Stress in School Some Empirical Hints on the Circadian Cortisol Rhythm of Children in Outdoor and Indoor Classes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.; Schmidt, S.; Neuberger, E.; Kirsch, P.; Simon, P.; Dettweiler, U. Children’s Cortisol and Cell-Free DNA Trajectories in Relation to Sedentary Behavior and Physical Activity in School: A Pilot Study. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, L.; Kjeldsted, E.; Hartmeyer, R.; Mygind, E.; Bolling, M.; Bentsen, P. Mental, physical and social health benefits of immersive nature-experience for children and adolescents: A systematic review and quality assessment of the evidence. Health Place 2019, 58, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Human Behavior and the Environment; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature; Cambridge Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bølling, M.; Pfister, G.U.; Mygind, E.; Nielsen, G. Education outside the classroom and pupils’ social relations? A one-year quasi-experiment. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 94, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmeyer, R.; Mygind, E. A retrospective study of social relations in a Danish primary school class taught in ‘udeskole’. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2015, 16, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bølling, M.; Niclasen, J.; Bentsen, P.; Nielsen, G. Association of Education Outside the Classroom and Pupils’ Psychosocial Well-Being: Results From a School Year Implementation. J. Sch. Health 2019, 89, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauterbach, G.; Fandrem, H.; Dettweiler, U. Does “Out” Get You “In”? Education Outside the Classroom as a Means of Inclusion for Students with Immigrant Backgrounds. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 878. [Google Scholar]

- Mygind, E.; Bølling, M.; Barfod, K.S. Primary teachers’ experiences with weekly education outside the classroom during a year. Education 3-13 2019, 47, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bølling, M.; Otte, C.R.; Elsborg, P.; Nielsen, G.; Bentsen, P. The association between education outside the classroom and students’ school motivation: Results from a one-school-year quasi-experiment. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 89, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettweiler, U.; Ünlü, A.; Lauterbach, G.; Becker, C.; Gschrey, B. Investigating the motivational behaviour of pupils during outdoor science teaching within self-determination theory. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczytko, R.; Carrier, S.J.; Stevenson, K.T. Impacts of Outdoor Environmental Education on Teacher Reports of Attention, Behavior, and Learning Outcomes for Students with Emotional, Cognitive, and Behavioral Disabilities. Front. Educ. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrable, A.; Arvanitis, A. Flourishing in the forest: Looking at Forest School through a self-determination theory lens. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2018, 22, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Vansteenkiste, M. Self-determination theory and basic need satisfaction: Understanding human development in positive psychology. Ric. Di Psichol. 2004, 27, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.W. Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychol. Rev. 1959, 66, 297–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govorova, E.; Benitez, I.; Muniz, J. Predicting Student Well-Being: Network Analysis Based on PISA 2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G.; Flowerday, T.; Lehman, S. Increasing Situational Interest in the Classroom. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 13, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Darst, P.W.; Pangrazi, R.P. An examination of situational interest and its sources. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 71, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Sierens, E.; Soenens, B.; Luyckx, K.; Lens, W. Motivational Profiles from a Self-Determination Perspective: The Quality of Motivation Matters. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierens, E.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Goossens, L.; Soenens, B.; Dochy, F. The synergistic relationship of perceived autonomy support and structure in the prediction of self-regulated learning. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 79, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, M.P.; DeVille, N.V.; Elliott, E.G.; Schiff, J.E.; Wilt, G.E.; Hart, J.E.; James, P. Associations between Nature Exposure and Health: A Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D.E.; Pelletier, L.G. Is nature relatedness a basic human psychological need? A critical examination of the extant literature. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 2019, 60, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrable, A.; Booth, D.; Adams, D.; Beauchamp, G. Enhancing Nature Connection and Positive Affect in Children through Mindful Engagement with Natural Environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Commodities and Capabilities; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999; 89p. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, L. Passive patient or active agent? An under-explored perspective on the benefits of time in nature for learning and wellbeing. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 942744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeHaan, C.R.; Hirai, T.; Ryan, R.M. Nussbaum’s Capabilities and Self-Determination Theory’s Basic Psychological Needs: Relating Some Fundamentals of Human Wellness. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 17, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Chemero, A. An Outline of a Theory of Affordances. Ecol. Psychol. 2003, 15, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withagen, R. The Field of Invitations. Ecol. Psychol. 2023, 35, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerstrup, I.; Chawla, L.; Heft, H. Affordances of Small Animals for Young Children: A Path to Environmental Values of Care. Int. J. Early Child. Environ. Educ. 2021, 9, 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pyysiäinen, J. Sociocultural affordances and enactment of agency: A transactional view. Theory Psychol. 2021, 31, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heft, H. Perceiving “Natural” Environments: An Ecological Perspective with Reflections on the Chapters. In Nature in Psychology—Biological, Cognitive, Developmental, and Social Pathways to Well-Being; Schutte, A.R., Torquati, J.C., Stevens, J.R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Basel, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 235–273. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, L. Knowing nature in childhood: Learning and well-being through engagement with the natural world. In Nature and Psychology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 153–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, E. Principles of Perceptual Learning and Development; Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Heft, H. Affordances and the perception of landscape: An inquiry into environmental perception and aesthetic. In Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health; Thompso, C.W., Aspinall, P., Bel, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sääkslahti, A.; Niemistö, D. Outdoor activities and motor development in 2–7-year-old boys and girls. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2021, 21, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L.; Heft, H. Children’s Competence and the Ecology of Communities: A Functional Approach to the Evaluation of Participation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L.; Derr, V. The development of conservation behaviors in childhood and youth. In The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology; Clayton, S.D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 527–555. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, D. Place-Based Education: Connecting Classrooms and Communities, 2nd ed.; Orion: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 2013; p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, C.; Lauterbach, G.; Spengler, S.; Dettweiler, U.; Mess, F. Effects of Regular Classes in Outdoor Education Settings: A Systematic Review on Students’ Learning, Social and Health Dimensions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.; Gray, T.; Truong, S.; Brymer, E.; Passy, R.; Ho, S.; Sahlberg, P.; Ward, K.; Bentsen, P.; Curry, C.; et al. Getting Out of the Classroom and Into Nature: A Systematic Review of Nature-Specific Outdoor Learning on School Children’s Learning and Development. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 877058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagin, J.R.; Orum, A.M.; Sjoberg, G. A Case for the Case Study; CAB International: Wallingford, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, R. Being Ethnographic: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Ethnography; SAGE: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Breidenstein, G.; Hirschauer, S.; Kalthoff, H.; Nieswand, B. Ethnografie. Die Praxis der Feldforschung; UVK Verglagsgesellschaft mbH: Konstanz/München, Germany, 2015; Volume 3979. [Google Scholar]

- Metz, M.H. What can be learned from educational ethnography? Urban Educ. 1983, 17, 391–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotter, R.T., 2nd. Qualitative research sample design and sample size: Resolving and unresolved issues and inferential imperatives. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 398–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.E. “I Am a Fieldnote”: Fieldnotes as a symbol of professional identity. In Fieldnotes: The Makings of Anthropology; Sanjek, R., Ed.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA; London, UK, 1990; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwaa, L. Creating Protocols for Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research. J. Cult. Divers. 2016, 23, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seidman, I.E. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences, 4th ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, S.; Hogan, D. Researching Children’s Experience: Methods and Approaches; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kutrovátz, K. Conducting qualitative interviews with children: Methodological and ethical challenges. Corvinus J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2017, 8, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtman, M. Qualitative Research for the Social Sciences; SAGE Publications: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, D.; Bagley, C.; Marques da Silva, S. The Wiley Handbook of Ethnography of Education, 1st ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tummons, J.; Beach, D. Ethnography, materiality, and the principle of symmetry: Problematising anthropocentrism and interactionism in the ethnography of education. Ethnogr. Educ. 2019, 15, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenewald, D.A. Foundations of Place: A Multidisciplinary Framework for Place-Conscious Education. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 40, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, C.; Au, J.v.; Dettweiler, U. Students’ appropriation of space in education outside the classroom. some aspects on physical activity and health from a pilot study with 5th-graders in Germany. In Nature and Health. Physical Activity in Nature; Brymer, E., Rogerson, M., Barton, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Fiskum, T.A.; Jacobsen, K. Outdoor education gives fewer demands for action regulation and an increased variability of affordances. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2013, 13, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbrüster, C.; Gräfe, R.; Harring, M.; Sahrakhiz, S.; Schenk, D.; Witte, M.D. Inside We Learn, outside We Explore the World—Children’s Perception of a Weekly Outdoor Day in German Primary Schools. J. Educ. Hum. Dev. 2016, 5, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneller, M.B.; Duncan, S.; Schipperijn, J.; Nielsen, G.; Mygind, E.; Bentsen, P. Are children participating in a quasi-experimental education outside the classroom intervention more physically active? BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.J.; Zimmerman, H.T.; Land, S.M. Emerging and developing situational interest during children’s tablet-mediated biology learning activities at a nature center. Sci. Educ. 2019, 103, 900–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettweiler, U.; Lauterbach, G.; Mall, C.; Kermish-Allen, R. Fostering 21st century skills through autonomy supportive science education outside the classroom. In High-Quality Outdoor Learning: Evidence-Based Education Outside the Classroom for Children, Teachers and Society; Jucker, R., von Au, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 231–253. [Google Scholar]

- Skalstad, I.; Munkebye, E. How to support young children’s interest development during exploratory natural science activities in outdoor environments. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 114, 103687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettweiler, U.; Gerchen, M.; Mall, C.; Simon, P.; Kirsch, P. Choice matters: Pupils’ stress regulation, brain development and brain function in an outdoor education project. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 93 (Suppl. S1), 152–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glackin, M. ‘Control must be maintained’: Exploring teachers’ pedagogical practice outside the classroom. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2018, 39, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinger, J.; Mess, F.; Bachner, J.; von Au, J.; Mall, C. Changes in social interaction, social relatedness, and friendships in Education Outside the Classroom: A social network analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1031693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikaels, J. Becoming a Place-Responsive Practitioner: Exploration of an Alternative Conception of Friluftsliv in the Swedish Physical. J. Outdoor Recreat. Educ. Leadersh. 2018, 10, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, J.; Köster, M.; Lange, F.; Fischer, M.; Moors, A. A Goal-Discrepancy Account of Restorative Nature Experiences. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stereotypical Situation | Codes | EP-Related Themes | Basic Psychological Need | Difficulties and Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assisting student learning and well-being through hands-on activities that enable them to show different sides of themselves. | role of the teacher showing different sides of oneself hands-on activities physical activity bodily/sensory experiences structure and rituals | qualities of the outdoors affordances of the outdoors embodied experiences | Competence | unsuitable group constellations teachers’ insecurities, unfamiliarity with places and people, and lack of interest |

| Assisting student learning and well-being through providing safety and structure (rules, rituals, precise instructions). | difficult to maintain control of and communication with class over a larger area rituals need practice (time consuming) students are more easily distracted outside | |||

| Assisting student-learning and well-being through providing opportunities for freedom, discoveries, and choices. | physical activity freedom curiosity relation to everyday life role of the teacher flow joy | Autonomy | finding the right balance between freedom and control great responsibility for student safety less control over learning outcomes due to the rich and sometimes unpredictable qualities of the outdoors | |

| Assisting student-learning and well-being through relevance to everyday life. | ||||

| Assisting students’ well-being through fostering peer connections. | social aspects physical activity freedom fresh air hands-on activities role of the teacher place and people sharing experiences with the family showing different sides of oneself friends students’ reflections on teachers | Relatedness | social structures from inside are reinforced outside without teacher-intervention building new peer connections takes time | |

| Assisting students’ well-being through strengthening student–teacher connection. | ||||

| Assisting students’ well-being through establishing connections to place and community. | teachers’ insecurities, unfamiliarity with places and people, and lack of interest | |||

| Assisting students’ well-being through aesthetic and restorative qualities of the outdoors. | physical activity freedom fresh air noise aesthetic experiences curiosity bodily/sensory experiences hands-on activities role of the teacher place and people flow joy lasting memories | Nature | finding the “right” place disturbances need to be addressed immediately | |

| Assisting students’ well-being through immersive qualities of the outdoors. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lauterbach, G. “Building Roots”—Developing Agency, Competence, and a Sense of Belonging through Education outside the Classroom. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111107

Lauterbach G. “Building Roots”—Developing Agency, Competence, and a Sense of Belonging through Education outside the Classroom. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(11):1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111107

Chicago/Turabian StyleLauterbach, Gabriele. 2023. "“Building Roots”—Developing Agency, Competence, and a Sense of Belonging through Education outside the Classroom" Education Sciences 13, no. 11: 1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111107

APA StyleLauterbach, G. (2023). “Building Roots”—Developing Agency, Competence, and a Sense of Belonging through Education outside the Classroom. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1107. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111107