1. Introduction

In the international literature, it is well justified that frequent access to the natural environment has significant beneficial effects on children’s health, development and wellbeing [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This is particularly true in mitigating or coping with stress [

5], improving mental health [

6,

7], improving symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) [

8] and providing opportunities for physical activity and exercise [

9,

10]. Nature helps children to deal more effectively with their problems, think clearly and feel free and relaxed [

11]. In addition, higher levels of biodiversity around schools have been linked to better respiratory health [

12], vitamin D sufficiency [

13] and lower rates of vision degeneration [

14] in children. A study in Germany showed an inverse association between neighborhood greenness and insulin resistance in adolescents, which was attributed to the filtering of traffic air pollutants by vegetation and, as a result, reduced exposure of adolescents to air pollutants [

15]. Moreover, in younger children between five and seven years old, playing in a natural environment also proved beneficial, since it appears to increase creativity in their play and improve gross and fine motion skills, which are extremely important for their cognitive development [

16,

17].

However, many children in urban environments lack the opportunity for access to nature. Soga et al.’s [

18] study in Tochigi, Japan, which took place in a season when children’s use of nature is likely to occur frequently, found that more than 20% of children had never engaged in any type of nature-based activities in the previous month. Similarly, research in the UK showed that 12% of children under the age of 16 had not visited a natural environment in the previous 12 months [

19]. An interesting study was conducted in 2009 comparing the frequency of children’s use of natural spaces with the respective frequency of adults when they were children. The study reveals that less than 10% of children play often in natural places as opposed to 40% of adults when they were young. Furthermore, less than a quarter of children have visited a local natural space, compared to over half of the previous generation [

20]. This study points out that the current generation is increasingly disconnected from nature.

Children’s disconnection from nature may be attributed to diverse reasons, such as urbanization limiting the population’s access to green spaces, children having less free time for outdoor play than previous generations, or being more restricted than their parents. Parents are often reluctant to allow their children to explore wild natural areas because both, parents and children, have little familiarity with nature, and they are concerned about their children’s safety [

21]. Similarly, children are allowed to explore areas within close proximity due to increased fear of strangers and traffic [

22]. At the same time, children struggle every day to cope with an increasingly demanding (and therefore stressful) curriculum, which requires a significant part of their time [

21]. Furthermore, according to Moss [

23], the attraction and allure of screen-based digital home entertainment acts as a further barrier to children and young people’s engagement with outdoor recreation.

In order to bridge the gap between the benefits provided by the contact of children with nature and the lack of such contact, there has been in recent years a growing trend from schools to promote and support outdoor learning activities through access to green spaces, both for teaching and playing [

24]. According to Donaldson and Donaldson [

25], outdoor education/learning is education in, about and for the outdoors and represents a very broad range of activities. There is not a commonly accepted definition of outdoor education/learning, since there are great differences in culture, philosophy and conditions between countries and regions [

26]. However, for the purposes of this research, outdoor education and learning describe the same activity and this is defined as education that is provided in an open space. It is not used with its broader concept of out-of-class/school education, which refers to educational activities that take place outside the classroom/school, but not necessarily in an open space. In particular, outdoor education refers to a range of outdoor activities, such as playing, gardening, fieldwork, outdoor lessons integrated into the school curriculum, etc. [

25,

26], and it concerns short-time educational visits and day or multi-day educational excursions. As open spaces are considered the schoolyard, school neighborhood, natural environments, nature reserves, national parks and others; while school area is the built, semi-built, or open area that belongs to the school. For example, the school building, the schoolyard, a greenhouse, a vegetable garden, a sports field, etc.

The Scandinavian countries (i.e., Norway, Sweden, Denmark) are considered pioneer countries in this context and are often presented as examples of good practices regarding outdoor learning in preschool and school education [

27]. The foundations of Forest Schools, as a childcare institution, where children often spend all their kindergarten time outdoors, originate in Denmark and other Scandinavian countries [

28]. A similar trend is observed in other non-Scandinavian countries, where the outdoors is increasingly part of preschool and school education too, demonstrating the international nature of this interest [

29]. Hence, for instance, the Scandinavian Forest Schools approach has led to an increasing number of early childhood educators using it in England [

27]. Also, in Germany, in 2011, there were over 700 forest kindergartens, while more and more elementary schools and kindergartens focused on familiarizing students with the natural world [

30]. Additionally, in the USA, nature-based preschools have also proliferated over the past two decades [

31]. Furthermore, according to Waite [

26], research participants from Denmark, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Indonesia and Japan reported early years outdoor activities as occurring increasingly more often.

Outdoor learning, through fieldwork and outdoor educational visits, offers children opportunities to improve their memory and to learn and develop skills that are valuable for their academic development, as it relates not only to cognitive and behavioral development but also to their ability to concentrate and self-discipline [

32,

33,

34,

35]. These benefits have been proved for neurotypical children, as well as for children with ADHD [

36] and learning disabilities [

37]. Ulset et al. [

38] found a negative association between children’s inattention and hyperactivity and time spent outdoors at preschool age. Increasing time spent outdoors in nature can also enhance a child’s connection with nature and its emotional development [

39]. As a result, children engaged in learning outside the classroom have increased self-confidence and self-esteem, improved critical thinking [

40] and improved leadership and social skills [

41], as well as active citizenship skills [

42]. Furthermore, education outside the classroom fosters the inclusion of students with immigrant backgrounds [

43]. According to O’Brien and Murray [

44], children’s involvement with nature also provides them with sensory and intellectual benefits as it allows them to connect with and understand their environment. Students have the opportunity to observe, study, discuss and discover knowledge and ideas through the natural environment around them. In particular, the outdoor learning environment complements and enhances traditional learning, creating a curriculum that goes far beyond what students learn from a conventional textbook [

45,

46].

Despite the considerable amount of literature and research that has been conducted regarding the importance of children’s contact with nature through school activities, Southern Europe is rather underrepresented in the international literature, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first relevant study conducted in Greece. The aim of this study is to investigate whether primary and secondary schools are in fact in line with international trends. The objectives of the study are:

To identify the degree of teachers’ participation in providing opportunities for interaction with nature, in the context of the educational process and the degree of student’s participation in Environmental Education Programs (EEP).

To investigate how the schools perceive the possible effects of outdoor educational activities on students.

To investigate the effect of outdoor education activities on students’ performance and behavior towards violence and delinquency.

To characterize the educational situation in Greece to facilitate policy dialogue about expanding outdoor access via schools.

2. Methodology

The study employs a questionnaire to address its research questions and achieve its aim and objectives. The questionnaire is based on previous studies that have investigated similar aspects of the relationship between school activities, contact with nature and teachers/students’ perceptions. More specifically, the questionnaire developed by Bentsen et al. [

29], to investigate the participation of schools in Denmark in a program of outdoor education (udeskole), was taken into account when developing the current questionnaire. Similarly, the questionnaires developed in the studies by Waite [

47], Dilon & Dickie [

48], Scott et al. [

49], Connolly & Haughton [

50], Glackin [

51] and Walker et al. [

52] also contributed significantly in developing the questionnaire used in the study. Finally, the particularities of the Greek education system, such as the lack of any nation-wide program for promoting contact with nature through school activities and the long period of economic recession, were also taken into account when forming the questions. The questionnaire was created in Google Forms (see

Appendix A) and included the constructs and questions presented in

Table 1.

Permission to conduct research in schools was issued by the Greek Ministry of Education. Initially, an early version of the questionnaire was used in a pilot survey in 40 schools in order to test its reliability. The test was carried out using Cronbach’s Alpha internal consistency index and based on the results the questionnaire was corrected and adjusted accordingly. It was then e-mailed twice, once in December 2022 and again, one month later, in January 2023, to 8168 primary and secondary schools in Greece, attended by students aged between 6 and 18 years old. The questionnaire had to be answered by an appropriate representative, which could be the school’s principal, vice-principal, teacher, or relevant administrative staff from each school, who could provide valid data. In Greek schools, administrative staff are involved in the regular teacher meetings, in organizing outdoor activities, in keeping statistical data, in everyday correspondence and in a number of other activities that make them appropriate to fill in such a questionnaire. Furthermore, in some cases, schools also employ psychologists or social workers, who could also fill in the questionnaire, since they are involved in education activities and are responsible for monitoring student behavior. Unfortunately, most Greek schools are extremely understaffed by administrative and scientific staff, and this is the reason why the great majority of questionnaires were filled in by the other categories of potential respondents as we present below. All schools were informed by an attached letter about the purpose of the research and the legislation protecting the privacy of the research data. They were also informed that their participation in the research is optional and anonymous, and they can withdraw from the research at any time. The identity of the schools that participated in the survey as well as the institutional role of the respondents from each school are confidential.

The minimum required survey sample size was determined using Raosoft’s sample size calculator “

http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html (acceced on 29 June 2022)”. The acceptable margin of error was estimated at 5% and the tolerable confidence level at 95%. The response distribution chosen was 50% as it is the most conservative assumption. In order to collect the required sample size, it was considered appropriate to send the survey questionnaire to all the schools of the target population, that is, to the 8168 primary and secondary education schools attended by students aged between six and 18 years old. The required sample size was calculated at 367 schools, based on the reference population of 8168, which should be stratified spatially, by level of education and settlement type. The response rate was eventually 6.77%, as responses were received from 553 schools in total. Of these, 45 responses were removed because they were duplicates or contained unreliable data or were received from schools where attending students are not within the age range set. Consequently, 507 responses were considered valid and included in the analysis. The margin of error, for a confidence level of 95%, that was calculated from the collected sample was 4.219%. The answers were satisfactorily stratified both in terms of the education level (

Table 2), as well as in terms of the settlement type (

Table 3) and the region to which the schools belong (

Table 4). Conversely, the participation from private schools was extremely small (

Table 2). The majority of questionnaires (75.5%) were completed by school principals, 9.7% by vice principals, 14% by other teachers and only 0.8% by administrators and psychologists.

The response rate of 6.77% may seem rather low to form a representative sample of all primary and secondary schools in the country. Similar studies conducted in England [

47,

52] and Barcelona, Spain [

53] had obtained response rates between 7.4 and 26.9%. However, the target population in these surveys was smaller (from 324 to 4000 schools) and as a result, the response rate had to be higher in order to achieve the minimum required sample for the research to be considered reliable.

The reliability of the questionnaire was verified using the Cronbach’s Alpha internal consistency index, which was greater than 0.7 for each construct’s subscale. The validity of the constructs of the questionnaire was checked by Principal Component Analysis (PCA). In particular, the convergent validity and the discriminant validity were examined and confirmed for each construct separately, as the items that form the same concept demonstrated high correlation coefficients between them in PCA, and items measuring different concepts were not related to each other in PCA. In addition, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and the Composite Reliability (CR) indices were calculated, since for convergent validity to be valid, it must be true that AVE > 0.5, CR > 0.7, and CR > AVE, and for discriminant validity to be valid, it must be true that square root of AVE for each component is greater than the correlation of the components [

54]. These conditions were verified for all the components of the constructs of the questionnaire. During data processing, continuous variables were checked for normality of distribution, and it was found that the null hypothesis was not verified (

p > 0.05), and the distributions were not normal. For this reason, the non-parametric Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis Tests and Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient were employed during the inductive statistical analysis of the data. The statistical processing of the survey data was carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 software.

3. Results

The results of the statistical analysis show that on average, about 3 out of 10 teachers in Greece choose outdoor activities during the educational process, while in half of the schools, up to 2 out of 10 teachers provide outdoor learning opportunities to their students. In particular, the percentage of primary education teachers who provide outdoor learning opportunities to their students is statistically significantly greater than that of secondary education teachers (

Table 5). Similarly, a greater percentage of teachers provide outdoor learning opportunities to the students of special education schools than in general education schools (

Table 5). No statistically significant difference was observed between general and vocational high schools (Z = −0.365,

p = 0.715) or between middle schools (gymnasium in Greek terminology, where students 13–15 years old attend) and high schools (lyceum in Greek terminology, where students 16–18 years old attend) (H = 21.285,

p = 0.764).

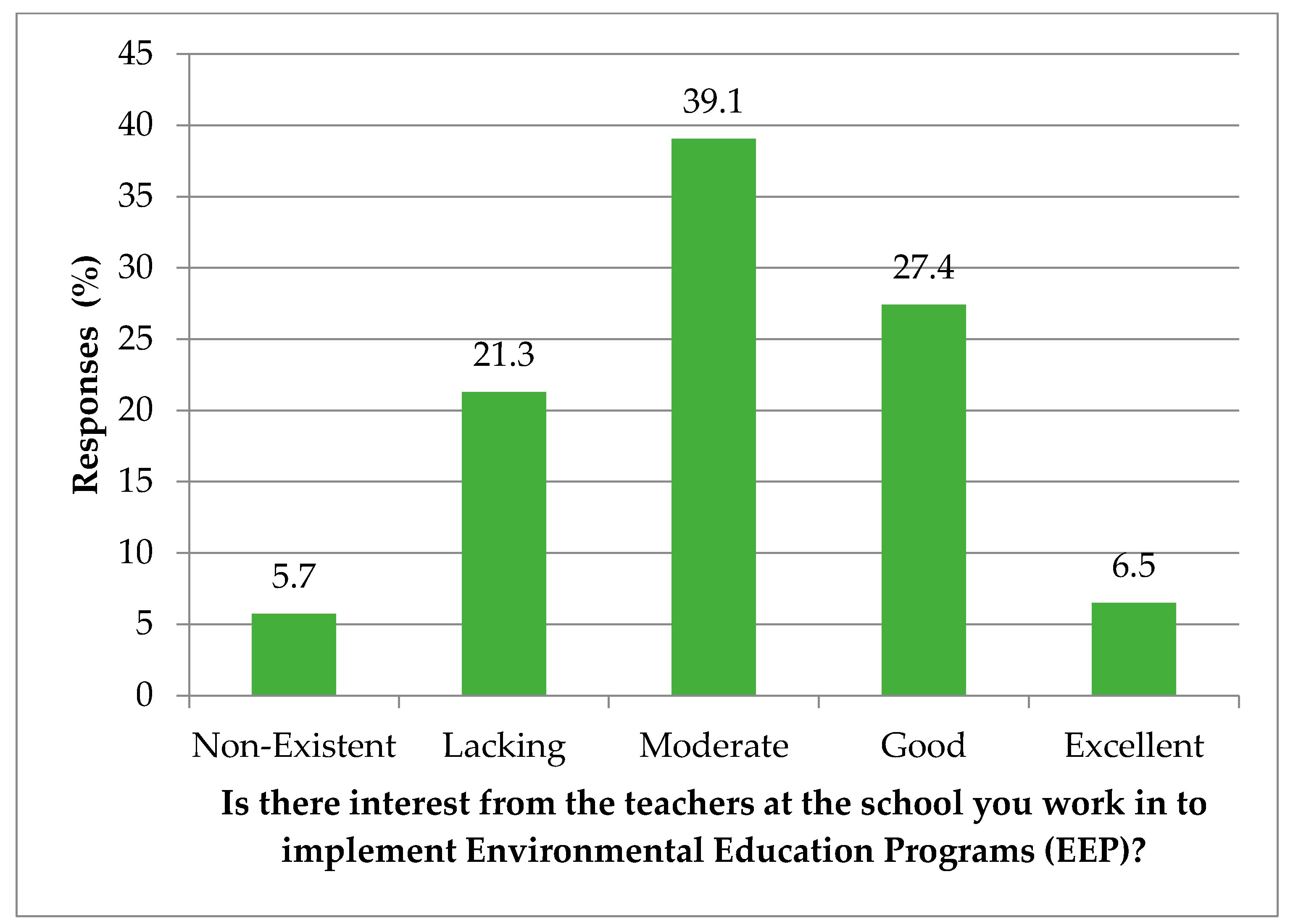

In addition, 33.9% of schools surveyed stated that there is excellent to good interest from teachers in the school to implement EEPs, while 39.1% stated that there is moderate interest. Unfortunately, 27% of schools stated that teachers’ interest in the implementation of EEPs is lacking or non-existent (

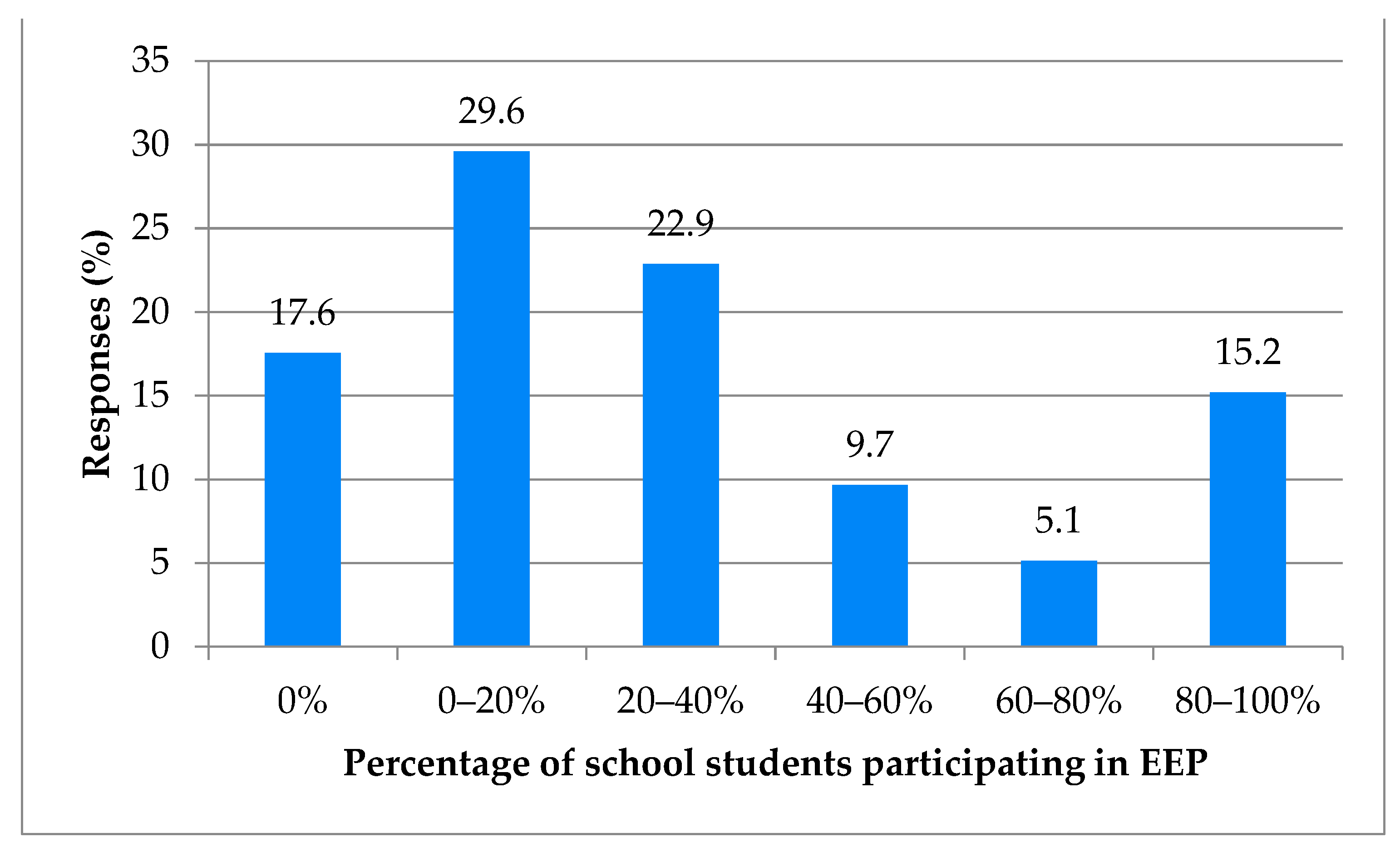

Figure 1). Moreover, 17.6% of schools do not implement EEPs as they state that none of the students participate, while in 52.5% of schools up to 40% of students participate in EEPs (

Figure 2).

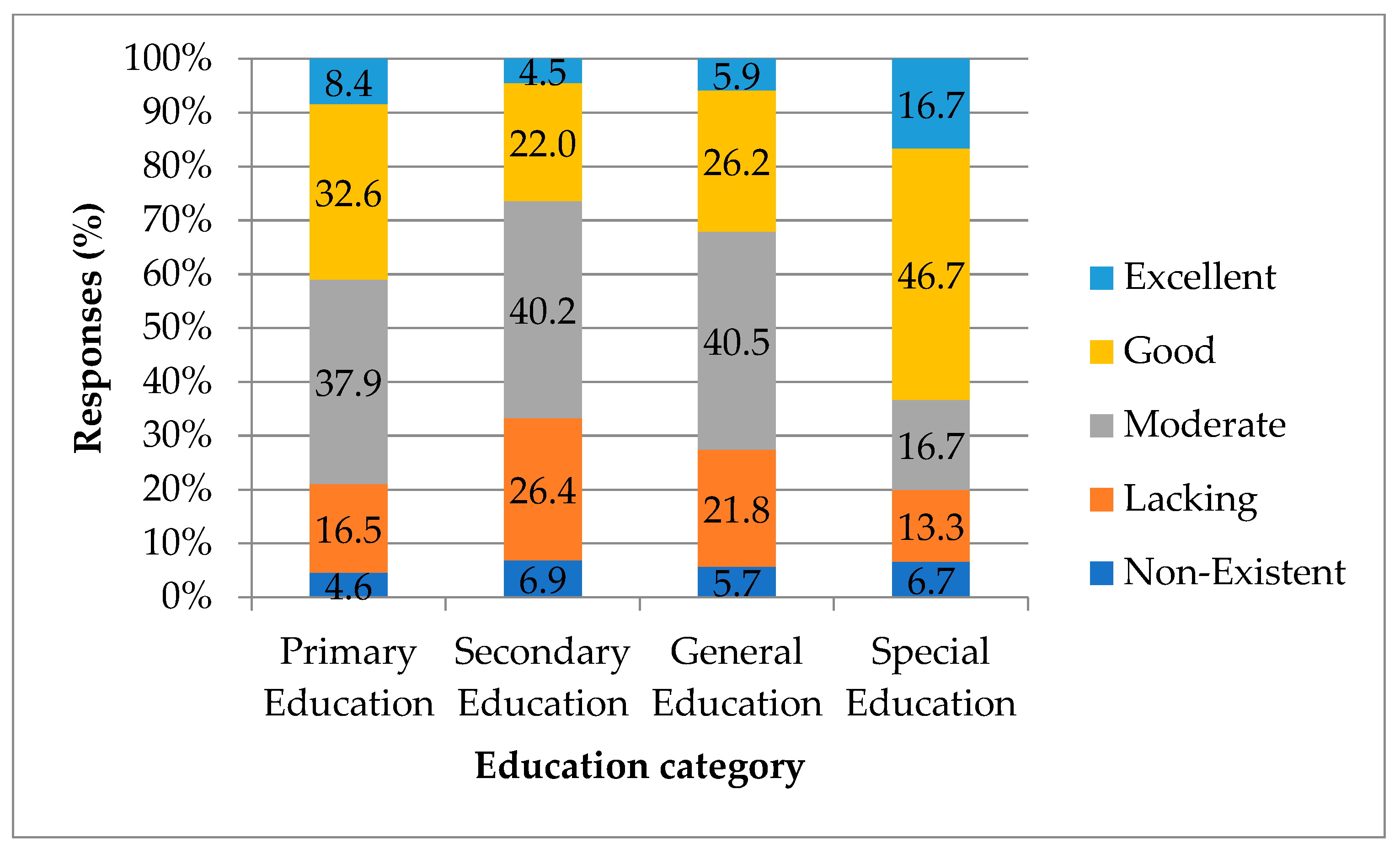

The statistical analysis shows that primary education teachers again show a greater interest in the implementation of EEPs (Z = −3.89,

p < 0.01) (

Figure 3). Conversely, no statistically significant difference emerged between the teachers of middle and high schools (H = 18.018,

p = 0.312), or among the teachers of general and vocational high schools (Z = −1.066,

p = 0.286). However, the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney U test showed that there is a statistically significant difference between general and special education teachers (Z = 2.764,

p = 0.006), with the latter showing a greater interest in the implementation of EEPs (

Figure 3).

The exact same trend as with teachers is observed for students with more primary education students participating in EEPs, compared to secondary education students. No statistically significant difference emerged between middle and high school students (H = 36.278,

p = 0.154), or between general and vocational high school students (Z = −0.323,

p = 0.747). A statistically significant difference between the percentage of general education students and those of special education was observed with the latter participating in EEPs to a greater degree (

Table 6). A similar trend between teachers and students that is observed here is rather anticipated since when more teachers are involved in EEPs it is reasonable that more students participate also. This is confirmed by the Spearman’s rho non-parametric correlation test, where a moderately positive and statistically significant correlation emerges between teachers’ interest in the implementation of EEPs and the percentage of school students who participate in them (rho = 0.538,

p < 0.01).

3.1. The Number of School Visits to Locations of Direct or Indirect Contact with Nature in Relation to the Number of Teachers Involved in Outdoor Education

A weak but statistically significant positive correlation emerged between the percentage of teachers who provide outdoor learning opportunities to their students and the number of annual visits to (a) natural spaces, (b) urban and peri-urban green spaces and (c) indirect nature education spaces. Furthermore, a statistically significant positive correlation emerged between the total number of visits outside the school area (visits to areas of general interest and not only to areas related to nature) and the different types of educational nature-related visits (

Table 7).

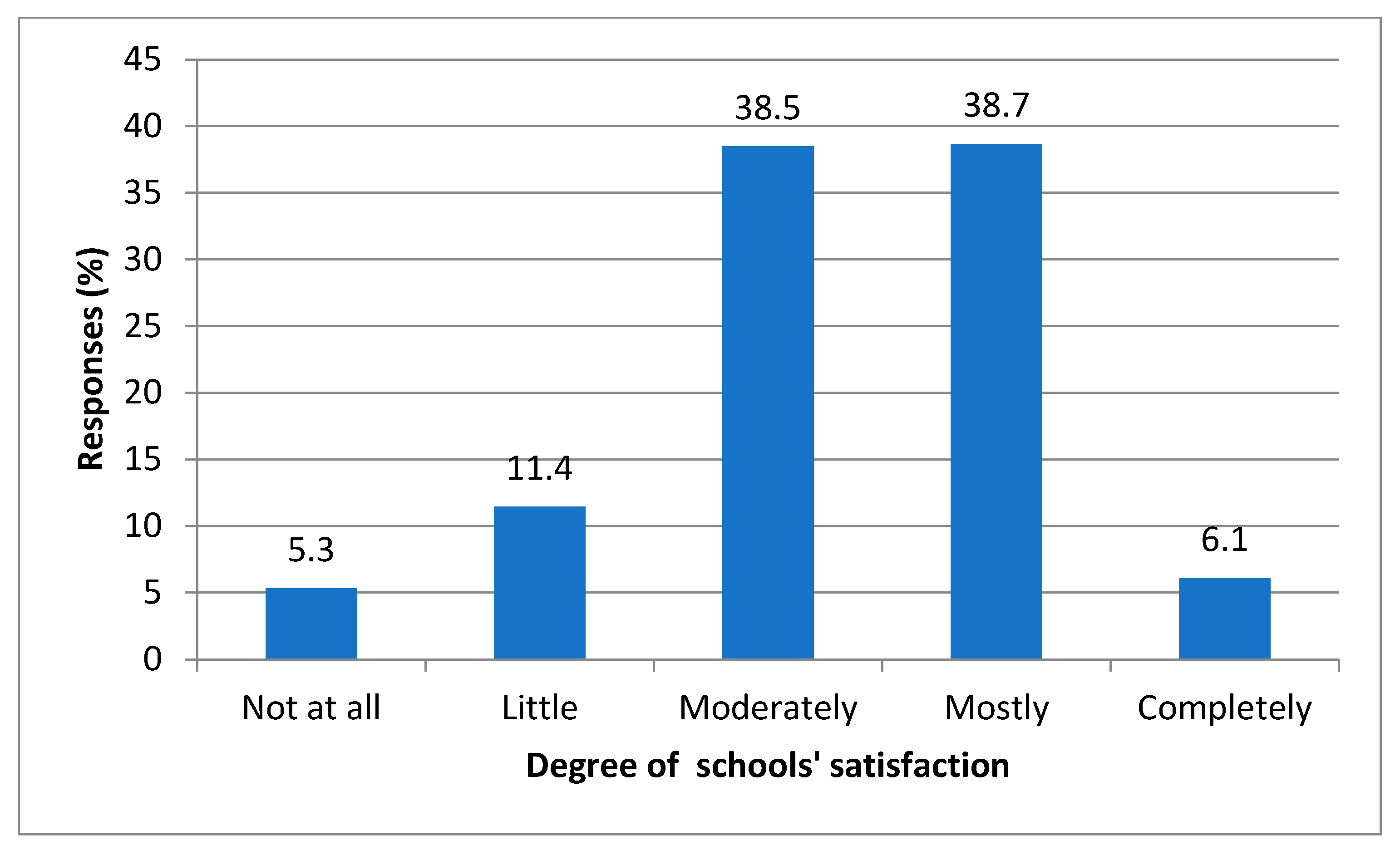

3.2. Degree of Schools’ Satisfaction with the Number of Visits Organized by the School to Locations outside the School Area

A percentage of 83.2% of the participants stated that their schools were moderately to completely satisfied with the number of visits organized by their school to locations outside the school area. The average number of educational visits during the academic year, which in Greece lasts for nine months, was estimated at approximately nine. Meanwhile, only 16.8% of the participants stated that their schools are little or not at all satisfied with the number of trips organized by the school to locations outside the school area (

Figure 4). These results are common for all school categories and in all regions of Greece since no statistically significant difference between them was observed (

p > 0.05).

3.3. The Frequency of Use of the Schoolyard, the Frequency of Nature-Related Activities and the Participation of the School in EEPs in Relation to the Number of Teachers Involved in Outdoor Education

The percentage of teachers providing opportunities for outdoor learning is also positively correlated with (a) the frequency of using the schoolyard for educational activities, (b) the frequency of nature-related activities inside or outside the school area and (c) the participation of students and teachers in the implementation of EEPs (

Table 8). Therefore, the more teachers show an interest in outdoor education, the more activities in nature or through nature and for nature are carried out, the schoolyard is better used educationally and the school community is more likely to implement EEPs.

3.4. The Perceived Benefits Students Receive from Outdoor Educational Activities in Nature

As the activities related to nature increase, so do the perceived students’ benefits, as demonstrated in

Table 9. Also, a statistically significant positive correlation emerges between teachers’ interest in the implementation of EEPs and the valuable knowledge, skills and abilities that students can obtain from them (

Table 10).

The data regarding the degree of schools’, teachers’ and students’ involvement in outdoor learning activities and participation in EEPs were analyzed in relation to the reported academic achievement by students as well as their behavior (

Table 11). The results indicate a statistically significant positive relationship between the number of students with excellent academic performance and increased involvement of the school in outdoor learning activities and EEPs, especially when these occur in nature education sites where students can experience indirect contact with nature (e.g., zoos, museums, aquariums). In contrast, a statistically significant negative correlation was found between the number of students who fail to be promoted to the next grade, due to low performance, and the number of teachers who provide opportunities for outdoor learning activities as well as the number of students who participate in EEPs. Similarly, the percentage of students who fail to be promoted due to insufficient attendance and the number of students who drop out of school are also negatively correlated with several parameters that indicate an increased involvement of schools in activities that bring students closer to nature. Of particular importance is the negative relationship that was identified between the number of teachers who provide outdoor learning opportunities and the reported levels of incidents of violence and delinquency.

4. Discussion

As noted in the introduction, scholars increasingly acknowledge the invaluable and irreplaceable contribution of outdoor education to the development and education of students across all age groups. This recognition is particularly pertinent today as children progressively distance themselves from the natural environment and immerse themselves in the virtual realities offered by digital technology. Consequently, the potential value of outdoor education is heightened, underscoring a growing imperative for its widespread implementation.

Nevertheless, the results of this research indicate that in Greece, the percentage of teachers who choose outdoor activities during the educational process is rather low. Specifically, in 50% of primary schools less than 40% of teachers are involved in outdoor education, while in half of secondary education schools only up to 15.4% of teachers are involved in outdoor education learning activities. Furthermore, in half of special education schools, up to 4 out of 10 teachers educate students outdoors, while in 50% of the country’s general education schools, 0 to 2 out of 10 teachers use this education method. So, in general, it was observed that relatively more teachers of primary schools and special education schools participate in this type of learning approach. This may be attributed to the effectiveness of pedagogical approaches during early childhood that incorporate playful activities in nature, emphasizing movement and interaction [

55]. Additionally, outdoor play has been shown to significantly improve functional behavior in children with ADHD [

36]. Despite these benefits, most teachers still opt to avoid outdoor education.

The study also found that the percentage of teachers providing opportunities for outdoor learning was positively correlated with the number of nature trips conducted by the school and with the frequency of activities conducted in, through and about nature. Also, the schoolyard is better used educationally and the school community is more activated for the implementation of EEPs in schools where more teachers show an interest in outdoor education.

It appears that school communities consider that outdoor activities and EEPs benefit students, as they can be more easily included in the educational process. This is particularly true for disadvantaged students, who commonly are not interested in and are not effectively approached by traditional teaching in the classroom. Outdoor activities are regarded to strengthen the students’ mental health, self-esteem, self-confidence and independence, as well as their self-control and their ability to assess risks, understand the consequences of their actions and survive in adverse conditions. They are also considered to reduce the feelings of anger and aggressive behavior of students, to improve the social and intercultural relations of the school community and the ability of students to communicate and cooperate with each other. Also, in a wider context, school communities believe that relationships are established with the professional world, bonds are created with the local community and finally, students connect education with real life, a fact that creates additional motivation for their participation in the educational process. Hence, as their interest in the educational process increases, their mental clarity and ability to concentrate improves, both in neurotypical and ADHD children, their cognitive performance increases, their gross and fine motor skills improve and their imagination, inventiveness and creativity are enhanced. These results are well aligned with the broader literature in the field: Sahoo and Senapati [

36], in their research, indicate outdoor play as an effective therapeutic process for the development of functional behavior in children with ADHD; Czeisler [

56] claims that even just exposure to sunlight is particularly beneficial for children’s physical and mental well-being as it affects their circadian rhythm and sleep; McCormick’s [

7] literature review found that children’s frequent access to green spaces was associated with improved general health, mental well-being and cognitive development, as it promotes restoration of attention, memory, teamwork, self-discipline, relieves stress, improves ADHD behaviors and symptoms and was even associated with higher test scores. Related to the last point, it is important to note that children who do not get enough sleep during the day become hyperactive and find it difficult to focus their attention. Therefore, sleep deprivation can be mistaken for ADHD, which is an increasingly common medical pathological condition [

56]. School outdoor activities based on the research observations can overcome such negative effects.

In addition, according to the respondents, schools tend to believe that soft skills and abilities, such as awareness of environmental issues, critical thinking, problem-solving and active participation, are improved in students, through outdoor activities in nature and EEPs. Such skills and abilities are not only valuable for themselves but also for society and the environment. Similarly, Otto and Pensini [

57], in their research in five schools in Berlin, found that increasing participation in nature-based environmental education activities was positively related to students’ ecological behavior, through increasing their knowledge about the environment, but mainly through their connection with nature. Also, the literature review of Ardoin and Bowers [

55] found that the main outcomes of environmental education are the development of environmental literacy and the cognitive, social and emotional development of children.

Based on the observations made in this study, there is a strong perception in teachers that their involvement in outdoor activities related to nature is very important with significant positive effects on students. This is evident from the fact that the participation of teachers and students in outdoor activities and EEPs was positively correlated in the present research with the number of students who had excellent performance in school, and negatively with the number of students who repeated the same grade because they were not promoted or students who dropped out and with the incidents of violence and delinquency within the school community. Similarly, Ruiz-Gallardo, Verde and Valdés [

58] found that students of a high school in Spain showed significant academic success, following educational programs based on activities in the school garden. In particular, the positive correlation between the number of (a) educational visits to a natural place, (b) visits to places of indirect contact with nature and (c) activities interacting with the school nature, with the percentage of students with excellent performances, may be due to the richness of stimuli that engage children in outdoor activities, which stimulate their interest, attention and perception and improve their memory. Also, a very important and useful observation, which emerges from the results of this study, is that visits to natural places and frequent use of the schoolyard can reduce the percentage of non-promoted to the next grade students due to absences, as well as those who leave the school. Moreover, the students at risk of dropping out the school seem to benefit even from visits to places of indirect contact with nature. This is likely because outdoor education is more inclusive than traditional classroom teaching, offering students a greater sense of freedom, autonomy and initiative. It is not only more enjoyable but also more engaging, as it connects to real-life experiences and addresses students’ personal interests and concerns through experiential learning. This observation is very important and useful, because teachers worry about the frequent absence of students from classes and the possibility of dropping out of school, and are looking for new teaching methods and techniques to create a more attractive school environment for all students. Furthermore, individual school activities involving interaction with nature within the schoolyard appear to reduce student delinquency. This can be attributed to the fact that such activities foster a connection to the school environment, leading to increased respect for the space. Also, the activities that involve students in direct contact with nature were negatively associated with incidents of violence in the school community. This may be because such activities, characterized by experiential learning, interaction, cooperation and teamwork, help to create stronger bonds and foster respect and solidarity among students, as well as between students and teachers.

Despite the representative number of schools that participated in this research, there are some important limitations in the study. The first arises from the fact that the effect of outdoor activities on students and the benefits they have was not assessed by an objective and actual measurement that could be made using methods employed, for instance, in psychology or other relevant sciences such as ergotherapy. It was rather assessed based on the perceptions that the schools’ representatives, primarily principals, have on these benefits, which may result from personal experience as well as from discussions with teachers who participate in such activities. Furthermore, this approach may lead to some kind of confirmation bias, assuming that schools that tend to promote outdoor learning activities may also tend to overestimate the benefits of such activities. Although an objective assessment of such benefits would increase the validity of the presented results, we sincerely believe that our approach also provides valid and informative results. A second limitation of the study is that schools that tend to organize more outdoor activities may also tend to consider them more beneficial for the students. While we know the number of outdoor activities organized by each school, we could not find an appropriate method to correlate the number of visits with the perceived benefits. This limitation prevents us from accurately determining whether the positive relationship is due to bias or genuine benefits from outdoor activities. Finally, this study does not report on the reasons behind the current status of schools’ participation in programs and activities that bring students closer to nature and the environment. This is an important research question and will be addressed by the research team in follow-up research.