Abstract

Women’s universities were established in post-war Japan to fill the gender gap in higher education. Although they attract fewer students today than in the past, they account for nearly 10% of all universities nationwide. This study focuses on the diploma policies (DPs) that all universities in Japan are required to publish and explores the characteristics of education at women’s universities by comparing the DPs of 22 women’s and 59 co-educational universities. The DP content was analyzed using a cross-tabulation search engine employing text-mining. The results indicate that the DPs of women’s universities highlight their priority to foster economically sustained women, which reflects their founding purpose of empowering women. Although both women’s and co-educational universities emphasize their relationship with society, the latter seem to view society as something their graduates can create and develop, while the former regards it as given or changing. Moreover, women’s universities appear to emphasize that their graduates play an active but not a leading role in society. This could be an indication of gender inequality in the social, economic, and political realms of Japan. Considering Japanese society is becoming globalized and diverse, future research should focus on how global values and competencies manifest themselves in DPs.

1. Introduction

Women’s universities were established in postwar Japan to fill the gender gap in higher education by empowering women [1]. Currently, women’s universities attract fewer students than in the past, as female students prefer co-educational institutions that offer a variety of careers and business-oriented departments [2,3,4]. Nevertheless, women’s universities in Japan account for nearly 10% of all universities nationwide; they are concentrated in metropolitan areas, where one-third of universities are for women only [5]. Assuming no gender differences in potential academic achievement and professional performance in today’s modern society, the generic skills or competencies that each university seeks to foster should not depend significantly on whether it admits only women. This study explores and compares the characteristics of education at women’s universities to those of co-educational universities by analyzing the descriptions of their graduates’ attributes found in the diploma policies (DPs).

1.1. Women’s Universities in Japan: A Historical Overview

Higher education for women began in 1872 with the promulgation of the Education System Ordinance. Modern Japan prioritized higher education for men over that of women, reflecting the Confucian view of gender among the feudal warrior classes that led the Meiji Restoration Government [6]. The 1879 Education Ordinance adopted single-sex education in principle [7], which was promoted at higher grade levels, and women’s education was mostly limited to private schools [6]. Education reflecting different gender roles was deemed effective, and the purpose of women’s education was to raise good wives and wise mothers; thus, sewing and housekeeping were introduced to female students [6]. This explains why women’s higher education was rooted in home economics.

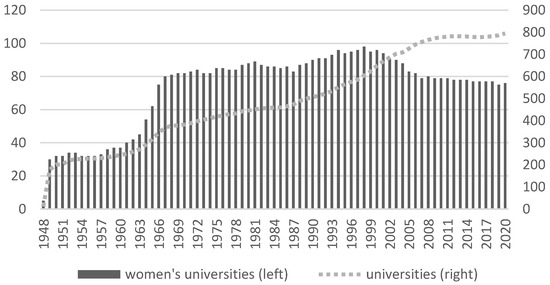

At the beginning of the 20th century, most public educational institutions for women aimed at training teachers, and a few private women’s colleges were established [7]. Under the 1948 education system, female students were admitted to co-educational universities, which were effectively for men only [8,9]. Five women’s universities were founded in 1948; since then, the number of women’s universities has increased. They peaked at 98 in 1998, a few years after the Gender Equal Employment Opportunity Law, and then gradually declined (Figure 1). As society has come to value diversity and inclusiveness, female students have chosen co-educational universities that offer a wider variety of subjects. Although the eligible student population of 18-year-olds has experienced a long period of decline beginning in 1992, the number of universities, both women’s and co-educational, has increased. This competition has made it difficult for women’s universities to recruit students, and some have decided to revitalize by becoming co-educational or to close [9]. While many universities in Japan face bleak futures with the decline in the birth rate outpacing the rate of increase in higher education, women’s universities face a tougher challenge in recruiting students than co-educational universities.

Figure 1.

Trend in numbers of universities [10].

The latest statistics show a decrease in the number of female students majoring in the humanities, offset by an increase in the number of students majoring in health, particularly nursing (Table 1). Recently, the government has encouraged female students to study science and engineering, as these subjects have a low percentage of female students and the student gender balance is disproportionate [11]. Accordingly, some women’s universities have established engineering and data sciences departments [12].

Table 1.

Composition of female students by major (based on the Basic School Survey [13]).

1.2. Three Policies for Quality Assurance of Higher Education

Globally, higher education reform emphasizes learning outcomes and the systematization of degree programs; a recent government policy for university reform in Japan has been modeled on policies in the UK [14]. In April 2017, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) required all universities in Japan to formulate and publish “three policies”: admission policy (AP), curriculum policy (CP), and diploma policy (DP) [15]. Although many universities had already formulated these policies in response to MEXT’s recommendations, MEXT claimed that many policies were superficial and that the three policies were unrelated to each other [15].

These three policies were institutionalized with reference to “programme specifications” in the UK [14], which provide “a concise description of the intended learning outcomes of a Higher Education (HE) programme, and the means by which the outcomes are achieved and demonstrated” [16] (p. 3). The programme specifications include “criteria for admission to the programme”, “aims of the programme”, “relevant subject benchmark statements and other external and internal reference points used to inform programme outcomes”, “programme outcomes: knowledge and understanding; skills and other attributes”, and “teaching, learning, and assessment strategies to enable outcomes to be achieved and demonstrated” [16] (p. 6).

In 2017, MEXT made it mandatory for universities to clarify how their programs cultivate the attributes necessary for students to meet the needs of society, and for teaching staff to provide education recognizing the particular attributes their subject is responsible for and to collaborate with staff in other subjects. Based on the DP, the curriculum, content of education, and appropriate pedagogy should be clarified in the CP, and academic achievement for applicants to enroll in the program should be provided in the AP. The educational program is implemented according to these policies and evaluated for improvements in light of the policies. This process is believed to underpin quality assurance and reform cycles [15].

Descriptions of the three policies are presented in Table 2. Universities may plan and update these policies at either the program or department level; some set three high-level policies that are used by programs/departments to develop their individual policies.

Table 2.

Descriptions of the three policies [15] (p. 3).

1.3. Analysis of Diploma Policies

Following the institutionalization of the three policies in recent years, researchers have sought to understand the characteristics of particular universities or departments by analyzing their respective DPs, frequently through quantitative text analysis. Kurihara analyzed the DPs of liberal arts departments in 44 universities nationwide by extracting and clustering frequently occurring words [17]. Liberal arts offered as specialized education (in a department of liberal arts as opposed to general education courses) is characterized by the acquisition of learning skills, such as information literacy, communication skills, and practical English proficiency, in addition to interdisciplinary experiences and critical thinking skills. DPs in the liberal arts departments of women’s universities tend to include elements of vocational education because of their historical background as home economics departments [17].

Horiuchi focused on terms related to “sustainable” in tourism department DPs, and presented co-occurrence networks [18], finding that DPs rarely refer to “sustainability” despite the fact that both the tourism industry and education in tourism departments value sustainability (i.e., sustainable tourism). Currently, when universities compete to attract potential students, easy-to-understand indicators such as close links to industry and a high percentage of employed graduates are preferred, making it difficult to include an ideal but abstract concept of “sustainable tourism” in DPs [18].

Kubota and Ikeda analyzed the co-occurrence networks of six clusters generated from the DPs of 189 nationwide professional social welfare training courses [19]. Because these courses were also offered in disciplines other than social welfare studies, the differences in learning outcomes between social welfare studies and other disciplines made it difficult to relate the latter to the learning outcomes for social welfare professionals in DPs. Nakagama and Yoshimura analyzed DPs and liberal arts education (in general education courses) in universities with nursing majors [20]. They compared the DPs of 10 universities established before 1991, when the Ministry of Education relaxed regulations on establishing universities, and those of 13 nursing colleges established after 1991. The DPs of the pre-1991 universities included “solution”, “diversity”, and “information”, while the post-1991 colleges included “nursing”, “acquire”, “community”, and “attitude”. Pre-1991 universities emphasized developing basic learning skills, while post-1991 colleges used liberal arts education as the basis for learning nursing practice [20].

The analyses in the above studies all used KH Coder [21], extracted frequent words, and plotted co-occurrence networks. However, Ogashiwa et al. [22] computed term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF–IDF), which looks for characteristic terms based on importance rather than just frequency of occurrence in a document. Words with high TF–IDF scores were extracted from the DPs of departments with “community” in their names. Although each department had a community-related name, some departments emphasized “community” in their DPs and others did not, which was considered to reflect differences in each department’s priorities and strategies in relation to community.

Moriyama analyzed messages published online by 69 presidents of women’s universities to explore how they addressed social missions, educational goals, and women in modern society [23]. The presidents’ messages referred to “improving the status of women through gender equality and democracy”, “contributing to society”, and “producing active professionals in society or graduates who play their role in households and communities”, and emphasized the “social and economic independence of women” (pp. 6–7). Some keywords associated with the mission of women’s universities were “human resource development”, “new era”, “responsibility”, “tolerance”, “global perspectives”, “leadership”, “high level of expertise”, and “self-realization”. Moriyama predicted that the raison d’être for women’s universities may become less important in a gender-equal society, although equality in some numerical indicators is not sufficient. She stated that women’s universities must continue to monitor the status of women in society and consider the conditions necessary for true gender equality.

Okada compared the most frequent terms in the founding philosophies of 66 private women’s universities with those of 139 co-educational universities nationwide [24]. Co-educational universities emphasized development of society and industry and cultivation of international and creative human resources, with “society”, “international”, “create”, “technologies”, and “development” as keywords. Women’s universities were established to cultivate humanities characterized by “love”, “cultivation of character”, “Christianity”, “autonomy”, “dedication”, and “sensitivity”.

Recently, Shibata and Fukaya extracted frequently occurring terms and presented co-occurrence networks for founding philosophies to capture the characteristics of women’s universities in Japan and the US [25]. Women’s universities in Japan emphasized education in human nature, where students had generous spirits and were well-educated to play active roles in society and contribute to the community. Although “society” was also seen in women’s universities in the US, those universities highlighted students’ leadership in global society.

Research on women’s universities in Japan has not been able to escape the “raison d’être” debate [26], and their founding and educational philosophies have been analyzed in comparison with co-educational universities. However, mission statements can be produced in any way, and regardless of a convincing raison d’être, some universities will disappear if students do not choose them. Therefore, research on women’s universities should focus on education and its impact on students [26]. An analysis of DP highlights the educational aspects of this issue.

1.4. Objective of the Study

This study analyzes the characteristics of education at women’s universities. It aims to examine the learning outcomes and graduate attributes described in the DPs of women’s universities and to explore the differences between the DPs of women’s and co-educational universities. The research questions are as follows:

- What distinct educational values and priorities are highlighted in the DPs of women’s universities in Japan?

- In what ways do the DPs of women’s universities in Japan differ from those of co-educational universities?

2. Materials and Methods

The data comprised the DPs of 81 universities, which are public and accessible online. Since the majority of universities in Japan are private, this study utilized private universities as the data source.

First, using a website specializing in university information [5], out of 208 universities in the Tokyo metropolitan area (Tokyo, Kanagawa, Chiba, and Saitama), 106 universities were identified as private. Professional and vocational universities, single-department colleges, and universities specializing in disciplines such as science, engineering, and health were excluded. Furthermore, after browsing individual university websites, 25 universities without university-level DPs were excluded. DPs comprising 815 sentences (594 from co-educational and 221 from women’s universities) were collected from the websites of 81 universities (59 co-educational universities and 22 women’s universities, Appendix A). Itemization was counted as a sentence. All data were collected and analyzed in Japanese, and the results were translated into English.

This study adopted quantitative text analysis to examine characteristics of DPs. To expedite the analysis, this study used a cross-tabulation search engine based on the TF–IDF evaluation customized by Monolithic Design Co. Ltd. TF–IDF is a text mining method used to evaluate the importance of a certain term appearing in target documents and is effectively used to extract words that characterize documents (feature words) [22]. TF refers to the frequency of a word in documents; if the word occurs frequently in documents (high TF), it is considered important. IDF indicates the number of documents that use a word. Words that appear frequently in several documents are considered less important (low IDF), whereas words that rarely appear in a document have high IDF. TF–IDF is an index obtained by multiplying TF and IDF [27].

TF–IDF = TF (frequency of words in documents) × IDF (rare frequency of words)

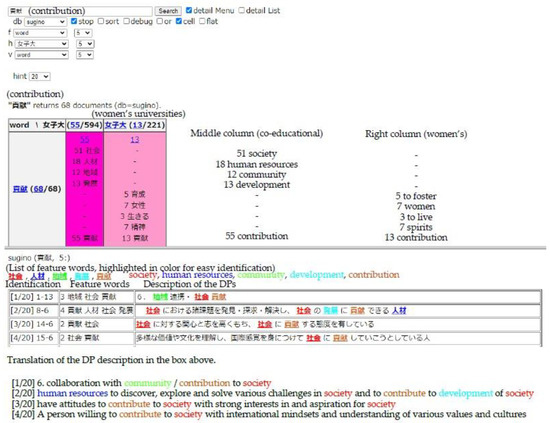

The cross-tabulation search engine sorts characteristic keywords using the TF–IDF score and lists other characteristic keywords that appear in words with high TF–IDF scores (Figure 2). The DPs of women’s universities and co-educational universities were grouped separately for a comparative analysis. Upon entering any word(s) in the search field (e.g., “contribution”), the left column shows the number of times the searched word (contribution) appeared in the document as a feature word with a TF–IDF value (68 times). The DPs are analyzed based on the number of universities that use the specific words and the word frequencies in the DPs, utilizing the search engine’s detail list function. The middle column lists the feature words related to the given word(s), that is, words appearing with the searched word(s) in the DPs of co-educational universities, and the right column lists those in the DPs of women’s universities. The lower part of the search engine screen shows the actual sentences in which these words appear, making it possible to examine their context. This overcomes the TF–IDF analysis limitation of being unable to check context and co-occurrences [27].

Figure 2.

Cross-tabulation engine.

3. Results

The first subsection provides an overview of the DPs of women’s universities in response to the first research question, followed in the second subsection by those of co-educational universities. Finally, in the third subsection, the DPs of women’s universities are compared to those of co-educational universities to answer the second research question.

3.1. Diploma Policies of Women’s Universities

Of the 22 women’s universities, 14 (63.6%) use “women” in their DPs, and the word appears 18 times. The contexts where the word “women” is used are categorized along three dimensions. The first is descriptions of “independent” and “autonomous” women, highlighting economic independence. The keyword for the second category is “contribution”, as in women who “contribute to creating culture and wellbeing of mankind” and “contribute to solving challenges of society”. The last is “women with rich sense of humanity”. Each category is referred to four to five times.

Table 3 shows frequent words in the DPs of women’s universities. All the women’s universities refer to “society”, which is the most frequent word in their DPs. In context, it is often used in descriptions of the society where their graduates will belong: “modern society”, “better society”, and “globalizing society”. Contributions to and participation in society are also mentioned: “contribute to society”, “serve society”, and “social responsibility”.

Table 3.

Frequent feature words (women’s universities).

The next most frequent words are “ability (chikara)” and “capability (nouryoku)”. Over 80% of the DPs of women’s universities include these words, which are often used interchangeably in Japanese. However, there appears to be a certain tendency. While ability is referred to in the “ability to think logically” or “critically” and the “ability to put (learning) into practice”, capability is often used when the DPs list capabilities: “the following capabilities”, “these capabilities”, and “attributes and capabilities”. In addition, “capability to communicate”, “linguistic capability”, and “capability to solve problems” are specifically mentioned.

Although less frequently used than those two words, over 90% of the women’s universities have the word “specialized” (or “expertise”) in their DPs. It is overwhelmingly used as “specialized knowledge”, with some examples “with expertise” and “high expertise”. Some universities refer to the level and range of “knowledge”: “advanced knowledge”, “various knowledge”, and “extensive knowledge”.

Exploring the contexts in which “acquire” is used highlights what the women’s universities expect their students to acquire as educational outcomes. In Japanese, both “minitsukeru”, literally meaning “to put on”, and “shuutoku”, “to learn and acquire”, can be translated as “acquire”. The former sounds softer and is used in spoken Japanese, while the latter tends to appear in written texts. While “minitsukeru (acquire)” takes various objects such as “attributes and capability”, “attitudes”, and “a good education”, “shuutoku (acquire)” appears most often with “credits”, meaning to take credits (necessary to graduate).

3.2. Diploma Policies of Co-Educational Universities

This subsection presents an analysis of the DPs of co-educational universities as shown in Table 4 and how these frequent words are used.

Table 4.

Frequent feature words (co-educational universities).

Here, “society” is the most frequent word and also the word mentioned by the highest number of co-educational universities, as 55 mention it in their DPs. All four of the 59 universities that do not use “society” have short DPs of an introductory nature, leaving the details to the departmental DPs.

The contexts in which “society” appears mostly relate to contribution: “contribute to development of society”, “contribute to local or international community”, “have social responsibility”, and “play a leading role in society”. The word “shakai-jin”, literally “society people”, meaning people who are members of society with jobs, appears in “responsibility as ‘shakai-jin’”, “active ‘shakai-jin’”, and “basic competencies as ‘shakai-jin’”. “Participation in society” is mentioned only twice.

Just under 90% of universities’ DPs mention “knowledge”, which appears overwhelmingly in the phrase “knowledge in specialized fields”. Other instances are “knowledge and skills”, “extensive knowledge”, and “basic knowledge”. “Specialized” is another popular word among co-educational universities. It is mostly seen in combination with knowledge—“specialized knowledge”—and, in some instances, modifies “expertise”.

“Ability” and “capability” also appear frequently in co-educational universities’ DPs. There are references to various kinds of abilities such as “ability to think logically, critically”, “ability to judge”, “ability to find and solve problems”, “ability to collaborate”, “ability to work with others”, “ability to develop career”, “ability to live better”, “ability to go beyond border”, and “ability to contribute to creating and maintaining groups with people of various backgrounds”. “Capability” is often used in a phrase introducing a list: the “following capabilities”. Other phrases are “capability to solve problems”, “capability to use languages”, “capability to communicate”, and “capability to contribute to society”. “Capability” refers to different kinds of capabilities, although they are less varied than for “ability”.

The objects of “acquire” are “broad education”, “high ethical values”, “generosity”, “attitudes to collaborate with others”, “practical attitudes”, and “skills that meet the demands of society”, apart from the abilities and capabilities mentioned above.

3.3. Comparison of Diploma Policies of Women’s and Co-Educational Universities

This subsection compares the DPs of women’s and co-educational universities, based on to Section 3.1 and Section 3.2, using the search engine to explore the co-occurrences of feature words (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of feature words.

Both women’s and co-educational universities highlight “society” in their DPs. Approximately a quarter of all sentences use the word (27.1% and 25.8% for women’s and co-educational universities, respectively). However, while “society” in the co-educational universities DPs appears in references to social contribution (57.6% of co-educational universities), development (20.3%), and responsibility (18.6%), fewer women’s universities refer to these contexts: society and contribution (45.5%), society and develop, and society and responsibility (4.5% each). Women’s universities describe various societies rather than focusing on the leading roles in society of the universities and their students.

The second most frequent word is “ability”; over 81% of women’s universities and 70% of co-educational universities mention it (24.4% of the total sentences in women’s universities’ DPs, 23.9% of those of co-educational universities). Although slightly less frequent, “capability” is also often mentioned in the DPs of both women’s and co-educational universities. As the differences in frequency between “ability to think” and “capability to think” indicate, “ability” can be used flexibly in Japanese to describe specific skills.

Regarding specific abilities, particularly among those often mentioned in the DPs, “ability to think” is frequent in both groups (5.4% for women’s universities, 5.1% for co-educational universities). However, women’s universities refer to the “ability to solve (problems)” (5.9%) more than the “ability to think”. “Ability to judge” appears only four times (1.8% of total sentences) and only three universities (13.6% of all women’s universities) used the word. Contrariwise, “ability to judge” appears 19 times (3.2%), and 16 co-educational universities (27.1%) mention it. A similar tendency is observed slightly more frequently for “ability to express”.

Some of the words are used more by either women’s or co-educational universities. Over half the co-educational institutions (7.1% in frequency) mention “human resources”; less than 20% (1.8% in frequency) of women’s universities mention it. “Human resources” is used to indicate students with specific attributes and skills whom universities aim to foster: “human resources who can contribute to the development of society”, “human resources with international and professional qualities”, and “knowledgeable and educated human resources”.

“Information” is another word that appears more often among co-educational universities, for example, “collect and analyze information”, and “information literacy”. While 17 co-educational universities (28.8%) use “information” (3.7% in frequency), only two women’s universities (9.1%) use the word (0.9% in frequency). Contrariwise, “life” is more often referred to in women’s universities’ DPs (27.3% and 8.5% of women’s and co-educational universities, respectively)—“live an independent life”, “enrich social life”, and “a life based on ‘love, diligence and intelligence’”. Similarly, more women’s universities use “empathy” (27.3%) than co-educational universities do (6.8%), which is confirmed in terms of frequency: “have feelings of empathy for others” and “empathy-oriented humanity”.

Private universities in Japan usually have their “founding spirits” or “principles”, which set the direction of the university’s education in their DPs. “Founding spirit” is used more often in both types of DPs; however, women’s universities are more likely to use it (59.1% of women’s universities, compared to 45.7% of co-educational ones). Only two women’s universities (9.1%) use “founding principles”, while 16 co-educational universities (27.1%) do.

4. Discussion

Both women’s universities and co-educational universities refer to knowledge and abilities in their DPs. They are highly conscious of “society” when describing their students’ attributes. Differences between women’s and co-educational universities are highlighted in references to “society”. Although the educational philosophies of women’s universities include elements of social contribution [23,25], co-educational universities are more aware of their relationships with society, referring to social development by and social responsibility of students [24]. Such attitudes also appear in their frequent references to “human resources”. Co-educational universities seem to emphasize their role to develop the human resources needed by society and business circles. This could be explained by differences in faculty compositions; co-educational universities tend to have wider varieties of departments, which could provide them with more opportunities to apprise themselves of the diverse needs in society. Although women’s universities are expanding their fields of study these days, their roots in empowering female students as described in their founding purpose [1,23,24] may be prioritized in their DPs.

When universities emphasize their relationship with society, co-educational universities seem to view society as something their graduates can create and develop, while women’s universities regard it as given or changing. How their graduates play an active part in society appears to be more important for women’s universities [23,25]. However, these roles are not necessarily to lead and transform society, which could be an indication of gender inequality in the social, economic, and political realms of Japan [28]. Women need to overcome various obstacles to full participation in society before they can engage in transforming and developing society.

In this modern society, the attributes that students should acquire do not depend on gender, and both women’s and co-educational universities DPs include many kinds of abilities. This reflects diversity in outcomes of higher education. However, fewer women’s universities highlight the “ability to judge”. This perhaps suggests an unconscious bias or assumption on their part that women are more suited for general or supportive roles, which reflects the social position of Japanese women (e.g., few women in management positions) [28]. The emphasis on women’s economic independence seen in women’s universities’ DPs may be related to the historical background of vocational education in women’s universities [17] and the traditional views of women’s universities seen in presidents’ messages [23]. The use of “life” by more women’s than co-educational universities also suggests low economic status of women in Japan as well.

Regarding their choice of words, women’s universities seem to prefer soft words [24]. “Principles” in Japanese sounds more logical than “spirits”, which has emotional connotations. The fewer references to “ability to express” by women’s universities may hint at another bias where women are viewed as good at expressing themselves and communicating with others. The greater references to “empathy” by women’s universities may also suggest their expectation that female students have empathy.

Interestingly, the word “leadership” is rarely seen in either group. This may reflect the values that Japanese society places on individuals who can cooperate and collaborate with others rather than those who take the initiative, as seen in “ability to collaborate” and “ability to work with others”.

This study focused on universities in metropolitan areas. Considering the differences in environment between metropolitan and regional universities (e.g., female students are less likely to go on to higher education in rural areas), it is difficult to generalize the results of this study to the whole nation. Thus, it is necessary for future research to expand the target universities to ensure an adequate national-level analysis (e.g., [17,18,19,20]).

The humanities tend to dominate faculty composition in women’s universities, although this has been changing in recent years. This study excluded universities that focus on specific disciplines such as medicine and engineering; however, differences in the fields of study that women’s and co-educational universities offer may have some impact on the results. Future comparisons should ensure similar faculty compositions or involve the same departments for more precise analyses (e.g., [17,18,19,20,21,22]). Also, there are co-educational universities with mostly female or male students, and co-educational universities that used to be women’s universities. These characteristics may influence the disciplines they offer and the graduates’ profiles they aim to foster. It is thus essential for a more in-depth analysis to look more carefully at their backgrounds and student compositions.

The aim of this study was to explore the educational values highlighted in the DPs. Considering that Japanese society is becoming increasingly globalized, multicultural, and diverse, and given the regional disparities in the impact of globalization, future research should focus on how global values and competencies manifest themselves in the DPs and how regional universities’ DPs differ from those of metropolitan universities.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the DPs of women’s universities and compared them to those of co-educational universities to identify educational characteristics of women’s universities in Japan. The results indicate that the DPs of women’s universities highlight their priority of fostering economically independent women, which reflects their founding purpose of empowering women. Women’s universities aim to encourage their graduates to participate actively in society within the current societal context. However, if women’s universities integrate their students’ outcomes into their DPs based on their visions of an ideal society, they could pave the way toward an inclusive and diverse society.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data and search engine are available at https://210.48.237.125/cgi-bin/X.cgi (accessed on 21 October 2023). Since it used private online storage, contact the corresponding author for the user ID and passwords.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Sachio Hirokawa, Kaori Ogashiwa, and Kumiko Kanekawa for their advice developing the analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The list of 81 universities is provided here. Women’s universities are marked with asterisks (*).

| Aikoku Gakuen University * | Aoyama Gakuin University | Asia University |

| Atomi University * | Bunka Gakuen University | Bunkyo University |

| Bunkyo Gakuin University | Chuo University | Chuo Gakuin University |

| Dokkyo University | Edogawa University | Ferris University * |

| Gakushuin University | Hosei University | J.F. Oberlin University |

| Japan Women’s University * | Jissen Women’s University * | Josai University |

| Josai International University | Jumonji University * | Juntendo University |

| Kamakura Women’s University * | Kanagawa University | Kanto Gakuin University |

| Kawamura Gakuen Women’s University * | Keiai University | Keisen University * |

| Kokugakuin University | Kokushikan University | Komawaza University |

| Komazawa Women’s University * | Kyoritsu Women’s University * | Meiji University |

| Meiji Gakuin University | Meikai University | Meisei University |

| Mejiro University | Musashi University | Nihon University |

| Nishogakusha University | Otsuma Women’s University * | Reitaku University |

| Rikkyo University | Rissho University | Sagami Women’s University * |

| Seigakuin University | Seijo University | Seikei University |

| Seisen University * | Seitoku University * | Senshu University |

| Showa Women’s University * | Shukutoku University | Shumei University |

| Soka University | Surugadai University | Taisho University |

| Takushoku University | Tamagawa University | Teikyo University |

| Teikyo Heisei University | Tokai University | Tokyo City University |

| Tokyo Future University | Tokyo International University | Tokyo Kasei University* |

| Tokyo Kasei Gakuin University * | Tokyo Keizai University | Tokyo Junshin University |

| Tokyo Seitoku University | Tokyo University of Science | Tokyo University of Social Welfare |

| Tokyo University of Technology | Tokyo Women’s Christian University * | Toyo Eiwa University * |

| Tsuda University * | Tsurumi University | University of the Sacred Heart, Tokyo * |

| Urawa University | Wako University | Waseda University |

References

- Aoki, T. Contemporary significance of women’s colleges. In Discussions on Women’s Universities, Japan Women’s University Research Institute for Women’s Education; Domesu Publisher, Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 1995; pp. 10–25. [Google Scholar]

- Serious Decline in Women’s Universities: 69% of Private Universities Were Below Capacity in the Last Financial Year. Available online: https://www.yomiuri.co.jp/kyoiku/kyoiku/news/20230620-OYT1T50229/ (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Background to the “Prestigious” Keisen Jogakuen University’s Suspension of Recruitment the Number of Female Students at Waseda-Keio MARCH is Increasing Year by Year. Available online: https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/664007 (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Women’s Universities, Seeking a Way Forward. Available online: https://digital.asahi.com/articles/ASR7R5FJ6R6FUTIL049.html (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Knowledge Station. Available online: https://www.gakkou.net/ (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Nakajima, K. Phases of women’s higher education in modern Japan. In Women’s Higher Education; Japan Women’s University Research Institute for Women’s Education; Gyosei: Tokyo, Japan, 1987; pp. 24–50. [Google Scholar]

- History of Women’s Higher Education in Japan. Available online: https://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/kyodo-sankaku/ja/activities/model-program/library/UTW_History/Page05.html (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Ando, Y. 70 Years’ progress of women’s universities and colleges in Japan: Focusing on institutional changes. Mukogawa Women’s Univ. Inst. Educ. 2017, 47, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mahashi, M. Current situation and challenges of Japanese women’s universities. In Discussions on Women’s Universities; Japan Women’s University Research Institute for Women’s Education; Domesu Publisher, Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 1995; pp. 144–172. [Google Scholar]

- Trend in Number and Percentage of Universities, Women’s Colleges and Junior Colleges. Available online: http://kyoken.mukogawa-u.ac.jp/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/21_12_03.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- First Stage Proposal of Japanese Council for the Creation of Future Education. Available online: https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/kyouikumirai/pdf/220510gaiyou.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Women’s Universities in Rural Areas Going to Co-Educational. Available online: https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGKKZO72045020Q3A620C2TCN000/ (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Basic School Survey. Available online: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&toukei=00400001&tstat=000001011528 (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Omori, F. Pitfalls of Japanese undergraduate education. In Global Studies of Undergraduate Education: Exploring the Shift to International Perspectives; Yonezawa, A., Shimauchi, S., Yoshida, A., Eds.; Akashi Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 2022; pp. 193–215. [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the Formulation and Implementation of the Diploma Policy, Curriculum Policy and Admission. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chukyo/chukyo4/houkoku/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2016/04/01/1369248_01_1.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- UK Quality Code for Higher Education. Available online: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/13488/3/Quality-Code-Chapter-A3.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Kurihara, I. The analysis of liberal arts by specialized education in a university in Japan: A focus on discipline and diploma policy in the faculties of arts and sciences. Dep. Bull. Pap. Dep. Univ. Manag. Policy Stud. Univ. Tokyo 2018, 8, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, S. The position of “sustainable tourism” in the diploma policy of tourism universities: A text analysis. Dep. Bull. Pap. Hannan Univ. 2021, 56, 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Kubota, Y.; Ikeda, F. Learning outcomes of social work professional training programs from the perspective of the diploma policy. J. Compr. Welf. Sci. 2023, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagama, E.; Yoshimura, S. The difference of liberal arts education in nursing universities from the consideration of diploma policies and curriculum of liberal arts. J. Jpn. Acad. Nurs. Ed. 2023, 32, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, K. KH Coder 3 Reference Manual. Ritsumeikan University. 2016. Available online: http://khcoder.net/en/manual_en_v3.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Ogashiwa, K.; Sugihara, T.; Kanekawa, K.; Kitanaka, Y.; Noguchi, K.; Aihara, S.; Mori, M.; Hirokawa, S. Quality assurance in education through the diploma policy and president’s message-an analysis focused on local community. In Proceedings of the 2018 7th International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics (IIAI-AAI), Yonago, Japan, 8–13 July 2018; pp. 964–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, Y. References to gender in the homepage of women’s university presidents. Bull. Inst. Interdiscip. Stud. Cult. Doshisha Women’s Coll. Lib. Arts 2005, 22, 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Okada, N. A typological study of fundamental philosophies of private universities: The positions of women’s universities. Bull. Grad. Sch. Educ. Hiroshima Univ. 2003, 51, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Fukaya, K. Feature comparison of women’s colleges using text mining in the U.S. and Japan. J. Sch. Educ. 2018, 11, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, Y. Research on women’s colleges in the United States: An overview of literatures since 1970s. Dep. Bull. Pap. Grad. Sch. Educ. Univ. Tokyo 2015, 54, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaiser, S.; Ali, R. Text mining: Use of TF-IDF to examine the relevance of words to documents. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2018, 181, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Falls Nine Positions to 125th in WEF Gender Gap Report. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/06/21/national/japan-gender-gap-ranking-lower-2023/ (accessed on 22 July 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).