Religious Doubts and the Problem with Religious Pressures for Christian Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Self-Determination Theory and the Concept of “Controllers”

Religious Pressures as Possible Controllers

3. Religious Doubt and Religious Exploration

3.1. Religious Exploration as Normative

3.2. Religious Exploration and the Continuum of Internalization

4. The Potential Utility of Religious Doubt

Homeostatic Forces Preventing Religious Doubt

5. The Possible Relationship of Religious Doubt with Religious Pressures

6. Aim of Study

7. Materials and Methods

8. Procedures and Recruitment

9. Participants

10. Instruments

10.1. Religious Doubts Questionnaire

10.2. Religious Pressures Questionnaire

10.3. Spiritual/Religious Relatedness and Self-Mastery Scale

11. Analytical Strategy

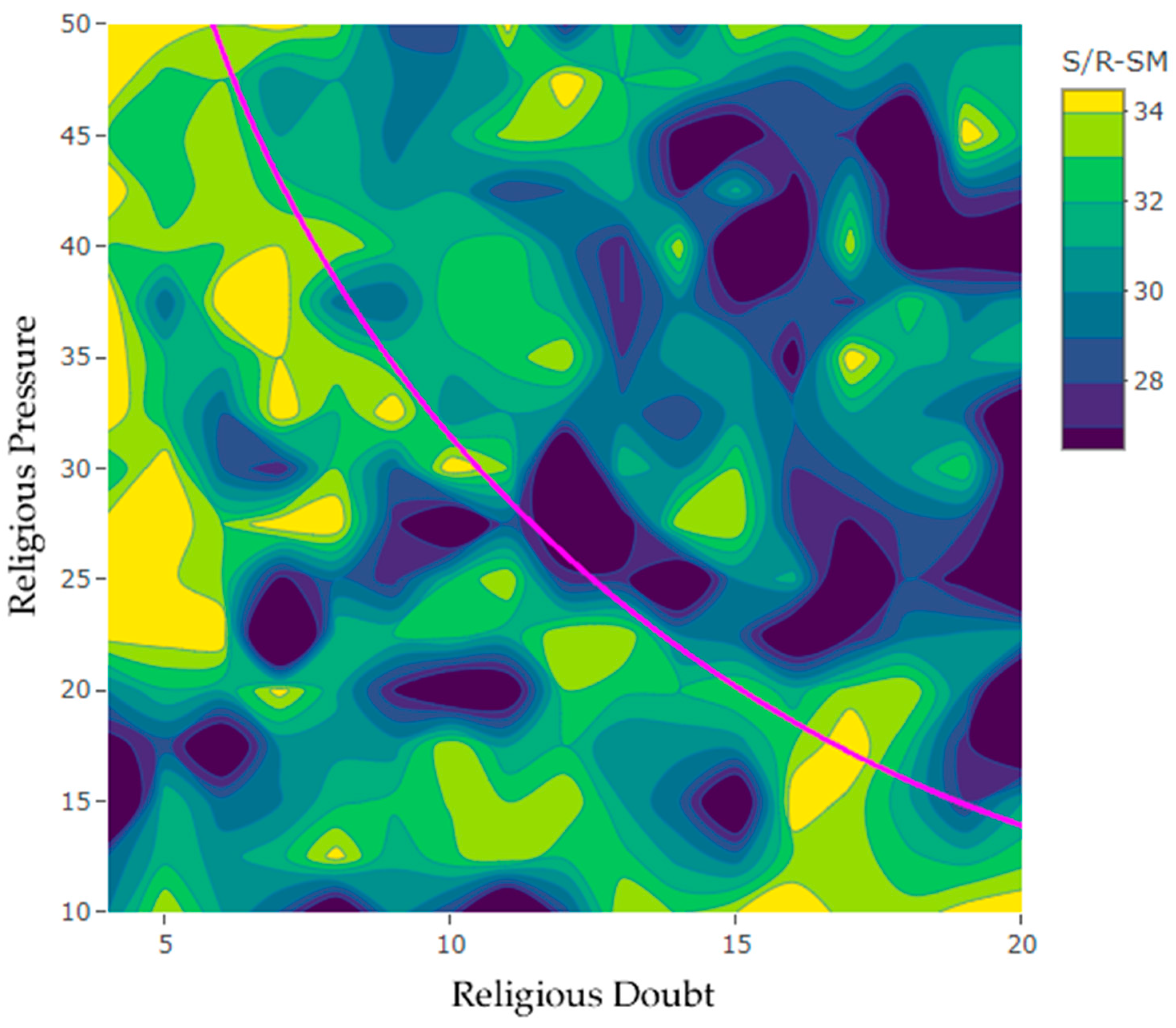

12. Results

13. Discussion

I feel that at (the educational environment) there is a very high expectation for perfection and not a lot of room for error. It creates immense pressure that condemns me into believing certain things as opposed to exploring what I believe and why (22-year-old female).

For being all-powerful, it seems like a shitty thing for God to have let her die meaninglessly when she was so devoted to helping others and taking care of her son who needed her desperately. There was no reason for God to let that happen … no purpose whatsoever (20-year-old male).

(Educational environment) is not a very safe place for asking questions about issues that we as Christians really need answers for and don’t have. I am (not) comfortable asking questions in general out of fear of feeling stupid or ashamed.

I had already suffered a debilitating amount of doubt over the years, including during the time (friend) and I were roommates. Before his death, I had already gotten to the place where I considered myself an atheist/agnostic. Yet surprisingly, his death caused me to … be open to the existence of God, as (his) death was so shocking and untimely that a part of me wondered if there was more to his death than I could see (22-year-old male).

Through this loss I have actually felt the greater power of God, because I got to see and reflect on how He was there in my grandmother’s life and how He interacted with her life, before I was even around. I felt more closely connected to God, my grandmother and to the gravity of time (22-year-old female).

14. Religious Pressures as Both Internal and External “Controllers” of Religious Doubt

15. Limitations and Implications for Research

16. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walker, A.C.; Lang, A.S.I.D. Perceived religious pressures as an antecedent to self-reported religious development and wellbeing. J. Psychol. Theol. 2022, 51, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assor, A.; Cohan-Malayev, M.; Kaplan, A.; Friedman, D. Choosing to stay religious in a modern world: Socialization and exploration processes leading to an integrated internalization of religion among Israeli Jewish youth. Motiv. Relig. 2005, 14, 105–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, M.; Assor, A.; Manzi, C.; Regalia, C. Autonomous versus controlled religiosity: Family and group antecedents. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 2015, 25, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Eghari, H.; Patrick, B.C.; Leone, D. Facilitating internalization: The Self-Determination Theory perspective. J. Personal. 1994, 62, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joussemet, M.; Landry, R.; Koestner, R. A Self-Determination Theory perspective on parenting. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research; Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.M., Eds.; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Trouilloud, D.; Sarrazin, P.; Bressoux, P.; Bois, J. Relation between teachers’ early expectations and students’ later perceived competence in physical education classes: Autonomy supportive environment as moderator. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Simons, J.; Lens, W.; Sheldon, K.M.; Deci, E.L. Motivating learning, performing, and persistence: The synergistic effects of intrinsic goal contents and autonomy supportive contexts. Personal. Process. Individ. Differ. 2004, 87, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.C.; Hathcoat, J.D.; Munoz, R.; Ferguson, C.; Dean, T. Self-Determination Theory and perceptions of spiritual growth. Christ. High. Educ. 2021, 20, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.C.; Rhoades, M.G. Religious schemas through the lens of Self-Determination Theory. Christ. High. Educ. 2021, 21, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemeyer, B. Enemies of Freedom: Understanding Right-Wing Authoritarianism; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hathcoat, J.D.; Fuqua, D.R. Initial development and validation of the Basic Psychological Needs Questionnaire–Religiosity/Spirituality. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2014, 6, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.R. Doubt. In Baker Encyclopedia of Psychology; Benner, D.G., Ed.; Baker Book House: Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 1990; pp. 327–329. [Google Scholar]

- Puffer, K.A.; Pence, K.G.; Graverson, M.; Wolfe, M.; Pate, E.; Clegg, S. Religious doubt and identity formation: Salient predictors of adolescent religious doubt. J. Psychol. Theol. 2008, 36, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ano, G.G.; Vasconcelles, E.B. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 61, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, B.D.; Gramling, S.E. Patterns of religious coping among bereaved college students. J. Relig. Health 2014, 53, 157177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, M.G.; Walker, A.C. Spiritual struggle and spiritual growth of bereft college students at a Christian evangelical university. Spiritus 2021, 6, 309–332. Available online: https://digitalshowcase.oru.edu/spiritus/vol6/iss2/10/ (accessed on 22 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Fowler, J.W. Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning; Harper Collins Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Buker, B. Expanding God’s redemptive fractal. Salubritas 2021, 1, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J.; Jensen, L.A. A congregation of one: Individualized religious beliefs among emerging adults. J. Adolesc. Res. 2002, 17, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C.M.; Nelson, L.; Urry, S. Religiosity and spirituality during the transition to adulthood. Int. J. Behavioral. Dev. 2010, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.L. Religious ego identity and its relationship to faith maturity. J. Psychol. 1998, 132, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcia, J.E. Development and validation of ego-identity status. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1966, 3, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Goodwin, E.B.; Michael, C.W. Subjective well-being and religious ego identity development in conservative Christian university students. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. Christ. High. Educ. 2021, 11, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, T.S. Proposed levels of Christian spiritual maturity. J. Psychol. Theol. 2004, 32, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streib, H.; Hood, R.W.; Klein, C. The religious schema scale: Construction and initial validation of a quantitative measure for religious styles. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 2010, 20, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, B.; Streib, H. Faith development, religious styles, and biographical narratives: Methodological perspectives. J. Empir. Theol. 2013, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, J.J.; Pargament, K.I.; Grubbs, J.B.; Yali, A.M. Religious and spiritual struggles scale: Development and initial validation. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2014, 6, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Roberts, L.B.; Gibbons, J.A. When religion makes grief worse: Negative religious coping as associated with maladaptive emotional responding patterns. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2013, 16, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K.I.; Smith, B.W.; Koenig, H.G.; Perez, L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1998, 37, 710–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K.I.; Koenig, H.G.; Tarakeshwar, N.; Hahn, J. Religious coping methods as predictors of psychological, physical, and spiritual outcomes among medically ill elderly patients: A two-year longitudinal study. J. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K.I.; Falb, M.D.; Ano, G.G.; Wachholtz, A.B. The religious dimension of coping: Advances in theory, research, and practice. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2nd ed.; Paloutzian, R.F., Park, C.L., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 560–579. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke, C.J.; Glenwick, D.S.; Cecero, J.J.; Kim, S. The relationship of religious coping and spirituality to adjustment and psychological distress in urban early adolescents. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2009, 12, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Time of change? The spiritual challenges of bereavement and loss. OMEGA 2006, 53, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillevoll, K.; Kroger, J.; Martinussen, M. Identity status and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Identity Int. J. Theory Res. 2013, 13, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.C.; Gewecke, R.; Cupit, I.N.; Fox, J.T. Understanding bereavement in a Christian university: A qualitative exploration. J. Coll. Couns. 2014, 17, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepper, M.R.; Greene, D. Turning play into work: Effects of adult surveillance and extrinsic rewards on children’s intrinsic motivation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1975, 31, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, J.D.; Smith, H.L. The influence of organizational structure on intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.C.; Hathcoat, J.D. Discrepancies between student and institutional religious worldviews. J. Coll. Character 2015, 16, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.C.; Lang, A.S.I.D. Dataset: The Problem with Pressures for Christians (Figshare) [Dataset]. Available online: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Dataset_The_Problem_with_Pressures_for_Christians/20452560 (accessed on 22 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. In R Foundation for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Therneau, T.; Atkinson, B.; Ripley, B. Rpart: Recursive Partitioning and Regression Trees; Version 4.1.16. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rpart (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Astin, A.W.; Astin, H.S.; Lindholm, J.A. Assessing students’ spiritual and religious qualities. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2011, 52, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, R.L. Understanding the spiritual development and the faith experience of college and university students on Christian campuses. J. Res. Christ. Educ. 1999, 8, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.G.; Talbot, T.M. Defining spiritual development: A missing consideration for student affairs. Naspa J. 1999, 37, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual/Religious Relatedness | 33.97 (5.712) | |||

| Spiritual/Religious Self-Mastery | 0.534 *** | 30.44 (4.776) | ||

| Religious Doubts | −0.279 *** | −0.267 *** | 9.90 (4.280) | |

| Religious Pressures | 0.347 *** | 0.164 *** | −0.232 *** | 37.52 (9.327) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Walker, A.C.; Lang, A.S.I.D.; Munoz, R. Religious Doubts and the Problem with Religious Pressures for Christian Students. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 975. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13100975

Walker AC, Lang ASID, Munoz R. Religious Doubts and the Problem with Religious Pressures for Christian Students. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(10):975. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13100975

Chicago/Turabian StyleWalker, Andrea C., Andrew S. I. D. Lang, and Ricky Munoz. 2023. "Religious Doubts and the Problem with Religious Pressures for Christian Students" Education Sciences 13, no. 10: 975. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13100975

APA StyleWalker, A. C., Lang, A. S. I. D., & Munoz, R. (2023). Religious Doubts and the Problem with Religious Pressures for Christian Students. Education Sciences, 13(10), 975. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13100975