Abstract

Online assessment of foreign-language learners, particularly of their oral skills, is a challenge for both students and teachers. Assessing language skills face to face, during a conversation between the examiner and the candidate, facilitates natural communication and is likely to provide a more accurate assessment of the student’s language proficiency level. A change in the scenario and the use of digital tools can intimidate students and take away the naturalness and warmth of the interview. The purpose of this paper is to examine the suitability of Blackboard Collaborate as a learning management system for assessing English speaking skill and other factors that influence students’ online performance. A total of 180 students from 7 different undergraduate programs in the fields of technology, environmental sciences and health sciences were assessed according to the structure of a standardized test. Using a mixed-methods approach, their results were contrasted with responses to a final survey to examine the positive or negative impact of online testing on students’ attitudes, performance and achievement. The Blackboard digital platform proves to be a suitable and convenient online framework for optimal speaking performance, and the examiner’s attitude is also a determining factor in students’ success.

1. Introduction

The achievement of learning goals in foreign language learning must be checked by means of consistent assessment types and reliable tools which reveal the students’ actual level of linguistic competences. Apart from the numerous methods of standardized testing which are currently widely applied to certify individuals’ proficiency level in a language, new forms of formative assessment have been designed in higher education to check students’ language learning. Standardized tests in online formats have proved to be a suitable and profitable way to provide a great number of students with access to certified exams as well as a means of facilitating and shortening grading time. Both easy access and time-saving procedures, together with proven validity, are nowadays among the most valued features in standardized testing [1]. Focusing on English as a foreign language (EFL) in higher education (HE), English learning in Spain is usually incorporated into the curriculum in undergraduate programs as English for specific purposes (ESP). Irrespective of the specific field of study in which English is taught, foreign language (FL) learning tends to take place in a highly contextualized and personalized environment. Learning goals are not restricted to linguistic skills; they also include a carefully selected range of sociolinguistic competencies to be developed throughout the learning period. Students’ practice of the language with a communicative purpose, guided by the instructor, turns out to be a valuable source of information and feedback for both the instructor and students. Foreign language learning in this context is a natural process where interpersonal communication is an important part and where not only linguistic skills are developed but also other non-linguistic skills, including intercultural competence in a professional setting [2]. These university scenarios, where ESP is taught face to face, make it easier for professors to assess students. In turn, students find a safe environment in which to be assessed.

2. Literature Review

As far as speaking skills are concerned, oral assessment and role-play situations have often been used by instructors to assess students’ oral expression in EFL. The role-play technique allows students to develop their creativity in order to perform their roles. It also challenges their thinking and motivates them to integrate and use their social skills. In some ESP courses, instructors have used face-to-face role-play as a suitable way to develop students’ skills of initiative, communication, problem solving, self-awareness and cooperative work in teams. Additionally, face-to-face role-playing prepares students for communication in real-life situations [3].

The growth of universities and spread of students into different campuses posed a challenge for higher education programs. Many universities were forced by the COVID-19 pandemic to transform most—if not all—their programs into an online modality. This has meant not only a great investment of resources and effort but also the launching of online courses supported by different learning management systems (LMSs). In the case of foreign languages, whose theoretical content is scarce compared to practical content, this transformation has posed a greater challenge. LMSs offer many utilities for the presentation of contents and, very often, they include technical features to let students practice the language both orally and in written form [4]. These LMSs can connect participants live on a video conference [5,6]. The video conference strategy involves audiovisual interaction, which maintains key elements of the communication process in the target language [7]. But online platforms lack the closeness and warmth of personal face-to-face communication [8]. The lack of “presence” is a factor that can lead to dissatisfaction with learning management systems. Some studies indicate that EFL students consider the full online digital learning experience they had during the emergency remote teaching (ERT) period to be less preferable to face-to-face learning [9].

Other studies show a high level of concern among university students about the decrease in communicative interaction with the teacher [10]. These findings are similar to those of other studies that note the “marginalization” or exclusion of the human factor from educational practices in the context of digitalization [11]. This exclusion results in negative trends such as dehumanization, formalization of the educational process and reduced effectiveness in the development of communication skills [12].

As regards skills and competencies involved in FL learning, educational researchers recognize the difficulty in assessing them in online environments, especially the oral ones [13,14]. Extensive research has analyzed the use of technology in the assessment of EFL oral skills, a field which also evolves at a fast pace due to the continuous development of new software which can be used for this purpose [15,16,17]. The use of students’ video or audio recordings to assess their speaking skill has gained popularity in some undergraduate FL courses [18,19]. Some studies have even examined non-native speakers’ evaluations of their own speech [20], and some results reveal that these evaluative tasks contribute to developing the students’ phonological consciousness and their autonomy and motivation to keep learning [21]. By contrast, some authors report a good number of institutions’ preference for blended learning practices, combining the use of an LMS for learning with face-to-face practices for skill assessment [22]. When teaching and assessing speaking, it is important to consider the two main features of the language: accuracy (precision and linguistic acceptability of the language) and fluency (ability to develop ideas and ways of expressing them). There are some linguistic components, such as pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar, where accuracy must be tested. Oher components, such as mechanical skills, language use and judgement skills, require the examiner to test the students’ ability to use the language to communicate effectively and fluently [23].

Determining the level of speaking proficiency in a foreign language includes not only language ability but also strategic, sociolinguistic and pragmatic competencies, which can only be assessed by a personal examiner using a holistic approach [24]. Studies have revealed the importance of teacher involvement in assessment activity to ensure students feel uninhibited and motivated to expand their oral contributions [25]. Using teachers as examiners is a well-functioning procedure in terms of assessment for learning but raises doubts regarding the assessment of learning and standardization, as some researchers suggest [26].

3. Objectives

The main objectives of this study are the following:

- To check whether Blackboard is a reliable LMS for the assessment of the oral competence of ESP students (English for specific purposes).

- To check whether Blackboard is technically efficient for assessing speaking.

- To find out what other factors—apart from the efficiency of the platform—can influence students’ speaking performance.

- To find out how students perceive the potential advantages of using Blackboard compared to face-to-face speaking assessment.

4. Context and Test Group

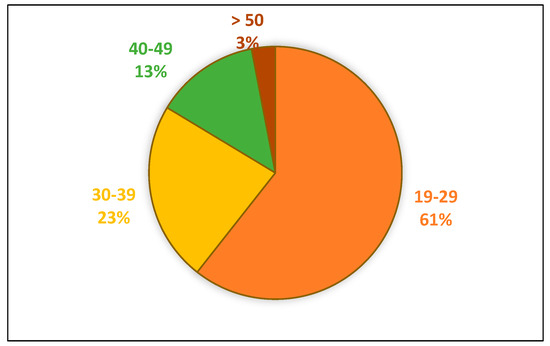

ESP is a compulsory six-credit course. It is taken by all university students during one semester at UCAV (Catholic University Saint Teresa of Avila, Castile and Leon, Spain). An intermediate level of English (B1-B1+) (according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, CEFR) is to be achieved in each of the undergraduate programs. The language taught is academic English with specific language depending on students’ fields of study. Participants in the present research were 180 undergraduate students taking English as a foreign language (EFL) in Forestry, Agricultural and Mechanical Engineering (29%), Environmental Sciences (7.3%), Psychology (9.7%), Nutrition (17%) and Nursing (37%) in the academic year 2020–2021. The test group consisted of 165 students who completed the final survey: 67 men (40.6%) and 98 women (59.4%). Figure 1 shows the age composition of the test group.

Figure 1.

Test group age range.

A total number of 180 students took a speaking test at the end of the spring and fall semesters in the academic year 2020–2021, as part of their FL final exam, via an online platform. ESP courses were delivered online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, using Blackboard as a learning management system (LMS). The specific version supporting instruction was Blackboard Learn 3800 (Blackboard Collaborate Ultra), which offers a wide range of functionalities for FL teaching and learning and, in particular, for the practice and assessment of oral competence. Blackboard Learn 3800 was chosen because it is the LMS used at the Catholic University Saint Teresa of Avila. Following the distinction that some researchers make within the oral competence category [27], we will specifically focus on the speaking sub-competence of foreign language learning, henceforth referred to as speaking skill.

5. Methodology

A mixed-methods research approach was adopted [28], and quantitative and qualitative data were collected. Qualitative data were provided by the examiner’s observations, as recorded during the speaking tests, and student responses to open-ended questions included in an anonymous online questionnaire. Quantitative data were provided by a web-based survey of closed-ended questions and speaking test results corresponding to four academic years.

Procedure

Speaking tests for 180 undergraduate students took place in ten different online sessions. They were performed individually, in the format of a structured interview between the candidate and the examiner, who acted as the instructor in all sessions. The students, in turn, entered the virtual classroom on the Blackboard platform and the examiner asked the candidate three questions of three different types: (a) open-ended questions referring to personal background or experience; (b) prompts for the candidate to speak on a topic for two minutes; and (c) opinion questions about more general topics. Each performance was recorded, and the length was between six to eight minutes on average. Rubrics were used for the assessment of a variety of features which are indicators of oral proficiency [27]: lexical (vocabulary suitability for the topic and context), morphosyntactic (language usage and discourse structures), phonological (pronunciation and intonation), sociolinguistic (adequacy for the context and register and fluency). The rubrics have been validated and are used at IELTS (International English Language Testing System) speaking exams, where band scores range from 0 to 9. Students were given the assessment criteria before speaking tests were performed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Speaking exam criteria.

After all speaking tests were completed, students were invited to answer an online survey delivered through Google Forms (Appendix A). The survey was answered anonymously and consisted of 16 items: 3 questions on personal information (degree, sex and age), 11 multiple-choice questions and 2 open-ended questions included in items 7 and 14 in the questionnaire. The content validity of the survey was assessed by two experts, both professors of English at the university. As a result, one of the items was discarded before the survey was administered.

Out of 180 students, 165 answered the online survey, which represents a high response rate (91.6%).

6. Results

Students’ responses in the survey reveal that for 62 students (37.6%), it was the first time they had taken a speaking test in an FL. For the other 103 students (62.4%), it was not.

However, 152 students (92.1%) had never taken a speaking test via an online platform, compared to only 13 (7.9%) who had done so previously. The examiner’s reported observations on Blackboard technical features are summarized in Table 2. They shed light on how they may have had a positive or negative impact on the students’ speaking test.

Table 2.

Observations on Bb technical features during speaking tests.

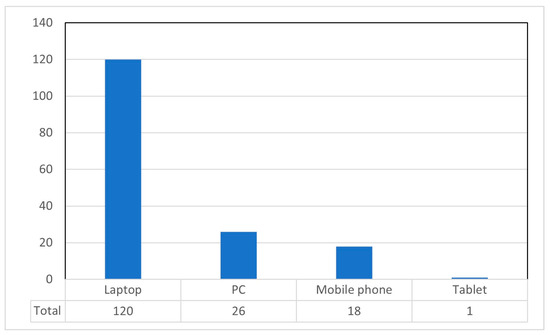

The few incidents (a total of 12), which all occurred when candidates entered the virtual classroom, were sorted out by changing the student’s device or moving to another location where the internet coverage was better or broadband was available. In these particular cases, access to the Blackboard platform from a mobile phone rarely failed. Figure 2 shows the range of devices used by students to access the virtual classroom for the speaking test. As can be observed, most students (72.7%) used a laptop for the online speaking test. Tablets were the device with the lowest usage rate.

Figure 2.

Digital devices used for speaking test.

As described above, each of the 165 students was asked three different questions in the course of a semi-structured interview. They were presented with a progressive level of difficulty and aimed to assess the student according to the rubrics. They ranged from simpler questions referring to the candidate’s personal background, preferences and experience, which build up the person’s self-confidence [29], to more complex questions asking them to express their opinion on general issues. Each of the indicators of oral proficiency was scored from 0 to 5, and the total overall score was calculated and provided on a scale up to 10. The target band score, according to IELTS speaking exams, is 5, corresponding to a B1+ English level in the CEFR. Speaking test results for 2020–2021 are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Online speaking test results, 2020–2021.

Though mean scores varied depending on the program, figures show high levels of performance. Standard deviation values were low except for Nursing students. Only 26 out of 180 students did not achieve the minimal level of speaking competency required for an intermediate level of oral proficiency in English. This represents only 14.4%, in contrast with 85.6%, the percentage of successful students.

Scores from face-to-face speaking tests taken previously by another 80 undergraduate students in Engineering and Environmental Sciences, Psychology and Nursing in the academic years 2017–2018, 2018–2019 and 2019–2020 are shown in Table 4. Nursing students’ scores for the academic year 2019–2020 are not included in Table 4, because the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring semester of 2020 forced Nursing students to be assessed online. Scores from face-to-face speaking tests in Nutrition are not included either, because this is an online program and tests are exclusively taken online. The structure of the face-to-face speaking test, the assessment criteria and the scoring scale were the same as for the online speaking tests. The target level for the English language was also the same.

Table 4.

Face-to-face speaking test results (academic years 2017–2020).

The results of the face-to-face speaking test for students of Forestry Engineering, Agricultural Engineering, Mechanical Engineering and Environmental Sciences are considered together because they were grouped in the same class when they took English as a foreign language. The results of the online speaking tests and face to face speaking tests are contrasted in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of speaking tests in both modalities.

Overall, except for Nursing and Psychology students, mean scores were higher when speaking tests were taken online.

When the test group was questioned about which modality was preferred for taking a speaking test (either online or face to face), 65 respondents (39.4%) preferred the face to face mode and 100 (60.6%) expressed their preference for the online mode. Table 6 summarizes the reasons for students’ test modality preferences.

Table 6.

Reasons for students’ test-mode preferences.

The three major reasons alleged by candidates who preferred face-to-face speaking test to online testing were of a personal and technical nature. On the one hand, closeness, personal interaction, naturality and the possibility of having communication supported by gestures and body language face to face offer students more confidence to express themselves in a humane environment. On the other hand, the absence of interruption risks due to technical failures lowers anxiety associated with oral communication in a foreign language.

By contrast, those reasons for a face-to-face testing preference were overshadowed by convenience, comfort and time efficiency offered by online speaking testing. The only more personal reason adduced for an online testing preference is the fact that taking the test at home or in a familiar environment is a source of comfort and relaxation, which favors fluent oral communication.

Regarding the examiner’s non-verbal feedback and attitude during the online speaking test, 143 students (87.2%) stated that her friendly and supportive attitude helped them in their speaking performance. For 19 students (11.6%), the examiner had a neutral attitude, and only 2 (1.2%) had the perception that the examiner was too serious and strict. The second open-ended question in the survey was “In general terms, do you think that Blackboard virtual classroom is a suitable means to take a speaking test? Why?” Overall, 147 students (89%) responded affirmatively and 18 (11%) negatively. Students’ responses reveal that they do consider Blackboard Collaborate Ultra (Bb) a suitable LMS for taking oral exams because of the following reasons:

- Optimal audio and video quality;

- Easy to use and intuitive;

- Simple to connect to and access;

- Quick;

- Safe during exams: uninterrupted audiovisual communication;

- Convenient and time-saving;

- Agile and dynamic, with useful features.

7. Discussion

Discussion of the results is in line with the research objectives. In relation to Objective 1, “To check whether Blackboard is a reliable LMS for the assessment of the oral competence of ESP students (English for Specific Purposes)”, audiovisual intercommunication with no interruptions makes it possible to have continuous interpersonal communication. Likewise, it enables the synchronic completion of different tasks to assess the candidate’s speaking proficiency at lexical, grammatical, phonological, discourse and sociolinguistic levels. As other researchers have also pointed out [30], the possibility of recording the session on the platform lets the examiner replay the video of students’ speaking performances to focus on students’ utterances and speech details. This recording feature facilitates a more accurate assessment of a student’s speaking skill.

Regarding Objective 2, “To check whether Blackboard is technically efficient for assessing speaking”, synchronic image and sound with no streaming delays optimized interpersonal communication during the exam. A total of 60.6% of students expressed their preference for taking their speaking exam via the Bb platform, and 89% recognized its optimal performance during the exam as well as its easy and convenient use and access. This latter statement is interesting to consider since—as demonstrated by the students’ age range—not all of them may have a high level of digital literacy, which is a prerequisite for mastering a digital platform and feeling confident with using it [31]. Overall, 61.8% of students were satisfied with their own performance in the speaking test and 38.2% were not. Of those who were not satisfied, only 3.1% attributed their poor performance to device failure or poor internet connection. Finally, the platform’s versatility allows access from any digital device, making it more convenient to use.

As far as Objective 3 is concerned, “To find out what other factors—apart from the efficiency of the platform—can influence the students’ speaking performance”, answers to open-ended question 1 in the survey (i.e., “Which modality do you prefer to take a speaking exam: face to face or online and why?”) reveal at least three factors. Firstly, speaking to the examiner through a camera provides a “safety barrier” that makes students feel less tense, nervous or embarrassed. A total of 47% of students who prefer online speaking tests mentioned this favorable factor. Secondly, 9% of students who shared the same online preference cited the fact that they were in a familiar place or at home as a contributing factor to relaxation and greater fluency when speaking in the FL. Thirdly, and most importantly, 87.2% of all 165 respondents recognized the examiner’s friendly and supportive attitude as a crucial and beneficial factor in reducing psychological barriers to speak more confidently in the foreign language. As was stated by one of students in the survey, “closeness between student and examiner depends not so much on the digital platform but on the examiner’s attitude”. This is in line with research which suggests that some of the problems experienced in online testing may be personal, for example, anxiety about using technology and being out of one’s comfort zone [32].

Finally, with regard to Objective 4, “To find out how students perceive the potential advantages of using Blackboard compared to face-to-face speaking assessment”, the alleged reasons for students’ preference for online testing are—in order of priority—the following ones. (a) Convenience and practicality and (b) talking through the screen facilitates higher concentration on tasks and reduces nervousness. This is consistent with studies which show students’ preference for online speaking assessment, especially in the aspect of decreasing the stress associated with speaking in public [9]. (c) It makes candidates feel more self-confident and less embarrassed. (d) It lets students save a great amount of time since they need not travel or miss other academic or professional activities. (e) The possibility of being examined from home or a familiar environment relieves the situational tension associated with an oral examination. Overall, the online platform Blackboard Collaborate Ultra proves to be a suitable LMS for optimal speaking performance and assessment, and the attitude of the examiner is also a conditioning factor in the achievement of oral proficiency by the students. Considering that for 92.1% of the students, this was the first time they had taken a speaking test on an online platform, the responses to the survey show a high level of satisfaction with the experience as well as with their oral exam results. Speaking tests taken by undergraduate students via the Blackboard Collaborate virtual classroom had slightly better results than those corresponding to face-to-face speaking tests taken by students in previous years, with the only exception of Nursing and Psychology students. According to some studies, it should be considered that even though there is a general tendency towards acceptance of virtual learning and assessment in relation to oral skills, there is a general preference of university students and instructors for face-to-face assessment environments whenever conditions make it possible [33,34]. Face-to-face oral communication is facilitated by proximity, personal interaction, naturalness and non-verbal communication.

8. Conclusions

Although the test group was relatively small, the range of undergraduate academic profiles tested using Blackboard was sufficient to support the following conclusions.

The present study proved that the Blackboard Collaborate platform is a reliable LMS for the assessment of the oral competence of ESP (English for specific purposes) students. Its audiovisual tools allow the synchronous completion of different tasks to assess the candidate’s speaking skill at the lexical, grammatical, phonological, discourse and sociolinguistic levels.

It can be concluded that it provides a secure online environment for an oral examination, both from the examiner’s observation and the students’ responses.

From a technical point of view, this study verified that Blackboard is efficient for the assessment of speaking, as synchronous image and sound with no streaming delay optimizes interpersonal oral communication during an exam. From the students’ point of view, it is significant that 89% of the students in the test group considered Blackboard to be a suitable platform for the assessment of speaking skills. It can be concluded that speaking assessment via Blackboard can have a positive washback effect on students [35]. As some authors point out, it is a mistake to assume that e-learning assessment is of lower quality than face to face assessment [36].

Other factors identified in this study to have an impact on students’ online speaking performance are more psychological in nature. Provided the candidate’s internet connection is robust enough to allow uninterrupted streaming, talking to the examiner through a camera makes students feel more confident and results in less tension, nervousness and embarrassment. The option of being tested at home or in a familiar environment was also proved to be a powerful source of comfort and relaxation for candidates. Finally, the friendly and supportive attitude of the examiner also proved to be a beneficial factor in reducing psychological barriers and promoting more confident and fluent speaking in the foreign language.

Leaving aside other factors related to candidates’ personal backgrounds and experiences that might influence their different opinions on the possible advantages or disadvantages of taking a speaking test online versus face to face, the survey results show that almost two thirds of the test group preferred the online mode. Some of the most prominent reasons given by students for preferring online assessment are convenience, saving time, ease of concentrating on the task, relaxation and comfort. Comparing the results of speaking tests in both modes, those corresponding to tests taken via the Blackboard platform were slightly higher in four out of the six undergraduate programs studied. This tendency shows that student satisfaction with speaking tests via this LMS is usually in line with assessment results. However, the number of test groups taking online language tests needs to be increased, as well as the variety of programs, in order to obtain more conclusive results.

This successful online testing experience was a source of confidence and self-motivation for both teachers and students, not only for oral communication in the target language but also for the development of technical and software skills that can lead to further successful online language assessment. In the same way, teachers can find on online platforms such as Blackboard a suitable learning management system for the assessment of oral language skill in a more efficient way and in the best technical conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I.M.-A.; methodology, M.N.B.-E. and A.I.M.-A.; validation, M.N.B.-E.; formal analysis, A.I.M.-A. and M.N.B.-E.; investigation, A.I.M.-A., M.N.B.-E. and F.T.-G.; data curation, M.N.B.-E. and F.T.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.I.M.-A. and F.T.-G.; writing—review and editing, A.I.M.-A. and M.N.B.-E.; supervision, A.I.M.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it did not involve experiments with humans. A first source of data were exams results and were presented anonymously. A second source of data were answers to an anonymous survey.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. Part of these data can be found here: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1TJABEQ_itzomtZ3MwfXmDED5SuAkE9FirnggzSp24jM/edit?resourcekey#gid=1737749487 (accessed on 1 October 2023). Other data are not publicly available because they are students’ tests results.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Blackboard team at the Catholic University of Avila for their technical support during the assessment process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

- Student Survey on The Speaking Test in English via Blackboard Virtual Classroom.

- 1.

- Studies you are currently pursuing.

- 2.

- Sex/Genre

- 3.

- Age

- 4.

- Was this the first time you took a speaking test in English?

- 5.

- Was this the first time you took an online speaking test in English?

- 6.

- What type of computer or device did you use to access the virtual classroom for the speaking test?

- 7.

- When taking an English oral exam, which mode do you prefer: face to face or online? Why?

- 8.

- Are you satisfied with your performance in the speaking test?

- 9.

- If you are not satisfied with your performance, please indicate the reasons.

- 10.

- If you are satisfied with your performance, please state the reasons.

- 11.

- Regarding the examiner’s attitude and gestural feedback… (Choose one). She was too serious and strict, and this did not help me./She was neutral, a mere observer./She was friendly and supportive, and this helped me.

- 12.

- Are you satisfied with your score in the speaking test?

- 13.

- If you are not satisfied with your score, please state the reasons. (Choose one). Because it was too low for what I deserved/Because it was too low, but I deserved it.

- 14.

- In general, do you think that Blackboard’s virtual classroom is a suitable means for taking a speaking test in English? Why?

References

- Magal-Royo, T.; García-Laborda, J. Standardization of Design Interfaces Applied to Language Test on-line through Ubiquitous Devices. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2018, 12, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaven, A.; Neuhoff, A. Assessing oral proficiency for intercultural professional communication: The CEFcult project. The EUROCALL Review. In Proceedings of the EUROCALL 2011 Conference, Nottingham, UK, 31 August–3 September 2011; pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Guedes, A.; Oliveira, I.; Santos, P.; Antunes, S. Foreign languages communicative skills in Secretarial Studies. Practicum 2020, 5, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.D.; Vetahmani, M.E. The impact of online learning in the development of speaking skills. J. Interdiscip. Res. Educ. 2015, 5, 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Eka Prasetya, R. English Teaching Based-Strategy LMS Moodle and Google Classroom: Feature of Testing and Feedback. J. Engl. Teach. Res. 2021, 6, 32–44. Available online: https://ojs.unpkediri.ac.id/index.php/inggris/article/view/15622/2065 (accessed on 11 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gotlib, J.; Jaworski, M.; Wawrzuta, D.; Małkowski, P.; Panczyk, M. Developing public speaking skills in a group of Public Health students with the use of the Microsoft Teams platform. Assessment of the quality of education: A qualitative analysis. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN 22 Conference, Palma, Spain, 4–6 July 2022; pp. 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suputra, D. Teaching English through Online Learning (A Literature Review). Art Teach. Engl. Foreign Lang. 2021, 2, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.; Duckett, D. Universities Confront ‘Tech Disruption’: Perceptions of Student Engagement Online Using Two Learning Management Systems. J. Public Prof. Sociol. 2018, 10, art4. Available online: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jpps/vol10/iss1/4 (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Amin, F.; Sundari, H. EFL Students’ Preferences on Digital Platforms during Emergency Remote Teaching: Video Conference, LMS, or Messenger Application? Stud. Engl. Lang. Educ. 2020, 7, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolova, E.; Rogach, O. Digitalization of Higher Education: Advantages and Disadvantages in Student Assessments. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2021, 10, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, T.; Edwards, R. Exploring the impact of digital technologies on professional responsibilities and education. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 15, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cladis, A.E. A shifting paradigm: An evaluation of the pervasive effects of digital technologies on language expression, creativity, critical thinking, political discourse, and interactive processes of human communications. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2018, 17, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babo, R.; Azevedo, A.; Suhonen, J. Students’ perceptions about assessment using an e-learning platform. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies IEEE, Hualien, Taiwan, 6–9 July 2015; pp. 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulcher, G. Assessing spoken production. In The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching; Liontas, J.I., TESOL International Association, Delli Carpini, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskam, N.N.; Saidalvi, A. Using video technology to improve oral presentation skills among undergraduate students: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 5280–5291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissau, S.; Davin, J.K.; Wang, C. Enhancing instructor candidate oral proficiency through interdepartmental collaboration. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2019, 52, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalise, K.; Wilson, M. The nature of assessment systems to support effective use of evidence through technology. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2011, 8, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senra Silva, I. From language teaching to language assessment with the help of technological resources: Higher Education students and oral production. ELIA Estud. De Lingüística Inglesa Apl. 2022, 22, 93–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñate Cabrera, M. Las tareas de comunicación oral en la evaluación del inglés: El uso de conectores. Rev. de Lingüística y Leng. Apl. 2015, 10, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ortega, M.; Mora, J.C.; Aliaga-García, C.; Mora-Plaza, I. How Do L2 Learners Perceive their Own Speech? Investigating Perceptions of Speaking Task Performance. In Moving beyond the Pandemic: English and American Studies in Spain; Gallardo del Puerto, F., Camus Camus, M.C., González López, J.A., Eds.; Editorial Universidad de Cantabria: Santander, UK, 2022; pp. 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Luchini, P.L.; Ferreiro, G.M. Autoevaluación y evaluación negociada entre docente y alumnos en la clase de pronunciación inglesa: Un estudio con estudiantes argentinos. Didáctica 2018, 30, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, B.; Kamaludin, A.; Romli, A.; Raffei, A.F.M.; Phon, D.N.A.L.E.; Abdullah, A.; Ming, G.L. Blended Learning Adoption and Implementation in Higher Education: A Theoretical and Systematic Review. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2022, 27, 531–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Vigoya, F. Testing Accuracy and Fluency in Speaking through Communicative Activities. HOW 2000, 5, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Borimechkova, D. STANAG 6001 Russian Language Exam: Holistic Approach to Assessing Speaking. Int. Conf. Knowl. Based Organ. 2022, 28, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Aguilar, J.F. Teachers’ Assessment Approaches Regarding EFL Students’ Speaking Skill. Profile Issues Teach. Prof. Dev. 2021, 23, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundqvist, P.; Wikström, P.; Sandlund, E.; Nyroos, L. The teacher as examiner of L2 oral tests: A challenge to standardization. Lang. Test. 2018, 35, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Such, J.; Jornet Meliá, J.M.; Bakieva, M. Consideraciones metodológicas sobre la evaluación de la competencia oral en L2. [Methodological considerations on assessment of oral competence in L2]. Rev. Electrónica de Investig. Educ. (REDIE) 2013, 15, 1–20. Available online: http://redie.uabc.mx/vol15no3/contenido-glez-jornet.html (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Englund, C.; Olofsson, A.D.; Price, L. Teaching with technology in Higher Education: Understanding conceptual change and development in practice. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J. Speaking activities for ESL learners of Odia vernacular schools: Planning, management and evaluation. Res. Sch. 2014, 2, 132–136. Available online: https://researchscholar.co.in/downloads/18-janardan-mishra.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Irawan, R. Exploring the strengths and weaknesses of teaching speaking by using LMS-Edmodo. ELTICS Engl. Lang. Teach. Engl. Linguist. J. 2020, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, E.T. The Effectiveness of Using Blackboard in Improving the English Listening and Speaking Skills of the Female Students at the University of Hail. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2016, 3, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillett-Swan, J. The Challenges of Online Learning: Supporting and Engaging the Isolated Learner. J. Learn. Des. 2017, 10, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albufalasa, M.; Ahmed, M.O.; Gomaa, Y.A. Virtual Learning Platforms as A Mediating Factor in Developing Oral Communication Skills: A Quantitative Study of The Experience of English Major Students at The University of Bahrain. In Proceedings of the 2020 Sixth International Conference on E-Learning (econf), Sakheer, Bahrain, 6–7 December 2020; pp. 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheredekina, O.; Karpovich, I.; Voronova, L.; Krepkaia, T. Case Technology in Teaching Professional Foreign Communication to Law Students: Comparative Analysis of Distance and Face-to-Face Learning. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Applied Linguistics. Foreign Language Assessment Directory. Available online: http://webapp.cal.org/FLAD (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Cabaleiro-Cerviño, G.; Vera, C. The Impact of Educational Technologies in Higher Education. GIST Educ. Learn. Res. J. 2020, 20, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).