Abstract

Foreign language teaching should integrate the culture embodied in the target language. However, raising cultural awareness does not systematically produce the intended effects when considered an integral component in the teaching context. This quantitative research study focuses on creating a catalogue featuring elements representative of British culture in the animated television series Peppa Pig as part of pre-service early childhood education teacher training in English as a Foreign Language (EFL). This prompts the examination of the potential of Peppa Pig to not exclusively enhance EFL proficiency but to foster a comprehensive understanding of British culture for non-native speakers. Eleven pre-service teachers at the University of Cádiz, Spain, analysed the 52 episodes of Peppa Pig’s season 1 and classified all elements into 13 categories, according to the Qualitative Text Analysis approach. To minimise differences between evaluators, each element of each episode was only checked if at least three evaluators agreed; therefore, 1050 elements were identified, with 501 elements verified in 48 of the 52 episodes. The resulting catalogue contributes to selecting the most significant Peppa Pig’s season 1 episodes concerning British culture elements. The major limitation of the investigation may be the fatigue experienced by the evaluators.

1. Introduction

Language and culture are two indivisible elements that mutually define each other [1]. Therefore, language teaching implies the recognition of one or more cultures, attributing significance to the acquisition of the target language and not merely instrumental use [2]. That is, the interrelated nature of language and culture involves that teaching language inherently entails teaching culture, where “culture in language study has to be seen as a way of making meaning that is relational, historical, and that is always mediated by language and other symbolic systems” [3] (p. 71). However, culture still seems to be a marginal element in language teaching [4]. Perhaps language teachers unconsciously avoid addressing any culture, focusing only on the target language itself [5]. Therefore, initial training is appropriate for teachers to become aware of the language–culture relationship in order to apply it in the classroom [6]. Effective training will equip pre-service teachers with a comprehensive understanding of the role of culture in language teaching [7], thus facilitating its integration.

Films, television shows, and cartoons, among others, have been widely used as authentic materials, not only for foreign language teaching but also to provide examples of how to raise cultural awareness among learners [8]. Firstly, research has provided evidence of empirical studies that have proven the benefits of using selected films, television shows, and cartoons to help non-native speakers develop language proficiency [9]. Secondly, much less research has been conducted on the use of films, television shows, and cartoons to develop learners’ cultural awareness, even though some problems have also been identified, as exemplified by Alexiou [10] (for example, understanding films that deal with different patterns of behaviour). In this sense, while films, television shows, or cartoons cannot replace language teachers, they can support learners’ language proficiency and cultural knowledge.

In the case of English as a Foreign Language (henceforth, EFL), perhaps the most investigated animated television series is Peppa Pig. Undoubtedly, it has been one of the most popular British icons since 2004, when it began to be broadcast on television. Moreover, Peppa Pig is a significant reference in the field of research on cartoons as didactic tools for teaching EFL to pre-schoolers [11,12,13,14]. Several empirically proven benefits of Peppa Pig on pre-schoolers’ EFL proficiency have been reported. It is distinguished by the authentic use of the English language, which has been verified by comparing it with existing corpora of real examples [12]. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior study on Peppa Pig has been conducted to analyse the elements of British culture, with the only exception being Kokla’s [14] doctoral thesis. Her study concludes that Peppa Pig “promotes cultural and ethnic diversity and contains an amplitude of cultural and multicultural elements” [14] (p. 137).

This study seeks to analyse all episodes (n = 52) of Peppa Pig’s season 1 with the general objective of creating a catalogue including elements characterising British culture as perceived by EFL pre-service teachers (n = 11) specialising in Early Childhood Education (henceforth, ECE) at the University of Cádiz (Spain). This work holds a dual significance: Firstly, it aids in improving EFL proficiency among pre-service teachers within the specific context of ECE, achieved through the regular watching of Peppa Pig. This exposure not only improves their EFL skills but also cultivates their capacity to analyse potential teaching materials, including animated television series, from the perspective of the target culture. Secondly, in alignment with the general objective, the resulting catalogue highlighting representative elements of British culture serves as a valuable resource for EFL teachers, facilitating the integration of these elements into the ECE classroom.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. English as a Foreign Language Teacher Training in Pre-School Education

EFL teaching in ECE has become one of the major educational initiatives in Spain [15]. Globalisation and its influence on social and professional scenarios have led to the acquisition of additional languages like English [8]. Consequently, several measures have been taken to enhance EFL learning. For example, teaching practices emphasise the development of learners’ communicative competence, not solely linguistic competence [16]. Moreover, there is a widespread commitment to bilingual education, which entails methodological approaches that integrate content and language, involving the use of a target language for authentic communicative purposes [17]. Additionally, there is a collaborative initiative among educational stakeholders, including families, towards the early-age learning of EFL [18]. That is to say, a substantial majority, if not all, members of the educational community are devoted to this endeavour.

Given the distinct attributes intrinsic to school learners in ECE [19], it is essential for educators to undergo tailored training that is specifically geared towards early language acquisition [20]. In a general sense, the process of language acquisition operates without differentiation between first languages and second or foreign languages with regards to cognitive information processing [21,22]. However, the disparity emerges in the degree of exposure to the target language, encompassing both quantitative factors (duration of exposure) and qualitative factors (acquisition options) within language input [23]. Consequently, didactic instruction tailored for subjects like EFL has been seamlessly integrated into the framework of higher education curricula within the Spanish context [24]. Furthermore, empirical support from scientific research corroborates the merits of teaching methodologies grounded in language acquisition principles [25]. Thus, “teachers are or should be viewed as dynamic agents of change” [8] (p. 181), as well as they “have the added advantage of having studied in depth at least one foreign language and culture” [8] (p. 181). Nonetheless, the advantage associated with proficiency in at least one foreign language (for example, EFL) and familiarity with a particular culture “will not suffice if teachers have not had the necessary education and training to support their young learners on their journey to developing their intercultural awareness” [8] (p. 181).

2.2. Cultural Awareness

A significant concern when approaching EFL teaching pertains to the treatment of culture. This might be attributed to the fact that, unlike vocabulary or grammar, as noted by Kovács [26], “culture is more difficult to define; […] it is not clear what and how should be taught” (p. 74). Nevertheless, both language and culture are intrinsic elements, each defining the other [27,28]. In essence, this implies an equality among cultures, an enhanced understanding of one’s own and other cultures, and a focus on the interconnections and differentiations across cultures [29]. Regarding language behaviour, culture encompasses the understanding of how individuals “speak or write to each other, use the tone of their voices, have a certain conversational style, gestures or mimics” [30], among other factors. Moreover, culture entails an awareness of diverse ways of life, traditions, values, and more [31]. Consequently, teacher training should incorporate specific strategies that encompass the holistic treatment of target cultures [32]. This emphasises the importance for learners to recognise cultures beyond their own, a factor that also supports language acquisition [33]. Therefore, as stated by [34], a more comprehensive interpretation of culture, including everything created, produced, or influenced by individuals, should hold relevance in the planning of foreign language teaching.

2.3. Didactic Resources for English as a Foreign Language Teaching and Cultural Awareness

EFL teaching can be enhanced through the use of specific materials or resources [35]. A diverse array of offline and online teaching resources is currently accessible to educators. Among the latter, certain authentic materials were not originally designed for EFL teaching but are now employed for language acquisition objectives, as they contribute to offering genuine cultural experiences [36]. Cartoons serve as an illustration of this phenomenon [8], given their adaptability to learners’ language proficiency levels [36], contingent upon the approach taken by teachers. In this context, various types of cartoons can be employed to foster intercultural learning [8], which involves promoting empathy toward foreigners, illustrating intercultural conflicts, addressing issues of racism, and depicting stereotypes about cultural traditions and intergenerational conflicts, as well as presenting diverse behavioural patterns. One of the most influential cartoon series that makes a significant contribution to the realm of education is Peppa Pig [12], embodying substantial influence from both the perspectives of EFL acquisition and cultural appreciation. Initially, several studies highlighted the educational benefits associated with watching Peppa Pig for the purpose of enhancing EFL proficiency [37]. Also, it has gained considerable recognition, being characterised as the “greatest British import of this decade” [38].

Given this context, the current research study holds significant importance, as it addresses a gap within the existing literature by delving into the potential applicability of animated television series like Peppa Pig. This exploration surpasses the realm of EFL proficiency development, encompassing the mission to acquaint EFL language learners with British culture. The analysis of all episodes (n = 52) constituting Peppa Pig’s season 1, with a focus on identifying elements reflective of British culture, bears a twofold significance. Firstly, this implies a component of the training offered at the university level to pre-service teachers, making them take into consideration the integration of culture into the context of EFL teaching within ECE. Secondly, it seeks to create a catalogue that incorporates the most distinct British cultural elements present in each episode. This catalogue is designed to serve as a valuable pedagogical resource.

3. Objectives and Research Questions

The rationale of this research study was to raise cultural awareness among ECE pre-service teachers and sensitise them to cultural nuances and the interplay between EFL and culture in teaching materials. To achieve this, the general objective consisted of creating, by these pre-service teachers, a catalogue of representative elements of British culture. This catalogue is based on an analysis of all the episodes (n = 52) of Peppa Pig’s season 1.

Operating within the Qualitative Text Analysis approach [39], the central role of research questions within the methodological framework becomes evident. Essentially, it “provides the perspective for the textual work necessary at the beginning, that is, the intensive reading and study of the texts” [39] (p. 45). In the current context, the three research questions displayed below aim to extract insights from the following aspects through quantitative data collection:

- Does Peppa Pig include elements that reflect British culture?

- Which categories of British cultural elements are most prominent?

- Which episodes are particularly suitable for addressing British culture?

4. Methodology

4.1. Context of the Study

The University of Cádiz (henceforth, UCA) is a higher education institution located in the province of Cádiz, Andalusia, Spain. It enrols more than 20,000 students in undergraduate and postgraduate studies. UCA is divided into 17 faculties and schools, along with two affiliated institutions. Among the faculties with the highest student enrolment is the Faculty of Education Sciences. It offers four undergraduate and six postgraduate programs, as well as doctoral studies.

The pre-service teachers who participated in this quantitative methods research are students currently enrolled (2022/23) in a Bachelor’s Degree in Early Childhood Education. The degree is structured into eight semesters over four years, with two full terms exclusively dedicated to curricular placements in schools. Specifically, the evaluators attended a year 3 course: Didactics of Foreign Language in Early Childhood Education-English. This course is optional within the specialisation in Linguistic and Literary Education and aims to achieve the learning goals outlined below:

- To understand the essential components of the foreign language curriculum in preschool education.

- To comprehend and apply the fundamental aspects of communicative competence in the foreign language within preschool education.

- To create instructional approaches for incorporating children’s folklore into the teaching and learning of the foreign language in preschool education.

- To adeptly develop the preschool education curriculum contents with a global perspective in the context of the foreign language.

The course is divided into two modules that are taught concurrently on different days (Mondays and Tuesdays, respectively). Firstly, the initial theoretical module emphasises the didactics of EFL in ECE. Secondly, in contrast to other courses [40], the subsequent practical module aims to enhance the participants’ understanding of EFL teaching, rather than primarily focusing on improving their EFL competence. Finally, participation in this study is a component of the course’s final assessment, accounting for 20% of the final grade. This applies specifically to pre-service teachers who opt for the continuous assessment itinerary.

4.2. Participants

The evaluators (n = 11) that participated in this study constituted the group of pre-service teachers who achieved attendance of 80% or more in the 14 practical sessions of the course. It was conducted during the second term (February–May) of the academic year 2023. Comprising a diverse ensemble, the group included ten women and one man, aged between 20 and 35, holding official EFL certificates ranging from B1 (intermediate) to C1 (advanced) [41]. All were native Spanish speakers, and they had received pre-university education in Andalusia (Cádiz and Málaga, respectively). Moreover, two of them (22%) had undergone primary education (6–12 year olds) in a bilingual school (Spanish–English), while five of them (56%) had undergone compulsory secondary education (12–16 year olds) in a bilingual school (Spanish–English).

In full compliance with the Research Ethics Committee Regulations of UCA, evaluator participation was voluntary and required obtaining their informed written consent. Their data were anonymised and securely stored for evaluation purposes. According to the Research Ethics Committee Regulations of UCA, students’ academic work produced in didactic activities as part of the curriculum may be utilised for research with their explicit written consent [42]. This study adhered to a non-interventional approach, ensuring participant anonymity, in accordance with the Spanish Organic Law 3/2018, dated December 5th, on Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights.

4.3. Procedure and Data Collection

The study involved initially watching and then analysing all 52 episodes of Peppa Pig’s season 1 by eleven different evaluators. Each evaluator was assigned one Peppa Pig episode daily, five days a week (Tuesday to Monday, excluding Saturday and Sunday), for eleven consecutive weeks. They accessed all episodes via digital media (YouTube), identifying British cultural elements they could recognise in each episode. In this respect, no prior definition of culture was provided to the evaluators before commencing the study. The motivation behind this decision was that the evaluators, being university students and future EFL teachers, possessed the capacity to comprehend the implications of culture without requiring an extensive theoretical grasp of the concept when making selections of British cultural elements throughout the episodes. The aim of this training approach was to progressively enhance their comprehension of the concept of culture by means of episode watching and evaluation. Furthermore, each identified British cultural element (without a specified limit per episode) needed to be accompanied by a justification for their choice.

Systematic observation as a quantitative research method was employed to gather data for the present study. Since this method is primarily based on the subjectivity and experience of observers [43], eleven distinct evaluators, as said, who were pre-service teachers sharing coincidental similarities in characteristics (comparable in age, belonging to the same cohort, and sharing a mutual interest in learning English evidenced by their deliberate selection of the course, among other factors), were selected to mitigate the impact of individual differences among the evaluators.

The cultural elements were categorised into 13 categories, one of which was labelled as “Other”. The evaluators were not provided with pre-established categories in advance. Instead, they discerned the British cultural elements within the Peppa Pig episodes. These elements were methodically categorised post-analysis through the Qualitative Text Analysis approach [40]. Following the application of this approach in order to identify and categorise the elements, the ensuing list was compiled. The 13 categories are presented in alphabetical order, accompanied by definitions and various examples. Subsequent to data collection, the results were refined by removing elements unrecognised by less than three evaluators:

- Activities. It refers to elements in connection to in/outdoor activities (excluding food and beverages) and games. For example, read the newspaper in hard copy, ball game, hide and seek, draughts, secret box, etc.

- Infancy. It implies elements concerning children and school. For example, alphabet, the Tooth Fairy, babysitter, the tree house, fete, etc.

- Items. It aims at elements regarding clothing, apparel, gadgets, devices, and machines. For example, top hat, telephone, raincoat, greeting card, newspaper, etc.

- Food. It has to do with elements in relation to food and beverages, excluding activities concerning food and beverages. For example, biscuits, Cullen Skink soup, pumpkin pie, custard doughnut, picnic, etc.

- Housing. It means elements in connection to houses and their surroundings. For example, sitting room, house with garden, vegetable garden, orchard, attic, house roof, etc.

- Language. It refers to elements concerning the English language, such as words, phrases, idioms, expressions, forms of address, etc. For example, “Oh dear!”, “aye aye, captain!”, “Goodness me!”, courtesy titles, “easy as pie”, etc.

- Nature. It focuses on elements as the environment, the Earth, the universe, etc., including animals. For example, flowers in the garden, home production, trees, natural areas, ducks in the ponds, etc.

- Personality traits. It includes elements regarding people’s characteristics. For example, shyness, father’s self-sufficient attitude, gender stereotype, little physical affection, male embarrassment, etc.

- Society. It involves elements in connection to the community, people, civilisation, etc. For example, King or Queen, postman, The Beatles, ice cream lady, detective, etc.

- Traditions. It points at elements in relation to customs and behavioural patterns. For example, preparing lunch, tea party, steering wheel position and way of driving, the doctor goes to the patients’ homes, brick houses, etc.

- Time. It has to do with elements related the parts of the day and the time when activities take place. For example, tea time, breakfsast time, at 19:00 they are already having dinner, sleeping time, dawn, etc.

- Weather. It makes reference to elements in relation to meteorology, climate, temperature, etc. For example, rain, wind, sudden change of weather, snow, muddy paddles, etc.

- Other. It refers to elements that cannot be included in any of the previous categories. For example, train, museum, shopping area, car wash at home, excessively made-up eyes, etc.

Following the collection of raw data, a systematic categorisation was performed based on episodes, evaluators, and categories. By amalgamating the coded data, visual representations such as bar charts, histograms, and tables were generated to illustrate the distribution of the data [44]. Subsequently, a filtering process ensued, leading to the exclusion of elements that did not garner ratification from a minimum of three distinct evaluators. The refined data was then restructured, maintaining its alignment with episodes, evaluators, and categories, and was visualised again utilising bar charts, histograms, and tables to elucidate the distribution of the filtered dataset. Lastly, to discern the trajectory of identified British cultural elements across episodes, a polynomial function was computed to optimally characterise their evolution throughout Peppa Pig’s season 1 episodes. The results of this analysis were summarised in tables, serving as informative references for fellow educators regarding the identified British cultural elements.

5. Results

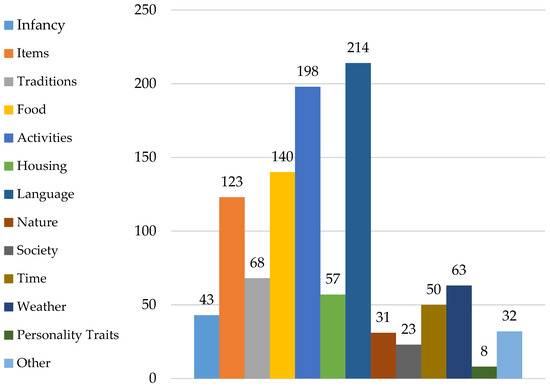

Concerning the overall results of the study, Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 1050 elements identified, classified into 13 different categories.

Figure 1.

British cultural elements identified in Peppa Pig’s season 1.

This figure shows how Language is the most recognised category, closely followed by Activities, while Personality Traits is a very rare category that has only been identified on eight occasions. All categories except Personality Traits have a strong presence in Peppa Pig’s season 1 episodes, which confirms the pedagogical value of the categories considered for this research study. As for the distribution by evaluator, Figure 2 below presents the number of elements of British culture identified by each one of them in the 52 episodes of Peppa Pig’s season 1.

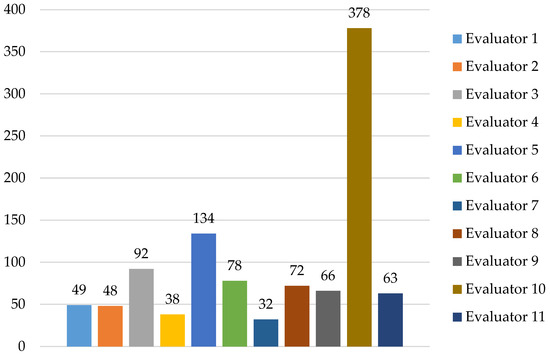

Figure 2.

British cultural elements per evaluator.

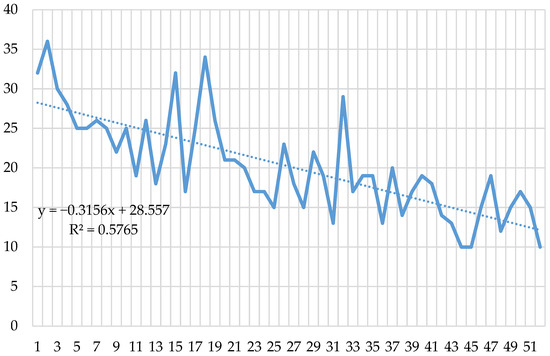

There is a substantial discrepancy between the sensitivity of the eleven evaluators, with evaluator 10 being, by far, the most aware of the different British cultural elements. Thus, verifying the elements identified among several evaluators to reduce individual differences is an appropriate measure that is justified by the distribution of the results. Finally, Figure 3 shows the distribution of all British cultural elements identified per episode in the form of a histogram to facilitate the display of trends, represented by its corresponding polynomial equation.

Figure 3.

British cultural elements identified in each episode.

The distribution of British cultural elements in each episode, as shown in Figure 3, clearly represents a downward evolution as the episodes progress. The trend represented by the data in the polynomial function establishes that this decrease is very pronounced, represented by a negative value of 0.3175. These results represent the evolution of fatigue in the evaluators. Once the overall results of the study were described, the data were filtered by verifying the British cultural elements recognised in each episode by at least three different evaluators. Figure 4 shows the 501 British cultural elements verified according to the 13 categories.

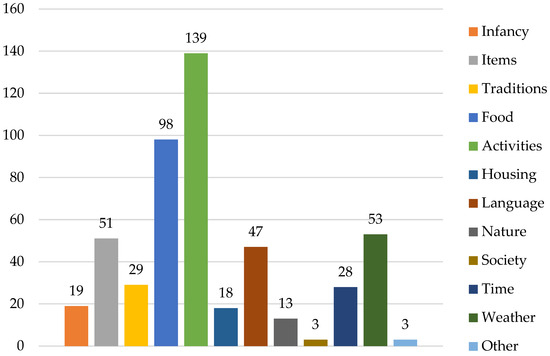

Figure 4.

Verified elements according to the categories.

The distribution of British cultural elements verified according to each category, which can be seen in Figure 4, shows results that are significantly different from the distribution of British cultural elements per category, since the category most identified (Language) drops very sharply. It reveals that three independent evaluators do not agree upon many of the elements identified in Language. The fact that Activities is the most verified category seems to be logical, since Peppa Pig is a cartoon series depicting the everyday life of children. Finally, Table 1 below shows the distribution of British cultural elements verified in each episode, which illustrates the potential pedagogical value of each episode.

Table 1.

Verified British cultural elements per episode.

As can be seen in Table 1, only four episodes (41, 44, 45, and 52) have no verified British cultural elements. Therefore, the distribution of the different categories is wide, and the variety between episodes is considerable, allowing for the educational approach to different contents of EFL and British culture. In this sense, Table 2 below refers to which episodes are the most appropriate to address each category, ranking them according to the degree of agreement between evaluators.

Table 2.

Significant episodes for each category.

Most of the categories can be found in several verified episodes, as shown in Table 2. Thus, it is possible to select different episodes for most of the 13 categories and even treat several categories at the same time. Finally, Table 3 shows the British cultural elements that have been verified the most, representing the most instructive episodes in a specific category, as there would be at least 90% agreement among the evaluators.

Table 3.

Most checked British cultural elements/categories per episode.

6. Discussion

The concept of culture has received considerable attention within the field of EFL teaching, particularly with the explicit aim of raising cultural awareness among learners [8]. Renowned scholars such as Kramsch [3] advocate for defining culture as a “way of making meaning” (p. 71). Consequently, teachers aspiring to integrate culture as an intrinsic facet of EFL teaching must find the need to “identify, explain, classify and categorize people and events according to modern objective criteria and […] the desire to take into account the post-modern subjectivities and historicities of living speakers and writers who occupy changing subject positions in a decentred, globalized world” [45] (pp. 71–72). This stresses the significance of avoiding exclusive associations of cultural elements with conventional clichés. Instead, it becomes crucial to acknowledge the realities defined by “modern objective criteria”, thus considering the facets that characterise a “decentralised and globalised world”. As a result, proposing a catalogue of British cultural elements embedded in Peppa Pig, being the “greatest British import of this decade” [38], emerges as pertinent.

Up to this point, Peppa Pig has appeared as a point of reference within research concerning its potential for facilitating EFL learning. Several studies have proved its benefits, including the following in the ECE context: Alexiou [11] presented a small-scale case study that investigated the influence of comic book series on EFL vocabulary. The results “showed that children were able to recognize many of the words they were exposed to and sometimes even if they had heard them only once” (p. 296). Alexiou and Kokla [12] examined the vocabulary in Peppa Pig and investigated whether this vocabulary is frequent but also appropriate for beginner learners of EFL. They concluded that “the vocabulary size in Peppa Pig is rather large […] The majority of the vocabulary has been found to be infrequent, a fact that shows that there is authentic use of everyday language […] which is relevant and part of pre-schoolers’ world” (p. 28). Scheffler et al. [13] observed the extent to which the language in Peppa Pig contains linguistic features that can also be found in other corpora of spoken English. It proved that “the results do show the potential of the series as an educational tool in pre-primary English instruction” (p. 15). Alternatively, Kokla [37] analysed the effects of Peppa Pig on EFL formulaic language acquisition. This study “showed that mere exposure to the show led to statistically significant differences in formulaic language gains” (p. 87).

However, to the authors’ best knowledge, Peppa Pig has not been thoroughly examined as a potential educational resource for introducing and recognising British culture in the ECE classroom, apart from Kokla’s [14] doctoral thesis titled “The Phenomenon Peppa Pig: A Preschool TV Programme that Promotes EFL Learning, Prosocial Behaviour, Multiculturalism and Gender Equality”. In this work, she argued that “Peppa Pig promotes cultural and ethnic diversity and contains an amplitude of cultural and multicultural elements”, including “British nursery rhymes and songs” (p. 137), which aligns with the Traditions category examined in the current research study. Furthermore, Kokla [14] acknowledged significant cultural elements that coincide with this investigation, such as Weather (“there is much emphasis on the British weather, which is rainy”, p. 138) and Food (“pudding, mince pies, apple and blackberry pies”, p. 138). It is noteworthy to emphasise that both Weather (episodes 1 and 26) and Food (episodes 7, 11, 15, and 29) encapsulate British cultural elements that were validated by nearly all the evaluators. Additionally, Items (episode 18) and Activities (episode 27), which are not mentioned in Kokla’s [14] doctoral thesis, also embody British cultural elements that were recognised by the evaluators.

Although Kokla [14] highlighted cultural elements that are also addressed by the evaluators in the current study, such as British society, traditions, politeness, or mentality (the last two examples would fall under Personal Traits), the category of Language was not considered representative of British culture in her research. Conversely, in the present study, Language takes precedence among the evaluators (n = 214; 20%). Regarding Language and its significance, it is important to emphasise that it “embodies cultural reality” [45] (p. 14). Perhaps this is why the evaluators established direct connections between certain words, phrases, idioms, expressions, and forms of address found in Peppa Pig and British culture. As suggested by Nechifor and Borca [30], this connection is rooted in the “powerful connection established between a society, its users, the language they speak and the culture imbued in it” (p. 290). This signifies, as strongly recommended by Bárdos [34], that EFL speakers in today’s multicultural society should wield the language in alignment with the norms of the respective community as an integral part of their language behaviour.

Finally, the results reveal that not all episodes of Peppa Pig’s season 1 incorporate the same number or types of references to British cultural elements, and not all evaluators exhibit an equal level of cultural awareness. Nevertheless, as highlighted by Kim [46], “to create language pedagogy that facilitates more effective intercultural communication, we must have an adequate account of culture” (p. 521). For at least ten evaluators, the following British cultural elements stand out: Weather (episodes 1 and 26); Food (episodes 7, 11, 15, and 29); Items (episode 18); and Activities (episode 27). In essence, these elements are recurrently featured in the episodes of Peppa Pig’s season 1, making them particularly applicable to the EFL classroom in ECE. However, various other elements, classified within distinct categories, have also been identified. These contribute to the cultivation of cultural awareness and encompass Children, Traditions, Housing, Nature, Society, Time, etc. As expressed by [8], “the fact that children have not yet developed many inhibitions and stereotypical images of the ‘other’, further lends itself to unique opportunities to cultivate understanding and appreciation” (p. 178), often through mediums like films, television series, or cartoons like Peppa Pig [14]. Moreover, Kramsch [1] suggested that “films stimulate multi-sensor and cognitive channels and thus a great source of intercultural information that can appeal to both the viewer’s senses and cognition […]. Watching films, television series, cartoons, etc., provides ample opportunities for the teachers and the students to engage in meaningful discussions, reflection, and in certain cases, debriefing” (pp. 179–180). Indeed, as stated by Kramsch [47], the language teacher will be characterised “not only as the impresario of a certain linguistic performance, but as the catalyst for an ever-widening critical cultural competence” (p. 90). In addition to enhancing learners’ EFL proficiency, Peppa Pig can also function as a catalyst for “engaging in meaningful discussions, reflection, and debriefing” (p. 180), particularly in relation to British cultural elements, as evidenced by the current findings.

7. Conclusions

The objective of this research study was to analyse all episodes of Peppa Pig’s season 1 to identify and classify British cultural elements. This was successfully implemented as part of pre-service teachers’ training to consider the options of using Peppa Pig in the ECE classroom to develop learners’ EFL proficiency and raise cultural awareness. Eleven evaluators identified 1050 British cultural elements that were classified into 13 categories, which yielded a positive affirmation in response to research question 1 (Does Peppa Pig include elements that reflect British culture?). The statistical analysis allowed classifying the most significant episodes in terms of the highest number of British cultural elements and the typologies of the categories. Consistent with the evaluators, Language is the category that gathers the highest number of elements. Likewise, Weather, Food, Items, and Activities are the most easily recognisable categories for almost all the evaluators, at least regarding the episodes presented in Table 3, which serves to address research questions 2 (Which categories of British cultural elements are most prominent?) and 3 (Which episodes are particularly suitable for addressing British culture?), respectively. As a result, Peppa Pig, at least for season 1, includes elements representative of British culture. It can be considered as authentic material for the development of EFL proficiency and cultural awareness raising in the ECE classroom. Nonetheless, the current study does not propose specific methodologies for the utilisation of Peppa Pig. Instead, it underscores the presence of inherent British cultural elements within the content, which possess the potential for strategic teaching exploitation.

The most evident limitation of this study relates to the evaluators’ fatigue in systematically analysing Peppa Pig episodes in order to identify British cultural elements. This could have negatively affected the analysis of the last episodes, considering the amount of 52 episodes. In this regard, it is important to recall that the pre-service teachers were assigned the responsibility of evaluating one episode per day, five days a week (Tuesday through Monday, excluding Saturday and Sunday), as directed by the lecturer–course coordinator (it should be noted that a Peppa Pig episode has an approximate duration of 5–6 min). Another limitation is that all evaluators are pre-service teachers, so they do not have a solid knowledge of EFL yet, nor of British culture, maybe beyond stereotypical clichés inherited from their mainstream culture about what Britishness represents. Nevertheless, as pointed out, the objective of this training was to gradually enhance their self-comprehension of the cultural concept through the observation and evaluation of Peppa Pig episodes. Finally, when analysed from a teacher training perspective, it is essential to understand that facilitating pre-service teachers in recognising the interrelationship between language and culture does not necessarily imply their competence in utilising or approaching this subject with pupils. While gaining a deeper comprehension of the cultural elements might indeed motivate teachers to incorporate it as an educational resource, it does not provide them with working models for systematic treatment.

With this in mind, a future line of research could imply reducing the number of episodes to be examined in order to be more analytically precise, although this study also implied a continuous exposure to EFL as part of the pre-service teachers’ training. In addition, there is the option of analysing a contemporary animated television series other than Peppa Pig and finding out about possible new cultural elements. This would significantly influence the approach towards cultural integration within the ECE classroom. Specifically, culture would be methodically incorporated as an integral component of EFL lessons, enhancing an updated use of the target language. This orientation is not limited to outdated conventional EFL usages, as highlighted by Pérez-Cañado [48], who characterised it as the “It’s raining cats and dogs syndrome”. An additional line of future research would imply the examination of perceptions regarding the British cultural elements included in Peppa Pig. These perceptions are not solely contingent upon the intrinsic content of the animated series itself. Therefore, engaging students from a distinct national background becomes significant, as the results derived from this prospective study could potentially manifest variations compared to the findings of the present work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.E.-C. and R.S.-C.; methodology, J.L.E.-C.; software, R.S.-C.; validation, J.L.E.-C. and R.S.-C.; formal analysis, J.L.E.-C. and R.S.-C.; investigation, J.L.E.-C.; resources, J.L.E.-C.; data curation, J.L.E.-C. and R.S.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.E.-C.; writing—review and editing, J.L.E.-C. and R.S.-C.; visualization, J.L.E.-C. and R.S.-C.; supervision, J.L.E.-C. and R.S.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In accordance with the Plan Propio de Estímulo y Apoyo a la Investigación y Transferencia 2022/2023 (Plan of Stimulation and Support for Research and Transfer), the University of Cádiz is dedicated to fostering and advancing the dissemination of knowledge among its student body. This commitment, derived from the specific tenets of Pilar I in the Plan, significantly encourages and promotes the active involvement of student teachers in research endeavours. This initiative serves as a pivotal element in nurturing the foundational skills of students interested in embarking on research endeavours. Moreover, the general objective of this research was the creation of an aseptic catalogue, devoid of personal data, thereby eliminating any potential harm to the student teachers themselves or any third parties involved. Consequently, this research lies beyond the purview of intervention by the research committee at the University of Cádiz.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kramsch, C. Language and Culture. AILA Rev. 1994, 27, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCapua, A.; Wintergerst, A.C. Crossing Cultures in the Language Classroom; University of Michigan Press ELT: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kramsch, C. Culture in foreign language teaching. Iran. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2013, 1, 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Azizmohammadi, F.; Kazazi, B.M. The importance of teaching culture in second language learning. Asian J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2014, 2, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Chen, D. Two barriers to teaching culture in foreign language classroom. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2016, 6, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razı, S.; Tekin, M. Role of culture and intercultural competence in university language teacher training programmes. Asian EFL J. 2017, 19, 29–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell, T. Teaching about teaching about culture: The role of culture in second language teacher education programs. Electron. J. Engl. A Second. Lang. 2019, 22, n4. [Google Scholar]

- Karras, I. Raising intercultural awareness in teaching young learners in EFL classes. Res. Pap. Lang. Teach. Learn. 2021, 11, 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaus, M.; Alishahi, A.M.; Chrupała, G. Learning English with Peppa Pig. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2022, 10, 922–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roell, C. Intercultural training with films. Engl. Teach. Forum 2010, 48, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiou, T. Vocabulary uptake from Peppa Pig: A case study of preschool EFL learners in Greece. In Current Issues in Second/Foreign Language Teaching and Teacher Development: Research and Practice; Gitsaki, C., Alexiou, T., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2015; pp. 285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiou, A.; Kokla, N. Cartoons that make a difference: A linguistic analysis of Peppa Pig. J. Linguist. Educ. Res. 2018, 1, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffler, P.; Jones, C.; Dominska, A. The Peppa Pig television series as input in pre-primary EFL instruction: A corpus-based study. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 2021, 31, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokla, N. The Phenomenon Peppa Pig: A Preschool TV Programed That Promotes EFL Learning, Prosocial Behaviour, Multiculturalism and Gender Equality. Ph.D. Thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece, September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Andúgar, A.; Pérez-Cortina, B.; Tornel, M. Tratamiento de la lengua extranjera en Educación Infantil en las distintas comunidades autónomas españolas. Profesorado Rev. Currículum Form. Profresorado 2019, 23, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleta, T. From research on child L2 acquisition of English to classroom practice. In Early Instructed Second Language Acquisition: Pathways to Competence; Rokita-Jaśkow, J., Ellis, M., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2019; pp. 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, A.; Cortina-Pérez, B. Handbook of CLIL in Pre-Primary Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolov, M.; Mihaljević, J. Studies on pre-primary learners of foreign languages, their teachers, and parents: A critical overview of publications between 2000 and 2022. Lang. Teach. 2023, 56, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, F.; Cohrssen, C.; Vidmar, M.; Segerer, R.; Schmiedeler, S.; Galpin, R.; Valeska, V.; Kandler, S.; Tayler, C. Early childhood professionals’ perceptions of children’s school readiness characteristics in six countries. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 90, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfenninger, S.E.; Singleton, D. Making the most of an early L2 starting age. J. Lang. Teach. Young Learn. 2019, 1, 111–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowska, E.; Divjak, D. Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics. Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science, 39th ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska, E. Between productivity and fluency: The fundamental similarity of L1 and L2 learning. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference Thinking, Doing, Learning: Usage Based Perspectives on Second Language Learning, Jyväskylä, Finland, 17–19 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, S. Quantity and quality of language input in bilingual language development. In Bilingualism across the Lifespan: Factors Moderating Language Proficiency; Nicoladis, E., Montanari, S., Eds.; De Gruyter: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Alfaro, E.; Zayas-Martínez, F. Identidad docente y formación inicial. El maestro generalista, el especialista de lengua extranjera y el maestro AICLE en un proyecto lingüístico de centro. In Higher Education Perspectives on CLIL; University of Vic—Central University of Catalonia: Vic, Spain, 2014; pp. 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Loewen, M.; Sato, M. The Routledge Handbook of Instructed Second Language Acquisition; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, G. Culture in language teaching: A course design for teacher trainees. Acta Univ. Sapientiae Philol. 2017, 9, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sercu, L.; Méndez-García, M.C.; Castro, P. Culture teaching in foreign language education. EFL teachers in Spain as cultural mediators. Porta Linguarum 2004, 1, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.T.K. Addressing culture in EFL classroom: The challenge of shifting from a traditional to an intercultural stance. Electron. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. 2009, 6, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, B.; Musuhara, H. Developing cultural awareness. MET 2004, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nechifor, A.; Borca, A. Contextualising culture in teaching a foreign language: The cultural element among cultural awareness, cultural competency and cultural literacy. Philol. Jassyensia 2020, 2, 287–304. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, M.; Gribkova, B.; Starkey, H. Developing the Intercultural Dimension in Language Teaching. A Practical Introduction for Teachers. Language Policy Division; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2002; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16802fc1c3 (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- López-Hernández, A. Initial teacher education of primary English and CLIL teachers: An analysis of the training curricula in the universities of the Madrid Autonomous Community (Spain). Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2021, 20, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alptekin, C. Towards intercultural communicative competence in ELT. ELT J. 2022, 56, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárdos, J. (Ed.) Kulturális kompetencia az idegen nyelvek tanításában [Cultural competence in foreign language teaching]. In Nyelvpedagógiaitanulmányok [Studies in Language Pedagogy]; Pécs: Iskolakultúra; Élő Nyelvtanítás-Történet [A Living History of Language Teaching]; Nemzeti Tankönyvkiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 2005; pp. 142–157. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, B. Materials Development in Language Teaching; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, E.; Coltrane, B. Culture in second language teaching. In Culture in Second Language Teaching; Eric Clearinghouse on Languages and Linguistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kokla, N. Peppa Pig: An innovative way to promote formulaic language in pre-primary EFL classrooms. Res. Pap. Lang. Teach. Learn. 2021, 11, 76–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shakhnazarova, N. Quentin Tarantino Calls Peppa Pig ‘Greatest British Import of This Decade’. Available online: https://nypost.com/2022/07/07/quentin-tarantino-calls-peppa-pig-greatest-british-import-of-this-decadequentin-tarantino-calls-peppa-pig-the-greatest-british-import-of-this-decade/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Text Analysis: A systematic approach. In Compendium for Early Career Researchers in Mathematics Education; Kaiser, G., Presmeg, N., Eds.; ICME-13 Monographs; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Chichón, J.L.; Zayas-Martínez, F. Dual training in language didactics of foreign language/CLIL pre-service primary education teachers in Spain. J. Lang. Educ. 2022, 8, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Plan Propio de Estímulo y Apoyo a la Investigación y Transferencia 2022/2023; University of Cádiz: Cádiz, Spain, 2022; Available online: https://planpropioinvestigacion.uca.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/PLAN-PROPIO-22042022.pdf?u (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Scope, A.; Dusza, S.W.; Halpern, A.C.; Rabinovitz, H.; Braun, R.P.; Zalaudek, I.; Argenziano, G.; Marghoob, A.A. The “ugly duckling” sign: Agreement between observers. Arch. Dermatol. 2008, 144, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Cabrero, R.; Barrientos-Fernández, A.; Arigita-García, A.; Mañoso-Pacheco, L.; Costa-Román, O. Demographic Data, Habits of Use and Personal Impression of the First Generation of Users of Virtual Reality Viewers in Spain. Data Brief 2018, 21, 2651–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramsch, C. Language and Culture; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D. Learning language, learning culture: Teaching language to the whole student. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2020, 3, 519–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramsch, C. The cultural component of language teaching. Lang. Cult. Curric. 1995, 8, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cañado, M. Enseñanza bilingüe: Inclusión y excelencia. In Proceedings of the VIII Congreso Internacional de Enseñanza Bilingüe en Centros Educativos, Jaén, Spain, 21–23 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).