Abstract

Serious games (SGs) provide an opportunity to address social issues in an interactive environment that is particularly appealing and engaging for school-aged children. Gender stereotypes are one of the most prevalent gender-related issues in current society. Stereotypes appear at early ages and are a global problem, even if they are particularly prevalent in certain cultures and countries. This paper presents an early acceptance evaluation of Kiddo, a serious game, to address gender stereotypes in Mexico. The game has been designed to address four of the main gender stereotypes still present in children in Mexico, and it is intended to be used in classes by teachers to provide a common experience for the class and to start a discussion about gender stereotypes. The evaluation was carried out with a prototype of the game and consisted of two separate stages. First, we verified both the usability of the game and its acceptance with a sample including teachers and gender experts (10 participants). Second, we carried out a complete formative evaluation with teachers (32 participants) who will oversee the later application of the game to ensure their acceptance of the game as a tool to use in their classes. The initial results of both usability and acceptance questionnaires are promising and have provided a useful insight into the strengths and areas of improvement for the game, and they are being incorporated into the final version of Kiddo. Besides improving the game, these results are additionally being used to better understand teachers’ perspectives and enrich the companion teacher pedagogic guide to simplify the game application in the classroom.

1. Introduction

This article is an extension of the ICWL–SETE conference paper “Acceptance evaluation of a serious game to address gender stereotypes in Mexico” [1]. The conference paper was an early description of the first acceptance evaluation of the game, whereas we have extended the article with a new formative evaluation with teachers to ensure their acceptance of the game to be later used in their classes.

This article describes the process of the creation and acceptance of Kiddo, a videogame used to educate about gender equality. A prototype of the game was created and evaluated, looking for areas of opportunity to improve before completing the videogame and launching it to the public. Particularly, we wanted to first address teachers’ acceptance of the game, as once the game is completed and ready to use in classes, teachers will oversee its application. Therefore, it is essential that teachers see the Kiddo videogame as a useful educational tool to apply in their classes.

The main goal is that all recommendations and results presented by teachers and experts will be incorporated into the new version of the Kiddo game, as well as into the pedagogical guide that will be provided to teachers (together with the game), to simplify future applications of the game in the classroom.

The specific purpose of the research is to develop and successfully implement Kiddo, a serious videogame used to support teachers in better providing an equal education for girls and boys.

2. Related Work

2.1. Serious Games

Serious games (SGs) are games that have a main purpose other than entertainment, enjoyment, or fun [2]. Among their purposes, the ones that stand out are increasing awareness, teaching knowledge, or changing behavior. The highly interactive environment that they provide allows many possibilities for affecting their players, including immersive learning experiences to apply their knowledge and/or test complex scenarios in a safe and controlled environment. Due to these characteristics, SGs have been applied in different domains with promising results, including applications in the e-health field and to address social problems [3].

Nowadays, serious games are becoming widely used in the research community. These games are promising tools thanks to the engagement between stakeholders, the potential for interactive visualization, and the capacity for developing and improving social learning and teaching decision-making skills [4]. Although serious videogames are not new, their expansion has been taking place since 2010. Researchers suggest that the characteristics of serious videogames should establish clear learning objectives for students, provide continuous feedback on their progress, and adapt their difficulty to the learner’s capabilities, as well as adding surprise elements to break the monotony of the videogame [5].

2.2. Gender Stereotypes

One of the remaining gender-related issues in current society is the prevalence of several gender stereotypes. The United Nations’ Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights defines a gender stereotype as “a generalized view or preconception about attributes or characteristics, or the roles that are or ought to be possessed by, or performed by, women and men” [6]. These preconceptions limit individuals’ development and choices and perpetuate inequalities. Even if this is a global issue, in certain cultures and countries, the presence of gender stereotypes is particularly striking. Such is the case in Mexico, where different reports have studied the prevalence and normalization of gender stereotypes in general society as part of the cultural background [7], and their direct relation to sexist and gender stereotypes in primary and secondary students. Some of these reports highlight the most common stereotypes among Mexico’s children [8], summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main results of questionnaire applied to a representative sample of Mexico’s sixth grade primary school children (adapted from the original, in Spanish [8]).

Gender stereotypes appear very early in children’s development, so it is essential to address them at a young age because those stereotypes could have a big impact on important aspects of their lives, such as education, thus limiting their future opportunities. This happens to be especially noticeable in Latin American culture. In a study [9] aimed at determining the role and level of involvement of Latin American mothers in their children’s math learning, the results showed that the mother’s attention regarding their daughter’s math learning decreased overtime, especially during fifth and sixth grade, a situation paired with statements such as “math is more useful for boys”. Another study [10] carried out with younger children mentioned that mothers of children around two years of age use language related to numbers (initial mathematical approach) up to three times more with boys than with girls.

As a result, at early school ages, the stereotype that “girls are better at reading and boys are better at mathematics” is reinforced. Although, as mentioned, this is a stereotype, it causes frustration on both sides: for the girls for “not being as good” and for the boys who have difficulties with mathematics due to “not being as good as the other boys”.

2.3. Serious Games to Address Gender Issues

Serious games have been used to address gender issues, such as violence or abuse. Examples of this are Tsiunas [11], a game used to understand essential elements for the prevention of gender-based violence and the promotion of responsible masculinities, and Jesse [12], an adventure game set in the Caribbean region that deals with domestic violence. Other examples of gender-focused videogames are Berolos [13] (Spain) and Iguala-t [14] (Spain). Some of these games have had academic evaluations that measured their effectiveness, with most of them being demonstrated as successful tools that, using their approach, help counteract gender problems. There are three main approaches that most of the games addressing gender issues tend to use.

- Games for girls deal with gender differences and promote different concepts of femininity.

- Games designed to change gender stereotypes have the approach of creating awareness regarding sexism and gender stereotypes.

- Creative games are developed mostly for girls, encouraging girls to create and develop their own learning conditions and surroundings. Widely used in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math), such projects are focused on bringing girls closer to the sciences [15].

In a review of games addressing gender-related issues [16], the results showed that stereotypes were barely mentioned. Only the videogame Chuka [17], developed by The United Nations Office against Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in Mexico, included gender stereotypes as one of the topics addressed in the game.

The results also showed the limitations of the games in addressing gender issues: the scarce number of evaluation studies to prove their effectiveness, the scarce follow-up to measure their long-term effect, and the lack of participants and evaluations with teachers or educators who can apply the games in their classes. Despite these limitations, we consider that serious games provide multiple advantages, one of the most relevant ones being the possibility to include an analysis of the players’ interactions. This allows us to study the data collected by the game with the objective of investigating if there are changes with respect to the perception of the problem presented to the users before and after applying a game, videogame, or simulation in which they suffer some discrimination or confrontation regarding gender stereotypes.

Focusing on these characteristics, we developed Kiddo, a serious game to address gender stereotypes, which has been evaluated with teachers to test its acceptance and applicability, as described in the following sections.

3. Design and Development of the Kiddo Project

3.1. About the Kiddo Game

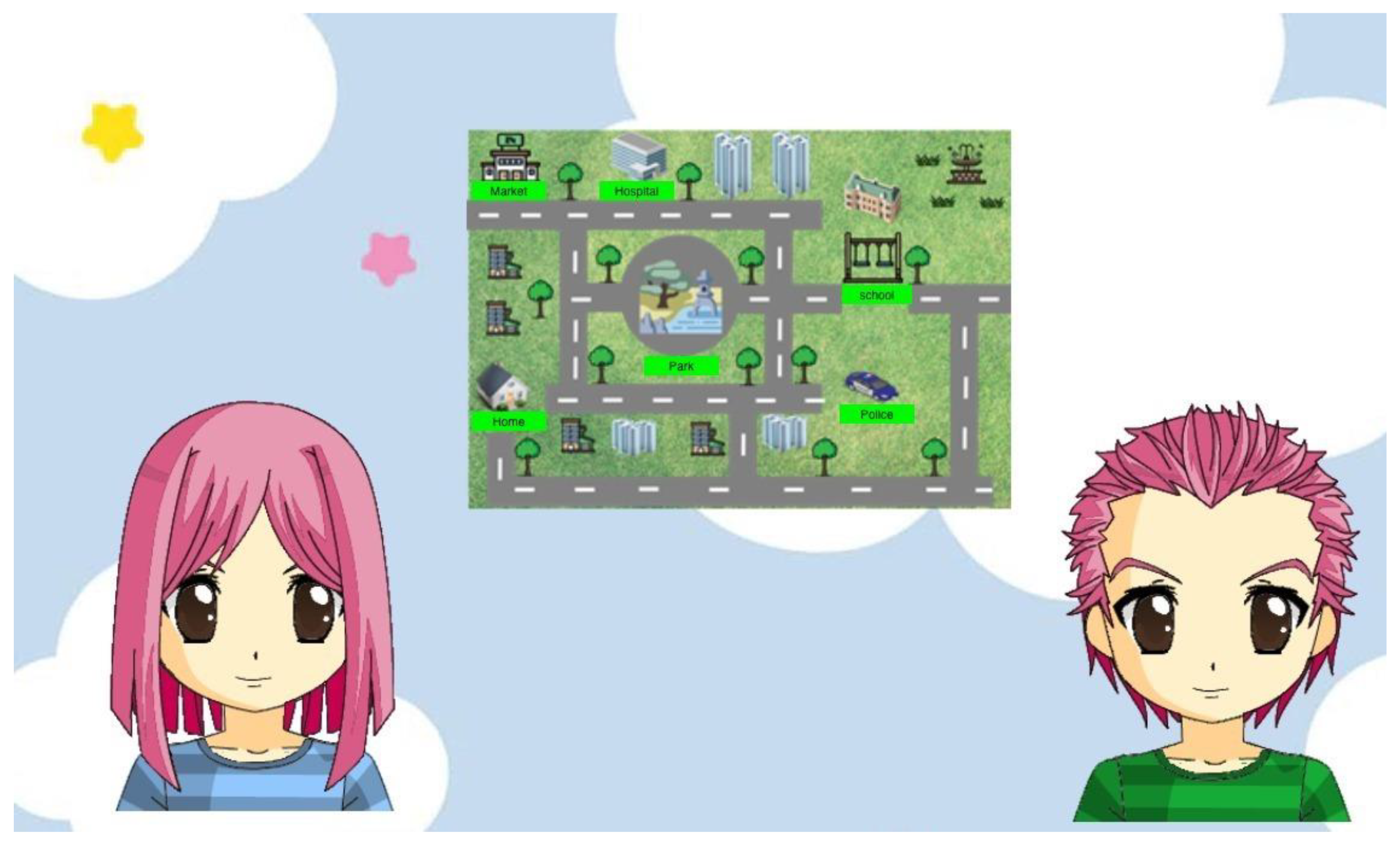

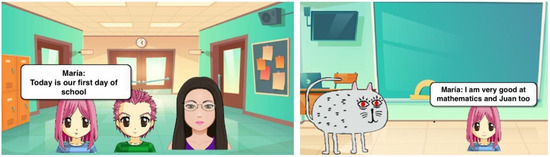

Kiddo is a narrative and decision-making or “game thinking” videogame used to address gender stereotypes for school-aged children (9–13 years old). Kiddo seeks to make the most common gender stereotypes visible so as to educate about equality. The story takes place in common scenarios in a child’s development: school, home, park, etc. The main characters of the game are two twins (a boy and a girl) who encounter situations related to gender stereotypes that they must overcome without hurting themselves or the other twin. In these scenarios, the twins, Juan and María (see Figure 1), engage in conversations and interactions with other characters (NPC/non-playable) within the game. The game has a mood bar, where players can observe how the character feels about the decisions made.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of Kiddo showing the twins (left and right) and the scenarios of the game (center).

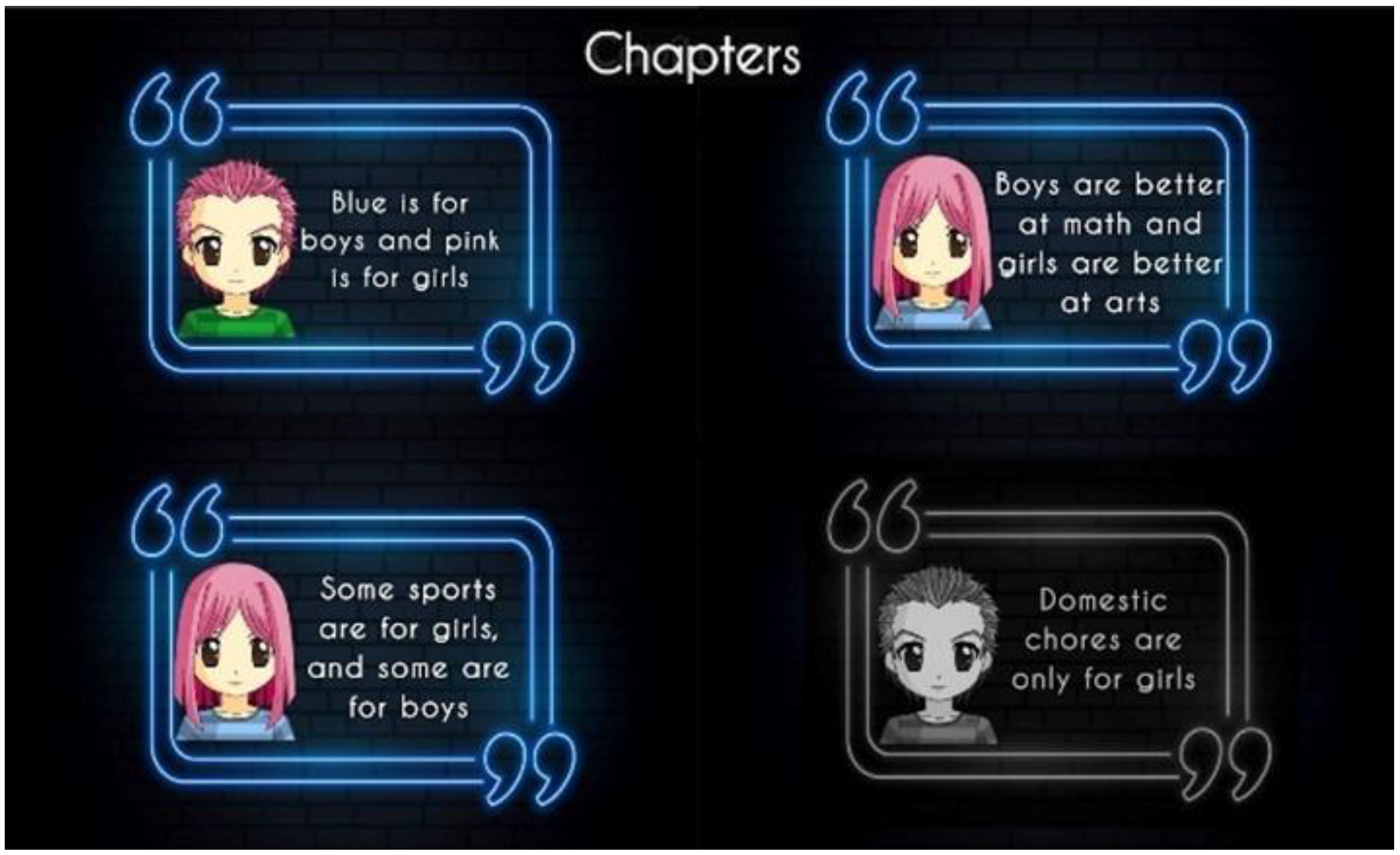

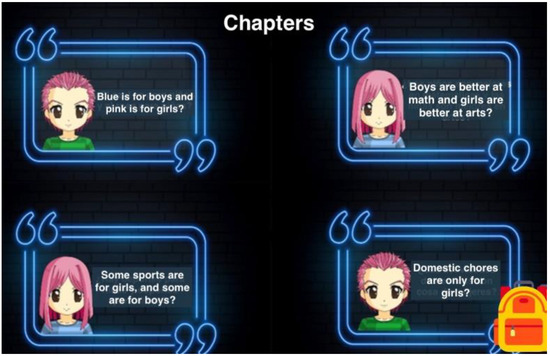

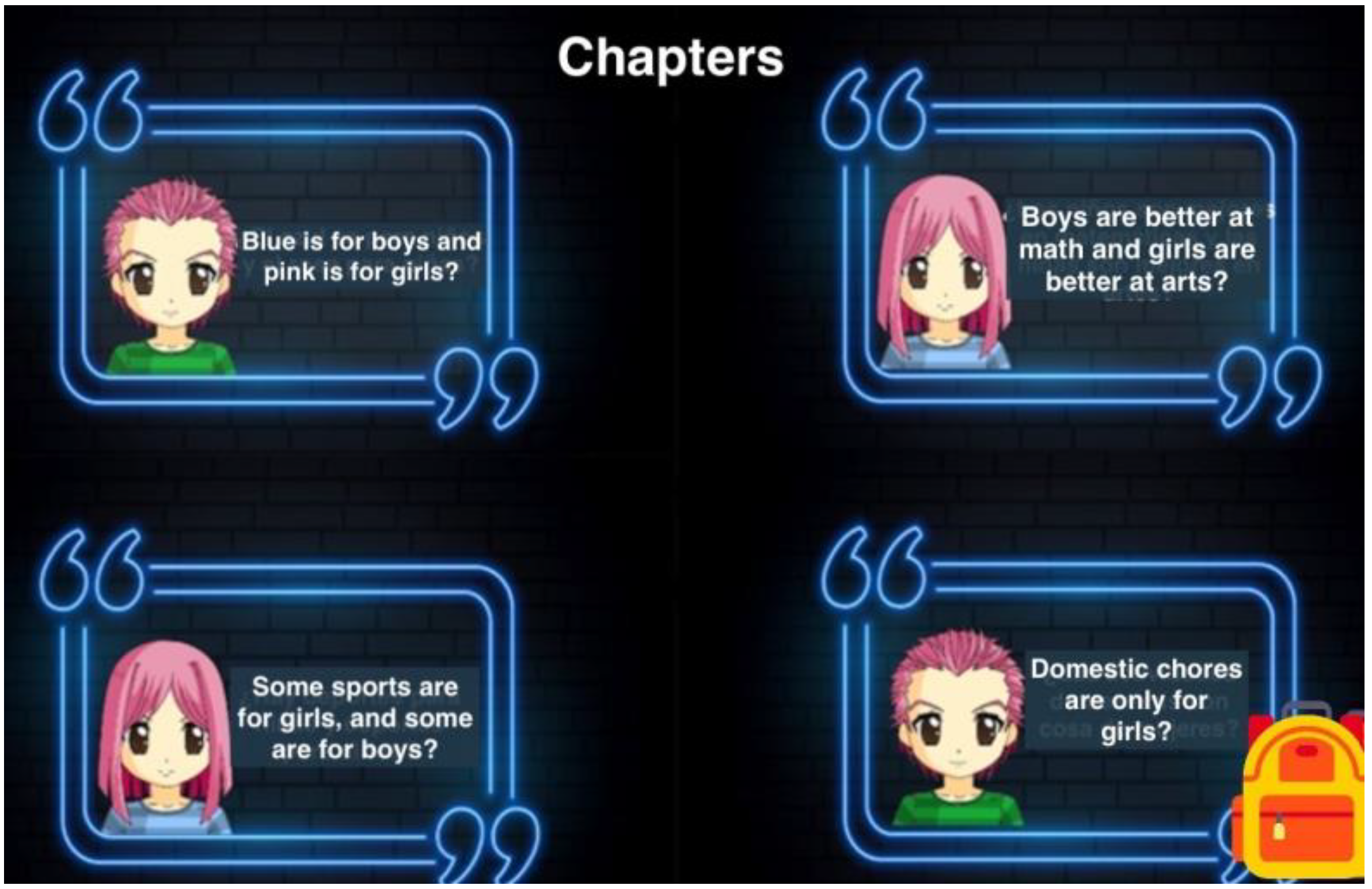

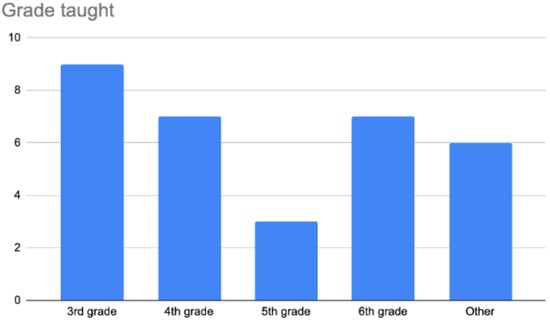

Players play from a third-person perspective, achieving immersion in the game through elements such as narrative, character design, and the use of common environments for the players, which can help increase a sense of empathy and closeness in a player. The game contains four chapters (see Figure 2) addressing different gender stereotypes:

- Colors: “Blue is for boys and pink is for girls”;

- Educational: “Boys are better at math and girls are better at arts”;

- Physical activities: “Some sports are for girls, and some are for boys”;

- House activities and responsibilities: “Domestic chores are only for girls”.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of Kiddo’s twins and gameplay with four available chapters (translated from Spanish).

Figure 2.

Screenshot of Kiddo’s twins and gameplay with four available chapters (translated from Spanish).

Each chapter is designed to last 10 min at the maximum, and thus the whole game, including any pre-game and post-game interventions, can be played in a single lesson lasting hour. In two of the chapters (colors and domestic chores), players will make decisions affecting Juan (the twin boy), while in the other two chapters (educational and physical activities), the choices made by the players will affect María (the twin girl).

3.2. Design and Development

The design of Kiddo was based on a review of the previous literature regarding serious games and gender stereotypes, as well as on an analysis of multiple games addressing gender-related issues and other social issues. The common characteristics and mechanics of such games helped in the early design of Kiddo.

Before the evaluations and during the design phase, chapter 1 (or the pilot chapter) of Kiddo was evaluated by four experts in serious videogames from the research group, each researcher playing the game independently, and all of whom had not participated in the design and/or development of the game. Their comments and suggestions were analyzed, and the game was revised to improve several aspects of the chapter, including the design of some items and NPCs, the dialogues in some conversations, a better description of the gender stereotypes addressed, and some other minor suggestions.

- I.

- The first evaluation (usability and acceptance evaluation)

The first test, including chapter 1, was carried out by internal and external participants: members of the authors’ research group, teachers, students, parents, videogame players, and non-videogame players, with the purpose of testing the design of Kiddo and evaluating its acceptance and usability for target users (particularly teachers) and gender experts, obtaining constructive comments to improve Kiddo’s early development.

- II.

- The second evaluation (formative evaluation with teachers)

The updated version of Kiddo, including chapters 1, 2, and 3, was evaluated by teachers at elementary schools in Mexico. These evaluators are essential because they will be responsible for the actual game administration and use in classrooms. This new version of the game includes all the suggestions that were received to achieve the final version of Kiddo.

In both cases, a data analysis was performed by the authors of this article to try and minimize any possible bias (every result was reviewed by at least two members of the authors’ research group).

Kiddo was developed using uAdventure [18], a framework built on top of Unity to design educational videogames. uAdventure simplifies game development by abstracting the main narrative elements of “point and click” adventure games (e.g., scenarios, characters, and conversations) into a simplified, easy-to-understand model, allowing non-expert game developers to focus on the features they need. uAdventure further incorporates default game learning analytics [19] that traces from all player-related events to be collected (e.g., interactions with game elements and NPCs; scene changes; start, ending, and choices in conversations; and changes in game-state variables). These incorporated learning analytics will be essential in the subsequent validation of the final version of Kiddo when it is tested with actual students. Due to uAdventure multiplatform features, Kiddo’s final version will be available on several platforms, currently including PC (Windows) and mobile devices (Android). Those are the platforms most frequently used in schools in Mexico.

3.3. Chapters of Kiddo

Kiddo is a narrative game structured in chapters, each of which addresses a particular gender stereotype.

The story begins in the first chapter (see Figure 3) with the family arriving in a new town and entering their new house. Despite being twins, Juan and María start to feel as though people are treating them differently because of their sex. In the first chapter, the players make decisions regarding Juan (the twin boy) and the color used to paint his bedrooms’ walls. Juan’s desire is to use a pink color for his room, and for the first decision crossroad, players have to decide whether pink is a suitable color for Juan’s bedroom’s walls or if a different color will be more suitable for him. During this chapter, players can decide on the color on multiple occasions and have to face different opinions regarding this stereotype; in particular, the twins’ father is against painting Juan’s bedroom walls pink (“men do not use pink, it is a color for girls”), while the twins’ mother has a more open attitude towards it. In the end, however, the decision falls on the player and, after facing different opinions and comments, they can change their initial opinion and decide whether they want to choose pink or another color.

Figure 3.

Screenshots of Kiddo’s first chapter, including characters’ dialogues (left) and the final monster (right).

In the second chapter (see Figure 4), the parents are looking for ways to get the twins into a recreational activity to meet more people, so they approach a cultural center. The parents suggest that the twins perform a sports activity that will allow them to make friends and develop healthily. However, during the selection of sports activities, the first crossroad regarding sports gender stereotypes arises. The stereotype presented in this chapter states that “there are sports for girls and sports for boys”. In this chapter, Maria decides she wants to be a boxer, and then the first disagreement arises since Maria’s father does not agree that she should practice a sport that is, in his words, “clearly for boys”. He also points out that Juan, her brother, is the one who should take care of Maria´s safety. In this chapter, players have to face several comments and opinions, based on which they can decide whether Maria should or should not practice boxing.

Figure 4.

Screenshots of Kiddo’s second chapter, including characters’ dialogues (left) and the final monster (right).

In the third chapter (see Figure 5), players face another crossroad, this time at the elementary school, where the art and science fair is taking place. In this chapter, Maria’s wish is to participate in the science area; however, the teacher has decided to divide the group in two based on the students’ gender. Particularly, the teacher explains to female students that it is better for women to participate in areas traditionally closer to their sex, such as art, while for boys, the teacher tells them that it is better for them to compete in science and mathematics. During this chapter, players have to face different opinions about this stereotype, while the teacher is still rooted in the old stereotype “boys are better in math and girls are better in arts”. The children have to face these stereotypes with the help of their classmates, so as to try and change the way the twins will participate in the fair.

Figure 5.

Screenshots of Kiddo’s third chapter including characters’ dialogues (left) and the final monster (right).

In all the game chapters, early decisions determine whether players achieve the “heart of courage”, a game item that will help them fight the monster that appears at the end of the chapter. By using the heart or finally choosing to fight the stereotype, players can defeat the monster in each chapter. In the case that they still agree with the gender stereotype, they cannot defeat the monster and are directed to a short video explaining the stereotype—for instance, why colors are gender neutral.

The initial chapter was presented to the primary education directorate, “Dirección de Educación Primaria”, in Mexico City to receive feedback about applying the videogame in public schools located in vulnerable areas of Mexico City. We received the following feedback:

- The Kiddo game, which is based on stereotypes and roles commonly associated with gender, a topic especially relevant nowadays, must contain language that is easy to understand for children.

- The Kiddo game should complement and expand the equality education of the Secretary of Public Education programs, such as the one contained in Block 2, Sequence 3 (Building Equality Together) of the Civic and Ethical Formation book for third grade, edited by the Ministry of Public Education.

- The Kiddo game can be applied to groups in the fourth grade and later.

- Before being applied, Kiddo must be reviewed and approved by the General Directorate of Operation of Educational Services.

Considering these requirements, the book “Third Grade Civic and Ethical Formation” was studied, and we fully revised the four chapters of the game to align them with the didactic objectives of the educational curriculum in an accurate way in order for Kiddo to be a well-grounded teaching support tool with a solid objective.

3.4. Game Learning Analytics Data Collection

One of the most important features offered by the game framework, uAdventure, is the easy configuration for the collection of analytics, which allows us to track the interactions of players with the game. Converting these traces into useful information is of utmost importance to better understand the player experience. The objective of these analytics in Kiddo is to consolidate the process of analyzing relevant information during gameplay and finally use these data to help in the game validation process.

Learning analytics rely on big data trends, in which most interactions are traced and then queried and analyzed to extract value from them. The format used in uAdventure to collect learning analytics data is called Experience API (xAPI). In Kiddo, there is only one player from whom all these traces generated through the interactions between chapters, characters, and objects will be taken. The xAPI traces are collected following a JSON format using an xAPI-specific scheme, and uAdventure offers CSV conversion support for easier analysis. The user guide, the installation guide, and the detailed manuals of the uAdventure features and capabilities can be found on GitHub (https://github.com/e-ucm/uAdventure (accessed on 23 February 2023)).

The traces specifically collected in Kiddo include the start of the game, the start of each chapter, the interaction with the game objects, the access to the fight scene with the monster, the access to the educational video, the end of each chapter, and finally the end of the game. All such traces contain the consequent timestamps.

3.5. Tools and Statistics

The data definition, collection, and initial analysis were performed using uAdventure, Xasu (xAPI Analytics Supplier Ver. V103, last updated in Uadventure on 27 October 2022), and Simva (Simple Validator), tools developed by the e-UCM Research Group that allow a clear tracking of the traces and information generated by Kiddo. Particularly, uAdventure was in charge of the analytics data collection, using Xasu to send its results to Simva, which also gathered the results from the questionnaires.

All collected data were aggregated and revised by the lead researcher. The analysis of the collected data was performed by a researcher from e-UCM and revised by two other researchers from the group with extensive data analysis experience in descriptive statistics. Spreadsheet software was used to aggregate the data and obtain basic statistics. Statistical coding was used for a complete information exploitation process. Open-ended responses were analyzed individually to manually group them according to their content, given the limited number of responses.

The source code of all these tools has been published as free software and can be found on the e-UCM Research Group GitHub page, including documentation and other useful resources such as manuals and free assets (https://github.com/e-ucm (accessed on 23 February 2023)).

4. Initial Usability and Acceptance Evaluation

4.1. Methods

The evaluation carried out on the first chapter of Kiddo had a twofold purpose: (1) to evaluate the usability of the game and (2) to evaluate the acceptance of the game, using its first chapter as a test pilot.

- I.

- Usability evaluation

The usability evaluation conducted for Kiddo was based on usability surveys conducted periodically by commercial videogame companies (in this case, by Garena, known for its star title “Free Fire”, a commercial battle royale videogame with millions of users across the globe). In the surveys, users are asked about their operating systems, the devices they use to play the game, the devices they have access to, etc. These questions are highly relevant to Kiddo’s usability evaluation and proved to provide highly important information. The final questionnaire used for the usability evaluation was adapted from the abovementioned surveys [20], selecting the questions that were relevant to the Kiddo content. The questionnaire started with some basic questions about the game environment (which device and operating system did the users play the game on and which device they preferred to play on) and whether they had any issues installing or executing Kiddo, with an optional open-text field to describe any issues encountered. After that, the usability questionnaire included 13 free-text questions (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Questions included in Kiddo’s usability questionnaire.

- II.

- Acceptance evaluation

The questionnaire used to evaluate the game acceptance was based on the one used in “Campus Craft” [21], adapted to the context of Kiddo’s topics and addressing questions especially designed to evaluate the general acceptance of the pilot game. It contained three parts: (1) demographic information about participants, (2) acceptance of the characters in the game, and (3) acceptance of the game story.

The demographic information inquired about age, gender, and profession.

The characters’ acceptance questions included five questions about their opinion about the game characters, with three possible answers (“fun”, “boring”, and “I don’t care”), and two further five-point Likert questions about the style of the characters.

The story’s acceptance questions included: four five-point Likert questions inquiring about participants’ opinions about the speed of the game texts, how fun the story was, how likely they are to play new chapters of the game, and if they consider the gender equality message of the game to be clearly depicted; a set of seventeen tags (killing time; educational; simulation; leisure; social; bored; teamwork; adventure; easy to play; understandable; good control, comfortable to handle; intuitive; low demands on my computer/is light/works well on my computer; irrelevant; interesting; uninteresting; difficult) from which the user is asked to choose the three that they consider to best describe Kiddo; a score (1 to 10) of how much they liked the pilot chapter; and two final free-text questions about anything that they would add/erase from the chapter and final comments/suggestions for the game.

- III.

- Participants

The first prototype of Kiddo, including chapter 1, was played by 10 participants, between 20 and 51 years old, of different professions related to education and social studies (a social science student, two high school students, a nurse, a sociologist, a consultant, an administrative assistant, two primary education teachers, and a school supervisor) from Mexico.

- IV.

- Evaluations

These initial evaluations began on 15 September 2022, and lasted for 22 days, ending on 7 October 2022. The evaluation was performed from the participants’ homes with their own technological devices (laptops, PCs, smartphones, or tablets) in Mexico. A video tutorial was sent to the participants, along with the proper APKs and EXEs, to help them with the installation of the game, avoid any issues, and ensure a clean install. However, for older users (50+), the intervention of the developer via videoconference or a phone call was needed since they were not too familiar with the installation process. After playing the first chapter of the game, participants provided their opinion using online forms. Their comments and improvements suggested by the test users were used to modify and improve Kiddo and produce the next version of the game.

4.2. Results of Initial Usability Evaluation

Kiddo prototype executables were created and provided for participants for both Android and Windows. Regarding the participants’ regular usage of videogames, two participants declared playing more than four hours a day, three participants played between one and three hours a day, two participants rarely played videogames, and the other three did not play videogames at all. In terms of their playing devices, one participant preferred to play on a console, another participant on a tablet, four on smartphones, and the other four preferred to play on a laptop or PC. Three participants played Kiddo on PCs, one on a tablet, and the other six on smartphones.

During the game’s installation on a PC/laptop, some participants experienced problems because their PCs were too slow and/or the screen froze. During its installation on a smartphone, some participants experienced problems because they did not understand the installation instructions and were not able to install the game on smartphones so they changed to PC, where they were able to successfully install and play Kiddo. Overall, four participants successfully installed Kiddo without any issues, while three participants stated that they encountered some issues during the installation of the game. In general, participants under the age of 40 were able to install Kiddo on their devices, and those over 40 required some more specific guidance to complete the installation of the executable on the desired device.

Table 3 shows the summary of the responses for the usability questions (stated in Table 2). The results show positive outcomes in game completion (question 12), scene changes (question 9), and interactions with characters and items (questions 1 and 2). The most important errors appeared at the start of the game, where participants were not sure about what they had to do (question 9), the instructions did not help them (question 5), and some issues with the game interface arose, such as finding the buttons (question 6).

Table 3.

Results of Kiddo’s usability questionnaire.

4.3. Results of Initial Acceptance Evaluation

The participants provided several insights in the first part of the acceptance questionnaire. Regarding the characters, María (girl) and Juan (boy), most participants thought that the characters were funny and they liked the style of the twins. Regarding the parents’ characters (Lucy and Roberto), most participants did not show any interest in the appearance of the parents nor were they attracted to the style of the parents. Regarding the speed of the texts, most participants thought that the speed of the texts was too slow. Regarding the new chapters, all participants said that they were interested in playing a new chapter of the game. Regarding the story, most participants thought that the story was funny/interesting enough. Finally, regarding the message of the game, all participants stated that the message of gender equality was clear.

Regarding the list of keywords provided, in which participants selected the three words that they believe best describe Kiddo, the main results were as follows: all participants selected “educational”; several participants selected the keywords “simulation”, “social”, and “understandable”; and some participants selected “low demands on my computer/is light/works well on my computer”, “good control, comfortable to handle”, “adventure”, “intuitive”, “easy to play”, and “interesting”. It is noticeable that no participant selected any of the negative keywords (“bored”, “irrelevant”, “uninteresting”, or “difficult”). The average rating for the overall score given by participants for the first chapter (pilot) of Kiddo (on scale of 1 to 10) was 7.5.

The participants provided some suggestions or areas of opportunity to improve the chapter, including possible additions to the game (e.g., more precise indications, a help button, and an initial video to set up the story) and changes (e.g., shorten some of the dialogues). The final free comment section allowed for additional suggestions to improve the next chapters of Kiddo. Participants’ comments included:

- “I suggest creating and fighting the stereotypical monster of fear of decision making, it would be worthwhile to add to autonomy training”.

- “I liked the characters in general, but the monster is more attractive than the rest”.

- “Testing with children, as an adult you may not understand a lot of things, but children are more likely to find their way around faster”.

- “Add instructions and improve the style of the parent characters”.

- “The hearts representing the health or the life of the character, are really confusing. I thought that those were the Hearts of Courage, but they were life indicators”.

- “It is a very interesting proposal to present cases where analysis and decision making are encouraged. The design can be made more attractive, and the activities and challenges of the game can be related in a more direct way”.

- “I found the message of respect in terms of choice of tastes and gender interesting, but the story gets long with the dialogues, it would be good to include an introduction and instructions on how to play and at the end of the chapter a brief conclusion”.

5. Formative Evaluation with Teachers

5.1. Methods

Using the prototype containing the first three chapters of Kiddo, we conducted a formative evaluation with teachers to ensure that they considered the game a useful educational tool to use in their classes and to gather their opinion on whichever change they considered useful to include in the game. Additionally, the comments and suggestions made by teachers are addressed in the game’s teacher guide. This teacher guide is provided along with the game to simplify its application in classes after the game is completed and validated.

- I.

- Questionnaires

The questionnaire presented below was designed to facilitate the identification and measurement of sexist behaviors among school-aged children. The questionnaire was created by combining and adapting three main studies: a Mexican study and its main questionnaire, the EVAMVE scale, and a UNICEF guide.

The first instrument is the questionnaire included as part of a study to make visible the stereotypes and gender violence situations faced by boys and girls in Mexico. This questionnaire was applied to a sample of more than 26,000 primary school students in Mexico in 2009, including different gender stereotypes, with which students were asked to state how much they agreed or disagreed.

The second instrument is the EVAMVE scale, a questionnaire used to measure sexist attitudes, violence, and stereotypes in adolescents, developed by health professionals from different educational institutions in 2018 [22]. The scale was validated with a sample of 283 high school students using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The final scale demonstrated reliability in the results, which were submitted to a panel of experts from various disciplines for their consideration. The EVAMVE scale items were adapted for their application to primary school students and added to the final Kiddo questions.

The third instrument is a guide for mothers, fathers, guardians, and teachers to confront gender stereotypes and promote equal treatment among boys, girls, and adolescents, called “Growing up in equality” and published in 2019 by UNICEF, which presents a list of 11 stereotypes [23]. As these are examples presented by UNICEF in a more recent context (2019), these stereotypes represent the current trend while reaffirming the stereotypes presented by Azaola Garrido in 2009, since even with 10 years of difference, the stereotypes are repeated on many occasions in both studies.

All three questionnaires were analyzed, and the questions that were relevant for the current study were included and adapted to the language of the participants. Particularly, statements related to gender stereotypes that are not addressed in the game Kiddo were omitted from the questionnaires. Those questions that constitute an instrument to measure gender stereotypes are used in the questionnaires. The higher the score obtained on the stereotype scale, the more likely it indicates a tendency towards sexist behavior. This evaluation followed the pre–post testing scheme, where the questionnaire is answered before and after the experiment to later compare the responses, and therefore, two versions of the questionnaire were defined.

The pre-test contained four sections: a first section with a privacy statement indicating the conditions of data collection; a second section used to collect the general data of the player, such as age, school grade, and sex (see Appendix A); a third section comprising four diagnostic statements of sexist behavior, which must be answered by using a five-point Likert scale so that the data obtained can be subsequently analyzed (see Appendix B); and a final section containing 16 statements on gender stereotypes (the instrument used to measure gender stereotypes), related to the four chapters of Kiddo, which should be answered using again the five-point Likert scale (see Appendix C).

The post-test included both the same diagnostic statements and gender stereotypes (Section 3 and Section 4 of the pre-test) for comparison (see Appendix B and Appendix C). Additionally, it included eight statements regarding user experience with the game (see Appendix D) to be answered again using a five-point Likert scale and eight additional open-text questions about the participant’s opinion regarding the game, problems encountered, and applicability of the game in classes (see Appendix E). Specifically, the eight questions are

- Have you managed to complete the game?

- Did you have any problems during the game?

- What did you like most about the videogame Kiddo?

- What did you not like about the videogame Kiddo and what would you change to improve it?

- What do you think of the story, do you find it interesting, funny, or appropriate?

- What has the game made you think about?

- What would you like to see us add or remove in the following chapters to improve the story?

- Can this game be used in the classroom, and how would you apply it?

All data collected are anonymous and do not enable the player to be identified in any way. The experiment consisted of three parts: (1) answering the pre-test, (2) playing the Kiddo videogame, and (3) answering the post-test. After that, we compared the answers between the pre- and post-tests for the gender stereotypes instrument. The expected scenario was to obtain a reduced score in the post-test compared to the pre-test, which would indicate that Kiddo would have managed to clearly deliver an educational message on equality. The maximum score, which would indicate an overall inclination towards sexist behaviors and the perpetuation of stereotypes, was 80 points, while the minimum score, which would indicate a total absence of sexist behaviors and stereotypes, was 16 points. The average score was 48 points and would indicate a neutral attitude towards the problems presented.

- II.

- Participants

For the teacher´s test stage, we used a collective invitation to Mexico City´s teachers; the only requirement was for the participant to be an elementary school teacher, regardless of the shift or school to which they were assigned.

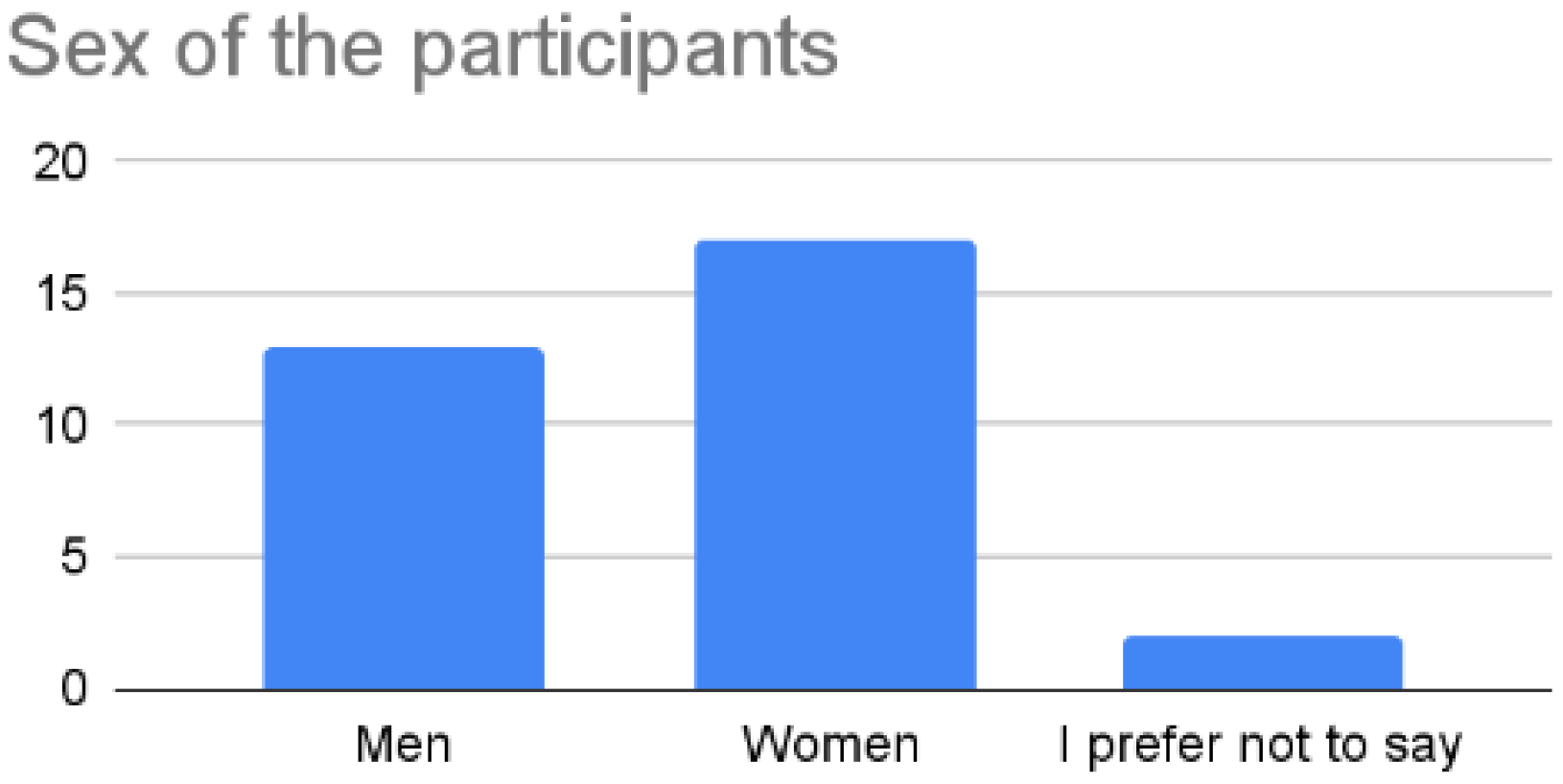

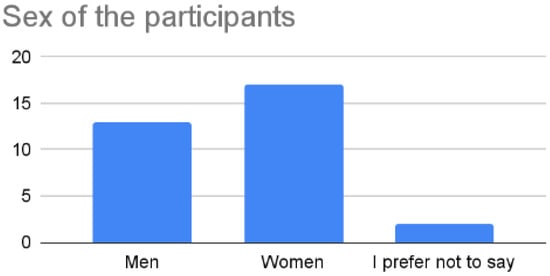

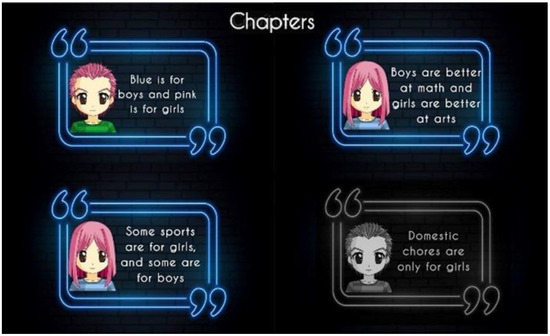

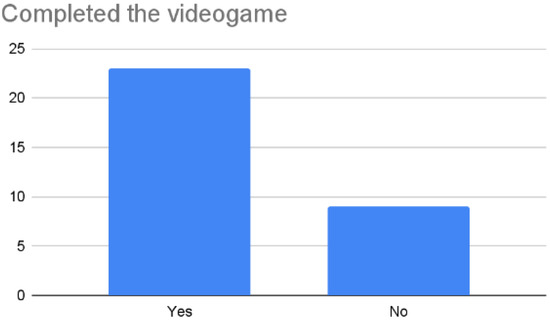

After discarding some teachers’ participation due to time issues, teachers’ personal issues, not being primary teachers, etc., the final number of participating teachers was a total of 32, all of them teaching in elementary schools in Mexico City. Of the 32 participants, 18 were women, 12 were men, and 2 preferred not to give their gender (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sex of participants in Kiddo’s formative evaluation with teachers.

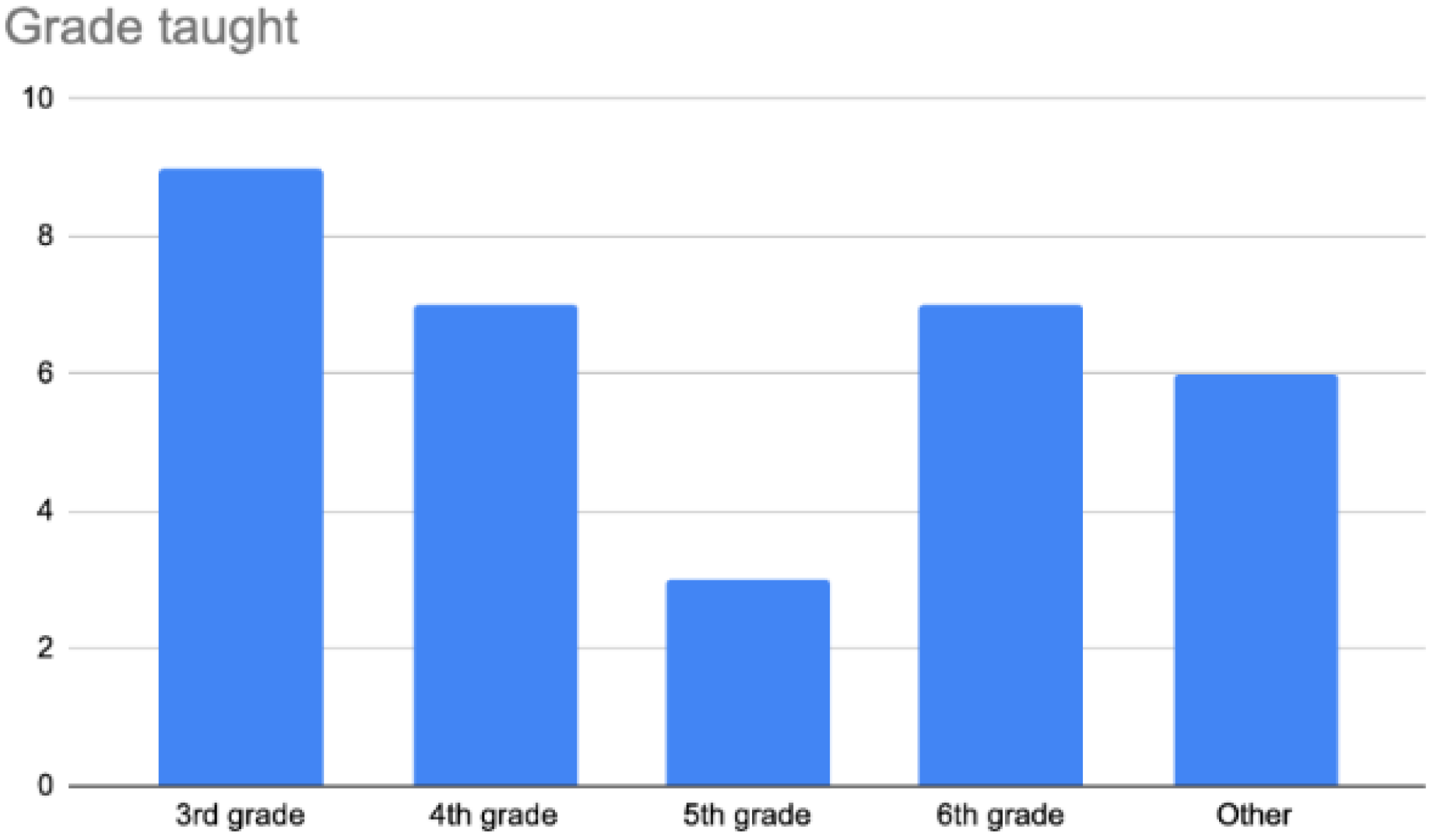

The participating teachers were asked the grade in which they teach, and we obtained the following information: nine were third-grade teachers, seven were fourth-grade teachers, three were fifth-grade teachers, seven were sixth-grade teachers, and six were teachers of other grades or specific disciplines (including physical education, computing, first grade, and second grade) (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Course taught by teachers participating in Kiddo’s formative evaluation.

Kiddo is intended to be applied from third grade onwards. However, when it is released in 2023, it will not be recommended for the third grade. According to the feedback received by the “Dirección de Educación Primaria”, the grades in which Kiddo should be applied are from fourth grade onwards. This is due to the educational backwardness of some third-grade students after the COVID-19 pandemic, since some schools were closed or provided a very limited distance education for more than one year, causing slower progress for students than expected.

Regarding the participants’ age, most participants (28) belonged to the age range of 21 to 40 years, while only four participants were older than 41 years old (up to 60 years old). This gives us an average age of 32.75 years. During the experiments, the four older people expressed their difficulties with some parts of the evaluation (“I don’t know how to use the computer” and “I have never played a videogame”), so they were given a little more personal accompaniment while playing the game.

- III.

- Evaluation

The evaluation of the game comprised three chapters and included the corrections and suggestions of the first chapter, as well as the recommendations of the school authorities (“Dirección de Educación Primaria”). It also included pre-test and post-test evaluation questionnaires.

To perform this evaluation, the Kiddo project adhered to the suggestions made by the academic authorities and focused on the utilization of the third-grade textbook titled “Civic and Ethical Formation” [24] to match Kiddo’s content to the approach presented in the book. In the book, in Block 2, Sequence 3—the theme Building Equality Together, we were able to find the three fundamental pillars relevant to supporting the development of chapters 2 and 3 of Kiddo:

- “Girls and boys have the same rights and should have the same opportunities for their development”.

- “The social roles of women and men”.

- “Actions that favor equal treatment between girls and boys at school”.

- Once the development was completed, an invitation was launched so that interested teachers could participate in the evaluation.

The Kiddo project evaluation with teachers in Mexico City was carried out in February and March 2023.

The implementation of the Kiddo project was possible thanks to the support of a public elementary school, which provided access to its computer classroom, allowing the evaluation to be carried out smoothly.

The computer room had 30 computers, 23 with a 32-bit Windows system and 7 with 64-bit Windows. Older computers required a special 32-bit executable file; however, the speed of the computers’ processors was too slow, and it was not feasible to use these computers, so the game was applied to groups of seven teachers in a five-hour period. After two days of evaluation at the school, a total of 32 teachers completed the three activities (pre-test, gameplay, post-test).

The chapters and topics available for the evaluation were the following: about colors, “Blue is for boys and pink is for girls”; about education, “Boys are better at mathematics and girls are better at arts”; and finally about physical activities, “Some sports are for girls and others for boys”. The menu displayed for the evaluation and the available chapters were shown in bright blue, while the last chapter was locked and displayed in gray because it was still under development (see Figure 8). Teachers were able to choose between the chapters “Blue is for boys and pink is for girls” and “Some sports are for girls and others for boys” to start the game since the chapter that constitutes the end of the game is “Boys are better at mathematics and girls are better at arts”.

Figure 8.

Chapters of Kiddo available in teacher evaluation.

During this application process, the participants were told the order in which it was suggested to play; however, when they ignored the indication and since there were no visual indicators in the game to guide them, some participants only managed to play the final chapter. Figure 9 shows some pictures taken during the two different days of the teacher evaluation of Kiddo.

Figure 9.

Pictures taken during the formative evaluation with teachers.

5.2. Results of Formative Evaluation with Teachers

A total of 32 teachers completed the three activities (pre-test, gameplay, post-test) within the two days of the evaluation. The first day of the evaluation was successfully completed by a total of 24 participants within 28 min.

The second day of the evaluation was completed by eight participants. However, due to a failure of the internet connection, the post-test could not be completed within the game so it had to be filled out manually on paper and later introduced into the survey management system using the participants’ unique IDs. The average time of the application was 35 min.

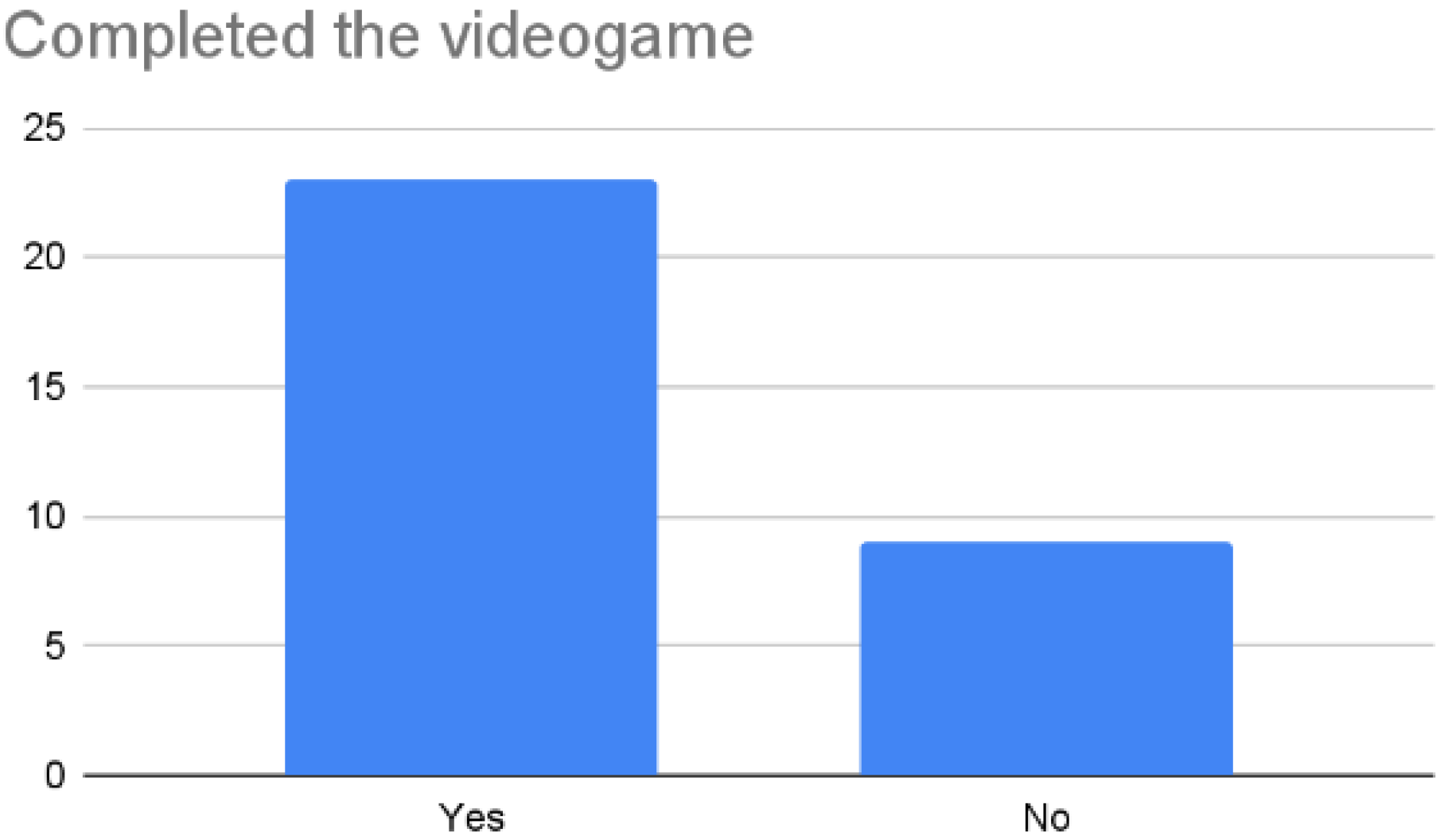

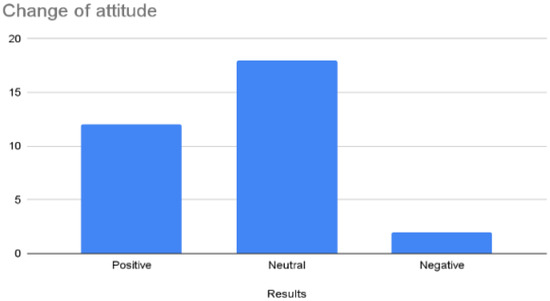

Regarding the gameplay results, twenty-three participants managed to complete the game and nine participants did not reach the end of the videogame, and the reasons why they did not manage to complete it were successfully identified (see Figure 10). For those who did not complete the game, the reasons were that the second chapter experienced a bug that caused the game to suddenly close, thus skipping chapter 3 (four participants); the computer equipment failed to process the graphics, causing the image to freeze at some unpredictable moment during the gameplay (two participants); and the lack of an internet connection (three participants).

Figure 10.

Kiddo’s completion in formative evaluation with teachers.

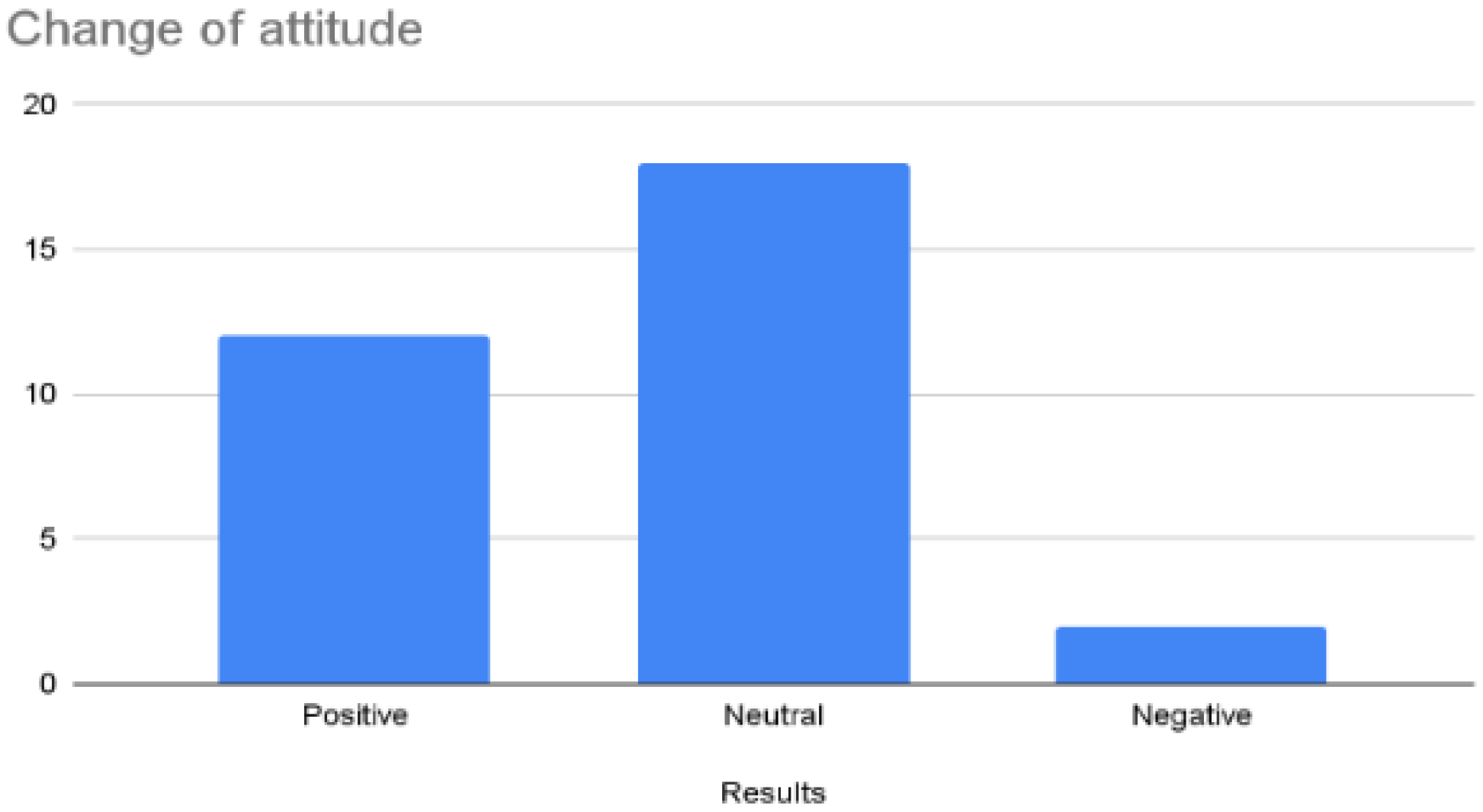

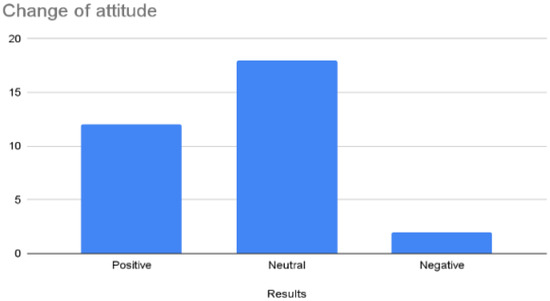

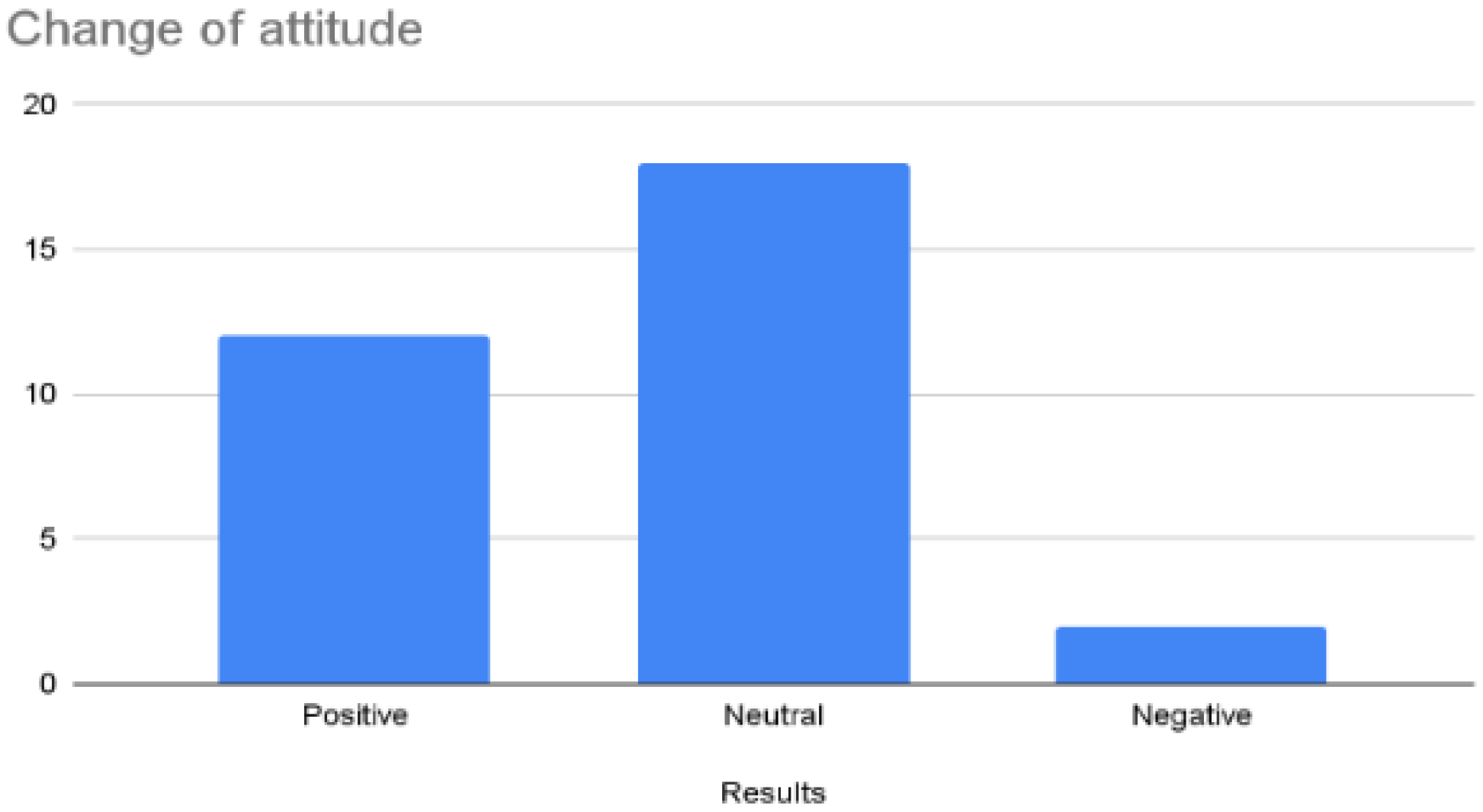

The results of the attitude changes between the pre-test and post-test were divided into three groups and are as follows (see Figure 11):

- The Neutral group maintained their attitude towards equality. Generally, participants in this group were already showing a positive attitude towards gender equality.

- The Positive group had a positive attitude change towards equality. This group showed a sexist stereotype-oriented attitude in the pre-test and a decreased sexist attitude in the post-test.

- The Negative group had a negative attitude change. In this group, participants showed a positive attitude in the pre-test but had an increased sexist attitude after playing the game. We had a couple of outlier cases in which different situations (reading errors, errors in writing on sheets of paper, or problems in understanding the questions) could have affected the results.

These results only show an indication of the effect of the game, as the participants in this case were not part of the game’s target group.

Figure 11.

Results of comparison between the pre-test and post-test in Kiddo’s formative evaluation with teachers. Each bar displays the number of participants that belong to the group.

Figure 11.

Results of comparison between the pre-test and post-test in Kiddo’s formative evaluation with teachers. Each bar displays the number of participants that belong to the group.

The sections that were compared during the pre-test and post-test are divided into diagnostic statements of sexist behaviors (four statements) and statements about stereotypes (four blocks of four statements).

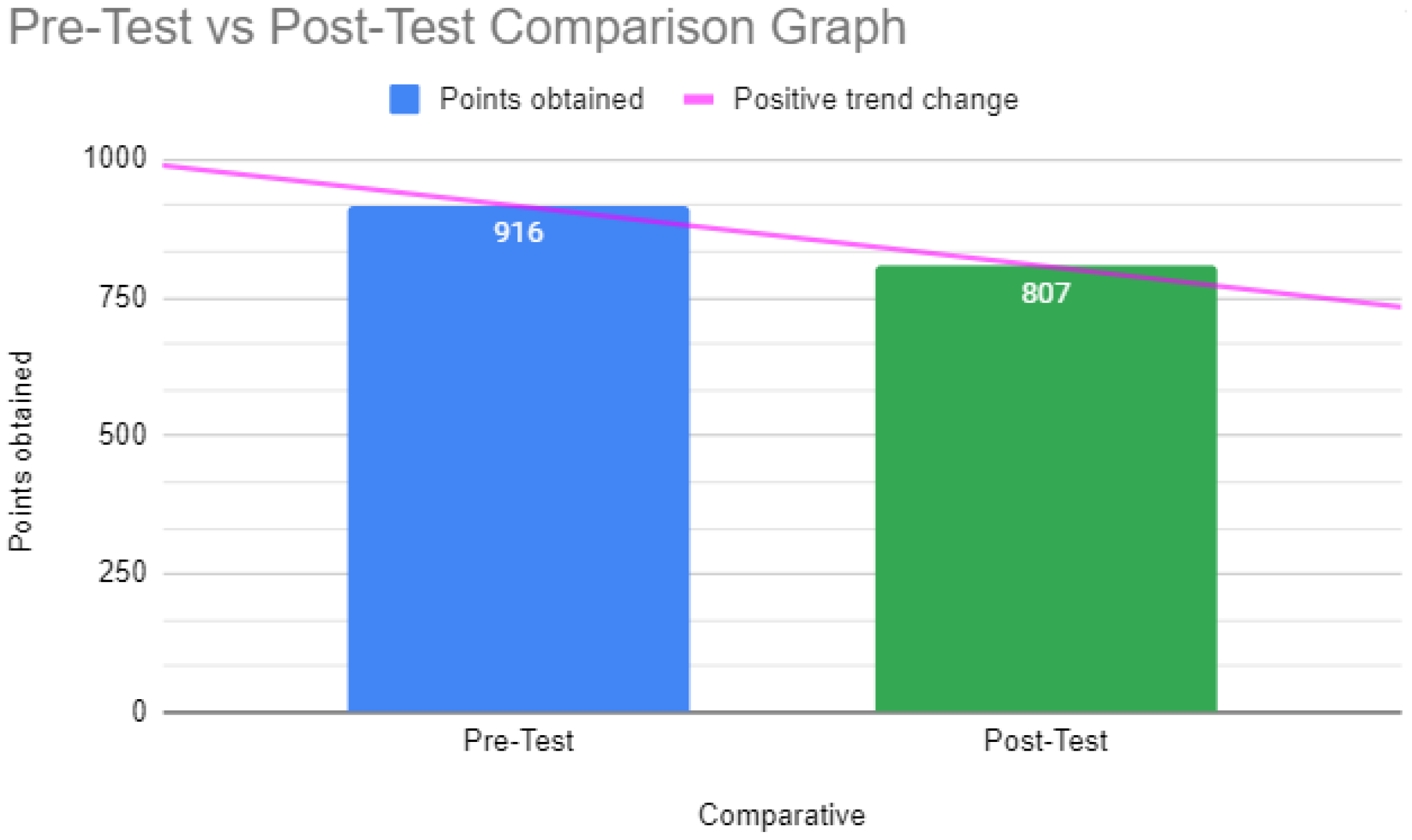

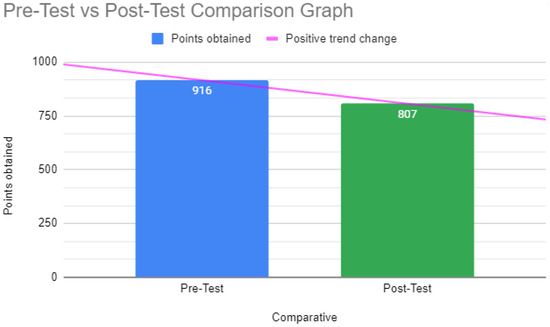

Returning to the point system adopted in Section 5.1. (Methods, Questionaries), the total number of points in a group of 32 people with a sexist attitude would be 2560 points; on the other hand, in the same group of 32 people with a non-sexist attitude, the score would be 512 points.

In the formative evaluation with teachers, during the pre-test, the players obtained a total of 916 points. Once the teachers played the videogame and answered the post-test, they obtained a total of 807 points, showing that sexist behavior decreased by a total of 109 points, resulting in a positive change, i.e., sexist behaviors tended to decrease after playing the videogame Kiddo (see Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Trend comparing pre-test and post-test results when playing Kiddo.

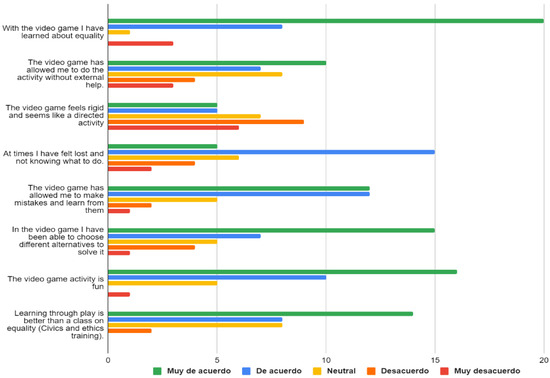

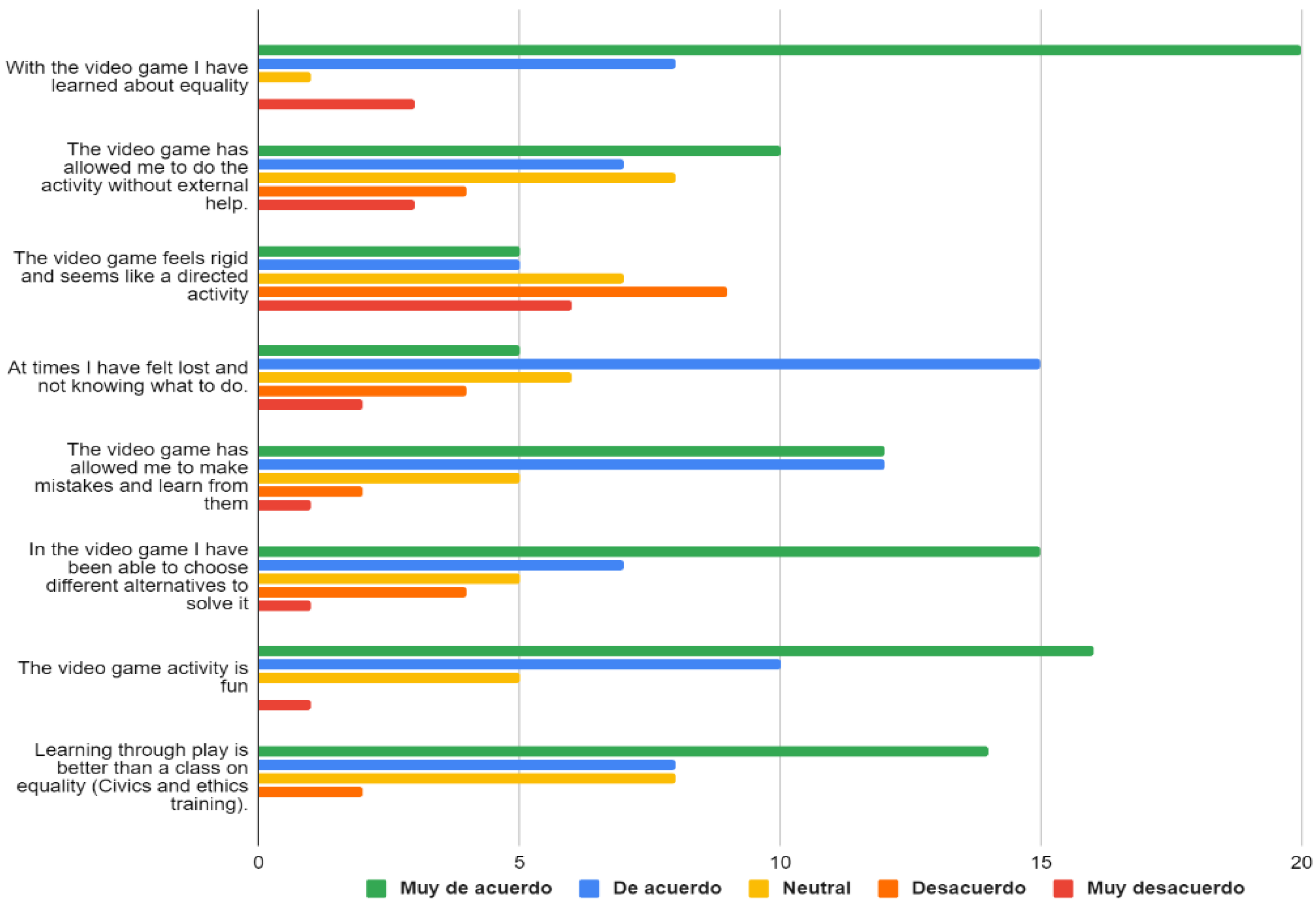

Regarding the participants’ comments and opinions about Kiddo, we have two sections: the first is a series of eight statements rated using a five-point Likert scale (see Figure 13), and the second corresponds to eight open questions.

First section (Likert answers)

- “With the game I have learned about equality”: Most of the participants stated that with the videogame, they have learned about equality.

- “The game has allowed me to do the activity without external help”: Most of the participants managed to finish the videogame without help; meanwhile, a few older participants required a preliminary explanation of how to play the videogame and how to use the computer.

- “The game feels rigid and seems like a directed activity”: Most of the participants felt that the activity is friendly, i.e., not rigid.

- “At times I felt lost and not knowing what to do”: Most of the participants felt lost at some point in the videogame.

- “The videogame has allowed me to make mistakes and learn from them”: Most participants felt that during the game, when they made mistakes, they were able to learn from them in order to not repeat them and to finish each chapter of the videogame.

- “In the videogame I have been able to choose different alternatives to solve it”: Most of the participants mentioned that they had different alternatives to solving the videogame and followed their own decisions.

- “Videogame activity is fun”: Most of the participants mentioned that the activity was fun.

- “Learning with a videogame is better than an equality class (civic and ethical training)”: Most of the participants mentioned that they totally agree with the phrase “learning with a videogame is better than an equality class”.

Figure 13.

Results for the 8 user experience statements.

Figure 13.

Results for the 8 user experience statements.

Second section (open text questions)

In the question regarding what they liked the most about the videogame Kiddo, most participants stated that they liked the characters (“including the monsters”), the interactions with them, and the fact that the videogame allows one to adopt different supportive roles with the characters. A teacher stated that: “I consider that the theme can contribute to address stereotypes, hypersexualization and conservative conceptions that cause to a certain extent, discrimination, rejection and isolation”.

Regarding the story, most of the participants mentioned that it addresses a very present topic in an appropriate, fun, and interesting way. Teachers also stated that the game seemed appropriate, particularly for the “level of language and maturity of the students”.

On whether Kiddo has made them reflect, most of the participants stated they feel like reflecting about the messages delivered by the videogame; they also specified that they reflected on equality, gender roles, stereotypes, and taboos.

As for what they would like to add or remove to improve the story, almost all participants mentioned that they would like more chapters and scenarios to be added as well as accessibility improvements such as voiceovers.

Regarding the possible use of this game in their classes, all participants mentioned that they did feel that they could use the game in civics and ethics classes. One prominent comment was: “Yes, for students who do not allow girls to play roles (in the classroom, in the playground, etc.) that they think are only male student’s roles”.

The most common problems encountered by the participants during the game were the fact that the game froze for a few moments, as well as Internet connection errors.

Finally, regarding possible improvements in Kiddo, a significant number of participants requested removing the internet connection requirement. In addition, they would have liked an option in the menu to go back to the menu and play again.

6. Discussion

6.1. Usability and Acceptance Evaluation

The results of the usability evaluation and the acceptance evaluation of the first Kiddo prototype are very promising. The initial evaluation carried out for its first pilot chapter received mainly positive feedback from the participants, which leads us to expect a good acceptance among the final users. The current evaluation shows that Kiddo still needs some work to be completely accessible for all users. Particularly, the beginning of the game was not clear enough, and additional instructions need to be provided to players to help them to understand the purpose of the game. The game should include a better tutorial to guide players in their initial interactions with the game and to clearly state the game goal. Although we know that there are some issues with the pilot version of Kiddo, the comments and suggestions gathered from this evaluation allow us to address these found issues and get them fixed in the final version of the game.

6.2. Formative Evaluation with Teachers

The formative evaluation of Kiddo with teachers provided valuable comments. Most of the teachers participating in the evaluation of the videogame thought that it was a support tool that could be used in class, as it is aligned with the Secretary of Public Education book, such as the one contained in Block 2, Sequence 3 (Building Equality Together) of the Civic and Ethical Formation book for the third grade, which of course promotes confidence in teachers and encourages them to use the videogame as a practical part of the academic load. Of the 32 participants, 30 said they could use it in the classroom and 2 said they could “maybe” use it in the classroom, one of whom clearly stated “maybe if there is an internet connection”.

Kiddo represents the reality that thousands of girls and boys in Mexico live day by day, and the results of the formative evaluation were quite positive. Among the comments obtained in the post-test, we can highlight the following: “I believe that in Mexico we still have a long way to go regarding gender issues. This is a great approach” and “It is a good game for the students, since there are several stereotypes present”.

Regarding Kiddo’s improvements, the participants hoped that “more chapters will be included”, “more decisions can be made”, and “more activities can be added” and among them, this comment stands out “That the characters (comics) talk”. This last comment is aimed at being able to use the game with younger children.

As for the teachers’ concerns, some wanted to be able to take the videogame home so they could use it with their own family members, and others asked about where they could play it and if it could be played on their smartphone.

During the application of the game, it was possible to identify the feeling of frustration while playing chapter 2, which corresponds to the sports stereotype; in this chapter, we found that some participants, mostly of the female sex, were extremely frustrated when the decisions made Maria feel sad. This is a clear example of the empathy that is generated between the character and the player.

6.3. Limitations

The results of the Kiddo project evaluation showed several important limitations that can be divided into three groups: technical limitations, logistical limitations, and administrative limitations.

Technical limitations. Two of the most important problems encountered during the two evaluations were problems during the installation of the videogame on old computers, as well as the need to create versions of the game for 32 and 64 bits. On the other hand, depending on public internet connections caused disconnections and an intermittent Internet signal.

Logistical limitations. During the deployment of the evaluation with teachers, several problems were encountered. First, computer equipment caused problems. It is important to highlight that many of the public elementary schools in Mexico do not have updated or functioning computer labs. There are cases in which computer laboratories and equipment are no longer used due to a lack of maintenance or to prevent computer parts being stolen. Some other computer rooms had computer equipment that was donated by governmental administrations and contained administrative protection that blocked the installation and execution of the games. Second, the internet connection caused problems. Public schools in Mexico do not normally have their own internet connections; however, there are schools that are within the range of public internet connection points in Mexico City, which enables the use of a public internet connection. However, these connections are not reliable as they only allow a certain connection time (usually 60 min) and have a certain limit to the number of connections, which caused a loss of connection during the videogame evaluations in some cases. All these limitations complicate the possibility of applying the videogame in many public schools.

Administrative limitations. A major limitation for the Kiddo project is the requirement of the approval of the educational authorities for its implementation in public schools with minors. To obtain this approval, it is indispensable that Kiddo be aligned with the academic plan of Civic and Ethical Education so that it can complement and expand the education for equality already contained in the programs of the Secretary of Public Education. An example of this content is found in the book “Civic and Ethical Formation for third grade”, Block 2, Sequence 3 (Building Equality Together), edited by the Ministry of Public Education, whose content was adapted during the development of Kiddo so as to align it with the issues of interest to the Ministry of Public Education.

7. Conclusions

Kiddo is a videogame used to address gender stereotypes in Mexico. The first prototype of the videogame has been evaluated with educators. Although children will be the final players of the game, technical and expert opinions, including those of teachers and gender experts, have helped to identify the issues and areas for improvement in the game. Since the final application of the game in classes will be controlled by teachers, a major focus in this study is that they approve the game and see it as a useful tool to apply in their classes to start a conversation about gender stereotypes.

The main outcome of this evaluation is that the game was very positively perceived by educators as they consider that it could serve as relevant content to initiate a fruitful discussion with the students based on a common experience. They consider that the game could be an effective way to address the topic of gender stereotypes at school.

In this paper, we have presented the results obtained during the evaluation process of the Kiddo project as a complementary tool to make gender stereotypes visible and raise awareness about them. The game has been evaluated throughout its development with the aim of obtaining a quality educational tool that can be used in the classroom as a support for teachers. The evaluations and feedback received were taken into consideration since the beginning of the project, resulting in a more accurate game for the target population: boys and girls from 9 to 13 years old. Since it is aimed at such a young audience, and in order to obtain a didactic tool, all of the content has been validated by experts in primary education.

The results of the evaluation of Kiddo have made it clear that users perceive the videogame as a useful and helpful tool to raise awareness of the gender stereotypes that girls and boys face on a daily basis and that can be effectively applied in the classroom from the fourth grade onwards. Although the application of Kiddo among large groups of students can present a significant challenge, the tests carried out have shown that as long as the appropriate technical and logistical conditions are in place, the videogame is effective and fulfills its purpose of raising awareness.

Among the limitations of the study, and returning to the technical and logistical issues, it is important to mention that technological resources are a factor that can negatively affect the acceptance of this videogame. Although they are external factors and are mostly out of our control, they affect the user experience and may even discourage the user from continuing to participate. If there is a considerable limitation, it can be overcome by using the researcher’s own resources (tablets, laptops, cell phones, etc.) if those found on the application site are insufficient.

The immediate future of Kiddo, once the pertinent modifications derived from the feedback received have been made, is its application in classrooms, in a real educational environment, and collecting the responses and comments of the final target audience (girls and boys from 9 to 13 years old). Later on, and once its effectiveness among girls and boys has been demonstrated, the videogame will be publicly released on GitHub so that it will be available to the general public in its two available versions (Windows and Android) along with its manual and teacher guidelines.

The current version of Kiddo is still a prototype that has been formatively evaluated with a limited number of users. With all the feedback collected from educators and students, we will produce the final complete version of the game. This final version will be applied in at least two elementary schools in Mexico (which have already agreed to use Kiddo in their classes). In these applications, game learning analytics will be collected from players’ interactions with Kiddo. These collected analytics will help us to continue the summative validation of the game and measure the impact of the game on its target players.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.G.B.Y.; Methodology: A.G.B.Y. and C.A.-F.; Software: A.G.B.Y. and V.M.P.-C.; Validation: B.F.-M. and C.A.-F.; Formal analysis: A.G.B.Y. and C.A.-F.; Investigation: A.G.B.Y., B.F.-M. and C.A.-F.; Resources: B.F.-M. and V.M.P.-C.; Data curation: A.G.B.Y. and C.A.-F.; Writing—original draft preparation: A.G.B.Y.; Writing—review and editing A.G.B.Y., B.F.-M., C.A.-F. and V.M.P.-C.; Visualization: A.G.B.Y.; Supervision: B.F.-M. and C.A.-F.; Project administration: B.F.-M. and C.A.-F.; Funding acquisition: A.G.B.Y. and B.F.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the Regional Government of Madrid (eMadrid S2018/TCS4307, co-funded by the European Structural Funds FSE and FEDER), by the Ministry of Education (PID2020-119620RB-I00), and by a student grant from Fundación Carolina.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived due to the lack of access and collection of personally identifiable information or sensitive data from the users/participants of this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons (anonymized data).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Demographic Data |

| How old are you? Numeric field (2 digits) |

| What is the school grade you are teaching? Third grade Fourth grade Fifth grade teachers, Sixth grade teachers, Other grades or specific disciplines |

| What is your sex? Female Male I’d rather not answer |

Appendix B

| Diagnostic Statements of Sexist Behavior |

| The man is in charge at home El hombre es el que manda en casa Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Women should always obey men Las mujeres siempre deben obedecer a los hombres Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Men work, women stay at home El hombre trabaja, la mujer se queda en casa Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| The woman is the one who should take care of the family La mujer es la que debe cuidar de la familia Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

Appendix C

| Statements on Gender Stereotypes |

| There are special colors for girls and unique colors for boys. Hay colores especiales para niñas y colores únicos para niños Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Blue color is for boys and pink color for girls. El color azul es para los niños y el color rosa para las niñas Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Boys should not cry. Los niños no deben llorar Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| It is not right for boys to play with dolls, because this is a girl’s game. No está bien que los niños jueguen con muñecas, porque este es un juego de niñas Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Girls should not do manly things like rough sports. Las niñas no deben hacer cosas de hombres como los deportes rudos Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Only boys are strong. Solo los niños son fuertes Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Girls are weak and delicate. Las niñas son débiles y delicadas Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Girls should not play rough. Las niñas no deben jugar rudo Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Men should not help with housework at home Los hombres no deben ayudar con las labores domésticas en casa Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Only girls should learn how to do housework Solo las niñas deben aprender a hacer labores domésticas Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Only men can use tools at home Solo los hombres pueden usar herramientas en casa Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Boys can be leaders, but girls should only dream of being mothers. Los niños pueden ser líderes, pero las niñas deben soñar solamente con ser madres Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| It is not important that girls study No es importante que las niñas estudien Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Girls are not good at math Las niñas no son buenas en matemáticas Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Boys should not like art A los niños no debería gustarles el arte Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Boys make better decisions than girls Los niños toman mejores decisiones que las niñas Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

Appendix D

| User Experience |

| Through the game I have learned about equality Con el juego he aprendido sobre igualdad Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| The game allowed me to do the activity without external help. El juego me ha permitido hacer la actividad sin ayuda externa Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| I found it to be a very rigid and directed activity. Me ha parecido una actividad muy rígida y dirigida Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| At times I have felt lost and not knowing what to do. En algunos momentos me he sentido perdido y sin saber qué hacer Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| The game has allowed me to make mistakes and learn from them. El juego me ha permitido cometer errores y aprender de ellos Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| In the game I have been able to choose different alternatives to solve it En el juego he podido elegir distintas alternativas para resolverlo Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Activity with the game is fun La actividad con el juego es divertida Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

| Learning through play is better than a class on equality (Civics and ethics training). Aprender con el juego es mejor que una clase de igualdad (Formación cívica y ética) Totally agree (5), Agree (4), Neither Agree or Disagree (3), Disagree (2), Strongly disagree (1) |

Appendix E

| Opinions |

| 1. Have you managed to complete the game? ¿Has logrado completar el juego? |

| 2. Did you have any problems during the game? ¿Tuviste algún problema durante el juego? |

| 3. What did you like most about the videogame “Kiddo”? ¿Qué es lo que más te ha gustado del videojuego “Kiddo”? |

| 4. What did you not like about the videogame “Kiddo” and what would you change to improve it? ¿Qué no te ha gustado del videojuego “Kiddo” y qué cambiarías para mejorarlo? |

| 5. What do you think of the story, do you find it interesting, funny, or appropriate? ¿Qué opinas de la historia?, ¿te parece interesante, divertida o apropiada? |

| 6. What has the game made you think about? ¿El juego te ha hecho reflexionar? ¿Sobre qué? |

| 7. What would you like to see us add or remove in the following chapters to improve the story? ¿Qué te gustaría que añadiéramos o elimináramos en los siguientes capítulos para mejorar la historia? |

| 8. Can this game be used in the classroom, and how would you apply it? ¿Puede usarse este juego dentro del aula? ¿Cómo lo aplicarías? |

References

- Barrera, A.; Alonso-Fernández, C.; Fernández-Manjón, B. Acceptance evaluation of a serious game to address gender stereotypes in Mexico. In Proceedings of the 7th Annual International Symposium on Emerging Technologies for Education in Conjunction with ICWL 2022 (SETE 2022), Tenerife, Spain, 21–23 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, D.R.; Chen, S.L. Serious Games: Games That Educate, Train, and Inform. Education 2005, 31, 1–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Morata, A.; Alonso-Fernández, C.; Freire, M.; Martínez-Ortiz, I.; Fernández-Manjón, B. Creating awareness on bullying and cyberbullying among young people: Validating the effectiveness and design of the serious game Conectado. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 60, 101568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, A.H.; Bauer, R.; Lienert, J. A review of water-related serious games to specify use in environmental Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2018, 105, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitarch, R.C. An Approach to Digital Game-based Learning: Video-games Principles and Applications in Foreign Language Learning. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2018, 9, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gender Stereotyping. OHCHR and Women’s Human Rights and Gender Equality. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/women/gender-stereotyping (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Hietanen, A.E.; Pick, S. Gender Stereotypes, Sexuality, and Culture in Mexico. In Psychology of Gender through the Lens of Culture; Safdar, S., Kosakowska-Berezecka, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaola, E. Patrones, Estereotipos y Violencia de Género en las Escuelas de Educación Básica en México. La Ventana. Rev. Estud. Género 2009, 4, 7–45. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S1405-94362009000200003&script=sci_abstract (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Denner, J.; Laursen, B.; Dickson, D.; Hartl, A.C. Latino Children’s Math Confidence: The Role of Mothers’ Gender Stereotypes and Involvement Across the Transition to Middle School. J. Early Adolesc. 2018, 38, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Sandhofer, C.M.; Brown, C.S. Gender Biases in Early Number Exposure to Preschool-Aged Children. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 30, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiunas un Videojuego Para Transformar las Relaciones Desiguales Entre Mujeres y Hombres. Available online: https://colombia.unwomen.org/es/noticias-y-eventos/articulos/2018/5/tsiunas (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Jesse—A None in Three Game. Available online: http://www.noneinthree.org/barbados-and-grenada/jesse/ (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- The Island Network for Gender Equality “Tenerife Violeta”, “Berolos”. 2020. Available online: https://www.tenerifevioleta.es/berolos/ (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Instituto Andaluz de la Mujer (Spain), “IGUALA-T”. 2018. Available online: http://www.iguala-t.es/app/login (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Yasmin, B.K. Considering gender in digital games: Implications for serious game designs in the learning sciences. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on International Conference for the Learning Sciences—(ICLS’08), Utrecht, The Netherlands, 23–28 June 2008; International Society of the Learning Sciences: Buffalo, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 422–429. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera Yañez, A.G.; Alonso-Fernandez, C.; Fernandez Manjon, B. Review of serious games to educate on gender equality. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality, Salamanca, Spain, 21–23 October 2020; pp. 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuka. Available online: http://www.chukagame.com/ (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Pérez Colado, V.M.; Pérez Colado, I.J.; Manuel, F.; Martínez-Ortiz, I.; Fernández-Manjón, B. Simplifying the creation of adventure serious games with educational-oriented features. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2019, 22, 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, M.; Serrano-Laguna, Á.; Iglesias, B.M.; Martínez-Ortiz, I.; Moreno-Ger, P.; Fernández-Manjón, B. Game Learning Analytics: Learning Analytics for Serious Games. In Learning, Design, and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garena Free Fire, Usablity/Satisfaction Survey. Available online: https://www.surveycake.com/s/9PVwx (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Jozkowski, K.N.; Ekbia, H.R. “Campus Craft”: A Game for Sexual Assault Prevention in Universities. Games Health J. 2015, 4, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchal Torralbo, A.M.; Brando Garrido, C.; Montes Hidalgo, J.; Tomás Sábado, J. Diseño y validación de un instrumento para medir actitudes machistas, violencia y estereotipos en adolescentes. Metas de Enfermería 2018, 21, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia (UNICEF) Junio. 2019. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/chile/media/3076/file/lacro-igualdad.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Formación Cívica y Ética. Tercer Grado. Primaria. Dirección General de Materiales Educativos. Secretaría de Educación Pública. 2022. Available online: https://libros.conaliteg.gob.mx/2022/P3FCA.htm#page/1 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).