Abstract

Reading literacy has been considered one of the essential vital competencies in modern society and has thus gained increasing attention in research. With both qualitative and quantitative research methods, this study aimed to investigate the overall picture in this research field and investigate the role of reading motivation and online reading activities and how online reading literacy was assessed. The top ten organizations, countries with the highest publications, author keywords, all keywords, cited references, cited sources, and cited authors were visualized via VOSviewer clustering and counting techniques. Reading motivation, online reading activities, and digital reading literacy assessment tests were also explored through the visualization citation network in CitNetExplorer. In conjunction with the citation network, 13 peer-reviewed articles were selected for further analysis based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocol (PRISMA-P). The results show that reading motivation played an essential role in reading literacy achievement in formal schooling, while online reading activities could both positively and negatively affect digital reading literacy due to their multifaceted nature. The digital reading literacy assessment tests vary across the world. Implications for widely investigating adults and L2 reading literacy and relevant support or interventional measures to boost reading literacy were also discussed.

1. Introduction

The constantly developing and changing world requires us to master core abilities to adapt to them, and reading literacy forms a foundation of these critical competencies. It is the fundamental way and ability for people to acquire knowledge and develop skills for life in modern society [1]. In particular, reading literacy plays a vital role in self-improvement, professional development, education, and national development [2]. As information and communication technologies (ICTs) are developed and popularized, the concept of reading literacy is also changing over time. Nevertheless, old and new reading literacy are interwoven and complementary abilities, forming a single continuum of the same reading competence [3]. Competence in reading can also substantially impact the acquisition of other literacies, such as mathematics achievement [4].

However, since reading literacy has gained increasing popularity over recent decades, challenges associated with it were also noted as significant. Due to poverty, gender inequality, and historical and socioeconomic disadvantage, there is a general imbalance in the development of reading literacy ability across countries, regions, and individuals. Students with these disadvantageous backgrounds tended to lack the access and resources to form basic reading skills [5]. Studies have revealed that students were not equipped with the reading literacy skills needed to understand what they read and evaluate and synthesize information from various sources for higher education in South Africa. Great emphasis on teaching reading strategies to students has been placed [6,7]. Other educational challenges in Australia and New Zealand, comprising poor disciplinary climates, declining attitudes toward reading and a sense of belonging at school, and rising bullying, were also recognized as detrimental factors for reading [8].

Previous review studies conducted on reading literacy were found minimal after the keyword search of “reading literacy” and “review” was performed in several online databases, i.e., Web of Science, Sage, Google Scholar, and Emerald. Few have focused on a specific cohort of reading skills or digital reading. For example, Bartolucci (2021) analyzed the common reading skills that 15-year-olds acquired in Mexico [9]. Reiber-Kuijpers et al. (2021) centered on digital reading in a second or foreign language [10] (Table 1). To the best of our knowledge, there have been no review studies on reading literacy based on visualization citation networks. Hence, it is of great necessity to implement a comprehensive study to get a general understanding of reading literacy studies conducted worldwide to fill the research gap by using the method of visual citation network, which is meaningful for both present and future literature.

Table 1.

The comparison of previous review studies and this study.

2. Background

2.1. Organizations and Reading Literacy

Three acknowledged organizations have long been committing themselves to the development of the literacy of human beings. The first one is the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) which has pioneered literacy work over six decades in a general framework for human beings since 1946 [12]. The second is the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). Compared with UNESCO, IEA has centered more on the specific literacy category in the reading domain and has been at the forefront of comparative reading achievement studies across nations since 1970 [13] (p. 1). Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) are the two prominent projects conducted by IEA to assess fourth- and eighth-graders’ literacy in mathematics, science, and reading. The third is the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD launched the Programme for International Student Achievement (PISA) in 1997, which was linked to the Definition and Selection of Competencies (DeSeCo) Project. This project sorted the key competencies into three broad categories, i.e., use tools interactively (e.g., language, technology), interact in heterogeneous groups, and act autonomously. Reading literacy was illustrated as one of the key competencies in the PISA [14]. PIRLS, TIMSS, and PISA are three international assessment tests for children or adolescents’ literacy.

The definition of reading literacy can vary if it is grounded in different purposes and aimed at different groups. For example, PISA deemed reading literacy “the capacity to understand, use and reflect on written texts, to achieve one’s goals, develop one’s knowledge and potential, and participate in society” [14]. In PIRLS’s 2021 assessment framework, reading literacy was defined as “the ability to understand and use those written language forms required by society and/or valued by the individual. Readers can construct meaning from texts in a variety of forms. They read to learn, to participate in communities of readers in school and everyday life, and for enjoyment” [15]. PISA linked reading literacy to lifelong learning and measured 15-year-old students’ ability to apply literacy skills both in tests and in real life, while PIRLS focused on text-based reading and comprehension [16]. Despite the various objectives and testing objects, the core value of reading literacy was alike; that is, the emphasis was placed on the ability of a person to read for information and then get and apply what they need for development. In other words, reading literacy also underlies the acquirement of other crucial skills in life.

2.2. Reading Motivation

A successful reading performance might be attributed to a high reading amount, applications of different helpful reading strategies, and high reading self-efficacy. However, these factors failed to interpret all the reading performances. Anderson et al. (1985) pointed out that reading also required motivation [17] (p. 14). Reading motivation was seen as an individual’s personal goals, values, and beliefs concerning the topics, processes, and outcomes of reading [18] (p. 405). No matter whether in L1 or L2 reading, reading motivation was found essential for students’ reading engagement and performance [19,20,21].

Researchers have shown that reading motivation could affect reading outcomes with other factors and be affected by them at the same time. For instance, the best reading outcome could more possibly be obtained when L2 English learners had high intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and low reading anxiety. The high motivation was inclined to make up for the low reading efficiency incurred by reading anxiety [22]. Teachers’ activities or behavior, such as being a reading model, instructing reading strategies, and allowing students to choose materials, were correlated with adolescents’ reading motivation [23], and teacher autonomy support was particularly associated with intrinsic reading motivation among girls [24]. A family variable could also influence students’ reading motivation [25].

2.3. Digital Reading Literacy

With the development of technology, how we live and study has undergone tremendous changes. Internet use has become an indispensable part of our daily life in the 21st century, and the COVID-19 pandemic has forced us to depend more on it. Nevertheless, students were found more vulnerable to problematic Internet use during the pandemic in many countries than in previous studies conducted before the pandemic [26,27]. Today, ICT enables us to access online activities, such as playing games, e-mailing, instant chatting, blog updating, making new friends, and reading for information. The OECD (2009) has classified online reading activities into two types. One was social reading activities, e.g., using email and chatting. The other was information-seeking reading activities, e.g., searching for a particular topic and using an online dictionary [28].

Traditionally, reading literacy merely refers to basic print reading skills. However, as the latest definition of reading literacy in the PIRLS 2021 assessment framework stated, it has become a broader concept to keep up with the time, i.e., to be able to read print and digital reading materials. The research on digital reading characterized reading and the manipulation of reading devices, the navigation skills within the text, and the search for other digital texts [29]. Therefore, it was seen as not the same thing as traditional paper reading [30]. It has been concluded that students tended to achieve better scores when they read print materials than digital ones [31].

The two pioneer international assessments, PISA and PIRLS, applied different types of texts and questions to measure reading literacy traditionally. For instance, PISA 2000 focused on the retrieval, interpretation, and reflection/evaluation of texts. Continuous and non-continuous texts and multiple-choice and constructed-response questions were used. PIRLS focused on three aspects of reading: the purposes for reading, the processes of comprehension, and reading behavior and attitudes. Expository texts were used to test the purpose of acquiring and using information, while narrative texts were for literacy experience purposes. Both of these international assessments of reading literacy included a background questionnaire for schools and parents (PIRLS also included teachers’ feedback) to explore the external factors that might explain students’ reading competence [32].

However, given the different nature of reading in print and digital forms, the standard assessment of students’ offline reading competence could no more be used to measure online reading comprehension skills [33]. Both PIRLS and PISA have extended the assessment on digital reading. Based on the PIRLS 2016 Assessment Framework, ePIRLS 2016 was designed to “use an engaging, simulated Internet environment to present fourth-grade students with authentic school-like assignments involving science and social studies topics” [34]. PISA 2009 included a comprehensive assessment of digital reading literacy on a large scale, such as whether backgrounds, familiarity, and use of information and communication technologies influence their reading outcomes. The results show that many students failed to integrate and evaluate information and did not perform well in completing online reading tasks [30]. Therefore, it is necessary to measure online reading literacy and find solutions to improve it.

3. Research Questions

Although reading literacy has received early attention since the 20th century, we do not know whether the research on it is increasing as time goes by globally. In addition, reading literacy can be a big concept or scope which might change over time due to the development of society. The countries with the highest number of publications, heated topics, frequently cited references and keywords, etc., in this field have remained poorly investigated. To get a better grasp of reading literacy research in the big picture, the authors, hence, proposed the following research questions:

RQ1. What is the trend of publications and citations by year in reading literacy research?

RQ2. What are the top ten cited organizations, cited countries, cited author keywords, cited references, cited sources, and cited authors in reading literacy research?

RQ3. What are the top ten countries with the highest number of publications regarding reading literacy studies?

RQ4. What are the heated topics/subjects related to reading literacy studies?

Considering the various highlights in the previous studies pertaining to reading motivation in reading comprehension, the authors, hence, explore its role in reading literacy literature specifically and propose the following research question:

RQ5. Does reading motivation play a significant role in reading literacy?

Technology makes it possible for people to participate in various kinds of activities. Online activities could be entertaining, relaxing, and informative. The amount of time we spend reading online is also increasing in this day and age. However, whether all kinds of online reading activities help improve digital reading literacy warrants scrutiny to unravel the different impacts among them. In addition to international online assessment tests, there may be other more specific tests or tools for assessing digital reading literacy across regions or nations to cater to the needs of the changing society. The authors, hence, proposed the following research questions:

RQ6. Do online reading activities facilitate digital reading literacy?

RQ7. How can digital reading literacy be assessed or measured across nations?

4. Materials and Methods

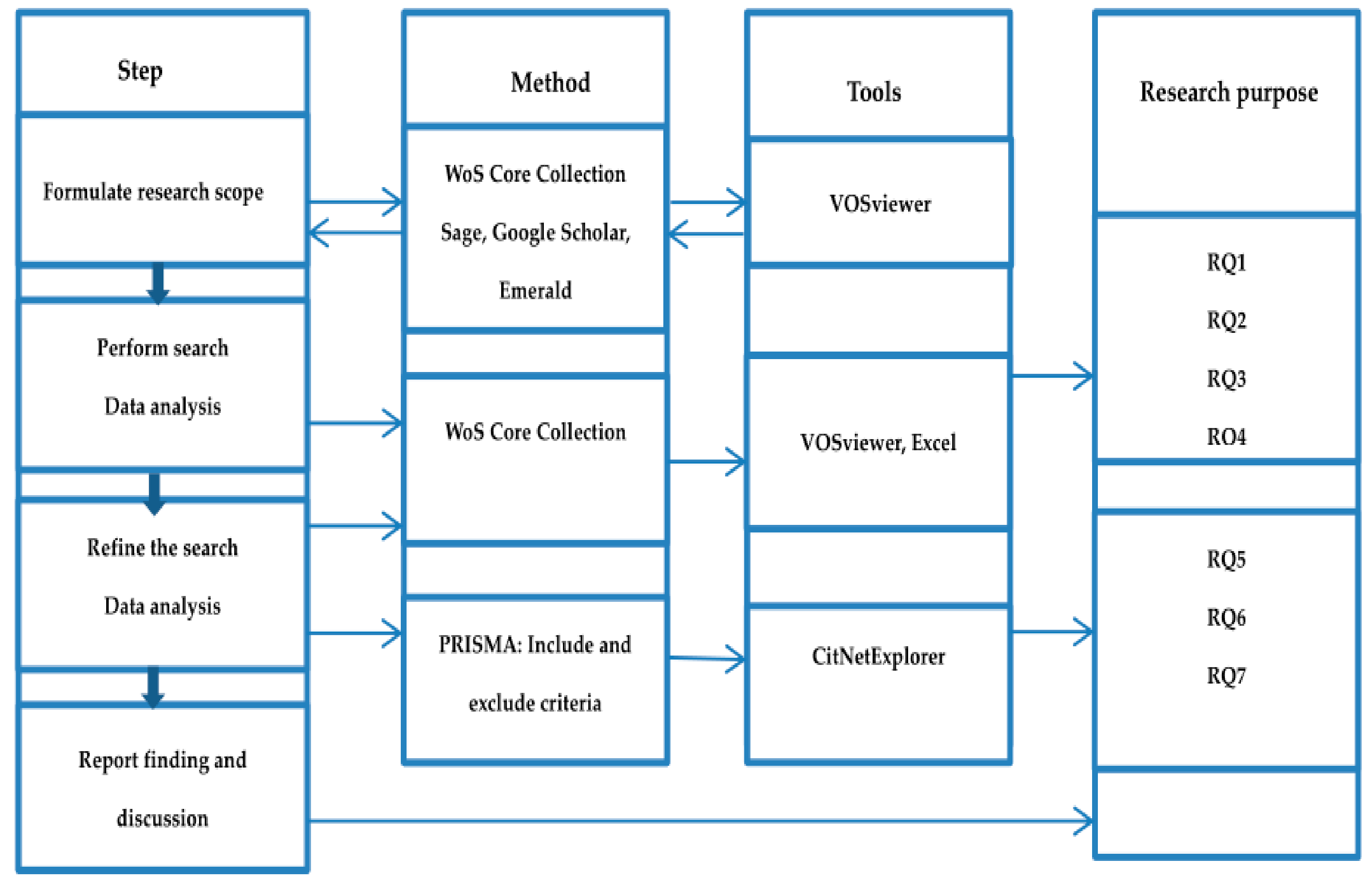

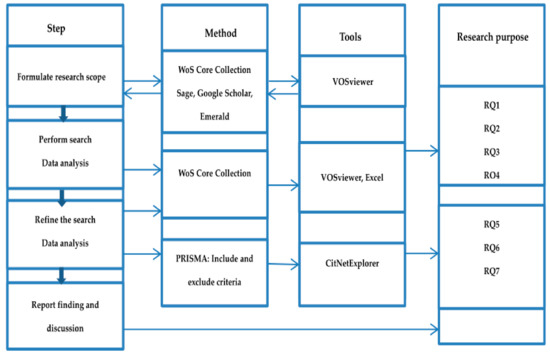

Roughly, four research steps were used for this study (Figure 1). The formulation of the research scope/theme was based on the theme search of reading literacy in various online databases, i.e., Web of Science, Sage, Google Scholar, and Emerald. The steps methods, tools, and corresponding research objectives are explained in detail below.

Figure 1.

Research steps, methods, and tools.

This review study was carried out on the basis of the existing literature in the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection database. To better understand this research area’s evolution, the researchers employed a bibliometric analysis based on the citation network using VOSviewer and CitNetExplorer tools [35,36]. Both types of software can visualize and encourage the analysis of clustering outcomes. CitNetExplorer could greatly facilitate the visualization of cited publications based on their citation relations at an individual level, while VOSviewer analyzed clustering results at an aggregate level. With their powerful functionalities on clustering and computation of massive studies, combining the two software tools could be conducive to analyzing literature in many research fields [37].

Specifically, to answer the first four research questions, the researchers mainly used VOSviewer and Microsoft Excel as auxiliary tools. For research questions five to seven which involved literature screening and required a more microscopic study, the researchers applied CitNetExplorer software. Meanwhile, the inclusion and exclusion of extant literature were based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Protocol (PRISMA-P). PRISMA-P is a guideline for implementing systematic reviews developed by several international researchers, containing different parts and their thorough explanations of a review study, such as title, abstract, introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion [38,39].

To attain relevant studies with regard to reading literacy, the researchers searched in the WoS Core Collection on 30 October 2022. By keying in the keywords “reading literacy” as the topic, 469 results were obtained, including 443 articles, 10 early-access documents, 5 book reviews, 5 review articles, 3 meeting abstracts, 2 editorial materials, 2 proceeding papers, and 1 correction, ranging from 2008 to 2022.

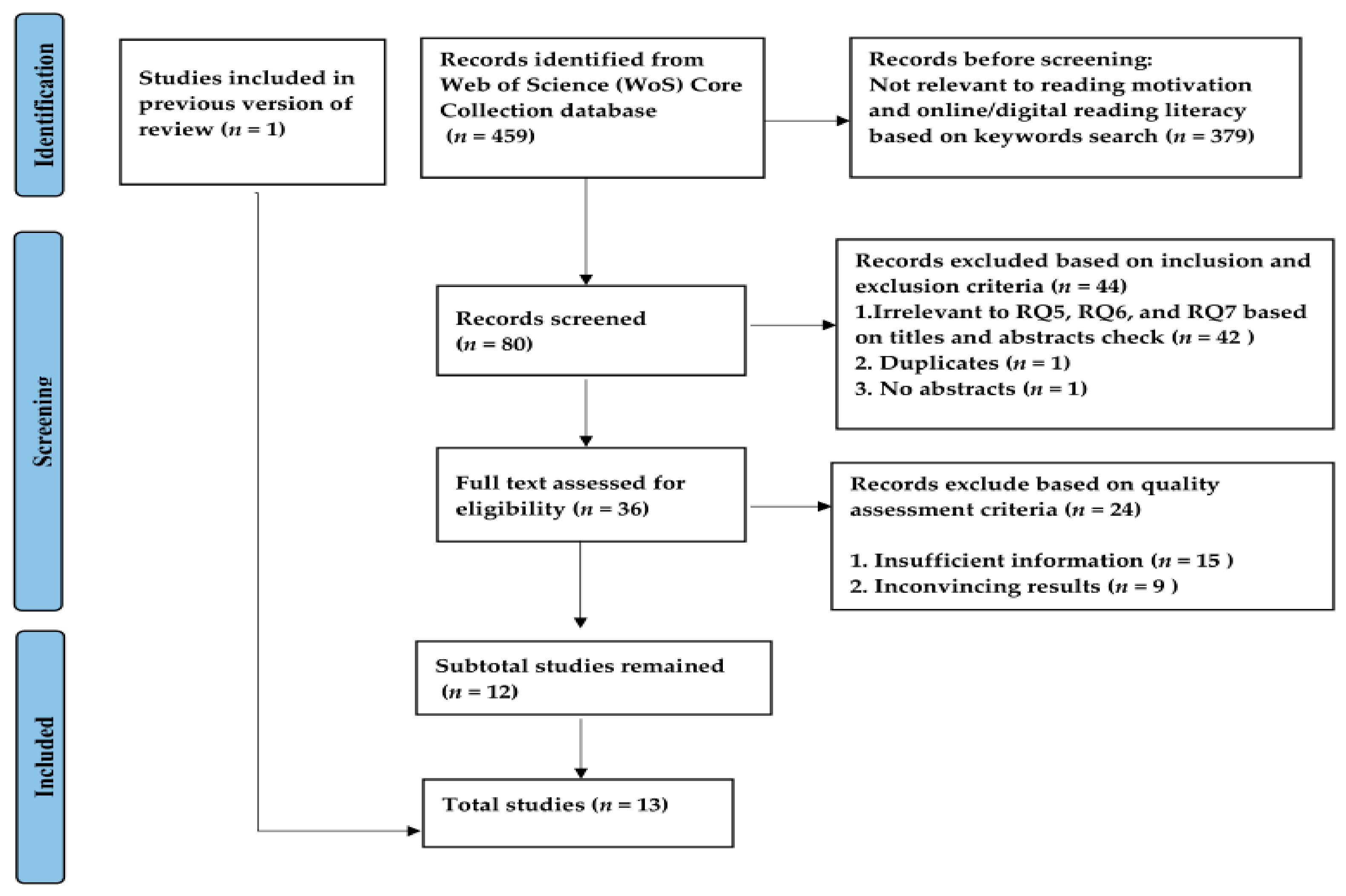

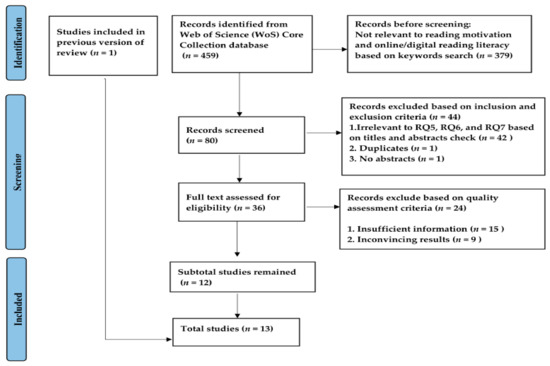

However, the ten early-access documents needed to be excluded to avoid the null pointer exception problem that might occur when using the CitNetExplorer tool. Despite that VOSviewer would not have such a problem, considering the small number of early-access documents (n = 10); only 459 results were further exported to VOSviewer for bibliometric analysis to answer research questions one to four (Research question 3 used 475 publications extracted from the database on 11 December 2022 to analyze the publications across countries). Afterward, the researchers refined the search by keeping the previous keyword of “reading literacy” as the topic and adding “reading motivation” and “digital OR online” as the topics, respectively. Under the scope of reading literacy, 27 publications related to reading motivation and 53 publications relevant to digital or online reading were obtained. Answering research questions five to seven required pertinent literature with regard to the role of reading motivation and online reading activities in (digital) reading literacy and assessment tests for it. Therefore, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were implemented carefully. Studies were excluded if they (1) were not related to at least one research question (5–7); (2) were duplicates; (3) had no abstracts; or (4) were not found in full text. Studies were included if they (1) were mostly from high-impact journals; (2) were rigidly designed; and (3) had enough information and compelling results. Finally, 13 results were obtained (Appendix A). The selection process is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A flow chart of the literature inclusion based on PRISMA-P.

5. Results

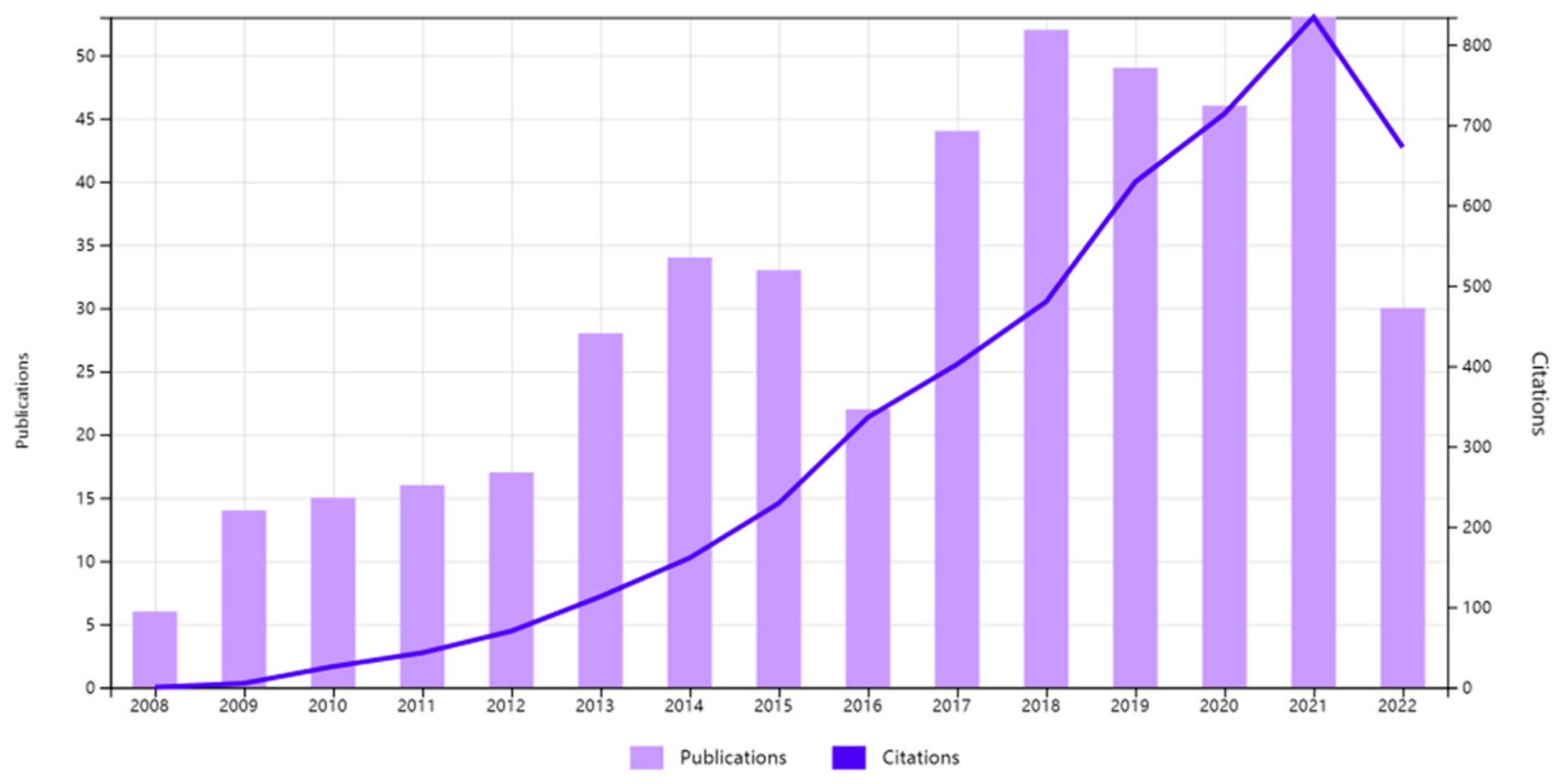

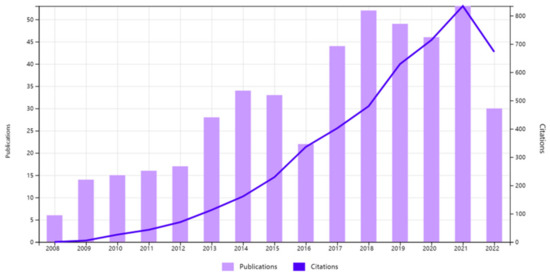

5.1. RQ1. What Is the Trend of Publications and Citations by Year in Reading Literacy Research?

As it is shown in Figure 3, annual trends in publications and citations varied. The number of publications increased, albeit with fluctuations in some years. In particular, with six publications in the year 2008, reading literacy studies began to gain attention. Moreover, the number of publications suddenly doubled in 2009. From 2009 to 2012, the number of publications increased only by one per year, indicating that research on reading literacy was growing at a languid pace. Although it showed a sudden burst from 2013 to 2014, the publications decreased in 2015, and 2016 was the second year with the lowest number of publications except for its debut in 2008. In 2017 and 2018, the publications began to soar again but descended in 2019 and 2020. The publication’s peak was in 2021. However, data up to the end of October 2022 in WoS Core Collection showed a significant decline in the number of studies in 2022. Nevertheless, compared with the publications, the citations tended to increase steadily year by year, except in 2022. The citation peak overlapped with the publications peak in 2021, while 2022 seemed to have experienced a sharp decline in citations.

Figure 3.

Times cited and publications from 2008 to the end of October 2022.

5.2. RQ2. What Are the Top Ten Cited Organizations, Cited Countries, Author Keywords, Cited References, Cited Sources, and Cited Authors in Reading Literacy Research?

Using the counting methods and clustering technique in VOSviewer, the researchers obtained the results of the top ten cited organizations, cited countries, author keywords, cited references, cited sources, and cited authors (Table 2). The top ten organizations were the Free University of Berlin, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, University of Valencia, Chinese University of Hong Kong, University of Hong Kong, National Chiao Tung University, Humboldt University of Berlin, German Institute for International Educational Research, Beijing Normal University, and the University of Jyväskylä. The top ten countries were Germany, the USA, China, England, Australia, Spain, the Netherlands, Canada, Italy, and Sweden. The top ten author keywords were reading literacy, PISA, reading, reading comprehension, PIRLS, literacy, assessment, reading motivation, gender, and reading achievement.

Table 2.

The top ten organizations, countries, author keywords, cited references, cited sources, and cited authors.

The top ten cited references were the PIRLS 2006 International Report, PIRLS 2011 International Results in Reading, PIRLS 2011 Assessment Framework, Comprehension: A paradigm for cognition, PIRLS 2001 International report, Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement, Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, Socioeconomic status, and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research, Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, and Parental Involvement in the Development of Children’s Reading Skill: A Five Year Longitudinal Study. The top ten cited sources were the Journal of Educational Psychology, Reading Research Quarterly, Review of Educational Research, Computers & Education, Reading and Writing, Child Development, Learning and Individual Differences, Scientific Studies of Reading, Reading Teacher, and Learning and Instruction. The top ten cited authors were OECD, Mullis, I.V.S., Guthrie, J. T., Marsh, H.W., Wigfield, A., Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Baumert, J., Baker, L., Kintsch, W., and Senechal, M.

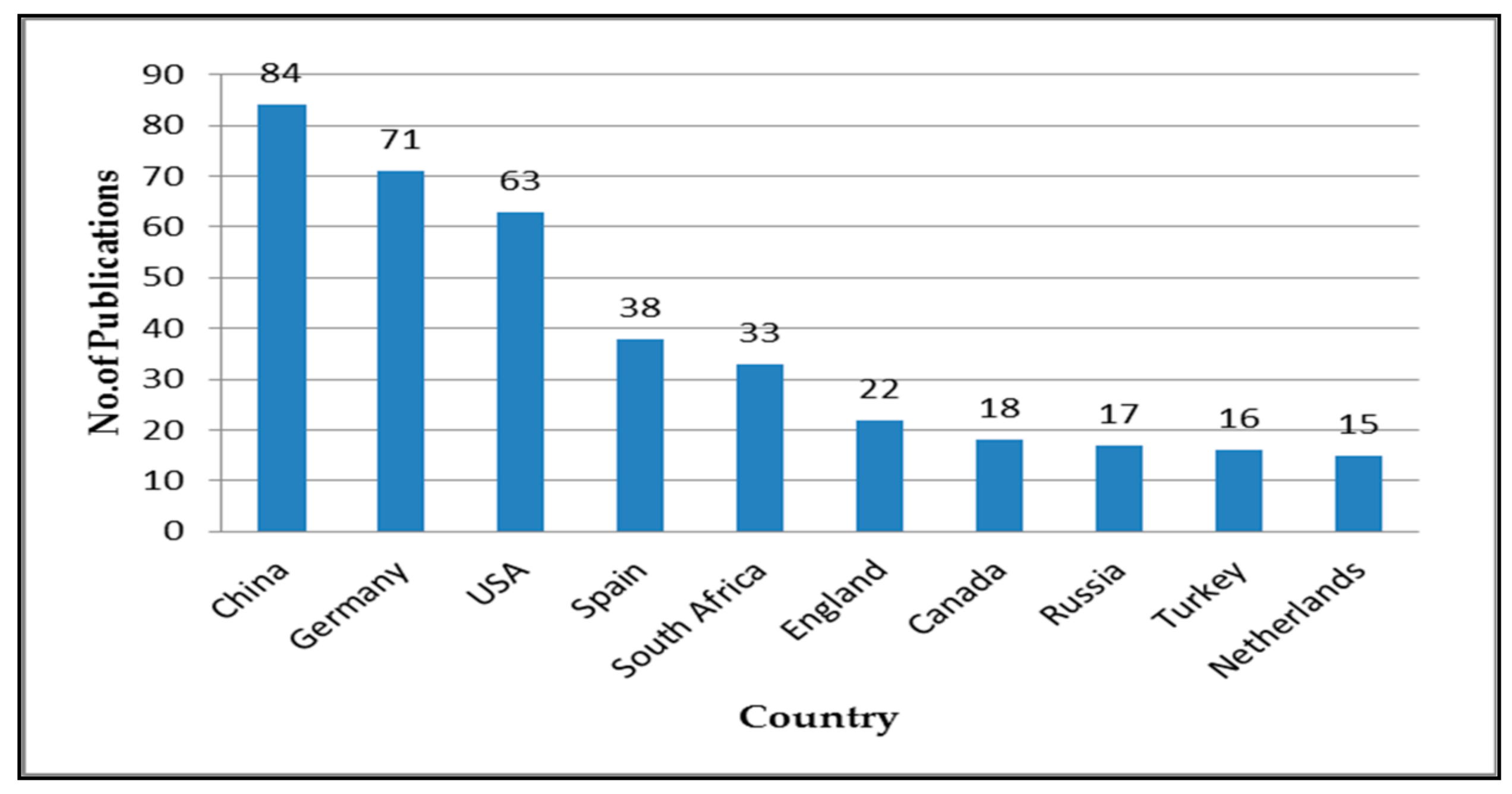

5.3. RQ3. What Are the Top Ten Countries with the Highest Number of Publications Regarding Reading Literacy Studies?

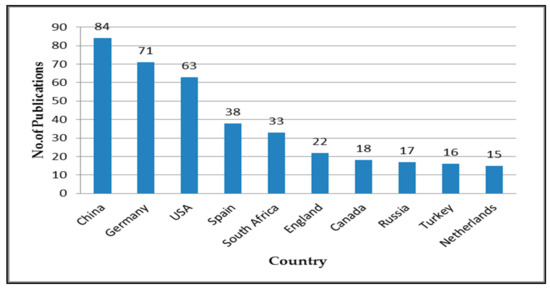

To answer this question, the researchers obtained 475 results by entering the keyword “reading literacy” in the online database WoS Core Collection on 11 December 2022. As it is shown in Figure 4, the top ten countries with the highest number of publications, in descending order, were China (n = 84), Germany (n = 71), the USA (n = 63), Spain (n = 38), South Africa (n = 33), England (n = 22), Canada (n = 18), Russia (n = 17), Turkey (n = 16), and Netherlands (n = 15). The subtotal number of these publications was 377, accounting for more than 79% of the total. Some differences in the number of publications between the top ten countries were also striking. For example, the total number of publications in the top three ones still outnumbered the bottom seven (218 vs. 159). The number of publications for each of the latter five countries was roughly equal, which was almost three to four times fewer than the top three countries, i.e., China, Germany, and the USA.

Figure 4.

The top ten countries with the highest number of publications.

5.4. RQ4. What Are the Heated Topics/Subjects Relating to Reading Literacy Studies?

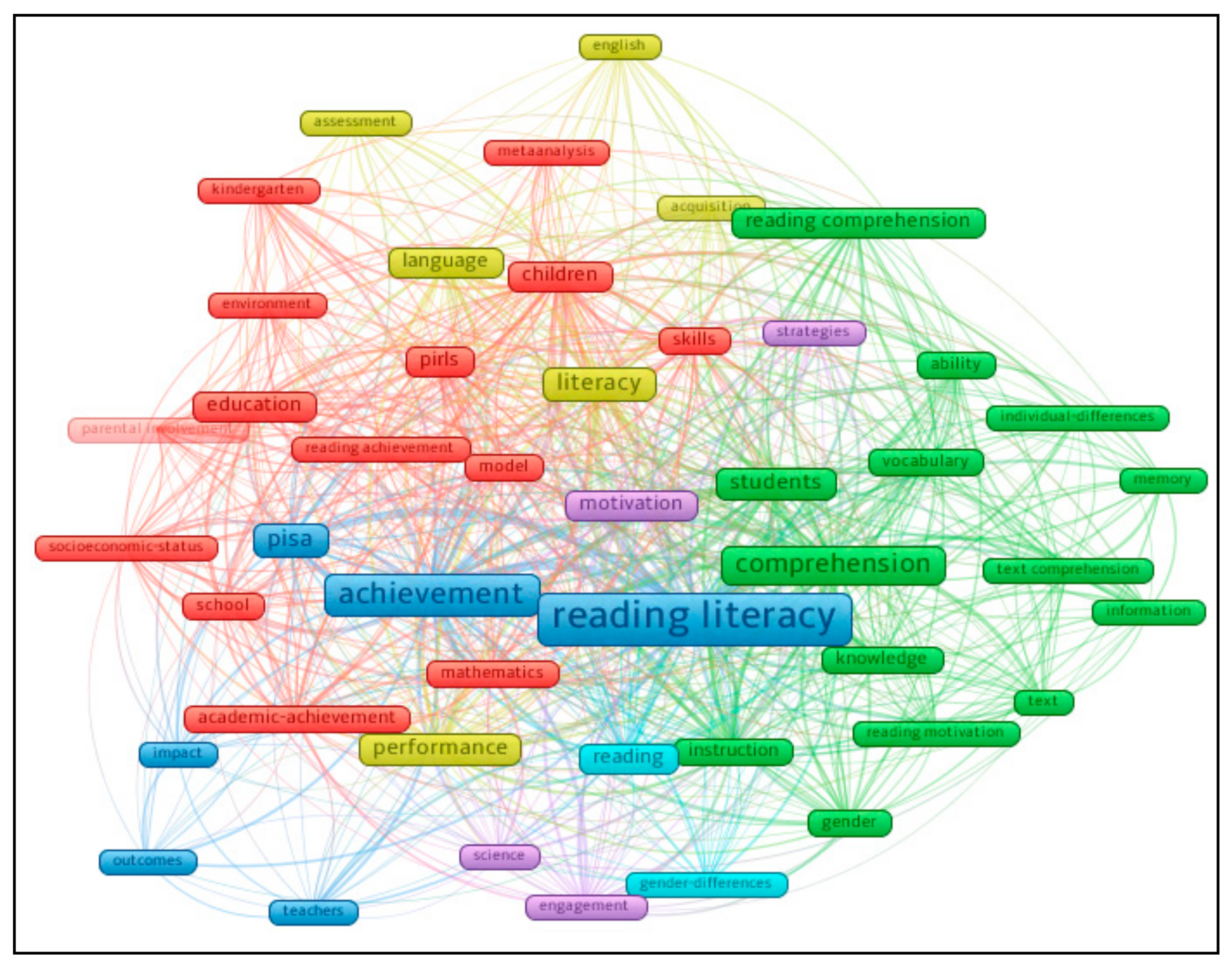

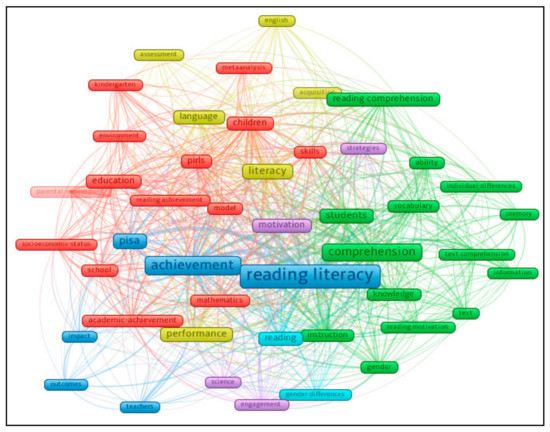

To visualize the heated topics/subjects, the researchers employed Co-occurrence as the type of analysis, All Keywords as the unit of analysis, and Full counting as the counting method in VOSviewer. The minimum number of occurrences of a keyword was set at ten. Of the 2012 keywords, 47 met the threshold. For each of the 47 keywords, the total strength of the co-occurrence links with other keywords was calculated. The keywords with the greatest total link strength were selected. The keyword map was obtained as shown in Figure 5. The size of the frame represents the number of publications, the color reflects a cluster, and the distance and total link strength between items reveal correlations. For instance, closely related topics are located nearer [40].

Figure 5.

A clustering map of keywords co-occurring ≥10 times in 459 publications.

The top ten keywords and the heated subjects with the strongest total strength were achievement (Link = 309, Occurrences = 82), reading literacy (Link = 297, Occurrences = 121), comprehension (Link = 235, Occurrences = 66), students (Link = 186, Occurrences = 45), children (Link = 177, Occurrences = 40), literacy (Link = 175, Occurrences = 50), performance (Link =161, Occurrences = 47), instruction (Link = 147, Occurrences = 32), motivation (Link = 137, Occurrences = 33), and education (Link = 121, Occurrences = 39). Specifically, six theme clusters totaling 47 items were grouped. Cluster 1 (15 items) included academic-achievement, attitudes, children, education, environment, kindergarten, mathematics, meta-analysis, model, parental involvement, PIRLS, reading achievement, school, skills, and socioeconomic-status. Cluster 2 (14 items) included ability, comprehension, gender, individual-differences, information, instruction, knowledge, memory, reading comprehension, reading motivation, students, text, text comprehension, and vocabulary. Cluster 3 (six items) included achievement, impact, outcomes, PISA, reading literacy, and teachers. Cluster 4 (six items) comprised acquisition, assessment, English, language, literacy, and performance. Cluster 5 (four items) contained engagement, motivation, science, and strategies. Cluster 6 (two items) included gender-differences and reading.

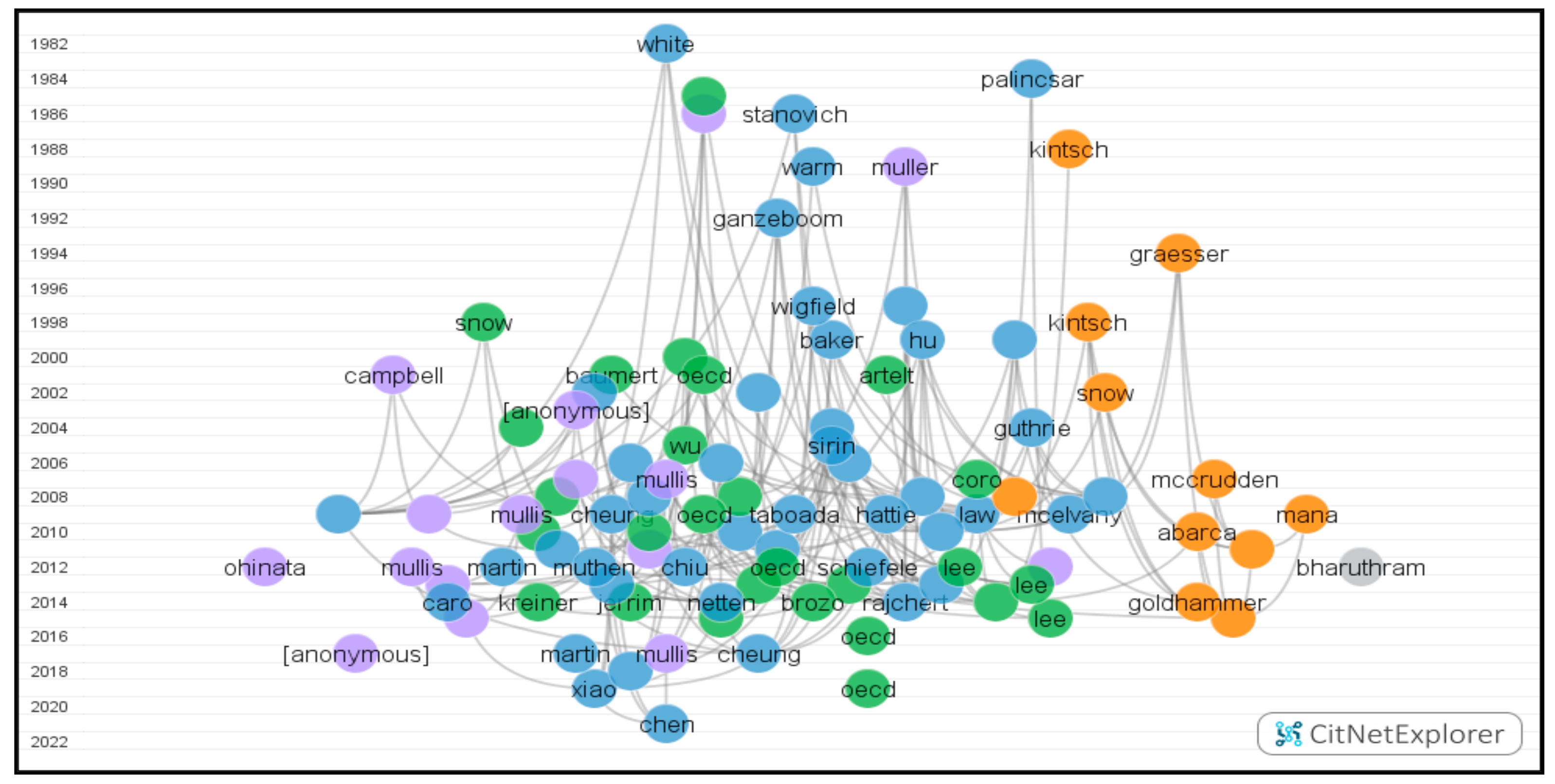

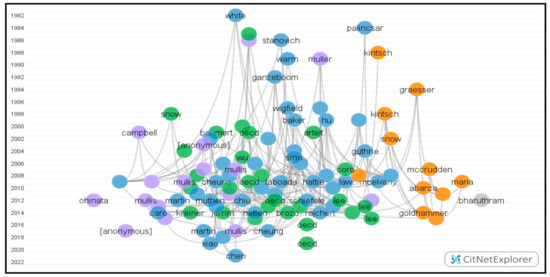

Using the clustering technique in CitNetExplorer, 516 publications with 1199 citation links were obtained from 1982 to 2022. The included publications were identified as four clusters in total. However, due to the minimum size requirement, 121 publications did not belong to a cluster. Table 3 below demonstrates the details of the four clusters in terms of the number of publications, number of citation links, number of publications significant than or equal to 10 citations, and the number of publications in the 100 most cited publications. After setting 100 as the number of publications, the visualization citation network was acquired (Figure 6). The circles represent publications named after the first author’s family name, and the curved lines connecting them indicate citation relations. The vertical axis represents the publication time which decided the circle’s location vertically. Citations always moved upward, i.e., a cited publication situated above a citing publication. The distribution of publications horizontally depends on each publication’s connection degree. Namely, the closer the circles are located to each other, the closer the publications are linked to each other [35].

Table 3.

Citation network information of the four clusters.

Figure 6.

One hundred most cited publications in the visualization citation network.

To take a closer look at the specific topic in the citation network, i.e., to answer the following research questions, in this case, the researchers implemented the Drill Down and Longest Path functionalities in CitNetExplorer. The results of the operations are discussed in the following sections with regard to the findings to research questions 5, 6, and 7.

5.5. RQ5. Does Reading Motivation Play a Significant Role in Reading Literacy?

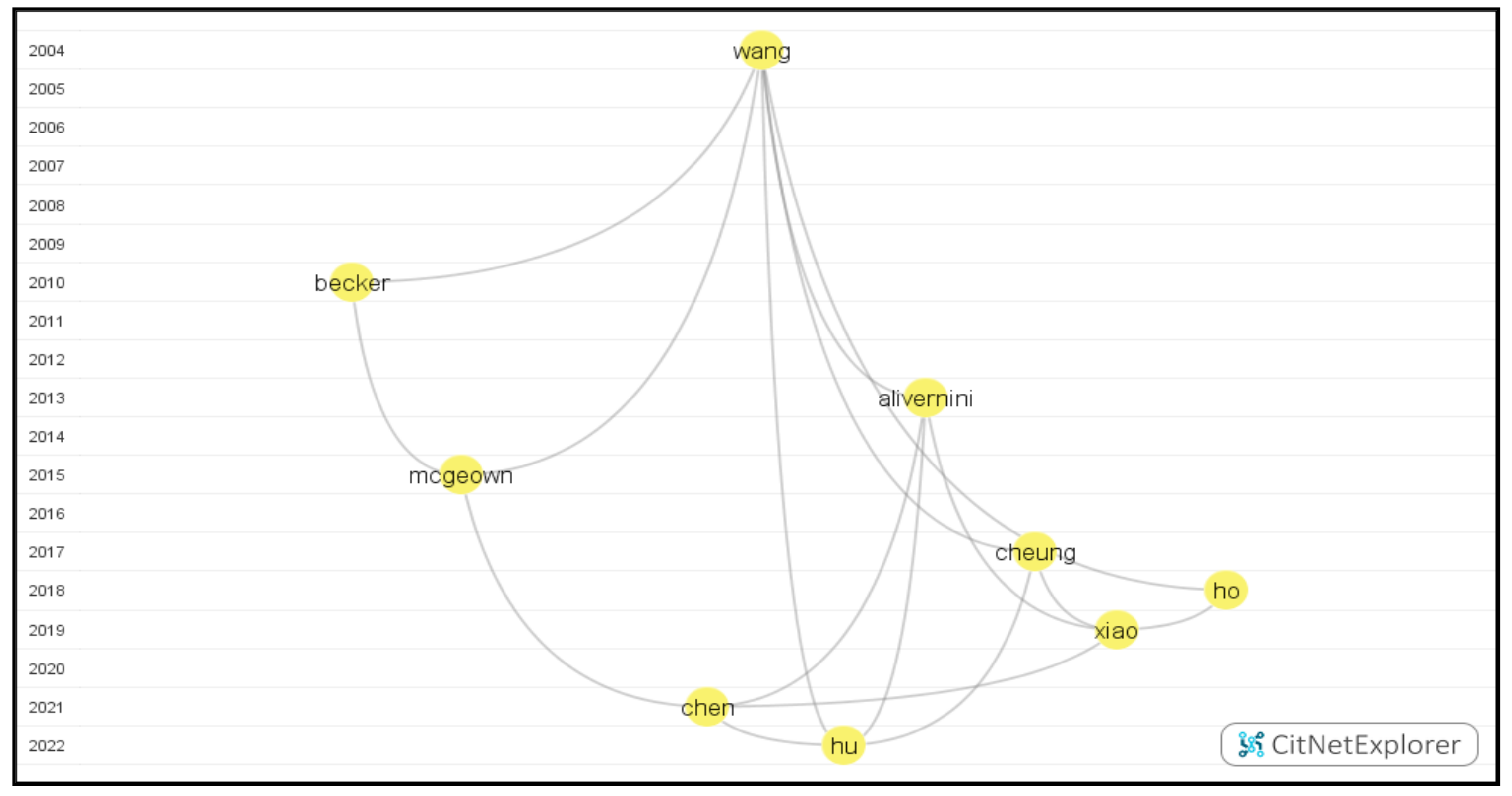

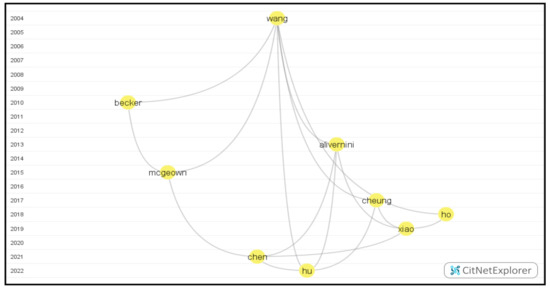

By drilling down the first cluster and finding the longest path between the latest publications by Hu [41] and the publication by Wang & Guthrie farthest from it in the vertical distance [42], we obtained the first longest path (Figure 7) with nine publications.

Figure 7.

The visualization of the first longest path.

As one of the decisive factors, reading motivation could explain the development of reading achievement [43] among both L1 and L2 learners [21]. With other factors, such as self-efficacy, metacognitive reading strategies, and self-confidence, reading motivation could predict reading achievement well [44,45]. A longitudinal study suggested that reading literacy in higher grades could be predicted by intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation in an earlier grade. While intrinsic motivation positively influenced reading literacy in Grade 6 mediated by reading amount, extrinsic motivation was negatively related to reading literacy. There was a bidirectional relationship between reading motivation and reading literacy. Early reading literacy was found to be negatively correlated with extrinsic reading motivation and negatively related to reading performance in higher grades [46]. Intrinsic reading motivation and reading achievement were positively linked in Grade 3 [47].

Gender differences in reading motivation were also found significant in reading literacy achievement. Females tended to have a relatively higher intrinsic reading motivation than their male counterparts, which could further affect their reading literacy [48,49,50].

5.6. RQ6. Do Online Reading Activities Facilitate Digital Reading Literacy?

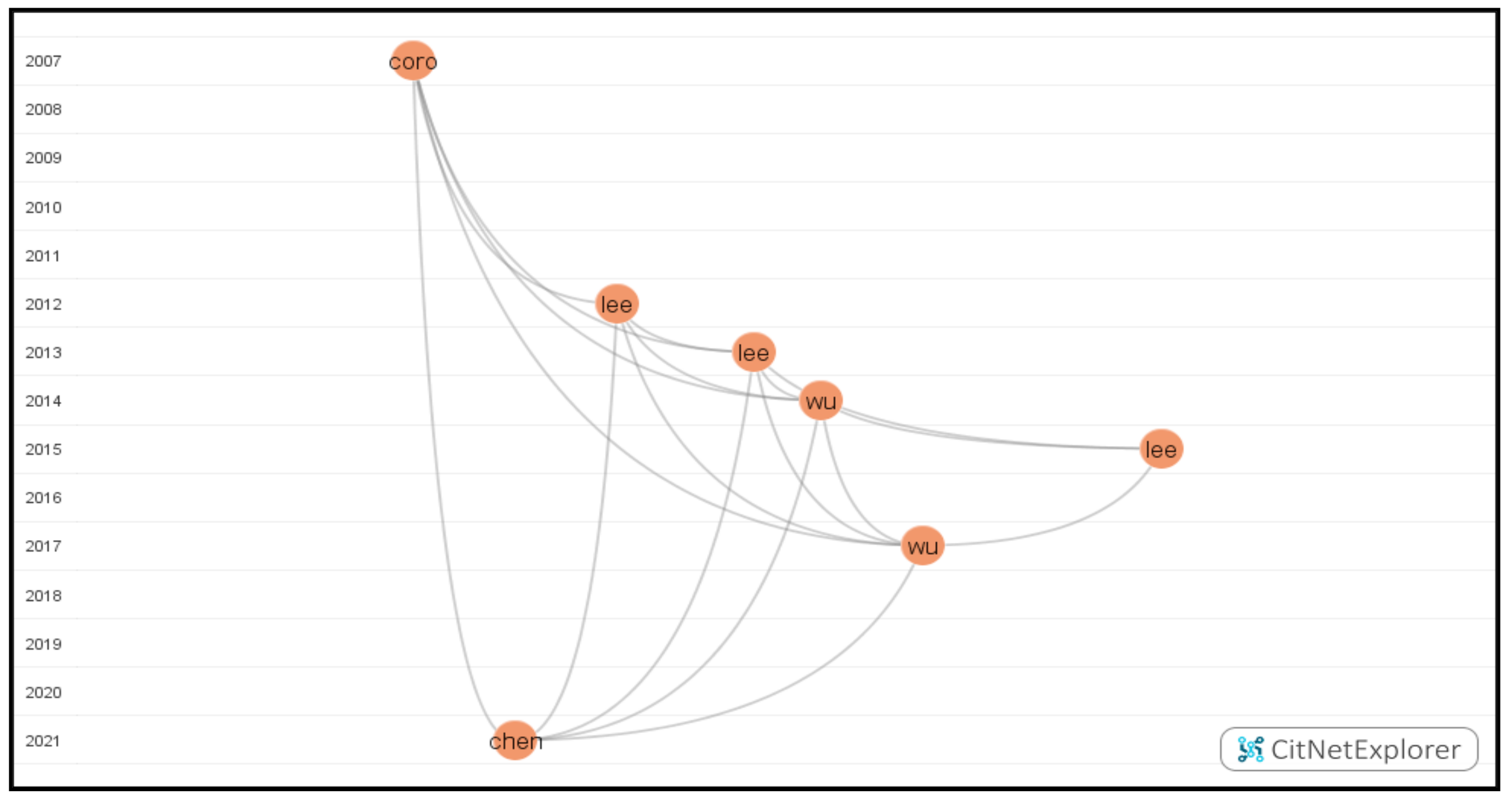

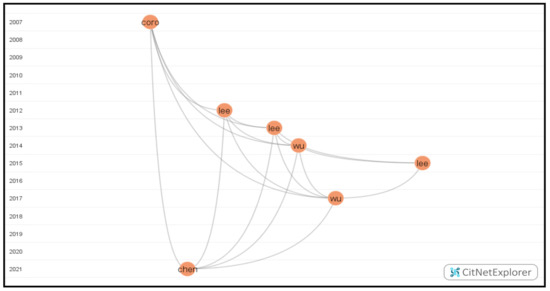

To address this research question, we drilled down the green cluster and identified the second-longest path by selecting the publications of Coiro [51] and Chen [52]. As shown in Figure 8, this citation network included seven publications.

Figure 8.

The visualization of the second-longest path.

Online reading activities play an essential role in reading literacy. Lee and Wu (2012) revealed that online reading engagement and reading literacy were positively affected by individual differences in favorable attitudes toward computers and confidence in the use of ICT. With the increasing engagement in online reading, students gradually transformed online reading skills into printed reading texts [53]. It has been found that the information-seeking reading activities facilitated a positive insight into metacognitive strategy use and further led to higher reading literacy with navigation skills both in printed and electronic reading assessment [54] across regions based on the PISA 2009 database [55]. Besides, technological support was suggested to encourage students’ critical thinking of science reading literacy in a collaborative learning environment [56]. The integration of digital reading of audiobooks and e-books could as well develop and sustain juveniles’ reading endurance, vocabulary, and motivation [57]. Surprisingly, computer games could also boost better performance among 15-year-old boys in digital reading [58].

However, not all online reading activities could positively enhance reading competence. For example, social entertainment reading activities were found not beneficial for reading literacy [59]. Furthermore, easy access to ICT at home could indirectly affect reading literacy. In particular, ICT can only facilitate reading literacy when students engage in online reading activities. When it comes to a particular form of ICT, according to the 2009 and 2018 PISA databases, due to the increasing rise in online chatting, reading achievements and awareness of reading strategy among teenagers were found to deteriorate nationwide [60].

5.7. RQ.7 How Can Digital Reading Literacy Be Assessed or Measured across Nations?

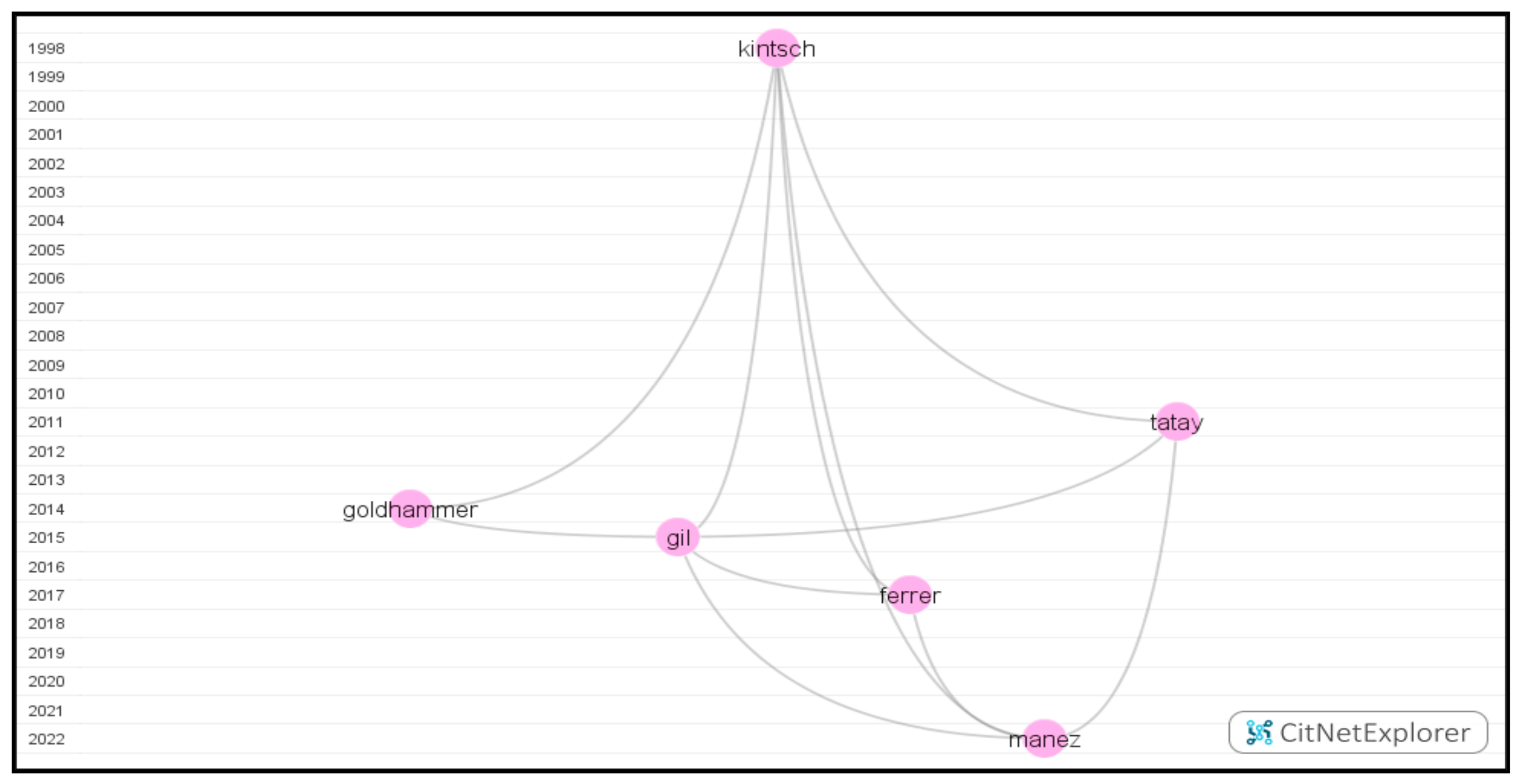

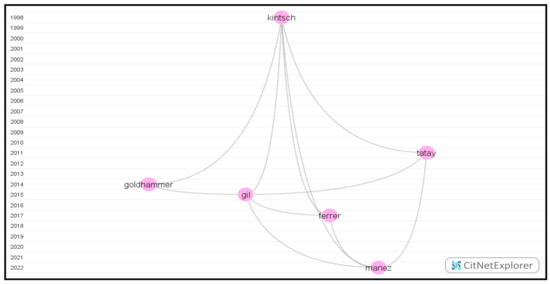

To answer this research question, the researchers drilled down the orange cluster, and the longest path with six publications (Figure 9) was spotted by selecting Kintsch [61] and the latest publication Manez [62]. With the prevalence of the Internet, how digital reading literacy can be assessed and measured gained increasing attention. Several assessment tools or tests have already been developed and validated in different contexts over time. Initiated by the United States, the

Online

Reading

Comprehension

Assessment (ORCA) project was aimed at assessing and measuring online reading comprehension by using three assessment formats. Eight

alternative

scenarios common to American seventh-graders with a specific inquiry question were developed. Around 45-minute answer time was left for each scenario experience to assess their ability to locate, evaluate, synthesize, and communicate information [63], and inspired by this project, ORCA.IT (Italian version) was developed and tested adolescents’ online reading comprehension among those with or without reading difficulties across three types of schools. Compared with the previous ORCA, it extended interesting topics outside the school curriculum, and the testing device included a Text to Speech function to help those who had reading difficulties. Besides, the scores were calculated automatically [64].

Figure 9.

The visualization of the third-longest path.

Some online reading literacy tests have also been developed and validated based on the PISA reading assessment framework. Three aspects of reading were taken into account when formulating the questions, i.e., access and retrieval, integration and interpretation, and reflection and evaluation. The Web reading literacy test (WebLEC) was designed to measure Spanish children’s online reading literacy skills [40]. Twenty-eight questions (2 open-ended and 20 multiple-choice) regarding the above three aspects were attached to four distinct reading scenarios (e.g., Forums, Wikipedia, Youth Web, and Google). A general reading index was provided, and two students’ navigation indicators were added to this test. Besides, the Online Reading Literacy Assessment (ORLA) also proved to be effective but a little difficult for Chinese eighth-graders [65]. Two subsets for three aspects of reading were included, i.e., Web-page information reading (six multiple-choice questions) and online reading and communicating (three open-ended and six multiple-choice questions). Except for the PISA framework, a standardized paper-and-pencil Spanish reading literacy test (CompLEC) [66] was also a prototype for a new computer-based reading literacy test (e-CompLEC). It was developed to assess online strategic reading literacy skills by using a moving window technique, Read & Answer [67]. Three continuous texts with verbal information and two non-continuous texts with both iconic and verbal information, totaling 20 questions (3 open-ended and 17 multiple-choice), were included.

6. Discussion

6.1. Suggestions from Bibliometric Analysis

The year trend of the publications and citations, the top ten organizations, countries, author keywords, all keywords, cited references, cited sources, and cited authors found in this study could give insight for future studies in reading literacy. For example, the co-occurrence of keywords analysis presented an overview of heated topics related to reading literacy. From the six clusters of the keyword map, we can see that the most discussed topics were achievement, reading comprehension, motivation, students, etc. This showed that the context of reading literacy studies is mostly school-related. Researchers could consider exploring reading literacy outside of school. Topics that receive less attention could be spotted and further explored as well. For instance, the interdisciplinary study of reading literacy had only two keywords of the discipline emerging, i.e., mathematics and science. The role of reading literacy in other disciplines is worth thinking about and studying.

Researchers can also conduct in-depth studies based on the high citation scores among cited references, sources, and authors. Taking the ten top organizations for a closer look, 4 out of 10 were German organizations, which suggests that great emphasis has been placed on reading research and might account for the inception of publication on reading literacy in 2008, shown in Figure 3. Therefore, future research can focus on the substantial studies that these German organizations have conducted for reading.

The top ten countries with the highest publications also indicated the active extent of countries on reading literacy research. From the results, it is concluded that these countries participated in at least one international assessment program in the past three to four cycles, namely PIRLS, PISA, and TIMSS. By participating in these programs, each country could further conduct relevant studies based on the achievement results, as well as country-specific review studies. Taking China as an example, different regions successively or simultaneously took part in PISA, TIMSS, and PIRLS since the first cycle, e.g., Hong Kong in TIMSS 1995, PISA 2000, and PIRLS 2001, Macau in PISA 2003, Shanghai in PISA 2009, and Chinese Taipei in PIRLS 2006. The results show that China was among the best-performing countries. However, reading literacy performance in undeveloped, rural areas has triggered concerns. For instance, the sample data from Shaanxi, Guizhou, and Jiangxi provinces indicated that reading achievement in remote regions was below the reading literacy levels of any other participating countries in PIRLS [68].

6.2. Reading Motivation

Reading motivation is important and malleable in cultivating students’ reading literacy. Challenges might emerge along the way. For example, peer influence might go both ways; that is, a positive/negative perception of the peer group’s attitude toward reading could explain their reading motivation [69,70]. Plus, the decline in motivation was evidenced in previous reading studies as they aged [71]. The possible cause of gender differences between boys and girls could also pose a threat to reading efforts. The Interests as Identity Regulation Model and Stereotype Threat theory concluded that the identification of gender stereotypes affected the behavior of boys and girls in some specific domain, e.g., female stereotyping to excel in reading could lead to lesser male identification and engagement in this field [72,73]. However, based on the above findings, effective measures can be taken to foster reading motivation. For example, teachers’ activities can be appropriately adjusted to accommodate these challenges.

6.3. Assessment Test for Digital Reading Literacy

Although PISA 2009 and PIRLS 2016 have piloted online assessment tests for adolescents, different types of assessment tests for digital reading literacy were subsequently developed to cater to the changing nature from print reading to online reading. There seems to be a tendency for each country or nation to develop its digital reading literacy test, which is necessary. On the one hand, regarding the existing international tests, a challenge has been spotted that measurement invariance might influence the prediction model and the validity of large-scale assessment studies in educational achievement investigations across nations. A theoretical framework for measuring the home resource for a learning index was strongly recommended for further application based on a particular country or nation [74]. It would be hard for a unified test to consider everything once and for all. On the other hand, as Coiro (2009) pointed out, rapidly advancing technologies will constantly bring changes to online texts, tools, and reading contexts, which pose an ultimate challenge in assessing digital reading competence [33].

However, according to the existing literature, different assessment tests were still in their primary stage, i.e., being developed and validated among a limited number of samples. Nationwide implementation and the effect of these tests on the performance in terms of response time and question format (open-end or multiple-choice), etc., are still unknown.

6.4. Research Group of Reading Literacy

The findings on the role of reading motivation, online reading activities, and the assessment of digital reading literacy almost all point to a similar cohort, i.e., adolescents. One explanation for this would be that the studies of reading literacy among young people have received tremendous attention across nations. The influential international tests for reading literacy are designed for adolescents, e.g., PIRLS for fourth-graders and PISA for 15-year-olds. Many studies were carried out based on the performance of these tests. Meanwhile, as teenagers, their worldviews, reading literacy, and other ability aspects are shaped during adolescence. Compared with adults, therefore, they are also the most vulnerable to external influences, such as from schools, parents, and peer groups. Therefore, the extrinsic motivation formed by an external force, e.g., to meet the requirements of their parents, casts a significant impact on their reading literacy.

In terms of Internet use, young people have been exposed to online activities since they were born in an era of great technological prosperity and development. On this basis, they are called “digital natives”. However, being exposed to a high-frequency use of the technology environment does not guarantee a high level of basic digital reading skills which is directly related to digital reading literacy [75]. Besides, this cohort also tended to be more susceptible to problematic Internet use without proper guidance [76]. They might stray away from educational-purpose-based activities, become aggressors or victims of cyberbullying [77,78], and become addicted to Internet games [79]. Even when they engage in online reading activities, there are still risks of deterioration in reading literacy. One possible explanation for this would be that reading requires effort and a specific purpose most of the time. Too much time spent on social entertainment reading activities could lead to a lower level of metacognitive strategy awareness and use [59]. All these challenges can arise when they access the Internet and could explain the decline in reading literacy performance. Hence, the instruction of Internet use from home and school for educational purposes, e.g., information-seeking reading activities, as well as the teaching of basic digital reading skills has become particularly important and necessary.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Major Findings

This study aimed to investigate the overall picture in this research field using both qualitative and quantitative research methods. Notably, the top ten organizations, countries with the highest publications, author keywords, cited references, cited sources, and cited authors were visualized via VOSviewer clustering and counting techniques. Reading motivation, online reading activities, and digital reading literacy assessment tests were also explored through the visualization citation network in CitNetExplorer. The results show that reading motivation played an important role in reading literacy achievement in the context of formal schooling, while online reading activities could both positively and negatively affect reading literacy due to their multifaceted nature. The digital reading literacy assessment tests vary across the world.

7.2. Limitations of the Current Study

Due to the limited resources, the results of the current study were largely determined by the previous studies extracted from the WoS Core Collection database, which may give rise to publication bias. The year trend of publications and citations only started in 2008 would be explained by this. Besides, the publications cited in the citation network may not represent the same highlights in reading literacy. And this could lead to subjective categories of the findings, which need to be further investigated. Furthermore, the citation bias might be subject to the language’s popularity and familiarity; for example, literature written in English tended to be frequently cited. Finally, the relationship between reading motivation and achievement/reading literacy might vary between languages with different orthographic depths, which was not discussed in the current study.

7.3. Implications for Future Research

Reading is a broad field with a considerable number of research topics to explore and discuss. High reading literacy achievement is crucial not only for the development of a nation but also for individuals. Promoting the reading competence of humankind requires the efforts of generations. Therefore, there is a lot that researchers and stakeholders can do about it.

In the future, more participants of different ages, especially adults (in college or at work), can be further included and compared in reading literacy research. With these large-sample-based studies, we can attain more insights into reading competence. Similar to international reading literacy tests for adolescents, the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) is designed to evaluate the adults’ literacy level based on the previous framework, i.e., the International Adult Literacy Study (IALS), Adult Literacy and Lifeskills (ALL) Survey. Researchers can carry out in-depth studies on influential factors in this matter. For example, adult reading literacy was largely predicted by initial education, occupation, language background, and age among Nordic adults. Informal reading outside of work might provide every adult with the chance to develop and enrich their literacy skills [80]. Higher education entrance qualification through the academic track also accounted for higher reading literacy among German adults [81]. As for comparison, one aspect is for relevant longitudinal studies that can explore the changes and evolution of reading literacy performance among those young adults who have participated in the first or second PISA or PIRLS assessment cycle.

In the future, L2 reading literacy should be widely investigated. Current pioneer international tests led by IEA or OCED focus more on L1 adolescents’ reading literacy. Compared to this, relevant studies in the second language are remarkably scant. Future studies can explore the contextual factors influencing L2 reading literacy. Few studies were implemented to compare the pronounced factors that could predict reading literacy achievement among both L1 and L2 students. Predictors such as reading motivation, self-confidence, linguistic, socioeconomic status, and home and school literacy environment were disclosed as important for reading literacy development among Netherlandish pupils [21,82], and early home reading activities were essential for later L1 and L2 reading literacy achievement in primary school [83]. In addition, a general international assessment framework similar to PIRLS and PISA for L2 learners could also be explored. For adolescents, the relationship between their mother tongue and the foreign language(s) they have been learning since childhood is inseparable. High L2 reading literacy skills can enable them to learn other skills and expose themselves to more diverse cultures. Furthermore, the assessment for L2 reading literacy in print or digital forms could be developed accordingly based on specific factors, for instance, target language attributes and learners’ proficiency levels. More specifically, there is, to date, no such tests or evaluation framework for L2 Chinese reading literacy performance.

In the future, support or intervention for promoting reading literacy can be developed and further implemented. There were plenty of studies that revealed the many factors that can cast strong influences on reading literacy (print and digital) scores. For instance, external ones were identified, e.g., socioeconomic status, school, home resources, teaching strategies, and teacher assessment methods [84,85,86,87]. Recently, breakfast intake was also found essential for accounting for 10–11-year-olds’ reading literacy scores in Nordic countries [88]. Researchers can unveil more factors and investigate relevant interventions and support for them. For example, from the perspective of libraries, there was still a gap found between digital reading platforms and guiding services in university libraries in China [89]. Public libraries could also embrace the challenges of the complexity of the reading process to offer corresponding support for fostering the reading skills of children and adults [90], as well as the support for prisoners provided by prison libraries. Programs or assisting tools can be introduced, such as QRAC-the-Code, the collaboration script for boosting critical thinking and science reading literacy in the virtual environment [56]. The TuinLEC program was beneficial for sixth-graders’ reading achievements and self-efficacy [91] and the AutoTutor for improving comprehension skills in adults with low reading literacy [92].

Last but not least, future research concerning relationships between reading motivation and reading literacy should take languages into account. Namely, whether in the mother tongue or the second language orthographic depths could affect the acquisition process and the motivation in the course of learning how to read.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and Z.Y.; methodology, X.L.; software, X.L.; validation, X.L. and Z.Y.; formal analysis, X.L.; investigation, X.L.; resources, X.L.; data curation, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, X.L.; visualization, X.L.; supervision, Z.Y.; project administration, X.L.; funding acquisition, X.L. and Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and the Research Funds of Beijing Language and Culture University (22YCX050) "The comparative study of foreign reading models and their application in Chinese reading". This work is also funded by 2019 MOOC of Beijing Language and Culture University (MOOC201902) (Important) “Introduction to Linguistics”; "In-troduction to Linguistics" of online and offline mixed courses in Beijing Language and Culture University in 2020; Special fund of Beijing Co-construction Project-Research and reform of the "Undergraduate Teaching Reform and Innovation Project" of Beijing higher education in 2020-innovative "multilingual +" excellent talent training system (202010032003); The research project of Graduate Students of Beijing Language and Culture University "Xi Jinping: The Governance of China" (SJTS202108).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Beijing Language and Culture University. All researchers can provide written informed consents.

Data Availability Statement

We make sure that all data and materials support our published claims and comply with field standards.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere thanks to the anonymous review experts for their comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Main studies selected.

Table A1.

Main studies selected.

| Author | Journal | Aim | Method | Sample | Main Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becker et al., 2010 [46] | Journal of Educational Psychology | To study the longitudinal relationships of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation with reading literacy development | Qualitative; structural equation modeling | 740 students from 54 classes in 22 Berlin elementary schools | Reading amount functioned as a mediator between intrinsic reading motivation and later reading literacy. The relationship between extrinsic reading motivation and reading literacy was reciprocal. |

| Cheung et al., 2013 [93] | Asia-Pacific Education Researcher | To investigate the mediating effects of online reading activities and ICT use at school and at home on the relationships between gender and digital reading literacy | Secondary analysis, PISA 2009 student questionnaire | 4837 Hong Kong students and 4989 Korean students based on PISA 2009 database | Online reading activities and ICT use at home and school mediated the relations between gender difference and digital reading literacy in Hong Kong. |

| Chen et al., 2021 [52] | Computers & Education | To investigate the effect of social media on adolescents’ digital reading literacy and mediating effect of self-regulated learning between them | Secondary analysis; structural equation modeling | 105,430 15-year-old students from 3693 schools across six East Asian regions and nine Western countries | Social media had no direct negative effect on digital reading literacy. Small positive impacts were observed. The mediating effect of self-regulated learning varied across regions. |

| Gil et al., 2015 [67] | Computers & Education | To validate e-CompLEC test for the assessment of strategic reading literacy skills online | Mixed design, test performance, etc. | 2649 7th- and 9th-graders from 44 schools in Spain | Confirmed the reliability and validity of e-CompLEC which also provided self-regulation and reading behavior indices predictive of performance. |

| Lee & Wu, 2012 [53] | Learning and Individual Differences | To investigate the effect of individual differences in relationship between the old and new reading literacy and mediating role of online reading activities | Secondary analysis, PISA 2009 student questionnaire | 297,295 fifteen-year-old students (49.6% males) across 42 regions based on PISA 2009 database | With the mediating effect of online reading activities, students’ reading literacy improved with positive attitude toward computers, confidence, and ICT availability at home. |

| Liu & Ko, 2017 [11] | Journal of Research in Education Sciences | To review studies of the students’ online reading skills in the past two decades | A selective review | Literature from various databases | Fifth- to eighth-graders did not possess sufficient reading skills, such as web searching, evaluation, and integration abilities. |

| Park, 2011 [43] | Learning and Individual Differences | To investigate the factors underlying reading motivation and the relations between motivational factors and reading performance | Secondary analysis, PIRLS 2006 student questionnaire | 4826 students from the U.S. | Reading motivation was a strong predictor of reading performance despite its various facets. |

| Wu & Peng, 2017 [55] | Interactive Learning Environments | To investigate the effects of the electronic and print modality and online reading activities on printed and electronic reading literacy across regions | Secondary analysis, PISA 2009 | 31,784 fifteen-year-old students from 19 countries | Students achieved better print reading literacy. Information-seeking activities positively predicted reading literacy in both print and electronic reading literacy. |

| Ferrer et al., 2017 [94] | Contemporary Educational Psychology | To investigate readers’ process and answers to questions based on text availability and question format in reading comprehension | Two experiments;2x2 variable design | 74 secondary school students in Valencia | With or without text would be helpful for different discourse processes. Text availability benefited the open-ended but not the multiple-choice format. |

| Lee & Wu, 2013 [59] | Computers & Education | To study the effects of social entertainment and information-seeking activities on reading literacy based on knowledge of metacognitive strategies | Secondary analysis, structural equation modeling | 87,735 fifteen-year-old students (49.8% girls) across 15 regions in the PISA 2009 dataset | Mediated by metacognitive strategies, frequent information-seeking activities predicted better reading literacy, while social entertainment worked the opposite way. |

| Luyten, 2022 [60] | Studies in Educational Evaluation | To explore the impact of increases in online chatting | Secondary analysis | PISA 2009 and 2018 covering 63 countries | As online chatting increased, reading literacy and reading strategy awareness declined among 15-year-olds across countries. |

| McElvany et al., 2008 [95] | Zeitschrift fur Padagogische Psychologie | To investigate relationship between the development of reading literacy and intrinsic reading motivation from Grades 3 to 6 | Longitudinal comparison; curve models and panel models | 741 students from 54 different classes in 22 public and private elementary schools in Berlin | As reading literacy increased, reading motivation decreased, from Grades 3 to 6. Reading behavior mediated the indirect effect of early reading motivation on later reading literacy. |

| Retelsdorf & Moller, 2008 [96] | Zeitschrift fur Entwicklungs Psychologie und Padagogische Psychologie | To study the development of reading literacy, reading motivation, and reading self-concept in secondary school | Longitudinal analysis | 1409 students from 56 higher-, middle-, and lower-stream schools in Germany | Reading literacy growth was similar for all types of schools, and higher-stream students’ decrease in reading motivation was lower than that of middle- and lower-stream students. |

References

- Allagulov, A.M.; Godovova, E.V.; Inozemtseva, N.V.; Natochaya, E.N.; Torshina, A.V. Cross-disciplinary Analysis of the Concept, Reader’s Literacy”. Mod. J. Lang. Teach. Methods 2018, 8, 271–274. [Google Scholar]

- Rintaningrum, R. Explaining the Important Contribution of Reading Literacy to the Country’s Generations: Indonesian’s Perspectives. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2019, 5, 936–953. [Google Scholar]

- Zápotočná, O. Reading literacy in the age of digital technologies. Hum. Aff. 2016, 26, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponera, E.; Sestito, P.; Russo, P.M. The influence of reading literacy on mathematics and science achievement. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 109, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combrinck, C.; Mtsatse, N. Reading on paper or reading digitally? Reflections and implications of ePIRLS 2016 in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2019, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharuthram, S. Making a case for the teaching of reading across the curriculum in higher education. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2012, 32, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharuthram, S. The reading habits and practices of undergraduate students at a higher education institution in South Africa: A case study. Indep. J. Teach. Learn. 2017, 12, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, M.C.; Medina, E.J. A case of being the same? Australia and New Zealand’s reading in focus. Aust. J. Educ. 2020, 64, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci, J. A heuristic review at the results of the PISA tests (2000–2018): The reading skills of 15-year-olds in Mexico. Rev. CS Cienc. Soc. 2021, 34, 301–335. [Google Scholar]

- Reiber-Kuijpers, M.; Kral, M.; Meijer, P. Digital reading in a second or foreign language: A systematic literature review. Comput. Educ. 2021, 163, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, I.F.; Ko, H.W. Online Reading Research: A Selective Review. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2017, 62, 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, D.A. What happened to literacy? Historical and conceptual perspectives on literacy in UNESCO. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2011, 31, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.M.; Mullis, I.V.S.; Martin, M.O.; Trong, K.L. (Eds.) PIRLS 2006 Encyclopedia: A Guide to Reading Education in the Forty PIRLS 2006 Countries; TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College: Chestnut Hill, MA, USA, 2006; Available online: https://timss.bc.edu/pirls2006/encyclopedia.html (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- OECD. The Definition and Selection of Key Competencies: Executive Summary; OECD: Paris, France, 2005; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/document/17/0,3746,en_2649_39263238_2669073_1_1_1_1,00.html (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Mullis, I.V.S.; Martin, M.O. (Eds.) PIRLS 2021 Assessment Frameworks. 2019. Available online: https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/pirls2021/frameworks/ (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- Kell, M.; Kell, P. Global Testing: PISA, TIMSS and PIRLS. In Literacy and Language in East Asia. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects; Springer: Singapore, 2014; pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.C.; Hiebert, E.H.; Scott, J.A.; Wilkinson, I.A.G. Becoming a Nation of Readers: The Report of the Commission on Reading; National Academy of Education, National Institute of Education & Center for the Study of Reading: Washington, DC, USA, 1985; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J.T.; Wigfield, A. Engagement and motivation in reading. In Handbook of Reading Research, 3rd ed.; Kamil, M.L., Mosenthal, P.B., Pearson, P.D., Barr, R., Eds.; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 403–422. [Google Scholar]

- De Naeghel, J.; Van Keer, H.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Rosseel, Y. The Relation Between Elementary Students’ Recreational and Academic Reading Motivation, Reading Frequency, Engagement, and Comprehension: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 104, 1006–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavamnia, M.; Kashkouli, Z. Motivation, Engagement, Strategy Use, and L2 Reading Proficiency in Iranian EFL Learners: An Investigation of Relations and Predictability. Read. Psychol. 2022, 43, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netten, A.; Droop, M.; Verhoeven, L. Predictors of reading literacy for first and second language learners. Read. Writ. 2011, 24, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.H. The joint effects of reading motivation and reading anxiety on English reading comprehension: A case of Taiwanese EFL university learners. Taiwan J. TESOL 2019, 16, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pecjak, S.; Kosir, K. Reading motivation and reading efficiency in third and seventh grade pupils in relation to teachers’ activities in the classroom. Stud. Psychol. 2008, 50, 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- De Naeghel, J.; Valcke, M.; De Meyer, I.; Warlop, N.; van Braak, J.; Van Keer, H. The role of teacher behavior in adolescents’ intrinsic reading motivation. Read. Writ. 2014, 27, 1547–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElvany, N.; Becker, M.; Ludtke, O. The role of family variables in reading literacy, vocabulary, reading motivation, and reading behavior. Z. Entwickl. Padagog. Psychol. 2009, 41, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Jahan, I.; Hosen, I.; al Mamun, F.; Kaggwa, M.M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Mamun, M.A. How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Impacted Internet Use Behaviors and Facilitated Problematic Internet Use? A Bangladeshi Study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 1127–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamasak, T.; Topbas, M.; Ozen, N.; Esenulku, G.; Yildiz, N.; Sahin, S.; Arslan, E.A.; Cil, E.; Kart, P.O.; Cansu, A. An Investigation of Changing Attitudes and Behaviors and Problematic Internet Use in Children Aged 8 to 17 Years During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin. Pediatr. 2022, 61, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. PISA 2009 Assessment Framework: Key Competencies in Reading, Mathematics and Science, PISA; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maceviciute, E.; Manzuch, Z. Conceptualising the role of digital reading in social and digital inclusion. Inf. Res.-Int. Electron. J. 2018, 23. Available online: http://informationr.net/ir/23-4/isic2018/isic1805.html (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- OECD. PISA 2009 Results: Students On Line: Digital Technologies and Performance (Volume VI), PISA; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Cheng, W.; Chang, T.W.; Zheng, X.; Huang, R. A comparison of reading comprehension across paper, computer screens, and tablets: Does tablet familiarity matter? J. Comput. Educ. 2014, 1, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiel, G.; Cosgrove, J. International Assessments of Reading Literacy. Read. Teach. 2002, 55, 690–692. [Google Scholar]

- Coiro, J. Rethinking Reading Assessment in a digital Age: How is Reading Comprehension different and Where do We turn now? Educ. Leadersh. 2009, 66, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mullis, I.V.S.; Martin, M.O.; Foy, P.; Hooper, M. ePIRLS 2016 International Results in Online Informational Reading. 2017. Available online: http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/pirls2016/international-results/ (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. CitNetExplorer: A new software tool for analyzing and visualizing citation networks. J. Informetr. 2014, 8, 802–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmeron, L.; Garcia, A.; Vidal-Abarca, E. WebLEC: A test to assess adolescents’ Internet reading literacy skills. Psicothema 2018, 30, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Dong, X.; Peng, Y. Discovery of the key contextual factors relevant to the reading performance of elementary school students from 61 countries/regions: Insight from a machine learning-based approach. Read. Writ. 2022, 35, 93–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Guthrie, J.T. Modeling the effects of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, amount of reading, and past reading achievement on text comprehension between U.S. and Chinese students. Read. Res. Q. 2004, 39, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. How motivational constructs interact to predict elementary students’ reading performance: Examples from attitudes and self-concept in reading. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2011, 21, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.M.; Lam, J.W.I.; Au, D.W.H.; So, W.W.Y.; Huang, Y.L.; Tsang, H.W.H. Explaining student and home variance of Chinese reading achievement of the PIRLS 2011 Hong Kong. Psychol. Sch. 2017, 54, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Y.K. The role of attribution beliefs, motivation and strategy use in Chinese fifth-graders’ reading comprehension. Educ. Res. 2009, 51, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; McElvany, N.; Kortenbruck, M. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Reading Motivation as Predictors of Reading Literacy A Longitudinal Study. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbecker, K.; Forster, N.; Souvignier, E. Reciprocal Effects between Reading Achievement and Intrinsic and Extrinsic Reading Motivation. Sci. Stud. Read. 2019, 23, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, G.W. From reading strategy instruction to student reading achievement: The mediating role of student motivational factors. Psychol. Sch. 2019, 56, 724–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolic-Vehovec, S.; Pecjak, S.; Zubkovic, B.R. Gender differences in (meta) cognitive and motivational factors of text comprehension of adolescents in Croatia and Slovenia. Suvrem. Psihol. 2009, 12, 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- Syamsuri, A.S.; Bancong, H. Do Gender and Regional Differences Affect Students’ Reading Literacy? A Case Study in Indonesia. Eurasian J. Appl. Linguist. 2022, 8, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Coiro, J.; Dobler, E. Exploring the online reading comprehension strategies used by sixth-grade skilled readers to search for and locate information on the Internet. Read. Res. Q. 2007, 42, 214–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.P.; Lin, C.H.; Chen, G.W. A cross-cultural perspective on the relationships among social media use, self-regulated learning and adolescents’ digital reading literacy. Comput. Educ. 2021, 175, 104322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Wu, J.Y. The effect of individual differences in the inner and outer states of ICT on engagement in online reading activities and PISA 2009 reading literacy: Exploring the relationship between the old and new reading literacy. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2012, 22, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y. Gender differences in online reading engagement, metacognitive strategies, navigation skills and reading literacy. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2014, 30, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Peng, Y.C. The modality effect on reading literacy: Perspectives from students’ online reading habits, cognitive and metacognitive strategies, and web navigation skills across regions. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2017, 25, 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H. Facilitating critical thinking using the C-QRAC collaboration script: Enhancing science reading literacy in a computer-supported collaborative learning environment. Comput. Educ. 2015, 88, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.C. E-Books and Audiobooks: Extending the Digital Reading Experience. Read. Teach. 2015, 69, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmusson, M.; Aring; berg-Bengtsson, L. Does Performance in Digital Reading Relate to Computer Game Playing? A Study of Factor Structure and Gender Patterns in 15-Year-Olds’ Reading Literacy Performance. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 59, 691–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Wu, J.Y. The indirect effects of online social entertainment and information seeking activities on reading literacy. Comput. Educ. 2013, 67, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyten, H. The global rise of online chatting and its adverse effect on reading literacy. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2022, 72, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintsch, W. Comprehension: A Paradigm for Cognition; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Manez, I.; Vidal-Abarca, E.; Magliano, J.P. Comprehension processes on question-answering activities: A think-aloud study. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 20, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiro, J.; Kennedy, C. The Online Reading Comprehension Assessment (ORCA) Project: Preparing Students for Common Core Standards and 21st Century Literacies. White Paper Based on Work Supported by the United States Department of Education under Award No. R305G050154 and R305A090608. 2011. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/ (accessed on 6 November 2022).

- Caccia, M.; Giorgetti, M.; Toraldo, A.; Molteni, M.; Sarti, D.; Vernice, M.; Lorusso, M.L. ORCA.IT: A New Web-Based Tool for Assessing Online Reading, Search and Comprehension Abilities in Students Reveals Effects of Gender, School Type and Reading Ability. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, P.H.; Huang, C.J.; Yeh, Y.H.; Chang, K.L. The Development of an Online Reading Literacy Assessment. In Advanced Materials Research; Trans Tech Publications, Ltd.: Wollerau, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 838–843. [Google Scholar]

- Tatay, A.C.L.; Pelluch, L.G.; Gamez, E.V.A.; Gimenez, T.M.; Lloria, A.M.; Perez, R.G. The Reading Literacy test for Secondary Education (CompLEC). Psicothema 2011, 23, 808–817. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, L.; Martinez, T.; Vidal-Abarca, E. Online assessment of strategic reading literacy skills. Comput. Educ. 2015, 82, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.F.; Wang, H.; Chang, F.; Yi, H.M.; Shi, Y.J. Reading achievement in China’s rural primary schools: A study of three provinces. Educ. Stud. 2021, 47, 344–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, M. Cause it’s uncool when they figure out that you read books.”-On the role of peers in reading careers. Z. Soziologie Erzieh. Sozial. 2010, 30, 181–195. [Google Scholar]

- Philipp, M.; Golitz, D.; von Salisch, M. What is the Contribution of the Peer Group to the Reading Motivation of Secondary School Students? Psychol. Erzieh. Unterr. 2010, 57, 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz, M. A Study on the Reading Motivation of Elementary 3rd, 4th, and 5th Grade Students. Egit. Bilim-Educ. Sci. 2013, 38, 260–271. [Google Scholar]

- Kessels, U.; Heyder, A.; Latsch, M.; Hannover, B. How gender differences in academic engagement relate to students’ gender identity. Educ. Res. 2014, 56, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansu, P.; Regner, I.; Max, S.; Cole, P.; Nezlek, J.B.; Huguet, P. A burden for the boys: Evidence of stereotype threat in boys’ reading performance. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 65, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, H.; Kasper, D.; Trendtel, M. Assuming measurement invariance of background indicators in international comparative educational achievement studies: A challenge for the interpretation of achievement differences. Large-Scale Assess. Educ. 2017, 5, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fajardo, I.; Villalta, E.; Salmeron, L. Are really digital natives so good? Relationship between digital skills and digital reading. An. Psicol. 2016, 32, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.A.; Kamal, H.; Elkholy, H. The prevalence of problematic internet use among a sample of Egyptian adolescents and its psychiatric comorbidities. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, I.S.; Penades, R.L.; Rodriguez, R.R.; Negre, J.S. Cyberbullying and Internet Addiction in Gifted and Nongifted Teenagers. Gift. Child Q. 2020, 64, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor-Calvo, S.; Pulido-Rodriguez, C. Challenges and Risks of Internet Use by Children. How to Empower Minors? Comunicar 2012, 20, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K. Understanding Online Gaming Addiction and Treatment Issues for Adolescents. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2009, 37, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkunen, S.; Nissinen, K.; Malin, A. The role of informal learning in adults’ literacy proficiency. Eur. J. Res. Educ. Learn. Adults 2021, 12, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blossfeld, G.J.; Blossfeld, P.N.; Blossfeld, H.P. Higher Education Entry Certificate Obtained via the Traditional Academic Track and Institutions of Second-Chance Education. Adult Reading Literacy and Socioeconomic Status at Labor Market Entry. Z. Padagog. 2021, 67, 721–739. [Google Scholar]

- Netten, A.; Luyten, H.; Droop, M.; Verhoeven, L. Role of linguistic and sociocultural diversity in reading literacy achievement: A multilevel approach. J. Res. Read. 2016, 39, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.K.; Zhu, Y.; Hui, S.Y.; Ng, H.W. The effects of home reading activities during preschool and Grade 4 on children’s reading performance in Chinese and English in Hong Kong. Aust. J. Educ. 2017, 61, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Boakye, N. The efficacy of socio-affective teaching strategies in a reading intervention: Students’ views and opinions. Lang. Matters 2016, 47, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Sakyi, A.; Cui, Y. Identifying Key Contextual Factors of Digital Reading Literacy Through a Machine Learning Approach. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2022, 60, 1763–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.Q.; Johnson, R.L. Teachers’ classroom assessment practices and fourth-graders’ reading literacy achievements: An international study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 29, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirin, S.R. Socioeconomic Status and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Review of Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2005, 75, 417–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illokken, K.E.; Ruge, D.; LeBlanc, M.; Overby, N.C.; Vik, F.N. Associations between having breakfast and reading literacy achievement among Nordic primary school students. Educ. Inq. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.X.; Liu, B.; Tsai, S.B. Analysis and Research on Digital Reading Platform of Multimedia Library by Big Data Computing in Internet Era. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 5939138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhardt, H. Reading Research and Its Potential for Reading Promotion in Public Libraries. Bibl. Forsch. Prax. 2017, 41, 319–329. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Abarca, E.; Gilabert, R.; Ferrer, A.; Avila, V.; Martinez, T.; Mana, A.; Llorens, A.C.; Gil, L.; Cerdan, R.; Ramos, L.; et al. TuinLEC, an intelligent tutoring system to improve reading literacy skills. Infanc. Y Aprendiz. 2014, 37, 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Lippert, A.; Cai, Z.Q.; Chen, S.; Frijters, J.C.; Greenberg, D.; Graesser, A.C. Patterns of Adults with Low Literacy Skills Interacting with an Intelligent Tutoring System. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2022, 32, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.C.; Mak, S.K.; Sit, P.S. Online Reading Activities and ICT Use as Mediating Variables in Explaining the Gender Difference in Digital Reading Literacy: Comparing Hong Kong and Korea. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2013, 22, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, A.; Vidal-Abarca, E.; Serrano, M.A.; Gilabert, R. Impact of text availability and question format on reading comprehension processes. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElvany, N.; Kortenbruck, M.; Becker, M. Reading Literacy and Reading Motivation: Their Development and the Mediation of the Relationship by Reading Behavior. Z. Padagog. Psychol. 2008, 22, 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Retelsdorf, J.; Moller, J. Developments of reading literacy and reading motivation: Achievement gaps in secondary school? Z. Entwickl. Padagog. Psychol. 2008, 40, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).