Occupational Therapy Education and Entry-Level Practice: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection and Data Collection Process

2.4. Quality Appraisal and Data Items

2.5. Risk of Bias and Synthesis Methods

3. Results

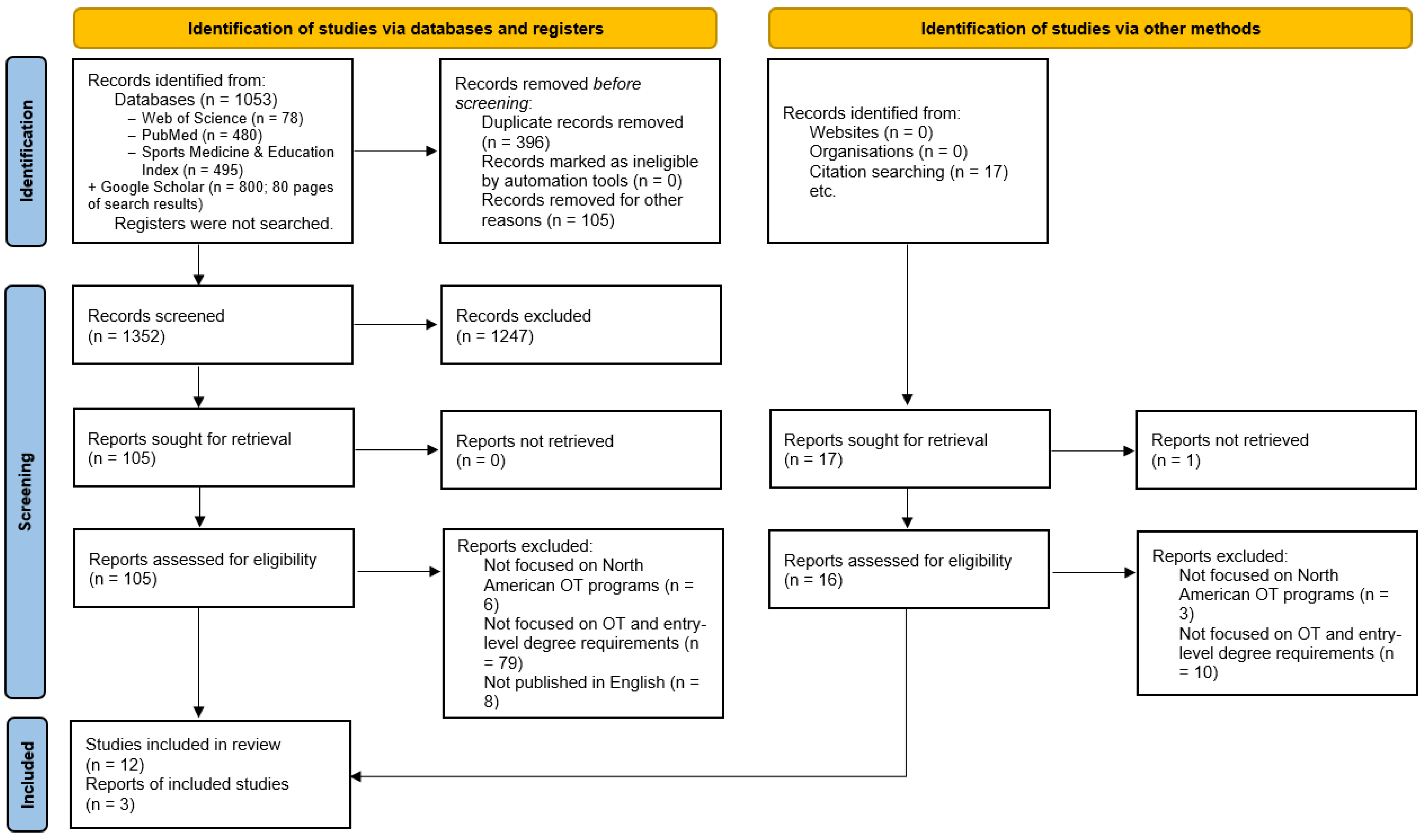

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Quality Appraisal

3.4. Risk of Bias

3.5. Thematic Areas (Results)

3.5.1. Should an Entry-Level Doctorate Be Mandated for OT Practice?

3.5.2. Arguments for Single Point of Entry

3.5.3. Arguments for Dual Points of Entry

3.6. Reflection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Article Information | Design | N | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dickerson and Trujillo [20] Published: 2009 Article type: Original | Survey (mainly quan) | 600 occupational therapists |

|

| Lucas Molitar and Nissen [21] Published: 2018 Article type: Original | Survey (quan) | 388 OT practitioners and students |

|

| McCombie [17] Published: 2016 Article type: Original | Survey (quan + qual) | 221 (144 occupational therapists; 77 OTAs) |

|

| Mineo et al. [16] Published: 2018 Article type: Original | Survey (quan + qual) | 53 OT faculty |

|

| Muir [13] Published: 2016Article type: Dissertation | Case studies through semi-structured interviews | 14 supervisors |

|

| Ozelie et al. [14] Published: 2020 Article type: Original | Retrospective cohort design | 213 students |

|

| Ruppert [18] Published: 2017 Article type: Original;Capstone Project | Survey (quan; cohort study) | 52 OT program directors |

|

| Smallfield et al. [19] Published: 2019 Article type: Original | Survey (quan) | 208 OT graduates |

|

| Article Information | Design/Article Type | Main Suggestions/Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Brown et al. [25] Published: 2015 | Commentary |

|

| Brown et al. [24] Published: 2015 | Commentary |

|

| Brown et al. [15] Published: 2016 | Overview |

|

| Case-Smith et al. [23] Published: 2014 | Commentary |

|

| Coppard et al. [26] Published: 2009 | Perspective/Opinion |

|

| Fisher and Crabtree [27] Published: 2009 | Commentary (general cohort theory) |

|

| Wells and Crabtree [4] Published: 2012 | Overview/Exploratory review |

|

References

- Schools. Available online: https://acoteonline.org/all-schools/ (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- About AOTA. Available online: https://www.aota.org/AboutAOTA.aspx (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Qualifications of an Occupational Therapist. Available online: https://www.aota.org/Education-Careers/Advance-Career/Qualifications.aspx (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Wells, J.K.; Crabtree, J.L. Trends Affecting Entry Level Occupational Therapy Education in the United States of America and Their Probable Global Impact. Indian J. Occup. Ther. 2012, 44, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- OT Doctorate and OTA Bachelor’s Mandates: Updates, Background, and Resources. Available online: https://www.aota.org/Education-Careers/entry-level-mandate-doctorate-bachelors.aspx (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Joint AOTA-ACOTE Statement on Entry-Level Education. Available online: https://www.aota.org/AboutAOTA/Get-Involved/BOD/News/2019/Joint-AOTA-ACOTE-Statement-Entry-Level-Education-April-2019.aspx (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- History of AOTA Accreditation. Available online: https://www.aota.org/education-careers/accreditation/overview/history.aspx (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Entry Level Education in Occupational Therapy. Available online: http://caot.in1touch.org/uploaded/web/Accreditation/entry_level%20jc_gb2%20jc.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Occupational Therapists. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/occupational-therapists.htm (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderson, S.; Tatt, I.D.; Higgins, J.P.T. Tools for Assessing Quality and Susceptibility to Bias in Observational Studies in Epidemiology: A Systematic Review and Annotated Bibliography. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 36, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Version 2018; Registration of Copyright (#1148552); Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada: Québec, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, S.L. Supervisor Perceptions of Entry-Level Doctorate and Master’s of Occupational Therapy Degrees. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ozelie, R.; Burks, K.A.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Riggilo, K.; Sivak, M. Masters to Doctorate: Impact of the Transition on One Occupational Therapy Program. J. Occup. Ther. Educ. 2020, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Crabtree, J.L.; Wells, J.; Mu, K. The Entry-Level Occupational Therapy Clinical Doctorate: The Next Education Wave of Change in Canada? Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2016, 83, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mineo, B.; Hathaway, B.; Kadkade, M. International Occupational Therapy Faculty Perceptions Regarding Doctoral Level Education. Open J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombie, R.P. Entry-Level Doctorate for Occupational Therapists: An Assessment of Attitudes of Occupational Therapists and Occupational Therapy Assistants. Rehab. Res. Policy Educ. 2016, 30, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppert, T.N. Status of the Entry-Level Clinical Doctorate in Occupational Therapy Education. Doctor of Occupational Therapy Capstone Projects. 2017. Paper 4. Available online: http://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/smhs_crl_capstones/4?utm_source=hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu%2Fsmhs_crl_capstones%2F4&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Smallfield, S.; Flanigan, L.; Sherman, A. Comparing Outcomes of Entry-Level Degrees from One Occupational Therapy Program. J. Occup. Ther. Educ. 2019, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, A.E.; Trujillo, L. Practitioners’ Perceptions of the Occupational Therapy Clinical Doctorate. J Allied Health 2009, 38, e47–e53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lucas Molitor, W.M.; Nissen, R. Clinician, Educator, and Student Perceptions of the Entry-Level Academic Degree Requirements in Occupational Therapy Education. J. Occup. Ther. Educ. 2018, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- AOTA Board of Directors Position Statement on Entry-Level Degree for the Occupational Therapist. Available online: https://www.aota.org/AboutAOTA/Get-Involved/BOD/OTD-Statement.aspx (accessed on 24 December 2021).

- Case-Smith, J.; Page, S.J.; Darragh, A.; Rybski, M.; Cleary, D. The Professional Occupational Therapy Doctoral Degree: Why Do It? Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2014, 68, e55–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.; Crabtree, J.L.; Mu, K.; Wells, J. The Entry-Level Occupational Therapy Clinical Doctorate: Advantages, Challenges, and International Issues to Consider. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2015, 29, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.; Crabtree, J.L.; Mu, K.; Wells, J. The Next Paradigm Shift in Occupational Therapy Education: The Move to the Entry-Level Clinical Doctorate. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 69 (Suppl. S2), 6912360020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppard, B.; Berthelette, M.; Gaffney, D.; Muir, S.; Reitz, S.M.; Slater, D.Y. Why Continue 2 Points of Entry Education for Occupational Therapists? OT Pract. 2009, 14, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, T.F.; Crabtree, J.L. Generational Cohort Theory: Have We Overlooked an Important Aspect of the Entry-Level Occupational Therapy Doctorate Debate? Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2009, 63, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggeri, K.; van der Linden, S.; Wang, Y.C.; Papa, F.; Riesch, J.; Green, J. Standards for Evidence in Policy Decision-Making. Nat. Res. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2020, 399005. Available online: https://go.nature.com/2zdTQIs (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Clement, D. Impact of the Clinical Doctorate from an Allied Health Perspective. AANA J. 2005, 73, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Database | Search Queries Used |

|---|---|

| Web of Science | occupational therapy AND clinical doctorate; occupational therapy AND doctorate; entry-level occupational therapy AND doctorate; entry-level occupational therapy AND clinical doctorate; occupational therapy doctorate AND perceptions; occupational therapy doctorate AND united states; occupational therapy doctorate AND Canada; occupational therapy AND doctoral; occupational therapy AND clinical doctoral; occupational therapy AND postbaccalaureate; occupational therapy AND OTD |

| PubMed | occupational therapy clinical doctorate perceptions; occupational therapy doctorate perceptions; occupational therapy doctorate [Title/Abstract]); occupational therapy clinical doctorate [Title/Abstract]; occupational therapy OTD perceptions; occupational therapy [Title/Abstract] AND debate [Title/Abstract]; occupational therapy [Title/Abstract] AND entry-level doctorate [Title/Abstract]; occupational therapy [Title/Abstract] AND OTD [Title/Abstract]; occupational therapy OTD |

| Sports Medicine and Education Index | occupational therapy AND clinical doctorate; occupational therapist attitudes AND doctorate; occupational therapist perceptions of clinical doctorate; occupational therapy OTD; occupational therapy future NOT physical; “occupational therapy” AND “doctorate” |

| Google Scholar | occupational therapy AND clinical doctorate; entry-level occupational therapy doctorate; perceptions OR attitudes of occupational therapy doctorate; occupational therapy doctorate OTD; occupational therapy AND debate; occupational therapy doctorate AND occupational therapy masters program; occupational therapy masters program; entry-level OTD |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lemez, S.; Jimenez, D. Occupational Therapy Education and Entry-Level Practice: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12070431

Lemez S, Jimenez D. Occupational Therapy Education and Entry-Level Practice: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(7):431. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12070431

Chicago/Turabian StyleLemez, Srdjan, and Dominic Jimenez. 2022. "Occupational Therapy Education and Entry-Level Practice: A Systematic Review" Education Sciences 12, no. 7: 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12070431

APA StyleLemez, S., & Jimenez, D. (2022). Occupational Therapy Education and Entry-Level Practice: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences, 12(7), 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12070431