1. Introduction

All over Europe, the rapidly increasing number of newly arrived migrant students (NAMS) not only transformed countries into ethnically diverse societies but also led to various challenges for the educational system in general and its schools and teachers in particular [

1]. In all countries, policymakers attempt to support NAMS’ integration in schools, but the concrete implementation of these attempts differ significantly. A recent Eurydice report [

2] noted that some countries prefer an immersive system where students are immediately integrated into mainstream classes (e.g., Czechia, Scotland, Montenegro). Instead, other countries opt for preparatory classes where some students—who have scarce skills in the language of instruction—receive education and targeted support separately from their native peers (e.g., Poland and Liechtenstein). Other countries choose a middle ground. Servia, for example, organizes most lessons for their NAMS in mainstream classes and some in preparatory classes. In France, students are mainly in preparatory classes and take some classes (e.g., physical education or arts) together with their native peers.

In Flanders, which is the topic of this paper, NAMS are identified as first-generation, foreign-born migrants up to 18 years of age who are obliged to enter the formal educational system. The group of NAMS includes refugees, asylum seekers, unaccompanied minors and minor foreign-speaking newcomers who have migrated to Flanders under the EU Freedom of Movement Framework for family reunification, their parents’ profession, or other reasons [

3,

4]. All minors between five and eighteen years of age living in Flanders are subject to compulsory education; this is also true for NAMS regardless of their legal status. After NAMS are listed in the national registry, foreigner’s registry, or waiting registry for asylum seekers, they have 60 days to start compulsory education. For this, there are two options. The first is to be home schooled, as in Flanders compulsory education is not equal to compulsory schooling. The second is to enroll in a school organizing compulsory education. Minor NAMS both with and without official residence documents have the right to follow lessons in a school of their choice. Flemish schools can in no way decline registration proposals of NAMS based on their legal status [

5].

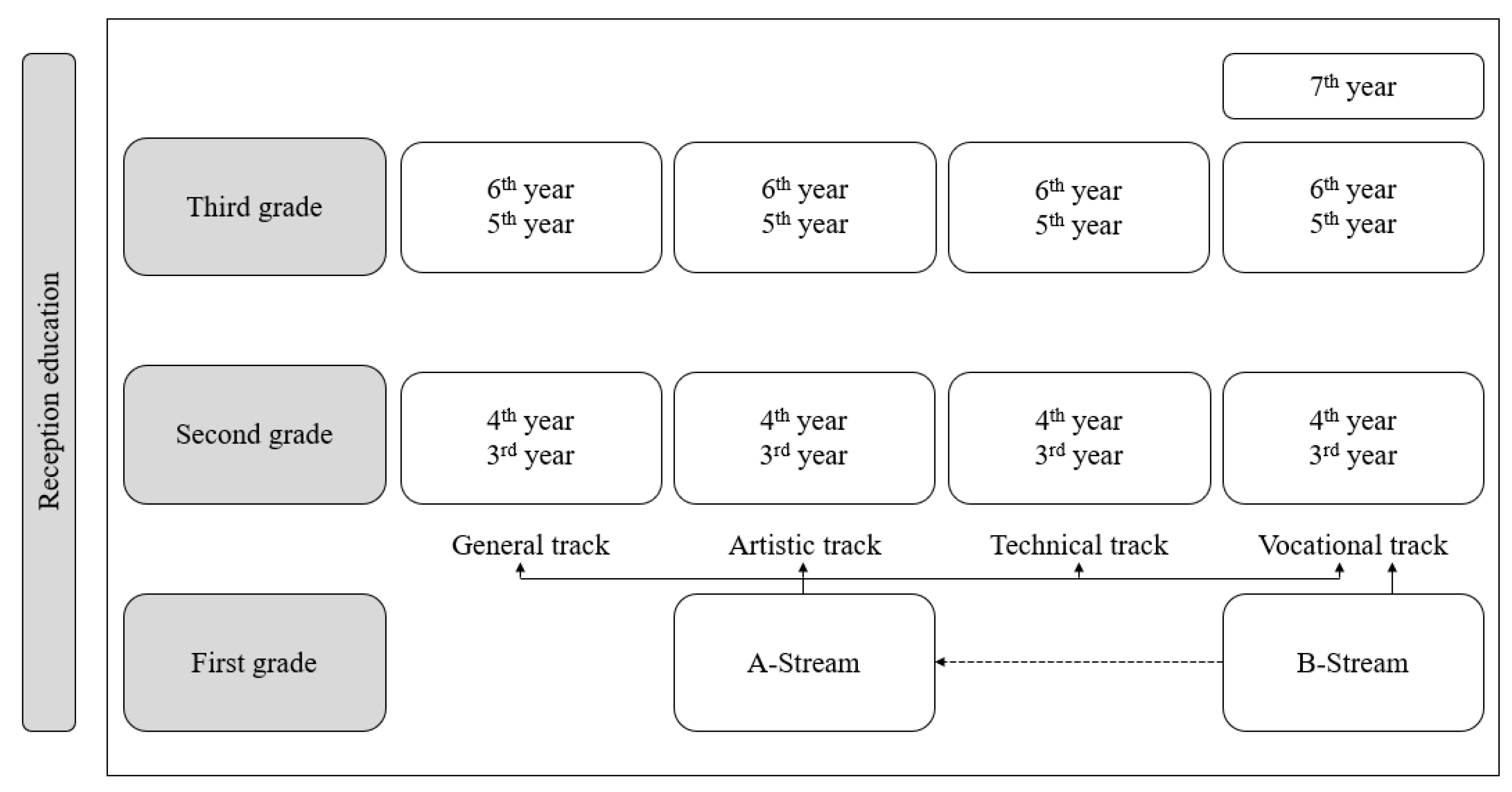

For NAMS in Flanders, the primary education system is immersive. Students are placed in mainstream classes for all lessons (though schools can arrange language immersion classes for one year). In secondary education, a preparatory system is in motion. NAMS enroll in preparatory classes to learn the Dutch language and prepare them for partaking in mainstream secondary education [

6]. In a European report entitled ‘Study on educational support for newly arrived migrant children’ [

7]—in which multiple countries were categorized in five different educational support models according to their characteristics concerning reception education—Flanders’ reception system in secondary education is classified as a compensatory support model. In such a model, strong emphasis is placed on acquiring the host country’s language during separate reception classes to get NAMS into mainstream education as quickly as possible. Put differently, compensatory measures for NAMS are taken to incorporate them into the existing system without making any significant adjustments to the system itself. In sociological terms, on the continuum between assimilation and integration, Flemish secondary education is positioned closest to the former. Through reception education, efforts are made to place NAMS on the same level as native minor citizens, instead of putting the focus on maintaining their own culture, valuing NAMS’ mother tongues, or stimulating inter-cultural contact in educational settings [

8,

9]. The Flemish language policy in schools is a good example hereof. Even though there is a growing body of Flemish, empirical research in favor of bilingualism and multilingualism, NAMS are being pressured by the government and schools to shed their mother tongues [

10,

11]. In fact, the beliefs of Flemish teachers, school directors, and the government have a rather monolinguistic character [

12].

The assimilative character of the education system (for NAMS) is also apparent in the early ability tracking that is used in Flanders: students are separated into groups based on their academic ability. In practice, NAMS are proportionally more present in ‘less prestigious’ educational tracks in comparison to their native counterparts. This system encourages inequality between NAMS and mainstream students; the minority individuals are expected to achieve the same ideal level as the majority population. Inequality between NAMS and mainstream students has taken on large proportions in Flanders. Compared to other regions and countries, international data from the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) even show that the educational system in Flanders creates one of the highest achievement gaps between native students and students with a migration background [

13,

14]. The major inequality between native and non-native students in Flanders, fueled by early ability tracking as well as extensive freedom of education (see later), makes secondary education in Flanders an interesting context to explore.

In focusing on this context of secondary education for NAMS in Flanders, some pressing limitations can be distinguished, such as a limited exchange of teaching material and good practices between schools and teachers [

15], little interaction between teachers in reception education and mainstream education [

15], and an overrepresentation of NAMS in vocational education [

16]. The central thesis of this paper is that building up networks between the actors involved in the education for NAMS may offer a solution for much of the formulated critiques. In this respect, with this paper, we set out to critically discuss the current problems education for NAMS in Flanders is experiencing and propose some first ideas for a future agenda, riddled with network-related opportunities for all actors involved. In doing so, this work aims to generate fresh insight into education for NAMS in Flanders (and, in extension, all education systems in similar positions) by linking its critiques and shortcomings to the strength of building up networks and collaboration or, put differently, connecting the dots.

If we want to understand the network opportunities for the actors involved with the education for NAMS, we first need to elaborate on the specific characteristics of the educational system the students will be integrated into. Schools and teachers are embedded in the institutional context of their school system and culture, which impacts their relative position in the educational field and their place in the social network of (educational) actors. Therefore, we will first introduce the specificities of mainstream education in Flanders, and we will elaborate on the reception education classes organized in function of the integration of NAMS. In the latter, we will also discuss the different actors involved in this process and the critical points on which they currently lack support. Next, we will build up an argumentation for social networks as a potential solution for the critiques, followed by an overview of concrete network opportunities. The paper concludes with some critical remarks.

3. Discussion—Exploring Social Networks as a Keyword in the Future Agenda for Education for NAMS

While integration is seen as the ‘ideal’ response to diversity in multicultural societies [

8], the basic rationale of the Flemish educational system set up for NAMS between the ages of twelve and eighteen years leans more towards the idea of assimilation. To this day, at the beginning of their educational career in Flanders, NAMS are segregated from their native-born peers in light of language and integration classes. Nevertheless, various studies report alarming results when it comes to the school careers of (ex-)NAMS; results that seem to be directly attributable to the assimilative character of the Flemish system of reception education. In comparison with their Dutch-speaking classmates, NAMS more often must repeat school years, drop out of school, or change their initially chosen study program. To overcome these challenges, there is growing Flemish research advocating the importance of more inclusive learning environments (e.g., [

15,

33]). Instead of a one-size-fits-all educational model in which all non-native students are expected to find their place, the importance of differentiation is increasingly highlighted to meet the diverse needs of the very heterogeneous NAMS group. Differentiation, which can be defined as applying strategies to provide maximum development opportunities for all students, can exist in multiple formats, such as providing students with tailor-made exercises, setting up peer tutoring activities, using various media throughout classes to anticipate auditory, visual, and kinesthetic learners, and applying specific assessment measures [

33]. In theory, differentiation can lead to more inclusive learning environments, in which NAMS should no longer be separated from their native-born peers. The question is, however: ‘Will this theoretical advice find its way into the Flemish educational practice?’. The role of social networks in the implementation of educational innovations has already been emphasized in the past [

40]. However, this manuscript proved that there are necessary connections missing between the actors involved in the education of NAMS. In what follows, the strength of social networks is discussed, followed by concrete network-related suggestions that may benefit reception education.

3.1. The Strength of Social Networks

The previous sections of the manuscript illustrate that multiple actors are involved in the education for NAMS in Flanders, but that there is a lack of thorough connections between these actors, resulting in rather fragmented support for NAMS. In particular, the above shows that little interaction exists between teachers in reception education and mainstream education, which makes the transition to the latter difficult. Additionally, there are voices stating that the exchange of good practices and teaching material for reception education is scarce, that there is still work to be done when it comes to (ex-)NAMS students’ relationships with both their teachers in mainstream education as well as their native peers, that NAMS’ parents should be more involved in their child’s educational career, and that there is a lack of cooperation between follow-up coaches and staff at pupil guidance centers. Moreover, there is also an overrepresentation of NAMS in vocation education due to—among other reasons—the lack of an extensive social network of people that can guide these students in their study choices, and little to no support exists for schools as well as teachers to organize education for the group of (ex-)NAMS. By creating connections between the involved actors, support can be offered in a more coherent and efficient way, and many of the above-mentioned challenges could be tackled. The social network literature can be of use here, as this offers us specific concepts to articulate how the connections between the actors could be forged—or to use network lingo—how we could connect the dots. In what follows, some basic network concepts are delineated. In a next step, these basic network concepts are then used in relation to many of the challenges that we have mentioned above.

A first important network concept in this article is

social capital. Following Bourdieu [

41], social capital are potential resources embedded in the relationships (or also called ‘ties’) between people. Applied to the topic of this article, this means that the relationships between all actors involved in the education for NAMS are conduits for the distribution of e.g., information, advice and support [

42]. Concretely, by connecting to others, a person—for example a NAM student—can receive resources he or she otherwise does not have access to. This brings us to a second important network concept, namely

relational agency. This concept describes the agency a person exerts to forge those relationships, or put differently, is about purposefully connecting to others [

43]. In other words, if individuals are looking for information to solve an issue, they can choose to actively reach out to other individuals who have the expertise they need. The idea is that social capital is built through actively forging ties with significant others [

44]. Not surprisingly, research has shown that people mostly connect to people that are similar to themselves, which is a third important network concept called

homophily [

45]. This is linked to the persistent segregation in Flanders and what Ravn et al. [

4] stated, namely that “newcomers (and other migrant students) and native students seem to be living in two separate worlds”. Network literature, however, has persistently demonstrated that having contacts with diverse people is crucial, as this brings in new perspectives and innovative ideas [

46]. Getting into contact with people that are different from a person is no easy job. That is where

brokerage can play an important role. A broker is a person that forms a so-called bridge between two otherwise unconnected groups of people [

47]. Specifically, this person can function as a gateway for flows of relevant information between these groups of people.

3.2. A Future Agenda for Education for NAMS

In this section, each of the aforementioned central network concepts are applied to formulate suggestions for the future practice, research and policy agenda for Flemish secondary education for NAMS. Inspired by the reference framework for educational sciences developed by Valcke [

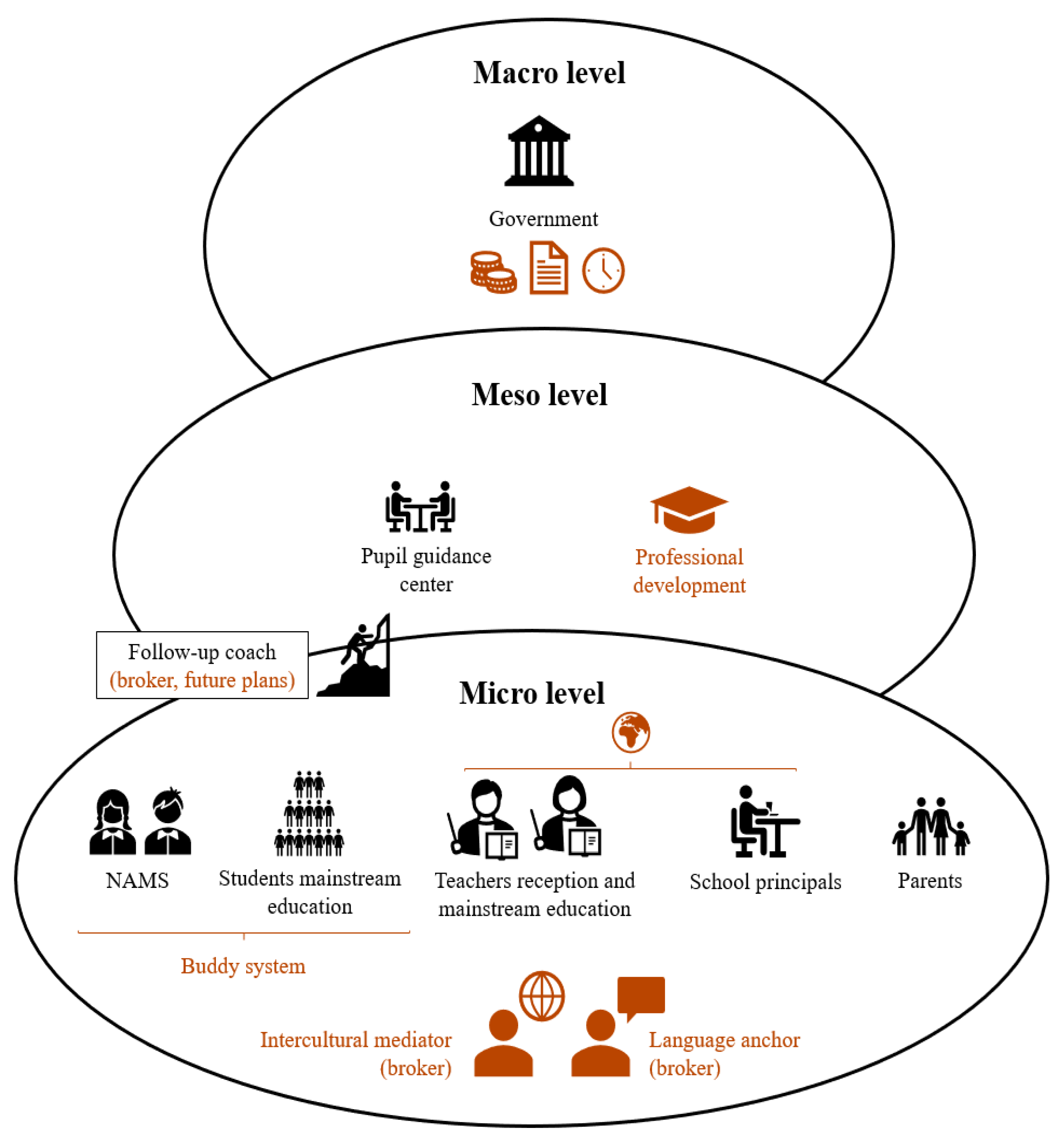

48], a distinction is made between potential initiatives at micro, meso and macro level (

Figure 2). The visualization shows an overview of all current actors (in black) that are involved in the organization of education for NAMS. A detailed description of their roles and associated challenges were addressed earlier in this manuscript. The colored elements of the visualization are the focus of interest in this discussion. In particular, these colored elements represent network-related initiatives to optimize education for NAMS. The red thread throughout all of these network-related initiatives is the mechanism of social capital, where we see ties connecting people as important sources of necessary information, advice, and support [

42]. Some of the initiatives are based on the network concept of homophily, while others are inspired by the network concepts of relational agency or brokerage.

3.2.1. Network-Related Initiatives on Micro Level

Buddy system. A first potential initiative on micro level is the introduction of a buddy system between NAM and ex-NAM students. Generally stated, applying a buddy system in a school means that a pupil gets paired up with another pupil in order to promote friendship and provide aid with coursework, but also helping them to feel a greater sense of belonging as well as creating a more inclusive school community [

49]. Ex-NAMS have recently undergone a similar (educational) trajectory and thus can exchange experiences as so-called role-models. The mechanism of homophily—connecting to others with similar characteristics—is clearly at play here. However, not only ex-NAMS, but also mainstream similar-age students can be encouraged to act as buddies/mentors. These students are similar to the NAM students when it comes to age but can bring them into contact with new perspectives and innovative ideas as they have other backgrounds and educational trajectories. Kemper et al. [

1] have shown, however, that at present this practice is still seldomly applied in Flanders.

Teacher-pupil relationship. Next to student-student ties, initiatives could also be undertaken with respect to the teacher-pupil relationship. Previous research in Flanders has shown that in vocational education especially, ethnic minority students report rather negative relationships with their teachers. Sometimes these relationships are even mortgaged by stereotype threat or ethnic victimization [

18,

36]. From a social network perspective and, particularly, the idea of homophily, this finding could be explained by the fact that teachers with migration backgrounds are very scarce in Flanders. About 5% of our teachers have a migration background, but most of them have their roots in neighboring countries such as the Netherlands and France. Less than 1% have non-western roots, for example in Morocco, Turkey or Congo. The lack of an ethnically diverse school team is a shortcoming, as international research shows that when non-native pupils recognize themselves in a teacher, they perform better and the risk of dropping out is reduced [

50].

A first action school leaders can undertake to achieve more ethnically diverse school teams is to set particular targets in which they aim to increase the percentage of personnel with a non-western migration background within a certain time frame [

50]. Aside from this rather straightforward action, school leaders could also introduce brokers in the school team—or so-called bridge figures. Imagine, for example, the inclusion of language anchors [

2]. Emery et al. (forthcoming) found that the absence of language support in mainstream education is one of the main reasons why the transition of NAMS from reception to mainstream education is experienced as difficult. The vast majority of Flemish teachers (77.3%) support the idea of the exclusive legitimacy of the Dutch language in education, which is often registered in policies of Flemish schools too. The stronger these monolingual beliefs, the lower teachers’ trust in the academic engagement of students, which is detrimental to the teacher-student relationship [

11].

A language anchor’s duties may consist of three parts. First, a language anchor can be appointed to—in cooperation with the entire school team—work out alternative frameworks and policies that replace the current, monolingual practices for a multilingual vision. Second, as teachers are often unqualified to teach a diverse group of multilingual pupils [

11], language anchors as experts in language sensitive teaching can function as contact points for teachers and follow-up coaches. Third, this person can offer a listening ear to any ex-NAM who is struggling with the Dutch language. In consultation with the follow-up coach, for every individual pupil, concrete linguistic actions could be included in a personal trajectory.

In addition to language anchors, school principals may also consider other bridge figures, such as intercultural mediators [

38]. In connection with the large number of unaccompanied immigrant children in Sweden during the European refugee crisis, Popov and Sturesson [

51] conducted a study on the preparedness of teachers to deal with students with a migration background. The study showed that teachers did not have appropriate practical tools to deal with the cultural and linguistic gaps that are present when working with immigrant children. It therefore seems that the role of intercultural mediators in a school environment—as pitched in the Swedish work of Popov and Sturesson [

51]—is an interesting avenue to explore. An intercultural mediator can promote reciprocal understanding between NAMS, their parents and their teachers by helping immigrant pupils with language as well as the values, traditions, and culture of their new home country. In sum, intercultural mediators can operate as interpreters, support persons, or promotors and in so doing create positive relationships as well as act as brokers in the school community. In Flanders too, research shows that teachers without a migration background try to be sensitive to cultural issues, but that they lack crucial intercultural competences [

11,

52]. For example, by analyzing teacher-parents interactions related to study choices of pupils, Seghers et al. [

19] showed that migrant parents more often than Flemish middle-class parents failed to extract the information they need or desire. Teachers seem to have difficulty in better informing less knowledgeable (e.g., solid knowledge about the complex Flemish educational context) and less proactive parents about the future educational trajectory of their children. In this respect, in Flanders too, intercultural mediation seems valuable.

3.2.2. Network-Related Initiatives on Meso Level

Personal futures planning. “Personal futures planning” is a strategy in which a network of supporting figures is built up around an individual with a certain support need, with the ultimate aim to increase that individual’s quality of life [

53,

54]. Particularly, the network (of which the central individual is evidently part) regularly comes together to discuss what the desired and valuable future of the individual entails and who and what is needed to make those plans a reality [

53]. In Flanders, a non-profit organization called “Lus”, for example, employs this strategy. They are supported by the Department of Welfare, Public Health and Family which makes the service provided by the non-profit organization free of charge. The strategy of personal futures planning has already been used for a wide variety of target groups, such as individuals with a mental disability and people with emotional and behavioral difficulties, but also in the context of family support [

53]. We see merit in employing this strategy in the context of NAMS and their educational trajectories. Concretely, physical networks could be forged around NAMS—regularly meeting one another in a neutral and safe location—discussing their (educational) future and the necessary steps to be undertaken. Apart from the pupil in question, the network could consist of, for example, parents, the school principal, teachers, follow-up coaches and involved people from pupil guidance centers. In this very diverse network, new perspectives and innovative ideas can come to life [

46]. Moreover, pupils’ relational agency—and in extension the relational agency of all actors involved—could be positively impacted by literally diminishing the physical distance between them (e.g., [

55]).

Professionalization of teachers. Another initiative on the meso level could be to strengthen the professionalization of teachers. Providing equal opportunities to all pupils, including those from ethnic backgrounds, requires high-quality teachers and high-quality teacher training programs [

56]. In the context of the TALIS (i.e., Teaching and Learning International Survey), 3118 Flemish first-grade secondary school teachers were questioned about teaching in a multicultural or multilingual educational setting. While 34% of these teachers stated that this topic was addressed in their teacher training program, only half of them (17%) indicated to feel well to very well prepared to teach in a multicultural or multilingual educational setting once they entered the profession [

57].

Besides an appeal to invest in expertise regarding teaching (ex-)NAMS, Flemish teacher training programs and other professional development providers should be encouraged to stimulate the network intentionality and, by extension, the relational agency of future, beginning and experienced teachers. In a Flemish higher education setting, Van Waes et al. [

58] organized network training sessions in which teachers e.g., discussed evidence-based insights about the potential of a network and uncovered the strengths and weaknesses of their own professional networks. They uncovered that these network training sessions led to teachers having not only larger networks but also networks that were more diverse (i.e., consisted of more diverse profiles of people). Moreover, teachers also had increased access to teaching content present in the larger network of the higher education institution. This research of Van Waes et al. [

58] shows that network intentionality can be stimulated. Teachers with high levels of network intentionality—who purposefully shape their network by for example actively reaching out to others for educational matters—have more access to network resources [

40], which can be extremely useful when teaching in a multicultural setting.

3.2.3. Network-Related Initiatives on Macro Level

Finally, on a macro level, the government could also undertake action. Since NAMS comprise only about 1% of the entire secondary school pupil population per school year [

23], there is a risk that they are not a priority group at government level. Admittedly, this group is small, but their needs are high and, in the meantime, the portion of ex-NAM students who are currently enrolled in mainstream education is increasing. In this respect, the conceptual framework of ‘nested contexts of reception’ suggested by Golash-Boza and Valdez [

59] shows that national and local policies can have an impact on the education for, and educational experiences of, NAMS. In Flanders, based on the national regulation regarding compulsory education for all minors—regardless of their legal status—education is a constitutional right. All NAMS, both with and without residence documents can enroll themselves in a Flemish school [

5]. Notwithstanding this national law, the educational experiences of NAMS can differ significantly dependent on the school in which they reside. The Belgian Constitution guarantees ‘freedom of education’, which in practice means a high degree of autonomy for schools (see earlier in this manuscript). Aside from having to reach the development objectives set by the government, each school can draw up their own system of reception education. In practice, the majority of schools group NAMS according to their capacities in so-called ability groups. Schools can, however, choose to experiment with other educational practices if they notice that a certain system is not successful [

1]. When these experiments result in good practices, strong and effective social networks can help in disseminating these innovative strategies, test them in other schools and potentially impact national policy.

In summary, the autonomy of schools in Flanders leads to schools that set up innovative and interesting educational approaches for NAMS, but also to schools that are way less invested in reception education—sometimes even leaving their students to their own devices. We believe that connecting the dots between institutions could result in schools learning from one another’s good practices. However, we also acknowledge that next to setting up networks, efforts at government level—in the form of money, time, and more concrete policies—are necessary to stimulate change.

4. Some Final Critical Remarks and Implications

Finally, some critical remarks should be considered. First, in discussing the Flemish educational system, we referred to the difference in prestige when it comes to academical versus vocational tracks. The Eurobarometer poll (no. 75.4, June 2011, in [

60]) found that indeed a considerable part of the population in Flanders has a rather negative image of vocational education, particularly with respect to status. Notwithstanding these results, the vast majority of the poll’s participants did agree that vocational education largely contributes to the economy in Flanders and delivers craftsmen that are necessitous in the labor market. In this respect, we want to emphasize that we do not want to state that the overrepresentation of NAMS in vocational education is problematic in itself. We do see the high percentage of NAMS in vocational tracks as problematic because of its imbalance with the much lower percentage of native speakers in vocational education.

Second, in the manuscript we have highlighted the inequality NAMS are confronted with in Flemish education (think about the overrepresentation of NAMS in vocational tracks which are seen as less prestigious and the focus on the Dutch language providing NAMS with a great disadvantage when it comes to academic ambitions). However, the inequality NAMS are experiencing goes beyond school gates. They are dealing with other manifestations of inequality as well, such as racism and Islamophobia. Up until now, only professional networks were discussed in this manuscript. Within the school walls, connections between NAMS and their peers can be forged, but this does not guarantee NAMS feeling a sense of belonginess in the larger society. Investing in personal networks for NAMS could be profitable. In this respect, we briefly want to stress the importance of non-profit organizations that invest in involving NAMS in leisure activities as well as providing them with a voice in their neighborhood (for example, the non-profit organization “vzw Jong”). We do acknowledge that beyond networking, other actions also must be undertaken to deal with inequality, such as making people aware of their prejudices and critically and positively changing these to create an inclusive environment for all.

Third, as discussed previously, teachers feel ill-prepared to teach in multicultural and multilingual educational settings [

57]; particularly teachers lack crucial intercultural competences to deal with students with a migration background [

11,

52]. In line with Pastori et al. [

61], intercultural competences are seen as a framework consisting of interrelated knowledge, values, attitudes, skills, and action. As described in Romijn et al. [

62], the knowledge part of the abovementioned set refers to, for example, knowledge of language, culture, and religion. Furthermore, the values refer to one’s ideas regarding, for instance, inclusion and diversity, and attitudes pertain to, for example, respect and openness to other people’s beliefs and views. Finally, with respect to skills, this framework points to, for instance, being able to critically reflect on one’s own personal biases, and the actions involve behaviors striving for collective wellbeing and sustainable development. The lack of intercultural competences for teachers raises the call for appropriate professional development both for student-teachers and in-service teachers. A recent review study of Romijn et al. [

62] on the effectiveness of professional development efforts to enhance (student-)teachers’ intercultural competences indicates that three elements are of the utmost importance. First, the professional development initiative for intercultural competences should be well embedded within the organization and context of the teacher, meaning that the initiative should start from a needs assessment of the teacher and the context in which they work. In particular, the intervention should be aligned with the needs and characteristics of the local context (i.e., taking into account the characteristics of the pupil population, a school’s resources, the school policy). Key figures in the organization, such as the principal, should also be included in the intervention to ensure that the teacher can implement the intercultural strategies in practice. Second, guided critical reflection is a crucial component if the initiative aims to be effective. In particular, the intervention should include guiding sessions to support the active reflection on teachers’ belief system (regarding issues such as culturally responsive teaching, cultural biases…). Third, as teachers’ beliefs and how they act on their beliefs are not always aligned, opportunities for them to enact on the changes in their belief system and offering support for this enactment should be present.

Next to investing in teachers’ professional development (and in particular, intercultural competences), a central actor working on school level supporting NAMS, teachers, and parents is also desirable. A so-called intercultural mediator can take on the role of support person and interpreter to increase learning of all actors involved (see earlier in the manuscript). Learning, however, does not only take place in educational contexts; connections with peers, for example, both in- and outside the school are also highly valuable [

51]. In this respect, an intercultural mediator can strengthen NAMS’ learning further by being an important lever for social inclusion.

Fourth, this manuscript has discussed potential network-related initiatives that may work in the Flemish educational system. Important to emphasize is that interventions in one educational culture do not necessarily work in another context. Countries can serve as inspiration sources for each other, such as the above-mentioned proposal of intercultural mediation in the Flemish educational culture derived from the Swedish educational system. In turn, this manuscript including network-stimulating initiatives in the context of education for (ex-)NAMS may also inspire non-Flemish practitioners, researchers, and policy makers. Herewith, the specificities of a context’s own educational culture must always be kept in mind.

Continuing this cross-country perspective, we also see merit in working on supra-national-level (next to the micro-level, meso-level, and macro-level initiatives we have already proposed). We could, for example, across borders, exchange good practices in working with migrant students and provide each other with advice regarding challenges we are experiencing and the potential solutions at play. Currently, a team of researchers from Scotland, Finland and Sweden is working on an international project (TEAMS-project) in which they perform a comparative study on the barriers and opportunities for migrant integration in schools. Their aim is to work closely together and create tools and practices that can be used throughout the three participating countries. This project seems a good example of future international collaborations, which could enrich current practices all over Europe. By connecting the dots on an international level too, we can make use of a myriad of potential sources to improve education for NAMS.

Fifth, our manuscript has shown that the actors (or dots) involved in the network of education for (ex-)NAMS often act isolated from one another. With the support of the suggested network initiatives, our hope for the future is to forge ties between the dots. We believe that literally creating a network by connecting the involved actors with one another, will benefit the education for (ex-)NAMS. In doing so, these actors will have more access to the available but currently insufficiently exploited social capital. We are aware of the fact that the list of proposed networking initiatives in this manuscript is not exhaustive. More (practical) research on building social networks in the context of education for (ex-)NAMS as well as a thorough exploration of today’s stand-alone practices that network actors are setting up on their own initiative are desirable.

Striving for an optimal, ideal network is not realistic nor desirable. A good working network is context-dependent and influenced by micro-meso-and macro-barriers and enablers. In this respect, the take home message of our story is not that THE one-size-fits-all network should be installed in the Flemish education system for NAMS, but that all actors involved should be challenged to reflect on their own role and should be encouraged to enter into dialogue with one another. Only by really connecting the dots, can the available and valuable social capital present be used for the ultimate aim, that is to offer (ex-)NAMS the high-quality education they need.