1. Introduction

Competency-based models of medical education require a programmatic approach to assessment [

1,

2]. Conceptually, a program of assessment has been described as a system made up of interrelated and interdependent elements (i.e., people, decision-making tools and processes, and records of reporting), which continually influence one another to achieve larger, complementary purposes (i.e., promotion of personalized learning, identification of resident readiness for independent practice, and information about program efficacy) [

3,

4]. With programmatic assessment and competency-based medical education (CBME), higher-stakes decisions about resident progress, promotion, or remediation must be defensible and rooted in samples of lower-stakes workplace-based assessment which, when triangulated within workplace-based assessments and across other forms of assessment data (e.g., Objective Structured Clinical Exams, written exams), can demonstrate patterns of performance across contextual variables, such as time, patient/case characteristics, and assessors [

5]. Further elaborating on models of programmatic assessment, it has been proposed that a program of assessment in CBME involves subsystems, including two co-dependent cycles (one of knowledge (assessment data/information) production and one of knowledge use), and that high-stakes decisions (e.g., about progress, promotion, and remediation) are only as trustworthy as the knowledge being produced, documented, and used to inform such decisions [

6].

Translating programmatic assessment theory to practice has remained a challenge for program leaders and faculty responsible for designing, implementing, and sustaining these systems [

7,

8]. Programs are highly sensitive to contextual factors, such as the people and resources available to fuel and sustain the system [

6]. These people often serve in multiple roles/capacities (e.g., a faculty member who also serves on the Competence Committee), thereby adding to the system complexity. Although guidelines to support the operationalization of programmatic assessment are being published [

9], there is still a need for case studies that present implemented models of programmatic assessment in different education contexts to understand and highlight emerging implementation challenges and foster problem-solving across centres.

We have found that most case studies of programmatic assessment take a top-down approach and consider how the design elements of the program of assessment may influence residents’ engagement in learning and performance/achievement [

7,

10,

11,

12]. However, it is conceivable that perceived differences in residents’ engagement and strength of performance may reciprocally influence the functioning of the program of assessment, both holistically and when considering subcomponent parts. From a practical perspective, both of these variables (engagement in assessment processes and performance strength) are observable and are often topics of discussion between residents, academic advisors, and competence committee members [

13]. From a theoretical perspective, engagement in assessment and the ability to demonstrate strong performance are important contributors to resident success within CBME programs [

14]. Thus, the purpose of this research was to take a learner-centred approach to explore how sample resident archetypes (sample profiles along two continua: engagement and performance strength) may influence the workings of programs of assessment across multiple medical specialty training programs and institutions. Specifically, our research questions were as follows: (1) Does our previously developed model of programmatic assessment (PA), which is based on the operationalization of PA within one EM program at Queen’s University [

6], reflect the models being operationalized in other institutions and medical specialties?; (2) Is this model of PA sensitive to differences in resident engagement and strength of performance?; and (3) Does resident engagement and strength of performance influence the perceived functioning of programs of assessment in similar ways, across programs and specialties?

Programmatic Assessment Model

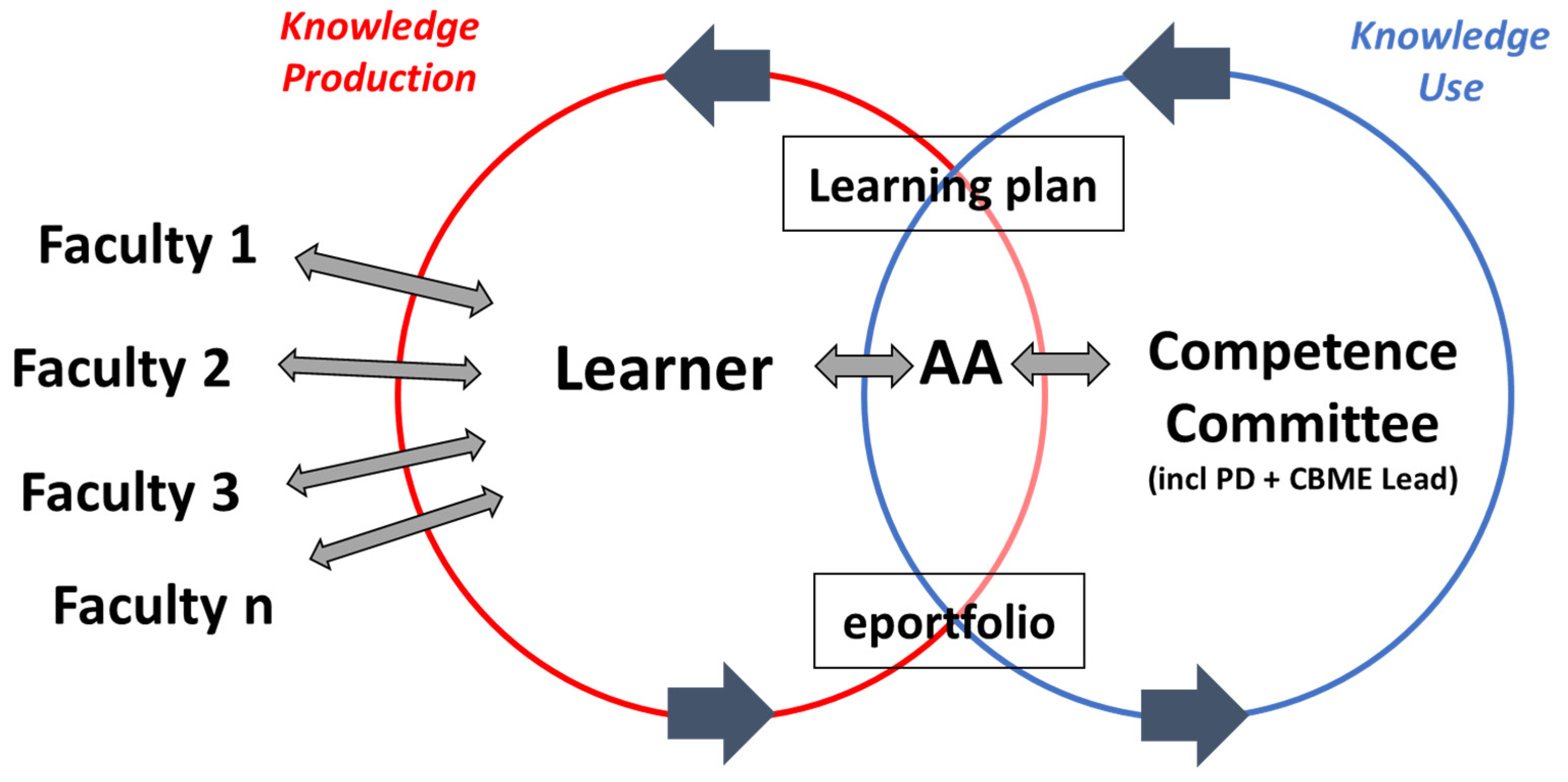

The evidence-based model of programmatic assessment used for this study (

Figure 1) represents a program of assessment as a system with two co-dependent knowledge (information) cycles: one of knowledge production (red) and one of knowledge use (blue). Information is produced when a faculty member, or a more competent other, formatively assesses a resident’s performance and documents key information about the resident’s performance in their ePortfolio, often in the form of an entrustment score with narrative feedback. Residents and their advisors later use these documented assessments to engage in resident assessment when self- and co-regulating the resident’s learning in advance of and during progress meetings. At a later point in time, Competence Committee members use this same information documented within the resident’s ePortfolio to collaboratively interpret patterns of performance and make high-stakes summative/evaluative decisions about the resident’s progress, promotion, or remediation. Academic Advisors may (or may not) take the lead on presenting and discussing a resident’s performance information (evidence) to the Competence Committee to inform their summative decision making (dependent on policy). Formalized evaluative decisions and feedback from the Competence Committee is then documented in the resident’s ePortfolio and used by the resident and their Academic Advisor to inform ongoing workplace-based learning and assessment opportunities. A key to support interpretation of the model and its components is provided in

Figure 1.

This model of programmatic assessment suggests that faculty responsible for conducting low-stakes frontline formative assessments may not know how the same information will be later used to make high-stakes summative/evaluative decisions about residents’ achievement of competence standards. Competence Committee members who use artefacts from workplace-based assessments (e.g., entrustment scores and narrative feedback) may struggle to make high-stakes decisions about resident remediation, progress, or promotion because of incomplete or problematic evidence documented in situ [

15]. Thus, there is thought to be a knowledge (information) gap between ‘two communities’ [

16]: faculty who initially produce and faculty who later use resident performance information. This knowledge gap is thought to exist because of limited opportunities for faculty to interact, communicate, and adequately document critical information about resident performance.

3. Results

Research participants (n = 17) included competence committee members and academic advisors from four different postgraduate specialty programs across Canada.

Table 1 reports the number of participants from each specialty program. Our sample included diversity in medical specialty and program size. We have intentionally omitted the names of the programs’ institutions to protect the confidentiality of the participants.

First, we describe how each program modified the base model to reflect their system of programmatic assessment more accurately. Next, we summarize and discuss how the four specialty programs represent the influence of each resident archetype on the system of programmatic assessment.

3.1. Improvements Made to the ‘Base Model’ of Programmatic Assessment

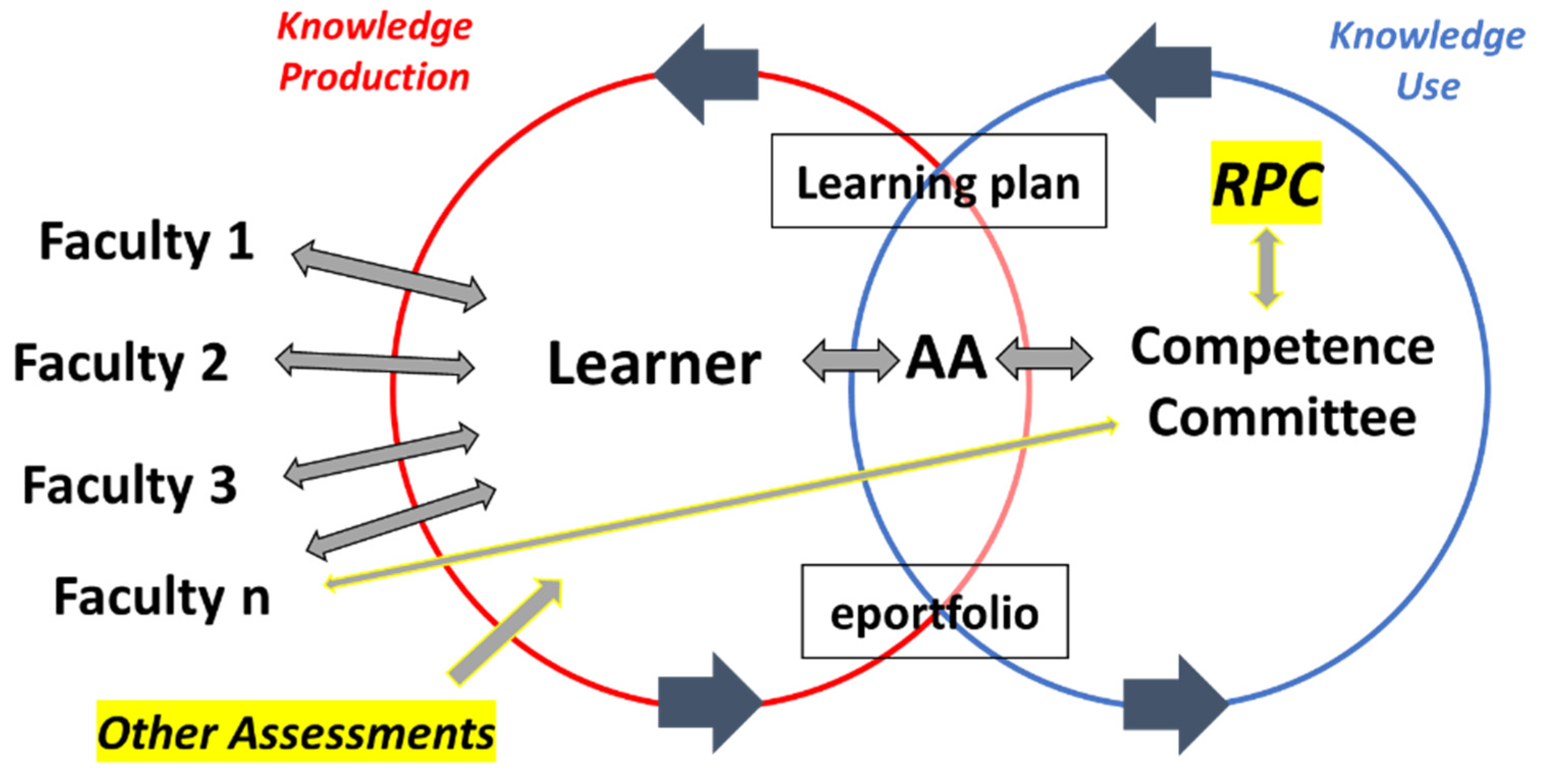

The model of programmatic assessment involving two co-dependent cycles (one of knowledge (assessment data/information) production and one of knowledge use), initially presented as a base/starting model for discussion [

6], resonated with participants from all four programs. Three consistent additions were suggested as improvements to the model, including (1) acknowledgement of additional ‘other assessments’ outside of workplace-based assessments, such as Objective Structured Clinical Exams and written specialty examinations; (2) decision making by the Residency Programs Committee (RPC); and (3) direct communications between faculty and member(s) of the Competence Committee, which circumvent the resident and their e-portfolio (highlighted components within

Figure 2). These findings suggest that this newly revised model has some face validity: on the surface, it appears to accurately model how programmatic assessment works in practice.

3.2. Support for the Four Resident Cases (‘Archetypes’)

The four resident cases presented and discussed as archetypes (sample profiles) resonated with participants across all four specialty programs. Even though engagement and performance strength are two continua, participants mentioned and even agreed upon specific residents (past or current) who ‘came to mind’ as a typical example of a resident who met the description of each of the four cases. These findings would also suggest that the proposed resident cases (‘archetypes’) have some face validity.

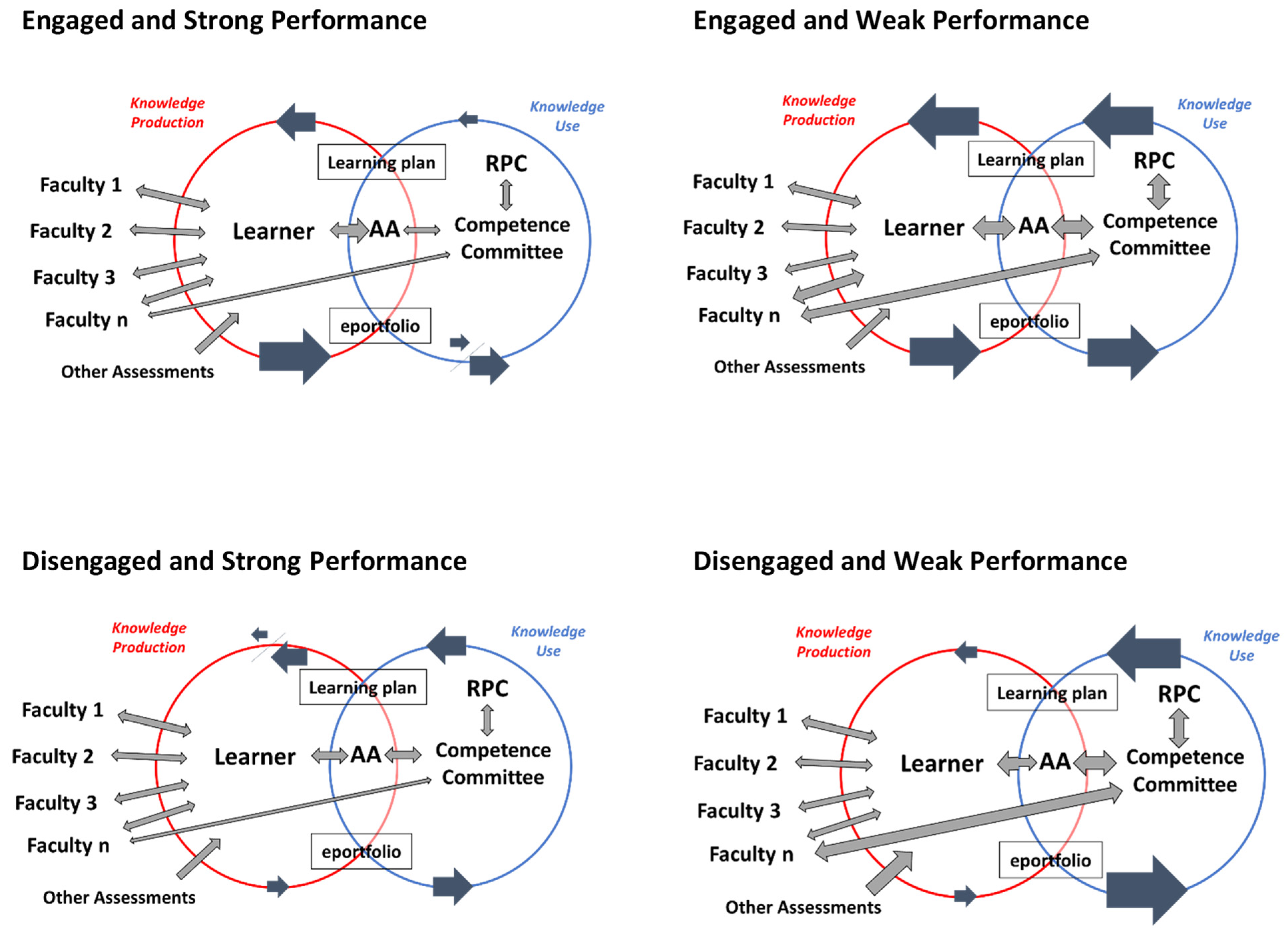

3.3. Do Resident Archetypes Influence the Functioning of Programs of Assessment?

Participants agreed and were able to easily explain how differences in resident engagement and performance influence the co-dependent cycles of knowledge production and use through interactions between program stakeholders and program elements. First, we will independently describe and then model (

Figure 3) the influence of each resident archetype using recurrent ideas and participant quotes from the four programs/focus groups. Next, we will provide a summary comparing and contrasting the influence of each resident archetype on key program elements/relationships (

Table 2). To help readers understand the relationship between the notation used in the models (

Figure 3) and summary (

Table 2), we have described the connections in parentheses for Case 1 (as an example to support interpretation).

3.4. Case (Archetype) 1: Engaged and Strong Performance

Participants agreed that these residents tend to generate ‘lots of assessment data’ through workplace-based assessments with frontline faculty and ‘engage more’—especially with their Academic Advisor (larger arrows, representing more of these interactions and resultant information going into the resident’s ePortfolio). Given the wealth of information documented over time about their performance, review of these residents’ ePortfolios is considered ‘minor’, meaning that not much time is spent interpreting the information to decide their progress unless it is suggested that they be promoted to an ‘accelerated path’ or ‘advanced learning plan’. If this happens, more time is spent discussing and synthesizing evidence to document the expedited learning trajectory and develop the advanced learning plan for approval by the RPC (more or less time is represented as up/down arrows). Otherwise, if these residents are ‘progressing as expected’, very little information is communicated through their Learning Plan (i.e., ‘good job’, ‘keep going’, etc.) (represented as a smaller arrow).

3.5. Case (Archetype) 2: Engaged and Weak Performance

Participants agreed that residents who are engaged but weakly performing also tend to generate ‘lots of assessment data’ and ‘engage more’ with their Academic Advisor. However, much more time is spent by the competence committee generating a reliable and transparent summative decision about their performance. There are thought to be several possible reasons for this, including the large quantity of available workplace-based assessment data, variability in scored performance and feedback across assessments, and vaguely completed assessments (requiring ‘reading between the lines’ [

24]) and/or additional information brought forth to competence committee members through ‘backend hallway conversations’ [

21]. Consequently, participants agreed that they will sometimes need to ‘go back and target faculty to specifically provide context to make sense of the resident’s data’ or ‘get additional information’ to fill in the blanks and make sense of these residents’ performance. Given the ‘close attention’ devoted to reviewing and discussing these residents’ performance, Competence Committees often have ‘lots of formalized feedback’ to share in their learning plans.

3.6. Case (Archetype) 3: Disengaged and Strong Performance

Participants agreed that residents who are disengaged but strongly performing tend to generate ‘less, but more consistent’ workplace-based assessment data. While Academic Advisors may have to rely more on other assessments to inform their summary of these residents’ performance, discussion and summative decision making by the Competence Committee does not take more time. Often, the summative feedback shared with the resident is simply to ‘get more assessments.’ This feedback tends to temporarily motivate these residents to re-engage in workplace-based assessments; however, even though their performance is strong, their motivation tends to drop off again over time, resulting in ongoing issues of limited performance information.

3.7. Case (Archetype) 4: Disengaged and Weak Performance

Participants agreed that residents who are disengaged and weakly performing tend to generate ‘less and more variable’ workplace-based assessment data. Consequently, Academic Advisors and Competence Committee members tend to spend the most time discussing the performance of these ‘few’ residents. More time is spent ‘making sense of what little assessment data is available’. Consequently, more attention is given to results from other assessments, and Competence Committee members are compelled to consult targeted faculty members to provide more anecdotal information about these residents’ performance. Given the amount and gravity of the formalized feedback to be shared with these residents, the Competence Committee engages the Residency Program Committee in a more in-depth discussion to approve escalating their learning plans to ‘modified’ status. However, despite receiving a modified learning plan that includes ‘big recommendations for improvement’, the participants agreed that these residents’ disengagement in workplace assessments tends to persist.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study offer important and novel insights into the modelling and implementation of programmatic assessment across specialist residency training programs, institutions, and resident archetypes (sample profiles across two continua: engagement and performance strength). First, we found evidence to suggest that our previously developed model of programmatic assessment (

Figure 1), which is based on the operationalization of programmatic assessment within one Emergency Medicine program at Queen’s University [

6] is reflective of the models being operationalized within four different postgraduate programs and four separate institutions. Second, small but important improvements have been suggested to refine some of the details of this model (

Figure 2). Together, these findings suggest that this working model has some face validity for programmatic assessment stakeholders. Third, we have found that our working model is sensitive to differences in resident engagement and strength of performance (

Figure 3). Each of the four resident archetypes influenced components of the model in different ways and have yielded some important ‘lessons learned’ for other programs looking to implement, improve upon, or evaluate their program of assessment.

First, we have learned that residents who are engaged in formative assessment and perform strongly likely do not receive as much return on their investment in this model of programmatic assessment as implemented. This finding refutes a key promise of CBME: that all residents, and not just those who are struggling, will benefit from being engaged in a system of PA [

5]. We found evidence to suggest that these ‘high-functioning’ residents are likely being ‘short-changed’ in terms of the formalized summative feedback they receive from their Competence Committees. This finding has also been suggested by the Fédération des médicins résidents du Québec’s (FRMQ) survey of residents and their experiences with CBME in Canada [

25]: that not all residents are seeing an increase in the quality of formalized summative feedback received via individualized learning plans generated by their Competence Committee. This may result in high-functioning residents becoming increasingly sceptical of their time investment in programmatic assessment if they continue to receive low pedagogical return. That said, if CBME programs are being implemented as intended, these residents should be getting more criterion-referenced feedback than they had before on workplace-based assessments [

26]. However, it is still unclear if feedback to residents is actually improving [

27,

28].

Second, we have learned that despite these programs’ designs and developmental intentions for implementation, weaker performing residents may promote a problem identification paradigm [

29], whereby Academic Advisors and Competence Committee members are faced with making sense of ‘problematic evidence’ [

15] and reach outside of the formal system of programmatic assessment in place to solicit additional information from faculty. Consequently, this may result in the acquisition and use of ‘less defensible’ data to inform higher-stakes summative decision-making. In our study, participants explained how ‘other systems get activated’ when a resident is ‘flagged’ or thought to be ‘in trouble’. While some of these sub-systems are positive, such as engagement of the Residency Program Committee, other sub-systems, such as informal hallway conversations, emails to the Program Director or individual members of the Competence Committee, or Academic Advisors and/or Competence Committee members drawing upon their memories of first-hand anecdotal experiences working with the residents in question, could be maladaptive in that they have the potential to magnify possible biases and inequities [

30].

Together, these two lessons learned motivate us to fulfil the potential of PA in CBME by more intentionally and strategically challenging those who are engaged and strongly performing, and by anticipating ways that weakly performing residents may challenge or strain existing programmatic assessment components and processes. While our study sheds some light on the ways that different resident archetypes can potentially influence the functioning of programs of assessment, we must also consider its limitations. Participants represented a sample of Academic Advisors and/or Competence Committee members from four different specialties and institutions, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings. However, our sample does include representation from diverse specialties and program sizes across Canadian provinces. In addition, our semi-structured approach to asking focus group questions, while concurrently adapting the base model of programmatic assessment to reflect participants’ experiences, may have steered participants to share their perceived experiences rather than their actual experiences. Further, the software utilized (Microsoft PowerPoint) limited the graphical representation. We did not observe any Competence committee meetings to confirm or refute their self-reported experiences or approaches. Rather, we relied on group discussion and consensus to ratify changes made to components of the model of programmatic assessment to reflect the influence of each resident archetype (presented in

Figure 3). Finally, we did not focus in detail on the nuances and differences in the nature of the interactions between frontline faculty assessors and different resident archetypes beyond the generation of assessment data. While our findings suggest that engaged and strongly performing residents have a lack of summative returns, it may be that improved frontline interactions (not reflected in this model) such as more moments of formative assessment and/or more targeted assessments and feedback may be returns not captured here.

5. Conclusions

The continued interest and investment in competency-based approaches to medical education challenge us to better understand how we design, implement, and evaluate programs of assessment to meet the needs of residents, educators, program leaders, and patients. Our participants, representing four residency programs of different sizes and medical specialties, suggest how differences in resident engagement and performance strength can influence the functioning of their programs of assessment in some (mal)adaptive ways. For the few residents who are disengaged and weakly performing, significantly more time is thought to be spent by Academic Advisors and Competence Committee members to make sense of problematic evidence, arrive at a decision, and generate recommendations for improvement. In contrast, for the vast majority of residents who are engaged and perform strongly, significantly less time and energy are spent on discussion and formalized recommendations to challenge their ongoing growth and development. While some trade-offs exist in any program with limited resources, it does seem unfair that those residents who are investing more effort receive less return on their investment. Thus, we are challenged as a medical education community to consider ways that we can make programmatic assessment more equitable in terms of the realized benefits for all learners.