Cohort-Based Education and Other Factors Related to Student Peer Relationships: A Mixed Methods Social Network Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Literature on Graduate Student Peer Relationships

1.2.1. Individual Attributes Related to Student Peer Relationships

1.2.2. Cohort-Based Learning and Student Peer Relationships

1.2.3. Social Network Factors Related to Student Peer Relationships

1.3. Gaps in the Knowledge and Current Study

- RQ 1 (Qualitative): After graduation or near the end of their programs, what are MSW students’ perspectives of their peer relationships during the program and the role of cohort-based education on their peer relationships?

- RQ 2 (Qualitative and Quantitative): What individual, institutional (e.g., cohort-based learning), dyadic, and network structural factors are associated with MSW student friendships?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Setting

2.2. Recruitment and Sample

2.3. Qualitative Data Collection

2.4. Qualitative Data Analysis

2.5. Quantitative Data Collection

2.6. Quantitative Measures

Dyadic Variables

2.7. Quantitative Data Analysis

Curved Exponential Family (CEF) Models for Correlates of Friendship Ties

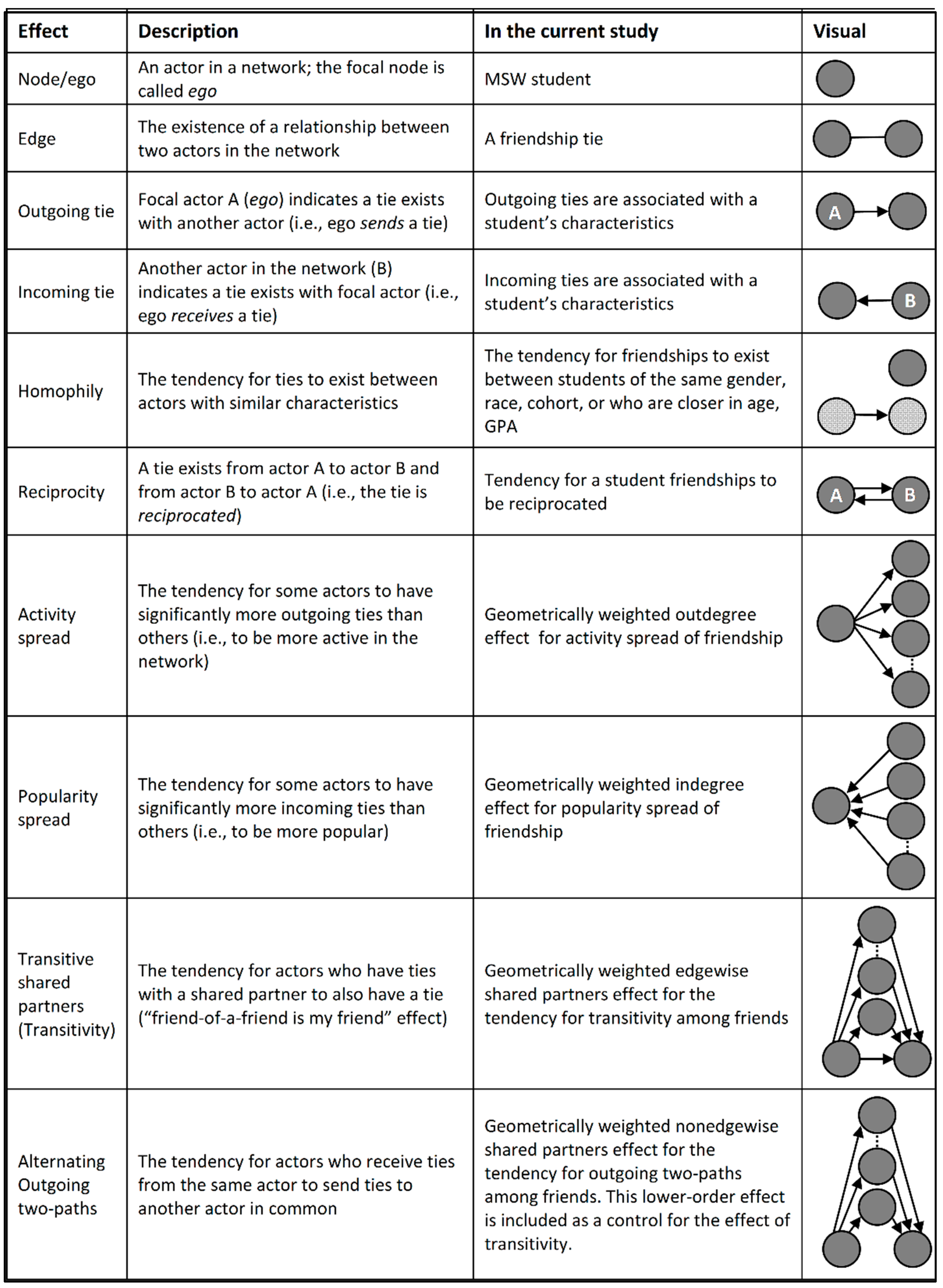

- Network structural effects. Our model included network structural effects of edges (i.e., the propensity for a tie to exist given the rest of the model), reciprocity, transitivity, and the degree effects of popularity spread (i.e., the tendency for a high degree of variation in the popularity of students in the network) and activity spread (i.e., the tendency for a high degree of variation in the number friends reported by students in the network). We also included two-paths, a lower-order structural effect necessary to control for when identifying transitivity effects. If the parameter estimate for two-paths are significant and negative and the parameter estimate for transitivity is significant and positive, then a tendency toward transitivity is detected in the network and is likely not occurring by chance). Figure 1 provides definitions and visual depictions of these network structural effects.

- Individual-Level Attributes. We also included the effects for the following individual-level attributes on the likelihood that students would report having friendships (i.e., outgoing tie) or be named by other students as a friend (i.e., incoming tie): age, gender, race/ethnicity, incoming grade point average. In addition, we included the homophily effects for these individual-level attributes.

- Dyadic and Institutional Factors. We operationalized homophily for the categorical variables of gender, and race/ethnicity as two students having the same value of the variable. For the continuous variables of age and grade point average, homophily was operationalized as the absolute difference between two students’ values of the variable, such that dyads with smaller absolute differences on the variable were more homophilous than those with greater absolute differences. The model also included the effects of students being in the same cohort, having multiplex social relationships at the end of the first semester, taking classes together after the cohort experience ended, and students living in proximity to one another (i.e., within 10 km).

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Findings

- Theme 1: Students valued having interrelated academic, professional, and friendship relationships and credited the cohort system with fostering an environment where these multiplex ties could develop.

Because of the academics that were already learned from each other, it fueled our personal relationship and then vice versa, through our personal relationship we learned about how we work as students and how we could help each other even if we’re not in the same group. (FG3)

I think that personal is always at the heart, always most important because you did need those friends to confide in and rely on when things were tough … I don’t think I would have really survived grad school and been able to cultivate other types of relationship—the professional or the academic—um without having kind of those underlying core personal relationships that were so fundamental to my survival in grad school. (FG1)

There are people that I gravitated towards professionally and there are people that I gravitated towards personally, but the people that I gravitated towards just personally, I’m not as close to. The people that I gravitated to professionally, I still am. But the people that I gravitated to both, I’m the closest to. (FG1)

I totally will because I’ve learned that the people I relied on or trusted throughout the cohort system and then developed a friendship with maybe, or even just, outside the cohort system too I would do this, they’re going to be a resource and a possible ally out in the field where I can use them as a resource or just even a source of knowledge or connections. And, you know, kind of build it from there. (FG3)

- Theme 2: The cohort system helped students develop relationships with and gain appreciation for people who were different in background and perspective.

There are people that I am absolutely sure I would have never followed up with in conversations if I hadn’t seen them multiple times in my classes over and over. Um, just people that aren’t necessarily you know, like me or they have their own clique or whatever. (FG2)

We had lots of group activities within the classroom, within the cohort where we had to split up into different groups than we were normally in and it was forced interaction. But it was really valuable, um, because we would just start to engage and I would learn some things that I don’t think I would have normally. (FG2)

I thought that was really important because I not only made friendships, but I also got to know a lot about other people’s perspectives throughout especially the first semester, building that cohort. Um, and the kind of level of intimacy we got to in the classroom within a class period was unexpected and a lot of times profound. (FG2)

So it did feel like there was just this respect for each other that was built. Throughout the first semester by recognizing, ‘cause you would be so frustrated with someone who was monopolizing or someone who is this and then you hear something that they say and then you’re like, “god, they’re just people who are trying to work through their shit.” ‘Cause we all have our shit and we’re all just trying to get through it. And so you do feel this sense of we may not agree and there are people who are irking my nerves to the highest degree … but today I would call them and ask them for an opinion if I needed it on something that they do because you’re taught over that first semester that we’re all here just trying to make it. So that respect and that trust to a certain extent. (FG1)

- Theme 3: Students gravitated towards others who were similar across different categories within the cohort.

It’s not that I disrespect or don’t respect my entire cohort’s opinions and advice, but because I have these personal relationships that came from the cohort that are much deeper and much more similar, I kind of look to those people a little bit more than I would, um, just any one from the cohort. (FG2)

I think there are a handful of people, mostly from my cohort that I talk to on a regular basis. And I think that, again, just comes from similar beliefs and values and interests outside of school and in social work that just kind of because we have the opportunity in our cohort to explore those kind of things we realized how similar we were in different things and enjoyed spending time together and so that kind of developed into a friendship. (FG2)

I think that kind of coupled with that, the academic, um, what’s the word I’m looking for, just this work ethic, you know, was really important. And so, fortunately, I think that we somehow got all of that, you know. Like we have, we all have this really strong, the 4 of us have a really strong work ethic and we just also happened to have a lot of commonality and enjoy one another. (FG1)

I think it came down to their competency level and it came down to their work ethic. Because if it was someone that I kind of felt like was just getting by, whenever I was putting a lot into this program, I was putting everything I had into it. I just didn’t have the, I didn’t feel like I had the time or patience or desire to engage. (FG1)

You don’t have the time to access those other people, maybe to the degree that you would. You know, so I think there’s maybe a time limitation more than desire for me. It’s like (specific students) lived closer to me. (FG1)

- Theme 4: The cohort system helped create a sense of safety and community that was difficult to give up.

I liked the cohorts. Um, it gave me a sense of belonging. It put me in a smaller group. I’m not very social. You know, I’m not real outgoing so I felt safer in a smaller group of people and getting to know people. (FG3)

At first, when I joined the cohort system I thought it was a little bit limiting because I didn’t get to experience as many individuals … but I will say now finishing up my degree, when I go into those classes that are open to anybody and I see individuals from my cohort, I gravitate to them, I trust them more, I feel like we’ve been through stuff together, so it’s almost a sense of security. (FG3)

I was just kind of reflecting back to even being able to stand up in front of a group and present, I mean I’d been out of school for so many years when I came back to this and um, yeah, I don’t think I would have felt comfortable in any of my second semester classes being in front of new people and being able to do that had I not had this kind of primer in a really safe environment with people I felt comfortable with learning how to do group activities or present in front of people. (FG1)

But I do think there was more of a need for personal, personal safety and security and just being completely scared. I mean, I went home the first day of foundation, the first week of foundation or two weeks and cried and was like, “what am I doing? I can’t be a social worker! What have I done? This isn’t what I am supposed to be doing.” I mean, it is, but… So you need someone who you feel like they get that. (FG1)

So, for the first semester, I think it was great. However, you kind of went into the second semester with the same, um, uneasiness, almost that you might have gone into in the original semester without a cohort system because you got to know those 25 or 30 people really, really well. (FG2).

Participants described that their adjustment to no longer being in the cohort (i.e., being uncohorted) consisted of them, “trying to find that person that you know in all of your courses.” (FG1) Another participant said:

I guess I wasn’t necessarily like upset or trying to get in with the other group, but it wasn’t, uh, there wasn’t the same cohesiveness that we had since we had all been through foundation together. (FG3)

Well, it was a little scary again at first because you were going into classrooms and you didn’t know who you were going to see. And I think that I did gravitate toward people that were in my cohort. It gave me somebody to say hi to and then sit with and then you could meet everyone else. So, again, it was kind of like safety. (FG1)

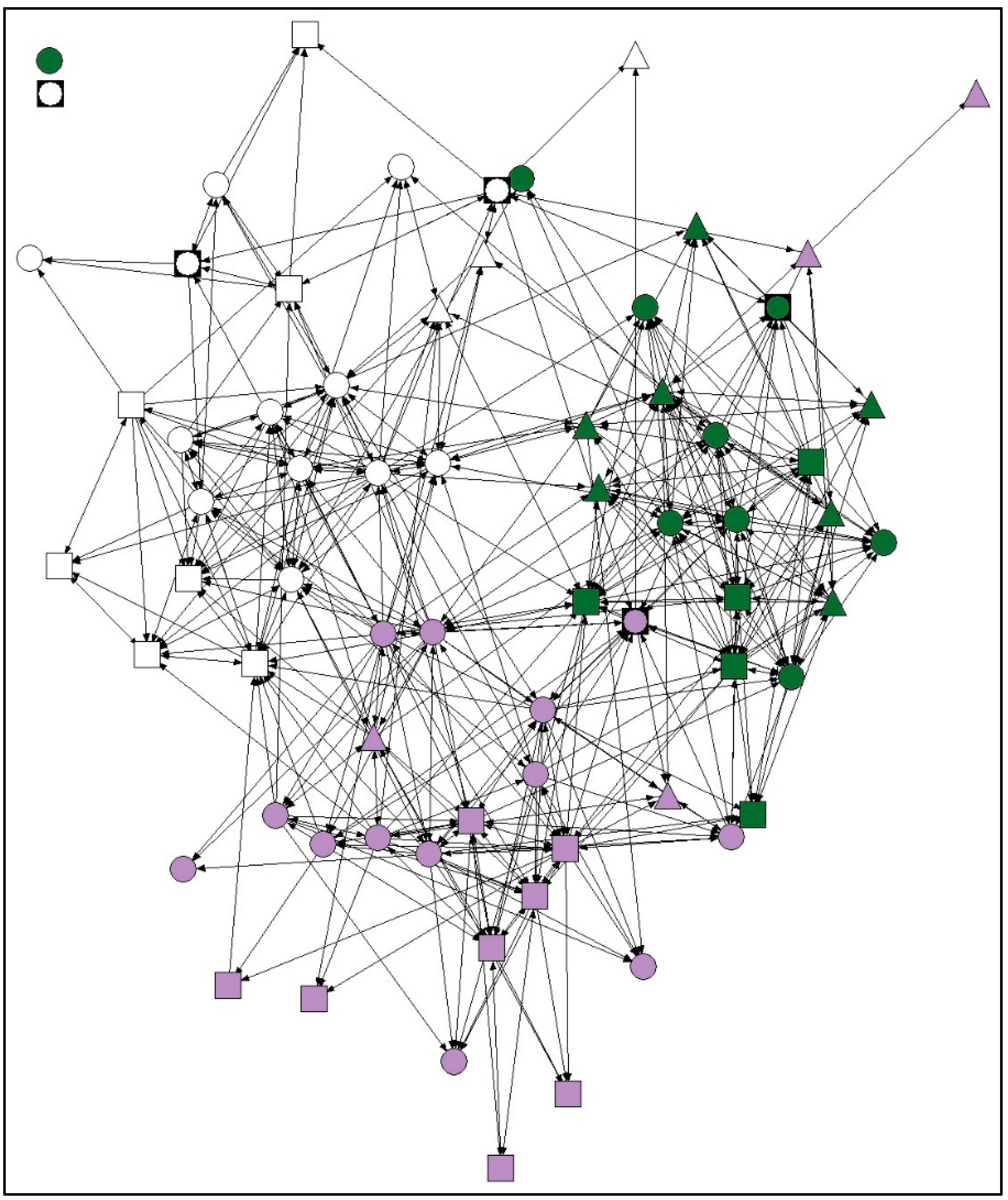

3.2. Quantitative Findings

Curved Exponential Family Model of Friendship Ties Midway through Second Year of Program

4. Discussion

4.1. Individual-Level Factors Associated with MSW Student Friendships

4.2. Homophily

4.3. The Association between Cohort Membership and MSW Student Friendships

4.4. Implications for School Administrators

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bekkouche, N.S.; Schmid, R.F.; Carliner, S. “Simmering Pressure”: How Systemic Stress Impacts Graduate Student Mental Health. Perform. Improv. Q. 2021, 547–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, S.T.; Karnaze, M.M.; Leslie, F.M. Positive factors related to graduate student mental health. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.; Brooks, Z. Graduate Student Mental Health. 2015. Available online: http://nagps.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/NAGPS_Institute_mental_health_survey_report_2015.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Levecque, K.; Anseel, F.; De Beuckelaer, A.; Van der Heyden, J.; Gisle, L. Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kernan, W.; Bogart, J.; Wheat, M.E. Health-related barriers to learning among graduate students. Health Educ. 2011, 111, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, T.; Oswalt, S.B. Comparing Mental Health Issues Among Undergraduate and Graduate Students. Am. J. Health Educ. 2013, 44, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghoroury, N.H.; Galper, D.I.; Sawaqdeh, A.; Bufka, L.F. Stress, coping, and barriers to wellness among psychology graduate students. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2012, 6, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, J.; Baron, R. International postgraduate student transition experiences: The importance of student societies and friends. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2013, 51, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golde, C.M. The Role of the Department and Discipline in Doctoral Student Attrition: Lessons from Four Departments. J. High. Educ. 2005, 76, 669–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, C.; Punch, S.; Graham, E. Transitions from Undergraduate to Taught Postgraduate Study: Emotion, Integration and Belonging. J. Perspect. Appl. Acad. Pract. 2017, 5, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, J.; Manthorpe, J.; Chauhan, B.; Jones, G.; Wenman, H.; Hussein, S. ‘Hanging on a Little Thin Line’: Barriers to Progression and Retention in Social Work Education. Soc. Work Educ. 2009, 28, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, K.A.; Brecht, K.; Tucker, B.; Neander, L.L.; Swift, J.K. Who matters most? The contribution of faculty, student-peers, and outside support in predicting graduate student satisfaction. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2016, 10, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, H.; Ziemer, K.S.; Palma, B.; Hill, C.E. Peer relationships in counseling psychology training. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2014, 27, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, P.; Basilico, M.; Bolotnyy, V. Graduate Student Mental Health: Lessons from American Economics Departments; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://scholar.harvard.edu/sites/scholar.harvard.edu/files/bolotnyy/files/bbb_mentalhealth_paper.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Evans, T.M.; Bira, L.; Gastelum, J.B.; Weiss, L.T.; Vanderford, N.L. Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 282–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinto, V. Dropout from Higher Education: A Theoretical Synthesis of Recent Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 1975, 45, 89–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tinto, V. Universities as Learning Organizations. About Campus. 1997, 1, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysikos, A.; Ahmed, E.; Ward, R. Analysis of Tinto’s student integration theory in first-year undergraduate computing students of a UK higher education institution. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 2017, 19, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, E.T.; Chapman, D.W. A multiinstitutional, path analytic validation of Tinto’s model of college withdrawal. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1983, 20, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudin, B.; Roth, R.; Greenwood, J.; Boudreau, L. Science cohort model: Expanding the pipeline for science majors. J. First-Year Exp. Stud. Transit. 2002, 14, 105–132. [Google Scholar]

- Rüegg, S.T. Comparing Cohort Model and Non-Cohort Model Program Design as a Mechanism for Increasing Retention and Degree Completion. Ph.D. Thesis, Northcentral University, La Jolla, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti, M.d.C. Revisiting the Tinto’s theoretical dropout model. High. Educ. Stud. 2019, 9, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, R. Student dropout in distance education: An application of Tinto’s model. Distance Educ. 1986, 7, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.T.; Soderstrom, S.B.; Uzzi, B. Dynamics of Dyads in Social Networks: Assortative, Relational, and Proximity Mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 36, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McPherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Cook, J.M. Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Klepper, M.; Sleebos, E.; van de Bunt, G.; Agneessens, F. Similarity in friendship networks: Selection or influence? The effect of constraining contexts and non-visible individual attributes. Soc. Netw. 2010, 32, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skvoretz, J.; Agneessens, F. Reciprocity, Multiplexity, and Exchange: Measures. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomi, A.; Snijders, T.A.; Steglich, C.E.; Torló, V.J. Why are some more peer than others? Evidence from a longitudinal study of social networks and individual academic performance. Soc. Sci. Res. 2011, 40, 1506–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tyagi, A.; Gomez-Zara, D.; Contractor, N.S. How do friendship and advice ties emerge? A case study of graduate student social networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM), virtually online, 7–10 December 2020; pp. 578–585. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Hua, Y. The role of shared study space in shaping graduate students’ social networks. J. Facil. Manag. 2021, 19, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degeneffe, C.E.; Grenawalt, T.A.; Kesselmayer, R.F. Relationship Building in Cohort-Based Instruction: Implications for Rehabilitation Counselor Pedagogy and Professional Development. Rehabil. Res. Policy Educ. 2021, 35, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathe, R.S. Using the Cohort Model in Accounting Education. Account. Educ. 2009, 18, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swayze, S.; Jakeman, R.C. Student Perceptions of Communication, Connectedness, and Learning in a Merged Cohort Course. J. Contin. High. Educ. 2014, 62, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtfeld, C.; Vörös, A.; Elmer, T.; Boda, Z.; Raabe, I.J. Integration in emerging social networks explains academic failure and success. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 116, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rubin, M.; Wright, C.L. Time and money explain social class differences in students’ social integration at university. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, J.; Engels, M.C. The role of prosocial attitudes and academic achievement in peer networks in higher education. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, J.; Flache, A.; Jansen, E.; Hofman, A.; Steglich, C. Emergent achievement segregation in freshmen learning community networks. High. Educ. 2017, 76, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noyens, D.; Donche, V.; Coertjens, L.; Van Daal, T.; Van Petegem, P. The directional links between students’ academic motivation and social integration during the first year of higher education. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 34, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Gorelick, D.; Short, K.; Smallwood, L.; Wright-Porter, K. Academic cohorts: Benefits and drawbacks of being a member of a community of learners. Education 2011, 131, 497–504. Available online: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=AONE&u=googlescholar&id=GALE|A253740208&v=2.1&it=r&sid=AONE&asid=63457512 (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- Maher, M.A. What Really Happens in Cohorts. SAGE J. 2004, 9, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczensky, L.; Pink, S. Ethnic segregation of friendship networks in school: Testing a rational-choice argument of differences in ethnic homophily between classroom- and grade-level networks. Soc. Netw. 2015, 42, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.; Trenga, M.E.; Weiner, B. The Cohort Model with Graduate Student Learners: Faculty-Student Perspectives. Adult Learn. 2005, 16, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyola University Maryland School of Education. Available online: https://www.loyola.edu/school-education/academics/cohorts (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- USC Marshall School of Business. Available online: https://www.marshall.usc.edu/programs/mba-programs/online-mba/what-are-benefits-cohort-based-online-mba-program (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- UTA School of Social Work. Available online: https://www.uta.edu/academics/schools-colleges/social-work/programs/msw/cohort (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Maher, M.A. The Evolving Meaning and Influence of Cohort Membership. Innov. High. Educ. 2005, 30, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godley, J. Preference or propinquity? The relative contribution of selection and opportunity to friendship homophily in college. Connections 2008, 1, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Apugo, D.L. “We All We Got”: Considering Peer Relationships as Multi-Purpose Sustainability Outlets Among Millennial Black Women Graduate Students Attending Majority White Urban Universities. Urban Rev. 2017, 49, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y. International graduate students’ difficulties: Graduate classes as a community of practices. Teach. High. Educ. 2011, 16, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauldin, R.L.; Narendorf, S.C.; Mollhagen, A. Relationships among Diverse Students in a Cohort-Based MSW Program: A Social Network Analysis. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2017, 53, 684–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossinets, G.; Watts, D.J. Empirical Analysis of an Evolving Social Network. Science 2006, 311, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robins, G.; Pattison, P.; Kalish, Y.; Lusher, D. An introduction to exponential random graph (p*) models for social networks. Soc. Netw. 2007, 29, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSWE Commission on Accreditation. EPAS Handbook. 2005. Available online: https://www.cswe.org/accreditation/accreditation-process/2015-epas/S (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Froehlich, D.; Rehm, M.; Rienties, B. Reviewing Mixed Methods Approaches Using Social Network Analysis for Learning and Education. In Educational Networking; Pena-Ayala, A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 43–75. [Google Scholar]

- Colby, I.C. Rethinking the MSW Curriculum. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2013, 49, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G.; Freeman, L.C. Ucinet 6 for Windows: Software for Social Network Analysis; Analytic Technologies: Lexington, KY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- OpenStreetMap Contributors. Planet Dump [Data File from “planet-200921.osm.pbf”]. 2020. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS (Version 3.16). Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. 2020. Available online: https://qgis.org/en/site/ (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Raffler, C. QNEAT3 (Version 3). 2018. Available online: https://root676.github.io/ (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Borgatti, S.P. NetDraw Software for Network Visualization; Analytic Technologies: Lexington, KY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, D.R. Curved exponential family models for social networks. Soc. Netw. 2007, 29, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kossinets, G. Effects of missing data in social networks. Soc. Netw. 2006, 28, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Handcock, M.S.; Hunter, D.R.; Butts, C.T.; Goodreau, S.M.; Krivitsky, P.N.; Morris, M. ergm: Fit, Simulate and Diagnose Exponential-Family Models for Networks. The Statnet Project (http://www.statnet.org), 2018. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ergm (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- Valente, T.W.; Fujimoto, K.; Unger, J.B.; Soto, D.W.; Meeker, D. Variations in network boundary and type: A study of adolescent peer influences. Soc. Networks 2013, 35, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windzio, M.; Bicer, E. Are we just friends? Immigrant integration into high- and low-cost social networks. Ration. Soc. 2013, 25, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistic | Definition | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Density | Density is a measure of a network’s cohesion and is calculated by dividing the total number of ties that exist in a network by the number of possible ties. | Density can range from 0 to 1 with smaller values reflecting sparser networks and larger values reflecting denser networks. |

| Centralization | Centralization measures the extent to which the ties in the network are organized around particular actors in the network. | Centralization can range from 0 to 1 with values of 0 indicating an equal distribution of ties in the network and 1 indicating all ties are centered on one actor. |

| Average distance | Another measure of cohesion that suggests the compactness of the network. Average distance is the mean of the shortest path (i.e., geodesic) between each pair of actors in the network. | |

| Reciprocity (Arc reciprocity) | The percentage of ties in the network that are reciprocated. | Reciprocity values can range from 0 to 1 with greater values indicating greater levels of reciprocity in the network. |

| Transitivity | Transitivity indicates the extent of clustering in a network. It occurs in networks when two people who share a common network partner are also connected to each other (i.e., a “friend-of-a-friend is my friend” effect). Specifically, for a group of three actors a, b, and c, where a has a tie to b and b has a tie to c (i.e., a two-path from a to c), transitivity occurs when a also has a tie to c. The value of transitivity in a network is calculated by dividing the number of transitive triads in a network by the number of two-paths. | Transitivity values can range from 0 to 1 with greater values indicating greater levels of transitivity (or clustering) in the network. |

| Variable | n | % | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 7 | 10.0 | ||

| Female | 63 | 90.0 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Black/African American | 20 | 28.6 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 14 | 20.0 | ||

| White | 31 | 44.3 | ||

| Other | 5 | 7.1 | ||

| Age (20–57) | 28.5 | 9.0 | ||

| Incoming GPA (2.78–4.0) | 3.74 | 0.27 |

| Effect | ϴ | S.E. | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network structural effects | ||||

| Edges | −5.36 | 1.64 | 0.001 | ** |

| Reciprocity | 2.36 | 0.20 | <0.001 | *** |

| Popularity spread (gwidegree) | −0.90 | 0.98 | 0.359 | |

| (decay parameter) | 0.15 | 0.97 | 0.876 | |

| Activity spread (gwodegree) | −1.86 | 0.23 | <0.001 | *** |

| (decay parameter) | 2.21 | 0.19 | <0.001 | *** |

| Transitive shared partners (gwesp) | 0.43 | 0.11 | <0.001 | *** |

| (decay parameter) | 0.53 | 0.21 | 0.011 | * |

| Two-paths (gwnsp) | −0.13 | 0.01 | <0.001 | *** |

| (decay parameter) | 1.61 | 0.52 | 0.002 | ** |

| Individual-level factors | ||||

| Age | ||||

| outgoing ties | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.005 | ** |

| incoming ties | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.060 | |

| homophily a | −0.03 | 0.01 | <0.001 | *** |

| Gender (ref = male) | ||||

| female—outgoing ties | −0.42 | 0.18 | 0.017 | * |

| female—incoming ties | −0.83 | 0.22 | <0.001 | *** |

| homophily b | 0.89 | 0.18 | <0.001 | *** |

| Race/ethnicity (ref = White) | ||||

| Black/African American—outgoing ties | −0.21 | 0.11 | 0.056 | |

| Black/African American—incoming ties | 0.46 | 0.14 | 0.002 | ** |

| Hispanic/Latino(a)—outgoing ties | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.044 | * |

| Hispanic/Latino(a)—incoming ties | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.298 | |

| Other—outgoing ties | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.489 | |

| Other—incoming ties | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.269 | |

| race/ethnicity homophily b | 0.39 | 0.09 | <0.001 | *** |

| Grade point average (GPA) | ||||

| outgoing ties | 0.37 | 0.26 | 0.143 | |

| incoming ties | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.417 | |

| homophily a | −0.36 | 0.31 | 0.251 | |

| Dyadic and institutional factors | ||||

| Same cohort in first semester | −0.21 | 0.16 | 0.192 | |

| Shared classes after first semester (0–11) | 0.80 | 0.14 | <0.001 | *** |

| Proximity of home address proximity (within 10 km) | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.525 | |

| Multiplexity, types of ties at end of 1st semester (0–2) | 1.35 | 0.16 | <0.001 | *** |

| AIC | 1907 | |||

| BIC | 2098 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mauldin, R.L.; Barros-Lane, L.; Tarbet, Z.; Fujimoto, K.; Narendorf, S.C. Cohort-Based Education and Other Factors Related to Student Peer Relationships: A Mixed Methods Social Network Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030205

Mauldin RL, Barros-Lane L, Tarbet Z, Fujimoto K, Narendorf SC. Cohort-Based Education and Other Factors Related to Student Peer Relationships: A Mixed Methods Social Network Analysis. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(3):205. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030205

Chicago/Turabian StyleMauldin, Rebecca L., Liza Barros-Lane, Zachary Tarbet, Kayo Fujimoto, and Sarah C. Narendorf. 2022. "Cohort-Based Education and Other Factors Related to Student Peer Relationships: A Mixed Methods Social Network Analysis" Education Sciences 12, no. 3: 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030205

APA StyleMauldin, R. L., Barros-Lane, L., Tarbet, Z., Fujimoto, K., & Narendorf, S. C. (2022). Cohort-Based Education and Other Factors Related to Student Peer Relationships: A Mixed Methods Social Network Analysis. Education Sciences, 12(3), 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030205