Abstract

The aim of this article is to provide a systematic review of the transversal competencies for employability in university graduates from an employer’s perspective, with consideration to the importance of the topic in the cross-national context. The PRISMA statement was used to guide the methodology and the reporting for the systematic review. The data collection produced 52 articles from the Scopus and Web of Science (JCR only) databases in the ten years between 2008 and 2018. The analysis focused on the characteristics of the employers and organizations, the methods and the instruments for evaluating transversal competencies, and the most highly valued competencies, both internationally and by continent. One of the main contributions is the creation of a classification that is made up of 41 transversal competencies that are grouped into five dimensions. The results show that employers attributed more importance to the competencies in the dimensions of Job-related basic (JRB) skills, Socio-relational (SR) skills, and Self-management (SM) skills. We conclude that Higher education institutions need to incorporate “pedagogies for employability”, which will strengthen the link between the academic setting and the socio-occupational reality and will ensure that graduates make a suitable transition to the world of work.

1. Introduction

In the modern labour market, the strategies of employers for finding new workers are a complex subject. Evidence of that includes the fact that it is still unclear what variables affect graduate employability, which increases the uncertainty about the demands of the labour market and the pressure on HEIs to promote training strategies that help students to become “more employable” [1,2,3].

Particularly in our knowledge economy, employers place great importance on graduates’ transversal competencies—which are also known as “soft skills”—because of the notable benefits for the business performance, the effectiveness in diverse teams, and the drive to innovation [4,5]. There is no doubt that, in the 21st century labour market, “who you are” is as important as “what you know” [6].

Because of that, soft skills are one of the main topics in educational policy at the international level [3], which has led to an increase in the number of publications in multidisciplinary journals on the topic. However, this interest has not been accompanied by consensus in the scientific literature about the identification, definition, or classification of the transversal competencies that graduates need in order to be more employable.

In this context, this paper explores the transversal competencies that employers value most in university graduates, at the international level, through a systematic review. To that end, we established four research questions.

First, we clarify the characteristics of the employers and organizations that employ university graduates. More specifically, we examine the sociodemographic variables of the employers—such as gender, qualifications, and experience—and we also look at their positions within the businesses, the professional sector, the ownership, and the size of the organizations. Secondly, we analyse the methods that were used in the studies reviewed by examining the techniques and instruments that were used, and the classification of the most common competencies. Thirdly, we create a classification scheme for transversal competencies on the basis of the most recent findings in the scientific literature and the results of the systematic review. Lastly, we identify which soft skills the employers in the reviewed studies prioritize when employing university graduates. This analysis is performed on two levels: globally and by continent.

The paper is structured as follows: The following section discusses what the contemporary world of work is like for university graduates, what transversal competencies are indicated by the specialized literature as the enhancers of employability, and which methods are most commonly used to analyse this question in the international research. Section 3 describes the methodology that was used for the systematic review, and Section 4 presents the results in terms of each research objective. Section 5 presents a discussion of the results, in which they are compared to the most recent findings in the literature. The final section presents some concluding remarks.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Employability of Higher Education Graduates in the Contemporary World of Work

Graduate employability has become a hot topic for Higher education institutions (HEIs), and there are two main reasons why it has become so important. Firstly, in today’s complex world, the social mission of HEIs must be aimed at constructing innovative higher education that is able to reduce social inequality and enhance student leadership through education in competencies for dealing with the challenges of the 21st century and Industry 4.0 [7,8]. In this regard, we should not forget that, in addition to integrated, pedagogical, humanistic education [9], HEIs are responsible for preparing their students to effectively enter the labour market [10,11]. Secondly, based on that mission, there is a need to adapt study plans to “pedagogies for employability” [12,13], which contributes to training future employees that are highly skilled and employable in a labour market that is in constant flux [1,2,7,8,10,11,13,14,15,16].

Within this framework, HEIs operate within an uncertain scope of action that needs integrative perspectives on employability. One definition that includes its different dimensions was proposed by Clarke [17], who understands graduate employability as a construct that comprises, “human capital, social capital, and individual behaviours and attributes that underpin an individual’s perceived employability, in a labour market context, and that, in combination, influence employment outcomes” [17] (p. 1931).

Beyond a view of employability that is restricted merely to access to the labour market, the approach that guides the present study focuses on the importance of people’s capacities to be able to contribute to the different contexts in which they act over the course of their lives, which includes social and civic engagement, and economic and social interactions through their work and careers [7,18].

In this regard, universities have a fundamental role in the awareness and development of competencies, as that allows young graduates to be proactive in adapting to work and to the personal and social circumstances that this entails [2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18]. Competence-based curricula in HEIs help graduates to identify professional opportunities, to optimize personal resources to find or secure the work that they want, and to act in various situations where a common goal is sought [1,3,7,8,16,17,18,19,20,21].

Nonetheless, it is worth remembering that the current instability in the job market significantly changes the opportunities for the professional development of graduates. Nowadays, securing a job means understanding the transition to work as a complex process in which, in addition to personal variables (educational attainment, technical and general skills, professional qualifications, etc.), there are a series of external factors, which include the macroeconomic conditions of the market, employment policies, and the beliefs and expectations of the employers [1,7,15,18,22].

Today, changes in the economic structure are visible in aspects such as: the fall in the number of jobs in the manufacturing sector, and the increase in the number of jobs in the service sector; the demand for a workforce that is highly qualified (with higher education) and skilled (in terms of competencies); the increase in the mechanization and automation of work in pursuit of digitization; occupational guidance towards a position of employability security, which requires workers to adapt to unstable and changeable job markets; and the polarization of the job market, which leads to notable differences in pay between professions that require high levels of qualifications and others [7,23,24,25].

In addition, and although the options for working in so-called “high-skill” occupations have increased, there has been little or no growth in well-paid jobs since the year 2000, with even slower growth since the “Great Recession”, which began in 2008 [26]. In consequence, there has been a rise of precarious work, which increases the insecurity in the job market [1,27,28].

In this context, there needs to be a proper understanding of the concept of “employability”. Its definition addresses a person’s self-awareness of the competencies for moving in social and occupational environments that are ever more unstable and turbulent and, therefore, there is a particular link to adaptability and resilience [1,7,15,18,21]. The graduates’ abilities to be aware of and respond to unpredictable environments leads to approaches such as “protean career orientation” [29] and “boundaryless careers” [30], which emphasize an individual’s capacity to adapt and manage changes in the face of the dynamic modern-day job market [1,19].

2.2. Graduate Hiring Patterns: The Role of Transversal Competencies for Employability

In the hiring process, graduates’ lack of professional experience, together with the skill mismatch between their education and the training needed for the job, mean that many highly qualified young people experience long periods of unemployment, find low-paying jobs, or face working with uncertain long-term prospects [28,31,32,33]. Added to that, there are other factors, such as the growing number of workers with higher qualifications and the risk of automation, which underscore the need for people to have high-level competencies that allow them to grow within a company as organizations innovate and increase their productivity [3,9,13,15,26,28,34,35].

Hence, for employers, “being capable” (trained and skilled) and “being someone” (with broad social networks and links) are inherent to the job, and are, therefore, fundamental to graduate employability [28,36,37]. It is for precisely this reason that, in recent years, the discourse in HEIs has focused on the proposal of actions to improve the competencies and personal capital of graduates [6], which increases their ability to “be employable” and to move self-sufficiently through their professional careers [1,3,7,13,17,18,37].

In this way, competencies are defined as valuable goals that are based on the combination and mastery of new knowledge, styles of practice, and attitudes or values that are desirable and formative [38], which makes up a fundamental part of the professional and educational profiles of university graduates. Mertens [39] calls them “competencies for employability”, and understands them to be those competencies that are needed in order to choose a job, to stay in a job, or to find a new job. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that the debate about competencies, which are understood as the development of skills and abilities, is occurring at a time when the study of development economics means a particular focus on the concept of “capacities” [40,41].

The importance of competencies for employability lies within an approach to human capital where education and training are the most important investments [42,43]. They provide a set of marketable skills that increase business productivity, as well as lead to higher salaries and better positions in the job market [3,31,42]. Therefore, if individuals—and their families—invest time and money on improving their educational qualifications and training, they will increase their human capital and, therefore, improve their employability [21].

Similarly, in the context of the demand for highly qualified subjects with broad mastery of competencies, the theories of signalling or filtering [44,45] have been posed as alternatives in explaining hiring processes. These theories are based on the premise that any hiring decision is made under conditions of uncertainty, and that it represents an “investment decision” for employers. Because a person’s competencies cannot be directly observed, those responsible for hiring have to base their evaluation of candidates on the “signals” they provide. According to Forrier and Sels [46], those signals are the individual characteristics or specific activities that the candidate offers that provide the employer with the relevant information about specific capabilities. These include the professional background (curriculum vitae), the academic background (educational qualifications and participation in continued training), and the biographical characteristics (age, sex, family situation). These signals provide the employer with an idea of the individual’s fit and readiness for the job, which may increase the chances of them being hired [6].

However, the literature has already shown that hiring theories need a broader perspective [2], particularly because the hiring decisions of employers are made within a system of beliefs and cognitive patterns [22], and under the institutional or cultural determinants of the organization [47]. In fact, these theories may provide better explanations for the under-representation or discrimination against certain groups in certain industries or sectors because of gender or ethnicity, among other reasons [48].

According to these theories, in the uncertainty of the modern labour market, transversal competencies are especially important, as they are a key element in determining the opportunities that graduates may have to live and work productively and meaningfully throughout their lives [7,18]. Although soft skills have been an important topic in the scientific literature since the middle of the 20th century [42]—which has directly affected the educational offerings of HEIs—recent studies have reported broad and persistent increases in skill requirements since the “Great Recession”. This suggests that the demand for competencies is here to stay, and that many more candidates will need high levels of qualifications in order to compete in the 21st-century job market [5,35].

With that in mind, it could be argued that transversal competencies are becoming more and more important, as they can show employers the graduates’ skills and personality traits, as well as their fit to a position. Much has been written about what differentiates transversal competencies from other types of competencies. Whereas “hard skills” refer to technical and academic knowledge and the abilities needed to perform a certain job [4], “soft skills” cover all of the generic or transversal competencies that reinforce an individual’s employability in a dynamic, fluid, and uncertain market [5]. They can be defined as a “dynamic combination of cognitive and meta-cognitive skills, interpersonal, intellectual and practical skills” that “help people to adapt and behave positively so that they can deal effectively with the challenges of their professional and everyday life” [49] (p. 67).

Empirical evidence indicates that soft skills—or “transversal competencies”—are the most widely demanded by employers because they allow people to improve their individual performances in various tasks while, at the same time, promoting personal development and interaction with others. They are, in short, about knowing how to deal with new situations, being creative, working in groups, demonstrating critical thinking, being sociable, accepting responsibility, and demonstrating leadership [5,9,15,34,35,50]. Considering how important transversal competencies are as an element of human capital and, therefore, as a key dimension of graduate employability [18,39], we may refer to them as “transversal competencies for employability”.

It is worth recalling that the current job market is characterized by team-based and service-oriented roles, which need more social skills than technical abilities [5,15,35]. Therefore, we are now facing a paradigm shift in hiring processes, which have gone from focusing on the mere evaluation of qualifications and technical skills that are related to a position, to a more thorough assessment of each person’s capabilities [36].

Internationally, there have been numerous initiatives aimed at analysing these competencies within the framework of higher education. In Europe, the Tuning, REFLEX and CHEERS projects [51,52,53,54] attempted to establish a predetermined list of transversal competencies to evaluate graduate employability. Various classifications have also been created in response to the attempts of researchers and politicians to define a consensus list of the relevant competencies, such as SCANS in the United States [55], and the USEM model in the United Kingdom [56]. To date, there is no explicit international agreement about the most important transversal competencies for graduate employability, which has increased the uncertainty surrounding the topic [3].

2.3. Evaluation of Transversal Competencies for Graduate Employability: The State of the Question

In the study of graduate employability, the scientific literature has paid significant attention to the influence of factors such as qualifications, social capital, and institutional reputation [37]. Nonetheless, in recent years, there has been notable emphasis by agencies, businesses, and institutions on the evaluation of soft skills, which promote the employability of university graduates [3,5,14,35].

From the perspective of human capital, these evaluations demonstrate the need to analyse competencies that, as transversal overall occupations, are fundamental from the point of view of multidirectional career paths, in which graduates need to know how to intelligently manage their professional trajectories [30]. In turn, that would allow them to avoid the mismatch between study plans in HEIs and the demands of the job market [31,32].

While there have been notable efforts to determine which transversal competencies improve graduate employability, the literature still indicates various challenges. On the one hand, there are few systematic reviews that focus on transversal competencies in different parts of the world [3]. In most cases, the studies of employers have been very specific (dealing with particular knowledge areas, occupations, or geographic regions) and have used very small samples because of the difficulty of achieving large samples of employers [57]. One example is the systematic review by Osmani et al. [58], which looked at two specific sectors in the United Kingdom.

There are also systematic reviews that have incorporated the perspectives of students and employers [14,59]. These studies may have notable biases, as there are clear differences between the perspectives of the two groups about which competencies they feel to be more important for employability [4,50]. Studies have also been published that include grey literature, such as proceedings or publications in specific journals, which reduces the quality and realism of the results somewhat [34]. Similarly, research on this topic should consider the findings from the analysis of online recruitment posts, which, in our eminently digital reality, contain useful descriptors for the evaluation of the hiring requirements, such as information about the job, the required competencies, and the required professional experience, among other things [60].

On the other hand, one of the main problems of the studies that evaluate transversal competencies is the lack of a consensus classification that would allow for a comparison of the occupational requirements at the national level. As was noted previously, in the international context, there are studies with very different labels for competencies, and with long lists or very short lists [3,14,16]. In addition, studies have used very different methods. Some have evaluated competencies through indirect methods, such as the employers’ perceptions or satisfaction with the graduates’ skills, which clearly means that there is subjectivity in the evaluation. In contrast, others have used direct methods, which focus on directly asking the employers about their requirements, or on examining job adverts, which allows for a less subjective analysis [3].

2.4. Study Aim

It is clear that the hiring processes of businesses are affected by many factors that determine how graduates enter and stay in the world of work. This systematic review aims to analyse which university graduates’ transversal competencies or soft skills are most highly valued by employers at the international level. It aims to contribute to the scientific literature by analysing: the characteristics of employers who hire university graduates; the methods that are used to analyse transversal competencies; the identification, definition, and classification of those competencies; and the selection of the most important (Top 10 transversal competencies) for companies in today’s job market. The following research questions (RQs) were formulated:

- RQ1.

- What are the characteristics of the employers and organizations who hire university graduates in the reviewed papers?

- RQ2.

- What research instruments, techniques, and validated classifications do the studies use to assess transversal competencies?

- RQ3.

- What are the most commonly reported transversal competencies in the included papers?

- RQ4.

- What transversal competencies do graduate employers value the most in the international context, according to the reviewed studies?

3. Method

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) [61] was used to guide the methodology and the reporting of this systematic review. The PRISMA is a collection of evidence-based items that helps to ensure the quality of the review process and contributes to replicability. Using this protocol, we describe the criteria for the selection of the articles, the search strategy, and the processes for the extraction and analysis of the data.

3.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

The search was conducted between January and August 2021 using the Web of Science (only Journal Citation Report [JCR] papers) and the Scopus databases, as they have the greatest impact in the international scientific arena. The search was restricted to articles that were published in English or Spanish between 2008 and 2018. This time period was chosen because of the global economic decline that began in 2008. This recession raised unemployment rates in various parts of the world, which led to strict requirements in the “soft skills”. The data collection was conducted by three of the researchers separately (J.G.-A., A.V.-R., and A.Q.-C.).

In order to gather the greatest number of eligible studies, we used a variety of search and Boolean terms. More specifically, we used the equation: (skill* OR competenc*) AND (graduat* OR undergraduat* OR higher education OR universit* OR college* OR degree*) AND (job* OR employ* OR work* OR occupation*) OR (enterprise* OR compan* OR industr* OR business OR firm*). The criteria were that the search terms were included in the study titles, abstracts, or keywords.

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

The articles to be included in the systematic review were selected according to the following criteria:

- Publication type: Papers in journals that were indexed in Web of Science (JCR) and SCOPUS.

- Time frame: Studies published between 2008 and 2018.

- Population: Articles whose participants were graduate employers. Studies that did not include university graduate skill assessments were excluded.

- Context: Papers that included private or public organizations from different professional sectors in the international labour market.

- Types of outcome measures: Studies that provided evidence on the assessment of the “soft skills” that employers valued the most, as well as on the analysis of the competency requirements in the hiring processes for university graduates. The review only included studies that assessed competencies by using Likert-type scales, or that analysed the skill requirements through job advertisements.

- Study type: Articles that assessed the transversal competencies in the different professional sectors with quantitative techniques and research instruments. For mixed studies, only the results that were obtained from using Likert-type scales or other quantitative instruments were used. Previous systematic reviews or theoretical articles were not included.

3.3. Data Collection Process and Quality Assessment

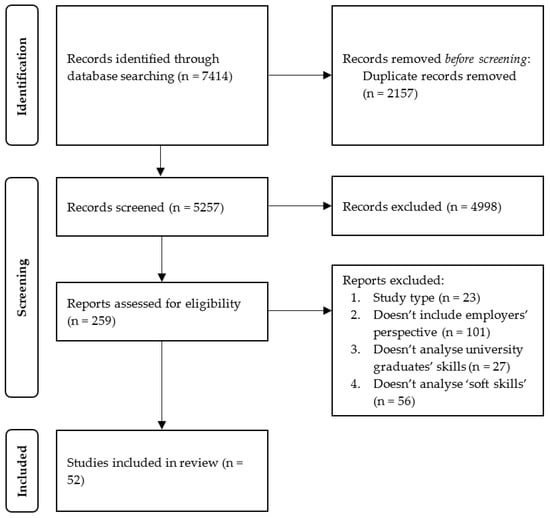

The review process had five phases. In the first phase, we identified 7417 abstracts, which included duplicates. Of those, 3995 were taken from the Scopus database, and 3419 were taken from the Web of Science (JCR). A total of 2157 duplicates were removed, which left 5257 articles.

In the second phase, we reviewed the titles and abstracts, which led to the removal of 4998 articles because they did not fit with the study objective. That left 259 articles to evaluate for eligibility.

In the third phase, the four authors (J.G.-A., A.V.-R., A.Q.-C., and D.P.C.) of this article evaluated the contents of the studies and excluded those that did not match the study questions that had been formulated. Discrepancies were resolved via the authors reaching agreement. To avoid possible bias in the evaluation, the reviewers used “The BIAS FREE Framework” [62]. Following this revision, 207 articles were removed, which resulted in 52 articles being selected. Figure 1 presents a flow diagram of the review process using the PRISMA model [61].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the reviewing process according to PRISMA. Adapted from Page et al. [61].

In the fourth phase, the information in the reviewed articles was coded by using SPSS software (version 27.0). This covered variables such as the year of publication, the geographical origin, the sample characteristics, the methodology/instrument, the types of outcome measures, the professional sector/economic activity, the nature of the organization, and the importance that employers placed on the transversal competencies that were assessed. Table A1 (Appendix A) lists the articles that were included in the systematic review (n = 52), which were used to determine the results. The articles were organized via a paper ID number.

Finally, in the fifth phase, a classification was established for the analysis of the most highly valued transversal competencies in the studies. This began from the classification proposed by Wagenaar [54] for organizing the different competencies. This classification was an update of the classification that was established by the Tuning Project [52], which is one of the most important in Europe. The objective of this project was to establish a common international framework of competencies on the basis of the different knowledge areas in higher education by differentiating the soft skills into three categories [52,54]: instrumental competencies (cognitive, methodological, technological, and linguistic skills); interpersonal competencies (skills in social interaction and cooperation); and systemic competencies (presuming prior acquisition of the previous competencies, skills which involve the combination of understanding, sensitivity, and knowledge).

Wagenaar [54] revised that initial classification by modifying and adding some new transversal competencies, such as the ability to show an awareness of equal opportunities and gender issues, the ability to act with social responsibility and civic awareness, the commitment to the conservation of the environment, and the commitment to health, well-being, and safety.

The starting point for the classification scheme in the present study was to use the labels for each competency in Wagenaar’s [54] list, while also recording the nomenclatures that were used in the reviewed studies. Given the huge diversity, some competencies had to be recoded in order to include those that were not covered by the starting classification. Following that, each competency was re-labelled on the basis of the term that was most often mentioned (see Table A2 (Appendix B)). This phase resulted in a classification that consistently brought together the diversity of the competencies that were found in the reviewed studies.

Once the classification scheme was created, the next step was the analysis of the transversal competencies that were most highly valued for university graduate employability by exploring the importance, both globally and by continent. The criteria for determining which competencies were most highly valued was to select those in the Top 10 positions in the classifications of the studies. In papers with fewer than 10 items, the competencies in the upper half of the list were selected. This method was chosen because of the variety of the classifications and the research instruments that were used in the reviewed studies.

3.4. Description of the Studies Included in the Review

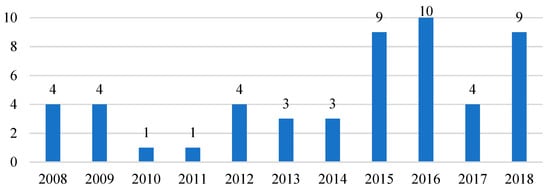

As Figure 2 shows, the year with the most studies was 2016. The results show an increase in the numbers of articles between 2015 and 2018.

Figure 2.

Frequency of publication of the studies in the review by year.

The consequences of the “Great Recession”, which affected all professional sectors all over the world, may be one of the reasons for the growing research interest in analysing the competencies that improve employability in the areas that demand high qualifications.

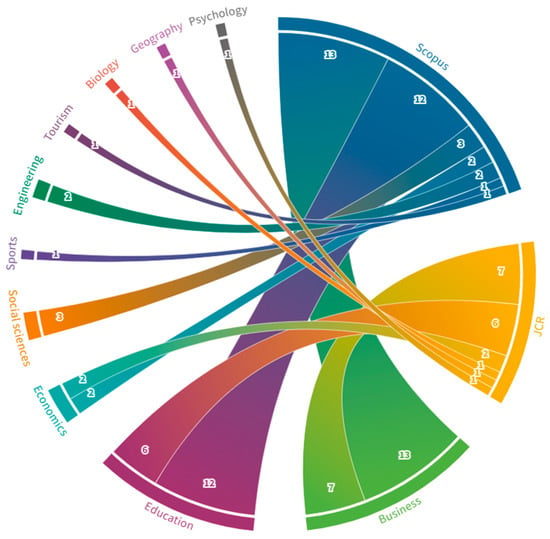

We also performed a relational analysis between the knowledge area and the journal impact factor (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Knowledge areas by journal impact factor.

There were more publications from the Scopus database (n = 34), with Business (n = 20) and Education (n = 18) being the knowledge areas with the most publications. There was a balance between Education, Business, and Economics in Scopus and JCR. In contrast, there were publications in the areas of Social Sciences, Sports, Engineering, and Tourism only in Scopus, whereas Biology, Geography, and Psychology were found only in JCR.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Employers and Organizations Hiring Graduates in the Reviewed Studies (RQ1)

In order to describe the characteristics of the employers, we analysed the personal (country, gender, age, and qualifications) and professional (years of experience, position, professional sector) dimensions.

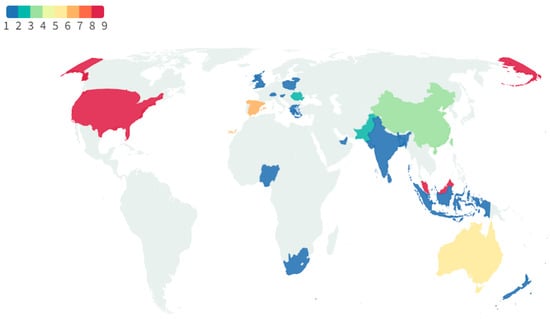

The initial analysis of the personal dimension showed that most of the studies took place in the United States (9), Malaysia (8), and Spain (6). Almost half of the sample of employers came from these regions in the cross-national context (see Figure 4). The distribution by continent was as follows: Asia (17), Europe (14), America (9), Oceania (6), and Africa (3).

Figure 4.

Worldwide distribution of employers in the studies. The samples in three of the studies included employers in various geographical regions, and therefore they were not included in the cross-national analysis.

Continuing with the analysis of the sociodemographic variables, we observed that there was little attention paid to the employers’ gender, age, or qualifications. Bearing in mind that these variables determine their belief systems, this may indicate a bias in the evaluation of transversal competencies.

Only a quarter of the studies (13) refer to the gender variable. In 70% of these studies, the majority of the employer samples were men. The other 30%, where women were the majority, were in traditionally female sectors. In terms of age, only seven studies indicated this variable, with 30–50 years being the most commonly reported age range. Lastly, only five studies noted that most employers had bachelor’s degrees or higher.

A second analysis, which focused on the professional dimension, showed that the employer sample had moderate experience, of at least five years on the job. Nonetheless, once again these data are open to more exploration, as few studies (5) looked at this variable.

In terms of the employer occupations, Table 1 shows that the greatest number (42%) were company managers or human resources managers. There were also a number of studies that report mixed profiles of occupations, with 15.4% combining company managers, human resources managers, and human resources staff. That said, it is worth noting that many of the studies (36.5%) did not include this information. This reflects the scant concern in the literature with regard to analysing how the positions of employers determine their belief systems [22], and thus their decision-making in the hiring process.

Table 1.

Employers’ positions in the studies analysed.

Table 2 indicates the most commonly represented sectors, which were professional, scientific, and technical activities (25%), manufacturing (13.5%), information and communication (7.8%), and financial and insurance activities (7.8%). However, the highest percentage were studies that looked at miscellaneous professional sectors (28.8%). In general, university graduates usually enter professional sectors that are highly qualified.

Table 2.

Employers’ professional sectors in the studies reviewed.

In terms of the types of organizations, there was again evidence of little concern about including this variable. Only 57.5% of the studies mentioned whether their samples of organizations were public or private. In addition, even in those studies that used private companies, almost half (43.3%) included public institutions in their analyses. This may be due to the easier access to samples of the employers in the public sector. Because of the nature of the sectors, the assessments of the required competencies by public sector organizations may well be different to those of businesses in the private sector.

Looking at the sizes of the businesses, there were many microbusinesses and small businesses. This may be a strength of this review, as these types of organizations are the most common at the global level. That being said, this variable was not often considered, and it only appeared in a minority (21.2%) of the studies. The studies did not use the standardized classifications of the business size, such as the one established by the OECD [63].

4.2. Prevailing Research Instruments, Techniques, and Validated Classifications Used to Assess Transversal Competencies (RQ2)

The review shows that the most widely used methods for assessing employability skills were indirect (75%). The employers evaluated transversal competencies via inferred information (which focused on the importance, the indicators of employability, or the expectations of the competencies required for the job) [3]. In contrast, only 25% of the studies conducted any direct evaluation of the skills required for the job (by focusing on the assessment of the hiring criteria by asking employers). In this direct evaluation, there were a large number of studies that focus on the analysis of the contents of job advertisements.

With regard to the techniques and instruments that were used for assessing the transversal competencies (see Table 3), the most common were questionnaires (71.1%), or questionnaires in combination with other data collection tools (15.4%).

Table 3.

Data collection instruments and techniques in the studies reviewed.

Overall, 84.6% of the studies included a scale for evaluating transversal competencies. These were generally Likert-type scales, with ranges from 2 to 10, although the majority used 5-point scales (54.5%). We also identified four classifications of transversal competencies that were recognized in the literature and by international institutions: Tuning [52], CHEERS [53], SCANS [55], and the USEM model [56]. Nonetheless, most of the studies used independent classifications, which makes an international comparison much more difficult because of the wide range of labels that are used for the competencies.

4.3. Most Commonly Reported Transversal Competencies by the Included Papers: A Classification Proposal (RQ3)

One of the key points of our analysis was to examine the most commonly reported soft skills in the scientific literature, and one of the main aims of the review was to identify, define, and classify those skills. We created a unified classification of 41 transversal competencies from the labels that were gathered from the reviewed studies, and we grouped them into five different dimensions: Job-related basic (JRB) skills, Self-management (SM) skills, Socio-relational (SR) skills, Entrepreneurship (ENT) skills, and social and professional responsibility (SPR) skills. Table A2 (Appendix B) presents a description of each competency, including the different names and labels that are used in the literature. A proposed classification of the transversal competencies that resulted from the systematic review is given below (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Classification of the transversal competencies analysed by the reviewed studies.

The first dimension, Job-related basic (JRB) skills, groups the knowledge and skills that are needed to effectively perform the job and ensure business productivity. This is the traditional dimension of employability that HEIs have concentrated their efforts on, with study plans that encourage the acquisition of knowledge and skills from a decidedly vocational “professionalization” approach, which facilitates the future graduates’ readiness for work [4,18,64].

The second dimension, Self-management (SM) skills, covers the essential skills that allow graduates to manage themselves and to operate self-sufficiently in their professional and personal lives. It is a key dimension, as it allows graduates to adapt to the socio-professional world and to make decisions throughout their lives [1,7,15,18,21]. This dimension underscores the need for university graduates to approach employability for boundaryless careers in the face of the complexity of the modern job market and social environment [29,30]. It also highlights the importance of “professional identity”, which is the way in which individuals are seen, and the way in which they see themselves, in social and professional settings [7,19]. This dimension corresponds to a person’s ability to learn to learn, and it is one of the weak points in the educational offerings of HEIs, which should use their institutional policies to articulate experiences that show that learning is a continual, life-long path [18].

The third dimension, Socio-relational (SR) skills, addresses the fundamental skills for responding to situations and contexts that require compromise, agreement, and understanding in global environments. It includes competencies that are focused on working in teams and that are aimed at achieving social engagement, which is only possible through actions that pursue common goals in various socio-professional settings [14,65]. Given how important this is, HEIs should encourage co-operative learning in university education as a strategy to improve graduate employability [66].

The fourth dimension, Entrepreneurship (ENT) skills, stands out in the policy agenda, as there are frequent references to the need to have entrepreneurial graduates. Clearly, these are essential skills for work, as leadership, initiative, and creativity drive innovation in a knowledge economy [67]. This means that it is important for HEIs to include specific programs in their plans of study that are aimed at improving graduate entrepreneurship, as this is a key dimension of employability [67,68].

Finally, the fifth of the dimensions, Social and professional responsibility (SPR) skills, is about the need to train people who can be committed and socially responsible in the face of the discrimination and social injustice that characterizes a competitive individualistic society. This dimension is linked to the discourse in HEIs where there are more and more educational activities and approaches, such as service-learning, which is aimed at promoting social responsibility and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals [69,70].

Looking at all of the transversal competencies together, the most commonly collected for assessment were, in order of frequency, SR1, JRB1, JRB2, ENT1, SM1, JRB3, SM2, SR2, SM3, SM4, ENT2, SPR1, and SM5. This shows that the JRB dimension is essential for graduate employability. Logically, the fact that they are fundamental to performing the job makes them indispensable for employers. Following that, the SM dimension was also well represented, although to a lesser extent. Problem solving (SM1), flexibility (SM2), analytical ability (SM3), lifelong learning (SM4), and critical thinking (SM5) are the necessary skills for graduates that will allow them to face the challenges of a complex and unstable job market.

Although a number of studies collected information about working in teams (SR1), leadership (ENT1), interpersonal skills (SR2), creativity (ENT2), and ethical working (SPR1), most of the components of the dimensions they belonged to (SR, ENT, and SPR) were scarcely mentioned. This suggests that, despite their professional and social importance in a globalized labour market, they remain in the background in the literature. Examples include the ability to work in an international context (SR9), networking skills (SR8), taking risks (ENT5), and gender awareness (SPR8).

4.4. The Transversal Competencies Employers Valued Most in the International Context, According to the Reviewed Studies (RQ4)

Starting from the classification of the transversal competencies above (Table 4), we reviewed which of them employers had identified as the most important in terms of graduate employability. We performed a general analysis first, in order to determine which competencies were most highly valued in the international context, and then we performed the analysis, which included the continent variable. The competencies that were most important to the employers are listed in Table 5. For a more in-depth analysis, we compared the percentages of the most highly valued competencies and the frequencies with which they were included in the studies, according to the data in Table 4.

Table 5.

Top 10 most important transversal competencies for employers in the cross-national context.

There was a clear relationship between inclusion and value, except for ethical working (SPR1). As already noted, the dimension of Social and professional responsibility (SPR) skills that contains this competency was the one that received the least amount of attention from the literature. Despite this, this result should be taken with caution, as even though it was not often collected, it was in the Top 10.

There were also three competencies that were often included in the studies, but that employers did not value so highly: leadership skills (ENT1), creativity and innovation skills (ENT2), and critical thinking skills (SM5). The first two of these, which are part of the Entrepreneurial (ENT) skills dimension, were particularly surprising. In a labour market with a high risk of automation, where one of the key factors for employability is the ability of the worker to lead and propose creative and innovative solutions [71], one might have expected the employers to value these skills very highly. The low valuation of the third skill is also an important finding, as, in the knowledge society, people must be able to assess the veracity of information and avoid possible bias.

The competencies that were less valued and less often included in the studies included those that refer to working in culturally diverse contexts (SR7), emotional competency (SM13), social responsibility (SPR5), and networking skills (SR8). This indicates that employers focus on the skills that are related to a candidate’s fit to the job, and that are aimed at promoting better productivity, and they focus less on the skills that involve the workers’ personal and professional growth.

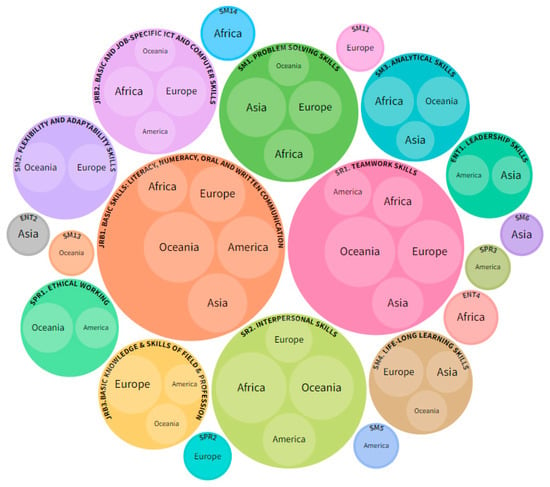

We continued by analysing the most highly valued transversal competencies by continent (see Figure 5) in order to determine the similarities and differences in how they were valued, according to geographical region.

Figure 5.

Transversal competencies that employers valued most by continent.

The figure above shows that some of the competencies were important in various continents, whereas others were only specifically required in one. On the basis of these results, we can highlight a series of transversal competencies that are valued by employers in various geographical regions:

- Transversal competencies that are important on 4–5 continents: These deal with the basic job performance (JRB1, JRB2), the effective interaction with teams (SR1, SR2), and problem solving (SM1).

- Transversal competencies that are important on 2–3 continents: These refer to autonomous learning and the adaptability to a changing labour market (SM2, SM3, SM4), job-related knowledge and technical skills (JRB3), ethical working (SPR1), and leadership skills (ENT1).

- Transversal competencies that are important on 1 continent: These are linked to the specific behaviours of the different economies in each continent, such as: the ability to put theory into practice (SM11) and responsibility (SPR2) for Europe; the ability to manage one’s own career (SM14) and an enterprising spirit (ENT4) for Africa; critical thinking (SM5) and a professional attitude (SPR3) for America; information management skills (SM6) and creativity (ENT2) for Asia; and emotional intelligence (SM13) for Oceania.

Analytical skills (SM3) and basic knowledge and skills related to the field and the profession (JRB3) are also worth mentioning. The former appeared in the Top 10 in Africa, Asia, and Oceania, whereas the latter was common to Europe, America, and Oceania. Other relevant findings include leadership skills (ENT1), which only appeared to be highly valued in America and Asia; flexibility and adaptability (SM2), which are valued in Oceania and Europe; and ethical working (SPR1), which is valued in Oceania and America. Oceania was notable, with the presence in 11 of the 12 groups of the competencies in Figure 5.

5. Discussion

This article aimed to illustrate how transversal competencies are estimated from the perspective of employers in the international context. More specifically, we examined the characteristics of the employers and the work-related requirements in those economic sectors that require high levels of qualifications [72]. The study has given us an overall picture of the academic literature on this subject, especially in relation to the publications by geographical region, the study variables, and the methods that were used to evaluate the competencies.

It is worth noting, first, that the studies that we reviewed were not equally distributed geographically. There were fewer studies published in certain regions, which corresponds to the findings that link the journal impact factors with the limitations for authors from non-English-speaking countries [73]. Although indexing papers provides some assurance of the quality of the publications and advances the results, it also means the under-representation of certain parts of the world [14].

One notable concern that was raised by the analysis of the employers who hire graduates at the international level (RQ1) was that very few studies identify the employers’ sociodemographic (gender or background) or professional (position) variables. These are questions that deserve particular attention because of their links to the power relationships in the workplace [74,75].

Women were seen to be under-represented in management positions, which may mean bias in the evaluation of the competencies [76], while workers often related good management with predominantly masculine characteristics [77]. Similarly, the literature indicates that, during the hiring for low-power roles, men can react negatively to female applicants as they perceive them as threatening [74]. Gender bias in hiring decisions, which particularly affects male-dominated occupations, such as engineering and IT, may have negative consequences in terms of salary, progression, professional status, and personal life [75,78,79].

Considering the impact of individual employer characteristics and belief systems on hiring processes [22], researchers should examine this issue more deeply, and should avoid biases in the interpretation of information. This should also be extended to the profiles of the graduates that organizations hire, as, when looking at the hiring process, gender and origin are the variables that may be associated with increased discrimination [48,74,79,80]. In this regard, international scientific authorities recommend that more women should be on hiring committees to reduce the biases in the skill requirements during hiring [75,81].

The same happens with the organizational characteristics (RQ1), as the review also shows that there is little concern in the literature for identifying the sizes or types of organizations, or the professional sectors that employ graduates. This is another significant challenge because the variables that are related to the organizational or institutional context determine the level of importance that employers place on the soft skills [47]. In this regard, it was concluded that, in the European context, large international organizations have greater requirements for competencies, which is why we can talk about “reputational recruiters” [37].

Most of the studies that are included in the review used indirect methods to assess the transversal competencies from the employers’ perspectives (RQ2). This is an issue that requires some caution, as the direct methods, such as the analysis of the job requirements, mean that there is greater objectivity for the evaluation compared to indirect methods, which are focused on assessing the satisfaction, importance, or expectations of the graduate skills, which calls for employers to make more subjective assessments [3].

In recent years, there has been growing interest in incorporating validated scales into the evaluation of employers’ skill requirements. According to the results of our review, this is an issue that the scientific literature should take greater note of, as more inclusion or less inclusion of competencies can determine how they are assessed: if a competency “doesn’t exist”, it cannot be evaluated [82].

Given the wide range of scales that were used in the studies we reviewed, it is reasonable to conclude that there is a need to move towards defining consensus scales that will allow for an international comparison, and to avoid the mismatch between what universities provide and what businesses require [3]. In fact, the lack of international classifications was one of the main reasons behind our objective of identifying and classifying the transversal competencies (see Appendix B), which follows on from the research efforts of the other systematic reviews on the subject [14,34,58,59].

One of our most important findings in this regard was the clarification of the grouping of the dimensions of the “soft skills” for graduate employability in the international context (RQ3). From this, we examined the competencies that employers valued most highly (RQ4), and we found various results that merit discussion here. It is important to note that, although we were able to identify some of the skills that were highly sought after in all of the sectors and geographical regions, there were large differences in the considerations of the different dimensions.

In part, this may be because there are certain contextual variables that mediate the importance that is placed on the skills that are needed for a job. The need for any given competency has been shown to be strongly affected by the employers’ economic policies and belief systems [37,72], which may underlie the differences that we found in the systematic review. However, research into the contextual factors and what they mean for the assessment of transversal competencies is a line of analysis that is still in its early stages [14].

As we have seen, the three competencies that make up the dimension of Job-related basic (JRB) skills were highly valued. In a globalized economy such as ours, it makes sense for digital skills to be highly sought-after [83,84]. We saw the same with communicative skills, which employers have also indicated as fundamental for graduate employability in other systematic reviews on the subject [14,34,59]. In a similar way, we found studies that justified the high value that is placed on the competencies that are related to specific job-related knowledge, which indicates that graduates should have skills that are related to their occupation [85], as well as be able to apply specific subject knowledge [86].

Given how important this dimension is in the process of entering the job market, there is a need to understand how teaching practices can contribute to developing it and making it into a potential core activity in HEIs. Following the same line, various studies have highlighted the importance of work experience in preparing university students in real workplace settings, as it encourages contact with reality and promotes opportunities to develop this group of skills [14].

In terms of the dimension of Self-management (SM) skills, we found that employers valued problem solving, life-long learning skills, flexibility and adaptiveness, and analytical skills. This is consistent with the current occupational guidance, which demands workers who can adapt to changing job markets [7,24]. This dimension of competencies requires exactly that self-awareness of personal skills, which allows for movement in evermore uncertain social and occupational settings [1,15].

In this regard, career management has become an important skill, as it allows subjects to guide their own professional pathways in a constantly evolving job market [18,19]. Despite this, our review shows that the employers did not place great value on competencies such as career management skills. In the current job market, this is fundamental from the point of view of multidirectional career pathways, in which graduates must know how to consistently direct their professional lives [30]. However, businesses seem more interested in the competencies that help subjects to behave appropriately and effectively in difficult situations and deal with a complex labour market—the "professional development competencies”, according to Bridgstock [7]—but they are less invested in the competencies that are focused on career management.

The competencies that the employers valued most highly in the Socio-relational (SR) skills dimension were teamwork and interpersonal skills. Our results are consistent with the results from the systematic reviews by Abelha et al. [14], Fajaryati et al. [34], and Sarfraz et al. [59], in which the ability to work in a team appeared as one of the most highly valued competencies by employers. It is clear that the current labour market is characterized by roles that need high levels of social interaction skills [5,15,35]. However, the scientific literature also pays particular attention to the influence of factors (such as the effect of social capital on employability) that are directly related to interpersonal competencies [37].

In this same dimension, we found that there is little value placed on competencies such as foreign language skills, the ability to work with diversity and multiculturality, and the ability to work in an international context. This is in line with the results from Sarfraz et al. [59], who report that global citizenship skills and the skills that are needed for working in multicultural contexts were not considered important by employers. It is surprising that, in such an interconnected economy, which demands evermore mobility and internationalization as the essential factors in training and capturing talent, this group of competencies is not considered so important. In fact, it has been shown that, in favourable conditions, experiences of mobility can have a signalling effect on hiring decisions, which reflects a specific personality and skill set that employers appreciate [87,88,89].

On a different note, the competencies that make up the Entrepreneurship (ENT) skills dimension were generally not highly valued, despite being assessed in a notable proportion of the studies that we reviewed. This is in contrast to the fact that entrepreneurship has become an important topic for the scientific literature, as many studies have determined its influence on the processes of entering the world of work [71,90,91]. Nowadays, entrepreneurship boosts both the promotion of employment and the dynamization of economies, as it allows subjects to recognize job opportunities and to generate innovative ideas and projects [92].

One of the competencies in this dimension that stood out was leadership, as it was more highly valued than the others, although it did not reach the Top 10. It is very common to find studies in which leadership skills are linked to entrepreneurial skills, with the understanding that they allow people to motivate, persuade, and guide others towards specific objectives [93].

Our review shows that, for the final dimension, Social and professional responsibility skills (SPR), studies indicated high value placed on the ethical working competency. Ethical working, and similar values, have become key components in the modern job market. Consistent with this, at the international level, is a clear and growing concern for universities to prioritize educating responsible citizens who have social consciences, and who are able to perform their work from a perspective of ethical engagement [94,95,96].

It is clear that graduate employability has become a great challenge for higher education. As we have seen, the socio-occupational framework in which the professionalizing dynamic of universities has become prominent is characterized by rapid changes that are based not only on economic circumstances, the jobs on offer, or the demands of work, but also on the attitudes, abilities, and social factors that are key for employability.

As a consequence, HEIs have to adapt study plans with what has been called, “pedagogies for employability” [12,13], with consideration to those core competencies that are more likely to be highly valued by employers. This means opening up universities to the outside world and involving society and the economic world in the educational process. In other words, universities must take advantage of, and provide graduates with, knowledge of the immediate surroundings, which means that the creation of curricula must consider the specific demands that the job market has for them.

6. Conclusions

With this study, we provide a systematic review of university graduates’ transversal competencies and employability. The paper has two main issues of interest. One is the identification of the transversal competencies that employers value most highly in the cross-national context. The other is the definition of a unified classification that may contribute to future studies about the evaluation of transversal competencies, especially given the lack of consensus in the literature in terms of the terminologies, definitions, and importance.

This classification will enable the comparison of this group of competencies in international research, and it will also serve as a mechanism for the assessment and monitoring of student learning in universities. It could, therefore, be an instrument for quality improvement in HEIs, evaluation agencies, and public policy. It may also be a significant contribution to unemployed young people or adults and those transitioning into work, as it allows the changes in the competency requirements to be seen during the time frame that is covered by the study.

We conclude that universities still have work ahead of them in improving the employability of their graduates. HEIs should move away from a solely vocational or professionalizing approach towards one that helps to provide graduates with the personal resources they need for personal and professional development over their whole lives. In this regard, there are clear limitations to the current study plans when it comes to helping graduates face multidirectional professional pathways. It is in this context that the “pedagogies for employability” makes the most sense, by allowing universities to include active methodologies in the education they offer, and by strengthening the links between academia and the socio-occupational reality.

As with all research, this systematic review has limitations. In particular, the variety of the classifications that are used in the studies we reviewed was a challenge for the analysis of the competencies that the employers valued most highly. In this regard, the classification of the transversal competencies that we produced allows us to resolve this issue by integrating the various labels into a single approach, which is structured in five large dimensions of employability.

Another limitation is the lack of agreement about which variables affect graduate employability, which made a comparative analysis of this topic impossible. This was the case for variables such as the employer characteristics (gender, age, background, professional experience, etc.) and the organizational characteristics (professional sector, ownership, size, location etc.). Even though these variables have been identified as determinants in the literature, they were not sufficiently collected in the studies that we reviewed to allow generalizable conclusions to be drawn. There is no doubt that research should continue to move forward, and that it should include and analyse these variables in order to offer a more realistic view of university graduates’ transition to work.

At the prospective level, the aim is to continue this line of research by validating the proposed classification of the transversal competencies. This would allow for studies about the development and acquisition of these competencies, and it would encourage follow-ups of the students’ education by professionals, HEIs, and assessment agencies. In addition, it would allow for comparative analyses between the education that universities offer and the demands of the job market, and for the identification of potential skill mismatches, and the need for academia to take preventive or corrective action.

This study clearly contributes to the topic of graduate employment in competency terms. We must not forget that, nowadays, graduates face high levels of occupational uncertainty, which translates to high rates of unemployment, low salaries, overqualification, temporary contracts and, in short, precarious and fragmented professional careers. This issue, in the framework of the third mission of HEIs, must lead to efforts to accompany and guide graduates on one of the most critical stages of their lives: the transition to work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.-Á., A.V.-R. and A.Q.-C.; methodology, J.G.-Á., A.V.-R. and A.Q.-C.; software, J.G.-Á., A.V.-R. and A.Q.-C.; formal analysis, J.G.-Á., A.V.-R. and A.Q.-C.; investigation, J.G.-Á., A.V.-R., A.Q.-C. and D.P.C.; resources, J.G.-Á., A.V.-R. and A.Q.-C.; data curation, J.G.-Á., A.V.-R., A.Q.-C. and D.P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.-Á., A.V.-R. and A.Q.-C.; writing—review and editing, J.G.-Á., A.V.-R. and A.Q.-C.; visualization, J.G.-Á., A.V.-R. and A.Q.-C.; supervision, J.G.-Á., A.V.-R., A.Q.-C. and D.P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of the studies included in this review.

Table A1.

Summary of the studies included in this review.

| ID | Reference | Country | Focus | Methodology | Sample | Professional Sector |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jurše and Tominc, 2008 [97] | Slovenia | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (4-point scale) | n = 63 (company managers) | Wholesale and retail trade; vehicle repair. |

| 2 | Hernández-March et al., 2009 [98] | Spain | Assessment of competences required | Questionnaire (5-point scale) and interviews | n = 872 (executives, human resources managers, and staff of the human resources department). Private sector. Company size: large (55%); medium (30%); small (15%). | |

| 3 | Rahmat et al., 2015 [99] | Malaysia | Assessment of competences required | Interview (2-point scale) | n = 5 (human resources officers) | Electrical and electronics industry |

| 4 | Moczydłowska and Widelska, 2014 [100] | Poland | Assessment of competences required | Questionnaire (5-point scale), discussion group, and interview | n = 120 Company size: small (47%); self-employed individuals (44%). | Machinery sector |

| 5 | Fominiene et al., 2015 [101] | Lithuania | Demand | Questionnaire (4-point scale) | n = 64 Gender: 83% women and 17% men. Experience: more than 5 years (75%); 1–5 years (25%). | Tourism |

| 6 | Jaaffar et al., 2016 [102] | Malaysia | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (2-point scale) | n = 105 | Manufacturing (47.6%) and service sectors (52.4%) |

| 7 | Dunbar et al., 2016 [103] | Australia | Assessment of competences required | Content analysis (job advertisements) | n = 1594 (job advertisements) | Accounting |

| 8 | Chaplin, 2016 [104] | Australia | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (2-point scale) | n = 143 Private sector. Company size: principal only (4.2%); 1–5 employees (52.4%); 6–20 employees (27.3%); 21–100 employees (13.3%); 101–500 employees (2.8%). | Accounting |

| 9 | Al Shayeb, 2013 [105] | United Arab Emirates | Assessment of competences required | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 145 | Finance, manufacturing industry, services, and other sectors. |

| 10 | Rasul et al., 2013 [106] | Malaysia | Assessment of competences required | Questionnaire | n = 107 | Manufacturing industry |

| 11 | Su and Zhang, 2015 [107] | China | Indicators of employability | Questionnaire and interviews | n = 100 State-owned enterprises and government institutions (21%); overseas-funded enterprises (26%); individually run enterprises (34%); administrative agency (13%); and others (6%). | Manufacturing industry (15%); transportation industry (14%); banking and insurance business industry (21%); international trade industry (12%); research and technological service (9%); construction industry (4%); real estate industry (4%); education, culture, and television industry (5%); and public organization (3%). |

| 12 | Rizwan et al., 2018 [108] | Pakistan | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 129 Gender: 71% male and 29% female. Hiring experience: 3–6 years (32%); 7–9 years (46%); more than 10 years (32%). Multinationals (25%); public sector (43%); and private sector (32%). | Engineering sector: telecom (26%); electrical/electronics (21%); civil (11%); mechanical/industrial (19%); chemical/petroleum (7%); and computer/software (16%). |

| 13 | Abbasi et al., 2018 [109] | Pakistan | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 121 (company managers). Gender: 93% male and 7% women. Age: 27–58 years (mean age: 39 years). Education: 70% having 16 years of education. | Financial and insurance activities |

| 14 | Hamid et al., 2014 [110] | Malaysia | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 233 (human resources managers, 54.7%; top management, 43.2%; middle, 2.1% lower). Gender: 48.1% male and 51.9% female. Age: 30 years or below (19.9%); 31–40 years old (22.5%); 41–50 years old (38.5%); 51 years old and above (19.1%). Qualification: diploma (18.8%); bachelor’s (54.4%); master’s (20.6%); PhD (3.5%). Experience: 5 years or less (37.6%); 6–10 years (24.9%); 11–15 years (12.2%); 16 years or more (25.3%). Private companies, government agencies, and semigovernment agencies. | Manufacturing industry |

| 15 | Deaconu et al., 2014 [111] | Romania | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 92 (55.4% human resources managers, and 44.6% management staff in the human resources department). Average time of service: 6.3 years. Qualification: bachelor’s (53.2%); master’s (42.4%); did not complete higher education (4.4%). Limited liability companies (59.8%); joint stock companies (25%); and state institutions (15.2%). | Trade; manufacturing (clothing, footwear, furniture, wire-based products); consultancy; telecommunications; constructions; real estate; education; tourism; and transport. |

| 16 | Sodhi and Son, 2008 [112] | United States | Demand | Content analysis (job advertisements) | n = 1056 (job advertisements) | Industry sector: computer services; banking; consulting; marketing; and IT. |

| 17 | Baker et al., 2017 [113] | United Kingdom, France, Germany, Spain, Greece, and the Czech Republic | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 327 (60.2% senior managers/executives/senior academics; 26.5% managerial staff; and 13.3% sports instructors, sports coaches, or human resources managers). Gender: 70% male and 30% women. Mean age: 42.5 years. Private business (54.8%). | Sports sectors; retail/commerce; health/medicine/social care; education; and public services. |

| 18 | Chen et al., 2018 [114] | Australia, United States, Canada | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale), interviews, and discussion group | n = 117 employers (24.3% division managers; 17.1% functional managers; 14.4% managing directors; 14.4% resource managers; 13.5% managers; 5.4% chief executives; 11.7% other) +27 senior industry managers. Private sector. | Maritime industry |

| 19 | Ramadi et al., 2015 [115] | Countries of the Middle East and North Africa | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (10-point scale) | n = 132 (company managers) | Engineering sector |

| 20 | Dhiman, 2012 [116] | India | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 520 (human resources managers). Gender: 76% male and 24% women. Private business. Company size: 101–300 employees (37.5%); 301–500 employees (27.9%). | Housing and food services |

| 21 | Suarta et al., 2018 [117] | Indonesia | Demand | Content analysis (job advertisements) | n = 57 (job advertisements). Multinational companies. | Information and communication |

| 22 | Ahmed and Khasro, 2016 [118] | Bangladesh | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 174 (company managers). Totals of 12 multinational and 8 local companies. | Human resources management |

| 23 | Lim et al., 2016 [119] | Malaysia | Importance of skills | Questionnaire | n = 53 (human resources managers: 80% recruitment and selection of entry-level employees). Private sector. | Accounting |

| 24 | Tsitskari et al., 2017 [120] | Greece | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 193 (company managers). Gender: 72.5% male and 27.5% women. Age: 40–49 years (45.1%); 50 and older (24.3%). Public and private enterprises. | Sport and recreation sector |

| 25 | Plaias et al., 2011 [121] | Romania | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 171 (50.3% administrators; 30.4% general managers; and 19.3% people responsible for marketing) Qualification: bachelor’s (50.3%); postgraduate degree (39.8%). Age: 41–50 years (33.9%); 31–40 years (29.2%); under 30 (19.9%); over 50 years old (17%). Private sector. | Economy and marketing: production companies (25.1%); commercial enterprises (30.4%); financial services (9.4%); tourist services (4.7%); others (25.1%). |

| 26 | Ghani et al., 2018 [122] | Malaysia | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 187 (company managers). Private sector (53.5%), and public sector (46.5%). | Accounting |

| 27 | Pita et al., 2015 [123] | Switzerland | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 67 (47 university staff, and 20 representatives from research institutes and industry). Gender: 65.1% male and 34.9% female. Average age: 47 years. Private and public sector. | Aquaculture, fisheries, and other marine sectors. |

| 28 | Mohd et al., 2016 [124] | Malaysia | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 43 (27.9% managing directors/chief operations officers; 30.2% engineers/architects; 27.9% human resource officers; and 14% others). Private sector. | Industrial: civil and environmental engineering (23.3%); electronic and electrical engineering (14%); mechanical and manufacturing engineering (14%); all the above (25.6%); and others (23.3%). |

| 29 | Teijeiro et al., 2013 [125] | Spain | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (7-point scale) | n = 907. Private companies. Company size: less than 10 workers (46.1%); 10–49 workers (33.6%); 50–249 workers (15.8%); more than 250 workers (4.5%). | Biohealth area; humanities; sciences; engineering; and social sciences. |

| 30 | Clokie and Fourie, 2016 [126] | New Zealand | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (6-point scale) | n = 30 (senior managers). Private companies. | Industrial: communication; media; finance; public relations; local government; dairy and agriculture; IT; creative industries; event management; sports; health sector; retail; and advertising. |

| 31 | Pitan, 2017 [127] | Nigeria | Importance of skills | Questionnaire | n = 421 (staff from the human resources department). | Manufacturing; construction; mining; agriculture; forestry; health; education; and banking. |

| 32 | Wikle and Fagin, 2015 [128] | United States | Importance of skills | Questionnaire | n = 197. Qualification: more than 90% hold a bachelor’s degree or higher. Public sector: government (83%). | Professional, scientific, and technical activities. |

| 33 | Ho, 2015 [85] | Taiwan | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 95 (human resources managers). Gender: 74% male and 26% female. Private companies. | Agriculture (12%); education and arts (13%); construction and engineering (35%); and business (40%). |

| 34 | Jonck and Van der Walt, 2015 [129] | South Africa | Assessment of competences required | Questionnaire (4-point scale) | n = 503 (public sector: 84.8% human resources managers or line managers; private sector: 65.6% human resources managers or line managers). Gender: 56% male and 44% female in the public sector; 58.5% male and 41.5% female in the private sector. Public and private sectors. | Finance and banking; construction; logistics and transportation; hospitality; service delivery; and miscellaneous industries. |

| 35 | Cegielski and Jones-Farmer, 2016 [130] | United States | Importance of skills | Delphi technique, content analysis, and questionnaire (7-point scale) | n = 160 (company managers). Private sector. | Business analytics and financial services. |

| 36 | Marzo-Navarro et al., 2008 [131] | Spain | Assessment of competences required | Questionnaire (7-point scale) | n = 144 (human resources managers and general managers). Gender: majority were men. Age: 20–25 years old (45.8%). Private companies. Company size: less than 50 workers (61%); 50–250 workers (18.6%); more than 250 workers (20.4%). | Service (59%) and manufacturing (40.2%). |

| 37 | Schlee and Harich, 2009 [132] | United States | Assessment of competences required | Content analysis (job advertisements) | n = 500 (job advertisements). | Marketing |

| 38 | Santana et al., 2016 [133] | Spain | Indicators of employability | Questionnaire (5-point scale) and discussion group | n = 292 Company size: 0 workers (2.1%); microenterprise (33.5%); small (36.3%); medium (22.6%); large (5.5%). | Construction (7.5%); industry (15.1%); tourism (17.1%); commerce (24%); and other services (36.3%). |

| 39 | Poon, 2012 [134] | United Kingdom | Employers’ expectations of graduates | Questionnaire and interviews | n = 75 (62 real estate employers; 5 course directors of RICS accredited courses; and 8 human resources managers). Private sector. | Real estate |

| 40 | Hayes et al., 2018 [135] | Australia | Importance of skills | Questionnaire and interviews | n = 12 (2 owners/sole practitioners; 1 human resources business partner; 1 chief operations officer; 4 partners; 1 accountant; and 1 senior manager). Private sector. Company size: less than 5 workers (25%); 6–20 workers (25%); 21–100 workers (50%). | Accounting firms |

| 41 | Rosenberg et al., 2012 [136] | United States | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (7-point scale) | n = 97 (human resources managers). | Business |

| 42 | Messum et al., 2017 [137] | Australia | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 38 (chief operations officers; general managers, or directors of health districts; organizations or services). Gender: 50% men and 50% women. Experience: had been employed in health for over 20 years. Public sector (55%); not-for-profit sector (35%); private sector (10%). | Health services management |

| 43 | Deming and Kahn, 2018 [138] | United States | Demand | Content analysis (job advertisements) | n = 44,891,978 (job advertisements). | Management; business and financial operations; computer and mathematics; architecture and engineering; the sciences; community and social services; legal; education; arts and entertainment; healthcare practitioners; and technical occupations. |

| 44 | Wesley et al., 2016 [139] | United States | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (7-point scale) | n = 29 (business leaders). Gender: majority were women. | Retailing and tourism |

| 45 | Velde, 2009 [140] | China | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (4-point scale) | n = 27 (company managers). Private sector. Small and medium enterprises. | Design or business companies |

| 46 | Chan et al., 2018 [141] | Malaysia | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (3-point scale) | n = 182 | Manufacturing industries |

| 47 | Kavanagh and Drennan, 2008 [142] | Australia | Importance of skills | Interview (5-point scale) | n = 28 | Accounting (professional services); commerce and industry; and government. |

| 48 | Wickramasinghe and Perera, 2010 [143] | Sri Lanka | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 26 | Software development |

| 49 | Frazier and Cheek, 2015 [144] | United States | Importance of skills | Questionnaire (5-point scale) | n = 109 (mid-level retail managers). Age: 21–30 years (48%); 31–39 years (21%); 40 years or older (31%). Experience: less than 5 years of retail experience (17%); 6–10 years (33%); more than 10 years (50%). Qualification: 93% had a college degree. | Textile: retail sector. |