1. Introduction

The Fulbright Program is the United States’ flagship international exchange program [

1]. The State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act 2022 [

2] recommended that

$275,000,000 be appropriated for the Fulbright Program. With this level of investment by the US government in an educational program housed in the Department of State rather than the Department of Education, scholars should examine the impact of this program on the internationalization of higher education. In other words, the Fulbright Program’s participation in encouraging scholar mobility to the United States through its visiting scholar program is highly relevant to internationalization overall, given the US’s hegemonic role in international higher education [

3].

Senator J. William Fulbright introduced legislation to establish the Fulbright Program in 1946 as a foreign policy effort that aimed to promote mutual understanding between the US and partner nations around the world [

4]. Under the Fulbright–Hays Act, the US and partner nations must establish a binational agreement that outlines the terms of the program in a particular country, making each program unique to the relationship between the US and that country [

1]. For example, some of the first binational agreements were between the US and wartime allies following WWII, such as Australia and China, in which the US agreed to alleviate wartime debt in exchange for the establishment of a Fulbright agreement [

4].

The number of visiting scholars in the United States has steadily increased in the past 20 years [

5]. The Fulbright Program fully funds approximately 850 post-doctoral visiting scholars from over 100 countries for periods of three months to a year. This paper advocates for explicit focus on Fulbright visiting scholars in the literature because, although they comprise a small portion of the total number of visiting scholars in the United States, the US government’s financial investment in them as a component of their foreign policy strategy deserves particular attention.

Furthermore, the nations of origin of Fulbright visiting scholars do not proportionally reflect the nations of origins of visiting scholars to the US in general [

5,

6], suggesting that this particular subset of visiting scholars may have some unique qualities. According to the most recently published Fulbright Annual Report (2016) [

6], the highest proportion of visiting scholars come from Europe, while the lowest proportion come from Africa, as demonstrated in

Table 1. These numbers reflect the historical total of Fulbright visiting scholars to the US, with Europe as the highest number and Africa as the lowest. On the other hand, visiting scholars to the United States largely came from China, India, and South Korea in the 2016–2017 academic year [

5].

Some research has been conducted to understand visiting scholars’ experiences to the United States in general. Empirical work that investigates visiting scholars’ experiences find that scholars’ negative experiences sometimes include unsatisfactory levels of institutional support and discrimination based on race and ethnicity [

7,

8]. Some positive experiences described in the literature include a strong sense of community among peers and colleagues at their American institutions, as well as long-lasting professional connections [

9,

10].

In this systematic review, it is argued that by synthesizing literature that explores Fulbright visiting scholars’ experiences, it illuminates the specific impact of government-sponsored scholarly exchange on the participants of these programs in the context of the United States, in ways that are both similar and different to the experiences of visiting scholars in general. This systematic review aims to examine how the experiences of Fulbright visiting scholars to the United States’ are represented in qualitative research, specifically examining which experiences scholars share regardless of their nations of origin.

2. Methods

2.1. Document Search

This study was conducted according to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Statement (PRISMA) [

11]. A search of the titles and abstracts of all article types was first conducted within the following databases: Google Scholar, Education Source, and ProQuest Education Journals. The following search terms were used for all three databases: (“visiting scholar” OR “visiting scholars”) AND (experience OR experiences) AND “United States” AND “Fulbright Program”. Bramer et al.’s [

12] method was used for developing literature searches in choosing these search terms, which involved the development of the research question, identifying search terms and their synonyms, and an iterative process in finding terms that would yield results appropriate for the research questions. These search terms helped to identify articles that related to specifically Fulbright scholars visiting the United States rather than US scholars visiting partner nations, and also specified that the articles should relate to the Fulbright program rather than visiting scholars in general. These three databases were chosen in order to elicit articles with sufficient quality from the field of education and a broader selection of articles from all fields with Google Scholar. These three databases also elicited results from international journals to ensure that the results were not limited in terms of country of publication.

The search was limited to the past 10 years (2011–2021). The same search terms were used within all of the databases, and the search was completed on 20 November 2021. Full details of the search strategy are provided in

Table S1, along with examples of articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria and were therefore excluded (

Supplementary Material).

2.2. Selection Criteria and Process

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) The full text was available in English; (b) the article was published in a peer-reviewed journal or was a thesis or dissertation, which underwent a basic level of peer review; (c) the article presented qualitative empirical data or historical analyses; (d) some or all participants or subjects of the study were faculty members working at non-US higher education institutions who were visiting scholars to higher education institutions in the United States; (e) the study included either some or all of its participants or historical subjects were Fulbright visiting scholars; and (f) the data collected related to a visiting scholar experience. Articles that were excluded included participants in the study that were exclusively faculty members at US institutions and were visiting scholars to non-US institutions and quantitative studies.

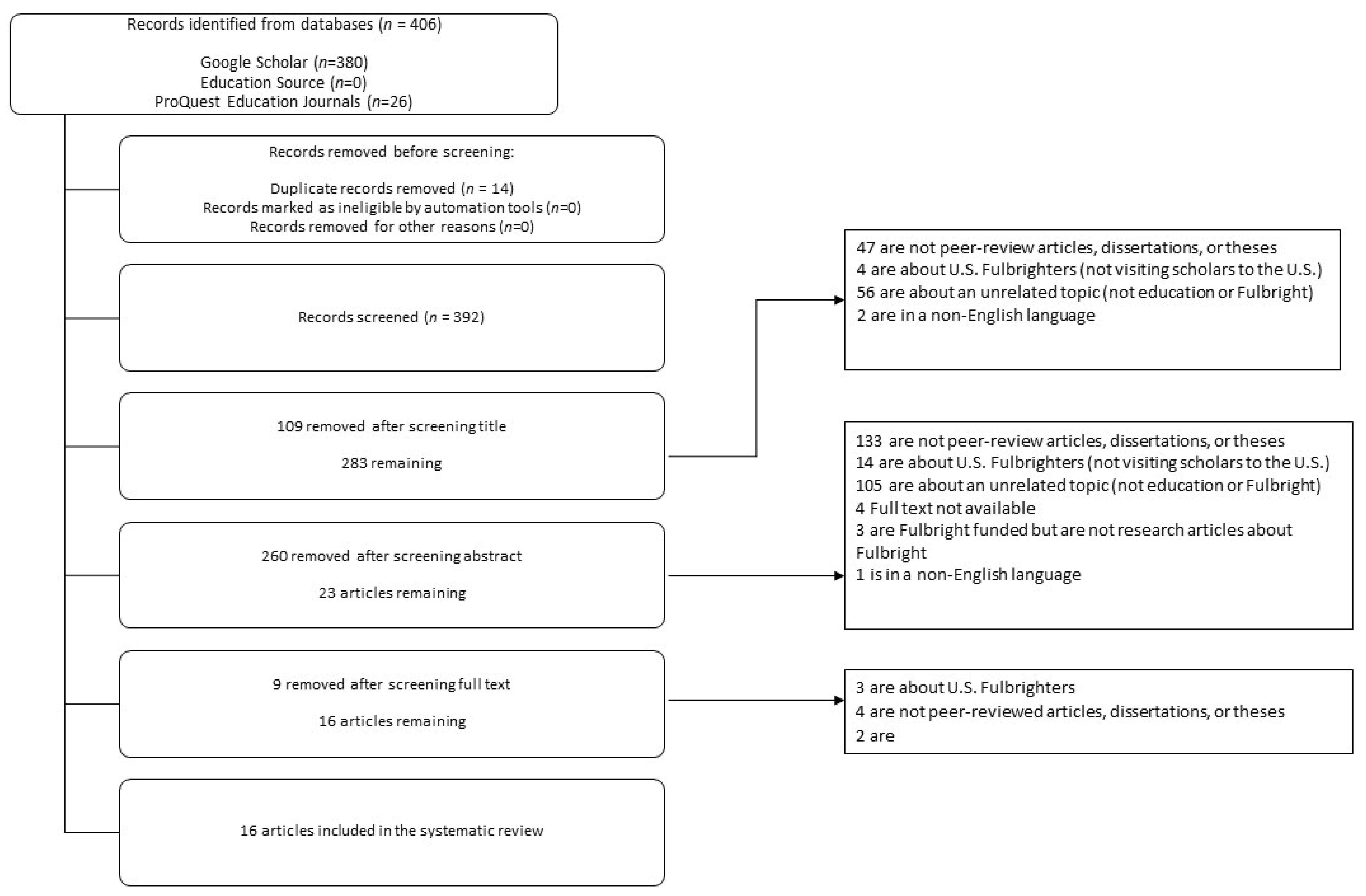

Each paper was manually screened at the level of title, then abstract, then at full text. Finally, the articles were then selected based on the inclusion criteria for the final data set. The details of this process are depicted in

Figure 1. A total of 14 duplicate records were removed, 184 records that were not peer-reviewed articles, dissertations, or theses were removed, 171 records that did not meet the criteria for content were removed, 4 records that were not available in full text were removed, 3 non-English records were removed, and 2 quantitative studies were removed when screening at the full text level. A total of 14 articles published in peer-reviewed journals, dissertations, and theses between 2011 and 2021 met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review.

Table S2 shows details of the articles that were selected for review, indicating all relevant information: Author, year, research design, and number of citations (

Supplementary Material).

2.3. Thematic Analysis

The open-source qualitative coding software, Taguette, was used to analyze the 14 studies included in the systematic review. Thomas and Harden’s (2008) [

13] method of thematic analysis of qualitative research in systematic reviews was used, which recommends a three-step process for coding literature: (a) Line-by-line coding of each article’s finding section, (b) development of descriptive themes, and (c) generation of analytical themes. They argue that explicit development of the themes is central to the method. Therefore, the entire codebook applied to the Taguette project, as well as information about the distribution of coding, is included in

Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials.

2.4. Confirmability and Dependability

The

Supplementary Material, which describe the search strategy, coding strategy, and the details of each included article are made available as a confirmability strategy [

14] to support the validity of the results. A summary of the final analytic codes is shown in

Table 2. To further support the validity of the results of this systematic review, peer debriefing was used with three critical peer reviewers, which was conducted by sharing the results and explaining the methods of the findings. The results were then reframed according to their conversation to ensure dependability of the research [

14].

2.5. Limitations

The analysis of this study is limited because articles included in the study are only in English, despite aiming to understand the experiences of non-US visiting scholars, many of whom publish research in non-English languages. Therefore, the home countries of the visiting scholars represented in these articles represent only a small number of the home countries of Fulbright visiting scholars. Future research may conduct the same systematic review and compare the results to gain a better understanding of how the experiences of Fulbright visiting scholars are represented in the literature, as well as include a multilingual search.

3. Results

The thematic analysis yielded two primary analytic themes from the data: (a) Participating in the Fulbright Program creates complicated relationships with the United States government and people; and (b) Fulbright visiting scholars experience administrative burden. The following section describes these results in greater detail and provides examples from the selected articles.

3.1. Participating in the Fulbright Program Creates Complicated Relationships with the United States Government and People

Fulbright visiting scholars have a variety of attitudes toward American cultural values, the American higher education system, and their experiences as Fulbright visiting scholars to the United States in general. Among the 14 studies included, 11 of them (78.5%) discussed the mixed feelings of Fulbright visiting scholars toward the United States. For example, Fu (2018) [

17] found that, in a qualitative study of Fulbright visiting scholars from China, participants celebrated some experiences of academic life in the United States (e.g., work ethic, autonomy, and socioeconomic diversity in the classroom), while still maintaining critical viewpoints of the United States government. Fu clarified that, in the case of Chinese Fulbright visiting scholars, satisfaction with the program and favorability toward the US were unrelated ideas.

The participants in Cheddadi’s (2018) [

15] study acknowledged that working and studying in the United States would afford them opportunities that they would not have had access to in Algeria, but they also argue that it is not the grant that positively changed their views toward American culture, but rather, media and other cultural exports that they consumed while living in Algeria. These participants argued that they could participate in a Fulbright grant and reap the benefits of the academic exchange without necessarily being influenced by American culture and values.

The articles included in this study often presented a juxtaposition with scholars’ critical viewpoints of the United States when they described how Fulbright visiting scholars’ participation in the Fulbright Program had an influence on their academic and professional life upon their return to their home institutions. Among the 14 studies included, 8 of them (57.1%) discussed the Fulbright Program’s influence on visiting scholars’ academic and professional lives. For example, Eddy (2014) [

16] found that Irish visiting scholars to the US noticed that interdisciplinary work was valued more in their US institutions than in Ireland, some scholars made an intentional effort to create a more interdisciplinary focus in their classrooms upon their return to Ireland. Bettie (2015) [

18] describes how a South African grantee continues to educate South African peers about American people and culture after the grant term was over. Leite and Gaia (2017) [

19] described how interactions with American students in the classroom influenced them to reflect upon cultural differences between American and Brazilian students in their field.

Bettie (2015) [

18] argues that, despite not having any contractual obligations as a diplomat, some scholars feel an unofficial sense of duty when accepting government sponsorship. Zhuk (2018) [

20] provides a historical example that highlights how colleagues at American host institutions in the 1970s were skeptical of Soviet visiting scholars, yet developed strong research collaborations throughout their grant periods. Robbins (2013) [

21] highlights how the visiting scholar program has fostered long-term research collaborations between US and Vietnamese visiting scholars in areas of sciences and international studies.

3.2. Fulbright Visiting Scholars Experience Unexpected Administrative Burdens

The articles included in this study often described Fulbright visiting scholars’ attitudes toward the US in relation to the specific geopolitical relationship that their home country had with the United States. Among the 14 studies presented in this review, 11 of them (78.6%) discussed the specific geopolitical relationship between the US and the home countries of the visiting scholars in relation to the scholars’ experience in the United States. These relationships may include US foreign policies and trade agreements, current or historical conflicts between the two nations, or even the specific binational Fulbright agreement between the US and the home country. Studies often described how scholars’ plans shifted due to pauses in the Fulbright Program in their home country depending on shifts in US foreign policies.

These shifts often manifested in unexpected administrative or bureaucratic burdens for visiting scholars. Participants in the studies represented in this review often expressed difficulty with the process of applying to and enrolling in the Fulbright visiting scholar program, citing bureaucratic problems from both the US government and their home government. For example, Chinese visiting scholars described a “burdensome” pre-departure formality that required them to deposit a large sum of money into a Chinese bank account that would be returned upon the end of their grant term [

17] (p. 16). As a government-sponsored education exchange program, the uniqueness of these scholars’ experiences may be that they are subject to the administrative burdens of both their academic institutions and of two national governments.

Irish visiting scholars to the US noted unexpected expectations at the institutional level for classroom management that were difficult to prepare for in advance without support from the Fulbright Program [

16]. Scholars in these studies relied on faculty at their US institutions and support from the international student service offices at their universities to navigate these challenges [

17,

19,

22]. This observation supports the argument that transnational partnerships in higher education should “establish centralized administrative infrastructure and appropriate human resources” [

18] (p. 136), perhaps to a further extent when considering government-funded exchange.

Although the administrative burden that visiting scholars experience is shared among the participants of these studies regardless of national origin, the following section explores the ways that these burdens may be specific to visiting scholars based on the relationship between the US and their home country and the binational agreement of the Fulbright program in question.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examined 14 selected publications from the last decade regarding Fulbright visiting scholars’ experiences in the United States. The purpose of the study is to identify the common experiences that Fulbright visiting scholars to the United States share according to qualitative and historical representations in peer-reviewed literature. After conducting a thematic analysis on the content of the empirical sources, it was found that the articles tended to examine the scholars’ attitudes toward the United States, the influence of the program on their academic and professional lives, and the specific relationships between their home countries and the United States.

The first theme, “Participating in the Fulbright Program complicates visiting scholars’ attitudes and opinions toward the United States,” highlighted their shared experience. Visiting scholars understood the professional benefits that their participation in the Fulbright Program would provide them, and they made lasting connections with American colleagues and community members. However, note that the articles in the study described the differences in scholar experiences based on their nations of origin. The visiting scholars maintained their critical viewpoints toward the United States, the specifics of which varied based on their home country.

Given the discussion in the literature that Fulbright scholars’ experiences are unique to the geopolitical relationship between the United States and the scholar’s home country, future qualitative research may add to the current body of literature, particularly from regions of the world underrepresented in the literature, such as Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America. Developing this area of research will provide a more complete understanding of how educational diplomacy functions in international higher education. Furthermore, these types of studies will bring attention to how foreign policy and international politics manifest themselves into higher education institutions, both in the US and around the world. The Fulbright Program offers one such lens to do so.

The articles included in this study represented few areas of the world, despite the Fulbright Program hosting exchanges with 160 countries worldwide [

1]. There were also only 14 studies included in the review, which illustrates how little empirical research there is on a program that has a significant reach in higher education in the United States and around the world. The Fulbright Program involves not only students around the world, but also scholars. More empirical research should be conducted to better understand Fulbright visiting scholars’ experiences.

One practical response to the result that Fulbright scholars experience administrative burden during their time in the Fulbright Program for administrators of the program, is to minimize administrative differences between binational commissions. Each binational commission is developed on the basis of the particular relationship that is established between the US and the partner country, given the geopolitical situation at that time [

4]. However, challenges such as the ones described by Fu [

18], in which Chinese visiting scholars were required to deposit personal funds into a bank account before participating in the program, or by Cheddadi [

15] who described Algerian bureaucratic procedures that take months to complete after being required to return to their home country based on the requirements of the Fulbright program. Although the Fulbright Program is a foreign policy strategy, the program directly impacts the experiences of visiting scholars in universities in the United States. Standardizing administrative differences could be a strategy that improves the experiences of these scholars.