The Interaction of War Impacts on Education: Experiences of School Teachers and Leaders

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Key Factors for the Conflict’s Continuity, and the Education Status in Yemen

1.2. War Impact on Education and the Initiatives for Repairing War-Torn Education Systems

2. Research Design

3. Findings

3.1. Impact of Conflict on Child Learners

3.1.1. From Displacement to Discrimination

Unfortunately, there is a lack of awareness among the people in general, and the awareness of some workers in these camps. There is a discrimination against the marginalized children. They call these children with racist descriptions, and they are also subjected to beatings and insults.

The war directly affected the escalation of violence on the marginalized group (Muhammashin)… When they fled the war to some camps outside the city of Aden, they became threatened, and their children could not get out of their camps because they were described as spies. This increases pressure on this group, and makes teaching their children more difficult.

In one of the Sana’a University offices, I found three young sisters who work as cleaners at the university. The eldest one is in the first grade of secondary school. Through my conversation with them, I discovered that they were studying when their father was with them before the war. When the war began, the father disappeared because he was in the military, and now, no one knows anything about him… During my conversations with the girls, they showed the extent of their dissatisfaction with the people dealing with them as cleaners, as when they were with their father, they had a comfortable life. Of course, this affected me a lot, and I felt sad about these children and the rest of the Yemeni children.

3.1.2. From Child Soldiers to Feeding the Conflict of Identities

The lack of awareness among school learners and children greatly contributes to exploiting and influencing them with illusions of victory or martyrdom, and that manhood is to carry weapons. The warring parties fuel sectarian feelings in them for fighting. This deprives them of their basic rights (e.g., the right to live, the right to education, and the right to live a decent life). We see the school learners who are affected by this propaganda wearing the military uniform and carrying weapons instead of wearing the school uniforms and carrying pens. This raises concerns about the future of coexistence between generations because of this conflict at the cultural and the national level.

The danger is also from children who are ideologically involved in the war. It is difficult for us to rehabilitate them afterwards, while it can be done with children who go to war to get money.

We are seeing what is circulated about the attempts of the Houthi-ruled party in the north to make deep changes in the curricula. The Houthis are working to change their culture by presenting a narrative based on religious mobilization, and the introduction of sectarian concepts that will negatively affect the future. We are very worried about our future, and we do not know what will happen in the light of this struggle that uses religious mobilization to gain political interests.

3.1.3. Societal Rejection and the Destruction of Mental Health

There is a large group of children suffering from psychological problems and behavioral disorders, especially those who live in the bombed areas. Our neighbor used to live in one of the conflict zones, but he along with his children was displaced to our neighborhood. Two of his children could not go to school because of fear and anxiety, and there are no psychiatrists to deal with these cases. And even if psychiatrists exist, not many people will go to them because of fear of social stigma.

3.2. Exploiting Education for Profit and the Normalization of Negativity

The war has contributed to creating an environment capable of transforming education into a negative investment, so private schools increased significantly. Compared to the absence of salaries in the state schools, teachers go to the private schools in search of what would meet their material needs. The matter was negatively reflected on the education process itself and on the economic side as well. There is no mentorship on schools’ work or their content. They only care about money.

Almost in every area, urban and rural, some phenomena that we did not know have appeared. Some people try to impose their views on others by force, and injustice prevails over justice. Children are brought up under conditions that present crime as the norm while the right has become an exception.

3.3. Cutting the Salary and Destroying the Teachers’ Dignity

The war destroyed everything in our lives... The teachers see directly what they did not imagine would happen one day... Whoever imagines that the teachers will work without a financial or moral return; financially to help them support those under their responsibility (a wife and children), and morally as they receive no appreciation or thanks. Some teachers continue to teach for fear of losing their job, and some others see that it is their duty toward the future of their learners. However, teaching will not be professionally conducted since teachers’ thinking is occupied, and their psyche is broken.

The old folk Yemeni proverb says: “Throat-cutting is better than salary-cutting.” Within three years, I find our schools almost empty of the teachers and the learners due to the interruption of salaries, which represents the lifeline of the teachers. There are many tragic human situations we live in and see with our eyes [that many people] suffering from incurable diseases, and unable to buy medicine until they die simply because modesty and self-dignity prevented them from seeking help. There is a teacher in one of the… schools who fell on the ground in the school queue between the feet of his learners. He had been exhausted by cancer that has spread in his body six months ago and died without his colleagues’ knowledge of his suffering. There is nothing to say but “there is neither power nor might except with/by God”.

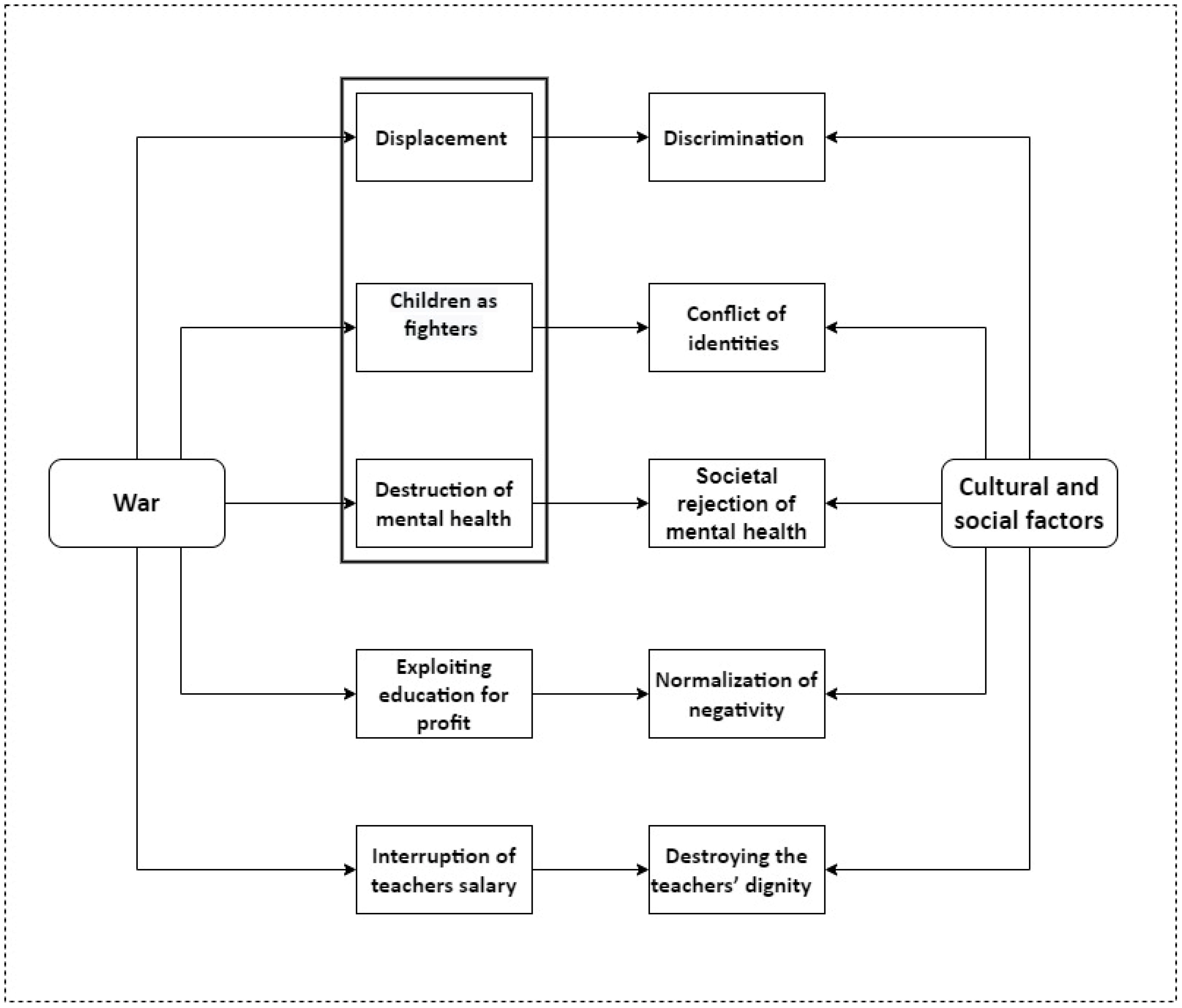

3.4. A Model of the Interaction of War’s Impacts on Education

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Forcing thousands of families to flee to safer areas.

- Separating families in quest for income.

- Forcing children to drop out of schools and/or receiving low quality education.

- Overcrowding classrooms with the displaced in safer areas, affecting their learning.

- Dispersing peers, making the adaptation of the displaced students more difficult.

- Affecting children’s psychology and their academic achievement.

- Recruiting many children for military purposes, putting children’s lives at risk.

- Spreading malnutrition, diseases among the displaced, affecting their capacities.

- Keeping female children at home and sending only males to schools.

- Increasing child labor due to families’ financial challenges.

- Destroying schools and/or using them for military purposes.

- Killing, injuring, or assaulting students, teachers, and educators.

- Declining the education quality.

- Depriving employees of their salaries.

References

- O’Malley, B. Education under Attack, 2010: A Global Study on Targeted Political and Military Violence against Education Staff, Students, Teachers, Union and Government Officials, Aid Workers and Institutions; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.Q. Study of the impact of socio-political conflicts on Libyan children and their education system. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Transl. Stud. 2021, 9, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dar, A.A.; Deb, S. Mental Health in the Face of Armed Conflict: Experience from Young Adults of Kashmir. J. Loss Trauma Int. Perspect. Stress Coping 2020, 26, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifian, M.S.; Kennedy, P. Teachers in war zone education: Literature review and implications. Int. J. Whole Child 2019, 4, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Poirier, T. The effects of armed conflict on schooling in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2012, 32, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- UNICEF. Syria Education Sector Analysis: The Effects of the Crisis on Education in Areas Controlled by the Government of Syria, 2010–2015; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bazzaz, S.M.J. The Social and Psychological Effects of the Iraqi-American War on Children in Iraqi Society. Unpublished. Master Thesis, College of Arts, Baghdad University, Baghdad, Iraq, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rahima, N.S. The impact of armed conflicts on the education quality in Iraq. J. Cent. Arab. Int. Stud. Al-Mustansiriya Univ. 2017, 14, 220–255. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Periodic Statistics; Ministry of Education: Sana’a, Yemen, 2016.

- Studies and Educational Media Center. Outside the School Walls: Implications of the War and Its Implications for Education in Yemen; Studies and Educational Media Center: Sana’a, Yemen, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Education in Yemen: Five Years of Withstanding Aggression; Ministry of Education: Sana’a, Yemen, 2020.

- Dunlop, E.; King, E. Education at the intersection of conflict and peace: The inclusion and framing of education provisions in African peace agreements from 1975–2017. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2019, 51, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.D.; Saltarelli, D. The Two Faces of Education in Ethnic Conflict: Towards a Peacebuilding Education for Children; UNICEF Innocent Research Centre: Florence, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, A. Foreign and Domestic Influences in the War in Yemen. In The Proxy Wars Project; PWP Conflict Studies; Virginia Tech Publishing: Blacksburg, VA, USA.

- Hasanović, M. Psychological consequences of war-traumatized children and adolescents in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Acta Medica Acad. 2011, 40, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Han, Q.; Zuo, J.; Rameezdeen, R. Perceived discrimination of displaced people in development-induced displacement and resettlement: The role of integration. Cities 2020, 101, 102692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahfali, M. Anti-Black Racism in Yemen: Manifestations and Responses. Arab Reform Initiative. 2021. Available online: https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/anti-black-racism-in-yemen (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Muthanna, A. Exploring the Beliefs of Teacher Educators, Students, and Administrators: A Case Study of the English Language Teacher Education Program in Yemen. Master’s Thesis, METU: Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Yemen: Country Report on Out-of-School Children; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Muthanna, A.; Sang, G. Brain drain in higher education: Critical voices on teacher education in Yemen. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2018, 16, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiichi, O. Achieving education for all in Yemen: Assessment and current status. J. Int. Coop. Stud. 2004, 12, 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ghundol, B.; Muthanna, A. Conflict and international education: Experiences of Yemeni international students. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2022, 52, 933–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthanna, A.; Sang, G. State of University Library: Challenges and Solutions for Yemen. J. Acad. Libr. 2019, 45, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Education Disrupted: Impact of the Conflict on Children’s Education in Yemen; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mwatana. War of Ignorance: Field Study on the Impact of the Armed Conflict on Access to Education in Yemen. 2021. Available online: https://mwatana.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Executive-summary-of-education-study-FINAL-Jan-28-21-1.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Moyi, P. Who goes to school? School enrollment patterns in Somalia. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2012, 32, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Word Bank. Somalia Economic Update: Building Education to Boost Human Capital, 4th ed.; Word Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bekalo, S.A.; Brophy, M.; Welford, A.G. The development of education in post-conflict ‘Somaliland’. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2003, 23, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, S.M. Building peace through education in a post-conflict environment: A case study exploring perceptions of best practices. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2016, 51, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blattman, C.; Fiala, N.; Martinez, S. Generating Skilled Self-Employment in Developing Countries: Experimental Evidence from Uganda. Q. J. Econ. 2013, 129, 697–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transfeld, M.; Heinze, M.C. Understanding Peace Requirements in Yemen; Carpo: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, C. Yemen and education: Shaping bottom-up emergent responses around tribal values and customary law. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 2018, 20, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, T.G. Education to transform the world: Limits and possibilities in and against the SDGs and ESD. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2020, 30, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, S. Culturally responsive peacebuilding pedagogy: A case study of Fambul Tok Peace Clubs in conflict-affected Sierre Leone. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2019, 28, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranovicé, B. History Textbooks in Post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina. Intercult. Educ. 2001, 12, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommering, E.V. Formal history education in Lebanon: Crossroads of past conflicts and prospects for peace. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2015, 41, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Clandinin, D.J.; Huber, J. Narrative inquiry. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 3rd ed.; Peterson, P., Baker, E., McGaw, B., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 436–441. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Introduction: Critical methodologies and indigenous inquiry. In Critical and Indigenous Methodologies; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. Introducing Research Methodology; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. The Power of Constructivist Grounded Theory for Critical Inquiry. Qual. Inq. 2016, 23, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coning, C. Understanding peacebuilding: Consolidating the peace process. Confl. Trends 2008, 4, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Milton, S.; Barakat, S. Higher education as the catalyst of recovery in conflict-affected societies. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2016, 14, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Conflict Sensitivity and Peacebuilding: Programming Guide; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, A. The need for contextualisation in the analysis of curriculum content in conflict. In Education and Conflict Review: Theories and Conceptual Frameworks in Education, Conflict and Peacebuilding; Pherali, T., Magee, A., Eds.; Centre for Education and International Development (CEID): London, UK, 2019; pp. 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Menier, C.; Forget, R.; Lambert, J. Evaluation of two-point discrimination in children: Reliability, effects of passive displacement and voluntary movement. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1996, 38, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, L.; Roberts, L.; Wheaton, W.; Acham, A.; Boothby, N.; Ager, A. Measuring violence against women amidst war and displacement in northern Uganda using the “neighbourhood method”. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 64, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pseudonym | Age | Gender | Degree | Specialty | Work | Province | Teaching and Leadership Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saber | 43 | Male | BA | Geography | Leader | Marib | 15 |

| Hadeel | 27 | Female | BA | English | Teacher | Hadhramaut | 4 |

| Sadeq | 55 | Male | MA | Educational management | Teacher | Ibb | 25 |

| Shugoon | 33 | Female | BA | Social work | Leader | Taiz | 8 |

| Rawan | 45 | Female | BA | Mathematics | Leader | Abyan | 15 |

| Husain | 42 | Male | MA | Arabic | Teacher | Thamar | 14 |

| Salman | 30 | Male | BA | English | Teacher | Amran | 8 |

| Amran | 37 | Male | BA | Islamic education | Teacher | Sanaa | 12 |

| Zaher | 58 | Male | BA | Science | Teacher | Lahj | 29 |

| Nasma | 44 | Female | BA | Social work | Leader | Aden | 15 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muthanna, A.; Almahfali, M.; Haider, A. The Interaction of War Impacts on Education: Experiences of School Teachers and Leaders. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100719

Muthanna A, Almahfali M, Haider A. The Interaction of War Impacts on Education: Experiences of School Teachers and Leaders. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(10):719. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100719

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuthanna, Abdulghani, Mohammed Almahfali, and Abdullateef Haider. 2022. "The Interaction of War Impacts on Education: Experiences of School Teachers and Leaders" Education Sciences 12, no. 10: 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100719

APA StyleMuthanna, A., Almahfali, M., & Haider, A. (2022). The Interaction of War Impacts on Education: Experiences of School Teachers and Leaders. Education Sciences, 12(10), 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100719