Conceptual Model of Differentiated-Instruction (DI) Based on Teachers’ Experiences in Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. The Study Context

2.4. Study Instruments: Unstructured Interview Guide

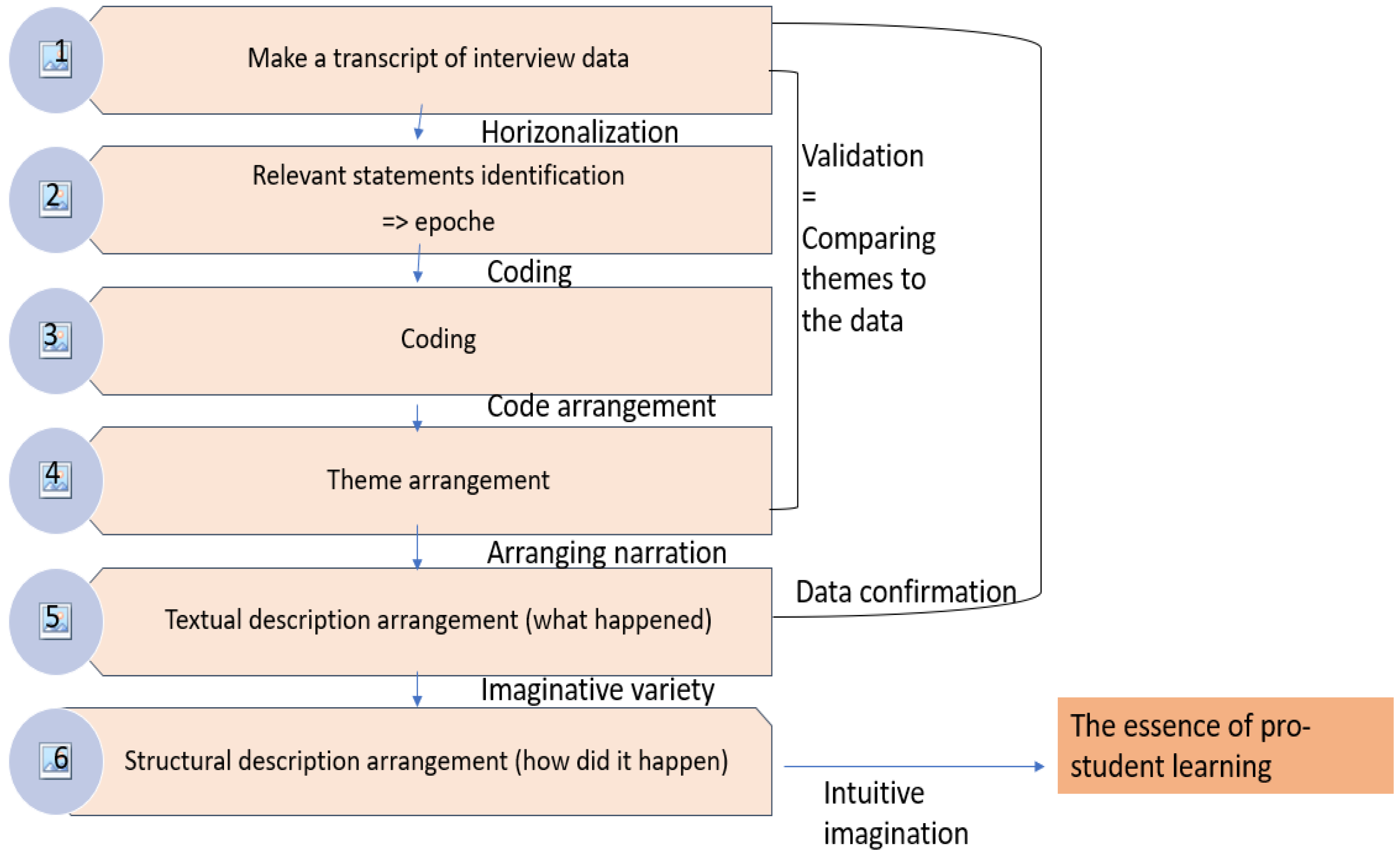

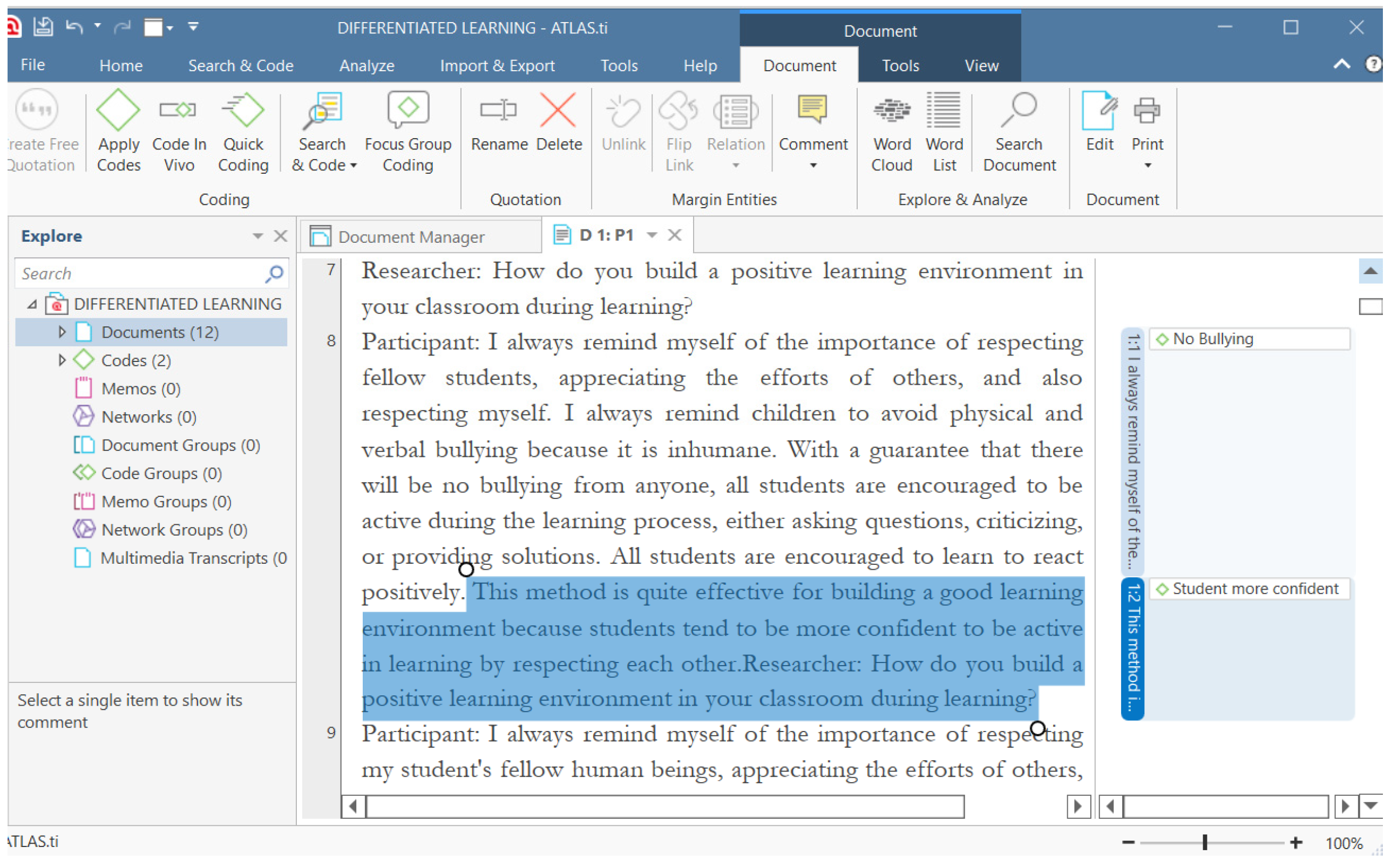

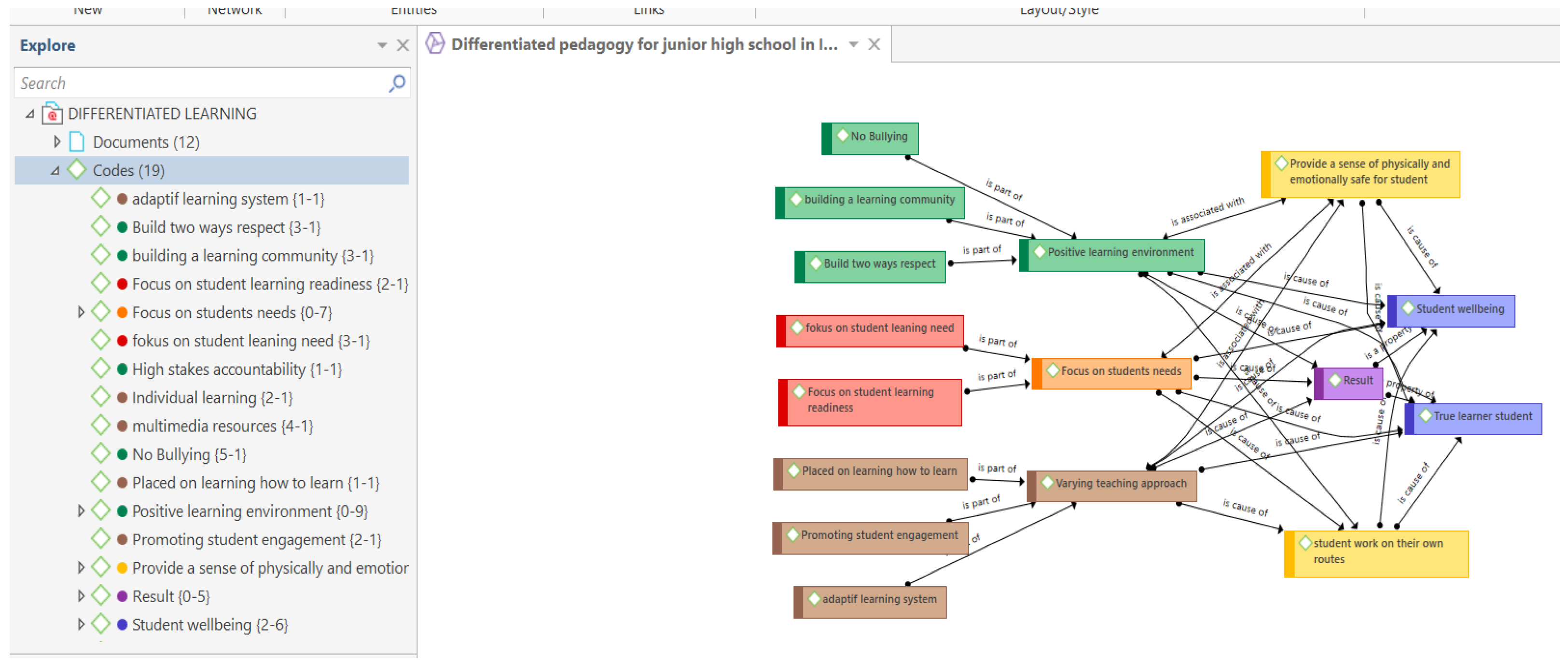

2.5. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis

2.5.1. Coding Process

2.5.2. Research Result Formation

2.5.3. Textual Description Arrangement Formation (Textual Narrative)

2.5.4. Structural Description Formation

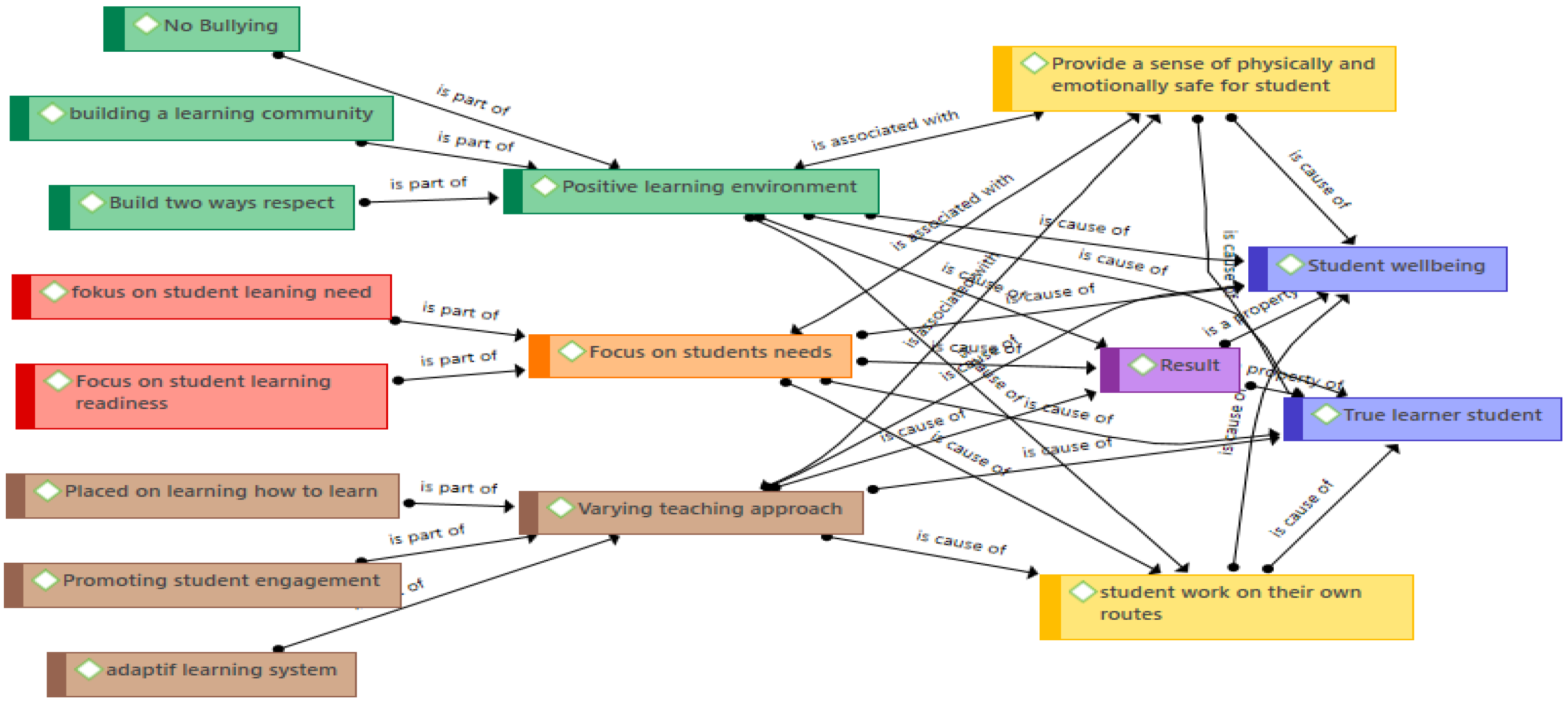

3. Results

3.1. Developing a Positive Learning Environment

3.1.1. No Bullying

In my experience, students will be more cheerful and enthusiastic about learning when they get good treatment from the teacher and fellow students in class. This is a challenge for us as teachers to be able to build a sense of security and comfort physically and mentally so that students can learn well; the most obvious way is to ensure that there is no bullying in schools.(P1, lines 5–7)

During the learning process, as a teacher, I always [emphasize] the importance of respecting fellow human beings, respecting one’s efforts, and respecting yourself by avoiding bullying, physically and verbally. At the beginning of learning, children are always accustomed to making class agreements so that learning runs accordingly. One of the agreement’s contents is not to bully anyone. With the guarantee that there will be no bullying from anyone, students feel more confident to be active in class during the learning process, either asking questions, criticizing, or even providing solutions. Students are also always directed to have a positive reaction to others; thus, the learning environment becomes a positive environment for children’s development even though they have various conditions and different learning readiness(P2, lines 11–23).

At the beginning of every lesson, apart from praying, I always start learning with mutual agreement about class rules, learning procedures, and attitudes that need to be developed during the learning process. This method is quite effective in creating a conducive learning environment, especially in building mutual respect, self-confidence, discipline awareness, and anti-bullying. Based on my experience so far, making mutual agreements before learning is very effective in controlling student behavior and building a conducive classroom atmosphere without forcing the teacher’s will(P9, lines 6–10).

Bullying is a major problem that often causes mental problems and a loss of confidence in its victims. So that all children have confidence in class and dare to express their thoughts without being ashamed or afraid of anyone, I always remind them to keep away from verbal and physical bullying toward anyone(P12, lines 7–11).

3.1.2. Building a Two-Way Respect

To build mutual respect between friends, I have a program called ‘My Day’ during distance learning. This program is one of the strategies that I do to raise the awareness of each child that everyone has a different life, so everyone must respect each other. The strategy I use to get students used to respecting other people is that in every first 10 min of class, I ask the children to take turns telling stories about themselves and their experiences. Other friends listen well, then they give a response via emoticons on the zoom layer or respond to it positively. Every time we meet, at least one child tells a story(P1, lines 15–26).

In implementing differentiated learning, I make an effort to grow students’ respect for fellow human beings. Respect comes from the heart because there is empathy for others. So, in learning, I often do role-playing practices to foster empathy and respect among students. Indeed, it is not an easy thing and cannot be done once and immediately succeed. It takes patience to do it(P5, lines 11–16).

3.1.3. Building a Learning Community

For the past two years, during the COVID-19 period, I have always tried to have a group learning process, even if only through Zoom meetings or video calls. I ask the children to hold regular meetings between group members to do the tasks together. According to the reports that the children gave, during independent group work, the students carried out peer mentoring and peered lessons. Students who are good at guiding students who have not succeeded in mastering the teaching material. These activities help children learn more easily, eliminate the feeling of loneliness, and make it easier for me as a teacher because the peer guidance process in each study group makes learning easier for students to understand(P6, lines 17–25).

Even though during the COVID-19 pandemic, learning was carried out online, I still encouraged children to form learning communities, whether with classmates or with friends from different classes. For grade 9, they have also succeeded in forming a learning community with fellow grade 9 students from other schools. I do it by working with fellow teachers in other schools to connect students to get to know each other and then form inter-school social studies learning community. From the responses and reflections made by the children, they are happy to join this learning community program(P11, lines 15–22)

3.2. Varying Teaching Methods

3.2.1. Promoting Student Engagement

Schools were closed during the COVID-19 period, and learning was carried out from home online. So that the children do not feel alone, I always set learning in the form of project-based group work. Since the first meeting, I have given the project learning steps every week. In the student worksheets, I set them so that individually, they report what was done in their group. So even though they work as a group, they individually have their own responsibilities.

Oh… yes, in the context of classroom learning, I realize that students will absorb teaching materials more quickly if they are actively involved in learning, starting from concept building or in the form of applications. Well, based on my experience in teaching, the things that students like are when at the beginning of the lesson, the teacher explains in advance what is being assessed, how the learning steps are carried out, and the work is done in groups(P8, lines 45–49).

3.2.2. Placed on Learning How to Learn

I often show children various motivational videos, especially videos that can provide understanding and awareness of how our minds learn new concepts biologically and demonstrate strategies for effective learning(P6, lines 67–69).

3.2.3. Adaptive Learning System

In a condition like this, yes, ma’am, I have difficulty controlling whether the students have mastered the learning competencies. So to overcome this, I tried to adopt various free learning apps. These apps are handy and flexible. I can control students whenever they come to class, work, and do what they do individually(P10, lines 71–74).

To provide educational services that follow the potential of each student, I try to implement a different instructional system for each student according to the readiness of each student to learn. This is still an experimental process, ma’am... I use the diagnostic assessment results to develop a range of instructional instruction suitable for individual students. I did this process with the help of a simple application that I created based on excel. In the future, I plan to develop this adaptive learning system more professionally so that learning is more effective and efficient(P9, lines 67–75).

3.3. Learning Outcomes That Focus on Individual Students

3.3.1. True Learner Student

The ideal learning outcomes are outcomes that are beneficial to the lives of students and others. So, when teaching, I always try to instill the attitude of a true learner. I often tell children that the best way to become a true learner is to learn to listen to other people talk even though you know it already. From what we hear from other people, at least we can learn something new or something different from before. Even when you listen to other people’s wrong statements, you will know how so you don’t make the same mistake in understanding something(P3, lines 58–63).

A statement made by P7 supports P3’s statement:

I believe that students need the ability to become true learners, not only as long as they are students but also to equip them for life. They need to be educated with adaptive skills and abilities. A true learner is someone who can see learning opportunities and then differentiate effectively to focus only on those that will add value to their knowledge and development, as is needed today(P7, lines 56–60).

3.3.2. Student Well-Being

Whenever I teach, I often ask the children what they need, what they want to do, and how they feel. Students tend to be more open when we listen to them well and provide feedback on what they have to say. Children give a signal that when wishes come true, they can feel proud and happy. Well… a teacher’s job is to nurture children to have positive expectations so that student well-being becomes genuine well-being, not a momentary pleasure(P4, lines 89–94).

4. Discussions

4.1. Teachers Provide a Sense of Physically and Emotionally Safe for Student

4.2. Students Work on Their Respective Routes

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fitrah, H.; Suyanto, S.; Sugiharsono, S.; Hasanah, E. Developing a School Culture through Malamang Culture in Indonesia. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 6667–6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanah, E.; Zamroni, Z.; Dardiri, A.; Supardi, S. Indonesian Adolescents Experience of Parenting Processes that Positively Impacted Youth Identity. Qual. Rep. 2019, 24, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanifah, N.; Mustapa, A. Seeking Intersection of Religions: An Alternative Solution to Prevent the Problem of Religious Intolerance in Indonesia. Walisongo J. Penelit. Sos. Keagamaan 2016, 24, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enung; Hasanah; Al, M.I.; Badar; Ghazy, M.I. Factors That Drive the Choice of Schools for Children in Middle-Class Muslim Families in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study. Qual. Rep. 2022, 27, 1393–1409. [Google Scholar]

- Benner, A.D.; Boyle, A.E.; Sadler, S. Parental Involvement and Adolescents’ Educational Success: The Roles of Prior Achievement and Socioeconomic Status. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusnaini, R.; Raharjo, R.; Suryaningsih, A.; Noventari, W. Intensifikasi Profil Pelajar Pancasila dan Implikasinya Terhadap Ketahanan Pribadi Siswa. J. Ketahanan Nas. 2021, 27, 230–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurjanah, S. Internalisasi Nilai-Nilai Pancasila Pada Pelajar (Upaya Mencegah Aliran Anti Pancasila di Kalangan Pelajar). J. Stud. Agama 2017, 5, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kusdarini, E.; Sunarso, S.; Arpannudin, I. The implementation of pancasila education through field work learning model. J. Cakrawala Pendidik. 2020, 39, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemendikbud Program sekolah penggerak. Kementeri. Pendidik. dan Kebud. Ris. dan Teknol. 2021, 1, 1–23.

- Robledo-Ardila, C.; Roman-Calderon, J.P. Individual potential and its relationship with past and future performance. J. Educ. Bus. 2019, 95, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezer, M. Analysing secondary school students’ social justice beliefs through ethical dilemma scenarios. Ted Eğitim Ve Bilim 2020, 45, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Harding, S.R.; Diaz, E.; Schamberger, A.; Carollo, O. Psychological sense of community and university mission as predictors of student social justice engagement. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 2015, 19, 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2016: A Fair Chance for Every Child; Publ. Home Page; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Adami, R.; Dineen, K. Discourses of childism: How covid-19 has unveiled prejudice, discrimination and social injustice against children in the everyday. Int. J. Child. Rights 2021, 29, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriere, J.S.; Pimentel, S.D.; Yakobov, E.; Edwards, R.R. A systematic review of the association between perceived injustice and pain-related outcomes in individuals with musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med. 2020, 21, 1449–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudeau, S.; Croizet, J.C. Hidden advantages and disadvantages of social class: How classroom settings reproduce social inequality by staging unfair comparison. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patphol, M. The 3es model: A coaching model for enhancing secondary student potential in thailand. Int. J. Pedagog. Curric. 2021, 28, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovagnati, V.; Pitt, E.; Winstone, N. Feedback cultures, histories and literacies: International postgraduate students’ experiences. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2021, 47, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, J.A. The “new normal” in education. Prospects 2020, 51, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.; Charteris, J.; Anderson, J.; Boyle, C. Fostering school connectedness online for students with diverse learning needs: Inclusive education in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2021, 36, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, A.M. Digital media production to support literacy for secondary students with diverse learning abilities. J. Media Lit. Educ. 2017, 9, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wong, L.P.W. Career and life planning education: Extending the self-concept theory and its multidimensional model to assess career-related self-concept of students with diverse abilities. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2020, 3, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruthers, C.B.; Hedman, E.L.; Matyas, M.L. Undergraduate research programs build skills for diverse students. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2021, 45, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, J.K. The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Race. Philos. Rev. 2019, 128, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, I.; Utama, B. Kesenjangan kualitas layanan pendidikan di indonesia pada masa darurat covid-19: Telaah demografi atas implementasi kebijakan belajar dari rumah. J. Kependud. Indones. 2020, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Záhorec, J.; Nagyová, A.; Hašková, A. Teachers’ Attitudes to Incorporation Digital Means in Teaching Process in Relation to the Subjects they Teach. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. 2019, 9, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satria, R.; Adiprima, P.; Wulan, K.S.; Harjatanaya, T.Y. Panduan Pengembangan Projek Penguatan Profil Pelajar Pancasila [Guide to the Development of Pancasila Student Profile Strengthening Projects]. Jakarta, Badan Standar, Kurikulum, dan Asesmen Pendidikan. 2022, pp. 1–137. Available online: https://kurikulum.kemdikbud.go.id/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Panduan-Penguatan-Projek-Profil-Pancasila.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Ruhimat, T.; Darmawan, D. Development of Group-Based Differentiated Learning (GBDL) Models. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 2020, 5, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.; Suhana, S.; Zakiah, Q.Y. Analisis kebijakan penguatan pendidikan karakater dalam mewujudkan pelajar pancasila. J. Manaj. Pendidik. Ilmu Sosisl 2021, 2, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Waterworth, P. Creating Joyful Learning within a Democratic Classroom. J. Teach. Learn. Elem. Educ. 2020, 3, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.S. Formative Learning Experiences of Urban Mathematics Teachers’ and Their Role in Classroom Care Practices and Student Belonging. Urban Educ. 2019, 55, 507–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondi, C.F.; Giovanelli, A.; Reynolds, A.J. Fostering socio-emotional learning through early childhood intervention. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 2021, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestu, D.A.; Rochmat, S. Filosofi merdeka belajar berdasarkan perspektif pendiri bangsa. J. Pendidik. dan Kebud. 2021, 6, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S.M.; McCoach, D.B.; Little, C.A.; Muller, L.M.; Kaniskan, R.B. The effects of differentiated instruction and enrichment pedagogy on reading achievement in five elementary schools. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2011, 48, 462–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugas, D. Group Dynamics and Individual Roles: A Differentiated Approach to Social-Emotional Learning. Clear. House A J. Educ. Strat. Issues Ideas 2016, 90, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozas, M.; Letzel, V.; Lindner, K.-T.; Schwab, S. DI (Differentiated Instruction) Does Matter! The Effects of DI on Secondary School Students’ Well-Being, Social Inclusion and Academic Self-Concept. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 729027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Choi, H. Rethinking the flipped learning pre-class: Its influence on the success of flipped learning and related factors. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 50, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudiawan, A.; Sunarso, B.; Suharmoko, S.; Sari, F.; Ahmadi, A. Successful online learning factors in COVID-19 era: Study of Islamic higher education in West Papua, Indonesia. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2021, 10, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, E. Factors influence the success of e-learning systems for distance learning at the University. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Information Management and Technology (ICIMTech), Bandung, Indonesia, 13–14 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nurlaila, N. Faktor-Faktor Keberhasilan Pembelajaran Bahasa: Perspektif Intake Factors. J. Kependidikan J. Has. Penelit. Dan Kaji. Kepustakaan Di Bid. Pendidik. Pengajaran Dan Pembelajaran 2020, 6, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, X. Influence of affective factors on learning ability in second language acquisition. Rev. Argent. Clin. Psicol. 2020, 29, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanah, E.; Desstya, A.; Kusumawati, I.; Limba, A.; Kusdianto, K. The mediating role of student independence on graduate quality in distributed learning. Int. J. Instr. 2022, 15, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, E.N.; Zamroni, Z. The impact of independent learning on students’ accounting learning outcomes at vocational high school. J. Pendidik. Vokasi 2019, 9, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome, L. Interpreting Children’s Rights Education: Three perspectives and three roles for teachers. Citizenship Soc. Econ. Educ. 2016, 15, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapa, A.N. Differentiated Learning Model For Student with Reading Difficulties. J. Teknol. Pendidik. 2020, 22, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jager, T. Guidelines to assist the implementation of differentiated learning activities in South African secondary schools. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2013, 17, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, M.C. Leading Differentiated Learning for the Gifted. Roeper Rev. 2019, 41, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.I.H.; Aziz, A.A. TS25 school teachers’ perceptions of differentiated learning in diverse ESL classrooms. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2019, 13, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hertberg-Davis, H. Myth 7: Differentiation in the Regular Classroom Is Equivalent to Gifted Programs and Is Sufficient. Gift. Child Q. 2009, 53, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.; Puustinen, M. Rethinking society and knowledge in Finnish social studies textbooks. J. Curric. Stud. 2021, 53, 857–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghroucheni, Y.Z.; Al Achhab, M.; El Mohajir, B.E. A Bayesian Network Based on the Differentiated Pedagogy to Generate Learning Object According to FSLSM. Int. J. Recent Contrib. Eng. Sci. IT (iJES) 2015, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Suwartiningsih, S. Penerapan Pembelajaran Berdiferensiasi untuk Meningkatkan Hasil Belajar Siswa pada Mata Pelajaran IPA Pokok Bahasan Tanah dan Keberlangsungan Kehidupan di Kelas IXb Semester Genap SMPN 4 Monta Tahun Pelajaran 2020/2021. J. Pendidik. Pembelajaran Indones. 2021, 1, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, B.E.; Witkop, C.T.; Varpio, L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2019, 8, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath Heath Williams, Sun Yat-sen University, Zhuhai The Meaning of “Phenomenology”: Qualitative and Philosophical Phenomenological Research Methods. Qual. Rep. 2021, 26, 366–385. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Greenwood, M.; Prior, S.; Shearer, T.; Walkem, K.; Young, S.; Bywaters, D.; Walker, K. Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, C. The Inconvenient Truth About Convenience and Purposive Samples. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 43, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assembly, W. WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. In Proceedings of the 48th General Assembly, Somerset West, South Africa, 22–26 October 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vaida, L.; Todor, B.I.; Lile, I.E.; Mut, A.-M.; Mihaiu, A.; Todor, L. Contention following the orthodontic treatment and prevalence of relapse. Hum. Vet. Med. 2019, 11, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hardavella, G.; Gagnat, A.A.; Xhamalaj, D.; Saad, N. How to prepare for an interview. Breathe 2016, 12, e86–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Engward, H.; Goldspink, S. Lodgers in the house: Living with the data in interpretive phenomenological analysis research. Reflect. Pract. 2020, 21, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, T.M.; Pope, E.M.; Woolf, N.; Silver, C. It will be very helpful once I understand ATLAS.ti”: Teaching ATLAS.ti using the Five-Level QDA method. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2018, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishaw, A.; Tadesse, T.; Campbell, C.; Gillies, R.M. Exploring the Unexpected Transition to Online Learning Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic in an Ethiopian-Public-University Context. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Shih, Y.-H. Development of John Dewey’s educational philosophy and its implications for children’s education. Policy Futur. Educ. 2021, 19, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, D.S.; Davis-Berman, J. Positive Psychology and Outdoor Education. J. Exp. Educ. 2005, 28, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.A. Why won’t it Stick? Positive Psychology and Positive Education. Psychol. Well-Being Theory, Res. Pract. 2016, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.L.; Graham, A.P. Improving student wellbeing: Having a say at school. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2015, 27, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babal, J.C.; Abraham, O.; Webber, S.; Watterson, T.; Moua, P.; Chen, J. Student Pharmacist Perspectives on Factors That Influence Wellbeing During Pharmacy School. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, ajpe7831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszynska, P. From calculation to deliberation: The contemporaneity of Dewey. Cult. Theory Crit. 2021, 62, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, M.; Samarawickrema, G. The criteria of effective teaching in a changing higher education context. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2010, 29, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, R.; Shrestha, M. Student Friendly Teaching and Learning Environment: Experiences from Technical Vocational Educational Training Schools in Nepal. Eur. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapfe, L.; Gross, C. How do characteristics of educational systems shape educational inequalities? Results from a systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 109, 101837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Li, K.; Yan, J. Understanding user trust in artificial intelligence-based educational systems: Evidence from China. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 1693–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, S.; Tsani, I.; Syazali, M.; Umam, R.; Jermsittiparsert, K. The management of educational system using three law Auguste Comte: A case of Islamic schools. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X. Response to “A design framework for enhancing engagement in student-centered learning: Own it, learn it, and share it”: A design perspective. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2021, 69, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achkovska-Leshkovska, E.; Spaseva, M. John Dewey’s educational theory and educational implications of Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligences theory. Int. J. Cogn. Res. Sci. Eng. Educ. 2016, 4, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, I.; Chiu, M.M.; Patrick, H. Connecting teacher and student motivation: Student-perceived teacher need-supportive practices and student need satisfaction. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 64, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saminathen, M.G.; Plenty, S.; Modin, B. The Role of Academic Achievement in the Relationship between School Ethos and Adolescent Distress and Aggression: A Study of Ninth Grade Students in the Segregated School Landscape of Stockholm. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 50, 1205–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loes, C.N.; Culver, K.C.; Trolian, T.L. How Collaborative Learning Enhances Students’ Openness to Diversity. J. High. Educ. 2018, 89, 935–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, A.; Kretschmann, J.; Gronostaj, A.; Vock, M. More enjoyment, less anxiety and boredom: How achievement emotions relate to academic self-concept and teachers’ diagnostic skills. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 62, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M. Curriculum Development and Accreditation Standards in the Traditional Islamic Schools in Indonesia. J. Curric. Stud. Res. 2020, 3, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, M.; Suryadi, E. Guru sebagai fasilitator dan efektivitas belajar siswa. J. Pendidik. Manaj. Perkantoran 2019, 4, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewantara, K.H. Karya Ki Hadjar Dewantara. In Kebudayaan; Majelis Luhur Persatuan Tamansiswa: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 1967; ISBN 9795187635. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, L.M.; Goforth, A.; Sacra, M.; Ahlers, K. Collaboration to Support Rural Student Social-Emotional Needs. Rural Educ. 2017, 38, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; Calabrò, T.; Iiritano, G.; Pellicanò, D.S.; Petrungaro, G.; Trecozzi, M.R. Green and Safety School Regional Program to Sustainable Development Using Limited Traffic Zone. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2021, 16, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yablon, Y.B. School safety and school connectedness as resilience factors for students facing terror. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 34, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N.; Mahadi, N. The significance of mutual recognition respect in mediating the relationships between trait emotional intelligence, affective commitment and job satisfaction. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 105, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heap, S.P.H. A community of advantage or mutual respect? Int. Rev. Econ. 2020, 68, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweke, W. Connecting asset building and community development. In Reengineering Community Development for the 21st Century; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Raufelder, D.; Kulakow, S. The role of social belonging and exclusion at school and the teacher–student relationship for the development of learned helplessness in adolescents. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 92, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardino, J.M.; Cruz, R.A.O.-D. Understanding of learning styles and teaching strategies towards improving the teaching and learning of mathematics. LUMAT Int. J. Math Sci. Technol. Educ. 2020, 8, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, J.; Hornstra, L.; Volman, M. The meaning of meaningful learning in mathematics in upper-primary education. Learn. Environ. Res. 2020, 24, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Fan, K.-K.; Xiao, P.-W. The Effects of Learning Styles and Meaningful Learning on the Learning Achievement of Gamification Health Education Curriculum. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2015, 11, 1211–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.L.; Graham, A.P.; Simmons, C.; Thomas, N.P. Positive links between student participation, recognition and wellbeing at school. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 111, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasanah, E.; Suyatno, S.; Maryani, I.; Badar, M.I.A.; Fitria, Y.; Patmasari, L. Conceptual Model of Differentiated-Instruction (DI) Based on Teachers’ Experiences in Indonesia. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100650

Hasanah E, Suyatno S, Maryani I, Badar MIA, Fitria Y, Patmasari L. Conceptual Model of Differentiated-Instruction (DI) Based on Teachers’ Experiences in Indonesia. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(10):650. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100650

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasanah, Enung, Suyatno Suyatno, Ika Maryani, M Ikhwan Al Badar, Yanti Fitria, and Linda Patmasari. 2022. "Conceptual Model of Differentiated-Instruction (DI) Based on Teachers’ Experiences in Indonesia" Education Sciences 12, no. 10: 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100650

APA StyleHasanah, E., Suyatno, S., Maryani, I., Badar, M. I. A., Fitria, Y., & Patmasari, L. (2022). Conceptual Model of Differentiated-Instruction (DI) Based on Teachers’ Experiences in Indonesia. Education Sciences, 12(10), 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100650