Abstract

The system for measuring the quality of education (SIMCE) is a standardised evaluation that provides results on the academic achievement of Chilean students, while also including indicators of personal and social development. Through a mixed analysis of variables extracted from these indicators, the purpose of this research study is to build a measurement system to assess the favourable and unfavourable emotions of students who took the test in 2018. To contextualise this work, a systematic literature review was carried out synthetising scientific evidence concerning emotions and the interactional context of the classroom. Through a methodological transposition, a qualitative theoretical model epistemologically grounded on radical constructivism was validated quantitatively. This transposition resulted in the construction of three indices of favourable and unfavourable emotions: motivation arising from interaction, exclusionary interaction and interactional context. The results show favourable and unfavourable emotions for learning are a variable in the SIMCE indicators that can be used to understand student academic achievement, confirming existing empirical evidence regarding the explanatory and predictive value of emotions in students’ performance. These results highlight the potential benefits of expanding on this type of research to improve the quality of Chilean education based on the resources already available in the current evaluation system.

1. Introduction

Understanding the participation of emotions in the different aspects of education is critical in the learning process from the radical constructivist perspective [1,2]. Within this framework, instruments assessing the explanatory value of emotions associated with the interactional context of the classroom are vital for understanding academic achievement in different measurement systems. In Chile, the measurement of the quality of the education system (SIMCE) is employing standardised tests at different levels to assess the learning outcomes of schools in relationship with the objectives and skills established in the current curriculum in different learning areas. Along with the standardised test, characterisation questionnaires that include personal and social development indicators are applied for students, teachers and parents.

On the one hand, this system does not consider the evaluation of students’ emotions as a relevant factor. A similar situation is observed in other standardised measurement systems in the world [3]. From the conceptualisation of emotions proposed by Humberto Maturana and adopted in this work, this result is particularly problematic, since emotions are understood as dynamic bodily dispositions that constitute the basis of our domains of action [1,2]. Therefore, this implies that there can be no actions that are not based on emotion.

There is concern regarding the possibilities for measuring emotions in the educational context using instruments that collect information through characterisation questionnaires. On the other hand, SIMCE does incorporate personal and social development indicators for contextualisation purposes. This includes specific indicators related to students’ self-esteem and motivation, citizens’ participation and training and healthy lifestyle habits. The instrument allows researchers to perform the characterisation of what happens inside educational establishments, providing information on how students perceive the interactional contexts that frame their learning experience. Thus, the interactions in the educational context would be based on various emotions that can enable the achievement of learning, measurable through standardised tests such as SIMCE. By referring to the dimensions of the interactional experience that contextualise student learning, it is possible to propose that the personal and social development indicators contained in the SIMCE questionnaires could provide information about the emotions that emerge in the students’ learning process.

This study aims to contribute to constructing a measurement system that allows us to assess favourable and unfavourable emotions for learning. To ground this work in the educational field, a systematic literature review was carried out in the Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) databases aimed to synthesise scientific evidence concerning emotions and the interactional context of the classroom. The empirical study is based on a theoretical model proposed by Ibáñez [3,4,5,6,7], which establishes the relationship among emotions, interactional context and learning. This model makes it possible to operationalise Humberto Maturana’s [1,2] conception of emotions in pedagogical interactions in the classroom. Accordingly, the first qualitative stage uses the model of Ibáñez [3,4,5,6,7] and the indicators of personal and social development of the SIMCE 2018 context questionnaire to raise categories of emotions that can be favourable and unfavourable for learning. Subsequently, these categories were validated by expert judges. In a second quantitative stage, a principal component analysis was carried out to the items selected in the previous phase to identify variables that would help understand the impact of emotions on learning.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Emotions and Learning

The framework of radical constructivism implies an epistemological shift from the understanding of knowledge as an explanation of objective reality to its approach as a construction made by the observer, accordingly to their own structure and experiences. In this way of thinking about knowledge, what is experienced by an observer as external reality is in fact product of an act of distinguishing, in which both what is being distinguished and who makes the distinction emerge in the presence of the experience. Thus, this perspective completely renounces metaphysical realism [8,9].

This perspective implies that knowledge is actively built by the cognitive subject. The function of cognition is adaptive and serves the organisation of the experiential world of the subject, not the discovery of an ontological reality [10]. In that sense, reality depends on the experience of the observer and the stories of previous interactions that have made up their particular world. With this, displacement is both epistemological and ontological and has significant consequences for understanding diversity and learning. Maturana [1] (p. 54) establishes that “there is no absolute truth or relative truth but many different truths in many different domains”.

From this approach, learning is determined by emotions, understood as “dynamic bodily provisions that specify the domains of actions in which animals in general and we humans in particular, operate at any time” [2] (p. 68). Thus understood, emotions depend on the interactional history of the subject and on the characteristics of the context of interactions in which they emerge. If emotion changes, actions change too.

According to this perspective, addressing the relationship between emotions and learning requires directing attention to the particular configurations derived from the subjects’ interactions. At the educational level, Ibáñez [3,4,5,6,7] has called these configurations interactional context, referring to the systems of relationships involving interactions between teacher and students, as well as between student and student, within the classroom. The author states that “the characteristics of this relationship correspond to how the persons involved distinguishing each other” [3] (p. 45). These interactions are influenced by the characteristics of the participants, the school contexts in which they operate and the hierarchy and power relationships that emerge from them. Therefore, achievements in expected learning are affected by the interactive dynamics developed between teachers and students, which are reflected in learning outcomes.

The relationship between emotions and learning has been analysed from perspectives such as that proposed by Pekrun, et al. [11], who have defined a theoretical model on emotions related to achieving academic objectives from the socio-cognitive paradigm. Consequently, Frenzel, et al. [12] argued that emotions positively and negatively influence teaching and learning processes in educational contexts. This relationship between emotions and learning is described, by Ibáñez et al. [3,7], as favourable and unfavourable emotions for learning in the interactive classroom context. Although these conceptions ascribe to different ontological perspectives, they agree on the relevance of the emotional states of teachers and students in the educational process.

In this sense, there are important coincidences between what is conceived as an interactional context and what is now understood as classroom climate, focusing on the social environment where interaction is happening in the educational space [13,14,15]. Different authors define classroom climate as a general concept that groups together factors such as the quality of interactions, their fluidity in complex situations involving environmental and social factors and the characteristics that indicate their condition or state, usually from a community perspective [16,17]. In essence, the classroom is seen as a phenomenon of interaction involving the whole class [18], comparable to a living organ in which the whole exceeds the sum of the parts [19,20]. This conception reveals that every interaction, positive or negative, in the classroom is part of the educational phenomenon [13,21,22].

From the described perspectives of interactional context and classroom climate, interactions between teachers and students are fundamental to school success. If these interactions involve favourable emotions in students, they become central drivers for learning [13], improving aspects such as motivation, participation and commitment [13,14].

Theoretical Model: Favourable and Unfavourable Emotions for Learning

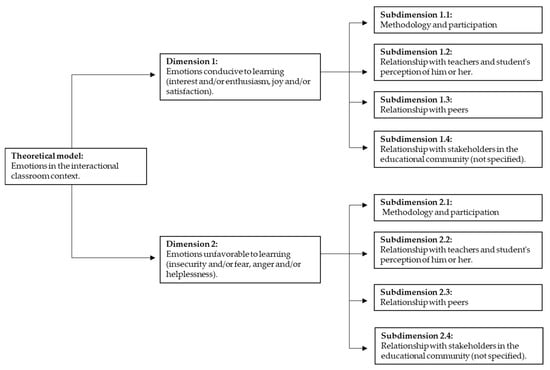

The theoretical model that underpins this study was born in the early 2000s at the Metropolitan University of Education Sciences as a proposal by Professor Nolfa Ibáñez [3,4,5,6,7]. Ibáñez, in her research work, analysed the interactional context in the classroom based on the contextualisation of students’ emotions in specific situations of interaction. These studies sought to operationalise Humberto Maturana’s conception of emotions, observing the pedagogical interactions in the classroom to improve our understanding of their role in sociocultural contexts and student learning. As a result, a categorisation of emotions favourable and unfavourable for learning was obtained. In this regard, favourable emotions include interest, enthusiasm, joy and satisfaction. Unfavourable emotions include insecurity, fear, anger and helplessness. Understanding both types of emotions (favourable or unfavourable) is crucial in the pedagogical field. They would narrow down the actions that students can take at any time, facilitating or hindering their learning processes. When considering favourable and unfavourable emotions as analytical categories, it is possible to establish dimensions such as content and achievement of objectives, methodology and participation, relationship with teachers and student perception of them, and relationship with peers [5].

In this study, we adapted the model proposed by Ibáñez [3]. This adaptation consists of incorporating a new subdimension referring to interaction with unspecified actors in the educational community. In addition, the subdimension relating to personal content and objectives was deleted, since it is not directly observable in the interactional context (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adaptation of the theoretical model proposed by Ibáñez [3].

2.2. System for Measuring the Quality of Education

The International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) act as advisory bodies to implement standardised evaluation systems in different countries. The main task of these bodies is to compare educational policies based on the elaboration of achievement score rankings [23,24]. The International Survey on Mathematics and Science (TIMSS) and the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) are the two most widely used evaluations globally.

Different authors approach these evaluations from a critical perspective [25,26,27,28,29,30], arguing that limitations can be attributed to ways of valuing information. This is because they do not consider other factors such as the importance of “soft skills” and the results are not associated with the academic context or the nature/non-naturalness of the evaluation according to previous training sessions [30] (p. 16). A study by the Inter-American Development Bank comparing different global standardised measurement systems aligns with these concerns, concluding that it is necessary to include variables that comprehensively measure various dimensions of the educational process carried out in schools to complement standardised test results [31].

It is also stated that these evaluations should be inclusive and accessible to all students. However, since this specific aspect is not considered, the information obtained becomes insufficient as an explanatory tool for the community’s decision making [32].

The Chilean Case

At present, SIMCE is a measure of the “effectiveness” of schools. The OECD (2004) stated that its primary objective is to identify low-performing establishments to invest additional resources and monitor their effectiveness. This measurement system contemplates a set of instruments and indices that provide information on integral aspects of the student training to guide institutions to propose improvements to expand the view of the educational quality of the establishment [33] (p. 7). Thus, this system establishes an adjustment process to evaluate performance categories based on performance indicators. Of these indicators, 67% are associated with content learning. In comparison, 33% are related to factors such as academic self-esteem and school motivation, the climate of school coexistence, citizen participation and training, healthy lifestyle habits, school attendance, school retention, gender equity in learning and professional technical qualification [33] (p. 8). Although this instrument has been used as the main measure of quality and improvement of schools in Chile, various voices raise questions about its efficacy [34,35].

Acuña Ruz, et al. [36], for example, consider that this system has become a fundamental pillar of educational institutions but does not reflect the particularities of each community. In addition, from teachers’ perspective, it is an instrument that conditions their performance and affects them concerning the real interests promoted by the Education Quality Agency. In turn, Rappoport and Mena [32] argue that complete information is not accessed through SIMCE as it is not linked to the teaching-learning processes that are being developed. In fact, the inquiries carried out show that its implementation adds impoverishment of pedagogical experiences and stigmatisation of municipal schools, their teachers and students [37,38,39].

3. Materials and Methods

This research study aims to construct a measurement system to assess favourable and unfavourable emotions for learning, based on the questionnaire of personal and social development indicators applied to students in the SIMCE 2018 [40].

This research study is exploratory with a non-manipulative empirical design. The approach is of a mixed sequential-derivative type. The first phase was of qualitative information collection and the second phase corresponded to the quantitative process. The results were integrated through a complex analysis process that considered the findings of both phases [41,42,43].

3.1. Literature Review

Data Sources, Search Strategy and Exclusion Criteria

A systematic literature search was conducted in the following databases: WoS and Scopus. The search criteria employed was that the following terms were included in the study title, abstract or keywords: “Emotion*”; “Classroom climate” or “Classroom atmosphere” or “Emotional climate”; Learning AND outcome* or performance. Our results are relative to the English language studies published between January 2010 and December 2020.

The peer-reviewed articles were selected considering the application of the following standardised set of inclusion criteria: (a) methodological design (empirical papers that describe research methodology); (b) theorical relevance (papers that approach the subject matters of emotions, classroom climate, interactional context and students’ learning process); (c) connecting to academic performance (papers that approach the subject matters of emotions, classroom climate, interactional context and students’ learning process). All articles identified by the search were distributed among N.C.-Q., D.R.-S., S.D.-I. and J.C.-M. in a similar quantity to be independently reviewed. This first revision included the title and abstracts of each one of the unique papers, which were then discussed to select the articles considered potentially relevant. After the inclusion criteria of theorical relevance had been applied, the selected articles were retrieved for full-text review. Four authors (N.C.-Q., D.R.-S., S.D.-I. and J.C.-M.) independently reviewed each of these papers for inclusion. All the inclusion criteria were discussed until all reviewers agreed to include a paper.

3.2. Content Analysis and Validation through Expert Judgement

Expert judges carried out content validation to make the qualitative process more rigorous. The judges were asked to evaluate a sample of 57 items to verify the coherence and consistency of the re-categorisation of the items of the questionnaire of indicators of personal and social development applied to SIMCE 2018 students, with the theoretical model employed.

Ten expert judges were asked to carry out the content validation considering the theoretical model. The criteria for selecting and including judges were: (i) academic degree of PhD, (ii) working in educational research in Chilean universities in different parts of the country and (iii) knowledge of the paradigm of radical constructivism.

The evaluation by experts’ judges was carried out individually without the judges having contact with each other. The Google Forms platform was used to construct an online response form, which contained the following sections: presentation of the research team, summary of the research, ethical considerations, collection of data from the evaluating judge, summary of the theoretical model, guidelines for the validation process and items.

The content validation by expert judges was carried out by means of the IVC content validity index, with a minimum CVC (content validity criterion) of 0.62 (acceptable to maintain an item) considering 10 expert judges.

3.3. Statistics

The “FactoMineR”, “FactoInvestigate”, “ggplot2”, “corrplot” and “rcmdr” R packages were employed to perform the correlation analysis correlogram and to assess the principal component analysis (PCA) as exploratory modelling [44]. We conducted analyses of internal consistency using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 [45].

The participants were associated with the SIMCE 2018 database for the mathematics, reading and natural sciences domains, with a population of 212,999 for second-grade high school students [40]. The students’ population who answered the student questionnaire in the SIMCE 2018 process corresponded to 202,259. The distribution of students’ population corresponded to 2930 establishments, representing 99.2% of those teaching the second grade of high school in the country. For the participants’ selection, the two criteria used were (i) the score for each domain (mathematics, reading and natural sciences) and (ii) the valid value for each item of the student questionnaire (193 items).

4. Results

4.1. Literature on Emotions, Learning and Classroom Interactional Context

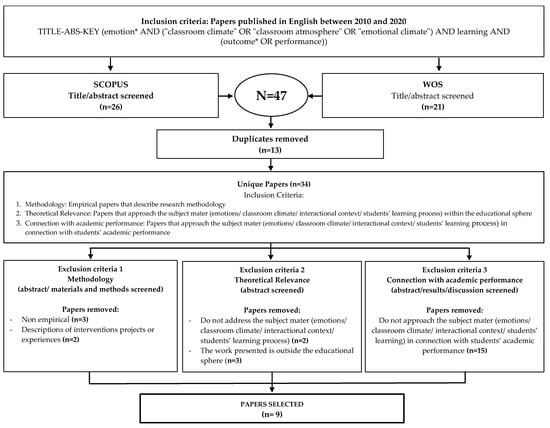

In the literature review process, 47 documents were identified in both databases, including duplicates (Scopus, n = 26; WoS, n = 21). After the exclusion of duplicate items, the search result was reduced to 34 unique articles for review. The complete articles were obtained and examined according to inclusion criteria such as methodology, theoretical relevance and relationship among the concepts of emotion, classroom climate and interactional context concerning the academic performance obtained by students. The researchers S.D.-I. and J.C-M. made all the decisions, but any questions were discussed in the research team. As a result, nine articles met the inclusion criteria for this review, synthesised in Table A1 (Appendix A). Figure 2 shows a flow diagram with the relationship among the steps, criteria and results of the selection process of articles.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram for the selection process of articles.

The results obtained in the systematic review reported nine articles corresponding to research studies that examined different educational levels (kindergarten, primary, secondary and undergraduate) and which, methodologically, used the quantitative approach. These articles highlighted the importance of the classroom climate and interactions as positive factors that contribute to students’ learning outcomes. In this regard, Meyer and Eklund [46], Wayne, et al. [47] and Bove, Marella and Vitale [14] showed a relationship between classroom climate and academic performance, which is also apparent from studies using data derived from PISA 2012 and 2015 [48].

Regarding the relationship between peers and actors in the educational community, we can explore three predictive variables of improved academic performance associated with the classroom climate: emotional support, class organisation and instructional support [48].

The relationship between motivation and academic performance is discussed in research by McCormick, et al. [49], Schenke, et al. [50], Rusticus, et al. [51] and Allen, Hamre, Pianta, Gregory, Mikami and Lun [48]. In recent years, Rohatgi and Scherer [25], in their research study, focused on the students’ perception of their teachers and the motivation that this generates for academic achievement, which is consistent with the relationship between social and emotional learning and the risk of academic failure proposed by Cipriano, et al. [52].

Finally, this literature review summarises some evidence showing the importance of deepening our understanding of the interactions that favour the classroom climate, learning and results.

4.2. Content Analysis and Consistency with the Theoretical Model

The content analysis reviewed and re-categorised 193 items related to the context questionnaire’s personal and social development indicators applied to students [53]. Table 1 shows the results obtained in this review process, which allowed us to identify 57 items consistent with our adaptation of the theoretical model proposed by Ibáñez [3] (Figure 1). Then, ten expert judgement assessments of all 57 items and eliminated 19 of these items. A total of 37 items met the inclusion criteria in good accordance with the theoretical model (Table 1). These items showed that they were sufficiently related and could be reduced to generate three factors interpreted as emotion indices, which could be associated with favourable and unfavourable emotions for learning. The motivation interaction index, exclusive interaction index and interactional context index corresponded to 11 items, 19 items and 7 items, respectively.

Table 1.

Emotion dimensions.

4.3. Favorable and Unfavourable Emotion Indices for Learning

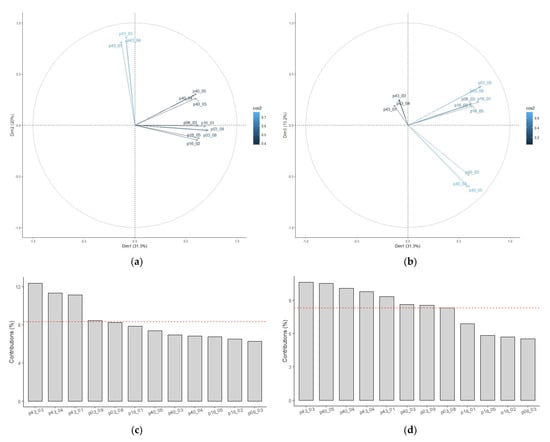

Sample participants who met the selection criteria corresponded to 38,454 for second-grade high school students. With this sample, 37 items grouped in three emotion indices were evaluated by the PCA method. In order to avoid redundant information, the 37 items of the context questionnaire were reduced to the 12 items that contributed the most variance to the data set. This exploratory method separated our items set into three groups that correlate well with the emotion indices.

Only three principal components (PCs) were sufficient to explain the 64.5% of variance of the scores. Figure 3 shows the PC score graph using these 12 items. It indicates that only the first, second and third components were necessary to obtain a good classification of favourable and unfavourable emotion indices for learning. The first component divided the items into two subsets. The positive region of the PCA graph of items on the first PC mainly contains items related to favourable emotion, such as motivation arising from interaction and interactional context indices. The first is characterised by the presence of items related to the teachers’ praxis. The second is related to the student’s perception of their opinions’ relevance because something is interesting and worth knowing in the class. In contrast, the negative region contains the items that describe unfavourable emotions related to fear and nervousness.

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis graph of items: (a) Dimension 1 and Dimension 2; (b) Dimension 1 and Dimension 3; (c) contributions of variables to Dimensions 1–2; (d) contributions of variables to Dimensions 1–2–3. Dim = Dimension; In the parentheses, cumulative variance is shown.

The best classification of favourable and unfavourable emotion for learning was obtained using the first and second components (see Figure 3). This representation shows that the first component opposes individuals characterised by a strongly positive coordinate on the PC1 (to the right) to individuals characterised by a negative coordinate on the PC1 (to the left). Consequently, motivation arising from the interaction is characterised by a positive coordinate on the axis with high values for items such as p40_04, p40_05, p40_03, p16_01, p03_09, p03_08 and p06_03 (sorted from the strongest to the weakest). Similarly, the interactional context is characterised by a positive coordinate on the axis with high values for items such as p16_02 and p16_05 (sorted from the strongest to the weakest). These two subsets were associated with favourable emotions.

These three emotion indices resulted in acceptable reliability scores measured by a Cronbach’s α of 0.803 (motivation interaction), 0.852 (exclusionary interaction) and 0.831 (interactional context), respectively. The Cronbach’s α‘s coefficients, for each emotion index, clearly indicate the reliability of their set of items to measure the underlying dimension of that index. The Cronbach’s α’s weighted average reached a value of 0.820, which shows the high reliability of this set of indices to measure the motivation interaction, exclusionary interaction and interactional context underlying dimensions that it contemplates.

Consequently, the indicators of personal and social development obtained from the context questionnaire (student questionnaire) applied to students at the SIMCE 2018 is an instrument that allows us to identify variables associated with favourable and unfavourable emotions for learning. According to these results, these emotions indices can be used for the first approximation in the emotions characterisation in school using the questionnaire context information. In this regard, the first and third indices would represent the emotions of interest, enthusiasm (joy) and satisfaction. In contrast, the second item would describe emotions of insecurity, fear, anger, nervousness and frustration. In each of the three indexes, the relationships between emotions and interactions are represented in the classroom, reflecting the systemic dimension of the relationship emotions–interactional context involved in the proposed theoretical model, whose concrete representation is likely to be measured through the indicators of social and personal development of the SIMCE.

5. Discussion

This research study indicates that favourable and unfavourable emotions for learning, in the interactional context of the classroom, constitute a variable in the indicators of personal and social development contained in the questionnaires applied to students in the SIMCE 2018. Therefore, the objective of conducting a mixed analysis of the variables extracted from these indicators for constructing a measurement system using indices that allow us to evaluate the favourable and unfavourable emotions for student learning was met.

The variables identified through the content and construct validation processes made it possible to corroborate the theoretical model capability to contribute to understanding the SIMCE 2018 results. This is especially relevant if we consider that the results of recent research studies highlight the explanatory and predictive value of emotions and the interactional context in students’ academic performance [14,25,47,48]. This information reveals an urgent need for mechanisms that allow for cross-sectional measurements in the national educational context to be conducted.

This study verifies the coherence between the systematic review of the literature and the consistency of the three indices identified through a statistical process and the favourable and unfavourable emotions for learning that are the main analytical categories of the theoretical model. Thus, the first index (motivation arising from interaction) and the third index (interactional context) would represent emotions of interest and/or enthusiasm and joy and/or satisfaction, while the second index (exclusionary interaction) would represent emotions of insecurity and/or fear and anger and/or frustration. In each of the three indices, the relationships between emotions and interactions in the classroom are represented, reflecting the systemic dimension of the emotions–interactional context linkage, implied in the proposed theoretical model, whose concrete representation is susceptible to be measured through the personal and social development indicators of the SIMCE 2018.

The indices show that the items evaluated reflect favourable and unfavourable emotions for learning (Table 2). The first index (motivation arising from interaction) points to the key role played by teachers in motivating students to face the learning process in a positive way, as well as in the explanatory communicative didactic action. In contrast, the second index (exclusionary interaction) alludes to the students’ difficulties in the educational process in the face of emotions such as fear and/or insecurity, since they constitute barriers to learning. The third index (interactional context) shows the relevance of the students’ participation as active subjects in a democratic context, making interactions favourable to make learning possible.

Table 2.

Favourable and unfavourable emotion indices.

Our findings confirm the results of previous research works on the feasibility of using international standardised assessment systems such as PISA [14,25] to assess the correlations among emotions, interactional context and academic performance. Particularly, Bove, Marella and Vitale [14] note that school and classroom climate, together with the teacher’s behaviour, influence academic performance in the mathematics-specific test in PISA 2012.

Rohatgi and Scherer [25], in a study applied to the PISA 2015 test, identify student profiles that reveal negative perceptions of bullying and poor academic performance associated with unfair treatment by teachers, as well as positive perceptions of school climate variables. This allows us to insist that standardised measurements make it possible to observe favourable and unfavourable emotions for learning, since the interactional context or classroom climate contains these perceptions and they are noticed by students.

The research studies considered in our literature review also shows significant relationships between classroom climate and students’ academic performance [14,46,47,48]. These studies show that the favourable emotions present in the interactional context allow better learning to happen, which coincides with the theoretical model proposed in this research study; the interactional context improves from the support that teachers provide to their students, with a positive impact on academic performance. This demonstrates the importance of favourable emotions in the interactional context [3,6,48,54,55].

The favourable emotions arising from positive interactions between students and teachers would positively impact students’ motivation and performance and their perceptions of their teachers. For example, Allen, Hamre, Pianta, Gregory, Mikami and Lun [48] conclude that the specific interactions observed between teachers and students and academic performance positively impact learning, regardless of the content being taught. Thus, the interactional context developed based on favourable emotions improves the learning environment, enabling a harmonious relationship between teachers and students and among students [48,49,50]. As a result, students’ satisfaction and engagement with their own educational process increase [14,15].

6. Conclusions

Emotions are considered fundamental in understanding the teaching and learning processes. An instrument such as SIMCE, through its questionaries, offers the possibility of collecting data related to the interactional context and the emotions that arise from it. This study shows a new way of analysing the information obtained by this instrument, allowing emotions to be incorporated into the interactional context to explain academic performance measured with standardised evaluation systems. In doing so, the work discussed here identifies three indexes of emotions generated with the information contained in personal and social development indicators of the SIMCE. Moreover, it is shown that, through these indices, it is possible to measure aspects related to emotions and the interactional context of the classroom to understand the incidence of emotions in school learning.

The research process and results discussed here facilitate identifying the diversity of emotions that affect learning, which is also a reflection of the heterogeneity of students that make up a school community. This type of information can be useful for teaching teams and researchers in providing students with specific support to strengthen their positive perceptions, academic performance and even improve the classroom climate.

This study invites the academic and scientific community to expand research on favourable and unfavourable emotions for learning at all educational levels where the SIMCE assessment instrument is applied. Results of such research works could contribute to decision making at the public policy level to improve the quality of Chilean education based on the resources available in the SIMCE test.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, D.R.-S. and S.D.-I.; methodology, N.C.-Q., S.D.-I. and J.R.-B.; software, N.C.-Q., S.D.-I. and J.R.-B.; validation, N.C.-Q., D.R.-S. and S.D.-I.; formal analysis, N.C.-Q., D.R.-S. and S.D.-I.; internal investigation, N.C.-Q., D.R.-S. and J.C.-M.; internal research, N.C.-Q., D.R.-S., S.D.-I. and J.C.-M.; resources, S.D.-I. and J.C.-M.; data curation, N.C.-Q., D.R.-S. and J.R.-B.; original writing—drafting, N.C.-Q. and D.R.-S.; writing—revising and editing, N.C.-Q., D.R.-S. and J.R.-B.; supervision, N.C.-Q., D.R.-S. and J.R.-B.; project administration, N.C.-Q. and D.R.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

D.R.-S. and S.D.-I. were funded by Programa Extraordinario de Becas de Postgrado—Doctorado en Educación—UMCE. The APC was funded by Universidad Metropolitana de Ciencias de la Educación trought of programe Fondo de Incentivo a las Publicaciones WoS, Scopus y Scielo-Chile.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the databases used are publicly archived under Law No. 20.285 and were requested on 17 August 2019, in request No. AJ012T0000971. The access was approved in letter 1215 on 3 September 2019. The databases provided by the Agencia de la Calidad de la Educación—Chile are subject to prior information processing to safeguard the anonymity of the data, following the provisions of Law No. 19.628, on the Protection of the Private Life of the State of Chile.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Restricted access databases must be requested in https://informacionestadistica.agenciaeducacion.cl/#/bases (accessed on 18 November 2021).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Programa Extraordinario de Becas de Postgrado—Doctorado en Educación—UMCE and Tatiana Díaz Arce, for their comments on the initial version of this manuscript. This research study used the databases of the “Agencia de Calidad de la Educación” as a source of information. The authors thank the “Agencia de Calidad de la Educación” for access to information. All the study results are the responsibility of the author and do not compromise said institution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the study’s design, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Synthesis of literature review.

Table A1.

Synthesis of literature review.

| Research Aims | Methodology | Results | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context | Method (QUAN/QUAL) | Description | Methodological Tools to Assess Relationships among Emotions, Interactional Context and Learning | ||||

| Participants | Educational Level | ||||||

| To evaluate a mindfulness intervention effects on classroom climate and academic outcomes, particularly regarding rading fluency. | 14 school classrooms of 4th and 6th grade | Primary | QUAN | Quasi-experimental design (treatment and control group). Pre- and post-tests (controlling for confounding variables) to test the relationship between the intervention aimed at promoting emotional climate and classroom interactions and reading fluency achievement level. | Academic performance—reading fluency achievement level measured with Reading and Analysis Prescription System 360 (RAPS 360; MindPlay 2012). The potential impact of participation in the mindfulness intervention on reading fluency was measured using ANDEVA. | The results associated with time were significant (Wilk’s lambda = 0.98, F (1, 286) = 6.44, p = 0.012, partial eta squared = 0.0). | Meyer and Eklund, 2020 |

| 596 students | Increased reading fluency was observed in control and treatment groups with no significant differences between them. | ||||||

| 158 male 138 female | In subsequent measurements, the treatment group showed greater increases in fluency, but this difference was not statistically significant and could not be directly attributed to intervention participation. | ||||||

| To examine associations between RULER (SEL program) and changes in student engagement, conduct and academic achievements. | 64 schools in one school district (n = 318 students) | Diverse student population, preferably in early adolescence, in the northeast of the EEUU | QUAN | Analysis of multiple theoretical trajectories, with control and treatment group. | Student engagement was assessed by student report on the Engagement vs. Disengagement Scale (10 items; alpha, 0.89; Furrer and Skinner, 2003) and student reports of classroom climate and school motivation (Skinner et al., 2008). Academic performance was measured by calculating students’ academic subject grade point averages (GPA). Student behaviour was obtained using teacher reports. | Significant relationships between participation and behaviour in 5th grade for the control group and the RULER group were found; only the students who participated in RULER showed improvements in participation in sixth grade and in behaviour in seventh grade. No significant relationships were found between participation and academic achievement. | Cipriano et al., 2019 |

| To test whether students’ participation in INSIGHTS tasks improved low socio-economic pre-school and first grade students’ achievement in mathematics and reading, through the prior improvement of emotional support and classroom organisation. | 120 teachers and 435 students/parents duple in 22 public schools | Pre-school and primary education | QUAN | Randomised testing of school programmes. Multilevel regression analysis, instrumental variables estimation and inverse probability of treatment weight (IPTW) were conducted. Pre- and post-tests were conducted to test the potential impact of intervention participation on improving classroom emotional and organisational climate and student outcomes. | The emotional climate considered 4 dimensions of pedagogical practices: positive and negative climate, teacher sensitivity and consideration of students’ perspectives. Independent measurements were made of the relevant variables grouped as follows: (a) Variables of outcome—achievement in reading and mathematics measured through total scores on the LetterWord Identification and Applied Problems subtests of the Woodcock–Johnson III Tests of Achievement, Form B (Woodcock, McGrew, and Mather, 2001). (b) Variables of mediation emotional support and classroom organisation—measured using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS; Pianta, La Paro, et al., 2008). | For pre-school there was no evidence of correlation. For first grade, emotional support was associated with higher achievement levels in mathematics (B = 0.89, SE = 0.38, p = 0.02), as was classroom organisational climate (B = 0.97, SE = 0.40, p = 0.0) There were no statistically significant relationships for reading. | MacCornick et al., 2015 |

| The results show that the INSIGHTS programme improved the climate of emotional support in the classroom and that, subsequently, this positively impacted first grade students’ academic achievement in mathematics. | |||||||

| To examine the role of teacher–student interactions in the classroom highlighting when they are predictive of academic achievement and also when they reflect pre-existing student characteristics. | 643 students in 37 classrooms in (11 schools in 6 districts) | Secondary school | QUAN | Hierarchical linear modelling (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002) was used as the conceptual and analytical framework for specifying two-level models examining the association between measures of classroom quality and students’ outcomes. | Observation of standardised classroom interactions using a modified version of the CLASS system, including domains of emotional support (positive climate, negative climate, teacher sensitivity and adolescent perspectives subscales), classroom organisation (behaviour management, productivity and instructional formats subscales) and instructional support (content comprehension, analysis and problem solving and quality of feedback subscales). Student achievement was measured using the Standards of Learning (SOL; Commonwealth of Virginia, 2005). | All three domains (emotional support, classroom organisation and instructional support) were predictors of improvement of academic performance. | Allen et al., 2013 |

| The strongest predictor was the emotional support domain. Class size interacted with emotional support (B = −4.81, SE = 2.00, p = 0.02) and instructional support (B = −3.54, SE = 1.78, p = 0.046), such that both emotional support and instructional support increased in predictive value for students in smaller classrooms compared to those in larger classrooms. | |||||||

| To assess the effect of students’ perception of the learning environment on their performance on a standardised licensing test controlling for prior academic ability. | N = 267 | Higher education | QUAN | The results of students’ assessment of their learning environments were contrasted with their performance on Step 1 of the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE). | Students’ perceptions of their learning environments were assessed using the previously validated Learning Environment Questionnaire (LEQ) (Moore-West et al., 1989), which contains 5 subscales: meaningful environment, emotional climate, student–student interaction, nurturance and flexibility. A linear regression was performed for each sub-scale of the applied test, including MCAT scores, GPA and gender in each model. | Three of the five learning environment subscales were statistically associated with Step 1 performance (p < 0.05): meaningful learning environment, emotional climate and student–student interaction. A one-point increase in subscale scores (1–4 scale) was associated with increases of 6.8, 6.6 and 4.8 points on the Step 1 test. The findings provided evidence for the generalised assumption that a positively perceived learning environment contributes to better academic performance. | Wayne et al., 2013 |

| To examine whether (i) heterogeneity in students’ perceptions of classroom climate is related with their achievements in mathematics and (ii) heterogeneity in perceptions of classroom climate among students in the same grade is associated with academic achievement. | N = 1604 82 math classrooms in 10 public schools | Primary | QUAN | A latent profile analysis was conducted to characterise students’ perceptions of the classroom. Based on it, a model of five profiles was generated. Next, a measure of the heterogeneity of the profiles within each classroom was generated. Finally, multilevel modelling was conducted. | (1) Perceptions of classroom climate were collected through questionnaires and (2) performance was measured using mathematics class grades. Controls for prior mathematics performance, ethnicity, number of students per grade and gender. | Five student profiles were identified: 1. high Achievement focus (8%), 2. medium emotional support and high achievement (6%), 3. low emotional support (22%), 4. high emotional support (57%), 5. high emotional support and autonomy support (7%). The first and third profiles were negatively correlated with achievements in mathematics (r = −0.12, p=0.001 and r = −0.11, p = 0.001, respectively) and the fourth profile was positively correlated with achievements in mathematics (r = 0.14, p = 0.001). The level of heterogeneity of students’ perceptions of classroom climate within the same course was negatively related to the mathematics achievements of the course as a whole. | Schenke et al., 2017 |

| To assess the seven scales of medical interest: personal interest, emotional climate, flexibility, meaningful learning experience, organisation, support and student–student interaction. | 311 medical students (40%): 1st year, 120; 2nd year, 102; 3rd year, 89. Gender proportionality: 45.3:54.7 Age variation: from 20 to 42 years of age (M = 27.7, SD = 3.7). | Higher education | QUAN | A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to test a 5-factor model for learning environments, assessing the correlation between its dimensions and students’ satisfaction and performance. | (a) Medical School Learning Environment Survey (MSLES). (b) Student satisfaction, measured on a seven-point scale. (c) Academic performance: the overall grade of students at the end of their respective year. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to support the validity of the MSLES when used with this sample. Correlations between the dimensions of learning environment, student satisfaction and achievement were calculated using Pearson correlations. | Positive correlations were detected between learning environment and academic performance and between learning environment and student satisfaction. The correlation was significant but weak (0.10–0.29). | Rusticus et al., 2014 |

| Examining the influence of classroom climate and teacher behaviour on the Italian students’ results in the PISA 2012 test. | 16,709 15 years old students (8276 male and 8433 female) | Secondary | QUAN | Classroom climate and teacher behaviour were assessed as predictors of student outcomes, accounting for differences in the sample sizes. Multilevel regressions with two levels and random intercepts were performed with the Mplus software (V6) and the plausible value estimation method (5 levels) was incorporated. | Aggregate mathematics achievement percentages from the PISA test were used. Classroom climate and teacher behaviour were obtained at two levels. The student level—items were selected from various background questionnaires included in the application of the PISA test. These items were included in the following indices: (i) disciplinary climate index; (ii) the teacher–student relations index; (iii) teacher direct instruction index; (iii) student orientation index; (iv) formative assessment use index; (v) cognitive activation strategies use index. Indices were also used at the school level, incorporating responses from principals and students. | The perception of classroom climate and teacher behaviour significantly affected students’ academic performance in the PISA test. The classroom climate index positively affected mathematics performance (regression coefficients of 2.77 and 13.82). Individual results overlapped with those obtained at the school level (the performance of a student who perceived a good classroom climate increased if he or she belonged to a school with better results on classroom climate). The teacher–student relations index had a negative impact on mathematics achievements at both levels. The aggregate of the four indices referring to teaching behaviour was statistically significant. The index referring to the use of cognitive activation strategies was significantly positively correlated with mathematics achievements. In this case, the results at school level also overlapped with an additive effect. This index showed the strongest positive correlation with students’ academic results (increase of 28 points on average); it was followed by the classroom climate index (increase of 16 points). Significant negative effects were observed in relation to the student orientation index (−22 points), use of formative assessments (−14 points) and direct teacher instruction (−14 points). This means that teacher behaviours and classroom climate that students perceived as characterised by frequent use of student guidance, use of formative assessments and direct instruction were significantly associated with lower achievement levels in mathematics. | Bove et al., 2016 |

| To examine patterns of school climate as perceived by students and their relationship with educational outcomes. | N = 5313 students (50.2% of female students is represented) | Most students attended the tenth grade. Less than 1% were ninth graders. | QUAN | Using a sample of Norwegian students who took the PISA test in 2015, the study integrated different stages of analysis aimed at identifying latent profiles of students’ perceptions of school climate (using the person-centred latent profile analysis approach), establishing the extent to which some of the students’ background variables determined their belonging to each profile and, finally, exploring differences between the profiles in educational outcomes, including science achievement and achievement motivation. | Students rated their opinions on a four-point Likert scale. The responses were used as overt indicators of a latent variable representing the underlying trait in PISA 2015. | Three profiles were evident: (1) students with consistently positive perceptions, (2) students with moderately negative perceptions and (3) students with extremely negative perceptions, especially with regard to teacher fairness and bullying. A strong correlation was detected between the identified profiles, and academic achievement and motivation in science. In relation to science achievement, the difference between profile 1 (M = −0.526, SD = 0.988) and profile 2 (M = 0.059, SD = 0.988) was significant (d = −0.592, 95% CI between −0.702 and −0.482), as well as between profile 1 and 3 (M = 0.040, SD = 0.988; d = −0.573, 95% CI between −0.676 and −0.470). The difference between profile 2 and 3 was not significant (d = 0.019, 95% CI between −0.041 and 0.079). | Rohatgi and Scherer, 2020 |

References

- Maturana, H. Emociones y Lenguaje en Educación y Pólitica; Sáez, J.C., Ed.; Dolmen: Santiago, Chile, 1990; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H. La Realidad: Objetiva o Construida?: I.Fundamentos Biológicos de la Realidad; Anthropos Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 1995; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez, N. El Contexto Interaccional En El Aula: Una Nueva Dimension Evaluativa. Estud. Pedagógicos 2001, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, N. Las Emociones En El Aula. Estud. Pedagógicos 2002, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, N. Aprendizaje-enseñanza: Mejora a partir de la interacción de los actores. Educación y Educadores 2011, 14, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, N.; Barrientos, F.; Delgado, T.; Figueroa, A.M.; Gueisse, G. Las emociones en el aula y la calidad de la educación. Pensam. Educ. Rev. de Investig. Educ. Latinoam. 2004, 35, 292–310. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez, N.; Barrientos, F.; Delgado, T.; Gueisse, G. La Disposición Emocional en el Aula Universitaria como Factor Relevante en la Formación Docente; DIUMCE: Santiago, Chile, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- von Glasersfeld, E. Introducción al constructivismo radical. In La Realidad Inventada; Watzlawick, P., Ed.; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 1994; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- von Glasersfeld, E. Despedida de la objetividad. In El ojo del Observador. Contribuciones al Constructivismo; Watzlawick, P., Krieg, P., Eds.; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 1995; pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, C.; Amador, L.F.G.; Díaz, B.L.P.; Moreno, C.P. Límites del constructivismo pedagógico. Educ. y Educ. 2006, 9, 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R.; Elliot, A.J.; Maier, M.A. Achievement goals and discrete achievement emotions: A theoretical model and prospective test. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, A.C.; Goetz, T.; Lüdtke, O.; Pekrun, R.; Sutton, R.E. Emotional transmission in the classroom: Exploring the relationship between teacher and student enjoyment. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardach, L.; Lüftenegger, M.; Yanagida, T.; Schober, B.; Spiel, C. The role of within-class consensus on mastery goal structures in predicting socio-emotional outcomes. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 89, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, G.; Marella, D.; Vitale, V. Influences of school climate and teacher’s behavior on student’s competencies in mathematics and the territorial gap between Italian macro-areas in PISA 2012. J. Educ. Cult. Psychol. Stud. 2016, 2016, 63–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamlem, S.M. Mapping Teaching Through Interactions and Pupils’ Learning in Mathematics. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 215824401986148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.; Asgari, A. Predicting Students’ Academic Achievement Based on the Classroom Climate, Mediating Role of Teacher-Student Interaction and Academic Motivation. Integr. Educ. 2020, 24, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, C.; Alonso-Tapia, J. Positive Classroom Management: Effects of Disruption Management Climate on Behaviour and Satisfaction with Teacher// Clima positivo de gestión del aula: Efectos del clima de gestión de la disrupción en el comportamiento y en la satisfacción con el profesorado. Rev. Psicodidact./J. Psychodidactics 2015, 21, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizir, S. The Sense of Classroom Belonging Among Pre-Service Teachers: Testing a Theoretical Model. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 8, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilam, E. Synchronization: A framework for examining emotional climate in classes. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, A.; Ahtee, M.; Näveri, L. Impact of Teacher’s Actions on Emotional Atmosphere in Mathematics Lessons in Primary School. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2020, 18, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.T.; Solheim, O.J. Exploring associations between supervisory support, teacher burnout and classroom emotional climate: The moderating role of pupil teacher ratio. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 40, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J.-M.; Dewaele, L. Are foreign language learners’ enjoyment and anxiety specific to the teacher? An investigation into the dynamics of learners’ classroom emotions. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2020, 10, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, D. Sistemas de medición de la calidad educativa a nivel nacional e internacional. Rev. Educ. Andrés Bello 2015, 2, 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Cano, A. A methodological critique of the PISA evaluations. RELIEVE Rev. Electron. Investig. Eval. Educ. 2016, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, A.; Scherer, R. Identifying profiles of students’ school climate perceptions using PISA 2015 data. Large-Scale Assess. Educ. 2020, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verger, A.; Parcerisa, L.; Fontdevila, C. The growth and spread of large-scale assessments and test-based accountabilities: A political sociology of global education reforms. Educ. Rev. 2019, 71, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, C.d.C.; Rojas, D.F.; Salcedo, P.A. Un Método para Analizar Datos de Pruebas Educacionales Estandarizadas usando Almacén de Datos y Triangulación. Form. Univ. 2018, 11, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Betancour, M. El PISA y su impacto en la política educativa en los últimos dieciséis años. Pensam. Educ. Rev. de Investig. Latinoam. (PEL) 2020, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Zincke, C. Evaluation device and governmentality of the educational system: Intertwining of social science and power. Cinta Moebio 2018, 61, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaia, A.; Cadena, A.; Child, F.; Dorn, E.; Krawitz, M.; Mourshed, M. Factores que Inciden en el Desempeño de los Estudiantes: Perspectivas de América Latina 2017; McKinsey and Company, 2017; p. 57. Available online: https://www.calidadeducativasm.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Factores-Desempe%C3%B1o.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Elacqua, G.; von der Fecht, M.M.; Sofie, W.O.A. Diseño de Índices de Calidad Escolar: Lecciones de la Experiencia Internacional; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rappoport, S.; Mena, M.S. Inclusión educativa y pruebas estandarizadas de rendimiento. Revista de Educación Inclusiva 2017, 8, 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Agencia de la Calidad de la Educación. Los Indicadores de Desarrollo Personal y Social en los Establecimientos Educacionales Chilenos: Una Primera Mirada. Available online: https://archivos.agenciaeducacion.cl/estudios/Estudio_Indicadores_desarrollo_personal_social_en_establecimientos_chilenos.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Ruminot, C. Los Efectos Adversos de una Evaluación Nacional sobre las Prácticas de Enseñanza de las Matemáticas: El Caso de SIMCE en Chile. Rev. Iberoam. de Eval. Educ. 2017, 10, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ramos-Zincke, C. Dispositivo de evaluación y gubernamentalidad del sistema educacional: Entretejimiento de ciencia social y poder. Cinta Moebio 2018, 61, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña Ruz, F.; Mendoza Horvitz, M.; Rozas Assael, T. El hechizo del SIMCE. Rev. Chil. de Pedagog. 2019, 1, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIDE. IX Encuesta a Actores del Sistema Educativo 2012. Universidad Alberto Hurtado. Available online: http://www.cide.cl/documentos/Informe_IX_Encuesta_CIDE_2012.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Oyarzún Vargas, G.; Flórez Petour, M. Resultados SIMCE y Plan de Evaluaciones 2016–2020: Nudos críticos y perspectivas de cambio. Cuad. de Educ. 2016, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bellei, C. Expansión de la educación privada y mejoramiento de la educación en Chile. Evaluación a partir de la evidencia. Pensam. Educ. Rev. de Investig. Latinoam. (PEL) 2007, 40, 285–311. [Google Scholar]

- Base de Datos de la Agencia de Calidad de la Educación 2018; Agencia de Calidad de la Educación: Santiago, Chile, 2018.

- Ramírez-Montoya, M.; Lugo-Ocando, J. Systematic review of mixed methods in the framework of educational innovation. Comunicar 2020, 65, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez Moscoso, J. Los métodos mixtos en la investigación en educación: Hacia un uso reflexivo. Cad. de Pesqui. 2017, 47, 632–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamui-Sutton, A. Un acercamiento a los métodos mixtos de investigación en educación médica. Investig. en Educ. Méd. 2013, 2, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 25.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, L.; Eklund, K. The Impact of a Mindfulness Intervention on Elementary Classroom Climate and Student and Teacher Mindfulness: A Pilot Study. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 991–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Fortner, S.A.; Kitzes, J.A.; Timm, C.; Kalishman, S. Cause or effect? The relationship between student perception of the medical school learning environment and academic performance on USMLE Step 1. Med. Teach. 2013, 35, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Hamre, B.; Pianta, R.; Gregory, A.; Mikami, A.; Lun, J. Observations of effective teacher-student interactions in secondary school classrooms: Predicting student achievement with the classroom assessment scoring system-secondary. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 42, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, M.P.; Cappella, E.; O’Connor, E.E.; McClowry, S.G. Social-Emotional Learning and Academic Achievement: Using Causal Methods to Explore Classroom-Level Mechanisms. AERA Open 2015, 1, 2332858415603959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenke, K.; Ruzek, E.; Lam, A.C.; Karabenick, S.A.; Eccles, J.S. Heterogeneity of student perceptions of the classroom climate: A latent profile approach. Learn. Environ. Res. 2017, 20, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusticus, S.; Worthington, A.; Wilson, D.; Joughin, K. The Medical School Learning Environment Survey: An examination of its factor structure and relationship to student performance and satisfaction. Learn. Environ. Res. 2014, 17, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, C.; Barnes, T.N.; Rivers, S.E.; Brackett, M. Exploring Changes in Student Engagement through the RULER Approach: An Examination of Students at Risk of Academic Failure. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk 2019, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, G.V. Relating Qualitative Analysis to Equilibrium Principles. J. Chem. Educ. 2001, 78, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriagada, T.D. La disposición emocional en el aula universitaria y su relación con la calidad educativa en la formación inicial docente. Diálogos Educ. 2004, 7, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, H.P.; Ngu, B.H. Schooling experience and academic performance of Taiwanese students: The importance of psychosocial effects, positive emotions, levels of best practice, and personal well-being. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 23, 1073–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).