Abstract

COVID-19 has been one of the most significant disruptors of higher education in modern history. Higher education institutions rapidly transitioned to Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) in mid-to-late March of 2020. The extent of COVID-19’s impact on teaching and learning, and the resulting challenges facilitating ERT during this time, likely varied by faculty, institutional, and geographical characteristics. In this study, we identified challenges in teaching and learning during the initial transition to ERT at Predominantly Undergraduate Institutions (PUIs) in the Midwest, United States. We conducted in-depth interviews with 14 faculty teaching at Midwestern PUIs to explore their lived experiences. We describe the most overarching challenges related to faculty teaching through four emergent themes: pedagogical changes, work-life balance, face-to-face interactions, and physical and mental health. Five themes emerged that we used to describe the most overarching challenges related to students and their learning: learning patterns, technology access, additional responsibilities, learning community, and mental health. Based upon the identified challenges, we provide broad recommendations that can be used to foster a more successful transition to ERT in unforeseen regional or global crises in the future.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 was first identified in Wuhan, China, in December of 2019. Despite early efforts to control the spread of the virus, on 11 March 2020, the novel infectious disease was found in 114 countries and was classified as a pandemic [1]. Led by guidance from scientists and health officials, governments around the world mandated national lockdowns and placed restrictions on the gathering of people to slow the spread of the virus. Daily life was fueled with uncertainty, stress, and anxiety for many as the disease advanced to urban and rural communities around the globe [2,3]. For all but workers deemed as “essential” or “life-sustaining” (e.g., emergency room medical personnel and supermarket staff), business and industry shutdowns led to a surge of employees working from home or being furloughed or laid-off [4]. Similarly, colleges and universities rapidly transitioned to operate in an emergency remote environment [5,6]. By mid-to-late March, most institutions of higher education in the United States made the abrupt shift to operating in a virtual capacity [5]. Additionally, students who lived in campus dormitories were strongly urged or required to return back to their permanent residences (e.g., family residence) if they were able to do so [7]. There were large uncertainties on how the unprecedented pandemic would impact the operations and outcomes of higher education [8,9,10].

In most instances, faculty in higher education were given mere days to transition their courses from an existing face-to-face format to remote instruction. Although online education is becoming more common and accepted in higher education [11,12], a clear distinction exists from formally planned online teaching to what became commonly known as emergency remote teaching (ERT) [13]. In most cases, the pedagogical approaches, learning activities, and assessments that are designed for face-to-face courses do not easily translate to a remote format. This is especially true for courses that emphasize hands-on learning through practicums and laboratory work common in the sciences [10]. Faculty had to quickly adapt their courses to ERT by determining if and how to modify course content, how to evaluate student learning through online assessment, and how to effectively deliver instruction in a virtual capacity. The abrupt transition required universities and faculty to rapidly navigate a variety of technology and modality (e.g., synchronous, asynchronous, hybrid) options, and select the most appropriate tools to facilitate online learning [14]. They also had to consider students’ acceptance, access, and use of the technologies [15,16,17].

Faculty had varying levels of experience teaching remotely and knowing pedagogical practices best suited for online learning, and in particular ERT [18,19,20]. Institutional support and resources available to faculty likely varied by institutional factors such as existing integration of online teaching and technology, degree of information technology support staff, existing resource infrastructure (e.g., internal communities of practice), and financial resources. Sahu (2020) predicted that faculty who were not savvy with technology may not adapt well to online teaching [10], while Christian et al. (2020) added that instructors’ increased stress and workload may impact teaching performance [21]. In some instances, faculty may not have known how long the transition to ERT would last. Bao (2020) recommended that faculty should be prepared for unexpected challenges to emerge during ERT and prepare contingency plans for when issues arise [18].

Existing research on the transitionary period from face-to-face to remote instruction showed that many faculty felt ill-prepared to transition to ERT, but none-the-less made significant modifications to their course operations. Johnson et al. (2020) surveyed nearly 900 faculty and administrators across 672 U.S. institutions to assess changes to instructional delivery in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic [6]. The researchers found that a majority of faculty, regardless of previous experience teaching online, implemented new teaching methods and made changes to their assignments or exams. Hollander et al. (2020) indicated that faculty were largely uncomfortable transitioning their courses due to a perceived lack of training in online pedagogy and educational technology [22]. In late March and in May of 2020, Watermeyer et al. (2021) surveyed 1148 university faculty in the United Kingdom and found that only half of faculty felt prepared to deliver online learning, whereas approximately 60% felt confident in their ability to facilitate online learning, teaching, and assessment [23].

One of the most important aspects and expected challenges transitioning to ERT was student accessibility to the learning environment [20]. Many students were displaced from their campus dormitories and were removed from the traditional learning environment they became accustomed to. Students had to quickly find new housing, which for many meant moving back home to live with their families. The variety of students’ living situations were expected to be immense, ranging from living in remote areas with limited internet access to shared responsibilities caring for siblings. Sahu (2020) described that student access to the remote learning environment extended beyond having reliable internet and included physical technology devices, which were low in supply due to the migration of working and schooling from home [10]. In addition, Rapanta et al. (2020) suggested that cost, privacy, computer requirements, and necessary bandwidth associated with the technologies pose significant barriers to students’ access to ERT [20]. COVID-19 compounded inequalities related to sociodemographics and access to education [19], and threats to racial equity across higher education were exacerbated by the pandemic [24]. Sahu (2020) recommended that faculty needed to be especially flexible and understanding of students’ unique situations during ERT [10].

The negative impacts of COVID-19 extended beyond challenges related specifically to teaching and learning. Students experienced a higher prevalence of psychological distress related to uncertainty and anxiety about their own health, safety, education, and concern for the well-being of their family members [25]. Students also had to cope with isolation and loneliness due to social distancing [26]. Wang et al. (2020) conducted an online survey assessing the mental health of U.S. college students during the onset of the pandemic in 2020 [27]. Out of 2031 undergraduate and graduate respondents, 48.14% showed a moderate-to-severe level of depression, 38.48% showed a moderate-to-severe level of anxiety, and 18.04% had suicidal thoughts. Rudenstine et al. (2020) found a high prevalence of depression and anxiety among a sample of adult college students in an urban, low-income public university sample, and linked the presence of mental health issues to COVID-19 related stressors and sociodemographic factors [28]. Increased psychological distress among the college student population, and of particular severity in marginalized populations, were seen in similar studies and on a global scale [29,30,31].

Emergency Remote Teaching and Predominantly Undergraduate Institutions

It has been estimated that between 750,000 and a million faculty in the United States were required in some fashion to transition their courses to ERT, impacting over 10 million students [6]. Despite the widespread adoption of ERT, higher education in the United States is a complex landscape consisting of institutions with numerous structures, operations, and visions [32], and it can be expected that institutional differences, as well as their locations, would create uneven and unique challenges for them to fulfill their unique missions.

Predominantly Undergraduate Institutions (PUIs) are defined as public or private institutions that primarily emphasize undergraduate education over graduate and research programs. Through an analysis of institutional databases from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and Carnegie Foundation, Slocum and Scholl (2013) classified 2104 U.S. institutions as PUIs [33]. In contrast to doctoral granting institutions that conduct high levels of research (e.g., R1 and R2), PUIs award fewer doctoral degrees and faculty generally have less structured research responsibilities. The National Science Foundation (NSF; 2014) describes PUI grant eligibility as “accredited colleges or universities (including two-year community colleges) that award Associate’s degrees, Bachelor’s degrees, and/or Master’s degrees in NSF-supported fields, but have awarded 20 or fewer Ph.D./D.Sci. degrees in all NSF-supported fields during the combined previous two academic years” [34] (para. 5). However, despite less emphasis in research and doctoral education, many faculty at PUIs, especially in STEM disciplines, consider themselves to be teacher-scholars [35]. PUI faculty commonly integrate research within their teaching and involve undergraduate students in their research agendas [36,37], in addition to conducting scholarship on teaching and learning to guide their teaching through evidence-based pedagogy [38].

Given the teaching-focused nature of PUIs, faculty often have high teaching appointments [39,40], and a less flexible contractual workload compared to faculty at larger research-intensive institutions [41]. Student advising and university service is also a common expectation for PUI faculty [39]. In total, Bowne et al. (2011) reported that faculty in PUIs were expected to have more availability to undergraduate students and were exposed to a higher scrutiny of their teaching and pedagogy practices [42]. However, the close interaction between PUI faculty and undergraduate students has been perceived as a benefit to working at a PUI [40]. The emphasis in providing high quality undergraduate education that is led by pedagogical research and best practices has positioned PUIs to be leaders in shifting higher education from a teacher-centered practice toward a learner-centered practice [43,44].

Across higher education, there has been an increasing trend for undergraduates to be enrolled in distance education. In 2015, approximately 30% of all U.S. college students enrolled in at least one distance education course [11]. However, the growth of online education has been uneven, with smaller institutions having less of a proportion of their students taking courses online. The strong value small institutions hold toward a personalized and intimate learning environment led many of these institutions to become late adopters of distance education [45]. Clinefelter and Magada (2013) reported that the development of online programs was largely limited in institutions with 2500 students or less [46]. Less familiarity, infrastructure, and developed programmatic support with online instruction may have posed additional challenges for PUI faculty to transition to ERT.

2. Conceptual Framework

In this study, we investigated the impacts of COVID-19 on PUIs through the lens of teaching and learning, as teaching and learning are central to the mission of the PUI. Prior to our investigation, a holistic approach to conceptualize the factors influencing teaching and learning in higher education was used. Several theories guided our investigation as no one theory can fully describe the range of factors that influence teaching and learning, and, moreover, that can explicitly be used to examine the rapid and unprecedented change that higher education experienced in 2020 due to COVID-19. Toward this end, a wide array of educational research has attempted to conceptualize the range of influences and their outcomes on teaching and learning in higher education. Theories pertaining to student engagement [47], self-regulated learning [48], patterns of learning [49], and an integrated model of student learning [50] led our investigation. These theories provided an important lens to evaluate COVID-19′s impact on teaching and learning within PUIs and shed light on how COVID-19 may have affected PUIs differently compared to other types of institutions.

2.1. Student Engagement

Due to high levels of student engagement typical of PUIs, they are well positioned to advance student learning and professional development when considering Astin’s (1984) Theory of Student Involvement [47]. According to Astin (1984), “the amount of student learning and personal development associated with any educational program is directly proportional to the quality and quantity of student involvement in that program” [47] (p. 519). The theory, which embraces principles ranging from classical learning theory to psychoanalysis, further describes how the effectiveness of educational policy or practice is positively correlated to the capacity to improve student involvement.

Astin (1984) reported that the place of student residence impacts student learning and personal development. For example, Astin (1984) suggested that living on campus promotes student engagement, and has been shown to improve students’ artistic interests, liberalism, interpersonal self-esteem, success in extracurricular activities, satisfaction with the undergraduate experience, and even strengthens faculty–student relationships [47]. In fact, Astin (1984) reported that frequent interaction with faculty is the strongest predictor of student satisfaction in college, and an increase in faculty–student interaction improves students’ satisfaction with all aspects of their institutional experience. As previously described, PUIs favor strong relationships between undergraduate students and faculty members [40,42]. The displacement of students from their residential dormitories at the onset of COVID-19 [7], and the resulting transition to ERT may have threatened the typical high levels of interaction between PUI faculty and students, thereby impacting student engagement, experience, and performance.

Research on the influence of student engagement in teaching and learning within higher education has evolved since Astin’s (1984) Theory of Student Involvement. In a review of student engagement research in higher education, Kahu (2013) described four dominant research perspectives on student engagement: (1) behavioral; (2) psychological; (3) socio-cultural; and (4) holistic [51]. Although each of these perspectives view student engagement through a different lens, there is clear evidence that student engagement is a critical factor in teaching and learning. Of most interest to our study, the behavioral perspective describes how institutional and teaching practice relate to student satisfaction and achievement. For example, institutional practices, such as providing necessary support services [52], and practices that emphasize active and collaborative learning improve student engagement [53].

Kahu (2013) proposed a conceptual framework that combined the four dominant perspectives on student engagement through a wider socio-cultural context [51]. Within this framework, structural influences were categorized through both university and student factors. Of particular interest to our research was the student factor of lifeload. According to Kahu (2013), lifeload is “the sum of all the pressures a student has in their life… [and it] is a critical factor influencing student engagement” [51] (p. 766). A student’s lifeload can be increased due to employment demands, needs of dependents, financial stress, and health concerns [54]. As noted by Kahu (2013), these factors exert influence during times of crisis [51]. We expected that the COVID-19 crisis increased students’ lifeload and thereby had a prominent impact on student engagement during ERT.

2.2. Self-Regulated Learning

Research on Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) suggests that students who are more adept to set goals and plan for learning, and who consistently monitor and regulate their motivation and study habits, are more likely to achieve academic success compared to their peers [48]. Pintrich and Zusho (2007) proposed a model of student motivation and self-regulated learning in the college classroom [48]. In the model, personal characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity) and classroom context (academic tasks, reward structures, instructional methods, and instruction behavior) influence students’ motivational processes and self-regulatory processes. Motivational processes are illustrated by students’ control beliefs, values, and emotions, whereas self-regulatory processes include the regulating context and are demonstrated by students’ ability to regulate their cognition, motivation, and behavior. Outcomes of the model include students’ choice, effort, persistence, and achievement in the college classroom.

As higher education moved to a remote learning format, students were undoubtedly placed in a more autonomous learning environment, which requires more self-regulation of their cognition, motivation, and study habits [50]. Rapanta et al. (2020) suggested that faculty will need to be cognizant of the time and effort that students will need to regulate themselves during the abrupt transition from face-to-face to remote learning [20].

2.3. Patterns of Learning

Vermunt and Donche (2017) summarized research on student learning patterns in higher education and described a learning pattern as “a coordinating concept, in which the interrelationships between cognitive, affective, and regulative learning activities, beliefs about learning, and learning motivations are united” [49] (p. 270). Research on patterns of learning were influenced by SRL (e.g., [48]) and Student Approaches to Learning (SAL) (e.g., [55]). Personal factors, contextual factors, and learning patterns affect learning outcomes. Research has suggested four patterns in which students learn: (1) reproduction-directed (e.g., memorizing material for a test); (2) meaning-directed (e.g., understanding the meaning of what is being learned); (3) application-directed (e.g., connecting relationships between what students learn with the outside world); and (4) undirected.

Undirected learning occurs when students do not know how to approach learning [49]. Undirected learning accounts for students’ poor self-regulation and leads to doubting their ability to cope with the new learning environment, as well as close reliance on peers and their teachers. Prior research has illustrated students can become undirected learners when there is a transition from one form of schooling to another, such as students coming from another country where pedagogical practices are different, and when students transition from high school to college [56].

Faculty at PUIs generally emphasize learner-centered instructional approaches that require students to take control of their own learning over teacher-centered approaches (e.g., direct instruction). Vermunt and Donch (2017) suggested that, over time, students begin to adopt learning patterns that are best aligned to the teaching approaches used [49]. As a result, it could be assumed that students attending PUIs may have become more accustomed to learning through meaning-directed patterns, as opposed to reproduction-directed learning that could be more appropriate in teacher-directed approaches (e.g., direct instruction). Faculty’s change of instructional approaches seen in ERT [6] may have caused students to experience disruption in the learning pattern they have been accustomed to, and, therefore, could catalyze the presence of undirected learning.

2.4. Integrated Model of Student Learning in the College Classroom

The Integrated Model of Student Learning in the College Classroom, proposed by Zusho (2017), effectively employs the strengths of the common student engagement theories previously described (e.g., student involvement theory; [47], SRL, [48]; and patterns of learning [55,57]), and organizes these theories within the context of higher education. The Integrated Model of Student Learning in the College Classroom was particularly useful to guide our research on COVID-19 and college teaching because it not only applied existing student engagement theories to college learning but illustrated the many other variables and their relationships that have influence on student learning outcomes. For example, the model displays the complex and interactive relationships between college students’ cognition processes, motivational processes, and contextual and personal factors, including individual characteristics (e.g., age, ethnicity), personality, prior knowledge, and beliefs about learning [50]. Additionally, the model includes the impact of students’ lifeload (e.g., Kahn (2013), [51]) on the learning process. The learner variables identified in this model, both independently and collectively, served as a frame of reference and lens to study the complex landscape of college learning, and the added complexity of teaching during a pandemic.

Although the Integrated Model of Student Learning in the College Classroom conceptualizes student learning and learning outcomes, the model also served as a useful reference to view variables from a teaching perspective. For example, included in the model is instructional methods and behaviors, curriculum, institutional support, academic tasks, academic discipline, and instructional planning, monitoring, and evaluation. As illustrated in the model, these teaching-based variables have direct influence on student learning. The investigation of these variables from the teaching perspective (e.g., selection of a teaching methods during ERT) is of obvious importance to understand the implications of COVID-19 on the teaching and learning process in higher education.

3. Purpose

The purpose of this research was to investigate how COVID-19, and the corresponding abrupt transition to ERT during mid-to-late March of 2020, impacted the teaching and learning process. Due to the wide range of institutional contexts in the U.S. higher educational system, we narrowed our approach to focus on PUIs located in the Midwest, United States. Furthermore, we sought to understand the impacts of COVID-19 and ERT through the lived experiences of science faculty teaching at midwestern PUIs. Through documenting and understanding the challenges that faculty and students experienced, we aimed to provide recommendations to best facilitate ERT at PUIs in the event of future crises. Two overarching questions guided our investigation:

- What challenges did PUI faculty experience during ERT?

- What challenges did PUI faculty perceive their students to have during the same period?

4. Materials and Methods

This study was part of a larger project that employed an explanatory sequential mixed method research design. Explanatory sequential mixed method research includes two phases [58]. In the first phase, quantitative data is collected and analyzed. Following the quantitative phase, a second phase of data collection uses qualitative methods. The qualitative phase offers additional explanation to the results seen in the quantitative phase. Although the research participants in this study were involved in both phases of the larger project, the data and results presented in this paper were collected and analyzed in phase two, the qualitative phase, of our larger study.

4.1. Phase One—Quantitative

In the first phase of our research, we identified science faculty who taught predominantly at PUIs located in the Midwest, United States, as our research population for the larger project. A list of PUIs located in the Midwest was generated from an existing report on PUIs in the United States [33]. A sampling frame of faculty teaching biology or biology-related disciplines, and their email contact, was created through an extensive internet search. We used this sampling frame and organizational listservs (e.g., Society for the Advancement of Biology Education Research; Partnership for Undergraduate Life Science Education) to send participation requests for the first phase of the larger project.

Phase one, the quantitative phase, included a digital survey sent via Qualtrics to our sampling frame and to the listservs we identified. The survey was administered in late April and early May of 2020, several weeks after most U.S. institutions transitioned to ERT [5]. Our survey included a modified instrument that measured instructors’ use of scientific teaching practices [59], and compared instructors’ use of science teaching practices in the same course retrospectively prior to and during ERT. An instrument measuring instructors’ comfort with technology was also included on the survey, as well as questions related to instructor demographics and their institutional characteristics. The last question on the survey asked respondents if they would be willing to complete phase two of our study, which included their participation in an incentivized ($50), one-on-one interview following-up on their experience with ERT. This research was approved by Doane University’s Institutional Review Board.

4.2. Phase Two—Qualitative

One-hundred and thirty-one respondents completed the quantitative phase of our study. Of those respondents, 59 indicated willingness to participate in phase two, a follow-up, one-on-one interview. Of the 59 individuals willing to participate in the qualitative phase of the study, we purposely selected 14 participants. The 14 participants were selected based upon having diverse characteristics on their implementation of scientific teaching practices prior to and during ERT, organized via a cluster analysis [60]. The 14 participants were also selected to have varying academic positions (e.g., assistant professor, associate professor, professor), years of experience teaching undergraduate STEM, prior experience teaching remotely, and used varying modality types (e.g., synchronous, asynchronous, blended) during ERT. See Table 1 for characteristics of our 14 participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of interview participants.

4.3. Data Collection

Due to the potential sensitivity of the topic, anticipated variation of experiences, and exploratory nature of this research, one-on-one interviews were selected for data collection over other means such as focus groups. A semi-structured interview guide was created and deemed most appropriate to elicit thick and rich data [61], while providing the flexibility necessary to probe and validate the meaning of responses [62]. The semi-structured interview guide contained three major sections: (1) changes in faculty scientific teaching practices as a result of ERT; (2) faculty and student challenges related to ERT; and (3) faculty support related to ERT. The interviews were conducted via telephone for ease due to COVID-19 and proximity restrictions. However, as described by Cachia and Millward (2011) [63], telephone interviews are appropriate and effective for administering semi-structured interviews. The completeness, credibility, and accuracy of participant responses were achieved through the moderator’s use of member-checking strategies [64]. The interviews were conducted in June of 2020 after the conclusion of the semester. Interviews were conducted by a trained moderator and interview lengths ranged from 36 min to slightly over two hours, with an average length of one-hour and 22 min.

4.4. Coding and Theme Development

An initial codebook was developed and guided by our semi-structured interview guide, by an initial theme analysis from the larger project, from existing literature, and from the researchers’ own observations regarding the abrupt transition from in-person to remote teaching. The codebook was discussed and created by the three researchers who coded the transcriptions. After several iterations, the final codebook contained 14 codes and 24 sub codes. The three coders had prior experience in qualitative educational research. One coder held a doctorate in Urban Education, Adult, Continuing, and Higher Education Leadership and was the Director of Institutional Effectiveness at a PUI. The second coder held a doctorate in Agricultural Education with a focus in teaching and learning in agricultural/environmental sciences and inquiry-based instruction and was an Assistant Professor of Environmental Science at a PUI. The third coder conducted the interviews for this study and was employed as a project manager at the Bureau of Sociological Research at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and held experience in qualitative methods.

The researchers used the established codebook to code 20% of the interview transcripts. Three coding trials were conducted, and after each coding trial the researchers discussed discrepancies between coding results. After the third trial, intercoder reliability was achieved. Intercoder reliability was accessed by Krippendorff’s alpha, a reliability estimate used in subjective judgements [65]. Final intercoder reliability was established at 0.84, and was deemed highly reliable. The 11 remaining interview transcripts were divided among the three researchers to complete coding. Lastly, the coded data were analyzed to determine emergent themes.

5. Results

The PUI faculty in this study experienced a wide-range of challenges during ERT at the onset of COVID-19. Four overarching themes were identified that can be used to describe the most encompassing challenges our faculty experienced during ERT. Additionally, five themes were found that can be used to describe the most encompassing challenges that students faced during ERT.

5.1. Challenges Related to Teaching

5.1.1. Pedagogical Changes

Nearly all faculty described their most significant challenge with ERT as the speed in which the transition to ERT had to occur, and the accompanying pedagogical changes required of ERT. The abrupt change from face-to-face instruction to ERT occurred in a matter of days. Although some PUIs gave faculty additional time to prepare for remote instruction (e.g., a week), the enormous tasks of learning new pedagogical approaches, identifying and incorporating new technologies, and changing academic content to fit a revised calendar, and appropriate for ERT, was difficult for most faculty. Adding to the complexity, was the rapid pace in which these changes had to occur and the many underlying uncertainties the pandemic caused.

The rapid transition to ERT caught most faculty by surprise. Participant 5 described the experience as “sticker shock,” as he recalled first learning that his institution was going to remote instruction, “Your set on one mode of teaching and delivery, and then all of a sudden need to go to another one… [at my institution] we were told on a Friday that from the following Monday, everything was going online.” For Participant 10, the decision to transition to remote instruction was made over her spring break. To make matters more complicated, during her spring break she was leading a field course out of state with students. She explained her conundrum, “Now I get to figure out how to [move courses to a remote format] in one week and try to transition multiple courses that have never been online to an online modality.” She continued by saying, “I wasn’t even in a position where I could go to a computer and sit down [and] start working on anything.” Participant 4 was also on spring break when his institution announced they were going fully remote the week after, “I was on vacation, so I wasn’t in a place where I could do any work and they actually ended up extending spring break for another week for students.” He explained that although he felt grateful for the extended week to prepare, he still felt under pressure, “I ended up having one week then really to rush and get something put together…so [I was] a little bit panicked.”

A few of the PUI faculty members we interviewed were already well versed with online instruction or already used online components in their existing courses, and this appeared to have helped them prepare for and teach remotely. However, a majority did not have prior remote teaching experience nor were familiar with pedagogy for online teaching. Participant 2, who had no prior experience teaching remotely, described her struggle, “I just had to [transition to remote instruction] with hardly any research and planning and just not knowing if what I was doing was even the right thing to do.” Participant 2 continued by explaining how this experience varied from her typical course redesigns, “Normally, I would only redesign one class a time and instead I was redesigning five classes at a time without having any idea if the things I was doing were going to work or were reasonable.” Participant 4, who also had never taught remotely before, shared a similar sentiment, “Remote teaching can be a very effective tool if you know what you’re doing and if you’re doing it correctly. …I’d never done it before and I didn’t necessarily know the correct way of doing it.” Participant 1, who was also new to remote instruction, summarized her experience, “I found [transitioning to ERT] to be a new challenge to learn new ways to present my material.” She continued by saying, “I felt like I was busier and spending a lot more time on my classes when we went online versus when we were face-to-face because I was creating a lot more content for my students.”

Most faculty explained that they had to redesign teaching activities and content to make remote instruction work. Participant 6 described his experience transitioning his coursework to remote instruction,

So I would look at what I had planned and I would ask myself okay, how can we do this virtually? And I’d say about a third of the time, we could pretty much do it the same way we might’ve done it in the classroom, and a third of the time it could be modified and a third of the time it was just a no go.

Some faculty mentioned creating new assignments that were appropriate for an online format. Participant 13 described challenges creating new assessments, “I just [needed] to come up with some form of assessment that would not easily be cheated on [in the remote format]…so you know, there were lots of challenges.” Like several other faculty, Participant 14 decided to cut down the amount of content taught, but his main concern was the elimination or reduction of lab practices. He explained, “It’s really the laboratory, the hands-on application component to it that I think suffered [as a result of remote instruction].” He continued by describing his concern requiring students to complete hands-on learning activities remotely, “It’s the inability to standardize what students have available to them…so it is that inequity, that extreme variability in what students have available to them is one of the things that makes it very difficult.”

Several faculty members mentioned being surprised by the amount of time required to prepare and modify course materials for the remote format. Participant 6 stated, “So I ended up spending a lot more time than I had thought I would trying to modify things,” and Participant 14 added “time-wise every step of the way is taking more time than it had previously.” However, not all teachers felt the same way. For example, Participant 4, who shared, “It was easier to get stuff prepared than I thought because I had so much less interaction with students, I actually had more time.”

Although there was a mixed sentiment on what components of ERT required the most time, nearly all faculty described time management to be a significant challenge. A majority of faculty mentioned that there was a dramatic increase in the time spent emailing students, as Participant 6 expressed, “Trying to respond to the kids remotely versus in real time just took a lot more time and they had bigger needs.” Participant 3 who described herself as “an hour ahead of the students most of the time and always behind on grading”, added that time management was a challenge for her, specifically “always trying to get back to students in a timely manner.” Participant 10 summarized her thoughts on time management by saying, “I spent an inordinate amount of time answering student emails throughout the week.”

5.1.2. Work-Life Balance

As universities sent students home and operated remotely, most faculty were strongly urged, if not required, to work from home. Faculty who had families found themselves sharing their new work environment with their spouse and kids. A majority of faculty described difficulties working with kids in the home. Participant 6 described his experience, “The biggest challenges that I expected to see and that I actually saw involved the personal switch of not being in an office for eight hours a day, but instead of being at home with two small children.” Participant 2 echoed the sentiment,

All of a sudden you know, I was maybe 10 or 15 min before someone, like a child would come in and bug me for something or need something you know, I just didn’t have the physical brain power to spend on [work] like I would have liked.

Participant 10 further expressed challenges teaching from home with small children, “The kid was home and she was running around making noise and it was hard…you know, go do something and leave me alone for some chunk of time.” Additionally, like what several other faculty mentioned, she described new spousal conflicts from the shared work-home environment, “[My husband] doesn’t do work from home. So when he’s home, he has nothing else to do. And when I’m home, I have to work and that caused friction and issues.” The shared spousal workspace was an issue for Participant 3 as well, “[My husband and I] felt like we were working all the time and it was really difficult to separate.” For Participant 10 the biggest challenge was separating work from family time despite being at home. She elaborated on her thoughts,

I have a family. I like to work really hard when I’m at work and then when I get home I don’t like to be on my laptop a lot or answering a bunch of emails or doing a bunch of grading unless I absolutely [have to]. …It took maybe a good few weeks to a month to kind of get into the mode of [doing] work at home…that was hard.

A few teachers described positives from working from home and forming stronger bonds with their family. Participant 9 stated, “I actually like working from home a lot better. I have little kids so it helps me be more involved with my family, I get to eat my meals with them, so I’ve actually enjoyed it.” Several participants also mentioned spousal support, like Participant 3, “My husband also teaches and his school obviously went to remote learning. I’ve always been very lucky to have somebody else in the house who understands what I’m doing and can support me both emotionally and… bounce [off] ideas.”

5.1.3. Face-to-Face Interactions

A strong majority of faculty described negative impacts stemming from the loss of a face-to-face learning community. The close-knit learning community and strong interactions between faculty members and their students typical of PUIs appeared to degrade during remote instruction. Several faculty members described a loss in colleague support as a major challenge, as described by Participant 2,

Normally…I might go talk to my colleague down the hall who maybe has done this before, or might have some sort of experience with it…and suddenly…I was on my own, without the sort of support that I might normally be able to rely on.

However, overwhelmingly, faculty members described the loss of face-to-face interaction with students as the largest negative impact. Participant 5 described his experience,

[The biggest challenge for me] was I lost my connection with the students. I lost my touch. Absolutely. And so one of the reasons I teach in an institution which has a really low student to teacher ratio like we do is because I like the interaction with the students, getting to know them on a personal basis, a very personal basis. …I’m not sure how I’m going to overcome that [next] semester [if we continue remote].

Participant 8 shared a similar experience, “I think the hardest part for me wasn’t the actual teaching online. It was not seeing my kids, my students.” Participants 3 echoed the sentiment, “I like being in the classroom, I like being able to talk to students. You know, the interaction and being able to provide hands-on opportunities.” Participant 12 summarized the overarching feeling, “A big part of my personality as a teacher is the face-to-face community, building the peer learning. I foster the positive interdependence I build in the classroom.” Although most faculty expressed that the loss of the face-to-face learning community negatively impacted their ability to build student rapport, Participant 1, who described herself as “introverted”, expressed that remote instruction allowed her to be “more personalized online [and] helped [her] make connections with students.”

Several faculty members mentioned that the loss of face-to-face teaching reduced visual feedback cues that guided their teaching behavior. For example, Participant 3 stated, “when I couldn’t see them face-to-face [I didn’t] have any visual cues as to whether I was getting through [to students]” and Participant 5 remarked, “I was not able to look at [students] face-to-face and gauge their reaction.”

The abrupt change into a remote teaching environment caused some faculty to question their teaching performance. Approximately half of the faculty directly stated that their teaching performance decreased during remote teaching. Participant 4 said, “So my thoughts personally are I think it decreased [my] teaching performance,” and Participant 14 remarked, “I doubt that I was effective.” Participant 13 described his teaching performance as being “negatively” impacted as he described what the remote learning environment felt like to him, “I can’t be there to explain things and make the jokes that I would, and, you know, sort of engage the students. So my teaching performance is more delegated to kind of, to feel like an online tutor.”

Some faculty described a benefit to their teaching performance in the long run. Despite the abrupt transition to remote instruction being difficult and a “learning curve” (Participant 14) for most, faculty were able to learn new teaching strategies, incorporate new technologies, and to “reflect on what [teaching] content really matters” (Participant 7). Participants 1 and 14 summarized the attitude of many faculty well by saying, “Yes, I had to learn some new skills, but you know that’s a good thing,” (Participant 1) and “There were some good things that came of [this experience] that I can use and carry forward” (Participant 14).

The loss of the interactive, face-to-face learning community caused faculty to experience a significant decrease in career satisfaction. Nearly every faculty member overwhelmingly stated they were less satisfied with their work. Participant 12 described what this experience meant to her and to her career satisfaction,

The challenges of not interacting with students on a daily basis has greatly decreased my satisfaction with teaching. I got into this and I am at a small private college because the interaction with the students and the community that we build in the classroom is very important to me and so not getting to see students regularly, not having them in my office asking questions, not having the rapport with them, has really made it feel like I’m interacting with a computer and it’s very hard [for me] to find that rewarding.

Participant 2 described her experience and beliefs toward her career satisfaction,

I didn’t get the pleasurable part of [teaching], which is seeing the students, talking to the students, you know, when they get that little light bulb that goes off over their heads and they like understand something, like I never got any of those rewards. I just felt like it was a lot of the part that I don’t like and none of the rewards that I do like.

5.1.4. Physical and Mental Health

Some faculty experienced health-related challenges caused by the impacts of COVID-19. As faculty began teaching remotely from a computer, moving and walking during the workday decreased, contributing to physical ailments. Participant 1 described her experience,

When you teach face-to-face classes you go into a classroom, you’re up and on your feet and you walk around the classroom. I didn’t have that time every day, I was sitting on my computer working…it’s not good for my body so I don’t feel the best.

Participant 3 added “sitting in front of the computer all the time ended up with my neck and shoulders and mouse hand hurting by the time I went to bed every night.” Participant 2 described her physical ailments as an “intense pressure on [her] chest all the time” and feeling “overwhelmed constantly” leading to higher blood pressure and lowered ability to sleep.

Despite only a few teachers specifically mentioning physical health issues and none mentioning being physically sick from the virus themselves, nearly every participant discussed mental health challenges related to increased stress and anxiety. According to Participant 13, the experience was “more stressful than [he] thought [it would be].” Participant 10 added “It’s extremely stressful. Like the whole thing is stressful.” Participant 5 said, although he does not tend to get stressed out much, his well-being “has actually taken a hit” because he was “stressing out a lot more.”

When asked about the specific cause of the increased stress and anxiety, several faculty members described uncertainties related to the pandemic. Participant 10 contributed,

I mean, and just the plain old, ongoing anxiety of being in the middle of a pandemic and you are shut at home, [sic] cause the, the whole place is essentially under a near quarantine. I mean, that’s daily, ongoing anxiety is a real issue and that interferes with your ability to focus and concentrate and think and do work.

To Participant 11, it was the “stress of just sort of the unknown and the virus.” Participant 14 described accepting the uncertainty to deal with the stress, “So yeah I think you know from a mental perspective there were a lot of unknowns and a lot of uncertainties but if you’re willing to accept a level of uncertainty then it wasn’t so taxing.”

A few faculty members related the increase in stress directly to changes in work structure and workload. Participant 6 said, “It was more hours worked per week and it did get stressful at times because I’m also holding down two, we’re only supposed to have one, but I’m holding down two service positions.” Participant 2 described how the abrupt change in work structure impacted her,

It was just all of a sudden everything changed and it was just my work life that changed, but it was also my personal life that changed and it just felt like you know, everything coming so fast. Especially in the month of March everything was changing so fast…like trying to teach classes somehow this way that it, it just, it just felt awful. …You know, like I just felt overwhelmed constantly.

Other factors leading to increased stress levels were from a “lack of good communication from administration” (Participant 3) and not being “able to interact with students anymore” (Participant 4). Participant 2 described her stress being relieved toward the end of the semester, “It really wasn’t until maybe like there was two weeks left in the semester where I was like okay, I feel I can finally breathe.”

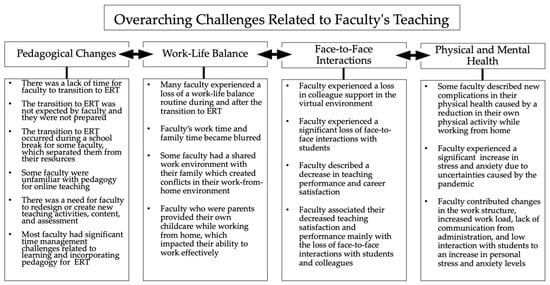

5.1.5. Summary of Challenges Related to Faculty’s Teaching

Key findings related to the themes of pedagogical changes, work–life balance, face-to-face interactions, and physical and mental health are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PUI faculty’s identified challenges related to themselves and their teaching during the onset of COVID-19 and ERT.

5.2. Challenges Related to Learning

5.2.1. Learning Patterns

According to faculty, students faced a multitude of challenges as a result of the swift change from face-to-face learning to remote learning. However, faculty were split on the severity of these challenges. Some faculty explained that many students just were not in the mindset to take courses remotely, and this had a negative impact on their success in the remote settings. Participant 5 shared, “Students had a tough time. Now, let me rephrase it, some did well, some didn’t do well, but on average students had a tough time.” Participant 5 continued to describe how his students were not prepared nor did not favor online instruction, and summarized by saying, “[Students] signed up for a face-to-face class for a reason.” Participant 6 elaborated, “I didn’t realize how much kids were just logging in and zoning out…until the final exam results came in.” He then added, “[Students] just need that supervision [typical in face-to-face formats] to stay on top of things and when they’re left to their own devices, it falls apart and they’re not self-disciplined to stay on top of it.” Some faculty attributed this to typical PUI characteristics, as Participant 4 alluded to,

I also was of the opinion going into this that the students really were going to struggle with it because the nature of the school it was, you know, [a] small school and so they’re used to getting a lot of contact and a lot of interaction with their faculty and instructors and now all of sudden that was going to change and go away

In addition to faculty being concerned about their own time management, they also acknowledged that their students struggled with time management and organization stemming from the abrupt course modality change. “Time management was a huge challenge” for Participant 7’s students. He continued be saying,

[Students] would complain about the bombardment of emails. So like you know a faculty member emailing them and saying do this. And then 10 min later say, no, actually do it this way. And then an hour later say, no, do it this way. They had a really hard time with scheduling and keeping track.

Participant 3 described her students’ experience similarly, “time management was definitely something that students talked about…and all of a sudden getting just email after email after email from faculty whereas in the past… [they were hearing] announcements in the classroom.”

5.2.2. Technology Access

Nearly all faculty described students’ lack of access to technology as being one of the largest on-going challenges after transitioning to ERT. Participant 9 “did not expect to encounter [issues with student access]” and described “internet access [as] the problem.” In most cases, the transition to remote instruction required students to leave campus dormitories and to move back home, where access to the internet was limited or not available. Participant 2 described her perspective,

[Some students didn’t] have reliable internet at home and any place they might’ve gone to get reliable internet like the school or a coffee shop or you know, a library where you used to be able to count on getting reliable internet. Suddenly [students] couldn’t go to any of those places…it was a problem the entire semester because you know, the entire world was shut down or at least most places were shut down.

Faculty expressed that students moving home to rural areas had the most significant challenges related to technology access. Participant 10 described a student in her class, “I know I had at least one rural student that basically had no internet and she did have to essentially drive to the McDonald’s and sit in the parking lot to do anything.” Participant 12 mentioned a similar experience with “a student who had no internet access at home” and the student having “to travel to wherever she could pick up Wi-Fi.”

In addition to getting access to the internet, slow internet speed was an ongoing issue, especially for students whose instructor taught through a synchronous modality. Participant 14 described his experience using live video conferencing, “Students would come on, they would be on for a little while, they would get dropped, they would come back on. So, you know, maintaining a continuity with them [was difficult].” Participant 9 shared a similar experience with video conferencing and having students with poor internet connectivity,

They’re freezing or they’re cutting out, or it gives you a really, really big delay…and then hearing [and] speaking [issues], that’s really frustrating for that person, well, for everybody involved. You can’t possibly be getting anything out of a class if that keeps happening to you. I mean, why, why would you ever want to log into a class if that keeps happening to you because of bad connectivity?

Students’ unreliable internet was an issue for teachers using asynchronous formats as well. Poor internet connections led to issues with students submitting assignments and taking quizzes. Participant 10 summarized her experience,

I did have most [students] say they had their internet cut out on them when they were doing things. And I would go to look at where they were working on the quiz and I could see that it stopped after two minutes or something.

Although lack of reliable internet appeared to be the largest challenge related to students’ ability to access course material, nearly half of faculty members mentioned students’ lack of unrestricted access to a computer. For a few faculty members, their students were on spring break when the transition to remote instruction was announced, and thereby separating students from their resources. Participant 4 described her experience with this,

[Students] left their computer in the dorm when they went on spring break and then all of a sudden in the middle of spring break they were told they couldn’t come back. So that was a problem…it took [students] three weeks to be able to get their computers back from the dorms.

Participant 14 described some of his students being without computers and taking courses from their phones, which was not ideal. Another contributing factor for students’ lack of a computer or internet access was due to the technology being a shared resource in their family’s household. According to Participant 1, “[Students] had to figure out the best time of day for them to get online and do online stuff when internet speed was good for them because they were balancing the internet usage with the rest of their family.” Participant 2 shared a similar experience, “One student who you know had the one computer and there were essentially three people trying to learn on that one computer.”

Participant 14 summarized the issue by saying, “None of [the students] planned for this and so they didn’t have appropriate equipment or appropriate internet.” Despite these challenges, faculty described working with students to the best of their ability by “being flexible” (Participant 10) and encouraging “understanding and communication” (Participant 8). Some technology challenges were relieved by characteristics of their PUI. Participant 5 discussed his relief in that all of his students had access to computers through his university’s one-to-one program, “What really helped me, lucky, was that [students] all had an iPad, so no student couldn’t come back to me and say they did not have a device to use to complete the assignment or to work on it.” Participant 8 added that his university sent devices to students who did not have computer access. Although, he described challenges of that process,

There was a delay for those students getting things set up and there was a delay for our university to realize we have to put a device in these kids’ hands and you know so stuff like that was very, very frustrating for our students.

5.2.3. Additional Responsibilities

Several faculty members expressed that their students shared family-related challenges, especially for students who had kids of their own or who were looking after their younger siblings. Participant 1 explained her students’ situation, “Close to 25 percent of [my] students had families and working around and dealing with those two schedules while trying to find time to get their studies done [was difficult].” Participant 10 further explained the ongoing difficulties that her students, who were also parents, had, “If schools are out and your kids are home and you can’t afford daycare that is every day…and I know that’s the case probably for many of our students.” Participant 2 summarized the experience of her student who was also a parent,

I have one of my students you know, she was a mother of two. She had an eight-year-old and a six-year-old and they had one computer in their house and she was homeschooling you know, her eight-year-old, she was homeschooling her six-year-old. And then you know, she would be using that computer after the kids went to bed to do all of her assignments cause they only had one computer.

According to faculty, many students were also taking care of their younger siblings during the pandemic. Participant 12 expressed that her students “were helping provide childcare for younger siblings at home,” adding complexity to keeping up with class material. Participant 3 also recognized this challenge, “I didn’t know if [students] were going to be expected to be homeschooling their little brother or babysitting or what all.”

Some faculty also mentioned the frustration that their students experienced moving back into their family’s residence. Participant 7 described her students’ experiences,

I know my students struggled with living back at home. Some of them would struggle with their parents not recognizing that they were still technically in college and so they’d be asked to do stuff around that house all day when they were trying to get work done and it didn’t create the same kind of [learning] environment.

Participant 3 further described students’ struggles by saying, “You know [students] had been at least semi-independent adults living on campus and now they go home. I remember what that was like all of sudden you’re back under mom and dad’s rules…that’s awful.”

Over half of the faculty described challenges their students faced regarding jobs. A few faculty members mentioned that students’ job loss or job loss in the family impacted them directly. For example, Participant 7 described, “[My students] reached out directly and said you know, my dad lost his job and I’m picking up an extra shift to try and help out kind of thing and can I have an extension on this or that?” Participant 2 described a similar situation, “Maybe [a student’s] family member had lost their job so they needed to pick up you know, an extra job just to make ends meet.” Changes in students’ job schedules due to the pandemic also posed challenges. Participant 1 explained, “Some of [my students] got new jobs and some of their jobs changed their work schedule.” Participant 8 expressed concern with students juggling course work with new job demands, “[Students have] differing schedules or now they have to have a full-time job while they’re doing full-time coursework.”

5.2.4. Learning Community

Faculty overwhelmingly perceived their students to have experienced significant challenges transitioning from a face-to-face learning community to a remote one. Similar to how faculty expressed their own value toward a face-to-face learning community, they also believed their students valued the close-knit learning community typified by most PUIs. Participant 5 explained, “Many of the students that we have at [my PUI] come because they want personalized attention. They want the small classroom feel. They want to be able to interact with the instructor.” Participant 8 believed this to also be true of her PUI, “It’s like one big family…that’s the feel you get when you’re on our campus…and then what we did [when we went to remote instruction] was isolate [students] away from their college family so that was really hard.” Participant 4 shared a similar perception, “[My PUI] is a small school so [students are] really used to getting a lot of contact and a lot of interaction…with faculty members and instructors and all of sudden that [went] away.”

Students’ learning community was impacted beyond a reduction in faculty interaction. Participant 3 described how students left behind the “social lives and athletic events” they were used to. Participant 5 stated a similar opinion, “[Students] had plans for athletics, they had plans to do other things…missing their friends. So a lot of other factors come in [that impacted their remote education].” Participant 4 could tell that his students “were struggling with something socially,” perhaps due to their “social lives and athletic events being canceled” (Participant 14).

Faculty believed the loss of the face-to-face learning community caused a decrease in motivation, engagement, and performance for most students, but especially for students who were already struggling in face-to-face settings. Several faculty members mentioned that student participation was low during remote teaching and some students were completely absent. Participant 4 described his surprise by saying, “what I didn’t anticipate was how many students would really kind of start to drop off…in terms of their efforts, and in some cases I had students that really just disappeared,” and Participant 9 added that “student participation was probably the second worst problem” for him.

Faculty expressed that lower levels of student engagement, participation, and motivation were difficult to remediate through remote teaching. Participant 4 described his experience, “I don’t see [students] face-to-face…I can’t just say, ‘Hey, what’s going on?…some students would respond to my emails but there were a few that didn’t…so I even went to the phone and I started to call students.” Participant 13 portrayed a similar point of view regarding the online environment,

what it really comes down to [for students] is the motivation…to get things done. [Students] have to get things done when there isn’t anyone there to sort of check-in…to look [them] in the eye or to listen. [They] have to be self-motivated.

The lack of engagement in the remote setting compared to the face-to-face setting may have been challenging for students to stay motivated, as described by Participant 14, “We also had a certain amount of students that I think probably got frustrated with it or bored with it and you know didn’t show the discipline to it that’s required.”

When describing the impact of remote instruction on students’ performance, some faculty believed that student performance was negatively impacted, and others believed that performance was consistent from earlier in that semester. Participant 11 believed that student performance decreased, “I mean, overall I felt like the students were a little weaker this semester…but I don’t feel like I did as good a job at helping them learn what they needed to learn.” Several faculty members described a clear separation between top performing students, who consistently stayed engaged and had active participation during remote instruction, and students who struggled academically, who tended to lack motivation and self-discipline. Participant 10 described her experience,

Those 5 or 6 [students], they’re already getting an A, you know, they’re going to charge through it. They’re going to figure it out. They’re going to be fine…and there were several of them that I kind of pulled along. And then there were a couple of students that I barely heard from.

Some of the students who underperformed may have also experienced significant disruptions caused by COVID-19, such as home-life challenges, employment troubles, lack of consistent technology access, and mental health struggles, as these events were discussed throughout the faculty interviews. Lastly, faculty described their students to be mostly understanding, but not necessarily happy or extremely satisfied, about the abrupt transition to remote learning.

5.2.5. Stress and Anxiety

Faculty described stress and “generally anxiety as an ongoing experience” (Participant 7) for their students. Several faculty members had students reach out to them “mentioning they were struggling with something (mental health)” (Participant 4). According to Participant 3, “stress was probably one of the biggest things…for students”. She added that the stress was caused by students “trying to figure out what was going on when, when things were due, [and] what’s the timing.” The stress faculty’s students were having had a direct impact on faculty who deeply cared about their students’ health and classroom success. Participant 4 described his experience,

Some students [were] basically…like sorry, I haven’t done any work…I haven’t been able to do anything since this started. You know emotionally, it is like the emotional toll that they’re experiencing. Um, and that became a big problem for students and, and it was challenging for me because, I don’t know who was being affected by that and two I mean, I’m not, I’m just not trained on how to help someone in that situation.

The abrupt change from having a scheduled routine at school and a safe study space to moving and attending class from home contributed to some students’ stress, as described by Participant 12, “The upheaval in their lives you know the fear that all of us were experiencing…and an abrupt move home. [For] some [students] that might not have been a good situation to move home to.” In addition to the stress caused by a change in school structure, Participant 10 described student stress being caused by their worries about the potential health implications for themselves or family members contracting COVID-19, “So there’s students having all those other things going on [and] worrying about [themselves] getting sick or their, you know, grandparents getting sick.”

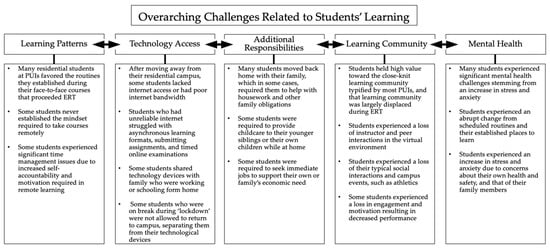

5.2.6. Summary of Challenges Related to Students’ Learning

Key findings related to the themes of learning patterns, technology access, additional responsibilities, learning community, and stress and anxiety are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

PUI faculty’s identified challenges related to students and their learning during the onset of COVID-19 and ERT.

6. Discussion

Although our study was not a comparative study between PUIs and other institution types, the PUI faculty in our study identified challenges that may have been exacerbated by typical characteristics of teaching and learning within PUIs. Faculty at PUIs generally have high teaching loads [39,40]. A majority of our participants described being overwhelmed with the workload required to transition and operate a large number of courses in ERT. Similar to findings by Johnson et al. (2020) [6], a majority of faculty in our study reported changing aspects of their courses to allow for ERT, including employing new teaching strategies, modifying assessments, and reducing course content. Prior research described that smaller institutions may lack the infrastructure and resources to support remote instruction [45,46]. Over half of our participants did not have prior experience teaching remotely, and some felt isolated in their efforts to transition to ERT. Similar to the prediction by Sahu (2020) [10], and findings from similar studies [22,23], a majority of faculty in our study, including faculty who previously taught remotely, reported feeling unprepared to transition to ERT due to a lack of training in online pedagogy and low comfort with the technology required of ERT. However, despite our participants’ initial low self-efficacy to employ ERT, most faculty described being able to successfully incorporate new technologies and pedagogy to an extent that got them and their students through the semester.

Rapanta et al. (2020) described that students’ accessibility to the learning environment would be a leading factor to contend with during ERT [20]. Faculty in our study confirmed this prediction. They described a proportion of their students not being able to access their course due to having no or limited internet access (e.g., low internet bandwidth), especially in rural areas. Additionally, faculty reported that technology access was hindered for some students due to resources (e.g., computer) being shared by siblings and other family members for remote school and work. Faculty also reported some of their students having to watch over siblings or taking on new job responsibilities. Faculty linked many of these occurrences due to their students’ family circumstances (e.g., family job loss, family members being essential workers, etc.). These findings demonstrate the compounded inequality between sociodemographic factors and access to education previously reported [19,24].

Previous research on the implications of COVID-19 illustrated the increased prevalence of college students’ psychological distress brought forth by the pandemic [25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. The faculty in our study acknowledged the anxiety and stress they believed their students to be experiencing. They described the cause of their students’ psychological distress as the general upheaval of their lives, fear of the unknown, changes in school structure and routine, physical isolation from peers and friends, and their ongoing concern for the safety of themselves and their family members. Faculty described students’ high level of anxiety and stress having negative impacts on student learning. Furthermore, a majority of faculty described an increase in their own stress and anxiety stemming mainly from technostress and techno-overload [21], but some faculty also contributed stress and anxiety from the inability to separate their work from new family responsibilities that emerged in the work-from-home environment.

Our findings illustrate an increase in what Kahu (2013) refers to as student lifeload, “the sum of all the pressures a student has in their life” [51] (p. 766). It is highly evident, based on our findings and those of similar studies, students’ lifeloads were increased due to instances including, but not limited to, new living situations, isolation, needs of dependence, changes in employment, financial difficulty, lack of technology access, changes in the learning environment, and a general increase in stress and anxiety. The factor of lifeload must be first acknowledged and understood when describing the impact of ERT on student involvement, engagement, and performance. Based on our interviews, and as suggested by Sahu (2020) [10], we found that a majority of PUI faculty in our study understood students’ unique situations during ERT and provided flexibility and support throughout the semester, although the degree of flexibility and support varied.

Faculty described a decrease in student engagement and performance in ERT compared to the traditional face-to-face setting. We previously described typical characteristics of PUIs, including close relationships and high levels of engagement between faculty and students [36,42], and a strong emphasis on active teaching [42,44]. It was apparent that the interaction between faculty and students was hindered during ERT. Even when teaching through synchronous or blended modalities (e.g., zoom), faculty described a loss in student engagement. This loss may have been catalyzed by faculty’s unfamiliarity with delivering and planning online instruction, and student’s unfamiliarity learning in this environment, especially given the vast difference between ERT and the highly interactive face-to-face environment that PUI students and faculty were accustomed to [40,42]. Like suggested by our faculty participants, Besser et al. (2020) found that students self-reported higher levels of disengagement and comparatively less learning during ERT [26].

When considering Vermunt and Donche’s (2017) Patterns of Learning [49], faculty acknowledged making significant, and necessary, changes to their teaching practices. In some cases, these changes likely disrupted the learning process students were accustomed to. Students who were unable to cope and adapt quickly to the new pedagogical approaches may have been more subjected to become undirected learners, and ultimately performing more poorly compared to their peers who were able to adapt to the new learning environment. Many faculty members described a clear divide among students who performed particularly well during ERT and students who performed poorly. Student factors that were identified as influential to performance aligned closely to those identified in SRL (students’ self-regulation of their cognition, motivation, and study habits; [48]). Rapanta et al. (2020) suggested that faculty needed to be aware of the time and efforts that students will require in ERT to regulate themselves [20]. However, few faculty in our study mentioned specific strategies they used to improve their students’ ability to self-regulate.

Many of our participants described missing the close interaction with their students. In a similar study, Watermeyer et al. (2021) reported that faculty believed their “pedagogical praxis had been reduced to the fulfilment of rudimentary technical function” [23] (p. 631). A majority of our respondents felt similarly, and most described their overall enjoyment and satisfaction with teaching as a career to be significantly reduced during ERT, and specifically due to a loss of student interaction.

7. Conclusions & Recommendations

The results of this research further demonstrate the significant impact that COVID-19 and the abrupt transition to ERT had on teaching and learning in higher education. Our qualitative investigation explored the lived experiences of 14 PUI faculty members during the onset of COVID-19. Each faculty member shared a unique, powerful, and reflective experience that captured this significant and historic disruption in postsecondary education. Despite the variations in experience, grand similarities were found for the largest and most overarching challenges. The themes identified in our investigation illustrated these wide-spread challenges, and these themes were described in the context of teaching and learning.

Our results concluded that faculty in our study were not prepared for ERT and had difficulty rapidly transitioning their courses to remote teaching. The transition to ERT required faculty to implement new pedagogical approaches and technologies, and to modify course content, which significantly increased faculty workload. Although faculty believed to have ultimately been successful at incorporating new technologies and delivering instruction in ERT, the success was deemed as minimal for most (e.g., just getting by). Inequalities in student access to the learning environment were compounded by the pandemic, where faculty cited that some students lacked physical access to the virtual learning environment due to technology barriers (e.g., device access; internet access) and demands from their new living environment (e.g., share responsibility to look over siblings; picking up new jobs). Faculty also experienced a change in their work–life balance, especially faculty who were parents to young children, who struggled meeting the demands of childcare with the increased workload. The lifeload of students appeared to be exhaustive, as faculty expressed significant concern about the mental health of their students—a crisis that has been echoed by recent literature. Faculty themselves wore thin and expressed higher levels of anxiety and stress, a general decrease in satisfaction toward their career, and lower teaching performance. There was clear displeasure in the lack of close interactions between faculty and their students during ERT, and many faculty members described the high level of student interactions as the primary reason they teach at a PUI.

The focus of this study was on the challenges that faculty experienced during ERT, yet we would not be diligent if we failed to report faculty’s embodiment of resilience and commitment to their students. Despite the high levels of initial stress and anxiety during the early stages of ERT, after several weeks of implementing ERT, faculty described being able to establish new routines, easing some levels of stress, and better navigating the demands of a new normal. There were few positives that were brought forth by the pandemic and ERT, but one of which, according to faculty, was being able to spend more time with immediate family and valuing that opportunity. After the conclusion of the first academic term in 2020, faculty described being better prepared for future instances of ERT. As predicted by Rapanta et al. (2020) [20], faculty in our study described learning new technologies and pedagogical practices that would be helpful in a post-digital era.