Implementation of a Thematic Analysis Method to Develop a Qualitative Model on the Authentic Foreign Language Learning Perspective: A Case Study in the University of Northern Cyprus

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Have real-world relevance and complexity.

- Provide opportunities to include different perspectives.

- Provide collaborative opportunities.

- Have integration across different subject areas and involve integrated assessment.

- Yield possible products and allow for competing answers or solutions.

1.1. The Implementation of the Efficient Learning Framework

- Convenient use of several information packages to access a wide range of English learning packages.

- The flexibility of handy gadgets that enables individuals to choose their learning environment.

- Cost-effectiveness features to save on outrageous expenses and manage them appropriately.

- Individuals can cooperate in group activities and play substantial roles.

- They are enabled to lead structural courses owing to their routine activities and updated resources.

- They have an assessment for the vast majority of scheduled plans.

- It is required to have a specific allowance for virtual learning environments.

- Accessible variations and how to use learning sources should be managed fundamentally.

- Timetable scheduling for learning and how to plan and personalize the experiences.

1.2. Principles

1.2.1. Real-World Relevance

1.2.2. Complexity and Ill-Definition

1.2.3. Provision of Opportunities to Include Different Perspectives

1.2.4. Provision of Collaboration Opportunities

1.2.5. Provision of Reflection Opportunities

1.2.6. Integration across Different Subject Areas

1.2.7. Integration with Assessment

1.2.8. Yielding Polished Products

1.2.9. Allowing Competing Solutions and Diverse Outcomes

1.2.10. Conducive Activities to Both Learning and Communicating

1.2.11. Motivation

2. Research Objectives

- What are your opinions about the mentioned principles of the learning of foreign languages and how they influence your daily routine activities?

- What is the importance of each principle based on your previous experiences regarding learning materials and tools?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of each principle?

- Which suggestions, amendments, and improvements do you think would be more appropriate for these principles?

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Method

3.2. Reliability

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mortazavi, M.; Hocanın, F.T.; Davarpanah, A. Application of Quantitative Computer-Based Analysis for Student’s Learning Tendency on the Efficient Utilization of Mobile Phones during Lecture Hours. Sustainbility 2020, 12, 8345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, N.; Numajiri, T. Global Englishes Language Teaching: Bottom-up Curriculum Implementation. TESOL Q. 2020, 54, 118–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abramova, I.E.; Shishmolina, E.P.; Ananyina, A.V. Advantages of authentic assessment over traditional assessment while teaching English to university students majoring in non-linguistic subjects. Samara J. Sci. 2018, 7, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, D.T. and Henry, G. Who teaches English learners? A study of the quality, experience, and credentials of teachers of English learners in a new immigrant destination. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 90, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baytak, A.; Tarman, B.; Ayas, C. Experiencing technology integration in education: Children’s perceptions. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2011, 3, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Gilakjani, A.P. A Review of the Literature on the Integration of Technology into the Learning and Teaching of English Language Skills. Int. J. Engl. Linguist. 2017, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ammon, U. David Graddol.English Next. Why global English may mean the end of ‘English as a Foreign Language. Lang. Probl. Lang. Plan. 2008, 32, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushioda, E. The Impact of Global English on Motivation to Learn Other Languages: Toward an Ideal Multilingual Self. Mod. Lang. J. 2017, 101, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, M.; Nasution, M.; Abdolahzadeh, F.; Behroozi, M.; Davarpanah, A. Sustainable Learning Environment by Mo-bile-Assisted Language Learning Methods on the Improvement of Productive and Receptive Foreign Language Skills: A Comparative Study for Asian Universities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymond, S.; Roche, B.; Bennett, M.P. Relational Frame Theory and Experimental Psychopathology; New Harbinger: Oakland, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wacewicz, S.; Zywiczynski, P.; Orzechowski, S. Visible movements of the orofacial area. Gesture 2016, 15, 250–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dediu, D.; Janssen, R.; Moisik, S. Language is not isolated from its wider environment: Vocal tract influences on the evolution of speech and language. Lang. Commun. 2017, 54, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, L.J. Effects of different language environments on Chinese graduate students’ perceptions of English writing and their writing performance. System 2017, 65, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.C. The crossroads of English language learners, task-based instruction, and 3D multi-user virtual learning in Second Life. Comput. Educ. 2016, 102, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilickaya, F. Authentic Materials and Culture Content in EFL Classrooms. I. TESL J. 2004, 38, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Canale, M.; Swain, M. Theoretical Bases of Communicative Approaches to Second Language Teaching and Testing. Appl. Linguist. 1980, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feez, S.; Quinn, F. Teaching the distinctive language of science: An integrated and scaffolded approach for pre-service teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 65, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guise, M.; Habib, M.; Thiessen, K.; Robbins, A. Continuum of co-teaching implementation: Moving from traditional student teaching to co-teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 66, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, H.; Larsen-Freeman, D. Teaching Language: From Grammar to Grammaring. TESOL Q. 2004, 38, 172–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmer, J. How to Teach English: An Introduction to the Practice of English Language Teaching; Pius Lan Tapi: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook, A. The Cultural Politics of English as an International Language. In Cultural Politics English International Language; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaravadivelu, B. TESOL Methods: Changing Tracks, Challenging Trends. TESOL Q. 2006, 40, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, W. Communication-oriented language teaching: Where are we now? Where do we go from here? Lang. Teach. 2014, 47, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, D. Communicative language teaching: Making it work. Elt J. 1987, 41, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, T. Design research from a technology perspective. Educ. Des. Res. 2006, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppisaari, I.; Herrington, J.; Vainio, L.; Im, Y. Authentic e-learning in a multicultural context: Virtual benchmarking cases from five countries. J. Interact. Learn. Res. 2013, 24, 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, N.; Wood, D. Facilitating creative problem solving in the entrepreneurship curriculum through authentic learning activities. In Activity Theory, Authentic Learning and Emerging Technologies; Towards a Transformative Higher Education Pedagogy; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ozverir, I.; Herrington, J.; Osam, U.V. Design principles for authentic learning of English as a foreign language. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 47, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al Shobaki, M.J.; Abu-Naser, S.S. The Role of the Practice of Excellence Strategies in Education to Achieve Sustainable Competitive Advantage to Institutions of Higher Education; DSpace at Alazhar University: Cairo, Egypt, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, S.; Pea, R. Designing a Blended, Middle School Computer Science Course for Deeper Learning: A Design-Based Research Approach; International Society of the Learning Sciences: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, S.J.; Jones, G. Teaching Computer Literacy with Transmedia Designed by Learners with Broken Window. In Learning Games; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, E.; Bell, P.; Brophy, S.; Hoadley, C.; His, S.; Joseph, D.; Orrill, C.; Puntambekar, S.; Sandoval, W.; Tabak, I. Design-Based Research: An Emerging Paradigm for Educational Inquiry. Educ. Res. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.-T. Design-Based Research: Redesign of an English Language Course Using a Flipped Classroom Approach. TESOL Q. 2017, 51, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Shattuck, J. Design-Based Research. Educ. Res. 2012, 41, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miles, M.A. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; SAGE: London, UK, 1994; pp. 50–72. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 10 | 55.5 |

| Female | 8 | 44.5 | |

| Age | 28–34 | 7 | 38.9 |

| 35–40 | 6 | 33.4 | |

| 41–45 | 5 | 27.7 | |

| University Position | Assistant Professor | 9 | 50 |

| Associate Professor | 6 | 33.4 | |

| Professor | 3 | 16.6 |

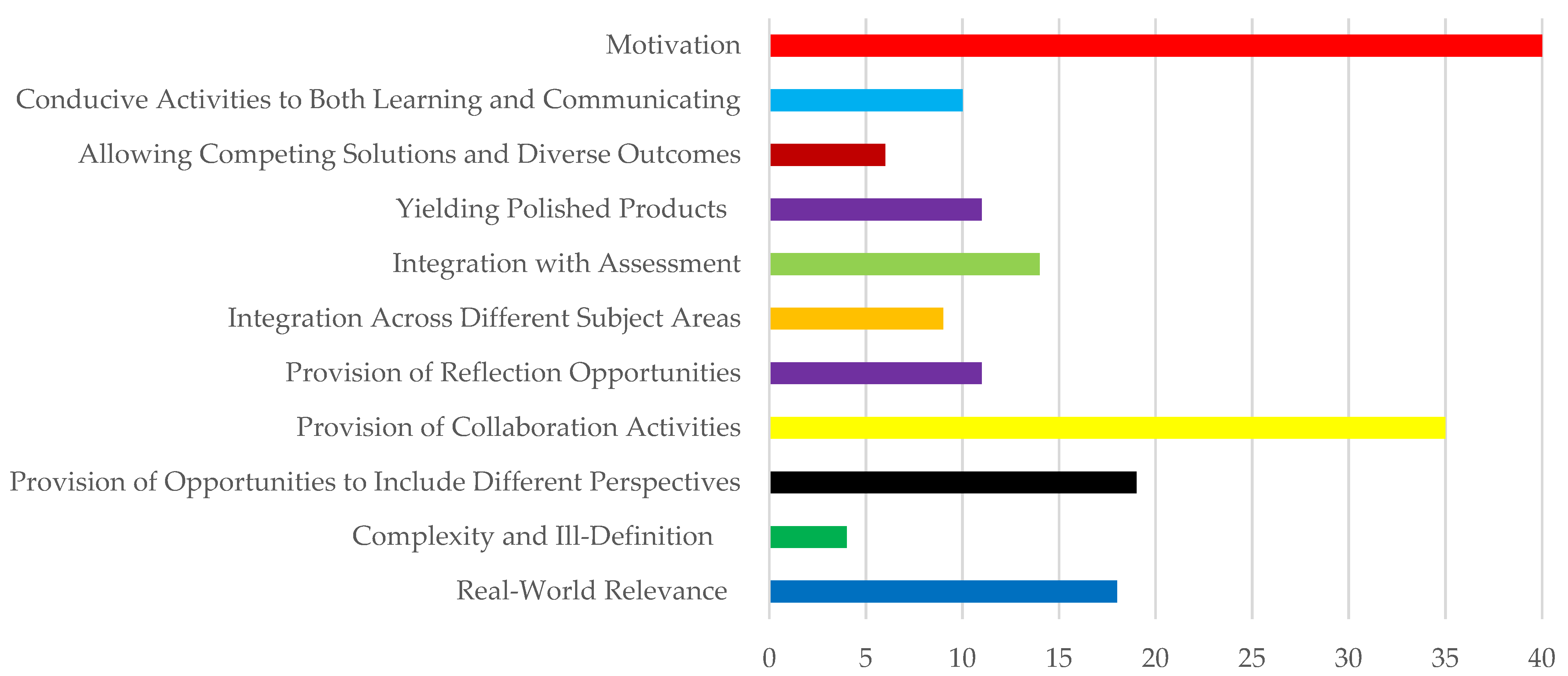

| Principles | n | % | Sampling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real-World Relevance | 18 | 10.11 | Real-world concepts as the main constituent in learning environments. |

| Complexity and Ill-Definition | 4 | 2.25 | The challenging nature of the task is to promote students’ skills. |

| Provision of Opportunities to Include Different Perspectives | 19 | 10.67 | To manipulate the task from different angles and share their knowledge and ideas. |

| Provision of Collaboration Opportunities | 35 | 19.66 | Joint problem solving is a critical feature in completing authentic tasks. |

| Provision of Reflection Opportunities | 11 | 6.18 | Set the ground for meaningful discussion, enhancing learning and experience. |

| Integration across Different Subject Areas | 10 | 5.62 | Points to the multidisciplinary nature of real-life tasks, requiring several skills to be accomplished. |

| Integration with Assessment | 14 | 7.87 | Successful completion of the tasks requires frequent assessment. |

| Yielding Polished Products | 11 | 6.18 | Creating a valuable product that was of use by itself. |

| Allowing Competing Solutions and Diverse Outcomes | 6 | 3.37 | They were given a chance to solve problems by reflecting on their repertoire. |

| Conducive Activities to Both Learning and Communicating | 10 | 5.62 | Authentic activities foster and enhance communication. |

| Motivation | 40 | 22.47 | Use various technological tools to perform the tasks appeared to be quite stimulating. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mortazavi, M.; Davarpanah, A. Implementation of a Thematic Analysis Method to Develop a Qualitative Model on the Authentic Foreign Language Learning Perspective: A Case Study in the University of Northern Cyprus. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 544. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090544

Mortazavi M, Davarpanah A. Implementation of a Thematic Analysis Method to Develop a Qualitative Model on the Authentic Foreign Language Learning Perspective: A Case Study in the University of Northern Cyprus. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(9):544. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090544

Chicago/Turabian StyleMortazavi, Mohsen, and Afshin Davarpanah. 2021. "Implementation of a Thematic Analysis Method to Develop a Qualitative Model on the Authentic Foreign Language Learning Perspective: A Case Study in the University of Northern Cyprus" Education Sciences 11, no. 9: 544. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090544

APA StyleMortazavi, M., & Davarpanah, A. (2021). Implementation of a Thematic Analysis Method to Develop a Qualitative Model on the Authentic Foreign Language Learning Perspective: A Case Study in the University of Northern Cyprus. Education Sciences, 11(9), 544. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090544