1. Introduction

Much effort has been spent on improving first year retention rates and introductory level courses under the assumption that students are more likely to drop out of college or their chosen majors early in their degree progress [

1]. Research historically and consistently indicates that thirty to fifty percent of all student withdrawals occur prior to their second year of college [

2,

3] and that first-semester GPA is a statistically linked to graduate rates [

1]. According to Maisto and Tammi [

4], student retention is important to colleges and universities since the pool of eligible college-aged students is decreasing and the cost of higher education is increasing [

5]. However, research has shown that individual and institutional characteristics may have an impact on student retention [

1,

4,

6,

7,

8].

Features that can affect college persistence and timing of attrition can be divided into pre-college and college factors. Pre-college factors can consist of attributes such as family income, religion, home-life characteristics, student demographics, parental demographics and education, and high school performance [

3,

6,

9,

10]. College variables for academic persistence can range from student community involvement such as living situation and involvement in campus life, to integration into the academic community that can consist of meeting with faculty, learning and balancing social skills, and dedicating an appropriate amount of time to coursework [

10,

11]. Both of these pre-college and college skillsets are critical to student success and students with under developed or lacking skills in either area can be at a higher risk for attrition [

7,

12]. A longitudinal study of first-generation college students showed that a specific focus on skill learning in their first-year lead to higher levels of achievement, however, this effect the impact of skill development was diminished as they moved closer to graduation, suggesting eventually, all students are developing skills throughout college [

13].

At-risk students comprise a broad category, with a single or multiple reasons why a given student might be considered at-risk, and graduation rates for at-risk students are low [

14,

15]. Students are considered academically at-risk at the University of Wyoming based on low high school GPA or ACT scores; this group of students represents larger amounts of minority, low-income, and first generation students than the general student body at the University of Wyoming [

10]. A study by Laskey and Hetzel [

16] shows that the pre-college factor of student personality was significantly linked to retention and academic success for at-risk students. With so many factors going into student success, it is important to remember that both student populations and colleges are always changing [

17].

For this population of conditionally admitted students at the University of Wyoming, an academic support program is available for them, called the Synergy Program. The Synergy Program enrolls approximately 144 students each year and offers first-year seminar courses as a requirement of conditional admission with either a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) or non-STEM (usually Humanities) theme. The majority of the Synergy students choose their seminar course based on personal interest.

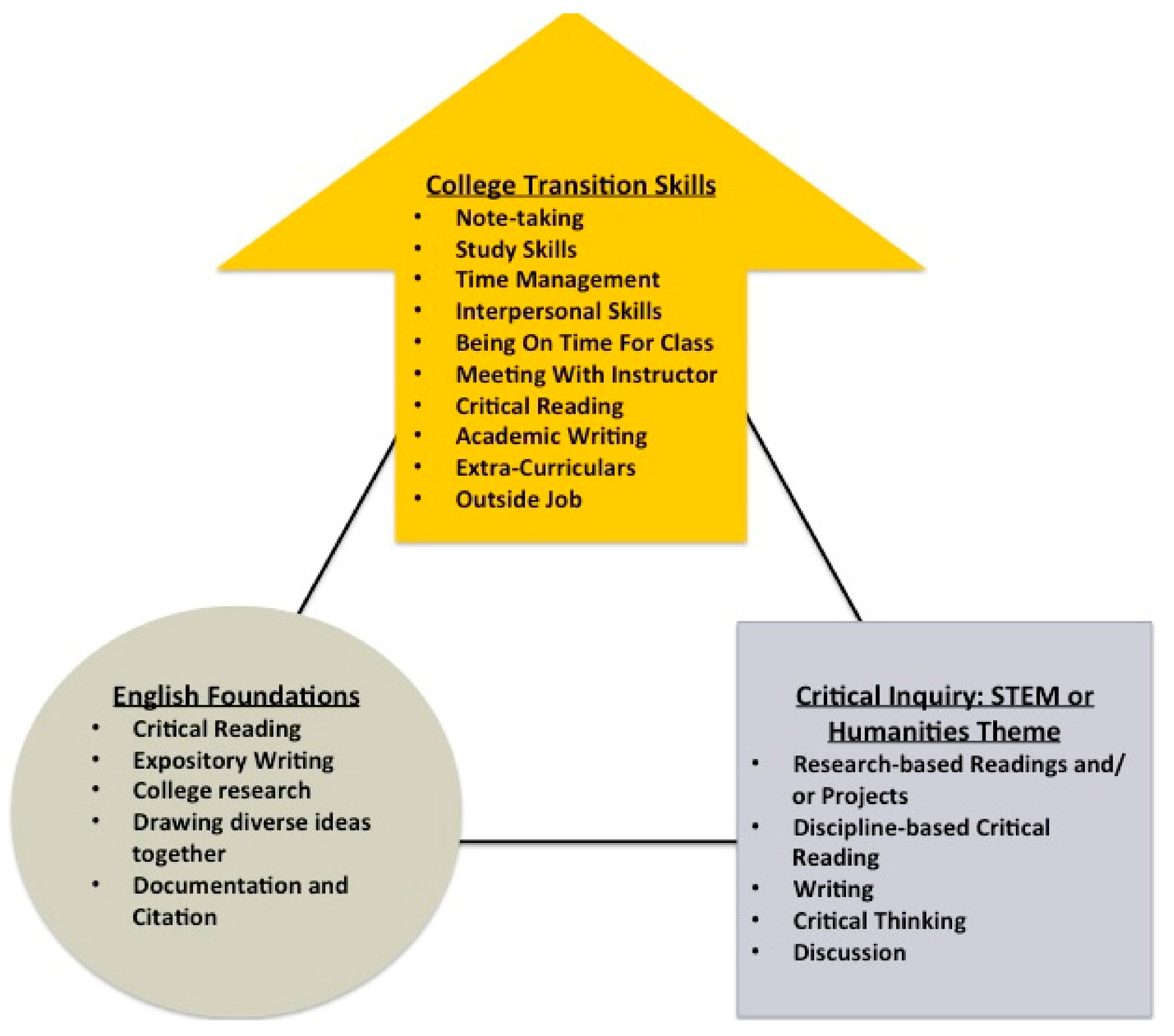

The Synergy Program at the University of Wyoming promotes academic success and retention for underprepared and at-risk students by creating a series of first semester curricula as theme-based college transition skills courses that are paired with English courses that focus on college level writing skills. This creates a cohort group of courses for the students with increased communication between instructors at the same time allowing greater development of student social networks (

Figure 1). Creating both academic and social networks by design helps to promote student engagement during the critical first weeks [

18] and first semester [

19,

20].

College transition skills are often a focus in first-year seminar courses and college academic success and persistence has been linked to first-year seminar courses [

12,

21]. In the University of Wyoming Synergy program these core skills are emphasized prior to the start of the first semester, and again throughout the semester in the seminar course. Skills that are often discussed and taught in these seminar courses are note-taking, study skills, time management, interpersonal skills, punctuality, meeting with the instructor, critical reading, academic writing, the importance of extra-curricular activities, and managing an outside job.

In this study we investigate the self-reported results by first-year, academically at-risk students in the University of Wyoming Synergy program by asking the following questions: (1) What skills do students self-identify as important for college success and how do those skills improve from high school through their first two semesters of college? (2) How much time do students spend on academic work from high school through their second semester of college? The purpose of this paper is to highlight underprepared first-year student perceptions of both the skills needed and the amount of time outside of the classroom that are necessary to be a successful student as well as to supply data-driven results for instructors and administrators of first-semester or first-year programs.

4. Discussion

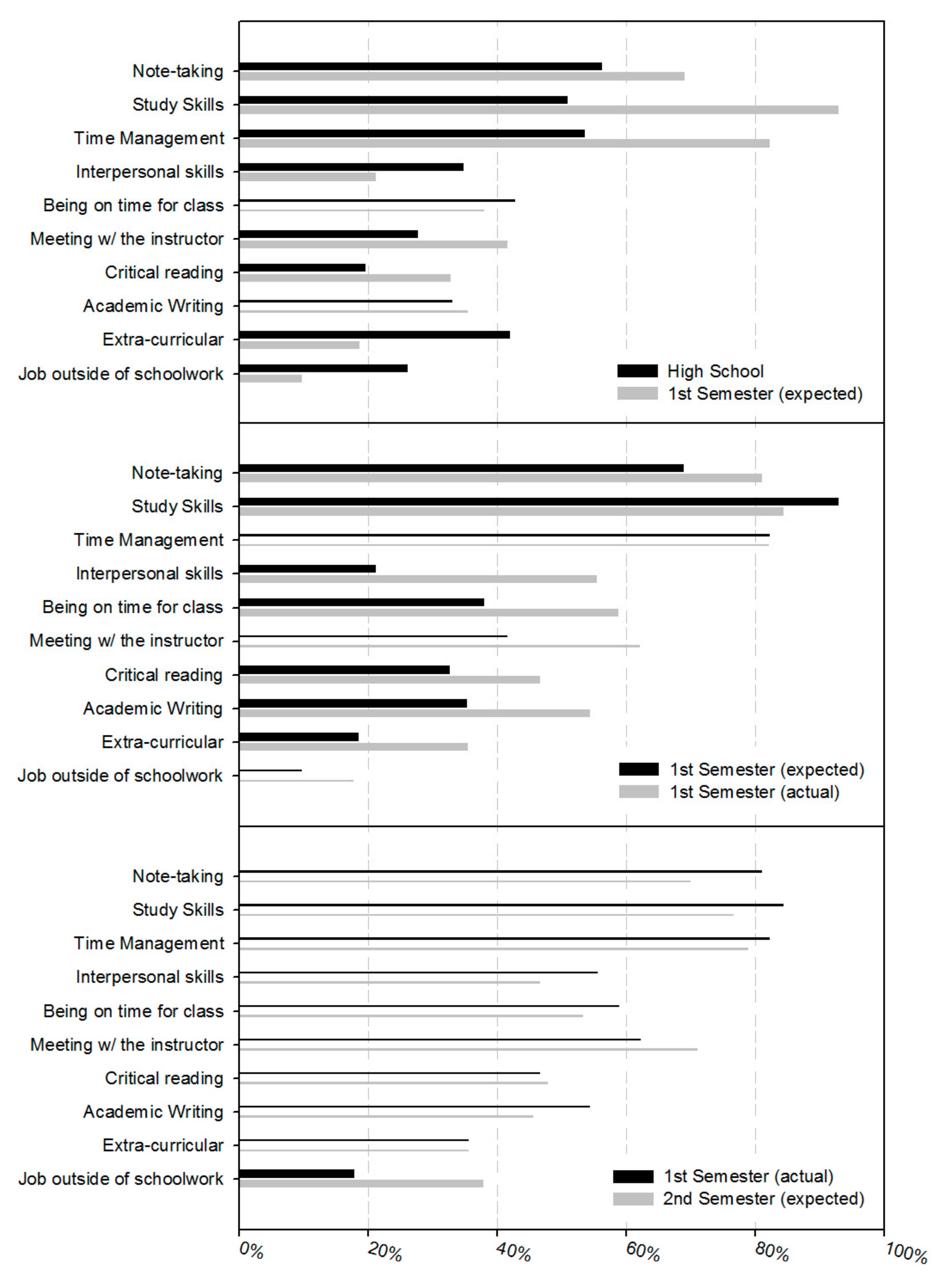

To address the first question of what skills students self-identified as important, results from student surveys at both the start and the end of the first semester found the traditional college skills of note-taking, study skills and time management as being more important than any other skill. Study skills have previously been shown to be positively correlated with academic success [

7,

22], but this work shows a broader set of skills are required. Students largely are correct when they expect these skills to be more important in college, but the skills were still ranked the highest skills in high school as well. One explanation for this difference is that students have a good understanding of skills that cut across all college disciplines; however a similar level of importance is not shown for being on time to class and meeting with the course instructor. It is also possible that the note-taking, study skills and time management skills are more ingrained at the high school level, and so students expect them to still be important, while being on time to class and meeting with the instructor outside of class often are new skills for college students.

Time management skills can often be difficult to teach but worthwhile for the student [

23]. In discussions with other instructors within the Synergy Program, we found a wide range of times when that skill would be emphasized during the semester. These discussions brought out a “Goldilocks” idea that time management is best taught at some point in the middle of the semester. Too early and students feel confident in their abilities to handle their time, since relatively little is being asked of them, and too late in the semester and much of the semester could be wasted for students that are struggling with time management. At some point in time, generally after the first set of exams, we found students were starting to struggle with completing assignments and felt ready to critically discuss their own time management skills. Particular emphasis on time management being a skill that is never mastered and only incrementally improved was also found to be useful as a teaching method.

Interpersonal skills showed the largest jump in importance after the first semester after being the only academic skill to decrease in importance from high school, showing that students realize how important social-based actions (e.g., social study groups, help getting notes when missing class, keeping balance between studying and life) can be in college as compared to their first impressions of college. The work of Entwistle and Entwistle [

7] shows a connection between introverted personalities and academic achievement, so while the students had less of an emphasis on interpersonal skills, there can be a benefit for extroverted students to form peer-group relationships. More recent results from Savitz-Romer, Rowan-Kenyon [

22] show that interpersonal and social skills are often less likely to be the focus of academic support programs, and conclude the institutions may assume students will learn these skills on their own. Out of class activities during the first college semester program helped students get to know each other and there is often just as much of a social transition as there is an academic transition for first semester students. These social skills are frequently learned regardless of the amount of academic time spent on them, but results from this work highlight how much students grow socially their first semester.

Perhaps similar to social skills, extra-curricular activities are expected to be less important coming out of high school than what the student ended up thinking at the end of the first semester. Again, while not found directly in first semester syllabi, students having the skillset to be able to successfully balance in- and out-of-class academic and social activities is ultimately important for student success.

After the learning curve of the first semester of college, students have generally practiced and improved what skills are needed for their future college semester, and previous work has shown this first semester academic success to be critical for likelihood of graduation [

1]. Only at this point does the importance of having a job outside of the classroom show up as a significant increase (

p < 0.05), hypothesized to be correlated with seeing the true cost of attending college as well as incremental increase in time management skills. Employment has been shown to be more likely for low-income students, and students working more than 20 h per week are more likely to leave college during the first year [

24].

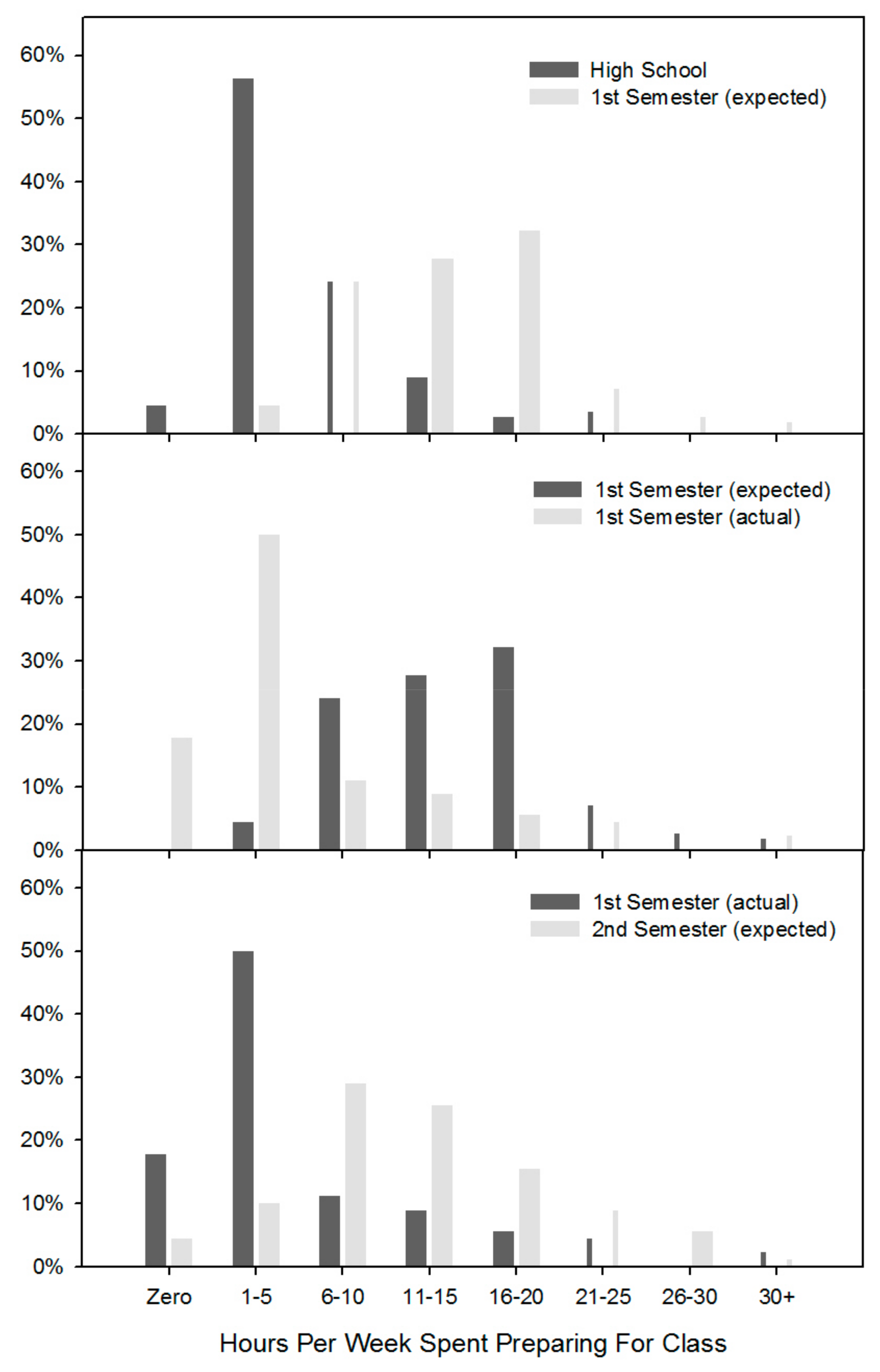

To address the second question of this work, the survey replies asking how much time students spend on preparing for class show a large difference between expectations of how much time will be required and their actual time commitment to academic activities. This is similar to their assessment of skills coming out of high school and starting college, but while expected and actual importance of skills begin to align after one semester, the difference in expected and actual time spent studying does not. At the end of their first semester, students still expect to study more their second semester than they did in their first semester, at a rather large average amount of 10+ hours a week. A recent meta-analysis shows student self-efficacy and motivation as the best predictors of achievement and persistence [

6], and we think this effect is known by students as they feel like they need to spend more time than what is really needed.

It should be noted that the actual time spent studying increased from their high school levels and their expected time needed does go down, and it is possible that how much time students feel like they should be studying and the actual amount of studying will align over the course of their entire college career. The cause of this difference is potentially rooted in how students culturally view college, where they’ve been told it will require significantly more time than high school, but this data suggests it takes longer than one semester for students to match their expectations to reality. Adding to that, some courses that students take their first semester can be less demanding of their time, as compared to upper level courses. We conclude that students, by and large, have a good understanding of how much time it takes to be successful college students, but it takes more than one semester to build up to the level of work needed to be successful college students.

Taken again from discussions with the other instructors within the program, we found that having high level of academic skills were often more important to students then simply spending time outside of the classroom studying. In fact, spending too much time studying often highlighted a relatively lacking skillset; e.g., poor note taking requiring students to first copy other student notes before working on assignments, distracted studying and low time management skills causes wasted hours, or spending a large amount of time working while confused instead of a quick meeting with the instructor to clear up the point of confusion. We found that some students can think that spending a large amount of time alone is enough, while the most successful students tend to either focus on learning skills or already show a high level of competence in their skillset. On the surface, this finding could be contradictory to the grit theory of student performance [

25,

26] where self-motivation is more a factor of performance than student IQ. Personality traits including self-motivation and self-discipline has been suggested by many to lead to high academic achievement, but while students need to be self-motived, they also need to have the correct academic skills in place in order to be successful. Here, for first-year, at-risk students, instructors in these first-year seminar courses have anecdotally found successful students to be focused on skill development.

5. Conclusions

During the critical first semester of college, students are asked to balance a multitude of responsibilities. Working on building the skills needed by students, both academic and social, while managing their time, is difficult and can be overlooked in first semester courses. While this study only used student survey data and did not track student success beyond their first year, this study still provides key insight into the college transition process. We believe that working to develop skills can make a significant difference in students’ ability to succeed in college, regardless of their apparent struggles with implementing skills immediately. Going forward, we suggest additional studies on the relative importance of academic skills by connecting student skills to GPA or retention rates.

A first-year program targeting transition skills should communicate and take measures to address the large gap in expectations and actual behaviors that contribute to academic success. Both academic and social skills should be discussed and emphasis should be placed on incremental improvement. Learning and developing skills is a lifelong process and will last well beyond college. Students need to understand that skill development is an on-going and challenging endeavor—not a quick turn-around. Instructors of first year seminars should be mindful that not all academic skills are equal and that students adjust to college over a longer period of time then the first weeks of their first year.