Networked Professional Learning Communities as Means to Flemish Secondary School Leaders’ Professional Learning and Well-Being

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. Professional Learning Communities: Theory and Practice

- A reflective dialogue through which professionals (a) willingly share relevant professional experiences, questions, concerns, (coping) strategies and material [28,30,46] and (b) inquire colleagues about these same elements [30,41,52,53]. Professional inquiry about a deprivatised practice allows reflection and debate in which current practices are questioned, tacit knowledge becomes explicit and, new ideas are disseminated and explored [46].

- A culture of trust, respect, openness and support is indispensable to use prior experiences and knowledge within a group to the fullest and maximise the prospect of interaction [34,41]. Without it, participants might experience discomfort when discussing difficult topics, causing them to refrain from sharing highly relevant experiences [54], which, in turn, limits knowledge acquisition on a group level and hinders a reflective dialogue.

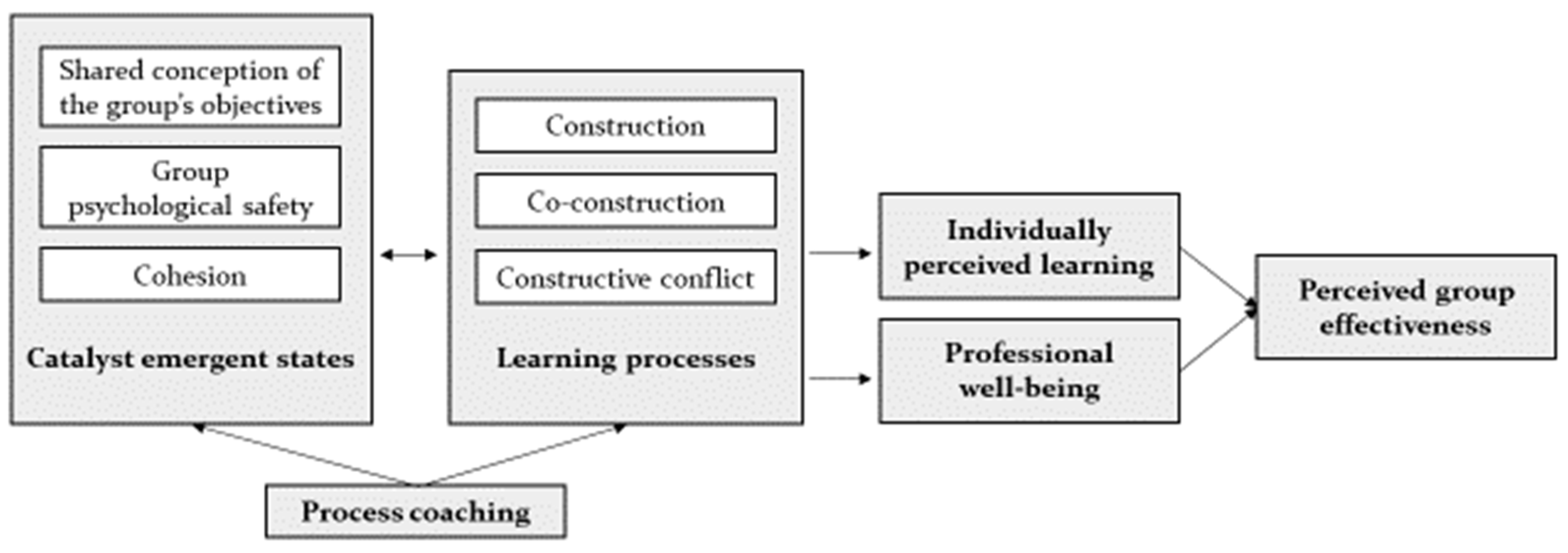

2.2. PLC Development: A Complex of Learning Processes and Group Develeopment

- Team psychological safety indicating the “taken-for-granted beliefs about how others will respond when one puts oneself on the line, such as by asking questions, seeking feedback, reporting a mistake or proposing a new idea” [60] (p.352). In order to feel psychologically safe, a culture of respect and trust among PLC members is indispensable [34,66]. Such a culture is even considered the best predictor of the occurrence of team learning processes [33,39] as learning is facilitated by openness, being allowed to think freely and experiment.

- Cohesion might refer to either social cohesion or task cohesion. In the case of the former, it indicates emotional bonds between group members such as friendship, liking and caring. Social cohesion motivates to helping each other succeed. Task cohesion on the other hand refers to the pleasure an individual and the group as a collective receive from completing an objective. Group members are motivated and committed to the task and regulate their behaviour toward its end [39].

2.3. PLC Development: A Matter of Conscientious Guidance

2.4. Collective or Networked Learning and Professional Well-Being

3. Research Questions

- 1.

- RQs. concerning PLC output and outcomes

- To what extent can PLCs contribute to the professional well-being of Flemish secondary school leaders?

- To what extent can PLCs contribute to the individual professional learning of Flemish secondary school leaders?

- 2.

- RQs. concerning the conditions for successful principal PLCs

- How do learning processes (LPs) within PLCs (i.e., construction, co-construction and constructive conflict) emerge and evolve over time?

- How do the group developmental factors (i.e., CES) of social and task cohesion, group psychological safety and a shared perception of the group’s values and objectives associate with the occurrence of LPs within PLCs?

- 3.

- RQs. concerning the role of a process coach

- Which role (i.e., expert, coach and/or coordinator) do the process coaches fulfil within the PLCs and how does this relate to PLC processes and outcomes?

- Does the role of the process coaches alter over time?

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. A Longitudinal Mixed-Method Approach

4.2. Learning Community Set-Up

4.2.1. PLC 1: Case Context and Background

4.2.2. PLC 2: Case Context and Background

4.2.3. PLC 3: Case Context and Background

4.3. Instruments

4.3.1. Observations and Observation Scheme

4.3.2. Questionnaire

4.3.3. Interviews

4.4. A Case-Study Analysis

5. Results

5.1. PLC 1—A Networked Community of Special Secondary Eduction Principals

5.1.1. LPs and CES at Play ad Interplay

Principals receive a lot of satisfaction out of the fact that they can sit together and talk endlessly about their jobs. Developing a good relationship among each other, for them, appears very important. Something therapeutical almost. And therapeutical is fine but it has its limits: at some point, things need to actually happen […] and they find it very difficult to select things [of what has been shared therapeutically] to implement in their schools (pedagogical counsellor 5—female).

[Principal 10] learns by simply being present and listening. He absorbs: A sponge that takes things with him. Yet, it is not give-and-take: He will partake when you ask him to, but it always strikes me that content-wise, he scores very badly. He repeats the same story whereas the others actually add something every now and then (pedagogical counsellor 5—female).

I thought [the process coach] very understanding and sympathetic towards us and our schools, but when it comes to feedback which made you really think for a moment, for me, that should have been more.

We were ten adults, right? [10 adults] who played a waiting game: ‘We’ll see who takes the lead’. Yet, no one did. We always waited politely for each other to finish. That is not only the responsibility of the ones who lead the conversation.

5.1.2. Process Guiding

The process coach to me served to keep us focused: ‘Do you recall this or that’, really a theoretician who, based on our [shared] examples could put us on our way. However, the end product was too inadequate to truly call it a success (principal 12—female—7 years of experience).

I tend to believe [the pedagogical counsellor’s] knowledge hampered. From the knowledge base she has, she wanted to provide additional clarification too quickly but that stifled the debate among us (principal 12—female—7 years of experience).

5.1.3. To Participate or Not to Participate: PLC Output and Outcomes

Most of the time, when you toss something in the group, you find that you are not the only one with this problem. That, in itself, is sometimes a consolation (principal 7—male—less than one year of experience).

Sharing documents, I tell you: I feel as if I was left empty-handed (principal 8—female—2 years of experience).

5.2. PLC 2—A Networked Community of Mainstream Secondary Eduction Principals

5.2.1. LPs and CES at Play and Interplay

[Ventilating frustration] is all very well but we can’t change those things. You can want something and keep on wanting the same thing. And, a lot of [PLC] time was spend on ventilating frustrations. I found that very annoying—because the answer is ‘no’ and will always remain ‘no’ (principal 5—female—2 years of experience).

It was always just intervision: Talking and bringing things up. I thought, however, the objective was to collectively design material that could find a real implementation in schools (pedagogical counsellor 3).

I believe [the PLC] to be a very safe environment in the sense that we only talked about good practices. If we were to discuss things that go awry and require a solution than it would have been entirely different […] If everyone only comes with something they are good at, safety in itself is less important because you do not have to show your vulnerable side (principal 5—female—2 years of experience).

At a certain point in time, the project card was introduced and for which I had some ideas but it has never been developed thereafter. A shame, I think as I had a lot of questions about [this tool] and am still searching for an answer. I did not receive feedback nor insight in how colleagues filled out this document. A pity because I truly deem this an interesting instrument (principal 6—female—12 years of experience).

Learning is more than simply acquiring information at a certain point in time. To learn, information needs to be processed (principal 4—female—11 years of experience).

5.2.2. Process Guiding

Each time [principal 4 told] the same story. I think I have heard it ten times over the past school year! It is of no values that someone brings things up over and over again. The coach and counsellor who lead the community should be more alert to that […] there should be more feedback from them towards members and their functioning within the group […] For us, it is difficult to address a fellow principal (principal 5—female—2 years of experience).

At the beginning I really enjoyed working with [the process coach and pedagogical counsellor]: they do know a lot and I believe they can support you. But towards the end that all disintegrated a bit: there was more repetition and less new input. It felt like we were going round in circles (principal 6—female—12 years of experience).

5.2.3. To Participate or Not to Participate: PLC Output and Outcomes

It is also about supporting each other. We all do the same job. We all search for a moment to ventilate and listen how [fellow principals] cope. To me, those social and mental aspects are important too. And, those [the PLC] did include (principal 2—male—6 years of experience).

5.3. PLC 3—A Networked Community of Well-Acquinted Secondary Education Principals

5.3.1. LPs and CES at Play and Interplay

[It was] very safe to declare inexperience or put questions forward. Certainly. Everyone dared to show his or her vulnerable side and describe what he or she struggles with (principal/coach 16—female—4 years of experience).

Within our team [the process coach] is seen as someone with experience. Someone that runs her school effectively. She is easily approachable, which is important and partly created safety [within the group] (principal 15—female—3 years of experience).

When we divided tasks, I did notice that in being assigned a certain part, everyone had the sense of honour and duty to actually complete. […] I thought everyone to have completed the task well. That is again prove that making clear arrangements about tasks and deadlines works (principal/coach 16—female—4 years of experience).

I mainly take way from [the PLC] that I was not alone in [dealing with the new framework]. Often I think to myself [about legislative updates]: “I do not understand at all. I do not even know where to start”. Through the discussions I felt at ease: “Together we’ll work things out” (principal 15—female—3 years of experience).

[The more experienced principals] can really contribute while the less experienced principals pose exploratory questions. By formulating an answer [to those questions] I manage to put things straight again in my head (principal/coach 16—female—4 years of experience).

5.3.2. Process Guiding

I try to make the learning community challenging to myself and that is of course a pitfall. When others remain silent, I tend towards filling in this silence by thinking out loud. Which is not always good (principal/coach 16—female—4 years of experience).

5.3.3. To Participate or Not to Participate: PLC Output and Outcomes

At times, we lost our result-oriented focus because we could not get the objective straight. So yes, there is little output at the moment even though we have a highly clarifying document. Of course, we were not able to conclude the trajectory [due to COVID-19] (principal/coach 16—female—4 years of experience).

[…] I hope we can continue during the next school year because, despite the limited output, [the PLC] involved very relevant things: I do have the impression I grew, or know more than I did without the PLC (ibidem).

When I heard from other schools—and principal 16 was always very open to sharing her school’s policy documents—that they still had topics indicated red too, I thought that it wasn’t all that bad. That added greatly to my well-being: thinking I was miles behind while it turned out to be only a few feet (principal 14—male—1 year of experience).

6. Discussion

6.1. PLC Output and Outcomes

6.2. Conditions for Succesful Principal PLCs

6.3. The Role of the Process Coach

7. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forde, C. Leadership for Learning: Educating Educational Leaders. In International Handbook of Leadership for Learning; Townsend, T., MacBeath, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Switzerland, 2011; Chapter 21; pp. 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBeath, J.; O’Brien, J.; Gronn, P. Drowning or Waving? Coping Strategies among Scottish Head Teachers. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2012, 32, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos, G.; Vanblaere, B.; Bellemans, L. Stress En Welbevinden Bij Schoolleiders: Een Analyse van Bepalende Factoren En van Vereiste Randvoorwaarden; SONO/2017.VrijeRuimte/1; Steunpunt Onderwijsonderzoek: Gent, België, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Seven Strong Claims about Successful School Leadership. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2008, 28, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Tuytens, M.; Devos, G.; Kelchtermans, G.; Vanderlinde, R. Transformational School Leadership as a Key Factor for Teachers’ Job Attitudes during Their First Year in the Profession. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2020, 48, 106–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OECD. Positive, High-Achieving Students? What Schools and Teachers Can Do; TALIS, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, M.; Vavik, M. Group Coaching: A New Way of Constructing Leadership Identity? Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2015, 35, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBeath, J. No Lack of Principles: Leadership Development in England and Scotland. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2011, 31, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBeath, J.; Dempster, N.; Frost, D.; Johnson, G.; Swaffield, S. Strengthening the Connections between Leadership and Learning: Challenges to Policy, School and Classroom Practice; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. Teaching in the Knowledge Society; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, V.M.J. Descriptive and Normative Research on Organizational Learning: Locating the Contribution of Argyris and Schön. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2001, 15, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sigurðardóttir, A.K. Studying and Enhancing Professional Learning Community for School Effectiveness in Iceland. Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2005, 3, 178–193. [Google Scholar]

- Aas, M. Professional Development in Education Leaders as Learners: Developing New Leadership Practices. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2017, 5257, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniëls, E.; Hondeghem, A.; Heystek, J. Developing School Leaders: Responses of School Leaders to Group Reflective Learning. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotte, V.; Tynjälä, P.; Hytönen, T. How Do HRD Practitioners Describe Learning at Work? Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2004, 7, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkins, T. Understanding School Leadership and Management Development in England. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2012, 40, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.; da Costa, J. Rethinking Professional Development for School Leaders: Possibilities and Tensions. J. Educ. Adm. Found. 2016, 25, 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, S.G. Multiple Learning Approaches in the Professional Development of School Leaders—Theoretical Perspectives and Empirical Findings on Self-Assessment and Feedback. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2013, 41, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldring, E.; Preston, C.; Huff, J. Conceptualizing and Evaluating Professional Development for School Leaders. Plan. Chang. 2012, 43, 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, S.G. The Impact of Professional Development: A Theoretical Model for Empirical Research, Evaluation, Planning and Conducting Training and Development Programmes. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2011, 37, 837–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsbos, F.A.; Evers, A.T.; Kessels, J.W.M. Learn to Lead: Mapping Workplace Learning of School Leaders. Vocat. Learn. 2016, 9, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bush, T. Preparation and Induction for School Principals: Global Perspectives. Manag. Educ. 2018, 32, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniëls, E.; Hondeghem, A.; Dochy, F. An Integrative Perspective on Leadership and Leadership Development in an Educational Setting: A Systematic Review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 27, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pont, B.; Nusche, D.; Hopkins, D. Improving School Leadership; Policy and Practice; OECD: Paris, France, 2008; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hairon, S.; Goh, J.W.P.; Chua, C.S.K.; Wang, L. A Research Agenda for Professional Learning Communities: Moving Forward. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2017, 43, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prenger, R.; Poortman, C.L.; Handelzalts, A. The Effects of Networked Professional Learning Communities. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 70, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prenger, R.; Poortman, C.L.; Handelzalts, A. Factors Influencing Teachers’ Professional Development in Networked Professional Learning Communities. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 68, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanblaere, B.; Devos, G. The Role of Departmental Leadership for Professional Learning Communities. Educ. Adm. Q. 2018, 54, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanblaere, B.; Devos, G. Relating School Leadership to Perceived Professional Learning Community Characteristics: A Multilevel Analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 57, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, K.S.; Marks, H.M. Does Professional Community Affect the Classroom? Teachers’ Work and Student Experiences in Restructuring Schools. Am. J. Educ. 1998, 106, 532–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogt, J.; Laferrière, T.; Breuleux, A.; Itow, R.C.; Hickey, D.T.; McKenney, S. Collaborative Design as a Form of Professional Development. Instr. Sci. 2015, 43, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voogt, J.; Westbroek, H.; Handelzalts, A.; Walraven, A.; Mckenney, S.; Pieters, J.; Vries, B. De. Teacher Learning in Collaborative Curriculum Design. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K.; Dochy, F.; Raes, E. Team Learning in Teacher Teams: Team Entitativity as a Bridge between Teams-in-Theory and Teams-in-Practice. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2016, 31, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K.; Meredith, C.; Packer, T.; Kyndt, E. Teacher Communities as a Context for Professional Development: A Systematic Review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 61, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C.; Muijs, D. Does School-to-School Collaboration Promote School Improvement ? A Study of the Impact of School Federations on Student Outcomes. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2014, 25, 351–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, M.I.; Rainey, L.R. Central Office Leadership in Principal Professional Learning Communities: The Practice beneath the Policy. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2014, 116, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Haar, S.; Segers, M.; Jehn, K.; Van den Bossche, P. Investigating the Relation Between Team Learning and the Team Situation Model. Small Group Res. 2015, 46, 50–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, E.; Decuyper, S.; Lismont, B.; Van den Bossche, P.; Kyndt, E.; Demeyere, S.; Dochy, F. Facilitating Team Learning through Transformational Leadership. Instr. Sci. 2013, 41, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van den Bossche, P.; Gijselaers, W.H.; Segers, M.; Kirschner, P.A. Social and Cognitive Factors Driving Teamwork in Collaborative Learning Environments: Team Learning Beliefs and Behaviors. Small Group Res. 2006, 37, 490–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minea-Pic, A.; Nusche, D.; Sinnema, C.; Stoll, L. Teachers’ Professional Learning Study: Diagnostic Report for the Flemish Community of Belgium; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, L.; Bolam, R.; McMahon, A.; Wallace, M.; Thomas, S. Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature. J. Educ. Chang. 2006, 7, 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bossche, P.; Gijselaers, W.; Segers, M.; Woltjer, G.; Kirschner, P. Team Learning: Building Shared Mental Models. Instr. Sci. 2011, 39, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooke, N.J.; Salas, E.; Cannon-Bowers, J.A.; Stout, R.J. Measuring Team Knowledge. Hum. Factors 2000, 42, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolam, R.; Mcmahon, A.; Stoll, L.; Thomas, S.; Wallace, M.; Greenwood, A.; Hawkey, K.; Ingram, M.; Atkinson, A.; Smith, M. Creating and Sustaining Effective Professional Learning Communities; DfES Publications: Nottingham, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hord, S.M. Evolution of the Professional Learning Community. J. Staff Dev. 2008, 29, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Vescio, V.; Ross, D.; Adams, A. A Review of Research on the Impact of Professional Learning Communities on Teaching Practice and Student Learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuFour, R. What Is a “Professional Learning Community”? Educ. Leadersh. 2004, 61, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Flückiger, B.; Aas, M.; Nicolaidou, M.; Johnson, G.; Lovett, S. Professional Development in Education the Potential of Group Coaching for Leadership Learning. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2017, 43, 612–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomos, C.; Hofman, R.H.; Bosker, R.J. Professional Communities and Student Achievement—A Meta-Analysis. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2011, 22, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L.M. Improving Impact Studies of Teachers’ Professional Development: Toward Better Conceptualizations and Measures. Educ. Res. 2009, 38, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sutherland, S.; Katz, S. Concept Mapping Methodology: A Catalyst for Organizational Learning. Eval. Program Plan. 2005, 28, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hord, S.M. Learning Together, Leading Together: Changing Schools through Professional Learning Communities; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Newmann, F.M.; Wehlage, G.G. Successful School Restructuring: A Report to the Public and Educators; Center on Organization and Restructuring of Schools: Madison, WI, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.W.; Grant, A.M. From Grow to Group: Theoretical Issues and a Practical Model for Group Coaching in Organisations. Coaching 2010, 3, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.G.; Bailey, D.E. What Makes Teams Work: Group Effectiveness Research from the Shop Floor to the Executive Suite. J. Manag. 1997, 23, 239–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, E.; Kyndt, E.; Decuyper, S.; Van den Bossche, P.; Dochy, F. An Exploratory Study of Group Development and Team Learning. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2015, 26, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelfhout, W. Toward Data for Development: A Model on Learning Communities as a Platform for Growing Data Use. In Data Analytics Applications in Education; Vanthienen, J., De Witte, K., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 37–82. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, M.W.; Talbert, J.E. Professional Communities and the Work of High School Teaching; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.; Kruse, S.; Tarter, C.J. Enabling School Structures, Collegial Trust and Academic Emphasis: Antecedents of Professional Learning Communities. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2016, 44, 875–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Decuyper, S.; Dochy, F.; Van den Bossche, P. Grasping the Dynamic Complexity of Team Learning: An Integrative Model for Effective Team Learning in Organisations. Educ. Res. Rev. 2010, 5, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.J. A Model for Negotiation in Teaching-Learning Dialogues. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 1994, 5, 199–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A. (Ed.) Teaching in the Knowledge Society: Education in the Age of Insecurity; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, G.; Globerson, T. When Teams Do Not Function the Way They Ought To. Int. J. Educ. Res. 1989, 13, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A.S.; Schneider, B. Trust in Schools: A Core Resource for Improvement (Rose Series in Sociology); Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Vegt, G.; Emans, B.; Van de Vliert, E. Motivating Effects of Task and Outcome Interdependence in Work Teams. Group Organ. Manag. 1998, 23, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K.; Boon, A.; Dochy, F.; Kyndt, E. Group, Team, or Something in between? Conceptualising and Measuring Team Entitativity. Front. Learn. Res. 2017, 5, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clutterbuck, D. Coaching the Team at Work; Nicholas Brealey International: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Avgitidou, S. Participation, Roles and Processes in a Collaborative Action Research Project: A Reflexive Account of the Facilitator. Educ. Action Res. 2009, 17, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelfhout, W.; Bruggeman, K.; Bruyninckx, M. Vakdidactische Leergemeenschappen, Een Antwoord Op Professionaliseringsbehoeften Bij Leraren Voortgezet Onderwijs? Eindhoven 2015, 36, 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Margalef, L.; Roblin, N.P. Unpacking the Roles of the Facilitator in Higher Education Professional Learning Communities. Educ. Res. Eval. 2016, 22, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonoubi, R.; Eslami Rasekh, A.; Tavakoli, M. EFL Teacher Self-Efficacy Development in Professional Learning Communities. System 2017, 66, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandmo, C.; Aas, M.; Colbjørnsen, T.; Olsen, R. Group Coaching That Promotes Self-Efficacy and Role Clarity among School Leaders. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 65, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos, G.; Van Petegem, P.; Delvaux, E.; Feys, E.; Franquet, A. De Evaluatie van Scholengemeenschappen in Het Basis-En Secundair Onderwijs; OBPWO-Project 07.02; Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap: Brussel, België, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weißenrieder, J.; Roesken-Winter, B.; Schueler, S.; Binner, E.; Blömeke, S. Scaling CPD through Professional Learning Communities: Development of Teachers’ Self-Efficacy in Relation to Collaboration. ZDM Math. Educ. 2015, 47, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, M.; Paulsen, J.M. National Strategy for Supporting School Principal’ s Instructional Leadership A Scandinavian Approach. J. Educ. Adm. 2019, 57, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazenby, S.; McCulla, N.; Marks, W. The Further Professional Development of Experienced Principals. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, W.; Tomic, E. Existential Fulfillment and Burnout among Principals and Teachers. J. Beliefs Values 2008, 29, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, L.E.; Bauer, S.C. The Role of Isolation in Predicting New Principals’ Burnout. Int. J. Educ. Policy Leadersh. 2010, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fluckiger, B.; Lovett, S.; Dempster, N. Judging the Quality of School Leadership Learning Programmes: An International Search. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2014, 40, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchamma, Y.; Michaud, C. Professional Development of Supervisors through Professional Learning Communities. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2014, 17, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compen, B.; Schelfhout, W. The Role of External and Internal Team Coaches in Teacher Design Teams. A Mixed Methods Study. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borko, H. Professional Development and Teacher Learning: Mapping the Terrain. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkhorst, F.; Poortman, C.L.; van Joolingen, W.R. A Qualitative Analysis of Teacher Design Teams: In-Depth Insights into Their Process and Links with Their Outcomes. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2017, 55, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Waes, S.; Moolenaar, N.M.; Daly, A.J.; Heldens, H.H.P.F.; Donche, V.; Van Petegem, P.; Van den Bossche, P. The Networked Instructor: The Quality of Networks in Different Stages of Professional Development. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 59, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, H.E.; Stock, M.J. Mentoring and Coaching Rural School Leaders: What Do They Need? Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 2010, 18, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daresh, J.C.; Alexander, L. Beginning the Principalship: A Practical Guide for New School Leaders; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S. Transformation of Professional Identity in an Experienced Primary School Principal. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2017, 45, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Azah, V.N. Characteristics of Effective Leadership Networks. J. Educ. Adm. 2016, 54, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, D. Nachhaltige Wege Vom Wissen Zum Handeln. Beiträge zur Lehrerinnen-und Lehrerbildung 2001, 19, 157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Handelzalts, A. Collaborative Curriculum Development in Teacher Design Teams. In Collaborative Curriculum Design for Sustainable Innovation and Teacher Learning; Pieters, J., Voogt, J., Roblin, N.P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vangrieken, K.; Dochy, F.; Raes, E.; Kyndt, E. Teacher Collaboration: A Systematic Review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 15, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K. The Professional Development of Principals: Innovations and Opportunities. Educ. Adm. Q. 2002, 38, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stewart, G.L. A Meta-Analytic Review of Relationships between Team Design Features and Team Performance. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, L.; Hondeghem, A.; Schelfhout, W. The Emergence of Leadership for Learning Beliefs among Flemish Secondary School Leaders. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, M.; Clark, M.; James-Burdumy, S.; Tuttle, C.; Kautz, T.; Knechtel, V.; Dotter, D.; Wulsin, C.S.; Deke, J. The Effects of a Principal Professional Development Program Focused on Instructional Leadership; NCEE 2020-0002; Institute of Education Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DeFilippis, E.; Impink, S.; Singell, M.; Polzer, J.T.; Sadun, R. Collaborating During Coronavirus: The Impact of COVID-19 on the Nature of Work. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

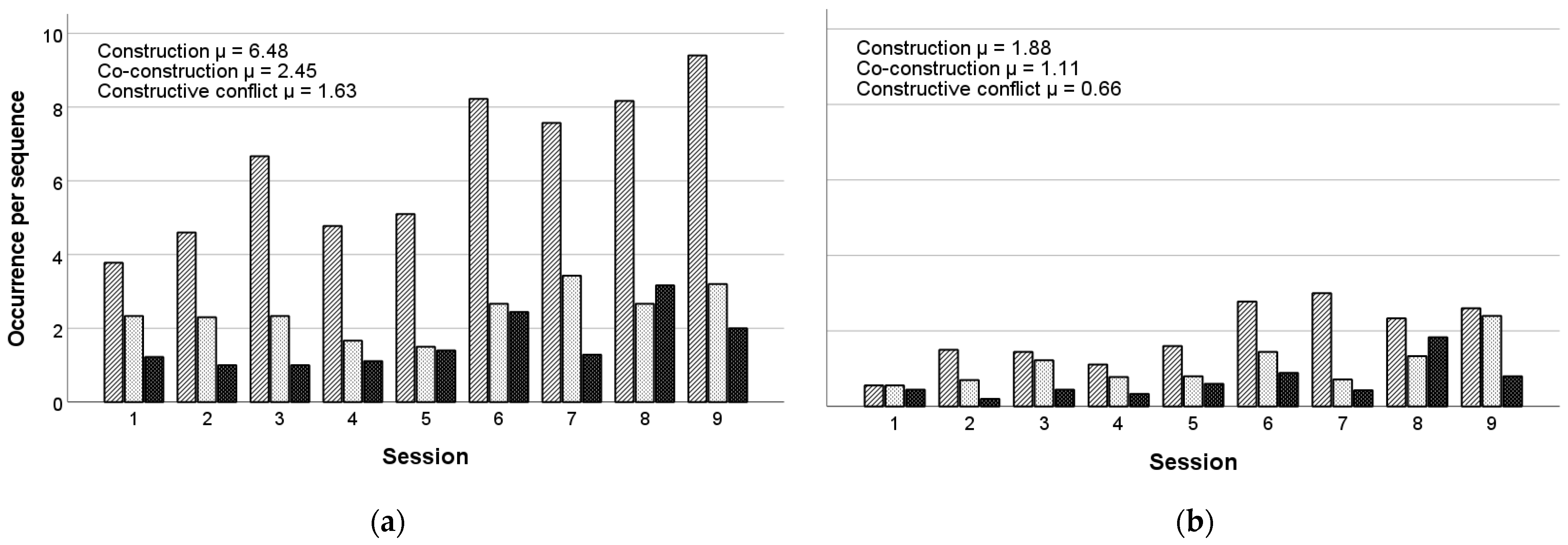

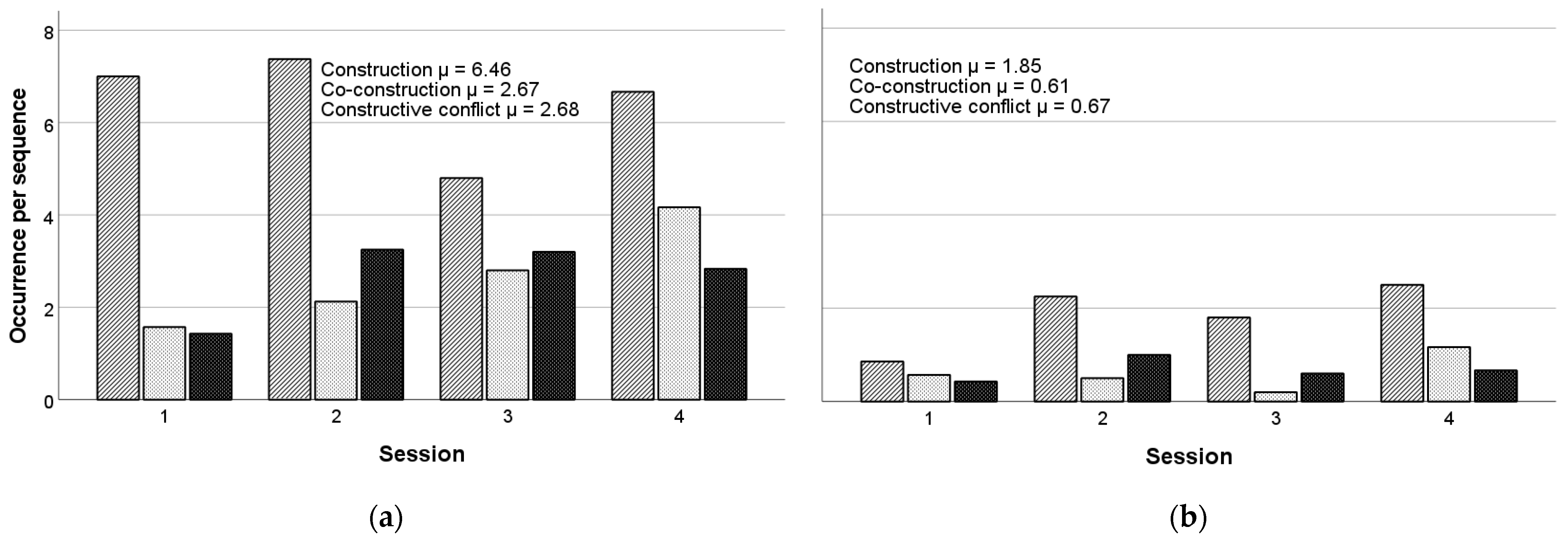

= construction activities on average per sequence;

= construction activities on average per sequence;  = co-construction activities on average per sequence;

= co-construction activities on average per sequence;  = constructive conflict activities on average per sequence:. Note (1). The frequencies presented in Figure 2, panel (b) are based on the activity span of two process coaches. Note (2). ‘μ’ expresses the average occurrence of each LP type over the course of nine sessions.

= constructive conflict activities on average per sequence:. Note (1). The frequencies presented in Figure 2, panel (b) are based on the activity span of two process coaches. Note (2). ‘μ’ expresses the average occurrence of each LP type over the course of nine sessions.

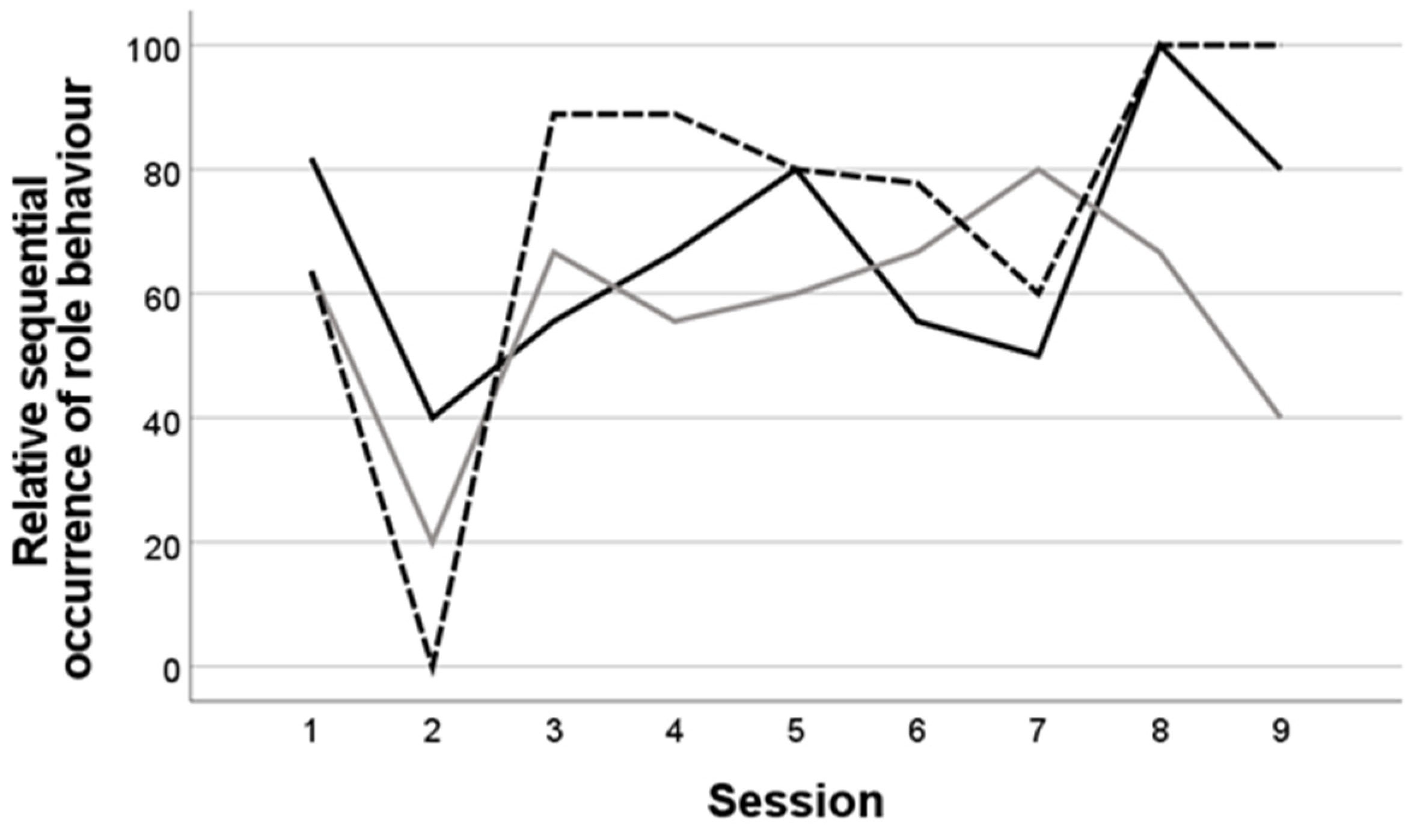

= construction activities on average per sequence;

= construction activities on average per sequence;  = co-construction activities on average per sequence;

= co-construction activities on average per sequence;  = constructive conflict activities on average per sequence:. Note (1). The frequencies presented in Figure 2, panel (b) are based on the activity span of two process coaches. Note (2). ‘μ’ expresses the average occurrence of each LP type over the course of nine sessions.

= constructive conflict activities on average per sequence:. Note (1). The frequencies presented in Figure 2, panel (b) are based on the activity span of two process coaches. Note (2). ‘μ’ expresses the average occurrence of each LP type over the course of nine sessions.

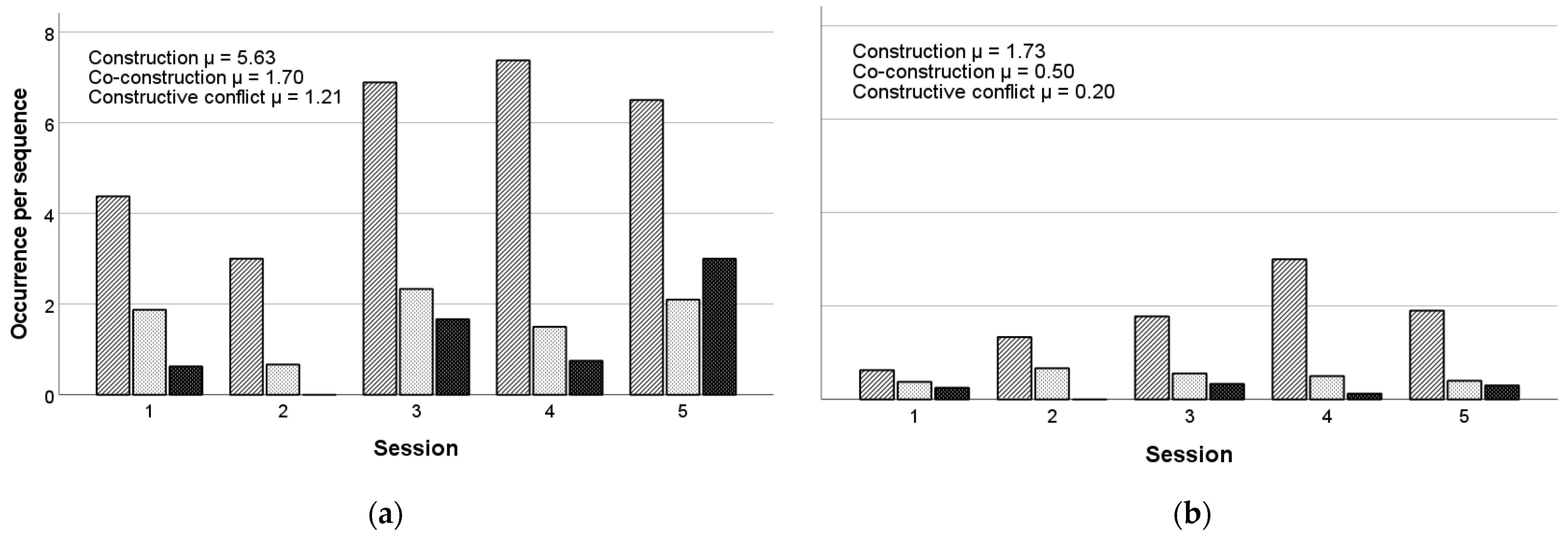

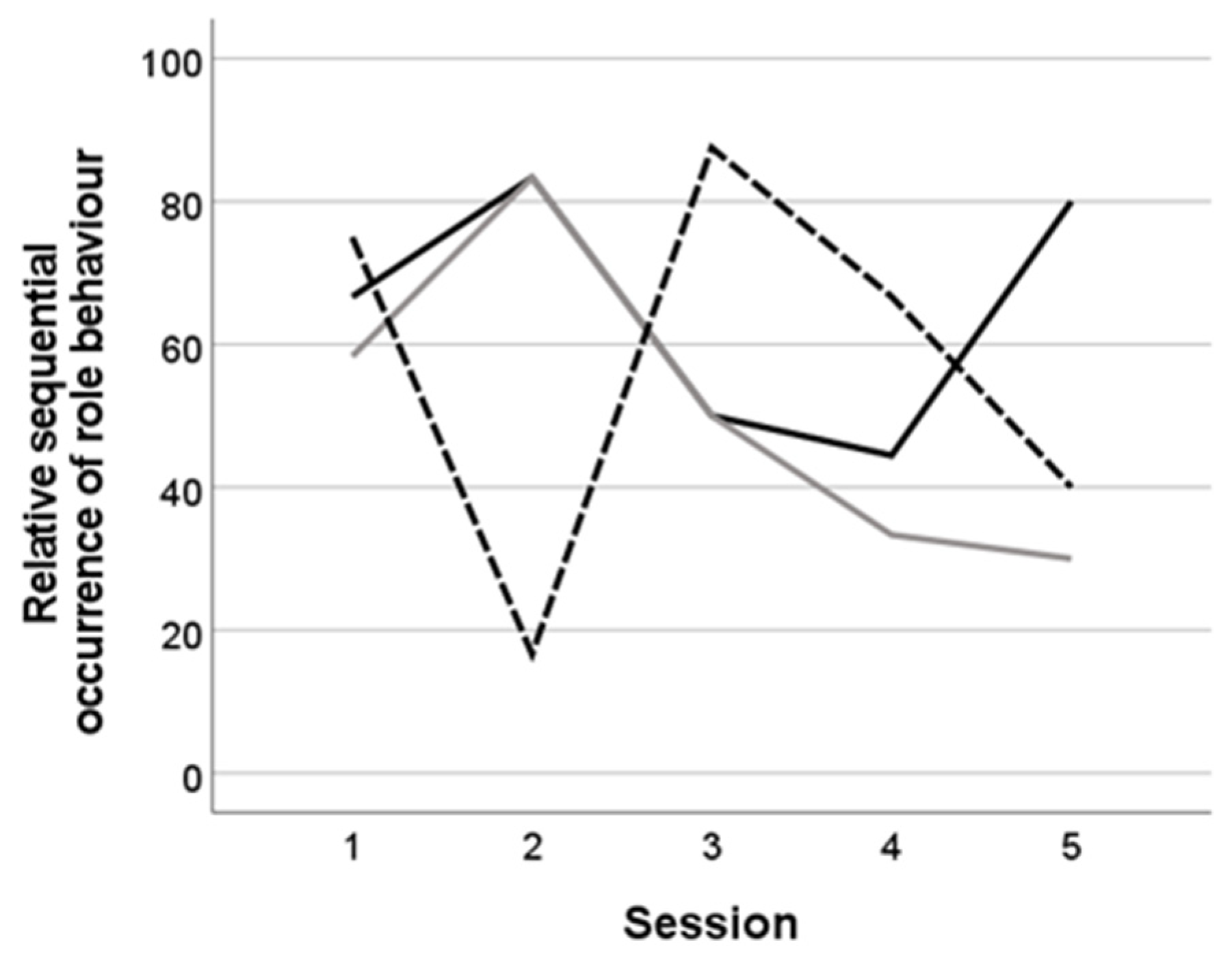

= construction activities on average per sequence;

= construction activities on average per sequence;  = co-construction activities on average per sequence;

= co-construction activities on average per sequence;  = constructive conflict activities on average per sequence. Note (1). The frequencies presented in Figure 4, panel (b) are based on the activity span of two process coaches. Note (2). ‘μ’ expresses the average occurrence of each LP type over the course of five sessions.

= constructive conflict activities on average per sequence. Note (1). The frequencies presented in Figure 4, panel (b) are based on the activity span of two process coaches. Note (2). ‘μ’ expresses the average occurrence of each LP type over the course of five sessions.

= construction activities on average per sequence;

= construction activities on average per sequence;  = co-construction activities on average per sequence;

= co-construction activities on average per sequence;  = constructive conflict activities on average per sequence. Note (1). The frequencies presented in Figure 4, panel (b) are based on the activity span of two process coaches. Note (2). ‘μ’ expresses the average occurrence of each LP type over the course of five sessions.

= constructive conflict activities on average per sequence. Note (1). The frequencies presented in Figure 4, panel (b) are based on the activity span of two process coaches. Note (2). ‘μ’ expresses the average occurrence of each LP type over the course of five sessions.

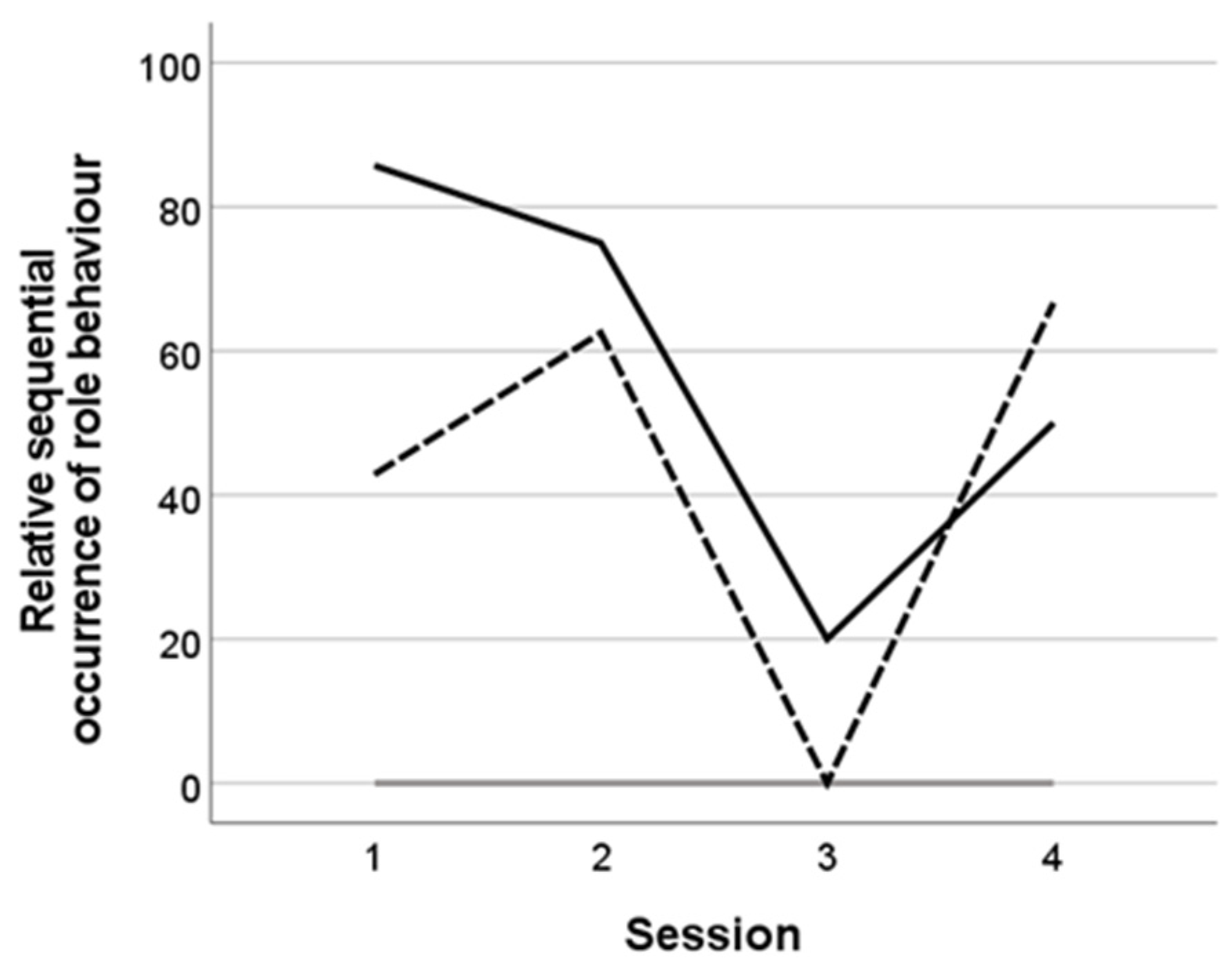

= construction activities on average per sequence;

= construction activities on average per sequence;  = co-construction activities on average per sequence;

= co-construction activities on average per sequence;  = constructive conflict activities on average per sequence. Note (1). The frequencies presented in Figure 6, panel (b) are based on the activity span of one process coach. Note (2). ‘μ’ expresses the average occurrence of each LP type over the course of four sessions.

= constructive conflict activities on average per sequence. Note (1). The frequencies presented in Figure 6, panel (b) are based on the activity span of one process coach. Note (2). ‘μ’ expresses the average occurrence of each LP type over the course of four sessions.

= construction activities on average per sequence;

= construction activities on average per sequence;  = co-construction activities on average per sequence;

= co-construction activities on average per sequence;  = constructive conflict activities on average per sequence. Note (1). The frequencies presented in Figure 6, panel (b) are based on the activity span of one process coach. Note (2). ‘μ’ expresses the average occurrence of each LP type over the course of four sessions.

= constructive conflict activities on average per sequence. Note (1). The frequencies presented in Figure 6, panel (b) are based on the activity span of one process coach. Note (2). ‘μ’ expresses the average occurrence of each LP type over the course of four sessions.

| Feature | PLC 1 | PLC 2 | PLC 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main objective | Organisational innovation in line with learning community principles | Organisational innovation in line with learning community principles | Policy and tool development for the new framework on educational quality |

| Composition | |||

| Number of principals | 7 (10) 1,2 | 8 (12) 1,2 | 7 (8) 2 |

| Attendance rate | 73% | 64% | 86% |

| Acquainted | Yes–rudimentarily | No | Yes–well |

| Principal background | Special secondary | Mainstream secondary | Mainstream secondary |

| Process coach(es) | 2–External | 2–External | 1–Internal |

| Location | Flanders—various locations | Flanders—various locations | Antwerp—fixed location |

| Duration | |||

| Timeframe | May 2018–May 2020 | May 2018–May 2020 | September 2019–October 2020 |

| Sessions | 9 sessions | 6 (5) 3 sessions | 4 sessions |

| Frequency | Every 3 months | Every 3 months | Every month |

| Scheduled session duration | 2 h | 2 h | 2 h |

| Demographics (at start trajectory) | |||

| Gender—female principals Years of principal experience | 71.4% 4 years and 4 months | 62.5% 5 years and 8 months | 71.4% 7 years and 6 months |

| Experience in leading position outside education | 14.3% | 37.5% | N/A |

| Variables and Measures | Observation Scheme | Survey Principals | Interviews Principals | Interviews Pedagogical Counsellors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning processes (LPs) | ||||

| Construction | x | |||

| Co-construction | x | |||

| Constructive conflict | x | |||

| Catalyst emergent states (CES) | ||||

| Group psychological safety | x | x | x | |

| Cohesion (social and task) | x | x | x | |

| Shared conception objectives | x | x | x | |

| Group effectiveness | x | x | ||

| Leadership | ||||

| Perceived value | x | x | ||

| Role 1-Expert | x | x | ||

| Role 2-Coach | x | x | ||

| Role 3-Coordinator | x | x | ||

| Personal outcomes | x | x | ||

| Practical output | x | x |

| LP | λ | t (k → k) | Observed Start Value (Xstart) | Probability (X ≤ Xstart) ~ Pois (λ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction | 50 | 2′19′′ | 25 | 0.0001 *** |

| Co-construction | 19 | 6′07′′ | 18 | 0.4695 |

| Constructive conflict | 12 | 9′14′′ | 9 | 0.2424 |

| Overall | 81 | 1′32′′ | 56 | 0.0021 ** |

| PLC 1 | PLC 2 | PLC 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CES | μ (σ) | μ (σ) | μ (σ) |

| Group psychological safety | 1.31 (0.40) | 1.44 (0.43) | 1.70 (0.26) |

| Social cohesion | 0.91 (0.44) | 0.90 (0.52) | 1.00 (0.20) |

| Task cohesion | 0.33 (0.27) | −0.133 (0.38) | 0.75 (1.10) |

| Shared conception of group objectives | 0.33 (0.19) | 0.27 (0.60) | 1.08 (0.96) |

| Group effectiveness | 0.48 (0.57) | 0.95 (0.62) | 1.06 (0.69) |

| PLC Outcomes | PLC 1 (n = 7) | PLC 2 (n = 5) | PLC 3 (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal outcomes | |||

| Job enthusiasm | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Job satisfaction | 14% | 20% | 0% |

| Self-efficacy | 29% | 40% | 50% |

| Lowered feeling of professional isolation | 71% | 60% | 75% |

| Feeling one can call upon others for help | 43% | 80% | 100% |

| Feeling recognised and acknowledged | 71% | 20% | 50% |

| The ability to ventilate frustrations and concerns | 86% | 100% | 75% |

| Practical output | |||

| Inspiration | 71% | 60% | 75% |

| Knowledge about (sharing leadership, motivating personnel to collective responsibility taking and/or) learning community functioning | 86% | 100% | 25% |

| Concrete tools or material to take away and/or implement | 14% | 0% | 100% |

| Strengthening of the ability to critically reflect on one’s professional experiences | 71% | 100% | 100% |

| Answers to specific policy challenges or questions they had at the start | 43% | 60% | 100% |

| LP | λ | t (k → k) | Observed Start Value (Xstart) | Probability (X ≤ Xstart) ~ Pois (λ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction | 43 | 2′40′′ | 34 | 0.0940 |

| Co-construction | 13 | 8′51′′ | 14 | 0.6751 |

| Constructive conflict | 9 | 12′25′′ | 5 | 0.1157 |

| Overall | 65 | 2′06′′ | 53 | 0.0735 |

| LP | λ | t (k → k) | Observed Start Value (Xstart) | Probability (X ≤ Xstart) ~ Pois (λ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction | 50 | 2′19′′ | 54 | 0.7423 |

| Co-construction | 20 | 5′38′′ | 12 | 0.0390 * |

| Constructive conflict | 21 | 5′36′′ | 11 | 0.0129 * |

| Overall | 91 | 1′17′′ | 77 | 0.0757 |

| Variables | PLC 1 | PLC 2 | PLC 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Team learning processes | |||

| Construction | ↑ | = | = |

| Co-construction | = | = | ↑ |

| Constructive conflict | = | = | ↑ |

| Process coach | |||

| Ascribed construction activities | 28% | 31% | 29% |

| Ascribed co-construction activities | 45% | 39% | 24% |

| Ascribed constructive conflict activities | 41% | 22% | 26% |

| Overall activity level TLPs | 34% | 32% | 26% |

| Observed role behaviour | Coach | Coordinator | Coordinator |

| Expected role behaviour | Expert–Coordinator | Expert–Coach | Coordinator |

| Perceived role behaviour | Coach | Expert–Coach | Coordinator |

| CES | |||

| Group psychological safety | Rather good | Rather good | Good |

| Social cohesion | Fair | Fair | Rather good |

| Task cohesion | Adequate | Rather poor | Fair |

| Shared conception of group objectives | Adequate | Adequate | Rather good |

| Group effectiveness | Adequate | Fair | Rather good |

| Main outcomes and output | |||

| Personal level | Professional isolation ↓ Ability to ventilate frustration ↑ | Feeling one can call for help ↑ Ability to ventilate frustration ↑ | Knowing who to call for help ↑ Self-efficacy and confidence ↑ |

| Practical level | Acquisition of knowledge Acquisition of inspiration | Acquisition of knowledge Acquisition of inspiration | Tangible document and tools Answers to policy questions |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coenen, L.; Schelfhout, W.; Hondeghem, A. Networked Professional Learning Communities as Means to Flemish Secondary School Leaders’ Professional Learning and Well-Being. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090509

Coenen L, Schelfhout W, Hondeghem A. Networked Professional Learning Communities as Means to Flemish Secondary School Leaders’ Professional Learning and Well-Being. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(9):509. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090509

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoenen, Laurien, Wouter Schelfhout, and Annie Hondeghem. 2021. "Networked Professional Learning Communities as Means to Flemish Secondary School Leaders’ Professional Learning and Well-Being" Education Sciences 11, no. 9: 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090509

APA StyleCoenen, L., Schelfhout, W., & Hondeghem, A. (2021). Networked Professional Learning Communities as Means to Flemish Secondary School Leaders’ Professional Learning and Well-Being. Education Sciences, 11(9), 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090509