Abstract

Concept Mapping (CM) is a learning strategy to organize and understand complex relationships, which are particularly characteristic of the natural science subjects. Previous research has already shown that constructing concept maps can promote students’ meaningful learning in terms of deeper knowledge and its more flexible use. While researchers generally agree that students need to practice using CM successfully for learning, key parameters of effective CM training (e.g., content, structure, and duration) remain controversial. This desideratum is taken up by our study, in which three different training approaches were evaluated: a CM training with scaffolding and feedback vs. a CM training without additional elements vs. a non-CM control training. In a quasi-experimental design, we assessed the learning outcome of N = 73 university students who each had participated in one of the trainings before. Our results suggest that an extensive CM training with scaffolding and feedback is most appropriate to promote both CM competence and acquisition of knowledge. From an educational perspective, it would therefore be advisable to accept the time-consuming process of intensive practice of CM in order to enable students to adequately use of the strategy and thus facilitate meaningful learning in terms of achieving sustained learning success.

1. Introduction

Natural science subjects, such as physics or chemistry, primarily deal with highly abstract topics including various complex relationships [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. In a similar manner, the subject of biology demands the learners’ conceptualization considering complex relationships [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. As particular attention is paid to inter- and intra-systemic relationships to describe, explain, and predict interdependencies, for example between different levels of biological systems [16,17], a corresponding challenge for learners is to know, understand, and handle these sometimes highly abstract concepts. In contrast to mere declarative (factual) knowledge, this knowledge about the relations between different topics is called conceptual knowledge. However, empirical studies point out profound difficulties for learners regarding knowledge acquisition [6,14,15,18,19,20]. In particular, the demanding cognitive processes of organization and elaboration (i.e., an integration of new information into structures of prior knowledge) which are necessary when learning requires conceptual reasoning, seem to pose a particular challenge to learners [8,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

Cognitive processes of organization and elaboration can be fostered by respective learning strategies [32]. Organization strategies can be used to condense and structure new information regarding its semantic composition, for example by summarizing texts or constructing concept maps, both requiring in-depth processing of learning material. Elaboration strategies, such as activating prior knowledge, taking notes, asking questions, or developing related ideas, are intended to foster semantically oriented understanding (in-depth strategies) on the one hand, as well as permanent retention via cueing (surface strategies) on the other hand. By using organization an elaboration learning strategies, new information can be meaningfully integrated into prior knowledge.

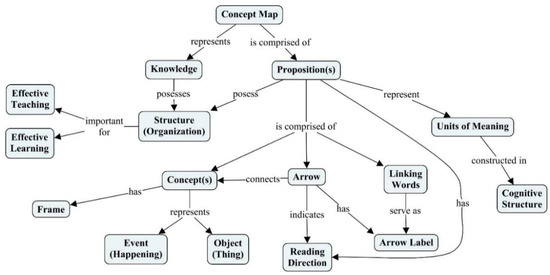

Previous empirical findings suggest that concept mapping (CM) effectively supports organization and elaboration processes as well as conceptual reasoning, and thus, can facilitate a deeper understanding and more organized knowledge acquisition [33,34,35,36,37,38]. CM can be categorized as an in-depth cognitive learning strategy that allows for analysis and reconstruction of the significance of text-based learning material by extracting its central concepts/terms and their interrelations. The result is represented by a combination of graphic and linguistic elements, the concept maps, that can be construed as structural and semantic extensions of mind maps which tend to be more associative [10,14,34,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Concept maps form diagrams, in which concepts are represented by “nodes” that are connected by arrows to indicate their interrelation. To indicate the exact nature of this interrelation, the arrows are labeled to determine the reading direction. Two linked concepts form a so-called proposition, the smallest meaningful unit of a concept map [12,47,50,51,52,53] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A concept map representing principles of the CM learning strategy.

Due to their characteristics’ potential regarding comprehension-oriented learning, concept maps have received a lot of attention from educators since their invention [38,46,47,54,55]. Educational books of biology for school and university level have already started to add CM to their list of recommended learning strategies [56,57]. While teachers are trying to adopt the practice, however, some of them report that integrating CM in classrooms poses certain challenges, since implementation of CM seems quite time-consuming because students are often struggling with selecting concepts and links [58,59]. Accordingly, the main problem for learner seems to be that operating with an unfamiliar strategy for a longer time binds cognitive capacity for this strategy’s monitoring although this capacity is actually required for knowledge acquisition [32]. Consequently, beginners often lack the skills to use CM effectively, and they are unable to tap its full potential [60,61]. This makes the importance of appropriate CM training an essential aspect of the strategy’s effectiveness. To this, Hilbert and Renkl [60] note that “an ideal training method for students on how to use concept mapping that is effective, efficient, and directed to the typical needs of beginners in mapping, is missing at present” (p. 55). More recently, Roessger et al. [62] have pointed out that “few researchers have broached the best way to teach concept mapping” (p. 12). It is therefore hardly surprising that results from studies on the strategy’s effectiveness can differ since CM has been used in different subject areas (STEM vs. non-STEM), with different goals (as a learning vs. a diagnostic tool), in different ways (studying vs. creating concept maps), and in different settings (individual vs. collaborative CM exercise) [38].

If researchers are unable to determine effective CM training conditions, even though training represents one of the strategy’s key factors for its effectiveness, different results in CM research could be also attributed to inconsistent training conditions. Therefore, our study tries to determine the effectiveness of different CM training conditions by focusing on what makes CM effective to facilitate meaningful learning in terms of achieving sustained learning success.

1.1. Concept Mapping from a Cognitive and Metacognitive Perspective

Ausubel [63,64] linked effective processes and products of meaningful learning to certain requirements: learners should proactively seek an integration of newly learned information into their existing networks of prior knowledge and establish corresponding relationships to it, for example by using learning strategies of elaboration and organization (see Section 1). In addition, prior knowledge itself should be well organized and consolidated. Finally, the learning material should be as clearly and comprehensibly designed as possible, e.g., by including explicit indications of potential relational connections to other elements within a respective field of knowledge [50,65].

On the cognitive level, the linking of terms/concepts using CM facilitates the integration of new information into prior knowledge structures in terms of elaboration. Furthermore, CM helps the learner in terms of organization by providing a frame that can be used to structure new information. This way, all information is not only reduced to its essentials but also represented in a way that facilitates processing according to semantic network models [66,67,68,69,70]. Cox [71] and other researchers [72] attribute these strategies’ benefits to activation of self-explanatory activities during the learning process. Consequently, the externalization of knowledge by using concept maps allows the recipient to simply read the information and access it more easily, since concept map-bound information does not have to be continually kept in mind [71]. This externalization of the assumed cognitive processes and structures of representation is also associated with the development of coherent mental knowledge structures [73] and the relief of the strain on working memory [47,74,75]. Beyond this simplification function, the concept map construction itself is expected to result in a more in-depth analysis of the learning material which, in turn, predicts better and long-lasting learning outcome [50,60,67,76,77,78]. Finally, regarding the metacognitive level, it is assumed that CM is associated with more efficient workflow monitoring skills and better identification of difficulties in understanding or knowledge gaps [32,52,60,67,79].

Concept maps, therefore, represent reliable and valid measures of how well learners organize declarative knowledge in a domain [80]. Correspondingly, certain features of a concept map can be used to draw conclusions about associated cognitive processes during learning from texts using CM. Especially the complexity of propositions specified during construction indicates (more or less) distinguishable cognitive processes: (1) recall-suggesting (R-) propositions are represented by relations that are explicitly mentioned in the learning material, (2) organization-suggesting (O-) propositions are represented by relations, that are not explicitly mentioned in the learning material, but constructed, and (3) elaboration-suggesting (E-) propositions are represented by relations between concepts of which at least one was not explicitly mentioned in the learning material but derived from the learners’ prior knowledge.

1.2. Concept Mapping, Prior Knowledge, and Cognitive Load

The structural model of cognition from McClelland et al. [81] considers relevant (prior) knowledge activated during information processing as a central element of information integration. However, this prior knowledge can contradict the knowledge to be acquired, i.e., learners’ prior knowledge inhibits learning, as new information cannot be meaningfully integrated into the existing network [82]. For educators, this means that the influence of learners’ prior knowledge on learning activities must be considered in terms of activating corresponding processes as precisely as possible when dealing with new tasks [83,84,85,86,87,88].

With particular regard to the importance of (structured and activated) prior knowledge for the efficacy of learning aids and learning strategies, Hasselhorn and Gold [75] point out the reverse U-functional relationship between these two variables: if the learners’ prior knowledge ranges on a medium level, they can benefit from provided learning aids best, whereas higher or lower levels of prior knowledge are associated with lower profit. If teachers fail to adapt learning strategies to the learners’ levels of competence, experience, and prior knowledge, their learning success decreases, even in the case of usually high-performance students. These high achievers already use learning strategies that work well for them. If they are asked to replace them by using another learning strategy offering no additional profit, they will usually show a comparatively poor learning outcome. This phenomenon has become known as the expertise reversal effect [89,90,91] and could also be an example of aptitude treatment interaction [90,92,93]. A detailed explanation for this decline in learning success is based on Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) [94,95,96,97], which highlights the importance of working memory capacity during learning activities. Regarding the expertise reversal effect, it can be assumed that the learners’ cognitive capacity is not exclusively bound by the processing of new information but rather by coping with the unknown methodical procedure when using an unfamiliar learning strategy.

1.3. Training in Concept Mapping

If learners are introduced to a new learning strategy, those without supportive prompting often fail to actively and specifically add this new strategy to their cognitive learning strategy repertoire (production deficit) or fail to gain an advantage from using it (deficit in use). The same is reported for metacognitive knowledge about learning strategies and corresponding skills for monitoring the own learning process while using a strategy [75,98]. In this respect, Cañas et al. [34] critically point out that unfamiliarity with CM may cause an unnecessary burden on a learner’s cognitive load which makes successful learning impossible. Michalak and Müller [44] found that persons who lacked CM experience accordingly stated to be unfamiliar with a holistic view of a graphic and the authors concluded that methodical guidance is necessary. This is not a novel idea, as Jüngst and Strittmatter [99] have stated that the adequate use of CM requires sufficient knowledge about the strategy and its use which is why they proposed that only after 10 to 15 self-constructed maps, learners are sufficiently familiar with CM as a learning tool. Accordingly, several weeks of training with repeated intervention and feedback measures were implemented in some studies [100,101]. In contrast, authors such as Jonassen et al. [102] state that “concept mapping is relatively easy to learn” (p. 162).

Overall, the construction of concept maps requires procedural knowledge which is defined as the “know how” (meaning some form of action carried out), whereas declarative knowledge is defined as “know that” [103] (p. 219), including conceptual knowledge regarding relationships between respective concepts [104]. Neglecting more detailed aspects of distinction, the repetition of procedural knowledge has been found to have significant learning effects: Repeating an action can even make the execution itself unnecessary, as the final result can be recalled as declarative knowledge [105]. For example, if a student had to use an instruction (e.g., step-by-step explanation from a handout) on how to construct a proposition in a concept map, by repetition, he or she would sooner or later know the answer without this instruction. In addition, special series of processes can be generated through repetition of actions and routines can be established. These routines put less strain on attentional processes and can be executed faster with time. The same is true for skills such as reading: if they have been practiced for an extended period, retrieval from long-term memory is accomplished with very little effort, which is referred to as automaticity [106], and a relief of working memory can be observed [107].

For these reasons, many researchers mention an importance of CM training before its use [60,62,66,68,69,99,108,109,110,111,112,113]. However, for such training measures to have a positive effect on learning performance, they should be carried out long enough to ensure that using the new strategy becomes sufficiently routine. In this respect, questions arise as to (1) what content should be trained (2) in which amount of time, and (3) in which intensity using (4) which specific methods? Most training approaches reported in literature concerning CM are adapted from Novak and Cañas [47]. However, most of these studies only touch on CM training since they predominantly focus on the effectiveness of the learning tool itself. Therefore, consistent recommendations concerning specific training designs could not be deduced yet. Consequently, within the empirical findings concerning the training design, central parameters vary widely and are unsystematically associated with different learning outcomes [110,114,115,116]. For example, these varying parameters refer to:

- (a)

- Training duration (10 min to three hours) [18,108,117,118,119];

- (b)

- Training intensity (once or several times, sometimes over several weeks) [82,120];

- (c)

- Instruction method (direct training to acquire declarative and procedural knowledge vs. indirect training to acquire exclusively declarative knowledge) [18,21,60,69,121]; as well as

- (d)

- Self-activity of the learners (level of support, such as scaffolding in instructions and task material) [10,36,66,67,113,122,123,124,125,126,127].

Considering the findings of Hay et al. [117], who stated that CM can be taught in a single session within 10–20 min, and that “most students will find another 20–30 min sufficient to construct a reasonable map” (p. 302), Brandstädter et al. [22] used a comparable timeframe, but implemented a training approach, that included both theory- and practice-oriented elements from the beginning. Additionally, they varied the degree of directedness (highly directed vs. non-directed) during the course of the two training sessions. Based on their results, the authors recommend using a highly directed approach, including practical elements, as the validity for an assessment of students’ conceptual reasoning using CM was positively influenced by this approach. Sumfleth et al. [69] also based their design on previous studies examining the benefits of active practice of concept map construction [36,67]. The authors developed a CM training booklet for grade 10 chemistry classes and compared a CM training group to a control group that received only a short introduction to CM. The CM training consisted of three sessions (introduction, demonstration of the CM strategy, and exercises), in which students were given 60 min to complete the booklet. The control group read the same texts but did not use CM. Results show that learners in the trained group were able to generate significantly better concept maps than the untrained learners. In contrast, Jegede et al. [110] also trained students in CM over a three-week period, including theoretical and practical phases, but focused specifically on content-related learning outcome. Their results show that their CM training led to significantly better test results in biology than a traditional teaching strategy. Regarding additional training measures (e.g., prompting), Hilbert et al. [66] compared a CM training group that received prompts to a second training group that did not. They found that participants who received prompts during CM showed a better learning outcome compared to the other group. Results of a follow-up test, however, indicated that learners, who were provided with prompts once, were not able to add them to their skill repertoire and continue using CM on their own. Another study of Pearsall et al. [120] focused on the effect of additional feedback during CM training. They trained students on CM in a single 3 h session but provided students with individual feedback on some concept maps which had to be created during their regular semester of study that followed. Analyses of the students’ concept maps showed that the students were obviously able to use the continuous feedback to construct concepts maps indicating more and more elaborated and well-differentiated knowledge structures over the course of time.

Based on a synopsis of these empirical findings, we assume that a training period of several weeks with weekly training sessions of 90 min seems appropriate to the strategy’s complexity to ensure a minimum level of familiarity, and thus, the opportunity for the successful acquisition of procedural knowledge. This is also in line with findings from Ajaja [128] and Kinchin [58], who showed that greater familiarity with CM led to significant and consistent improvement in achievement. In agreement with Brandstädter et al. [22] who specifically address the method of instruction, we further assume that practical exercises in CM will be superior to purely theoretical teaching in terms of learning success. Finally, considering the learners’ activity and the degree of support, we assume that only guided training including step-by-step practicing makes the practical applicability of CM, as well as its benefits, clear to the learners, which, in turn, should motivate a later self-regulated use of the strategy [22,129].

1.4. Research Question and Hypotheses

Accordingly, one aim of our study is to answer the question of whether participants who receive a specific CM training are generally more successful in learning using CM than students who have been introduced to CM in another way.

Corresponding to this, we hypothesize that a respective CM training causes certain familiarity with the strategy, which, in turn, leads to:

- (1)

- More organization and elaboration processes during learning in terms of information integration into prior knowledge structures and thus knowledge consolidation.

- (2)

- Less perceived cognitive load during learning when using CM.

- (3)

- Better handling and editing prescribed and creating own concept maps, respectively.

2. Materials and Methods

Our quasi-experimental study was conducted over a six-week period and based on three experimental conditions, varying regarding the type and intensity of CM training. While the training phase dealt with the non-biological topic of intelligence, the learning and later test phases referred to the topic of cell biology, since we wanted to prevent test effects.

2.1. Sample

The recruitment of our sample (N = 73) from students at the University of Cologne (Germany) was carried out by offering the possibility of participating in an elective module to improve learning and using learning strategies successfully. The group assignment was based on self-selection for organizational reasons because the students needed to solve their everyday study program, too. Concretely, this means that interested students could choose one of three weekdays offered, in which they would each take part in our study during the following six weeks. Our resulting quasi-experimental design allowed for satisfactorily addressing our test conditions (see Section 3.1). The first group (T++, n = 27) received a CM training with scaffolding and feedback, the second group (T+, n = 21) received a CM training without scaffolding and feedback but only repeated practice, and the third group (T−, n = 25) received no special CM training but a short verbal instruction to its construction techniques. On average, the participants in our study were 22.6 years old, 78% were female, and 56% were enrolled in a natural science study program, whereas the others primarily studied a subject of humanities.

2.2. Experimental Design

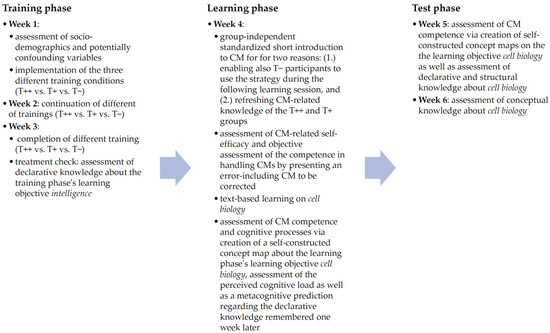

The procedure of our study was divided into three consecutive phases (training, learning, and testing), split into six weekly sessions: three training sessions, one learning session, and two test sessions, each on one day per week (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Timeline of the experimental procedure (T++ = CM training (n = 27), including additional scaffolding and feedback elements; T+ = CM training (n = 21), including no additional scaffolding and feedback elements; T− = control training (n = 25) including non-CM strategies).

The three experimental groups in our study varied in the intensity and content of support offered to participants during the CM training phase:

- (1)

- The first group (T++) was given additional scaffolding and feedback during CM practice and participants received a strictly guided training. First, the instructor gave an overview of the day’s learning objectives and main topics in terms of an advance organizer. An introduction to the CM strategy followed, including declarative knowledge elements about its practical use. A list of metacognitive prompts [41] (e.g., “Did I label all arrows clearly, concisely and correctly?” or “Where can I draw new connections?”; see Supplementary Materials Sections S2.3 and S2.4) was handed out for the individual work phase to induce the use of the relevant learning strategies of elaboration and organization [18], but prompts were reduced over the course of the training phase in terms of fading [130]. During the subsequent work phase, participants constructed concept maps based on learning text passages dealing with the abstract topic of intelligence. Here, they received different scaffolds (see Supplementary Materials Sections S2.1 and 2.2): in week 1, a skeleton map allowed participants to focus entirely on the main concepts and linking terms [80]; in week 2, a given set of the 12 main concepts taken from the learning material allowed participants to define links between these concepts on their own; and in week 3, T++-participants were able to construct concept maps completely by themselves. After each work phase, one of the participants’ completed maps was transferred to a blackboard and discussed. An expert map was presented and discussed as well, so participants were able to compare it to their own. Additionally, all participants received individual verbal as well as written feedback on their constructed concept maps. Considering previous findings [131,132,133], we decided on a knowledge of correct results (KCR) feedback approach but limited the feedback to marking CM errors and pointing out any resulting misconceptions. In addition, a list of the most common CM errors was available (see Supplementary Materials Sections S2.5 and S2.6).

- (2)

- The second group (T+) constructed concept maps in each session on their own without any additional support. As analyzing and providing feedback is very time-consuming, this approach is more economic and has been found to be effective as well [134]. The training sessions’ sequence was framed in almost the same manner as in group T++: all sessions started with an advance organizer, followed by an introduction to CM but without giving metacognitive prompts. During the subsequent individual work phase, participants worked on the same learning material but without any scaffolding during their own concept map construction. All participants had the opportunity to ask questions during the introduction but were not able to compare their own results to one of the participants’ or an expert map. Given these characteristics, this group represents the kind of practical training most likely found in classrooms [135,136].

- (3)

- The third group (T−) did not receive any CM training but used common non-CM learning strategies from other studies [18,114,137] to deal with the same learning material as the T++ and T+ groups: group discussions in week 1, writing a summary in week 2, and carousel workshops in week 3. The training sessions’ procedure was again framed in almost the same manner as in group T++: they started with an advance organizer, followed by an introduction to the respective learning strategy including metacognitive prompts (see Supplementary Materials Section S3). During the subsequent individual work phase, participants worked on the learning material and afterwards, they were given the opportunity to discuss their results and compare them to an expert solution.

2.3. Concept Map Scoring

There are many different scoring systems available for evaluating concept maps [138,139] due to their complexity and the implied hierarchical structure. To determine a CM score in our study, we applied two measures: On the one hand, we followed an approach from McClure et al. [140] assigning each proposition specified a value of 0 points (no relation between the concepts), 1 point (there is a relation between the concepts, but the arrow label is incorrect), 2 points (the arrow label is correct, but the arrow’s direction is not), or 3 points (the whole proposition is correct and meaningful). The combined score from all propositions specified by the participants was used as a learning success measure of the test phase, since participants who specify more propositions demonstrate their ability to build meaningful connections between a larger number of concepts. On the other hand, we developed an additional ratio score: the balanced Quality of Concept Map Index (bQCM Index), taking the quantitative performance aspect into account (the task was limited in time) as well: due to the trivial fact that the probability of making an error increases with a larger number of propositions specified, we put the concept map score as well as the numbers of technical and content-related CM errors into relation to the number of the participants’ overall propositions to provide a measure of training effectiveness. For the sake of clarity, the first-mentioned score following McClure et al.’s [140] approach, is called the absolute Quality of Concept Map Index (aQCM Index) below.

In addition, we also evaluated technical and content-related CM errors in the participants’ concept maps. The categorization of errors allows for assessing a person’s CM competence by focusing on the number of CM technical errors in relation to the overall number of propositions specified (concept map error ratio), and assessing a person’s understanding of the learning content by focusing on the number of content errors in relation to the overall number of propositions specified (content-related error ratio).

Other added measures to assess the quality of concept maps constructed by participants were the numbers of recall-suggesting (R-) propositions, organization-suggesting (O-) propositions, and elaboration-suggesting (E-) propositions (see Section 1.1, Section 2.4.4, and Section 3.4).

2.4. Further Measures and Operationalizations

In the following, we describe the operationalizations of the other dependent variables as well as those, we controlled for prior to the training. Their presentation is not based on the order of the hypotheses, but on the chronology of the study’s phases.

2.4.1. Measures Prior to Training Phase (Week 1)

To ensure the best comparability of our three groups (T++, T+, and T−), we first assessed the participants’ demographics (gender, age, etc.) and other relevant variables we wanted to control for, such as familiarity with CM, prior knowledge in biology, or reading comprehension (see Supplementary Materials Section S1).

As the quality of students’ learning is strongly determined by their prior knowledge [117], we assessed our participants’ prior knowledge regarding the learning phase’s learning objective of cell biology using an 18-item test, comprising established item sets from previous studies [141,142,143] which were partly adapted. After 3 of these 18 items were excluded from the subsequent analysis due to lack of reliability, the test showed an internal consistency of α = 0.74 for the present sample.

In addition, the participants were asked about the extent of their biology education during the last two years of schooling: no biology vs. basic biology vs. advanced biology (the only possible options regarding the German school system).

To assess the participants’ familiarity with concept maps, a seven-item scale from McClure et al. [140] was used and the following adaptions made: The answer-format (“yes” or “no”) was replaced by a 5-point rating scale (1 = never/very rarely to 5 = very often/always), the prior use of concept maps in school was assessed with the first question instead of asking whether the participant had never used concept maps, and the benefit of concept maps when solving problems was specified (see Supplementary Materials Section S1.3). The internal consistency of this set was α = 0.89.

As the topics and contents of the learning texts provided in the training (learning objective: intelligence) and the learning phase (learning objective: cell biology) were considered sophisticated, but had to be read in a given timeframe, the participants’ reading speed and comprehension were additionally assessed via the Lesegeschwindigkeits- und Verständnistest 6-12 (LGVT 6-12) [144]. In this test, participants are given four minutes to read as much as possible of a story about a woman trying to plant brussels sprouts herself. The text includes multiple sentences which are interrupted through brackets and the reader is instructed to mark the correct word out of three options in these brackets to continue the story in a meaningful way. The LGVT’s internal consistency was α = 0.67 for the present sample.

2.4.2. Measures after Training Phase/Treatment Check (Week 3)

After all participants had completed their respective training conditions on the learning objective intelligence, they were presented a self-designed multiple-choice test (20 items; α = 0.75) to assess their declarative knowledge about this topic (see Supplementary Materials Section S4). The respective results (see Section 3.2) were used to check for immediate effects of the three different training conditions and therefore served as a treatment check.

2.4.3. Measures Prior to Learning Phase (Week 4)

After this training phase, the participants of all three conditions received the same short introduction to the CM strategy at the beginning of week 4 to set comparable starting conditions regarding the subsequent learning phase: on the one hand, one week had passed since the training had ended; on the other hand, the T− group had not received any CM training yet. Immediately after this short introduction, the participants of all three groups were asked to fill in a questionnaire on their CM-related self-efficacy expectations (see Supplementary Materials Section S5). This assessment of the participants’ CM-related self-efficacy was used to quantify potential differences between the three different conditions since it could be expected that the T− group, which only received the short introduction, would rank their self-efficacy significantly lower. The chosen self-designed questionnaire (α = 0.88) consisted of six items (e.g., “I feel competent in choosing the important concepts for my concept map”), which were each rated on a 5-point scale (see Supplementary Materials Section S5).

Furthermore, they completed an error detection task by working on a prescribed concept map, including 18 propositions and some errors (e.g., missing arrowhead; see Supplementary Materials Section S6). The task was to detect and correct as many errors as possible out of a total of 10 in a given timeframe of four minutes. This task was implemented to obtain an additional objective measure of the competent use of the CM strategy beside the self-efficacy ratings. Here, a total of two measures was considered: (1) the quality of error detection and (2) the quality of error correction.

2.4.4. Measures during Learning Phase (Week 4)

Participants’ concept maps constructed during the learning phase on the topic of cell biology were evaluated following the bQCM Index procedure (see Section 2.3). To ensure evaluation objectivity in terms of interrater reliability, all participants’ concept maps were separately coded by two researchers, following recommendations by Wirtz and Caspar [145]. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and its 95% confidence interval were interpreted using Koo and Li’s [146] guidelines. The analysis yielded excellent interrater reliability (ICC = 0.90, CI95% [0.56, 0.96]) on average, indicating that participants’ concept maps can be clearly judged using the coding scheme of scoring.

In addition, the participants’ concept maps were analyzed with regard to the complexity of specified propositions, serving as an indicator of cognitive processes during learning. To that, we analyzed (1) how many relations were taken directly from the text (recall-suggesting [R-] propositions); (2) how many relations, that were not explicitly named in the text, were constructed between concepts of the text (organization-suggesting [O-] propositions); and (3) how many relations were constructed between a concept in the text and a concept that was not named in the text (elaboration-suggesting [E-] propositions). While a specification of R- and O-propositions can be accomplished with the text, the specification of E-propositions required an integration of prior knowledge elements into the concept map.

The participants’ perceived cognitive load during CM was assessed using the Cognitive Load Questionnaire (CLT) by Klepsch et al. [96]. The scale comprises seven items (α = 0.69) which refer to three distinguishable aspects of cognitive load: (1) intrinsic cognitive load (ICL, α = 0.62) results from demands made by the learning task itself; (2) germane cognitive load (GCL, α = 0.72) is related to the mental monitoring of learning and strategy use; and (3) extraneous cognitive load (ECL, α = 0.68) is not directly linked to learning since it only raises if ill-designed learning material/instruction claims additional mental resources. The CLT’s items were adapted by replacing the phrase “this task” with “constructing the concept map” as well as referring to the presentation of information in the text instead of the task itself in the second ECL-related question (see Supplementary Materials Section S8). All statements that had to be rated on a 7-point scale (1 = I do not agree at all to 7 = I agree completely).

Finally, in accordance with Karpicke and Blunt [147] and Blunt and Karpicke [148], participants gave metacognitive predictions in terms of a judgment of learning (“How much of the information from the text you will remember in one week from 0 to 100%?”). As CM can be a useful metacognitive learning tool [34,149], these metacognitive judgments were used to examine possible differences between participants’ self-predicted performance on questions concerning the topic of cell biology and their factual declarative knowledge assessed one week later (see Section 2.4.5).

2.4.5. Measures after Learning Phase/Learning Outcome (Weeks 5 and 6)

Concerning the three groups’ learning outcomes, we conducted several measures in a test phase that took place on two days within two consecutive weeks, covering CM competence as well as three different domains of knowledge: declarative, structural, and conceptual knowledge. While declarative knowledge consists of segregated information and facts, structural knowledge focuses more on contextual characteristics such as the relationships between these individual pieces of information and facts. Finally, conceptual knowledge categorizes the features and principles inherent in the data, facts, and relations in a highly decontextualized manner, so a learner becomes able to use his or her knowledge flexibly in various contexts [150,151,152,153,154].

During the first test session (week 5, 3-h testing), participants were first asked to create a concept map within 60 min using a given set of 22 concepts from the learning text on the topic of cell biology from the learning phase one week before. Concept map evaluation followed the aQCM Index procedure for measuring learning success and the bQCM Index procedure for measuring CM quality (see Section 2.3). As in the week before, all concept maps were separately coded by two researchers to assess interrater reliability [145]. The analysis yielded excellent objectivity as well (ICC = 0.93, CI95% [0.88, 0.96]) [146].

After the concept map was created, a 30-min Similarity Judgments Test (SJT) [155] was carried out to assess the participants’ structural knowledge about cell biology. Within this 55-item test, the semantic proximity of two given cell biological concepts (e.g., nucleus–bio membrane or ribosome–DNA) had to be rated on a 9-point scale (1 = minimally related to 9 = strongly related). A total of 11 central cell biological concepts was used, which were presented in a balanced manner. To prevent confounding sequence effects, two test versions were used, in which the sequence of the 55 pairs of terms was varied randomly (see Supplementary Materials Section S9). The SJT was first given to a sample of seven experts. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) regarding the experts’ ratings indicates excellent interrater reliability [146] (ICC = 0.95, CI95% [0.93, 0.97]), so face validity of the procedure can be assumed. The mean of the experts’ ratings on each item was used as an evaluation standard and the correlation of the participants’ responses with those of the experts was finally used as the measure of the participants’ structural knowledge (see Section 3.7).

At the end of this first test session, the participants completed a 60-min test on their declarative knowledge about cell biology. This self-designed multiple-choice questionnaire (see Supplementary Materials Section S10) comprised a total of 30 items (e.g., “Which of the following statements about the cell wall are correct?”). After two of these 30 items were excluded from the subsequent analysis due to lack of reliability, the test showed an internal consistency of α = 0.80.

During the second test session (week 6, 90-min testing), the participants’ conceptual knowledge about cell biology was assessed. For this purpose, a self-designed test (α = 0.79) with 15 open-answer items was used (see Supplementary Materials Section S11). An example of an item is: “The intake of poison from the destroying angel mushroom (α-Amanitin) leads to inhibition of the enzyme RNA-Polymerase II, which is responsible for the synthesis of an mRNA-copy of DNA information. Which consequences for protein synthesis as well as for the entire cell could be expected? Justify your answer.” Answers were coded as wrong (0 points), partially correct (1 point), or correct (2 points).

2.5. Materials and Procedure

In the training phase, our participants worked on a learning text on the topic of intelligence, whereas the learning material in the following learning phase belonged to the topic of cell biology. The text Theories and Models of Intelligence comprised 3197 words (8 pages) and was divided into three parts according to the three training sessions. The text The Structure and Function of Eukaryotic Cells comprised 2010 words (7 pages; see Supplementary Materials Section S7) and was used in the learning phase. Regarding the ecological validity, both the subject and content of these texts were rated by experts as adequate for learning at the university level prior to the study. In this manner, consistency, comprehensibility, and stringent reasoning were ensured as well.

In order to minimize Rosenthal/Pygmalion effects, a maximum standard of behavior and situation, which was fixed in writing and secured via a second investigator, was developed, which was strictly implemented in all study-related interactions with the participants.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

The collected data were analyzed using parametric and non-parametric procedures to detect potential group differences and relevant correlations. As appropriate, we further applied post hoc procedures to provide further information on the quantity and direction of group differences concerning single dependent variables.

3. Results

Below, we report our results of the statistical analyses based on the data of our N = 73 participants. Herein, we orient towards the chronological order of events, i.e., the point of measurement of the respective dependent variables during the study period.

3.1. Pre-Analyses of Baseline Differences (Measures Prior to Training Phase, Week 1)

To check whether there were significant baseline differences on relevant variables between the three training groups, we carried out difference testing for both categorial (χ²-test; see Table 1) and metric variables (univariate ANOVA; see Table 2). The results of the χ²-test indicate an equal distribution regarding the participants’ gender and university study program across the three groups. Regarding participation in biology courses during the last two years of schooling, however, there was a significant group difference, χ²(4) = 11.96, p < 0.05 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of cross-table analyses regarding possible baseline differences between the three groups.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and results of ANOVA regarding possible baseline differences between the three groups.

The results of the univariate ANOVA indicate an equal distribution across the three groups for all variables. The participants in the three conditions neither differ regarding their age or final school exam grade nor regarding their prior knowledge about cell biology, their familiarity with CM, or their reading competencies (see Table 2).

Overall, the results of our pre-analyses show no significant group differences regarding potentially confounding variables. We consider the statistically significant group difference concerning participation in biology classes during the last two years of schooling (see Table 1) to be irrelevant since the groups did not differ significantly in their prior knowledge about cell biology (see Table 2) and are therefore comparable to each other in terms of the dependent variables relevant to us. Accordingly, no covariates were additionally included in subsequent difference-testing analyses.

3.2. Treatment Check (Measure after Training Phase, Week 3)

After participants had completed the three training sessions working on the topic of intelligence, we assessed their declarative knowledge about this learning objective to evaluate the immediate effect of the three different training conditions (see Section 2.4.2). A univariate ANOVA showed that the three groups did not differ in their knowledge immediately after training, F(2, 70) = 0.08, p = 0.92, indicating that potential effects of the training conditions on knowledge acquisition do not seem to occur without any time delay.

3.3. Concept Mapping-Related Self-Efficacy and Error Detection Task (Measures Prior to Learning Phase, Week 4)

Regarding the participants’ CM-related self-efficacy, we expected that the two groups who received a CM training would feel more competent in handling concept maps than the T− group without such a training (see Section 2.4.3). Contrary to this expectation, the T− group rated its CM-related self-efficacy highest. However, the Kruskal–Wallis test did not indicate any statistically significant difference between the three groups, χ²(2) = 2,75, p = 0.25 (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and results of ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests regarding group differences in CM-related self-efficacy and the error correction task performance.

As part of the error detection task (see Section 2.4.3), participants should detect and correct as many errors as possible out of a total of 10 errors in a prescribed concept map with 18 specified propositions. In total, two measures were considered, (1) the quality of error detection and (2) the quality of error correction. Regarding the first measure (error detection) a comparison of the participants’ performance showed that the T++ group performed slightly better than the groups T+ and T−. However, these differences are not statistically significant, indicating that the CM training had no significant effect on the error detection rate. Regarding the second measure (error correction), a comparison indicates a significant group difference in the mean number of properly corrected errors, χ²(2) = 6.10, p < 0.05 (see Table 3). Post hoc pairwise comparisons showed that this significance is particularly based on the difference between the groups T++ and T− (z = 2.34, p < 0.05). The differences between the groups T++ and T+ (z = 1.82, p = 0.07) and between the groups T+ and T− turned out to be insignificant (z = 0.24, p = 0.81). Regarding a second aspect of error correction quality, analyses showed mean differences, suggesting that the T− group made a correct proposition incorrect and/or recognized a CM error but were unable to correct it properly and therefore only replaced one error with another. However, these differences proved to be insignificant by a Kruskal–Wallis test, so the number of improperly corrected errors seems largely unaffected by the CM training (see Table 3).

3.4. Recall, Organization, and Elaboration Processes (Measures during Learning Phase, Week 4)

Within our hypotheses, we further assumed that CM training would have a positive effect on organization and elaboration processes during CM (see Section 1.4), operationalized by the number of recall-suggesting (R-) propositions, organization-suggesting (O-) propositions, and elaboration-suggesting (E-) propositions specified. Group comparisons, however, show no significant mean differences between the three groups regarding the extent to which different classes of propositions are specified (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and results of ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests regarding different types of specified propositions.

3.5. Cognitive Load (Measures during Learning Phase, Week 4)

Regarding the participants’ cognitive load, we assumed that greater familiarity with the CM strategy would reduce the perceived cognitive load during CM (see Section 1.4). The mean values for the three distinguishable facets of cognitive load are presented in Table 5. With regard to the dimension of extraneous cognitive load (ECL), a comparison indicates a significant group difference, χ²(2) = 6.51, p < 0.05 (see Table 5). Post hoc pairwise comparisons showed that this significance is particularly based on the difference between the groups T+ and T− (z = −2.54, p < 0.05). The differences between the groups T++ and T+ (z = 1.18, p = 0.72) and between the groups T++ and T− turned out to be insignificant (z = −1.47, p = 0.42). Regarding the two other dimensions of cognitive load, the results of the Kruskal–Wallis tests showed no statistically significant differences between the three groups (see Table 5). Altogether, these results indicate that participants from the T− group regarded the learning material more taxing (ECL) than the T+ group but all groups regarded the CM task itself equally complex (ICL), were equally engaged, and directed their mental resources to learning processes (GCL) to a very similar extent.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics and results of and Kruskal–Wallis tests regarding the facets of perceived cognitive load.

3.6. Metacognitve Prediction (Measures during Learning Phase, Week 4)

Analyses of the participants’ judgments of learning (metacognitive predictions on how much they would remember after one week) assessed at the end of the learning phase also yielded no significant differences between the groups, F(2, 70) = 1.82, p = 0.17, indicating that the training did not influence the participants’ metacognitive prediction. Numerically, group T+ predicted the highest learning retention (M = 58.1, SD = 21.12), followed by group T++ (M = 50.74, SD = 28.14), and T− (M = 44.4, SD = 24.51). However, beyond that, correlational analyses show significant relationships between these judgments of learning and the aQCM Index (indicating overall concept map quality) as well as the scores for declarative and structural knowledge (SJT) of the later test phase, indicating that the participants’ judgments of learning were quite accurate across all groups (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlations between the judgments of learning and factual later learning outcome.

3.7. Concept Map Quality, Structural, Declarative, and Conceptual Knowledge (Measures after Learning Phase/Learning Outcome in Test Phase, Weeks 5 and 6)

With regard to the participants’ learning outcomes, we stated that CM training would facilitate learning using CM, and thus, would cause better overall learning success (see Section 1.4). This learning outcome was assessed by evaluating the concept maps constructed by the participants using the aQCM Index, and the achieved scores in tests of structural, declarative, as well as conceptual knowledge about the learning objective of cell biology. The MANOVA carried out indicated significant overall group differences in terms of learning success F(8, 134) = 3.36, p < 0.01, η² = 0.17. A post hoc univariate ANOVA shows that the significant group differences belong to the dependent variables concept map quality (aQCM Index), structural (SJT score), and conceptual knowledge, whereas the dependent variable declarative knowledge only shows a clear, albeit statistically insignificant, difference. Corresponding post hoc pairwise comparisons indicate that the significant differences are largely attributable to the differences between the T− group and the two training groups T++ and T+ (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics and results of ANOVA and post hoc tests regarding the content-related learning outcome.

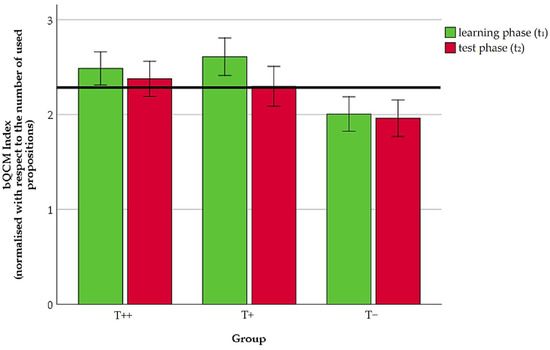

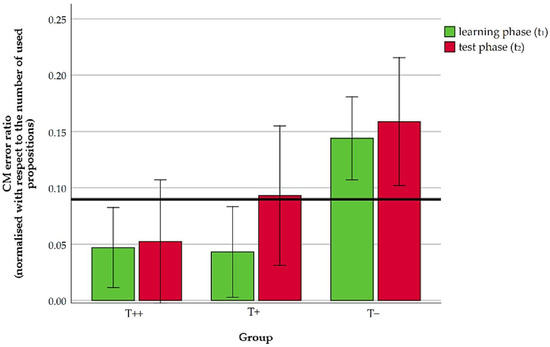

In addition to this analysis of group differences, it seemed expedient to analyze the learning development of our participants between learning and test phase in terms of a training-related advantage in concept map quality. Within the corresponding repeated measure ANOVA, we considered the CM’s quality (bQCM Index; see Section 2.3) as well as the proportional frequency of technical errors (concept map error ratio; see Section 2.3) as dependent variables. However, there was no statistically significant interaction effect between the three groups and the point of measurement (POM) on these two variables (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics and results of repeated measure ANOVA regarding concept map quality over time within the different groups.

Although the repeated measures analysis turned not out to be significant for the interaction effect across all groups, post hoc tests to check for individual differences were carried out considering inequality of variances. For both dependent variables, it turned out that the group T− differed significantly from both training groups (T++ and T+), whereas there were no significant differences between these two training groups (see Table 9; Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Table 9.

Post hoc test results for the interaction effect group × time.

Figure 3.

Bar chart representing intragroup changes in bQCM Index between the learning phase in week 4 and the test phase in week 5 (T++ = CM training (n = 27), including additional scaffolding and feedback elements; T+ = CM training (n = 21), including no additional scaffolding and feedback elements; T− = control training (n = 25) including non-CM strategies; error bars are based on standard error of mean; the overall mean value is represented by the bold line in black).

Figure 4.

Bar chart representing intragroup changes in CM error ratio between the learning phase in week 4 and the test phase in week 5 (T++ = CM training (n = 27), including additional scaffolding and feedback elements; T+ = CM training (n = 21), including no additional scaffolding and feedback elements; T− = control training (n = 25) including non-CM strategies; error bars are based on standard error of mean; the overall mean value is represented by the bold line in black).

Taking a closer look at the differences within groups between the two POMs, the bQCM Index shows that the performance of the groups T++ and T− did not change significantly over time, while the T+ participants performed significantly different at the two POMs, t(20) = 2.96, p < 0.01, dCohen = 0.69. Regarding the concept map error ratio, the merely numerical values of the T+ participants’ performance seemed to differ between the two POMs as well, but a Wilcoxon test showed this difference to be statistically insignificant, z = −1.71, p = 0.09, n = 21. The performance of the groups T++ and T‒, on the other hand, did neither change visibly nor statistically significantly over time (see Figure 3 and Figure 4). These results overall indicate that, for the T+ group, the CM-related performance (operationalized via bQCM Index and concept map error ratio) in the later test phase was at a significantly lower level than in the learning phase one week before.

4. Discussion

We hypothesized that an extensive CM training makes learning with CM more effective in terms of more organizational and elaborative information processing, less perceived cognitive load, and better overall learning success (see Section 1.4). Considering our statistical analyses, this assumption, which is in line with theoretical considerations and empirical findings, is partially supported by our results.

4.1. Pre-Analyses of Baseline Differences (Measures Prior to Training Phase, Week 1)

To ensure valid conclusions from our results, we first checked for a balanced distribution of relevant sample characteristics. Our results showed comparability of the three groups in terms of age, sex, final overall school exam grade, and course of study at the university as well as prior knowledge about cell biology, even though the group assignment was based on self-selection for organizational reasons. Altogether, this allows for stating participants’ equal initial conditions.

4.2. Treatment Check (Measure after Training Phase, Week 3)

To evaluate an immediate effect of the three different training conditions, we assessed the participants’ declarative knowledge about the learning objective of intelligence after the training sessions, which, however, did not differ significantly between the three groups (see Section 2.4.2 and Section 3.2). Neither an extensive CM training nor the corresponding conditions had an impact on the immediate (no delay) retention/reproduction performance of our participants. One the one hand, this result could indicate, that training success is only assessable after a specific time delay. One the other hand, this result could also indicate that the acquisition of knowledge about the topic of intelligence probably took place in an intuitive way common to all students, in which they are accustomed to learning. Additionally, it is noticeable that neither CM nor the training method caused any interference in terms of additional (cognitive) burdens for short-term learning and reproduction.

4.3. Concept Mapping-Related Self-Efficacy and Error Detection Task (Measures Prior to Learning Phase, Week 4)

On the first day of the learning phase, participants in all three groups received the same 30-min short introduction to the CM strategy for two reasons: (1) to enable T− participants to use the strategy during the following learning session, since they had not received any training on CM yet, and (2) to refresh CM-related knowledge of the other two groups T++ and T+. Immediately afterwards, all participants were asked to judge their CM-related self-efficacy expectations and to solve an error detection and correction task using a prescribed error-including concept map (see Section 2.4.3).

The CM training had no significant effect on the error detection rate, while only the T++ group showed significant advantages over the groups T+ and T− when correcting errors. Furthermore, the T− group tended to correct errors more falsely compared to the training groups. The fact that the participants of all three groups achieved comparable results regarding the error detection rate could be due to the fact that the task we used for its assessment and especially the presented error characteristics were not difficult enough to differentiate between groups. A more complex test, also including content-related errors next to formal ones, would probably have led to clearer results.

Furthermore, we had expected that the two CM training groups (T++ and T+) would report higher levels of CM-related self-efficacy expectations than participants in the T− group. Surprisingly, the opposite was found. The T− group reported a slightly higher (although not significantly different) self-efficacy expectation than the two training groups, and the self-efficacy expectation in the T++ group was the lowest (see Table 3). Based on our pretests, we assume consistent comparability of our three groups, also with regard to their level of accuracy in metacognitive prediction (see Section 3.6) as well as their cognitive load (see Section 3.5). Therefore, both findings can be attributed to sample characteristics, since our student participants were experienced in learning and in adapting new learning strategies in different settings. It is therefore conceivable all participants generally had a high level of trust in their academic abilities and were therefore equally confident that they will be able to cope with using the CM strategy successfully. On the other hand, if the merely numerical differences regarding CM-related self-efficacy are taken seriously, it is reasonable to assume that the two groups T++ and T+ were already more familiar with the complexity of the CM strategy and, therefore, were less confident than participants of the T−group, who possibly put CM on the same level with less complex mind maps they might be familiar with, and thus, underestimated the actual requirements.

4.4. Recall, Organization, and Elaboration Processes (Measures during Learning Phase, Week 4)

Contrary to our hypothesis that an extensive CM training would have a positive effect on organization and elaboration processes during CM (see Section 1.4), our analysis did not reveal any substantial group differences in this regard. However, our results show that participants in all three groups achieved comparably good results, especially regarding the number of recall-suggesting propositions they specified within their concept maps (see Table 4). Similarly to the case of CM-related self-efficacy expectations, this result could be plausibly attributed to specific characteristics of our student sample, including solely experienced learner who perform comparably well. Furthermore, the learning texts on intelligence and cell biology were comparable to learning and study material on a university level in terms of formal as well as educational characteristics. Students who are skilled in conceptual and contextual learning will therefore probably only show random differences in making and keeping terms available, which are simply to be reproduced in a concept map. The construction of O- and E-propositions, requiring skills beyond simple reproduction, was only achieved at a comparatively marginal level by all participants, unassociated with any significant group differences. If it is also taken into account that the concept of learning implies a developmental characteristic, the question arises when and under which conditions meaningful learning associated with organization and elaboration can be expected to be successful. In the context of our study, it can be plausibly assumed that it might have been too early to expect such performance from our participants. The problem can also be seen in a rather traditional way in terms of a reminder for teachers that learners must be picked up where they are [156]. Post hoc, it is not possible to decide whether our participants could have been overwhelmed by a corresponding task since they had not explicitly been given this task (to carry out specific cognitive processes during learning). Nevertheless, a further testable hypothesis would have to consider that, when introducing and using CM as a learning strategy, it could be crucial to make the respective learning and above all competence goals explicit and to prepare them theoretically and procedurally. In this way, the learners’ support could be focused on all opportunities related to CM that go beyond a simple reproduction of what has been learned and which is also discussed as scientific literacy [157,158,159,160,161,162].

4.5. Cognitive Load (Measures during Learning Phase, Week 4)

Contrary to our hypothesis that training-related familiarity with the CM learning strategy differentially reduces the perceived cognitive load during the creation of a concept map (see Section 1.2 and Section 1.4), our analyses only revealed a substantial group difference regarding extraneous cognitive load (ECL), while the reported intrinsic (ICL) and germane cognitive load (GCL) did not statistically differ between the three groups (see Table 5). A higher ECL usually indicates a learning material’s influence on participants’ cognitive load. However, as all groups worked on the same learning material and, beyond that, the internal consistencies of the ECL and the ICL scales, were questionable, a significant difference or the lack of it should not be overestimated (see Section 2.4.4 and Section 4.8). Beyond that, the 30-min short introduction was probably sufficient enough to undermine a differentiating influence of a special training (see Section 4.2 and Section 4.3), if it is again taken into account that our sample consisted of experienced learners.

4.6. Facilitated Acquirement of Knowledge and Skills (Measures during as Well as after Learning Phase, Weeks 4, 5, and 6)

The central hypothesis of our study focused on the supportive effect of CM training on overall learning success (see Section 1.3 and Section 1.4). We experimentally chose the concept map quality as well as structural, declarative, and conceptual knowledge as indicators of learning success. For the domain of declarative knowledge, our results show effects by trend. Regarding the other three measures, we found clear and global effects of the training on the participants’ performance. Significant advantages of the T++ group over the T− group occur regarding all relevant post hoc comparisons (with the exception of the declarative knowledge scores), which demonstrates that an extensive training including scaffolding and feedback elements is clearly more effective than a short introduction (see Table 7). In addition, the differences in structural (SJT score), declarative, and conceptual knowledge between the two training groups T++ and T+ were insignificant and only offer some trends regarding concept map quality (aQCM Index). Considering this, it could be argued that a CM training could also be implemented with a focus on efficiency and thus less effort. However, this could be countered by the fact that the statistical insignificance of the assessed knowledge domains between the T++ and T+ groups can be related to a lack of clear requests to the participants of the T++ group to focus on the development of the specific knowledge represented by the aQCM Index or concept map quality during the test procedure. An investigation that addresses this requirement could contribute a crucial aspect to the learning-related functionality of CM. Above all, the significant decrease in CM-related performance of the T+ group from the learning to the test phase one week later should be considered in this regard (see Section 3.7 and Section 4.6.1).

4.6.1. Concept Map Quality

To determine concept map quality, the two dimensions bQCM Index and CM error rate of the learning and test phases were considered. An analysis of the learning development within the three groups regarding these two variables did not reveal any significant interaction effect but this result might be due to unequal variances between the groups. Accordingly, adjusted post hoc comparisons showed a clear advantage of the two training groups (T++ and T+) over the control group (T−), which contradicts the findings of Hay et al. [118], who stated that CM can be taught in a single session within 10–20 min. A comparison within the groups between the first and second POM showed a small decrease in performance except for a significant reduction of the bQCM Index and a tendency towards an increase of the concept map error rate in group T+ (see Table 9; Figure 3 and Figure 4). Looking closer at this finding and keeping in mind that the groups T++ and T+ do not significantly differ in terms of declarative, structural, and conceptual knowledge as well as concept map quality, it can be assumed that the CM-related knowledge advantage (bQCM Index and concept map error rate) of the T+ group, which it initially had in common with the T++ group compared to the T− group, was clearly lost again after just one week (see Table 9). How and when a stable CM competence can be expected from learners, therefore, seems to be a question about the interaction of training intensity, special training elements, and causal delay.

4.6.2. Structural Knowledge

The results on structural knowledge (SJT score) indicate a significant global difference between the three groups (see Table 7). Post hoc comparisons show that the two training groups (T++ and T+) performed almost identically, but both significantly better than the participants in the T− group. Thus, it seems plausible to suppose that an extensive CM training may facilitate the acquisition of knowledge about the relationsships bewteen central terms of a field when using CM, whereas a short 30-min introduction to CM seems to be insufficient in this respect.

4.6.3. Declarative Knowledge

For the domain of declarative knowledge, our results show only effects by trend. Although both CM training groups (T++ and T+) performed numerically better than the control group (T−), our analyses revealed no statistically significant group differences. Overall, the T+ group performed best. Accordingly, CM training could promote retention performance somewhat better than a short introduction (see Table 7). However, regarding all three groups performing equally badly, we may suppose that neither CM by itself nor a respective training significantly affects the acquisition of declarative knowledge.

4.6.4. Conceptual Knowledge

In terms of conceptual knowledge, our results indicate a significant global group difference (see Table 7). Post hoc comparisons reveal a comparable pattern of results as in the case of structural knowledge: While the two training groups (T++ and T+) performed almost identically, they each performed significantly better than the participants of the T− group. Accordingly, for the acquisition of conceptual knowledge, it can be assumed that familiarity with the CM strategy caused by training is a crucial and beneficial condition. Thus, a 30-min short introduction to the CM strategy seems insufficient to enable learners to effectively acquire conceptual knowledge using CM. When learning a topic/text, CM can make the learner aware of conceptual gaps. Incorrect relationships may have been recognized or learners realized that they were simply unable to integrate terms meaningfully into an existing structure. The supportive effect in the development of this metacognitive competence is an argument for the benefits of CM [163,164]. As part of a follow-up investigation, it would therefore be of interest to have a closer look at the question of which metacognitive skills are enhanced in which way by using CM, and which ones could have contributed to the advantages of our T++ group in particular.

4.6.5. Metacognitive Prediction

At the end of the learning phase on cell biology, we asked our participants to estimate how much of what they had just learned they would remember in the test phase one week later. This judgment of learning served as a measure of the participants’ confidence in the success of their efforts (see Section 4.6). Interestingly, our corresponding data analyses did not indicate any significant differences. It is plausible to assume that the accurate fitting of the participants’ skills to the experimentally realized requirements regarding the topic and the learning strategy did not allow for significant differences due to different training conditions as well as with regard to the judgment of learning. Regarding our student sample, we consider that the CM learning strategy simply represented an addition, which was apparently easy to assimilate for our participants to the already existing learning experiences and corresponding skills. This homogenizing factor, in addition to the used learning material which was comparable to the material they already were familiar with, could have undermined larger differences between groups regarding their metacognitive prediction.

4.7. Summarizing Discussion and Implications

CM is effective for learning and can also promote in-depth knowledge acquisition in terms of flexibly transferable knowledge [50,60,67,76,78]. Students can use CM as a learning strategy to visualize complex relationships by organizing and connecting central concepts with each other and probably with those out of their prior knowledge. For educators, CM represents a teaching format to summarize important content, and a diagnostic tool to assess students’ knowledge of a domain since concept map construction requires conceptual knowledge and its result reflects the quality of knowledge organization [80,113]. However, our results show that concept maps should only be used as a diagnostic tool if it has been trained adequately beforehand as the development of conceptual knowledge was positively influenced by CM training (see Table 7) when CM is used as a learning tool. In addition, practicing CM as a learning strategy must be preceded by a differential educational evaluation of learners and the topic as well as the learning material and objective.

Our findings, therefore, support those of studies by Ajaja [128], Kinchin [165] and Jegede et al. [110], who state that more experience in CM leads to significant and consistent improvement in achievement. In particular, the practical exercise elements during training seem to be decisive for the development of a high-level CM sills, as the participants in our T‒ group, who had only received a theoretical short introduction to CM, performed significantly worse in this respect. This finding is in line with those of Brandstädter et al. [22], Sumfleth et al. [69], Nesbit and Adesope [67], and Horton et al. [36]. The use of prompts and feedback in an extensive CM training has not been attempted before although has been proven to be effective in studies [66,120,166,167]. Our results show that the T+ group achieved as good performance in many cases as the T++ group, which additionally received time-consuming scaffolding and feedback, so it could be argued that a CM training could also be implemented with less effort, but in this respect, it should not be missed that there was a significant decrease in CM-related performance of the T+ group from the learning to the test phase just one week later (see Section 3.7 and Section 4.6.1). Finally, the extent of a specific training above a 30-min introduction showed no significant effect on the acquisition of declarative knowledge, but this result must be interpreted considering the characteristics and purpose of CM, since the strategy focuses more on acquisition of structural and conceptual knowledge.

4.8. Limitations

Even though our results provide substantial clarification, they need to be evaluated in light of the study’s limitations:

- (1)

- Regarding our student sample, we assume a high homogeneity in terms of a high degree of learning experience and academic performance. Therefore, it might be possible that the CM learning strategy was quite easy to assimilate for our participants to their already existing learning strategy repertoire. This homogenizing factor, in addition to the applied learning material, which was comparable to the material they already were familiar with, could have undermined some group differences on dependent variables regarding the three different training conditions. In this regard, it could be expected that referring to other samples than experienced learners could reveal more distinct group differences. Nevertheless, our total sample size of N = 73 was simply too small to draw conclusions in terms of external validity, so we recommend interpreting our results found for our small student sample size with caution.

- (2)

- Furthermore, the number of N = 73 participants in our study was not large enough to reach sufficient absolute frequency. Accordingly, a parallelization of the groups to which the participants had assigned themselves could not be achieved to our complete satisfaction, even if no initial differences could be shown. This is directly related to the power determined for our data analysis, which did not exceed about 0.30 for correlational and about 0.45 for ANOVA testing. To ensure that our expected small to medium-sized effects could be detected at a power level of 0.80 to 0.90, our sample should have included approximately N = 150 participants. Despite the desirability of such optimized test conditions, it seems difficult to imagine how the required intensive care of such a large number of participants could have been ensured over a six-week study period, given limited personnel and financial resources.

- (3)

- The instrument used to assess the participants’ ability to detect errors in a prescribed concept map (see Section 2.4.3 and Section 3.3) was apparently too easy for all three groups. A more complex test, presenting formal as well as content-related errors at different levels of difficulty, could have led to clearer results.

At least, we may take the liberty of noting that, once the limitations of our study are removed in future testing, we expect our trend-wise group differences to have a higher probability of becoming statistically significant.

4.9. Prospects for Future Research

On a general level, our study was able to replicate existing findings showing that CM is an effective learning tool [34,36,37,38,42,59,67,122]. Beyond that, our results indicate that the overall learning success can be improved by an extensive CM training and that stable CM strategy skills in particular can be promoted by additional integration of scaffolding and feedback elements in the course of such a training. However, the question of the interaction of training intensity, special training elements, and causal delay remains unanswered in our study, since our small sample size and the homogeneity of the participants do simply not allow for giving a specific reliable recommendation in this regard. Further investigations could therefore focus on answering this question first, since it would be helpful in terms of efficiency if it could be determined which specific components of a training are particularly effective in learning of different learners and to what extent.

In particular, the learner’s intrinsic motivation could be considered as a covariate in this regard, as it can be assumed that the learners’ potential is directly related to it [168,169], so it is conceivable that training effectiveness increases by intentionally stimulating motivational aspects. In this connection, it would also be of interest to have a closer look at the question of which metacognitive skills are enhanced in which way by using CM, and which ones could have contributed to the advantages of our T++ group in particular.