Evaluate the Feasibility of the Implementation of E-Assessment in Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) in Pharmacy Education from the Examiner’s Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Construction and Application of e-OSCE

2.2. OSCE Planning and Implementation

2.2.1. Description of Course

2.2.2. Implementation of EAS in OSCE

2.3. Examiner’s Acceptance Assessment of e-OSCE System

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

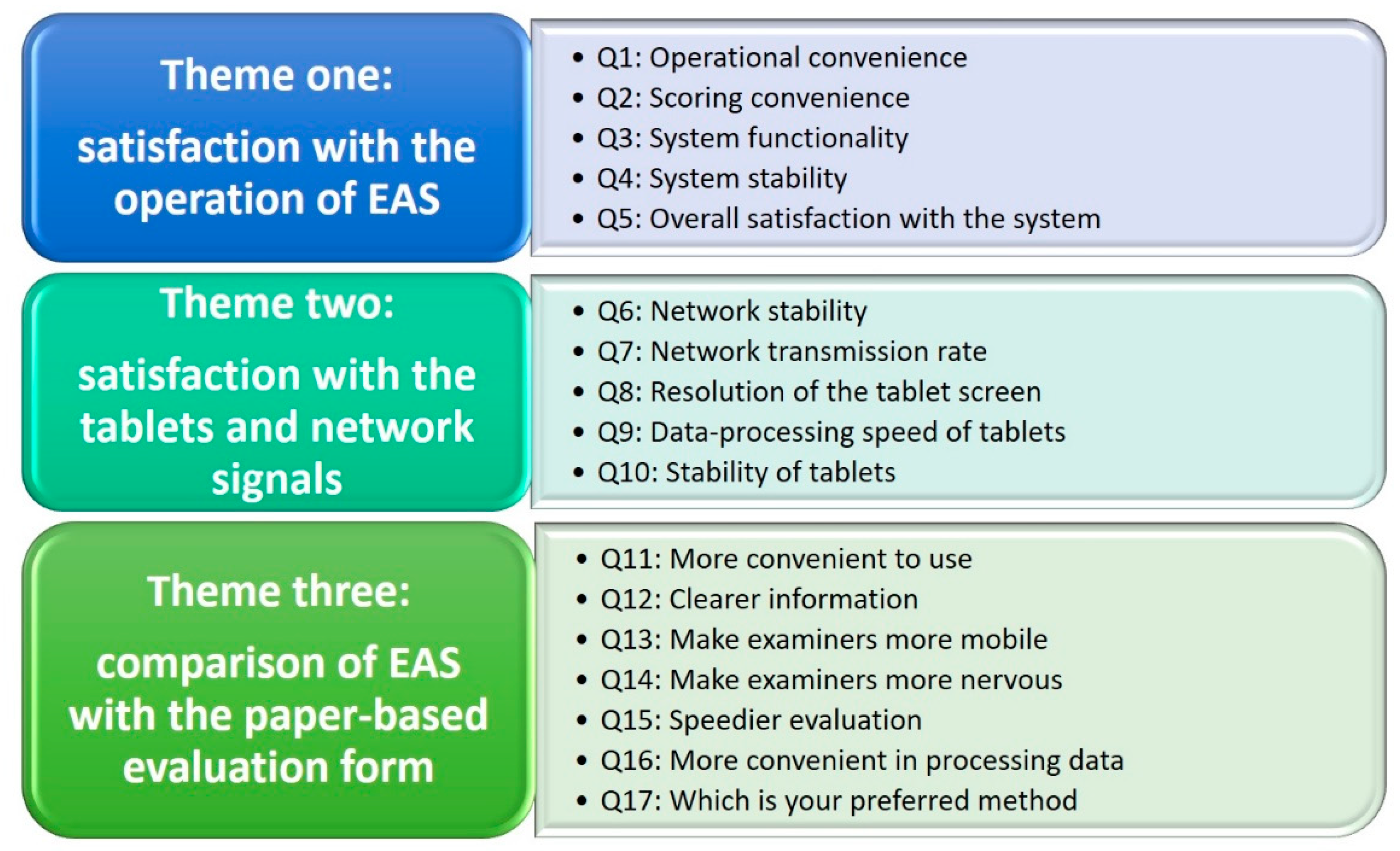

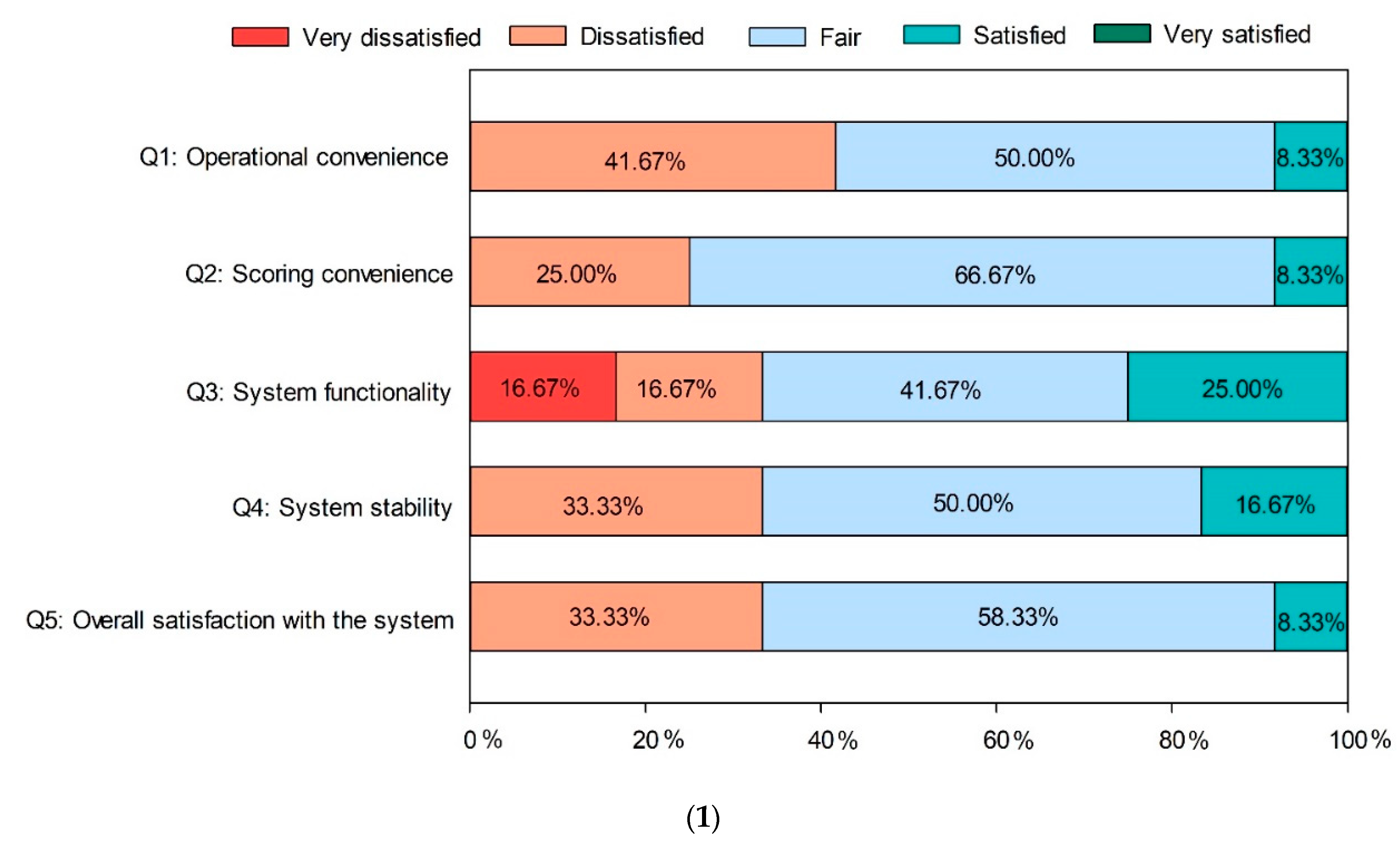

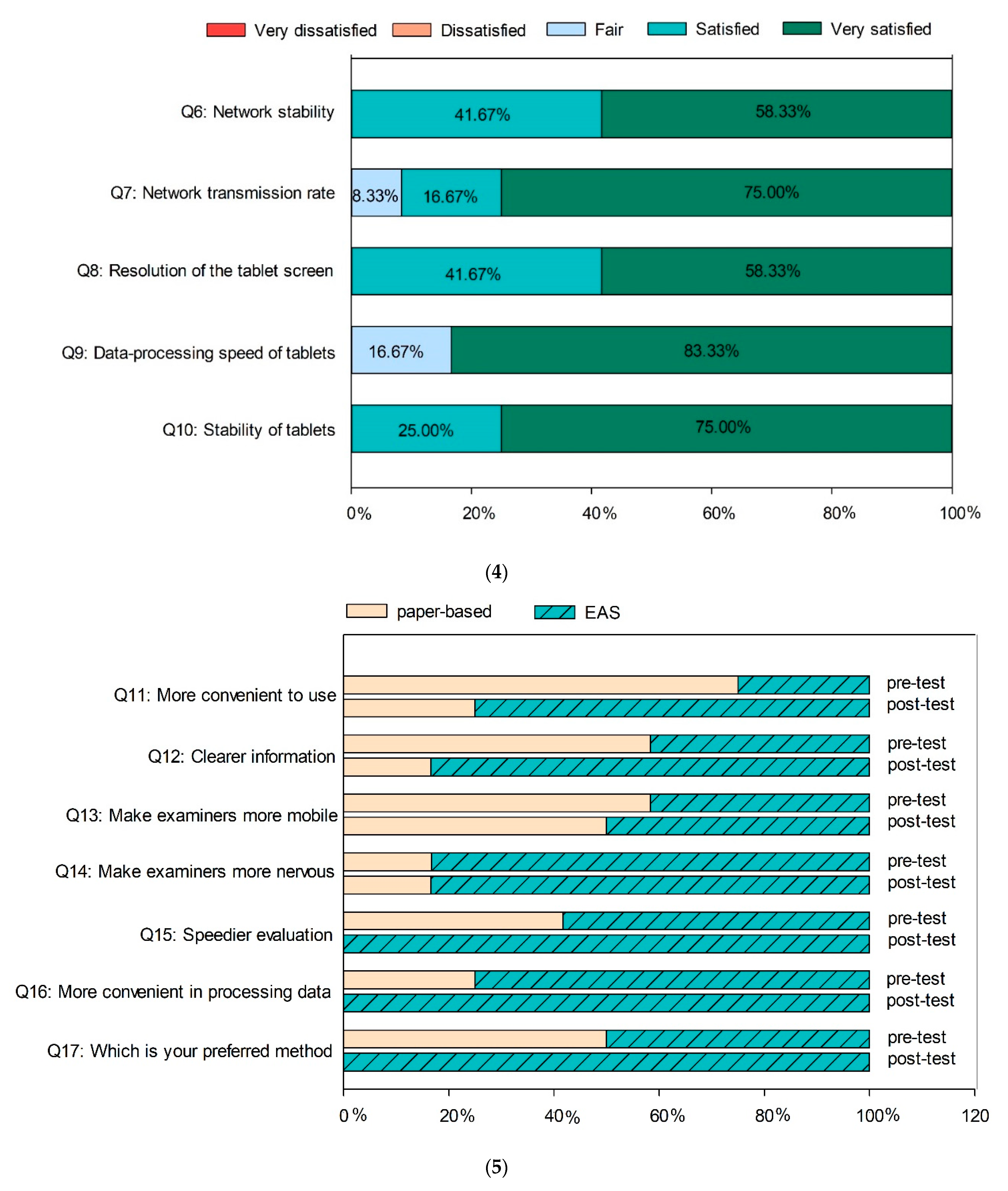

3.1. Results of the Examiners’ Satisfaction with EAS

3.2. Comments Relating to the Course Administrator with EAS

- Removes the potential for missing data: due to certain factors, such as the examiner falling asleep or losing focus [22], the item numbers are frequently left unmarked in traditional paper-based methods, leading to uncertainty regarding student performance on these items and inaccurate results. EAS helps to reduce errors in evaluation, as submission is allowed only when the electronic forms are fully complete. If examiners overlook an evaluation item, the evaluation data is not transferred and stored in the system. For paper-based assessment forms, problems with illegible handwriting from examiners often cause troubles for the administrators. EAS facilitates the storage and the analysis of assessment results as well as reduces the possibility of data loss [14].

- Instantly processes evaluation data and provides timely feedback to students: when paper assessment forms were used in the past, it was impossible to know instantly the total score and the overall performance of the students after the OSCE ended. Instead, the analyzed results could only be known after the data were integrated and calculated. The length of this process depended on the number of students taking the test. However, automatic scoring technology helped to make large-scale testing convenient and cost-effective [23]. A change from paper-based to computer-based assessment took place in many large-scale assessments [24]. Using e-assessment can reduce the teachers’ burden to assess a large student number [25]. For EAS, the evaluation data are instantly uploaded to the server-end for calculation and storage as the examiners carry out the evaluation. The administrators and the examiners are able to verify final scores quickly and efficiently. Besides, EAS analyzes the stored test results and collates these results into personal or overall performance reports for students, presenting them in diagrams for examiners to review, and to provide appropriate, timely feedback to students [14,26], enhancing the measurement of learner outcomes [24,27].

- Reduces waste of resources and provides good data preservation functions: the paper-based evaluation method generates a large number of written materials, such as evaluation forms. Electronic methods not only reduce the huge amounts of paper waste in the course of the tests, other features such as the saving of space in the preservation of relevant data, the fact that stored data are not easily damaged, and the convenience in filing and data search are also advantages that paper assessment forms are unable to achieve. Kropmans et al. estimated the e-assessment method may reduce costs by 70% compared to paper-based methods [28].

- Some studies indicated that using e-assessment saves the teacher or the staff time compared with paper-based assessments [23,29,30]. For administrators, although some time was required to input schedules and paper-based checklists into the EAS program, EAS was friendly and efficient to users. For the paper-based OSCE, the cumbersome preparation work for the test is a significant burden to organizers, such as preparation of various evaluation forms and arrangement of candidates’ examination stations and timetables, which usually takes 1 to 2 days. Further, the evaluation forms of each examiner have to be collected, collated, checked, and recorded after the test, which usually takes 3 to 6 days. It also causes even greater trouble if some scores happen to go missing or data become damaged or lost in the process. Compared with traditional paper-based methods, EAS requires less setup time before the test and less data processing time after the test. These tasks could be completed in about 1 day and 1 to 3 days, respectively. EAS reduces the overall workload of pre-test preparation and post-test data processing in administering a practical examination by approximately 40% to 50%, and this result is similar to a finding by Snodgrass [15].

- Potential technical problems: additional contingency planning must be implemented to resolve potential technical problems that could occur, such as battery life [7]. The day before the exam, the tablets must be checked in advance to ensure tablets are fully charged and that the tablet charging stations are placed at each OSCE station. This may increase the workload of administrators. In order to prevent unpredictable failure of the tablet, a few paper copies of the marking checklists can be placed at each OSCE station to be used in the event of technical problems with EAS.

- Technical issues inherent in using new technology: for administrators who have never used this system, it takes time to learn and to familiarize themselves with the operation of the system, which increases the time to establish the initial EAS. Problems for the examiner include technical problems encountered when logging in, trouble selecting and deselecting items due to unfamiliarity with the tablets touch screen, or holding the weight of the tablets throughout the examining, which makes the examiners more obviously fatigued.

- For a longer checklist, the examiner needs to scroll through the longer list to grade student performance. Although it was reported that scrolling through the iPad checklists was easier than searching through pages of paper-based checklists [13], some examiners in this study stated in their feedback that, since the order in which students answered the grading items varied, scrolling through a longer list to find examinees’ answer items affected the simplicity of the scoring. On the other hand, some examiners noted that the noise caused by searching through pages of paper-based checklists made examinees nervous, while scrolling through the tablet checklists does not cause a similar problem.

3.3. Comments Relating to Examiners with EAS

- Convenient to use: the functions were clear and simple to click. After practice, the examiners became familiar with the operation and scored smoothly.

- High calculation efficiency: when the examiners clicked to submit the results, the results were calculated instantaneously.

- Fonts that can be enlarged: the fonts on paper evaluation forms were small, making it difficult for the examiners to mark, with the possibility of ticking the wrong items. The fonts in EAS could be enlarged with flexibility whenever necessary, making it more convenient for the examiners to mark the checkbox.

- Completeness of the score: it is likely for examiners to overlook marking certain checkboxes in the paper-based checklist. EAS has the function where “results cannot be sent when the evaluation is incomplete”, which helps examiners to ensure the completeness of the evaluation and prevents affecting the score of the students.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grover, A.B.; Mehta, B.H.; Rodis, J.L.; Casper, K.A.; Wexler, R.K. Evaluation of pharmacy faculty knowledge and perceptions of the patient-centered medical home within pharmacy education. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2014, 6, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, W.J.; Kristi, W.K.; Dana, P.H.; Stuart, T.H.; Karen, F.M. Addressing competencies for the future in the professional curriculum. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2009, 73, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, C. An assessment of students’ performance and satisfaction with an OSCE early in an undergraduate pharmacy curriculum. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2014, 6, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, Z.; Ensom, M.H. Education of pharmacists in Canada. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2008, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, B.; Moore, K. The mini Clinical Evaluation Exercise (mini-CEX) in a pre-registration osteopathy program: Exploring aspects of its validity. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2016, 19, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hassanpour, N.; Chen, R.; Baikpour, M.; Moghimi, S. Video observation of procedural skills for assessment of trabeculectomy performed by residents. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2016, 28, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, A.; Minshew, L.M.; Anksorus, H.N.; McLaughlin, J.E. Remote OSCE experience: What first year pharmacy students liked, learned, and suggested for future implementations. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harden, R.M.; Stevenson, M.; Downie, W.W.; Wilson, G.M. Assessment of clinical competence using objective structured examination. Br. Med. J. 1975, 1, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baid, H. The objective structured clinical examination within intensive care nursing education. Nurs. Crit. Care 2011, 16, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznick, R.K.; Blackmore, D.; Dauphinee, W.D.; Rothman, A.I.; Smee, S. Large-scale high-stakes testing with an OSCE. Acad. Med. 1996, 71, S19–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, G.R.; Suhoyo, Y.; Nurhidayah, R.; Hasdianda, M.A.; Dewi, S.P.; Chaniago, Y.; Wikaningrum, R.; Hariyanto, T.; Wonodirekso, S.; Achmad, T. Large-scale multi-site OSCEs for national competency examination of medical doctors in Indonesia. Med. Teach. 2016, 38, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Lee, F.Y.; Hsu, H.C.; Huang, C.C.; Chen, J.W.; Lee, W.S.; Chuang, C.L.; Chang, C.C.; Chen, H.M.; Huang, C.C. A core competence-based objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) in evaluation of clinical performance of postgraduate year-1 (PGY1) residents. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2011, 74, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Luimes, J.; Labrecque, M. Implementation of electronic objective structured clinical examination evaluation in a nurse practitioner program. J. Nurs. Educ. 2018, 57, 502–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meskell, P.; Burke, E.; Kropmans, T.J.; Byrne, E.; Setyonugroho, W.; Kennedy, K.M. Back to the future: An online OSCE Management Information System for nursing OSCEs. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snodgrass, S.J.; Ashby, S.E.; Rivett, D.A.; Russell, T. Implementation of an electronic objective structured clinical exam for assessing practical skills in pre-professional physiotherapy and occupational therapy programs: Examiner and course coordinator perspectives. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2014, 30, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricio, M.F.; Julião, M.; Fareleira, F.; Carneiro, A.V. Is the OSCE a feasible tool to assess competencies in undergraduate medical education? Med. Teach. 2013, 35, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkureishi, M.A.; Lee, W.W.; Lyons, M.; Wroblewski, K.; Farnan, J.M.; Arora, V.M. Electronic-clinical evaluation exercise (e-CEX): A new patient-centered EHR use tool. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochlehnert, A.; Schultz, J.H.; Möltner, A.; Tımbıl, S.; Brass, K.; Jünger, J. Electronic acquisition of OSCE performance using tablets. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2015, 32, Doc41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 140, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, S.; Koch, I.; Settmacher, U.; Dahmen, U. How the introduction of OSCEs has affected the time students spend studying: Results of a nationwide study. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhateeb, N.E.; Al-Dabbagh, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Al-Tawil, N.G. Effect of a formative objective structured clinical examination on the clinical performance of undergraduate medical students in a summative examination: A randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatr. 2019, 56, 745–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, S.; Sibbald, D.; Coetzee, K. i-Assess: Evaluating the impact of electronic data capture for OSCE. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2018, 7, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruwais, N.; Wills, G.; Wald, M. Advantages and challenges of using e-assessment. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2018, 8, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerger, S.; Kroehne, U.; Goldhammer, F. The transition to computer-based testing in large-scale assessments: Investigating (partial) measurement invariance between modes. Psychol. Test. Assess. Model. 2016, 58, 597–616. [Google Scholar]

- Nicol, D. E-assessment by design: Using multiple-choice tests to good effect. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2007, 31, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, R.K.; Strand, J.; Gray, T.; Schuwirth, L.; Alun-Jones, T.; Miller, H. Development of a tool to support holistic generic assessment of clinical procedure skills. Med. Educ. 2008, 42, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crews, T.B.; Curtis, D.F. Online course evaluations: Faculty perspective and strategies for improved response rates. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2011, 36, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropmans, T.; O’Donovan, B.G.G.; Cunningham, D.; Murphy, A.W.; Flaherty, G.; Nestel, D.; Dunne, F. An online management information system for Objective Structured Clinical Examinations. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2012, 5, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, E. Implementation and student perceptions of e-assessment in a chemical engineering module. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2013, 38, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gikandi, J.W.; Morrow, D.; Davis, N.E. Online formative assessment in higher education: A review of the literature. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 2333–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question | Mean ± SD # | p Value a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | |||

| Theme one: Satisfaction with the operation of EAS | ||||

| Q1: | Operational convenience | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | <0.001 *** |

| Q2: | Scoring convenience | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | <0.001 *** |

| Q3: | System functionality | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 0.001 ** |

| Q4: | System stability | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | <0.001 *** |

| Q5: | Overall satisfaction with the system | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | <0.001 *** |

| Theme two:Satisfaction with the tablets and network signals | ||||

| Q6: | Network stability | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | <0.001 *** |

| Q7: | Network transmission rate | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.7 | <0.001 *** |

| Q8: | Resolution of the tablet screen | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 0.001 ** |

| Q9: | Data-processing speed of tablets | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 0.001 ** |

| Q10: | Stability of tablets | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 4.8 ± 0.5 | <0.001 *** |

| Q11: More Convenient to Use | Pre # | p Value a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAS | Paper-based | |||

| Post | EAS | 3 | 6 | <0.05 * |

| Paper-based | 0 | 3 | ||

| Q12:Clearer in Formation | Pre | p value | ||

| EAS | Paper-based | |||

| Post | EAS | 5 | 5 | <0.01 ** |

| Paper-based | 0 | 2 | ||

| Q13:Make Examiners More Mobile | Pre | p value | ||

| EAS | Paper-based | |||

| Post | EAS | 5 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Paper-based | 0 | 6 | ||

| Q14:Make Examiners More Nervous | Pre | p value | ||

| EAS | Paper-based | |||

| Post | EAS | 10 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Paper-based | 0 | 2 | ||

| Q15:Speedier Evaluation | Pre | p value | ||

| EAS | Paper-based | |||

| Post | EAS | 7 | 5 | <0.05 * |

| Paper-based | 0 | 0 | ||

| Q16:More Convenient in Processing Data | Pre | p value | ||

| EAS | Paper-based | |||

| Post | EAS | 9 | 3 | <0.05 * |

| Paper-based | 0 | 0 | ||

| Q17:Which is Your Preferred Method | Pre | p value | ||

| EAS | Paper-based | |||

| Post | EAS | 7 | 6 | <0.05 * |

| Paper-based | 0 | 0 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chuo, W.-H.; Lee, C.-Y.; Wang, T.-S.; Huang, P.-S.; Lin, H.-H.; Wen, M.-C.; Kuo, D.-H.; Agoramoorthy, G. Evaluate the Feasibility of the Implementation of E-Assessment in Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) in Pharmacy Education from the Examiner’s Perspectives. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050194

Chuo W-H, Lee C-Y, Wang T-S, Huang P-S, Lin H-H, Wen M-C, Kuo D-H, Agoramoorthy G. Evaluate the Feasibility of the Implementation of E-Assessment in Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) in Pharmacy Education from the Examiner’s Perspectives. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(5):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050194

Chicago/Turabian StyleChuo, Wen-Ho, Chun-Yann Lee, Tzong-Song Wang, Po-Sen Huang, Hsin-Hsin Lin, Meng-Chuan Wen, Daih-Huang Kuo, and Govindasamy Agoramoorthy. 2021. "Evaluate the Feasibility of the Implementation of E-Assessment in Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) in Pharmacy Education from the Examiner’s Perspectives" Education Sciences 11, no. 5: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050194

APA StyleChuo, W.-H., Lee, C.-Y., Wang, T.-S., Huang, P.-S., Lin, H.-H., Wen, M.-C., Kuo, D.-H., & Agoramoorthy, G. (2021). Evaluate the Feasibility of the Implementation of E-Assessment in Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) in Pharmacy Education from the Examiner’s Perspectives. Education Sciences, 11(5), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050194