1. Introduction

The intensification of the research on bi- or multilingual education has been reflected in the dynamics in international migration patterns. Over the last four and a half decades, the number of international migrants has almost tripled around the world [

1], and the research published in the field of bi- or multilingual education has increased at a similar rate according to the Web of Science records [

2].

The research evidence is rather unanimous on issues, such as the superiority of well-implemented bilingual programs over monolingual ones; the key importance of using the student’s first language (L1) for an extensive period of time in bilingual programs; and the precedence of two- or one-way immersion programs over other types of approaches (for a most recent overview see [

3]). However, despite a lengthy tradition of inquiry, the research remains vague on the question of what specific factors need to be in place to make multilingual education effective.

Consequently, Uchikoshi and Maniates [

4] called for more empirical work on the quality of program implementation “to understand the explanatory variables for academic success in bilingual programs”. Likewise, Valentino and Reardon [

5] underscored that research on various bilingual instructional models has left unanswered the question of which components make the programs work.

In this article, we aim to contribute to this research gap by reviewing the research evidence on specific factors explaining multilingual student success in bi-/multilingual (only the term ‘multilingual’ will be used hereafter; in the review of articles found through the search, the term originally used in the article will be used) education programs. Through a systematic literature review, a summary of factors will be presented.

2. Multilingual Education and Effective Schools

Traditionally, in education research, school effectiveness scholars have been the ones occupied with the question of specific factors explaining success. Effective school research (ESR), a strand of the wider school effectiveness research paradigm, has aimed to identify the processes of effective schooling [

6]. ESR has attempted to explain how successful schools function differently from less successful ones. Reynolds and Teddlie [

7] summarized that effective schools were characterized by nine process factors: effective leadership, effective teaching, a pervasive focus on learning, a positive school culture, high expectations for all, student responsibilities and rights, progress monitoring, developing school staff skills, and involving parents.

However, ESR has been only marginally addressed in multilingual education contexts. A research review of the major context factors studied in school effectiveness concluded that, most often, socioeconomic status is under review followed by less researched contextual factors, such as community type, grade phase, and governance structures [

8]. Consequently, the language aspect has not been identified as a major category of contextual variables in the ESR paradigm. At the same time, scholars of multilingual education have claimed that these factors should take precedence before more specific effectiveness variables can be discussed [

9,

10].

The studies on multilingual school effectiveness have evolved separately from ESR. Carter and Chatfield [

11] were some of the early authors to make an interconnection with bilingual education programs and school effectiveness by proposing a Bilingual/Effectiveness Paradigm. They raised a question regarding the interdependence of bilingual education programs and the schools they were situated in. They concluded that “the school does not make the bilingual program effective; neither does the program make the school effective. The program, as an integral part of school activities, contributes to and mirrors the overall effectiveness.” [

11] Still, it seems that these aspects have not been given enough consideration as researchers on multilingual education still make claims regarding a lack of evidence in this area [

4,

5].

The analysis of contextual factors has mostly received attention in ethnographic studies that provide more thorough descriptions of multilingual education in particular settings; however, these have been rather few in number (see May [

3] for an overview).

There have been a few studies that focused on summarizing the evidence on multilingual education variables. However, most of these are not very recent. In 1992, Christina Bratt Paulston carried out a paradigmatic analysis of bilingual education and concluded that the independent (causal), dependent (outcome), and intervening variables of bilingual education programs depended on the world view of the researcher [

12]. The US National Research Council identified, in their 1997 study, 13 factors characterizing effective schools for English-language learners [

13].

Maria Estela Brisk published an extensive book in 2006 addressing all possible factors affecting the functioning of quality bilingual education [

14]. In her book, Brisk concluded her study of influential variables with a Framework for School Evaluation where she listed 26 factors at school, curricula, and instruction levels for schools to evaluate and follow as critical for quality bilingual schooling. Additionally, Baker [

15] discussed key topics in effective bilingual schools.

As Bratt Paulston’s [

12] work was not aimed at summarizing the available evidence and those by Baker [

15], Brisk [

14], and the US National Research Council [

13] were not systematic reviews and are somewhat outdated by now, a refreshed look at the most recent works on the effectiveness of multilingual education appeared necessary. Additionally, during the times of information overload and the diversification of the student populations [

16], education policy makers are in critical need of up-to-date and trustworthy concise information on the evidence of what works in multilingual education and what factors contribute to effectiveness.

In other words, education decision makers require updated information on what variables are associated with more effective outcomes in multilingual education so that when designing or revising their own programs they can already utilize the knowledge available. Additionally, this type of research would suggest to what extent the factors are under the control of school leaders.

Consequently, based on the need to (a) map the contemporary state of the field of effectiveness in multilingual education and (b) to compile evidence for actors in multilingual education, a literature review with the aim of providing an overview of factors shaping the effectiveness of multilingual education was conducted. The research question to be addressed was: which factors are associated with the effectiveness of multilingual education?

3. The Conceptual Framework of the Factors Shaping Multilingual Education

Several authors researching multilingual education [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] have conceptualized and proposed factors affecting the functioning of multilingual education. These conceptualizations vary extensively in terms of their content, level of analysis, and the variables covered (see also [

22]). There is no apparent consensus among the researchers in the field regarding how the factors shaping the operation of multilingual education should be viewed and conceptualized.

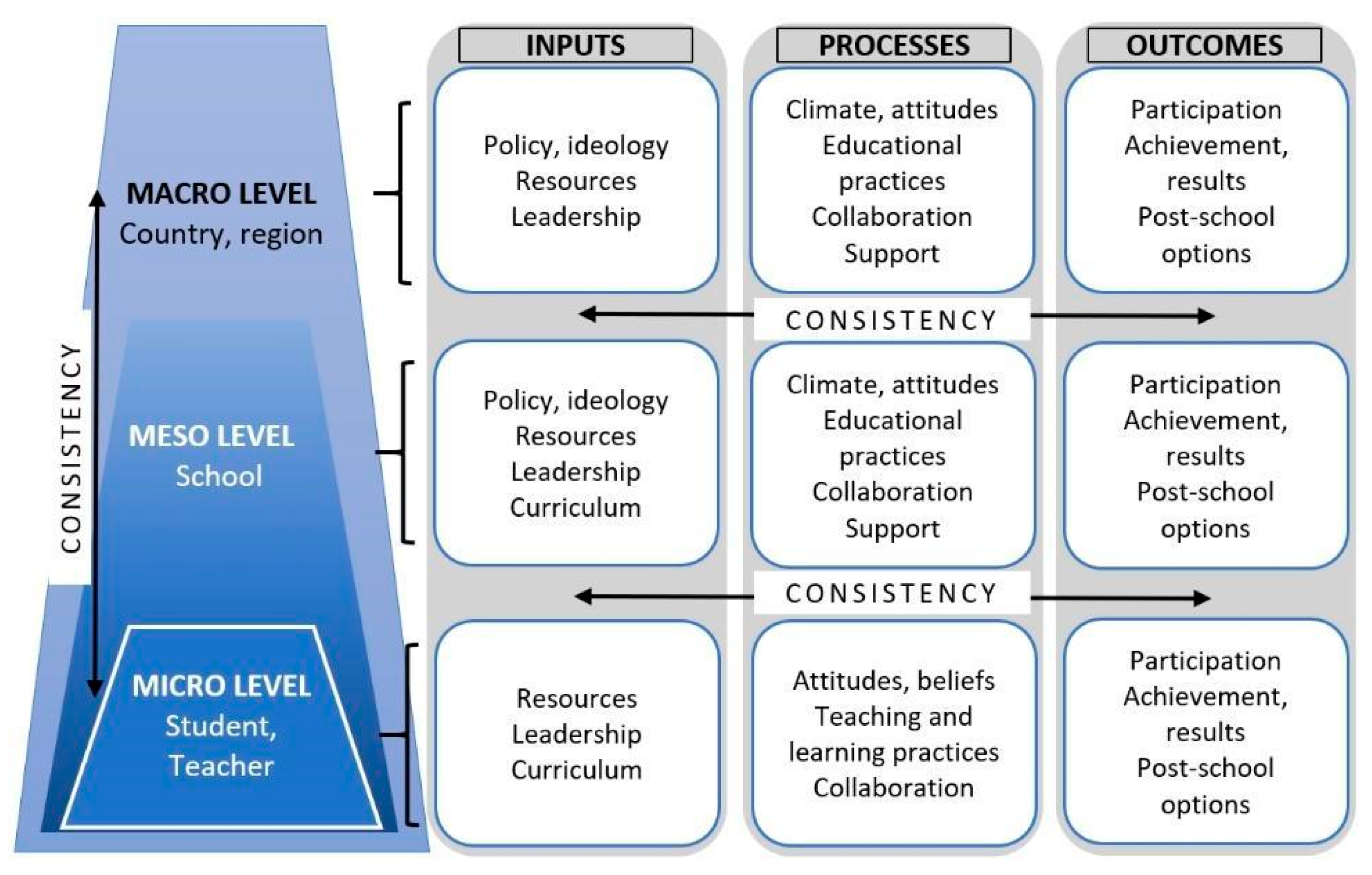

Based on this need, we proposed a conceptual framework (for an overview, see [

22]) that would comprehensively cover the different levels of analysis and functioning (macro, meso, and micro) of multilingual education, differentiating between variables based on their types (inputs, processes, and outcomes). Adopting a system view of the framework, this framework allows a systematic analysis of the factors at play in multilingual education as well as reviewing to what extent different levels and types of factors function in a consistent manner.

Figure 1 below provides a visual overview of the factors and the main sub-factors. The literature review provided in the later sections of the paper uses this conceptual framework as a basis for the analysis: all of the factors located in the literature review process are recorded under these categories and sub-categories. Using this framework enables an overview of what types of factors, at what levels, occur in studies dealing with the effectiveness of multilingual education.

4. Method

A systematic literature review search was carried out in September 2018 as part of the RITA-Ränne research and development project in Estonia. The following search terms were used: ‘bilingual education’ OR ‘multilingual education’ AND effective*. The choice of search terms was based on the idea that the most common and used terms were included, while the more specific alternatives that refer to particular types of bilingual education (e.g., two-/one-way immersion, dual-language education, content and language integrated learning, sheltered instruction, etc.) were excluded.

The inclusion of all possible versions and types of multilingual education would have made the search immensely extensive. The search term ‘effective’ was purposefully included to limit the search to studies that try to address factors explaining the success of multilingual education; this was also directly in line with the research question. Detailed PICO was not implemented as bi/multilingual education is not a clear-cut intervention; thus, PICO was not deemed appropriate to apply.

The academic databases the Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, EBSCO ACADEMIC SEARCH COMPLETE, and ERIC were used for the search. The search criteria included peer-reviewed journal articles; additionally, books and book series were included in Scopus (as this was an available option); conference proceedings were excluded as these were not considered to be of the same academic quality as journals and books. Only English language sources were included.

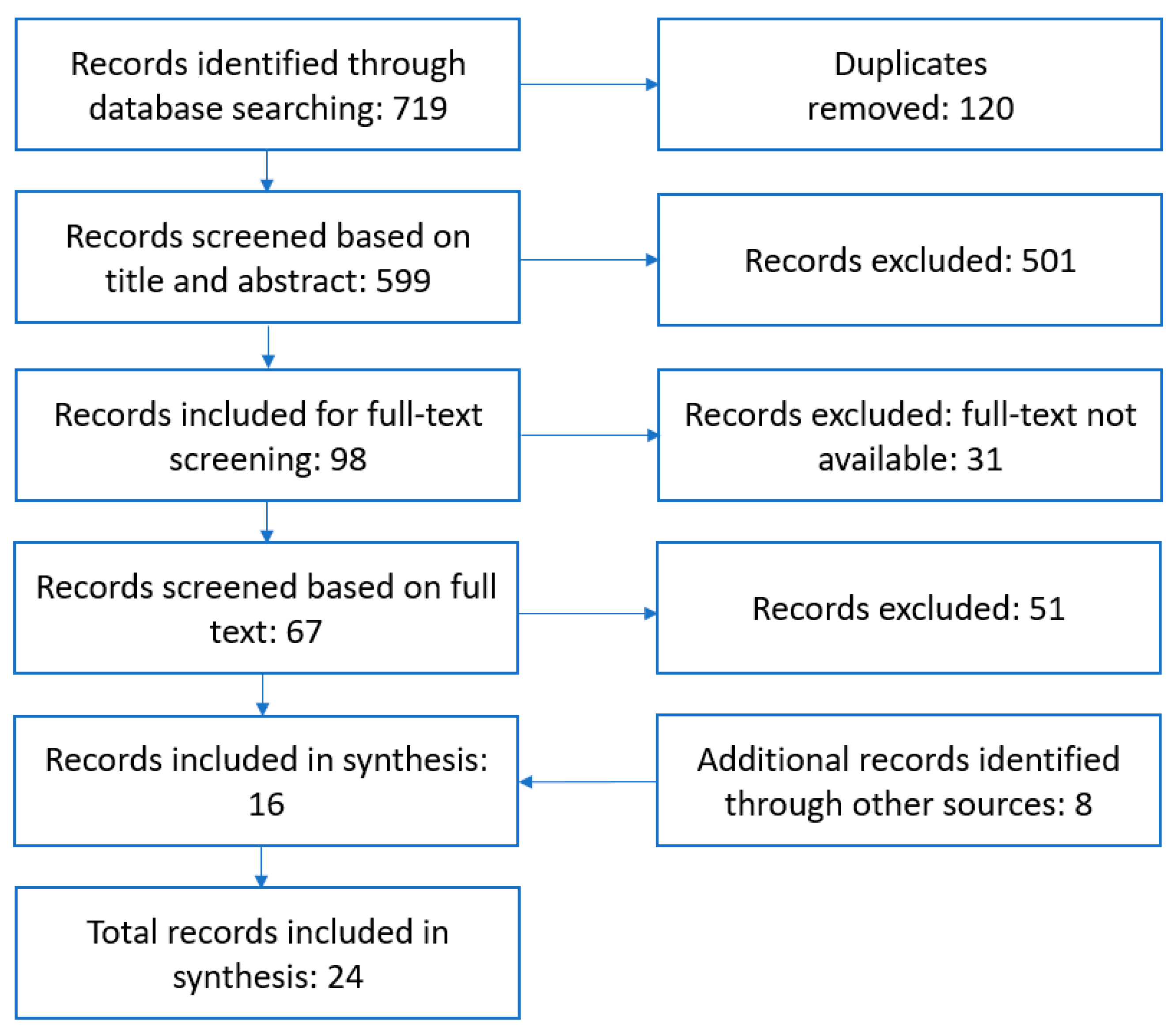

The databases’ search yielded a total of 719 publications; with the removal of duplicates, 599 publications remained (see

Figure 2 below). Then, a first screening based on title and abstract was carried out using the following inclusion (eligibility) criteria:

Bi/multilingual education: the study addressed multilingual (or any sub-type of this) education.

General school education: the study involved students in K12 education.

Regular education: the students were involved in regular and not in special needs education.

Type of study: the study was an empirical investigation of multilingual education and not a theoretical piece of writing; also, book reviews were excluded.

Effectiveness of multilingual research: the study explicitly dealt with effectiveness or some aspect of the effectiveness of multilingual education.

Explanatory nature: the study addressed factors affecting the effectiveness of multilingual education and did not only compare different types of programs and their effectiveness.

Language of study: only papers in English were included.

The screening was carried out with the EPPI-Reviewer 4 program [

23]. At the title and abstract stage of screening, two coders were used for reviewing the search results. Out of the 599 articles, 323 (54%) were co-coded by both coders to increase the trustworthiness of results. Of the 323 articles co-coded, 236 (73%) were coded similarly. In case of disagreements (87 articles, 27%), a reconciliation was done in cooperation with the two coders: the articles under disagreement were again revised and then the final decision was made on inclusion/exclusion.

The title and abstract screening resulted in 98 included articles; out of these, 31 were not accessible in full text to the authors and had to be excluded from further analysis. Then, the full text screening of 67 articles was carried out.

The full text screening ended up with 16 included articles; additionally, eight more studies that were previously known to the authors and that did not show up in the search were included in the review process. These additionally included studies were mostly of three types: well-known and recognized longitudinal studies in the field that had not been published in journals [

24,

25]; research reports carried out or commissioned by national government agencies [

26,

27]; and studies located during a previous literature search done on the theoretical framework for multilingual education [

28,

29,

30,

31].

In total, 24 articles were included in the final analysis of the literature review. The tables in

Appendix A (

Table A1,

Table A2 and

Table A3) provide an overview of the included studies.

The data analysis process of the 24 included articles was largely based on the PRISMA checklist [

32], and a detailed review of the writings in terms of the research objective, the research questions/hypothesis posed, the research object, the theoretical framework used, and the variables (input, process, and output) addressed was performed for each study.

Additionally, the location, target group, sample size, methodology, type of evidence, aspects of reliability/trustworthiness, and main conclusions were recorded for each study. The studies were also categorized into study types: quantitative (11), qualitative (7), and mixed (6) method studies (cf.

Appendix A Table A1,

Table A2 and

Table A3). After that, the data were analyzed based on the categories outlined in

Figure 1, e.g., all macro level resource factors found were put together and analyzed in terms of what aspects of resources were discussed in the articles found.

After this review process, the results were systematized based on the developed analytical framework of the factors shaping multilingual education (see

Figure 1).

5. Results

Before starting to uncover the particular findings of the study, we briefly discuss the more general nature and content of the studies reviewed to provide a backdrop to the factors discussed later. The majority of studies found were conducted in the USA, with two meta-analytic studies covering the whole world.

The origins of the studies have clear implications on how the research objects were framed in the reviewed writings. The majority of studies (11 out of 24) had a set focus on analyzing English (language) learners, followed by an equivalent of limited English language proficient (6) students—both terms mostly used in the US context. However, the rest of the studies used a wide array of research object terms (e.g., English as second language (learners) or L2 learners, dual language learners, language minority students, immigrant students, emergent bilinguals, and bilingual learners).

The framing of the research objects often allows an assumption of what kind of theoretical stance has been taken by the authors. In this case, the most frequently used theoretical framework was bilingual education theory; however, closely related theories of English language/second language learning, dual language learning, and foreign language learning were also adopted. School effectiveness and content and language integrated learning (CLIL) frameworks were also present. However, the variety of theories emerging was rather large—depending on the research questions applied, certain theories were more specific in focusing on pedagogical practices or language learning strategies. Theoretical frameworks from sociocultural approaches, bioecological research, and psycholinguistics were also represented.

The following sections discuss the research results based on the conceptual framework outlined in

Figure 1. The results reflect the state of the available research as of September 2018.

5.1. Outcome Variables Used in Effective Multilingual Schools’ Research

Before moving to the discussion of effectiveness variables, an overview of the output or outcome measures applied in the reviewed articles is provided. The output variables indicate how various authors have approached the concept of effectiveness and what has been defined as success in multilingual education. This not only provides an overview of the types of measures used to define effectiveness or success but also outlines a wider contextual background for the input and process factors discussed in the following sections.

Table 1 below summarizes the output/outcome indicators used and proposed in the reviewed articles. On the one hand, the variety of indicators is rather extensive in outlining the multitude of possibilities to approach the outputs of multilingual education. On the other hand, the review clearly indicates that the focus of outputs was predominantly on language skills and/or academic achievement in major curriculum subjects.

However, the review of output indicators was revealing in the sense that other outputs in addition to academic ones were rarely under review for researchers. Multilingual education often promotes other types of objectives (e.g., the appreciation of diversity, intercultural competence, etc.); however, as seen from these reviews, these outputs were not often included in the multilingual education effectiveness concepts.

5.2. Input Factors Contributing to Effective Multilingual Schools

5.2.1. Policy and Ideology

Policy is understood here as the articulated intentions of policy makers as well as the guidelines for practice [

33]. Educational ideology reflects a “world-view or set of assumptions regarding education” [

34] signifying the main focus of the policy. In the reviewed papers (see

Table 2 below), the majority of findings discussed school-level policy and ideology issues while only two—by Berman et al. [

26] and Mehisto and Asser [

35]—made reference to macro level issues. At the state level, Mehisto and Asser’s [

35] study indicated that schools regarded it important to have national guidelines and support systems in place for implementing multilingual education.

Berman et al. [

26] found that all reviewed states had regulations in place that ordered schools to have special programs for students with limited English proficiency. This meant that schools with a certain number of limited English speakers had to implement targeted programs for these students. In some cases, regulations also presented specific requirements for teacher credentials (training). The practices at the district level were more varied, but overall, districts of exemplary schools stood out with their support for students’ development of bilingualism and biliteracy underscoring the ideology of additive language learning.

Berman et al. [

26] also found evidence of a belief in limited English proficient students’ high achievement by district management personnel. Another indicator of the policy steps taken were the extended autonomy and accountability of decision making to individual schools, thus trusting the schools with finding the best solutions for their student body. In certain cases, adjustments in regulations (e.g., class size limits) were offered to support schools.

At the school level, exemplary multilingual schools were characterized by a clear multilingual language policy focus of the school. García et al. [

36] identified a ‘bilingualism in education’ policy at the researched schools that sought to flexibly address the various needs of bilingual learners. The schools that Alanis and Rodriguez [

37] and de Jong [

38] researched had explicitly stated the goals of multilingualism and multiculturalism in their policy documents. Not only was multilingualism stated as a goal at effective schools but school policies also reflected that multilingualism is a valuable resource per se, i.e., an enrichment ideology was being followed [

37]. At the same time, Alanis and Rodriguez [

37] also noticed how language development was not prioritized over academic or social development—a balanced development in all three areas was sought.

The school language policy and goals were derived based on the analysis of specific community needs [

36,

39,

40], and the program models offered were developed based on research evidence (i.e., theory and best practices) [

37,

38,

40,

41]. The programs implemented at successful schools made room for flexibility in implementation based on the analysis of students’ special language needs [

37,

38,

41]. Thus, the programs and supports were tailored according to the student language proficiency levels and development. The constant monitoring of the success of multilingual students was underscored in policy and enabled adjustments in curriculum and practice [

37,

38,

41].

5.2.2. Resources

Well-performing multilingual schools require various types of critical resources to make learning effective. Loreman et al. [

33] viewed resources as including financial as well as other types that are critical for education provision. As the

Table 3 below suggests, facilitative resource factors were identified consistently at all three levels: the macro, meso, and micro levels. To begin with, successful multilingual education provision was conditioned by the local setting (the prevalence of L2 learners in the region) so that a second language could be used informally in addition to formal school-based use as Dixon et al. [

30] found.

The particular resources made available by the state or regional educational administrators for schools were found to matter greatly. It was critical for funding to account for the nature of education provided and to set aside financing for implementing multilingual education at schools [

26,

35,

36,

39]. The educational staff was recommended to be kept abreast of the needs of schools, including regular professional development offered to teachers and administrators [

26,

42]. Berman et al. [

26] identified the establishment of professional development networks for teachers. The availability of instructional material for multilingual education provision was also underlined in the literature ([

35,

38].

At the school level, in addition to the expected factors of availability of funding [

35,

36,

39] and teaching and learning materials for implementing multilingual education [

35,

38], the availability of staff with critical competence was also stressed. First, successful implementation of multilingual education begins with a leadership knowledgeable in multilingual education specificities.

Buttaro [

42] showed how school leaders have been identified to have qualifications in bilingual education or in English as a Second Language. The schools reviewed in their study had leaders who also acted as instructional leaders monitoring classrooms and performing oversight of the teaching and learning (see more on leadership below). Secondly, schools needed to have access to teachers capable of implementing multilingual education. At successful schools, pedagogues were characterized by bi/multilingual abilities, the knowledge of linguistics and teaching and learning languages, specific preparation in bilingual education, and high levels of cultural awareness [

4,

26,

30,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42].

At the level of students, the review demonstrated that educational success was facilitated by strong home literary practices, e.g., in the form of book reading or asking questions [

30] and also by resources, such as good native language abilities [

28]; a supportive attitude, aptitude, and motivation to learn languages [

28,

30]; a high socioeconomic background [

29,

31]; and the use of the second language in student social networks [

29].

5.2.3. Leadership

Loreman et al. [

33] drew attention to two major aspects in the case of leadership that was supportive of inclusive education: values and creating conditions for teachers to be able to implement inclusive education. The literature review identified several factors that related to leadership values and how schools are run based on these values (see

Table 4 below). First, several authors [

35,

36,

37,

40,

42] underscored the true commitment of the leaderships to making multilingual education work in their schools. The principals must themselves be true believers in multilingual education in order to inspire and lead the rest of the organization in this mission.

The teachers appreciate the support provided by principals, recognizing their key role in making the programs a success [

26,

35,

40]. Alanis and Rodriguez [

37] showed how teachers gained belief in the value of multilingual programs—this was a conscious and planned action by the leadership to help teachers understand the goals and philosophy of the program. The heads of schools were intentionally working in the name of building “leadership capacity among her teachers by allowing them to implement creative strategies in the classroom and encouraging them to take on leadership roles” [

37].

Secondly, the commitment of leaderships was often preconditioned by their competence on the subject matter. The principals had often either obtained academic degrees in bilingual education [

42] or had made a habit of keeping themselves abreast of most current research in the field [

37].

Thirdly, commitment and knowledge led to evidence-based management of the programs [

35,

37,

40,

41]. This means that using data and research was an integral part of running the programs, and the best practices were taken advantage of in favor of the program. Following the research and best practices in the field also suggests that those leaders were open to change and innovation—key factors underlined by Robledo Montecel and Danini [

40].

Fourthly, the research review also identified how success could not be achieved without a cooperative culture in the organizations [

36,

37,

39,

40]. Leaderships in outstanding multilingual schools had internalized inclusive decision-making cultures so that the school members were involved in important decision-making, and therefore a basis for wide-scale ownership of change was created.

Finally, Robledo Montecel and Danini [

40] added that strong leaders in successful multilingual schools tended to stand out in their capacity to guarantee the necessary resources for running the schools well.

5.2.4. Curriculum

When discussing curriculum issues with inclusive education indicators, Loreman et al. [

33] emphasized the universal design for learning where the diversity of learners needs to be accounted for—this applies to teaching representations, means of engagement, and opportunities for expression. The research into the curricula of outstanding multilingual schools showed that similar curricula had been applied in these schools (see

Table 5 for details). First, the reviewed articles demonstrated how the curricula were focused on including student home cultures and languages [

4,

24,

25,

26,

37,

40,

43,

44] so that the teaching and learning would be linguistically and culturally relevant.

For instance, Berman et al. [

26] showed how a curriculum was set up so that, in language arts classes, the literature selection could be based on the students’ cultural experience; or how, in Science and Math, the students’ environments and real-life situations were driving the focus of learning. García et al. [

36] demonstrated how the curriculum enabled implementing translanguaging practices in teaching and learning as well as including personal experiences in the selection of class readings. Secondly, the reviewed articles demonstrated high levels of flexibility in order to account for the particular needs of multilingual students [

26,

36,

39,

40,

41].

Smith et al. [

41] underlined the importance of providing different types of programs according to varying student needs and also emphasized the flexibility of the structure and format of classes to meet different language proficiency levels. Thirdly, the research showed clearly that successful multilingual programs needed to include the students’ first language in the curricula—not only do students need to be taught their first language as a subject, but they also need to study subjects in their first language.

Guglielmi [

44] demonstrated how Hispanic Limited English Proficient (LEP) students’ high-level proficiency in their native language (L1) predicted English reading (L2), which, in turn, was related to later academic and occupational success. In another study, Guglielmi [

43] found a similar connection for subject learning: Hispanic students’ L1 results predicted their Math and Science achievements. Thomas and Collier [

24,

25] demonstrated that minority students achieved the highest English proficiency and academic results in cases where the curriculum was set up so that L1 was taught as a subject as well as used as a medium for learning alongside L2.

5.3. Process Factors Contributing to Effective Multilingual Schools

5.3.1. Climate, Attitudes, and Beliefs

Loreman et al. suggested that the social climate consists of the beliefs and attitudes of all members of the educational community [

33]. Then, how can the social climate be described in successful multilingual schools?

Table 6 below summarizes the findings. First, it is important to investigate how school members view cultural diversity at school—whether this is appreciated or not. Many authors [

26,

36,

40] demonstrated how cultural and linguistic diversity was a norm at school and was valued and seen as a resource rather than a problem. The same can be applied to multilingual education: in outstanding multilingual schools, education in multiple languages was respected and highly appreciated [

26,

36,

37,

39,

40,

41]. This value was also reflected in the linguistic landscapes of schools and respective classrooms [

36,

37].

Secondly, successful multilingual schools exhibited a culture of caring [

26,

36,

40,

42]. García et al. [

36] described how “Teachers, counsellors, and administrators modelled care as they went above and beyond the parameters of a job description. Putting in extra time, resources, and assistance to improve student experiences and achievement was a common occurrence among adults of various roles, and many saw themselves as advocates for students”. García et al. [

36] identified that the care they saw permeated various aspects of schooling and thus called this phenomenon “transcaring”.

Thirdly, several authors underscored that the school cultures reflected the belief in cooperation and collaboration [

24,

25,

26,

36,

40,

42]. This was seen to be taking place in how teaching and learning was set up and practiced. It was natural how members of the schools were used to working together. The cooperative spirit also extended beyond school; thus, the inclusion of parents was seen as a valuable resource.

Fourthly, one critical aspect in school culture was in setting high expectations for all students regardless of their background or language skill. As was shown [

26,

37,

40,

42,

45], it is vital to treat students with limited English equally with other students and expect high performance from them—a practice unfortunately not common across all schools with minority students. The attitudes and beliefs described for schools were also shown to be characteristic of teachers.

5.3.2. Practices

According to Hordern [

47], ”the ‘theory’ and ‘practice’ are inseparable, interwoven, and mutually constituted”, with practice primarily related to what educators do in their workplace settings, and educational practice considered to be the normative traditions or certain habituated activities that are sustained over time with consensually agreed purposes, criteria of excellence, and practitioner mutual accountability.

Loreman et al. [

33] determined seven elements that together represent effective teaching practices, which were initially found useful for the inclusion of students with special needs; however, the authors claim they are the universal foundations of good instruction that allows providing instruction according to various learner needs and learning characteristics.

Educational practices promoting bi-/multilingualism include factors related to languages, languages in use in school environment, the language skills of both students and teachers, and methods and teaching approaches in use both as a school’s common practice and teachers’ teaching habits (see

Table 7 below). For example, one of the promoting factors is the use of students’ primary language (L1) in schools [

26,

36,

37,

38,

45], and, in correlation with that, effective L2 teachers are said to demonstrate sufficient L2 proficiency, strong instructional skills, and proficiency in their students’ L1 when engaging in school life [

4,

30]. In addition, there ought to be focus on contact between students of L1 and L2 [

26], and the academic development in both languages should be considered in school activities [

4].

One distinguishing feature that connects several promoting factors is flexibility and complaisance toward linguistic differences: diverse and flexible curricular models are coupled with adjusted evaluation and assessment criteria [

36,

40]; the teaching–learning of languages is different from traditional methods, including the personalization of learning [

5,

25,

36,

37,

38].

According to Thomas and Collier [

25], the focus of the program should be on academic enrichment for all students, with intellectually challenging, interdisciplinary, and discovery learning. They also indicated that the program would then become positively perceived by the community. The activation of students can also be detected in other indicators, such as involving the students in planning their own learning [

26], experiential and inquiry-based learning methods [

26,

45], or dialogical/cooperative and interaction-based learning approaches [

26,

36,

37,

40,

42,

48]. Ardasheva [

28] proposed that the learner’s ability to use different learning skills should be taught at school.

The elements of tolerance toward diversity as well as authenticity were also recurring among promoting factors, such as a culturally responsive approach to learning [

4,

26,

36], the use of authentic materials [

36,

38], and the attention paid to prejudice reduction [

36].

5.3.3. Collaboration

Loreman et al. [

33] characterized collaboration as participatory partnerships at different levels both inside and outside schools. Evidence of collaboration processes was found at the region, school, and individual levels (see

Table 8 below).

At the school level, the literature review suggested that successful multilingual schools internalized the involvement of parents into school life and cooperated with them as partners on a regular basis. Alanis and Rodriguez [

37] characterized how parents were kept informed of the program and were involved in the program planning to secure continued support for the chosen model. Parental volunteering in classes was also facilitated [

37]. Successful bilingual schools took parental involvement seriously; some even set in place special roles, e.g., Parent Involvement Facilitators [

41] or Parent Coordinators [

36].

In addition to parents, the inclusion of the local community and other external partners was a norm at well-faring multilingual schools. García et al. [

36] characterized how Latino youth were provided access, thanks to external partners, to various academic support and social development services (e.g., mental health, youth development, and college preparation) in order to help them out of the stigmatized English Language Learner role. Berman et al. [

26] showed how external partners, such as various NGOs or higher education institutes, played a critical role in school reform by offering cooperation in the form of coaching, decision making, curriculum revision, and teaching strategies and assessment. Alanis and Rodriguez [

37] also underscored the important role of local universities in staff development and support.

Additionally, it mattered whether collaboration took place at school and what forms this took. Writings outlined that outstanding multilingual schools tended to have inclusive decision-making structures in place. Alanis and Rodriguez [

37] noted how democratic decision-making processes “allowed teachers and parents to have ownership of the program”. Similarly, García et al. [

36] also observed democratic leadership styles in school management and underscored the key role of the principal in leading by vision while creating favorable conditions for teacher empowerment.

García et al. [

36] identified how teacher collaboration was prioritized and supported at schools: teamwork had become an integral part of the school day and helped teachers to review student progress. As Robledo Montecel and Danini [

40] presented: “there was evidence of horizontal linkages as well, with teachers working in teams, sharing, exchanging, communicating, and focusing on achievement of all students”.

Buttaro [

42] also identified the practice of teachers meeting and discussing vertical or grade level planning issues. Berman et al. [

26] experienced how team teaching was successfully and flexibly carried out at the researched schools. Altogether, successful multilingual schools established communities of learners inside the schools to promote student success.

5.3.4. Support

Loreman et al. [

33] viewed the category of support primarily through the individual learner’s lens and referred to different types of assistance provided through in-classroom resources or outside the regular classroom by various educational professionals. Since this aspect only tends to cover the school- (meso) and individual- (micro student) level factors, we also extended this to include a macro view to enable a more comprehensive picture of the support factors listed in the literature (see

Table 9 below for details). At the macro level, the identified studies discussed the importance of local government/district support in more general terms as a factor contributing to success [

35] and also in terms of providing support for leadership, respect for the program, and effective communication [

40].

Additionally, the studies [

26,

39,

42] had specific examples of state and district support in the format of support for teacher and administration professional training, recruitment help, providing a framework for reform (new concepts of education, school network establishment) for schools, sponsoring and offering professional development networks and stipends for teachers, providing a parental involvement program, setting aside restructuring grants for school innovations and specific development needs, and supporting schools’ goals of developing students’ bilingualism.

At the school level, García et al. [

36] provided a detailed description of various support activities that were provided to Latino students. Within schools, students were offered academic and linguistic tutoring before and after classes as well as on weekends and summers if necessary. García et al. also found evidence of well-established extracurricular programs, targeted programs for mental health support as well as various partnerships with different community organizations—all set in place to support the development of Latino youth academically and socially.

Assistance services were also offered to parents with the intention of increasing their involvement. English as a Second Language classes were additionally offered to parents so that they could more effectively participate in information dissemination; help their children; and gain first-hand experience of second language learning to foster greater understanding [

36,

37]. Berman et al. [

26] identified the importance of integrated health and social services with educational services at schools; extensive parent education programs and after-school tutoring were found at successful schools.

6. Discussion

This article set out to investigate which factors were associated with the effectiveness of multilingual education. Brisk [

14] claimed that “the pieces of the educational puzzle exist, but they are scattered”. We made an effort here to collect and organize those pieces of evidence on what characterizes successful multilingual education. In the systematic literature review, we set the results into our previously developed conceptual framework [

22] (see

Figure 1).

The integrated theoretical framework of the effectiveness factors enabled analysis of multilingual education in a systematic and comprehensive way by checking to what extent the critical factors were in place at individual schools (see also the web tool at

http://kodu.ut.ee/~kirsslau (accessed on 20 April 2021). Brisk [

14] underscored the interdependence of success factors and emphasized that schools often attempt to pay attention to several critical factors at once, although she also conceded that a step-by-step approach where schools follow a plan of improvement is also feasible. Loreman et al. [

33] suggested that school systems plan their activities backwards starting from the outcomes by adjusting the school practices with the end outcomes firmly in mind (the consistency of the outcomes-processes-inputs).

At large, our review results revealed that most of the chosen studies addressed effectiveness factors related to the school (meso) level, while only a minority discussed more general (macro) or more detailed (micro) aspects as well. This could be potentially explained by the methodological choices made in the research process (see more in the Limitations section). At the same time, this reflects the nature of the studies being carried out and the focus of the authors reviewed.

That school-level studies describing effective multilingual schools almost never reflected on the wider context of studies or the factors having relevance on the functioning of schools was surprising. The socioeconomic context of studies is traditionally discussed; however, the wider economic, legal, social, linguistic, etc., aspects were very rarely addressed. The wider context is critical as this often shapes the functioning of schools indirectly and has relevant implications on what can be done at the school level. As Brisk [

14] claimed, these contextual factors have critical importance in how schools judge their students and families.

Resources was one area where all the levels (macro-meso-micro) were addressed in the reviewed studies: national funding principles accounted for the multilingual nature of education, school funding was available for implementing multilingual education, and resources were secured for teachers, including means for additional training. The key variable appeared to be the focus on meeting individual students’ needs. The resources section highlights how the language resources in the wider regional context as well as at the student level could come together in a beneficial way to facilitate learning at school.

The results of the review illuminate to a large extent what the research has underscored as the main processes of effective schools. Reynolds and Teddlie [

7] summarized that effective schools were characterized by nine process factors: effective leadership, effective teaching, a pervasive focus on learning, a positive school culture, high expectations for all, student responsibilities and rights, progress monitoring, developing school staff skills, and involving parents.

The studies reviewed here confirmed these findings to a large extent. We elaborated on the meaning of these factors in a multilingual context by providing a more precise description of effectiveness. The reviewed studies clearly underscored how multilingual schools required both an understanding of the nature of multilingual learning and of how the vision for the school is critical in guiding the various processes of teaching, learning, management, inclusion, etc. The findings concur with what Carter and Chatfield [

11] proposed already more than three decades ago: overall, school management and multilingual education effectiveness are interconnected and interdependent on each other.

The leadership played a critical and central role in effectiveness: expert leadership-based program development on research evidence, negotiated the programs with the community, and prioritized the competence of teaching staff to be able to implement the vision and programs. The focus of learning was not only tilted toward language learning but also toward academic and social development, although, as Brisk [

14] conceded, sociocultural integration was rarely measured as an outcome. In the case of school culture, the true recognition of the diversity of cultures and languages was seen as a resource and value among the school members.

Strong multilingual schools carried the enrichment ideology in their schools so that the presence of students of various cultural backgrounds was not seen as a problem but as an opportunity. In teaching and learning, the first language of students was promoted and the culture included. In the case of progress monitoring, the development of students was carefully monitored and the programs were adjusted according to the needs. As seen from the review, flexibility in program choice and implementation is a key to success. Importantly, good multilingual schools strive to complement educational services with social ones to overcome the socioeconomic disadvantage of minority students and help them succeed in education. The latter is a critical aspect as it reflects schools’ intentional activity to overcome wider social injustices [

12].

Our review also largely confirmed the list of quality bilingual school factors proposed by previous research (see for example Baker [

15], Brisk [

14], or the National Research Council [

13]) and is unique in adding some additional perspectives. Although Brisk discussed various contextual and individual factors in her book, the framework for evaluation addressed only the variables at the school level. Other researchers [

13,

15] have given little attention to the contextual aspects when discussing effectiveness. Our review took a step further and integrated the view of the macro as well as the micro levels and discussed the relevant research results.

In view of the macro level, our study highlights the critical aspects of national/state policy and support, including securing critical resources for schools. At the micro level, we underline some student-level aspects for schools to recognize and account for: the quality of home literary practices; native language abilities; aptitude, attitude, and motivation for learning languages; social background; and the use of L2 in student social networks. Finally, we systematized our results into an interactive web-based application that can be kept up to date with recent research results and is freely available for potential users.

7. Conclusions

This review brought together and synthesized the latest evidence on effective multilingual education while placing the results into a conceptual framework (see

Figure 1). The results have important implications in terms of two aspects. First, by outlining the conceptual framework as the basis of the effectiveness factors, we highlight the wide array of factors that the actors and decision makers in education need to account for when addressing multilingual education issues. The framework underscores the interrelatedness of the factors at the individual, school, and country/region levels as well as the different types of factors.

Secondly, by placing the results into the conceptual framework, we offer evidence on what is currently known regarding what works in multilingual education. The consistency through all different levels of education may be the key aspect to effectiveness. Starting from the intended or expected outcomes of multilingual education, the factors shaping education need to be reviewed and, if necessary, revised at the different levels while keeping in mind the wider societal context.

In terms of educational outcomes, the lack of goals often set for multilingual education (e.g., the appreciation of diversity and intercultural competence) was not reflected in the effectiveness concepts at all based on the review. Regarding leadership, the aspects of cooperation, evidence-based management, and inclusion in decision making were prominent. Regarding the school climate and attitudes, the analyzed studies emphasized open-mindedness and tolerance toward diversity as well as a contemporary learner-centered approach to teaching and learning (dialogical, cooperative, and interaction-based methods, flexibility and adjustability according to the students’ personal needs, and a culturally responsive approach to learning).

The overview of effectiveness factors, while placed into the conceptual framework, serves as useful guidance for policy makers and educational administrators dealing with languages in education. However, it is vital to keep in mind that the list of factors outlined here must be analyzed in a specific context with the goals of education in mind. Education, and how it functions, is affected by a huge array of interdependent variables, and, in multilingual education, the complexity is further increased by linguistic and cultural aspects [

14].

The results of this review should be read in the context of the methodology applied, First, the choice of search terms had implications on the results. Here, the terms ‘bilingual’ and ‘multilingual education’ were used as wider concepts of the researched phenomenon. However, in some countries or regions, other terms might be more common and, therefore, might not have shown up in the search results. For instance, in the USA, especially in certain regions, the term ‘dual-language education’ referring to additive bilingual programs has been adopted [

50].

Secondly, the search performed in the databases tends to limit the results to mainly journal articles. Due to this fact, we hypothesize that ethnographic studies [

10,

51], although rather few in number [

3], describing and analyzing the wider contextual factors shaping multilingual education were not accessible under the current search as these are typically published in a book format. Thirdly, a number of studies remained inaccessible due to access restrictions.

Overall, we propose that this overview will be useful for policy makers and educational administrators in planning, evaluating, or revising multilingual education. Future studies on multilingual effectiveness could focus further on discussing contextual (macro level) factors together with school-level factors. Our conceptual framework functions as a useful guide regarding what factors need to be accounted for.