Preschool Children’s Reasoning about Sound from an Inferential-Representational Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Representation and Reasoning: Basic Assumptions

Origin and Function of Representations

3. Embodiment’s Role in Preschool Children’s Reasoning

4. Children’s Reasoning

5. The Inferential-Representational Approach

6. The Inferential Approach as an Analytic Tool

7. Materials and Methods

7.1. Method of Analysis

7.2. Representations as an Epistemic Tool

7.3. Sample

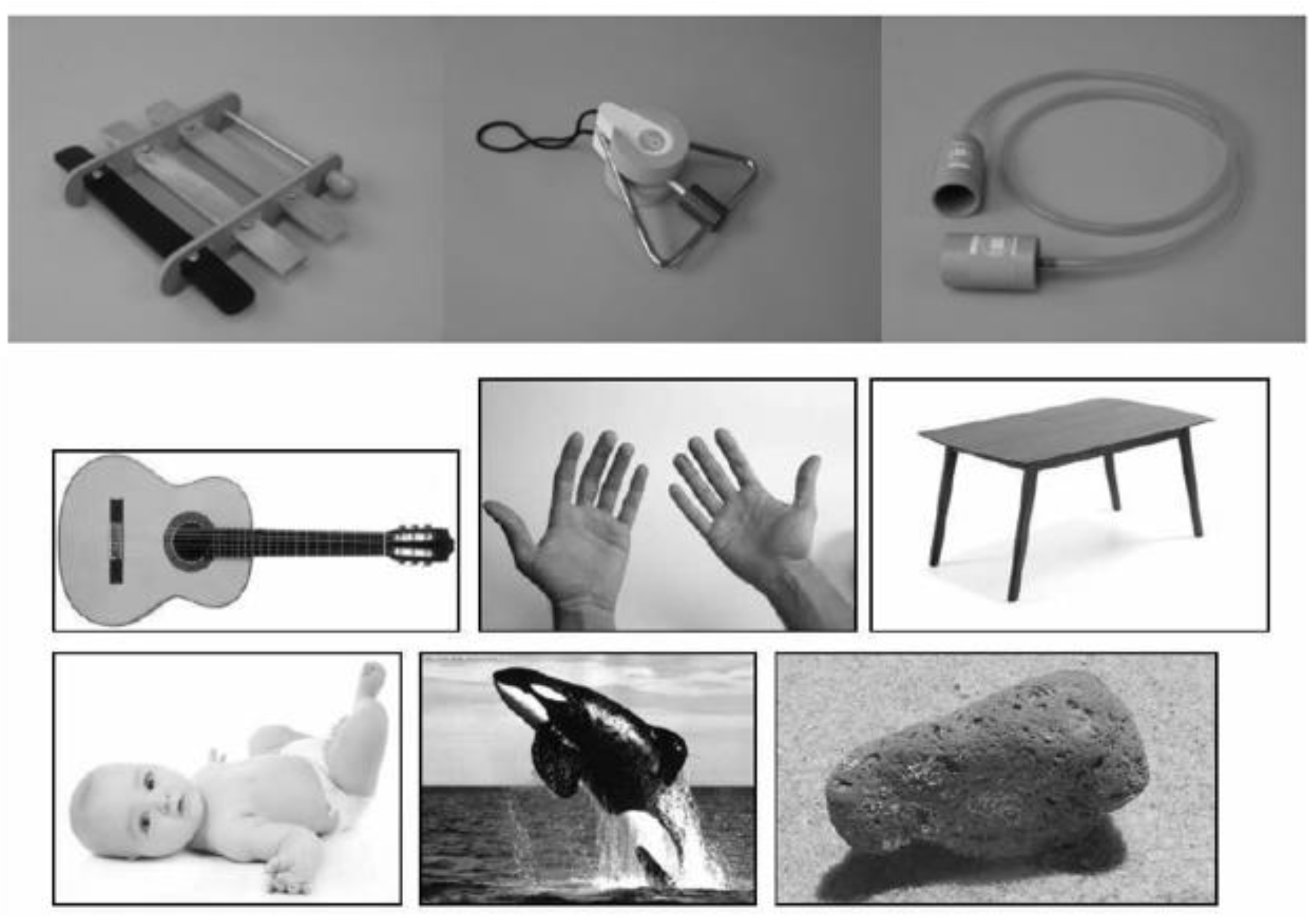

7.4. Instrument and Materials

7.5. Procedure

7.6. Categorisation

8. Results and Analysis

I = Interviewer; S1 = student (five years old)

I. Can you listen to the person on the other side of the hose telephone?

S1. Yes, I can.

I. How do you think that sound can reach there?

S1. The noise goes from this tiny hole that you have here until it reaches here. [pointing to the interior of the hose and the sound trajectory]

I. What happened to the sound of my voice? How does it got where you are?

S1. Because it goes like this. [pointing the hose from the middle up to where she is]

I. And what would happen if I fold and squeeze the hose? What will happen when I speak to you again?

A1. I would not listen.

I. You would not listen, why?

S1. Because you are covering it like this, so the noise gets stuck in there, and it will remain there. I cannot hear it.

I = interviewer, S2 = student (four years old)

I. I am going to show you some drawings or photos and you’re going to tell me if we can make sound with them (referring to the content of the drawing or photo)

S2. Nod his head.

I. What is this? [showing the card]

S2. A guitar.

I. What could we do with it to make a sound?

S2. Playing it.

I. How would you play it? If the guitar were real, which part would you touch to make a sound?

S2. Stretching the threads.

…

I. What is this? [showing a card with the drawing of a spider]

S2. A spider.

I. Do you think a spider can hear?

S2. No, she only catches bees or some little worm that flies toward his web.

I = Interviewer; S3 = Student (five-year-old girl)

I. If you put the earmuffs in your ears and I play the triangle, do you think you could listen to the sound?

S3. No.

I. No, why?

S3. Because the ears are covered while you play and after you take them off and you play again you will listen.

I. If I take off the earmuffs and play it again, I will listen, but if you have the earmuffs on with the ears covered you do not listen.

I. Do we try it?

S3. [student nods with her head]

I. Lean a little bit, so the triangle is not close to your body, okay now I am going to play. What happened?

S3. I listen to the sound. Because you play it, and the sound went like this. [The student points to the triangle and then points to the string that holds it]

I. Oh, because I play it, you think the sound went like this, how did it move?

S3. Through the strings

I. Through the strings. Where did the sound travel?

S3. Up to the ears, it went to my ears

I. It went to the earmuffs and then to your ears. Why do you listen to it when it reaches your ears?

S3. They must have holes. [referring to the earmuffs]

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hadzigeorgiou, Y. Young children’s ideas about physical science concepts. In Research in Early Childhood Science Education; Trundle, K.C., Sackes, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 67–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hrepic, Z.; Zollman, A.D.; Rebello, S. Identifying students’ mental model of sound propagation: The role of conceptual blending in understanding conceptual change. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top. Phys. Educ. Res. 2010, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejuan, A.; Bohias, X.; Jaén, X.; Periago, C. Misconceptions about sound among engineering students. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2012, 21, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. Las Explicaciones Causales; Barral: Barcelona, Spain, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Driver, R.; Squires, A.; Ruschworth, P.; Wood-Robinson, V. Dando sentido a la ciencia en secundaria: Investigaciones sobre las ideas de los niños; Antonio Machado Libros: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mazens, K.; Lautrey, J. Conceptual change in physics: Children’s naïve representations of sound. Cogn. Dev. 2003, 18, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshach, H.; Schwartz, J.L. Sound stuff? Naïve materialism in middle-school students’ conceptions of sound. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2006, 28, 733–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözen, M.; Bolat, M. Determining the misconceptions of primary school students related to sound transmission through drawing. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Olmedo, C.; Gallegos-Cázares, L.; Calderón-Canales, E. Formación de representaciones intuitivas acerca del sonido en niños de preescolar. Rev. Educ. 2018, 381, 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Canales, E.; Gallegos-Cázares, L.; Flores-Camacho, F. Sound representations in preschool studens/Las representa-ciones del sonido en estudiantes de preescolar. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2019, 42, 952–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartofsky, M.W. Models: Representations and the Scientific Understanding; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, D. Mental representations from the bottom up. Synthese 1987, 70, 23–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damerow, P. Abstraction and Representation: Essay on the Cultural Evolution of Thinking; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dretske, F. Experience as representation. Philos. Issues 2003, 13, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, J.I. Learning beyond the body: From embodied representations to explicitation mediated by external representations. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2017, 40, 219–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.Z. Missed Connections: A connectivity-constrained account of the representation and organization of object concepts. In The Conceptual Mind, New Directions in the Study of Concepts; Margolis, E., Laurence, S., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 79–115. [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou, L.W. Grounded cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 617–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papafragou, A. The representation of events in language and cognition. In The Conceptual Mind, New Directions in the Study of Concepts; Margolis, E., Laurence, S., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 327–345. [Google Scholar]

- Burr, C.; Jones, M. The body as laboratory: Prediction-error minimization, embodiment, and representation. Philos. Psychol. 2016, 29, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.A.; Foglia, L. Embodied cognition. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/embodied-cognition/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Lozada, M.; Carro, N. Embodied action improves cognition in children: Evidence from a study based on piagetian conservation task. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemirovsky, R.; Rasmussen, C.; Sweeney, G.; Wawro, M. When the classroom floor becomes the complex plane: Addition and multiplication as ways of bodily navigation. J. Learn. Sci. 2012, 21, 287–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impedovo, M.A.; Delserieys-Pedregosa, A.; Jégou, C.; Ravanis, K. Shadow Formation at Preschool from a Socio-materiality Perspective. Res. Sci. Educ. 2017, 47, 579–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin-Meadow, S.; Beilock, L.S. Action’s influence on thought: The case of gesture. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherin, L.B.; Krakowsky, M.; Lee, R.V. Some assembly required: How scientific explanations are constructed during clinical interviews. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2012, 49, 166–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Camacho, F.; Gallegos-Cázares, L. Partial possible models: An approach to interpret students’ physical representation. Sci. Educ. 1998, 82, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D. What is scientific thinking and how does it develop? In Blackwell Handbook of Cognitive Development; Goswami, U., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 371–393. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, D.; Sodian, B.; Koerber, S.; Schwippert, K. Scientific reasoning in elementary school children: Assessment and relations with cognitive abilities. Learn. Instr. 2014, 29, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meindertsma, H.B.; Van Dijk, M.W.G.; Steenbeek, H.W.; Van Geert, P.L.C. Assessment of preschooler’s scientific reasoning in adult-child interactions: What is the optimal context? Res. Sci. Educ. 2014, 44, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, C. The development of scientific reasoning skills. Dev. Rev. 2000, 20, 99–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, C. The development of scientific thinking skills in elementary and middle school. Dev. Rev. 2007, 27, 172–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D.; Garcia-Mila, M.; Zohar, A.; Andersen, C.; White, H.S.; Klahr, D.; Carver, M.S. Strategies of Knowledge Acquisition. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child. Dev. 1995, 60, 1–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauble, L. The development of scientific reasoning in knowledge-rich contexts. Dev. Psychol. 1996, 32, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hast, M. Children’s reasoning about rolling dawn curves: Arguing the case for a two-component commonsense theory of motion. Sci. Educ. 2016, 100, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M. An inferential conception of scientific representation. Philos. Sci. 2004, 71, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M. Scientific representations: Against similarity and isomorphism. Int. Stud. Philos. Sci. 2003, 17, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contessa, G. Scientific representation, interpretation, and surrogative reasoning. Philos. Sci. 2007, 74, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pero, F.; Suárez, M. Varieties of misrepresentation and homomorphism. Eur. J. Philos. 2016, 6, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuuttila, T. Models, representation, and mediation. Philos. Sci. 2005, 72, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuuttila, T. Modelling and representing: An artefactual approach to model-based representation. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. 2011, 42, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuuttila, T.; Boon, M. How do models give us knowledge? The case of Carnot’s ideal heat engine. Eur. J. Philos. Sci. 2011, 1, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carey, S. The origin of concepts. In Oxford Series in Cognitive Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth-Cohen, A.L.; Wittman, C.M. Aligning coordination class theory with a new context: Applying a theory on individual learning to group learning. Sci. Educ. 2017, 101, 333–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Ages | Ideas about Sound |

|---|---|---|

| Piaget (1973) | 4–5 5–6 7–10 11–15 | Sound is something that remains in its place. Sound is something that comes out of an object toward the ear and returns to the object. Sound moves in a straight line in all directions. Sound expands and travels through the air. |

| Driver, Squires, Ruschworth and Wood-Robinson (1994) | 4–16 | Sound is produced by the actions that subjects make over objects. Sound is a part of objects. Sound travels through the air. |

| Mazens and Lautrey (2003) | 6–10 | Sound cannot pass through solid matter. Sound passes through materials (if they have holes). Sound passes through materials that are not too strong. Sound is associated with the idea of vibration. |

| Eshach and Schwartz (2006) | 13–14 | Sound has substantial characteristics. Sound can push another object. Sound can be contained inside an object. Sound can be added to another sound. |

| Sözen and Bolat (2011) | Basic education | Sound travels through vibration and causes particles to move. Sound is heard through vibration and matter. |

| Delete for review (2018) | 5–6 | Sound has object properties. Sound is related to vibrations, but it is not possible to explain further. |

| Delete for review (2019) | 4–6 | Sound is within objects. Sound depends on a subject’s actions and can be perceived because we have ears. Sound bounces in materials. Sound requires space to propagate. |

| Factor to Determine from Representations | Determination Process |

|---|---|

| I. Intentionality | Questions and answers aligning. Example: “How you can produce sound?” If I hit with a stick |

| II. Elements of interpretation: (a). Embodiment-base ideas (b). Daily experience | Direct expressions of a process perception and involved organs in the perception. Example: “It can be hear because you have ears.” Expression that refers to some type of observation, self-observation or from others. Example: “The strong sound can be heard even with the ears covered.” |

| III. Sign-materials expressions | Constricted expressions from drawings and objects. Example: “The sound stays in the hose.” |

| IV. Representation | Representation elements’ integration. Example: “The sound travel in the air.” |

| V. Inferences | Expressions that indicate a supposition or explanation. Example: “If something is covered with a box then the sound is trapped.” |

| VI. Rules of coordination | Expressions of corroboration. Example: “The sound bounces off the hose because I don’t hear it anymore.” |

| Epistemic Tools | |

|---|---|

| T1 | Sound is a substantial entity that can be perceived through the ear. |

| T2 | Sound is in objects (people) and can be produced by action from them. |

| T3 | Sound is a substantial entity that requires a space to travel. |

| T4 | Sound is produced and transmitted differently depending on the materials. |

| T5 | For a sound to last long, the action that produces it must be repeated. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gallegos-Cázares, L.; Flores-Camacho, F.; Calderón-Canales, E. Preschool Children’s Reasoning about Sound from an Inferential-Representational Approach. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040180

Gallegos-Cázares L, Flores-Camacho F, Calderón-Canales E. Preschool Children’s Reasoning about Sound from an Inferential-Representational Approach. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(4):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040180

Chicago/Turabian StyleGallegos-Cázares, Leticia, Fernando Flores-Camacho, and Elena Calderón-Canales. 2021. "Preschool Children’s Reasoning about Sound from an Inferential-Representational Approach" Education Sciences 11, no. 4: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040180

APA StyleGallegos-Cázares, L., Flores-Camacho, F., & Calderón-Canales, E. (2021). Preschool Children’s Reasoning about Sound from an Inferential-Representational Approach. Education Sciences, 11(4), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040180