Outstanding Primary Leadership in Times of Turbulence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Context for Leadership

2. Methodology and Methods

2.1. Context of the Study

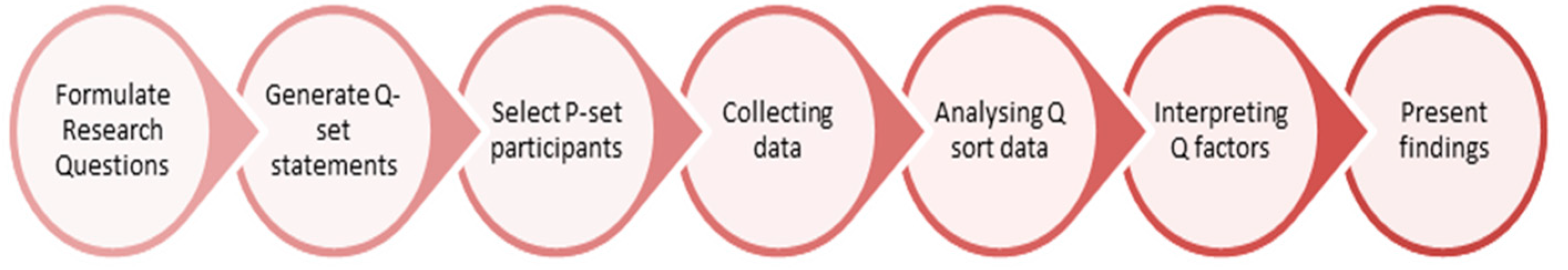

2.2. Methods and Analysis

2.3. Participants

3. Findings

3.1. Most Agreed Characteristics of Outstanding Leadership

Every school is different and so how one school does it might be different to another school because of the context of the school, the site, staff makeup, (staff cannot come in COVID whilst due to size of schools others can open).

The staff and the community as a whole had confidence that someone there was making the decisions and driving the thing. It was most important that we all had that sense of we know where we are going and why.

We needed to bring the school community along with us……that we were acting with integrity with the best interests of everyone at heart really. We have a really good sense of school community here and that level of trust we already had, was built on, that it was essential it was there (Leader 4).

It is so important that we develop a culture across the school not just the children but for adults as well where we see ourselves as learners and we encourage initiatives, that we encourage people to develop themselves.

Their emotions, their fears, their backgrounds, lots and lots of people carry background stuff at the moment, to do with family, bereavement and concerns and it all comes in a big melting pot.

Working at teams enables that to happen. Being in it together gives people ownership rather than being directed from the top. With staff working remotely you are really relying on teams to work effectively and to collaborate with one another (Leader 2).You may not think and feel the same as the person next to you but we have to take care of everyone… We have got to bring everyone along and even though you may not be anxious we are implementing this because A, B, C are anxious so we have to do it for their sake. It is important that we didn’t leave anyone behind (Leader 4).

Being there in the thick of it, alongside everyone, doing the same things as everyone else really. I think it much easier in a small school community to be one of the communities doing the same as everyone else.

3.2. Most Disagreed Characteristics of Outstanding Leadership

We just limped through with the budget. If there were additional costs they just had to be met… you had to let go of that and release the usual anxiety you have around that, there was just so much else you had to focus on.

I said very early on to the finance committee of our governing body that there are cost centres that are just going to have to go over, there is nothing we can do we just have to have these spends (PPE, extra cleaning) we just have to sit tight and wait to see what comes out the other end.

We have to keep an eye on the finances definitely but there are going to be, what is a contingency for but a rainy day and I would suggest it is a rainy day at the moment.

There has been a complicit understanding, with for example SATs off the table that we cannot work to the same agenda. Standards are always important, no right minded professional would say not, but perhaps the way the whole teaching body is held to account, that is a sort of thing we could suspend for a year.

You have to be pragmatic, no way we can really monitor closely outcomes, what children are doing… is unrealistic to think we are going to do it in the same way as we can do it in the classroom…if a child is involved in a live teaching or seems to be on the screen, they might be but actually their engagement might be very limited, they might just have the screen on, how do we know they are actually engaging so it’s going to be very difficult to measure how well they are getting on.

We are assessing our children continuously through this virtual existence of ours but what we will put in place, we will catch up, but it is the children’s emotional health and wellbeing that is really important.

Although we were engaging in remote learning what wasn’t important about that was the monitoring the meticulous outcomes of that it was the fact that they were engaged… that things were ticking over. I was monitoring engagement, we were doing all the usual things, phone calls home and all of that but the monitoring was a completely different kind to what would be our bread-and-butter standards monitoring.

There was no question of monitoring that performance in any way. We knew and believed that they were doing the best that they could and that was good enough. That was good enough for me that people were turning in, despite their levels of anxiety, they were doing their job to the best of their ability…so managing performance goes out the window in that scenario I am afraid.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, L.; Riley, D. School leadership in times of crisis. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2012, 32, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. COVID-19-school leadership in crisis? J. Prof. Cap. Community 2020, 5, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M. COVID 19-Leadership in crisis. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, E.J.; Marcus, L.J.; Joseph, M.; Henderson, J.M. Crisis leaders? Prepare to lead when it matters most. Lead. Lead. 2019, 2019, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, S.; Dulsky, S. Resilience, reorientation, and reinvention: School leadership during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 637075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofsted COVID-19 Series: Briefing on Schools. 2020. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/933490/COVID-19_series_briefing_on_schools_October_2020.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Fullan, M. Change Forces: The Sequel; Falmer Press: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C.; Sammons, P. Successful School Leadership; Education Development Trust: Reading, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, P.; McKenzie, M.; Mercieca, D.; Mercieca, D.P.; Sutherland, L. Primary head teachers’ construction and re-negotiation of care in COVID-19 lockdown in Scotland. Front. Educ. 2021, 617869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, I.E. Learning and growing: Trust, leadership, and response to crisis. J. Educ. Adm. 2017, 55, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, P.; Rea, S.; Hill, R.; Gu, Q. Freedom to Lead: A Study of Outstanding Primary School Leadership in England; National College for Teaching and Leadership: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon, J.K.; Howard, C.; Holt, J. Outstanding leadership in primary education: Perceptions of school leaders in English primary schools. Manag. Educ. 2019, 34, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beauchamp, G.; Hulme, M.; Clarke, L.; Hamilton, L.; Harvey, J.A. ‘People miss people’: A study of school leadership and management in the four nations of the United Kingdom in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2021, 49, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlo, S. Mixed method lessons learned from 80 years of Q-methodology. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2016, 10, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Educational Research Association (BERA) Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research, 4th ed.; British Educational Research Association: London, UK, 2018.

- Stephenson, W. General Theory of Communication. Operant Subj. 2014, 37, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willig, C.; Stainton-Rogers, W. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Seven Strong Claims about Successful School Leadership; NCSLCS: Nottingham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C.; Sammons, P.; Hopkins, D.; Harris, A.; Leithwood, K.; Qing, G.; Brown, E. 10 Strong Claims about Successful School Leadership; NCSLCS: Nottingham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Harris, A.; Hopkins, D. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2019, 40, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.; Whelan, F.; Clark, M. Capturing the Leadership Premium; NCSLCS: Nottingham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, T. Leadership and Management Development in Education; Sage: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- NCSL (National College for School Leadership). What We Know about School Leadership; NCSL: Nottingham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon, J.K. Senior managers’ perspectives of leading and managing effective, sustainable and successful partnerships. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2013, 41, 736–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headteachers’ Standards 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-standards-of-excellence-for-headteachers/headteachers-standards-2020 (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Tschannen-Moran, M. Trust Matters: Leadership for Successful Schools; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A.; Fullan, M. Professional Capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Netolicky, D.M. School leadership during a pandemic. J. Prof. Cap. Community 2020, 5, 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Ofsted Guidance School Inspection Handbook. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/school-inspection-handbook-eif/school-inspection-handbook (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Gainey, B. Crisis management’s new role in educational settings. Clear. House 2009, 82, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clear strategic vision and communicated effectively to others (1) | Passion for providing world class education (2) | Strategic vision based on shared values (4) |

| Inspirational leader who leads by example (5) | High levels of trust between leaders and their stakeholders (7) | Ability to bring out the best in people and inspire others (8) |

| Power and accountability shared and distributed amongst members of leadership team (10) | Ability to foster discussion and debate (11) | High expectations of all members of staff and pupils/learners (13) |

| An open culture of learning where excellence in all aspects of achievement are celebrated (14) | Foster collaboration, partnerships and shared decision-making (16) | Values and vision developed and owned by all members of staff and governors (17) |

| Setting ambitious targets and maintaining clear focus on achieving financial as well as educational/academic goals (18) | Empowering others to achieve ambitious targets (19) | Meticulous monitoring of outcomes for pupils/learners (20) |

| Reconciling opposing points of view and summarising agreed points to leadership teams (21) | Taking decisive action to address poor performance of staff teams e.g., senior, middle leaders, curriculum teams, pastoral support (22) | Taking difficult decisions and communicating them honestly to those affected (23) |

| Balancing financial constraints with aspirational educational ambitions (3) | Maximising talent in the team and deploying talent effectively in the organisation (9) | Engaging the local community in developing a shared vision for educational provision in the area (6) |

| Develop entrepreneurial and innovative approaches to improve education (12) | Developing an aspirational culture in the school/college and local community (15) |

| Most Agree and by Rank Order | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Original Study | High expectations of all members of staff and pupils (13) | Maximising talent and deploying it effectively in the organisation (9) | Taking decisive action to address poor performance of staff (22) | Inspirational leader who leads by example (5) | Ability to bring out the best in people and inspire others (8) |

| Leader 1 | Clear strategic vision and communicated effectively to others (1) | An open culture of learning where excellence in all aspects of achievement are celebrated (14) | Taking difficult decisions and communicating them honestly to those affected (23) | Foster collaboration, partnerships and shared decision-making (16) | Values and vision developed and owned by all members of staff and governors (17) |

| Leader 2 | Values and vision developed and owned by all members of staff and governors (17) | High levels of trust between leaders and their stakeholders (7) | An open culture of learning where excellence in all aspects of achievement are celebrated (14) | Developing an aspirational culture in the school/college and local community (15) | Reconciling opposing points of view and summarising agreed points to leadership teams (21) |

| Leader 3 | Clear strategic vision and communicated effectively to others (1) | High levels of trust between leaders and their stakeholders (7) | Taking difficult decisions and communicating them honestly to those affected (23) | Foster collaboration, partnerships and shared decision-making (16) | Engaging the localcommunity in developing a shared vision for educational provision in the area (6) |

| Leader 4 | Clear strategic vision and communicated effectively to others (1) | Taking difficult decisions and communicating them honestly to those affected (23) | High levels of trust between leaders and their stakeholders (7) | Inspirational leader who leads by example (5) | Reconciling opposing points of view and summarising agreed points to leadership teams (21) |

| Most Disagree and by Rank Order | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Original Study | Passion for providing world class education (2) | Ability to foster discussion and debate (11) | Develop entrepreneurial innovative approaches to improve education (12) | Engaging local community in a shared vision for education in the area (6) | Reconciling opposing points of view and summarising agreed points (21) |

| Leader 1 | Meticulous monitoring of outcomes for pupils/learners (20) | Setting ambitious targets and maintaining clear focus on achieving financial as well as educational/academic goals (18) | Strategic vision based on shared values (4) | Taking decisive action to address poor performance of staff teams e.g., senior, middle leaders, curriculum teams, pastoral support (22) | Values and vision developed and owned by all members of staff and governors (17) |

| Leader 2 | Taking decisive action to address poor performance of staff teams e.g., senior, middle leaders, curriculum teams, pastoral support (22) | Balancing financial constraints with aspirational educational ambitions (3) | Maximising talent in the team and deploying talent effectively in the organisation (9) | Meticulous monitoring of outcomes for pupils/learners (20) | Setting ambitious targets and maintaining clear focus on achieving financial as well as educational/academic goals (18) |

| Leader 3 | Balancing financial constraints with aspirational educational ambitions (3) | Meticulous monitoring of outcomes for pupils/learners (20) | Taking decisive action to address poor performance of staff teams e.g., senior, middle leaders, curriculum teams, pastoral support (22) | Setting ambitious targets and maintaining clear focus on achieving financial as well as educational/academic goals (18) | Maximising talent in the team and deploying talent effectively in the organisation (9) |

| Leader 4 | Engaging local community in a shared vision for education in the area (6) | Develop entrepreneurial innovative approaches to improve education (12) | Balancing financial constraints with aspirational educational ambitions (3) | Taking decisive action to address poor performance of staff teams e.g., senior, middle leaders, curriculum teams, pastoral support (22) | Meticulous monitoring of outcomes for pupils/learners (20) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Howard, C.; Dhillon, J.K. Outstanding Primary Leadership in Times of Turbulence. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110714

Howard C, Dhillon JK. Outstanding Primary Leadership in Times of Turbulence. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(11):714. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110714

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoward, Colin, and Jaswinder K. Dhillon. 2021. "Outstanding Primary Leadership in Times of Turbulence" Education Sciences 11, no. 11: 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110714

APA StyleHoward, C., & Dhillon, J. K. (2021). Outstanding Primary Leadership in Times of Turbulence. Education Sciences, 11(11), 714. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110714