1. Introduction

Since the identification of HIV and AIDS in the early 1980s in Sub-Saharan Africa, a major challenge of health literacy education in countries such as Uganda has been that reproductive health and sexuality—key components of HIV and AIDS education—are considered culturally inappropriate topics for face-to-face discussion. In an article in Uganda’s national newspaper

New Vision, which featured children demanding that their parents, caretakers, and teachers more openly share accurate information about HIV and AIDS, a parent insightfully identified a critical “information gap”. As she explained, “Most of us parents are shy; there are issues like sex that we cannot talk to our children about. We have left the role to teachers but sometimes, (teachers) also do not (talk to children about issues like sex). The problem of information gap has led our children into problems” (Vision Reporter, 2015) [

1]. This paper, which extends our previous research on visual representations of HIV and AIDS (Becker-Zayas, Kendrick, and Namazzi, 2018 [

2]; Mutonyi and Kendrick, 2011 [

3]; 2010 [

4]), focuses on how this crucial information gap might be addressed within a classroom makerspace that engages participants in both the production and dissemination of HIV/AIDS public service announcements. Specifically, we address the question: “How might child-created billboards about HIV and AIDS help facilitate more open discussions between parents and children?”

Uganda, lauded for its sharp reduction in HIV and AIDS infections over the past several decades, has seen that trend begin to reverse, with AIDS rates rising (Kron, 2012) [

5]. In 2015, the United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) [

6] reported that 150,000 children in Uganda, the majority of which are girls, accounted for many of the new infections. Although paternal aunts (Ssengas), maternal uncles (Kkojjas), and paternal grandparents have traditionally been considered the custodians of sexual knowledge and have the obligation of talking to their nieces, nephews, granddaughters, and grandsons about issues of sexuality, these relationships have shifted because extended family members are now too distant geographically to carry out these roles. Within this context, there are multiple barriers to discussing issues related to sexuality and HIV and AIDS, as referenced in the

New Vision article. In this study, we set out to explore how a makerspace designed to engage children in communicating HIV and AIDS knowledge and understandings through billboard production and dissemination might help facilitate more open discussions between adult caregivers and children.

Uganda has a long history as a maker culture, with traditions passed down from one generation to the next. Young children learn to use local materials such as corn cobs and husks, wooden spools, wire, plastic bags and bottles, and environmental materials (e.g., pebbles, sticks, seeds, banana fibres) for designing dolls, soccer balls, toy cars, and games, among other productions. Adults engage in a wide range of making as well, including the creation of art, crafts, furniture, games, and decorative objects using beads, soapstone, wood, cloth, and metal, among other materials. Across the country, making and designing have deep historical roots in social and cultural meaning-making, community values, and indigenous knowledge (Nwokah and Ikekeonwu, 2007) [

7]. In this study, we designed a makerspace that brings together these traditional values and practices with school-based art, science, and health/sex education in connection with public health by engaging participants in the production and dissemination of HIV and AIDS billboards, a ubiquitous aspect of Uganda’s national health education efforts. Although there is a dearth of empirical research on makerspaces in general (Sheridan et al., 2014) [

8], an opportunity to study a makerspace in a classroom in Uganda has the potential to offer new insights into the prospects of transforming traditional cultural practices into meaningful pedagogies in formal learning spaces.

HIV and AIDS education is mandated curriculum in Uganda, but the effectiveness of how this curriculum is implemented has been called into question. In a United States Agency for International Development (USAID) survey of 60 Ugandan districts in 2014, it was found that only 38.9% of 15- to 24-year-olds could correctly identify ways of preventing the sexual transmission of HIV and reject major misconceptions about HIV transmission (Ministry of Health, Uganda, 2012) [

9]. As emphasized previously, a complicating factor is that, despite national campaign messages intended to stimulate public dialogue about HIV and AIDS, the open discussion of the sexual practices that contribute to the transmission of HIV is often cloaked in silence. Over the past several decades, Uganda has implemented a number of innovations in HIV and AIDS education, particularly through extra-curricular clubs and activities involving drama, music, and visual art. Our previous research focusing on secondary students’ understandings of HIV and AIDS has shown that alternative forms of representation such as the visual (Mutonyi and Kendrick, 2010 [

4]; 2011 [

3]) and the use of metaphor (see, for example, Mutonyi, Nielsen, and Nashon, 2007 [

10]; Mutonyi, Nashon, and Nielson, 2010 [

11]) can enable students to both transcend and respect cultural sensitivities in communicating information about sexual issues (see also Mitchell, 2011) [

12]. The premise of our current study is that there may also be considerable potential for using multimodal forms of representation in makerspaces with younger populations in order to generate more open dialogue with adults about culturally sensitive knowledge.

1.1. Theoretical Perspectives

In this study, we draw primarily on Sheridan et al.’s (2014: 507) [

8] notion of makerspace as a collaborative space for “developing an idea and constructing it into some physical or digital form”. According to Marsh et al. (2018) [

13], this definition can include the provision of everyday classroom makerspaces that, as Johnson et al. (2015) [

14] point out, have the potential to empower young people to bring about change in their own communities. In our project, children are positioned as change agents, knowledge producers, and disseminators, creating public service announcements in the form of HIV/AIDS billboards to enhance the communication of difficult knowledge with parents.

We conceptualize makerspaces as part of a community of practice characterized by a “shared use of space, tools, and materials; shifting teaching and learning arrangements; individual and collective goals; and emergent documentation of rules, protocols, and processes for participation and action work together to form each community of practice with its own particular features” (Sheridan et al., 2014:509) [

8]. Because makerspaces are influenced by practices within communities, cultures, and institutions such as schools, how they are taken up and operate will differ across contexts. The commonality of these spaces is that all involve making/developing an idea into some physical form (Sheridan et al., 2014) [

8].

In designing our makerspaces as learning environments, we drew on Hetland et al.’s (2013) [

15] studio structures, which include: (1)

demonstration-lectures, whereby teachers or facilitators set open challenges, show exemplars, and demonstrate key processes; (2)

students-at-work creating art and receiving in-the-moment instruction; (3)

critiques that pause the making process for reflection and feedback; and (4)

exhibitions, where students’ work is shared with important audiences beyond the classroom or studio space. Our design process was iterative: it began with the challenge of how children can communicate and discuss HIV/AIDS information with their parents, involved drafting and revising ideas both verbally and visually, and was followed by the creation of a public billboard shared during exhibition to engage parents in a discussion.

Our makerspace was designed to enable learners to use multiple modes (visual and linguistic) to create HIV and AIDS billboards that represent their points of inquiry, knowledge, and interpretations of HIV and AIDS information and experiences, including the important messages they wished to communicate to members of their community. We position the billboard making as a multimodal literacy practice situated within expanded notions of literacy as social practice (Heath, 1983 [

16]; Kendrick, 2016 [

17]; Street, 1984 [

18] which we bring together with Rose’s (2016) [

19] visual methodology.

1.1.1. Multimodal Literacies

Aligned with scholars in New Literacy Studies (see, for example, Baynham, 1995 [

20]; Heath, 1983 [

16]; Street, 1984 [

18]), we conceptualize literacy as not only a skill to be learned but a socially constructed and locally negotiated practice. We consider literacy as multiple and varied across time, place, and space, contested in unequal relationships of power. Like many scholars and educators in literacy education, however, we also recognize that language, whether written or spoken, is only partial to the process of making meaning (Kress, 1997 [

21]; Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996 [

22]), and that simultaneous modes such as images, gestures, and speech afford different communicative resources for makers.

Our focus on multimodal literacies places emphasis on the use of modes and their affordances in the process of making. Multimodality in general draws on social semiotics to explain and understand how signs are used to “produce and communicate meanings in specific social settings” (Kress and van Leeuwen, 1996:264) [

22]. As Kress (1997) [

21] points out, signs communicate the here and now of a social context while at the same time representing the resources makers have available from the world around them. These diverse resources are grounded in the material and social conditions of people’s lives; their preferred modes of learning and participating in social, spiritual, and cultural events; their health and healing practices; and their child-rearing practices (Smythe and Toohey, 2009) [

23]. When makers are given opportunities to draw on their full multimodal repertoires, learning becomes generative because of the mode-meshing/synesthetic opportunities inherent in negotiating meaning across languages, sign systems, and modes (see, for example, Kendrick, 2016) [

17]. As Kress (1997) [

21] emphasizes, different modes give rise to different ways of thinking and inquiring because humans constantly translate meaning from one mode to another. We see makerspaces as spaces of inquiry and new learning, spaces that provide opportunities for makers to think and create in all modes.

1.1.2. Visual Methodologies

The billboard project foregrounds the visual as a meaning making resource. We find Rose’s (1996 [

24], 2016 [

19]) conceptualization of meaning production in cultural geography especially helpful in understanding how visual modes work. Rose takes a critical approach, emphasizing that geographers never take visual representations “as straightforward mirrors of reality”; rather, “the meanings of an image are understood as constructed through a range of complex and thoroughly social processes and sites of signification” (1996:4) [

24]. As she points out, the focus on the complexity of “social processes and sites of signification” is both material and cultural, “forming a network of producers, transmitters, technologies, audiences, exhibitors, media, curators, sites, consumers and critics—to name just some of the actants in this network—all of which make sense of any particular image through complicated, multiple and possibly contradictory codes of signification” (1996:4) [

24].

Rose (2016) [

19] moves from this broad conceptualization of meaning production towards an interpretation of particular images by focusing on the most important actants within this network: producers, texts, circulation, and audiences. Producers are the people and equipment involved in making the image; text refers to the image itself; circulation is about how an image travels beyond its site of production, affected by a wide range of social, cultural, political, and economic considerations; and audience constitutes all those who look at the image. Visual analysis requires understanding how meaning is produced at each of these four sites and in relation to three interconnected modalities: the social, the compositional, and the technological (Rose, 2016) [

19]. The social is the organization of social institutions, social difference, and social subjectivities; the compositional refers to an image’s specific material qualities (for example, content, color, and spatial organization); and the technological is the equipment involved in the image. Rose carefully considers the intersections and relationships across these three modalities (technological, compositional, and social) and four sites of meaning-making (production, image, circulation, and audiences) in relation to the uses and meanings of images. In this study, we are interested in the interrelationships across these sites, with a particular emphasis on parents and caregivers as audience and the ways in which they take up the viewing of the billboards created by their children.

2. Materials and Methods

Our study included 34 Grade 5 students and their parents/caregivers. The students attended a rural Ugandan residential primary school. As pre-adolescent 9- and 10-year-olds, Grade 5 students are at a critical age for learning about HIV and AIDS and issues of sexuality. In addition to mandated HIV and AIDS curriculum, outside of the classroom in public spaces in their villages and communities, students are also exposed to various public service announcements on the radio and television, on billboards, and via other modes such as dramatic performance as part of a national campaign strategy to prevent HIV and AIDS.

The study was conducted by a research team that consisted of two Ugandan researchers and two Canadian researchers. One of the two Ugandans is a former teacher; both are educators and one is an HIV/AIDS educator. Both are members of the community where the research was conducted, are multilingual and share a language with the children in the study. One of the Canadian researchers is a former teacher who has taught in both Canada and East Africa, and has been conducting multimodal research in East Africa over the past 15 years. The second Canadian is an educator and researcher who works with young children.

As noted earlier, in designing our makerspace we drew on Hetland et al.’s (2013) [

15] studio structures, which include: (1) demonstration-lectures, (2) students-at-work, (3) critiques, and (4) exhibitions. In the demonstration-lectures, students’ knowledge about HIV and AIDS was first elicited as part of a class discussion. We used a projector and screen to engage students in a discussion about a series of HIV and AIDS billboards commonly seen in their region. Students were asked to interpret the billboards, which we positioned as demonstration texts. They worked in groups of 5–6 to collaboratively share their experiences and understandings of the texts, including how features, colors, language, and design were used. There were no specific morals or values communicated by adult facilitators.

In students-at-work creating art, we provided a variety of visual art-making materials (e.g., drawing pencils, colored pencils, felt markers, crayons, paper, and scissors) as tools for addressing the problem of how to communicate knowledge and understandings of HIV/AIDS with diverse audiences (their parents, caregivers, teachers, and classmates). The students were free to select any materials for creating and to collaborate in creating their billboards; however, they were aware that they would be sharing and discussing the billboards with their parents, and that the topic was sensitive and private in nature. They also understood their billboards would be shared with an international audience as part of our research project. When they started the creation process, they took a very serious and individual approach by choice. We respected their decision-making as important to their own making processes.

The critique/feedback aspect of the design involved the teacher and researchers circulating and commenting during the making process. The exhibition, which focused on audience engagement/parent involvement, was particularly critical to our research question and the design of the project. The participants shared their texts with their parents and caregivers during a weekend family visiting day at the school. The students were not coached on what or how they should share.

To understand how the billboard texts were received within the public exhibition space, we conducted follow up interviews (in English and home languages) with the parents/caregivers (see

Appendix A) and child participants (see

Appendix B). These interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed by a member of our research team. Our analysis of the transcripts centered on identifying “passages with similar topics” (Meuser and Nagel, 2009:35) [

25] as thematic units. We followed Meuser and Nagel’s six-step analysis (1. transcription, 2. paraphrasing, 3. coding/identifying themes, 4. thematic comparison, 5. scientific conceptualization/establishing categories, and 6. theoretical generalization). Our procedures were recursive and collaborative. We listened to and reread transcripts and coded/paraphrased excerpts multiple times in order to identify the most salient themes in relation to our focal question. Our goal was to understand how producing and sharing texts about HIV and AIDS might afford opportunities to enhance the communication of difficult knowledge between children and their parents/caregivers.

Our collaborative analysis of the billboard texts used visual analysis (see for example, Mitchell, 2011 [

12]; Rose, 2016 [

19]; Warburton, 1998 [

26]) to identify patterns and themes within sites of meaning making and across the collection. We sought to surface and make visible the social practices, knowledge, and issues associated with HIV and AIDS that were recontextualized in the billboards created by the children. We draw on Warburton’s (1998) [

26] analytic framework to identify the narrative threads evident in the billboard messages. This process began with describing the visual and textual material evident in the artifact, including who and what are represented (initial description). We then focused on explaining what the billboard might mean to viewers, including larger systemic connotations (immediate and systemic connotations). Finally, we established narrative threads as a way of synthesizing the meaning potentials across Rose’s (2016) [

19] sites of production, image, circulation, and audience. The children’s written descriptions of their billboards guided our analysis.

In the next section, we present a synthesis of the billboard drawings as artifacts to illustrate the perceptions, experiences, and issues typical of the collection as a whole. We then show through interview excerpts the patterns evident in our participants’ responses to sharing and discussing the billboard drawings during the family visiting day exhibition. It is important to note that on the school visiting day, it was primarily mothers who attended. Where both mothers and fathers attended together, fathers tended to take a more passive stance, with the expectation that mothers engage in the discussion with the children. Pseudonyms for the children and parents are used throughout. Where we initially provide the name of participants, we indicate in brackets whether they are boys or girls (our identification) or mothers or fathers.

3. Results

3.1. Billboard Drawings

Across the collection of billboard drawings, we note four salient patterns linked to the students’ designs and inquiries into their own social and cultural knowledge and relationship to the topic of HIV and AIDS. These patterns communicate personal messages through the inclusion of emotions, students’ names, diverse races, and the red AIDS ribbon as a symbol. Additionally significant is the relative absence of stigma and the depiction of distinct roles for males and females. First, emotions such as fear, despair, shame, desperation, determination, anger, loneliness, sickness, lust, and hope are central to the students’ messages. Second, many of the students chose to display their names prominently, sometimes multiple times on the same billboard, using color, hand-drawn fonts, and lines to express messages of both pride and identity. Third, the drawings portray different races, signaling that the students do not associate HIV and AIDS with one specific group of people. Finally, the red AIDS ribbon, which signifies “working together” to prevent HIV and AIDS, is often found next to a human figure, implying that that individual has the knowledge and power to prevent the spread of the disease. Moreover, although the stigma of the disease has long been a barrier to treatment and prevention, in the billboard drawings stigma was mostly absent from the images, captions, and students’ written explanations.

We foreground the depiction of male and female roles, as it was relatively universal in its pattern of male instigators and female decliners. Similar to the demonstration texts we shared during the first stage of the project, our participants’ descriptions and explanations of their billboards address a general audience (beyond just their parents and caregivers), often delivering decidedly gendered cautionary messages about men as instigators (i.e., proposing sex or marriage or offering gifts in exchange for sex or marriage) and women taking up the role of refusal. Such narratives are common in the national HIV and AIDS campaign and integral to how the community understands the virus. In all of the billboards depicting similar coercive exchanges (i.e., sugar daddy/gift-giving), the woman is depicted as refusing the gifts or proposals of sex and/or marriage, and the viewer is left to assume her wish has been honored and to learn that refusal is one way of evading the disease. Solicitation with gift offering most typically involved flowers, which underscores the sensitive local cultural knowledge that such an exchange indexes. In none of the drawings is the infected boy or man admonished for inappropriately offering gifts to the girl; instead, the man’s proposals are portrayed as natural or unproblematic, and the girl is responsible for refusing them. This recurrent scene suggests that children in this context are learning that girls are largely responsible for stopping the spread of HIV/AIDS—girls who, in many cases, have limited power in key areas of their lives that can play a part in HIV/AIDS transmission (e.g., poverty, which can be a driver of child marriage, and sexual violence). In the next section, we provide two illustrative examples of this pattern of male/female roles.

3.2. Two Illustrative Examples

Even though HIV and AIDS has devastated communities around the world, the narratives embedded in the child-produced billboards tend to be directed at local audiences and the HIV and AIDS public education campaign, for which the children themselves were already an audience. The gift-exchange scenarios, depictions of natural and domestic spaces in some of the billboards, as well as mentions of early marriage proposals all suggest that the intended audience for these drawings is a local one with shared cultural understandings and social practices, and for whom this ongoing public narrative (HIV and AIDS prevention) was recognizable and meaningful.

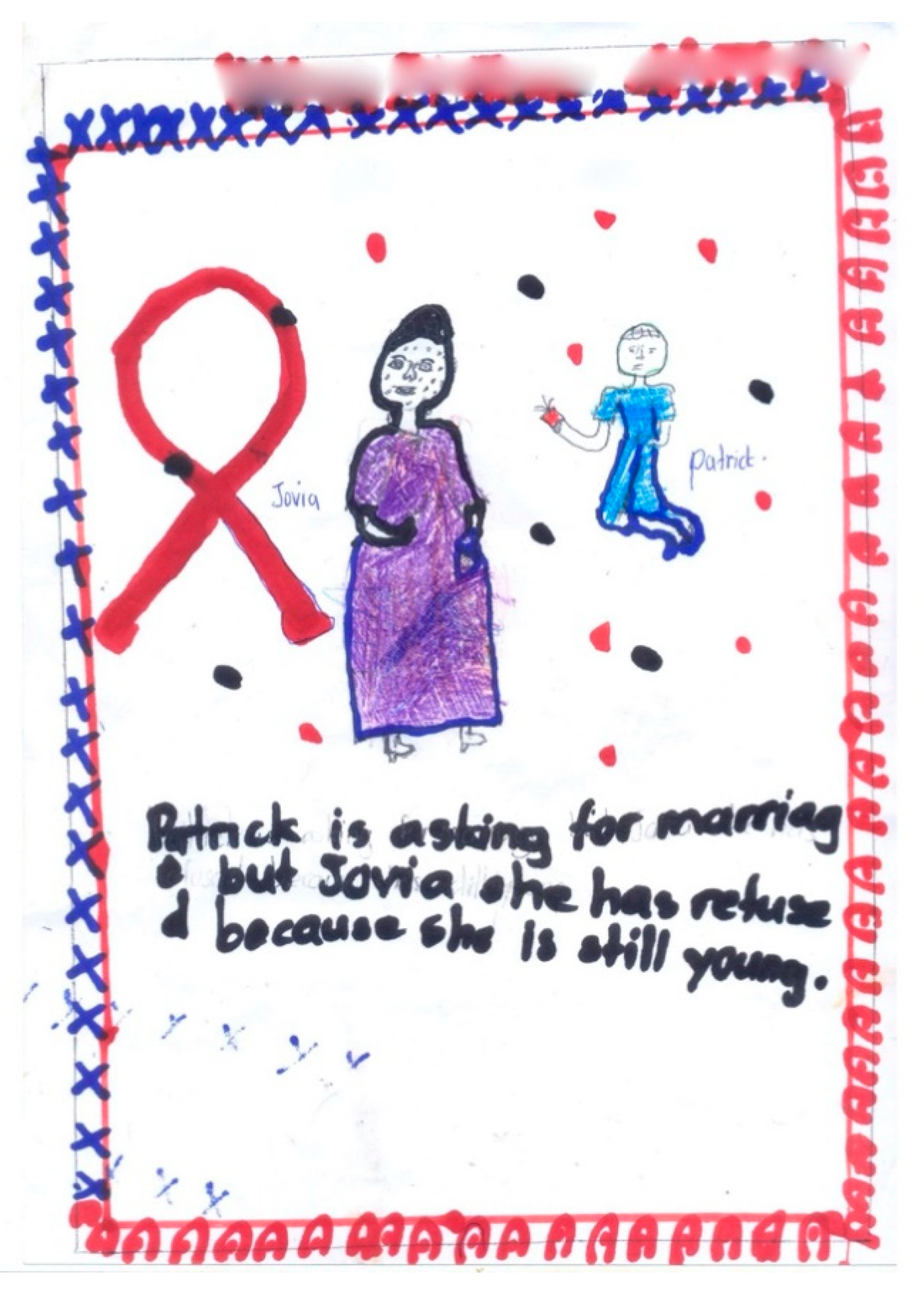

Cate’s (girl) billboard (

Figure 1), for example, depicts a girl in a purple dress with spots on her face addressing the viewer with a confident gaze. A boy in a blue jumpsuit kneels behind her, his body also facing the viewer, but his concerned expression is turned toward the girl. In his outstretched arm is a small red gift box. There is a large red AIDS ribbon next to the girl, measuring from her thigh to above her head. Both actors are labelled in blue pen. The billboard is bordered in a red line with blue Xs around one half and red AIDS ribbons around the other half. The author’s name appears three times at the top of the page: Twice in pencil (bold letters) and once in red marker, over one of the pencil versions. The caption reads: “Patrick is asking for marriage but Jovia she has refused because she is still young.” In the author’s note on the back of the drawing, we find the following: (The author’s name appears again [masked], bolded and underlined, with the following list)

- (1)

The message on my billboard is that about asking for marriage sex but Jovia refused to take the ring because Patrick has HIV/AIDS. On my drawing is a symbol of stopping HIV/AIDS.

- (2)

The drawing is about stopping HIV/AIDS because it can kill people.

- (3)

I want people to learn that HIV/AIDS is the killer disease that has no medicine.

This billboard maker uses perspective to emphasize the role of women and girls in preventing HIV and AIDS. Jovia is represented as being much larger than Patrick, although the text indicates that she is “still young”, and Patrick, who is proposing marriage, is shown as having a diminished physical presence. Jovia’s confident stance in the centre of the page, her calm and grounded facial expression, and her place beside a larger-than-life HIV and AIDS ribbon, work together to imply that the prevention of HIV and AIDS rests primarily with girls and women, and that they are fully capable of resisting transmission, a common message communicated by adults in the community.

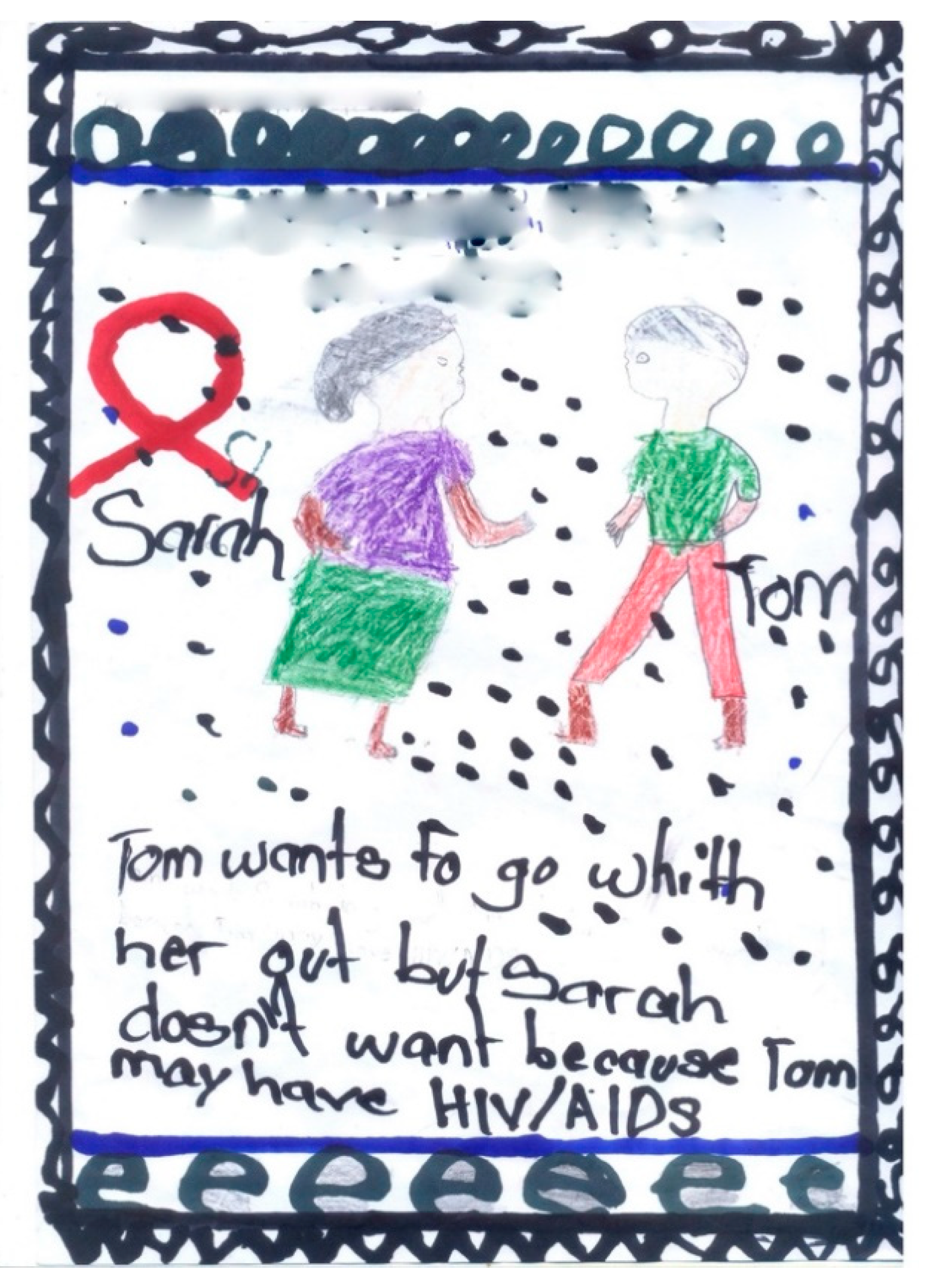

In Teddy’s (girl) billboard (

Figure 2), a man and woman stand facing one another in the upper half of the billboard. The man’s facial expression shows surprise, possibly anger, whereas the woman’s expression appears more determined, admonishing. She has one arm slightly raised, as if to emphasize her displeasure with his request (which we learn about in the caption). Their names (Sarah and Tom) float behind them amid a backdrop of black and blue dots. Behind Sarah and above her name floats a red AIDS ribbon, stretching from her mid-torso to the top of her head. The billboard is bordered with black and blue lines, with shapes and letters patterned around them. The maker’s name appears four times at the top of the page: twice in pencil, once in blue pen, and once in black marker (tracing over the blue pen). Her name is bolded in each instance. The caption reads: “Tom wants to go whith (sic) her out but Sarah doesn’t want because Tom may have HIV/AIDS.” The author’s note on the back of the drawing contains detailed remarks to clarify the message of the drawing, and the author’s wishes for her audience:

- (1)

My message is about a man who is telling Sarah to go with her [him] out but Sarah has refused to go with him because that man has HIV/AIDS.

That man got HIV/AIDS as a result of playing sex with an infected person.

People should not play sex with an infected person because they may get HIV/AIDS.

On my billboard there is a symbol which means let us work together to stop HIV/AIDS.

- (2)

My picture is about preventing HIV/AIDS.

- (3)

I want people to learn HIV/AIDS that kills.

I want people to learn that HIV/AIDS makes a person small.

I want people to learn that stop sharing sharp object.

I want people to learn that stop playing sex with a person who has HIV/AIDS.

I want people to learn to take medicine daily.

The placement of the large AIDS ribbon behind Sarah as she rejects Tom’s advances suggests that she (and more generally girls and women) is responsible for stopping the spread of HIV and AIDS. However, unlike other billboards in the collection, Sarah and Tom are depicted physically as equals, more or less, which supports the clarifying remarks found on the back of the drawing that ask us to interpret the ribbon as a symbol of the collective effort required to prevent the spread of the disease. The written remarks also describe Tom’s background (“That man got HIV/AIDS as a result of playing sex with an infected person.”), which mildly attributes some of the responsibility in HIV and AIDS prevention to his (and more generally boys’ and men’s) actions. Nevertheless, contributing to the overarching narrative thread of how individuals can prevent HIV and AIDS transmission, the immediate connotation from this drawing points to girls and women as the ultimate refusers. Sarah is responsible for rejecting Tom’s gifts and all that they imply. Sarah, and not Tom, is responsible for stopping the spread of HIV and AIDS. As we show in the next section, the children’s billboards often enabled conversations about issues or relationships that they hinted at but for a variety of reasons were not able to depict.

3.3. Interviews with Children

In this section, we summarize the salient themes that emerged from our collaborative analysis of the interviews with the children. Within each theme, we present representative excerpts, which focus on the participants’ experiences of sharing and discussing their billboard drawings with their parents and caregivers. The five themes identified are enhanced communication with parents, the effects of talking about HIV and AIDS, the benefits of participating in the study, new understandings from classmates’ billboards, and children’s real-life concerns about HIV and AIDS.

3.3.1. Enhanced Communication with Parents

In general, the children thought the billboard drawings made communication about HIV and AIDS with their parents easier. As Viola (girl) explained, her parents’ attention was on her billboard rather than on her, which made the discussion more comfortable and created an opportunity to ask questions: “The billboard drawing made it easier for me because my parent’s eyes were on my drawing as I explained; she wasn’t looking at me so I felt a little comfortable. I used this as a chance to ask [my mother] some questions about HIV and AIDS.” For other students, discussions about the billboard drawings served to quell their fears about talking about HIV and AIDS with their parents. For example, Joel (boy) emphasized that the billboard drawing discussion altered the difficult interactive pattern he typically had with his parents: “This billboard drawing made it easier for me. I did not fear my parents so much the way I have always feared. My parent was even a little friendly.” Jacob (boy) had a similar experience and noted how the billboard enabled him to talk to his parents in a new way: “I showed it to my parents and it helped me to talk more about the disease. Without it I wouldn’t have said much. They have not always been close to me so we have always kept some distance from each other.”

3.3.2. Effects of Talking about HIV and AIDS

The children’s perceptions of whether it was easy or difficult to communicate their knowledge of HIV and AIDS with their parents appeared to be connected to the type of relationship they had with their parents prior to the study. For example, some children feared punishment or judgement if they talked about HIV and AIDS. Sarah’s (girl) sense of enhanced communication with her parents was coupled with lingering fear: “Talking to them is very good but sometimes if we talk to them about it [HIV and AIDS] they think we are wasted or spoilt children. They say we have bad company.” Others, such as Jesca (girl), enjoyed the interactions with parents because they already had a strong relationship: “It is good to talk to our parents about HIV and AIDS because they know more and therefore can guide us well.” Mathias (boy) told us that advice from his parents was critical: “It is good to talk to them because they can advise you that if you get HIV, it has no cure and that you should avoid early sex.”

3.3.3. Benefits of Participating in the Study

We asked the students to reflect on their experience participating in the research study and they commented both about what they learned and what they think their parents and teachers learned. Medi (boy) summarized it this way: “This study has been good for us and I think our parents will be in a better position to talk to us more openly about HIV and AIDS in future.” Jacob emphasized several benefits of sharing his billboard drawing: “I have learnt more about the disease. I have also had a chance of talking to my parents about HIV and AIDS. They listened to me this time.” Pat (boy) more specifically explained: “… I have something because HIV can kill people and I have learnt that it helps young people to delay early marriages until they are old enough.” In relation to the information gap that exists for many children in Uganda, Jose’s (girl) comment offered important insights: “I have learnt a lot from this study and we need to continue sharing information with one another with the guidance of our teachers. All the pupils need this information so that they don’t fall victims.”

Martin (boy) stressed the responsibility of teachers for closing the information gap about HIV and AIDS: “Our teachers benefitted because here at school they are our parents so they will be able to give us more information about HIV and AIDS.” This also applied to teachers as parents, as Claudia (girl) explained: “Yes, because they have learnt more about HIV during this study, from which they can also teach their children about HIV and AIDS and how to prevent catching it.” Mary (girl) thought communication with parents would remain open: “I think it will help them be closer to me and we shall talk more about HIV and AIDS. It has been good to me because they are now more open about it.” For Martine (boy), he anticipated that because his parents had participated in the research study, “they can now also go for medical checkups [to check their HIV and AIDS status] and also talk to us without fear.”

3.3.4. New Understandings from Classmates’ Billboards

Sharing the billboards as classroom texts provided new opportunities for the students to gain more nuanced understandings of HIV and AIDS treatment and prevention. They offered very specific examples of their learnings, which in Joel’s case also expressed empathy: “I didn’t know that if you start taking the medicine for HIV and AIDS you have to continue throughout your lifetime. It is not something easy for one to do.” Several girls such as Jesca (girl) shared personal cautions that focused on prevention: “I now know that not everyone who gives you a gift is a friend. Someone may have the intention of infecting you with HIV and AIDS and you die. So I have to be careful.” Similarly, Cate emphasized: “I have learnt that if you contract HIV and AIDS you may fail to complete your studies or perform poorly because you will not attend school regularly.” Jane (girl) emphasized safe sex: “I have learnt that a healthy person should not play sex with an infected person when they are not protected.” When many of the boys shared new learnings, however, their stance was more matter-of-fact, as in Arnold’s (boy) statement: “I learnt that HIV has no cure and a doctor should not touch someone’s blood without wearing gloves since HIV and AIDS spreads faster through getting in touch with a sick persons’ blood” and Martine’s observation: “A person with HIV must go for medical checkups, receive medicines and be faithful to taking those medicines.”

3.3.5. Children’s Real-Life Concerns about HIV and AIDS

Coupled with these new understandings were emerging concerns about how the disease might affect their own lives. For Phina (girl), the billboard messages concerned her because “I have relatives who died and I was told that they died of this disease. I have to behave responsibly.” Joseph was one of the few boys who expressed more personal realizations: “I have learnt that this disease affects people. I am also a human being and that means I could also get infected if I behave badly; that is, have sex with an infected person.” Teddy (girl) explained her concerns this way: “They concern me because they are warning me not to have unprotected sex with an infected person when I grow up. Many people are dying because of HIV and AIDS.”

In summary, the children believed that the billboards they created for this research study had multiple benefits, although they also revealed some issues and concerns. In terms of benefits, the children reported that the billboards facilitated sensitive conversations in their families by mediating the exchange of difficult knowledge. The extent to which families were able to delve into the topic, however, seemed to depend largely on the existing quality of the relationships between parent and child; in the case of families with strong, trusting relationships, the billboard discussions were reportedly quite rich. Somewhat surprisingly, the children repeatedly remarked that the value of this research was in educating the adults in their lives (parents, teachers) about HIV/AIDS, so that they would be in a more-informed position to care for their own health (e.g., by getting check-ups), and to educate their children about the disease. Looking at their peers’ billboards helped to concretize some of the information they had learned about HIV and AIDS prevention, and it also prompted some empathetic reflection, which underscores the affective affordances and impact of this mode of representation. Finally, the concerns that this project raised for the children seemed to stem from concerns about safety. Several children voiced concerns for their own safety with an air of responsibility to “behave responsibly” so that they do not contract the disease.

3.4. Parents’ Perspectives

From our analysis of the interviews with parents, we identified the following themes, which we discuss below: challenges and the necessity of talking about HIV and AIDS, enhanced communication with children, children’s unexpected knowledge, benefits of participating in the study, and parents’ real-life concerns about HIV and AIDS.

3.4.1. Challenges and the Necessity of Talking about HIV and AIDS

Some parents emphasized the difficulties of talking to their children about sexual issues, as in Margaret’s (mother) statement: “Mentioning sex is not easy at all. You know quite well that parents in our society do not talk much about it and the aunts to these children are the ones with the responsibility of sex education.” Janet (mother) stressed the challenges of explaining “the details of getting into bed with a man for sex”.

Others, however, expressed a sense of obligation. For these parents, it was important to be explicit. As Nakintu (mother) told us, “it is my bounden duty to do so.” For others, such as Joseph, (father) they took the lead from their children: “because my son was the first to talk to me.” Hasifah (mother) emphasized why it was important to talk to children about HIV and AIDS: “Children need to be educated more about the disease. They need to know the risk that faces them and how to they can avoid those risks.” According to Prossy (mother), the discussion is critical with or without the drawings: “It may not make it any easier or more difficult. With or without drawings, I must talk to my child about those issues of HIV and AIDS. She is my child.”

3.4.2. Enhanced Communication with Children

Similar to their children, however, parents overwhelmingly agreed that the billboard drawings made it easier for them to talk about HIV and AIDS. As Hasifah explained: “It made it easier because I had never gone into the details of HIV and AIDS but when I asked my child about the picture he drew, he was able to tell me.” Resty (mother) described the experience this way: “In his drawing the boy tries to give the girl a gift. The child has already simplified if for me. This is one of those areas that are hard for me to talk about. Such relationships are not easy to discuss with our children. But since he started the subject, I used that drawing to give him more guidance.” It is especially difficult for fathers to talk to their daughters about issues related to sexuality, yet Lawrence (father) contributed the following to our discussion: “I think the drawings made it easier because according to the drawings some of my children have some ideas that have been difficult for me. They helped me talk to them. I used their own drawings to expand on their knowledge especially the girls.” Resty elaborated on the value of the drawings: “Children may not be free to tell us certain things but use diagrams to convey the message. One of my children drew a picture of me when I was pregnant and he showed it to me. He could not tell me directly that I was pregnant so he used this drawing. This showed me that he was getting information from somewhere else. So is the case with these pictures. They represent what these children know about HIV and AIDS.”

3.4.3. Perceived Benefits of Participation in the Study

The parents commented widely on the perceived benefits of their children participating in a study about HIV and AIDS at school. For Resty, the benefit was her child’s exposure to knowledge and information represented in the other students’ billboards: “This child has benefited a lot especially the information got after viewing the billboard drawings of their classmates.” Zaituna (mother) was very specific in her comment about her child’s understanding of HIV and AIDS patients: “My child has greatly benefited in a sense that he appears to understand the pain of HIV patients and the need for him to guard against HIV and AIDS as he grows.” Margaret speculated on how the new information her child garnered would also open up conversations among peers: “This child has benefitted a lot. Many people do not fear contracting the disease which has no cure. As a child he will even pass on the information to his peers. He will always remember that HIV and AIDS kills. I had not told him much as a parent because I had no beginning point. Now I have the guts to talk to him.”

3.4.4. Children’s Unexpected Knowledge

Most parents came to the realization that their children knew much more about HIV and AIDS than they thought, especially about the risks involved. Joseph shared the following about his son’s knowledge: “…he has learned the means through which HIV and AIDS is contracted and that it is prevalent in circumstances in which we engage in unprotected sex.” In terms of prevention, Resty offered, “I learnt that my child knows that such gifts may lead to demand of for sex in return with an intention to infect the other.” The billboards also portrayed knowledge that the parents did not expect. As Teopista (mother) explained, “I am surprised that he can draw such a picture. I thought that he had copied it from the blackboard and asked him if they had all drawn the same picture. I realized they were different. This was his own creation.” Similarly, Joseph told us: “The emaciated man surprised me a lot because I did not think that is the way he perceives people with HIV and AIDS.” Sarah’s (mother) comment focused more on the realization that parents are not their children’s only source of information about HIV and AIDS: “His drawing surprised me because this is something we had never talked about. These children are getting information from other sources.” Some parents such as Suzan (mother) also shared that they had gained personal insights from their children’s drawings: “I had never talked much to these children about how to care for someone that is HIV positive. I have always told these children to stay away from them but when I looked at one of their picture, I realized I have all along been wrong. We need to care for people that are HIV positive.”

3.4.5. Real-Life Concerns about HIV and AIDS

Not only did the content of the children’s billboards surprise parents, it also raised real-life concerns about the disease, particularly the possibility of their children contracting the disease. As Hasifah noted: “It concerns me because with all the knowledge the children have, you cannot know what will happen to your kid in future.” Resty’s concern emanated from a common billboard narrative, that of sugar daddies propositioning girls with gifts: “As a parent, I am concerned because if they [sugar daddies] begin giving my child gifts she may be seduced into sex and thereafter HIV and AIDS.” Phiona (mother) expressed a similar worry: “The drawing reminded me of my sister’s daughter who dropped out of school as a result of such gifts. I often give her as an example to my daughter.” Growing concerns about real-life issues, however, also became the impetus for engaging in meaningful conversations. As Sarah explained, “The drawings concern me because the society we are living in today has people behaving that way. This is the time to talk intensely to my child about HIV and AIDS.” Joseph’s comment about his child’s portrayal of people HIV and AIDS emphasizes the physical effects of the disease: “When you look at the picture it is the way people are affected when they get HIV and AIDS. One becomes small.”

To summarize, although parents shared their discomfort about discussing HIV and AIDS-related matters with their children, they were also aware of the necessity and generally agreed that the billboard drawings made it easier to engage in a conversation. They highlighted the benefits of participating in the research study and most were surprised at their children’s level of knowledge about the topic, which raised new concerns about risk in the community. These concerns may also have arisen because viewing the billboards, designed from a child’s perspective, made visible knowledge and experiences that were previously unknown to parents.

4. Discussion

Returning to the concept of makerspace, it was evident in our study that this exploratory space enabled children to document, explore, and share their understandings and experiences of HIV and AIDS. Our conceptualization of makerspaces included the making cycle (i.e., the site of production, text, circulation, and audiences), with a focus on visual and linguistic modes as tools for thinking, creating, and communicating. Our discussion focuses on key findings across sites of meaning making and in relation to the billboards as a multimodal literacy.

For our makers, the site of production provided an opportunity to experiment with visual and linguistic communicative resources, integral to developing multimodal literacies (see, for example, Kress and Jewitt, 2003 [

27]; Kendrick, 2016 [

17]). They were able to design powerful narratives through visual composition, using resources such as spatial arrangements (e.g., perspective), symbols (e.g., the red AIDS ribbon), color, and content to communicate their messages. When we examine the artifacts created, particularly noteworthy were the makers’ representations of sexual relationships; they most typically positioned men and boys as instigators of sexual acts and women as more passive recipients. This traditional pattern of heterosexual relationships is especially pronounced in the region where the study was conducted. Moreover, because the children represented male actors as those spreading the disease, we assume they were aware it was primarily men in this community who were infected and that it would be taboo for women to initiate any type of sexual relationship.

The interdisciplinary and cultural knowledge embedded in the billboard artifacts also include men’s institutionalized authority over women and their control of economic resources, an issue that has been identified as a key facilitator of multiple partnerships for men (Namazzi, 2015) [

28]. These unequal power and gender norms, which expose adolescent girls and young women to higher risks of HIV and AIDS, early marriages, pregnancies, and coerced sex (Ninsiima et al., 2018) [

29], was a strong theme integrated into the billboard narratives and was referenced in our interviews with the child participants and parents. The children’s understanding of these risks is nuanced, with indications that women/girls have the power to make the right choice by saying no to gifts and sugar daddies, evident in the confident stance of the female actors in both examples of the billboards, but that they also have fear that saying no may not be enough to ensure their safety.

In their detailed review of the various dimensions and possibilities of makerspaces, Sheridan et al. (2014) [

8] conclude that much of the learning is in the making process. For our makers, the site of viewing was equally important in the learning process. Marsh et al. (2018:6) [

13] have emphasized the importance of makers’ reflecting “critically on modes of dissemination, to ensure most effective use of them”. Across the interviews, both adults and children emphasized that the exhibition as a means of dissemination provided opportunities to gain new understandings about HIV and AIDS. Critically, unlike the national campaign billboards, the children’s billboards uniquely showcased understandings and issues from the perspective of young children rather than adults, making visible their emotions and fears, scientific and health knowledge, and cultural understandings about HIV and AIDS. Many of the child participants also expressed an empathetic reflection on their peers’ billboards, which foregrounds the affective dimension of the billboard productions. It was also surprising how the students placed worth on their participation in the study, emphasizing their desire to educate adults in their lives to take better care of themselves as part of preventing HIV and AIDS. As curricular materials, the billboards offered new insights into experiences and identified barriers to prevention that were previously unknown to parents and children. It was also evident to us that the inclusion of an exhibition in our research design placed important value on the audience. We were particularly struck by the prominence of the makers’ names on their billboards, which signaled a strong sense of ownership and pride in what they had created.

The impetus for this study stemmed from an article in Uganda’s national newspaper

New Vision (quoted at the outset of this article) that drew attention to the “information gap” between children and adults in HIV and AIDS education. In that same

New Vision article, Sarah Nakku, Community Mobilization and Networking Advisor to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS), stressed that reaching a zero-infection rate of the disease hinged on educating children. She advised: “By the age of eight or nine, children are having their first sexual intercourse and this is the reality. Teachers, parents and guardians, it is your role to focus on giving children information regarding HIV/AIDS and encourage them to abstain till they are old enough. Otherwise you will teach and invest in children that are sick and will die young” (Vision Reporter, 2015) [

1].The results from our study demonstrate how makerspaces that enable learners to use multimodal communicative resources can provide teachers, parents, and other caregivers critical curricular and family learning materials for HIV and AIDS education that are meaningfully embedded in children’s own lives, experiences, perspectives, and identities, all of which have been largely ignored in many Ugandan primary schools (see also Becker-Zayas et al., 2018) [

2]. Although the parents previously feared that their children were too young to be told anything about HIV and AIDS, through the billboard exhibition and discussion they discovered that although their children had more knowledge about HIV and AIDS than they expected, and that they had an obligation to “fill in the gaps” and engage in deeper conversations about the prevention and treatment of the disease. Even though these more open conversations may depend to some degree on family relationships more broadly, we see great potential for makerspaces to serve as a starting point for parent engagement.