“Helping Nemo!”—Using Augmented Reality and Alternate Reality Games in the Context of Universal Design for Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Inclusive Education

2.2. Multimodal Learning and Students’ Engagement and Participation in Learning through the Prism of Universal Design for Learning

2.3. Contemporary Multimodal Learning: Augmented Reality and Serious Alternate Reality Games

“ARGs invite players to imagine and inhabit a past, present, or future alternate world, requiring that they look critically at the information they find, constantly asking “what if” questions. By embedding gameplay and story seamlessly into existing, everyday technologies, ARGs neither acknowledge nor promote the fact that they are games. The lines between “what’s real” and “what’s not” are unclear, fostering “what-if” interrogation.”

- (1)

- What is the impact of an alternate reality game enhanced with AR on students’ engagement in learning?

- (2)

- In what ways do the students perceive their participation in the learning process in the context of an alternate reality game enhanced with AR?

- (3)

- In what ways do the affordances provided by the combination of ARG–AR in the context of UDL respond to students’ variability?

3. Methodology

3.1. Context and Participants

3.1.1. Research Design

3.1.2. Participants

3.2. Ethical Issues

3.3. Preparation and Design Considerations

Greek language Cognitive Objectives:The students must:

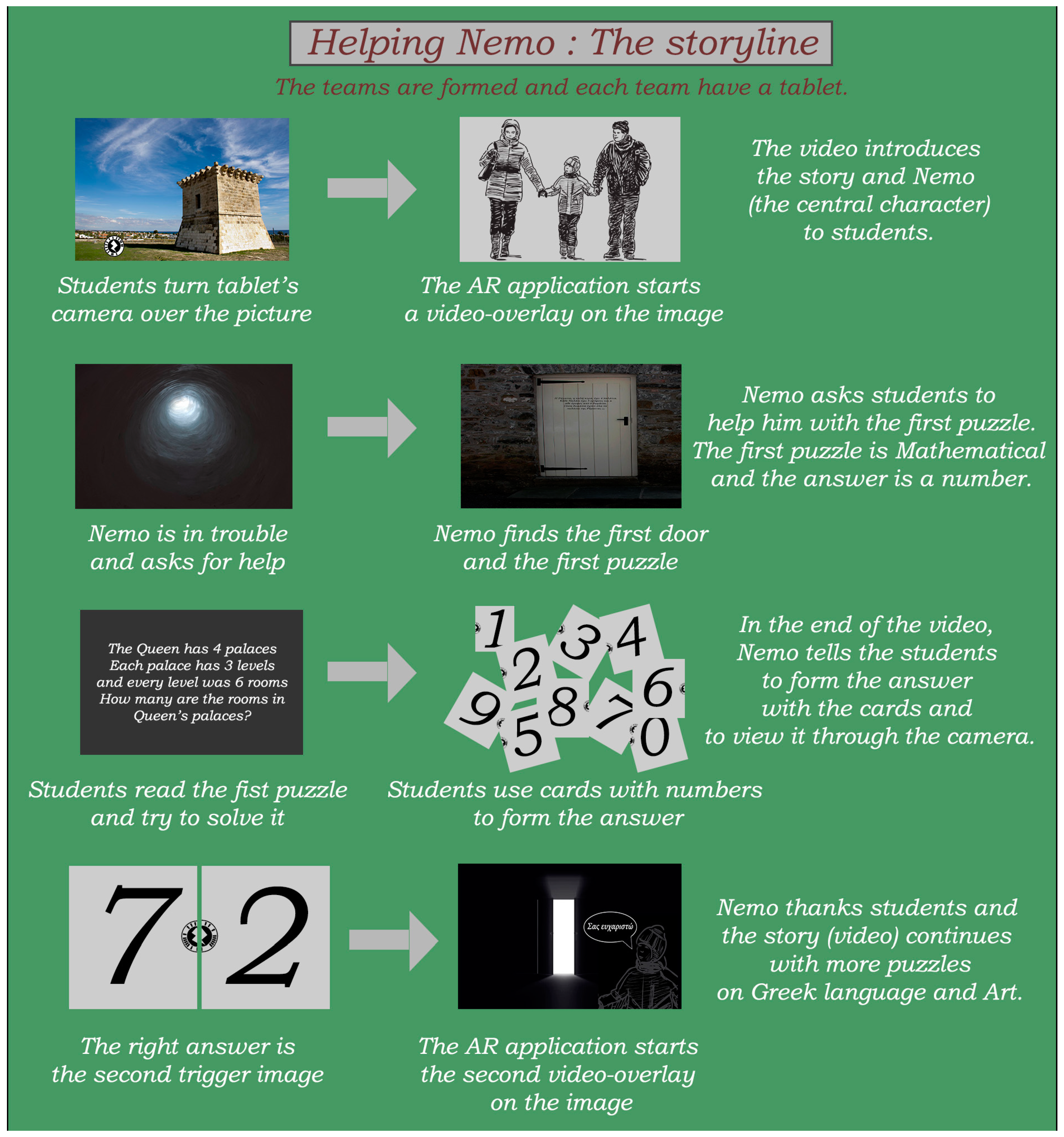

3.3.1. Helping Nemo: Designing the ARG–AR

3.3.2. Teaching Intervention

3.4. Data Collection

3.4.1. Activity 1: Students’ Short Reflection Statements

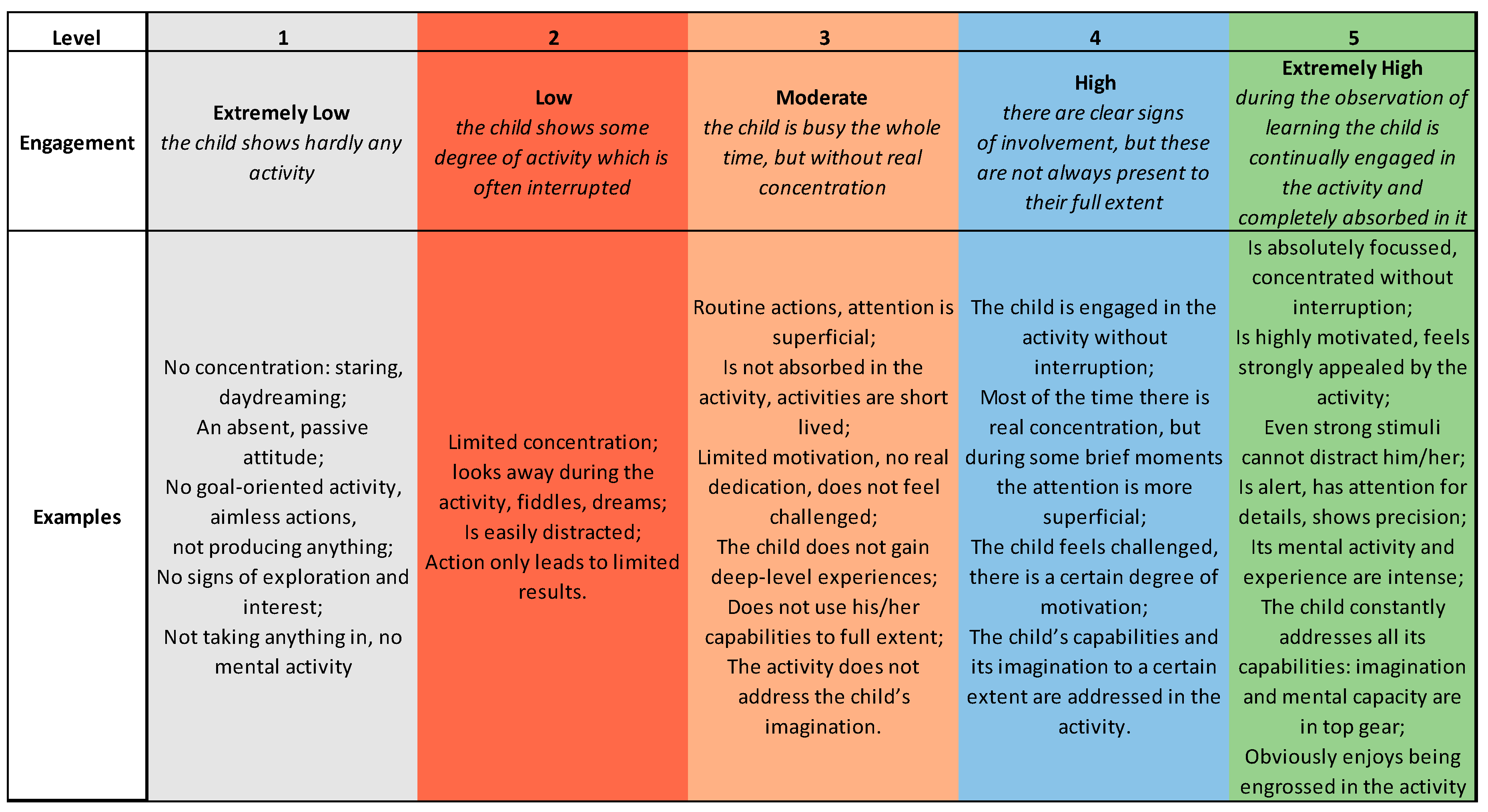

3.4.2. Activities 1 and 2: Leuven Scale

3.4.3. Activity 1 and 2: Focus Groups and Teacher’s Reflective Diary

3.5. Analysis

4. Results

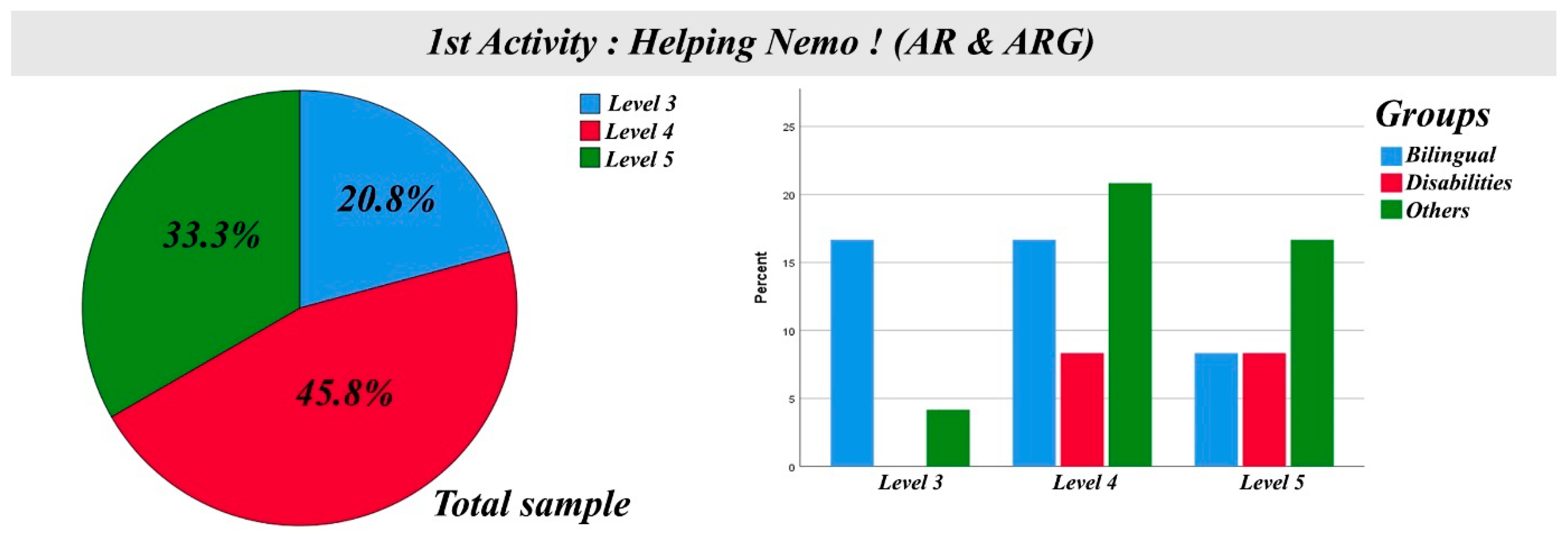

4.1. Results of Activity One: Helping Nemo!

4.1.1. Quantitative Results

4.1.2. Qualitative Results

R: What did you like more from what we did today? From what you did last time with your teacher? What was more wow?S12: I had a great time with my team, we solved puzzles, and we learned more things about the myth of the Queen.S3: I liked that we worked together and solved the puzzles and learned about the Queen’s legend.S1: I liked that we solved the puzzles as a group. I liked my team.S15: I liked it because we solved puzzles and learned more.S19: I liked the way we collaborated and we have to say thank you to our teacher for this gift.

«Almost all children participated in the lesson more than usual. They interacted widely with each other throughout the activity. The children seemed to find a way to work together to solve the puzzles. Without any intervention or prompting from me, they would take the tablet in turns and work together when they needed to find the correct answer to a puzzle.»

R: What did you like during this activity?S5: I liked that we had to place the tablet over the image and watch a video.S8: I liked that we used the tablet to open the doors.

«I had a concern about using technology to such an extent in the classroom. I did not know how the students would respond, if they were going to encounter any difficulties. In the end, the only thing they asked from me was the tablet’s password, and the rest of the activity took place faster and easier than I had expected».

«By using the tablets and feeling that they were part of the game they felt that they had learned ‘on their own’ after solving the puzzles and had almost come to the end of the story with no help from their teacher but working in groups together.»(teacher’s diary)

R: Would you recommend it to some of your other classmates who haven’t done it before?S8: Yes.R: Why?S8: Because they may not know what to do and I would be able to tell them what to do.

«The kids perceived what we did as something very creative and important. In the breaks that followed I heard them discuss and brag about it to their friends from other classes»(teacher’s diary)

R: What do you think that you learned with all the things that we did today and last time?S11: Things about our mum and our dad, for them to be excited.R: What kind of things?S11: The puzzles and that sort of things.

R: Would you like to do similar activities in other subjects?S19: Yes.R: Why?S19: Because it was amazing.S5: Because I had fun.S7: Because it was fun!S20: Today we learned that the lesson…looks…like… a game!

«all the children had fun and treated the activity as a game»(teacher’s diary)

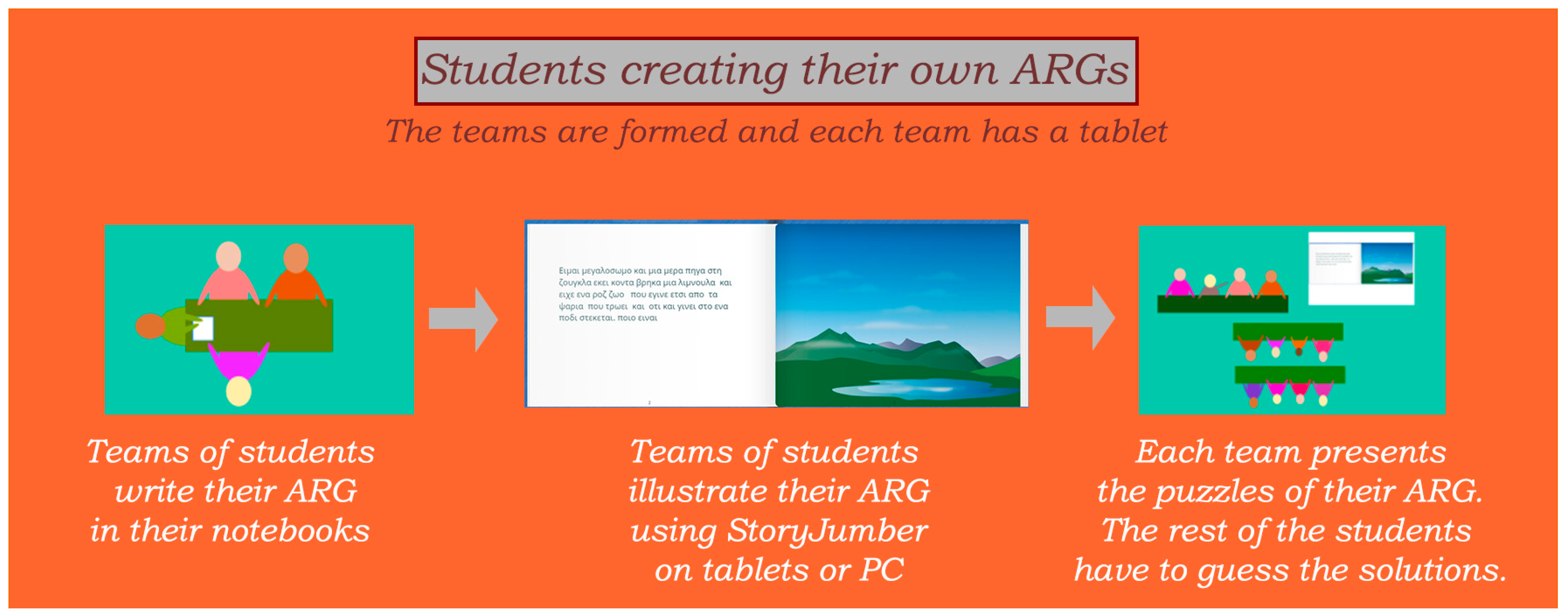

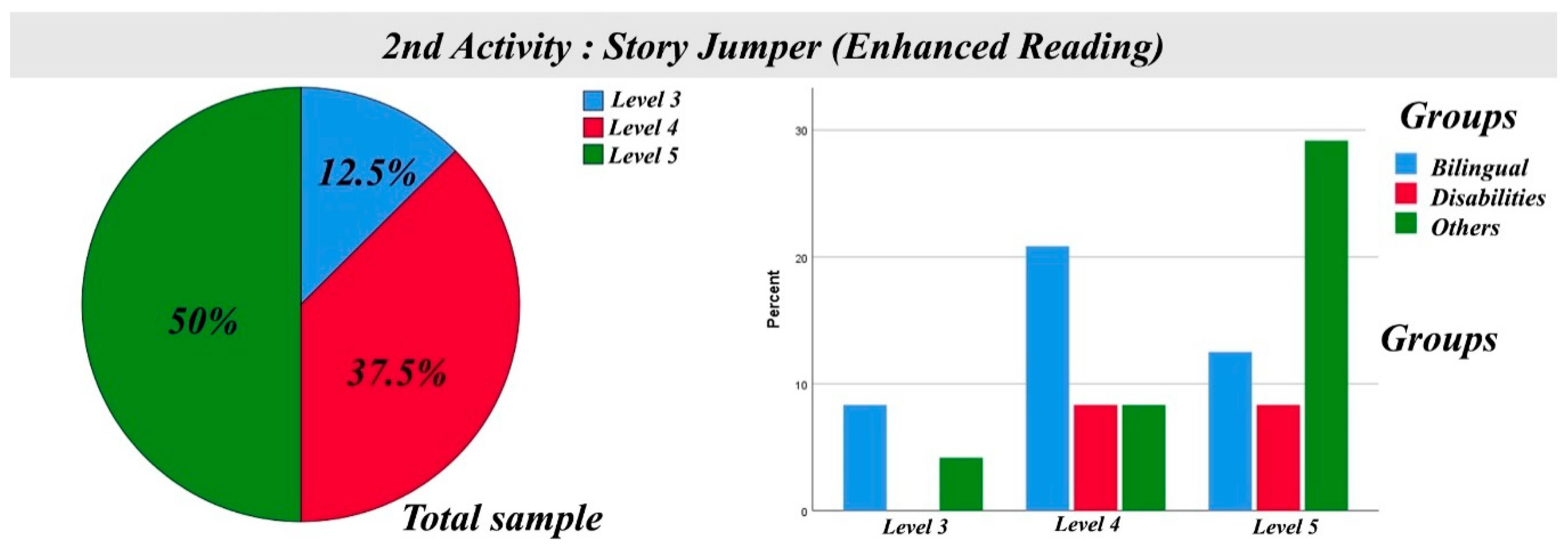

4.2. Results of Activity 2: Students Creating Their Own ARGs

4.2.1. Quantitative Results

4.2.2. Qualitative Results

R: Do you have any ideas so that these activities can become better?S20: I would like to continue our puzzle-story, finish all the pages and have it as a memento.R: What did you like most from all we did today?S22: I liked that we all did the puzzle-story because we would have it and remember that we were in second grade with our teacher.

R: What did you like most about everything we did?S3: That we inserted the photos.S9: I liked that we were inserting the pictures.S25: I liked that we created a puzzle-story, and we uploaded the pictures and we wrote the puzzle-story by ourselves.S17: I liked the computer.R: Why did you like that?S17: Because we could insert the pictures and do things by ourselves and it was very nice.

4.3. Results Referring to Activity 1 & Activity 2

R: Would you like to do similar activities in other subjects?S2: Yes.R: Why?S3: I would like to do it in other subjects because I liked puzzle-solving a lot.S16: I would like to do it again because I had fun with my team and the puzzles.S12: I would like to do this next year too, writing a puzzle-story also do the activity with the Queen’s tower.

R: I want you to think a little bit and tell me some ideas about how we can do these activities better.S2: We might have used more tablets and have more puzzles it would be nicer.R: Why?S2: Because we had only three puzzles and they were very few if we had more puzzles we were going to have more fun. It will have more action if we have more!S4: We could change the topic with the tablets a little bit and learn more things.R: Do you mean instead of the Queen’s tower that you did last time to do something else?S4: Yes, to learn more things.S8: I would like to do all 40 class periods in this way!

«The kids got excited about the puzzles, and they kept asking me to do something similar in other lessons with even more puzzles. They liked using the tablets and they told me that they would love it even more if they had more. Most kids would like to take some time to use the tablet and continue the activity».(teacher’s diary)

«I was very impressed with the case of a student with selective mutism who was talking with his/her classmates and participating in the lesson like never before. In addition, the bilingual children participated in the activity more than they usually do. If I compare each student with his/her own level of engagement in conventional lessons, the level of engagement during these activities was higher for each individual».«The students understood what was requested from them from the first minutes and worked as a team to solve the puzzles. All children were working on equal terms, and someone who doesn’t know them would not be able to identify academically strong and weak students».

5. Discussion

5.1. What is the Impact of an Alternate Reality Game Enhanced with AR on Students’ Engagement in Learning?

5.2. In What Ways do the Students Perceive Their Participation in the Learning Process in the Context of an Alternate Reality Game Enhanced with AR?

“Emotions have diagnostic value for the teacher because they reveal underlying cognitions, commitments and concerns. Teachers need to be aware of their students’ motivational beliefs and be sensitive to their emotions as this information can inform the design of the learning process. Their own behaviour and their teaching and evaluation practices trigger specific emotions and motivational beliefs in the students, which in turn affect the quality of the learning which takes place.”

5.3. In What Ways do the Affordances Provided by the Combination of ARG–AR, in the Context of UDL, Respond to Students’ Variability?

6. Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Squire, K.; Giovanetto, L.; Devane, B.; Durga, S. Building a Self-Organizing Game-Based Learning. TechTrends 2005, 49, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl, K.; Rowsell, J. Travel Notes from the New Literacy Studies: Instances of Practice; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 2006; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Street, B.V. New Literacies, New Times: Developments in Literacy Studies BT—Literacies and Language Education; Street, B.V., May, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, M. Literacies across Media: Playing the Text; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Heron-Hruby, A.; Wood, K.D.; Mraz, M.E. Introduction: Possibilities for Using a Multiliteracies Approach with Struggling Readers. Read. Writ. Q. 2008, 24, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.; Clinton, K.; Purushotma, R.; Robison, A.J.; Weigel, M. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century; From The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Reports on Digital Media and Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Coiro, J.; Killi, C.; Castek, J. Designing Pedagogies for Literacy and Learning through Personal Digital Inquiry. Remixing multiliteracies: Theory and Practice from New London to New Times; Language and Literacy Series; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, B.; Kalantzis, M. The Things You Do to Know: An Introduction to the Pedagogy of Multiliteracies. In A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- The New London Group. A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1996, 66, 60–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, M. Reassembling Difference? Rethinking Inclusion through/as Embodied Ethics. Hum. Relations 2019, 72, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembylas, M. A Butlerian Perspective on Inclusion: The Importance of Embodied Ethics, Recognition and Relationality in Inclusive Education. Camb. J. Educ. 2019, 49, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Booth, T.; Dyson, A. Understanding and Developing Inclusive Practices in Schools: A Collaborative Action Research Network. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2004, 8, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, L.; Black-Hawkins, K. Exploring Inclusive Pedagogy. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2011, 37, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçayır, M.; Akçayır, G. Advantages and Challenges Associated with Augmented Reality for Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Educ. Res. Rev. 2017, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Liu, X.; Cheng, W.; Huang, R. A Review of Using Augmented Reality in Education from 2011 to 2016. In Innovations in Smart Learning; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, S.C.-Y.; Yaoyuneyong, G.; Johnson, E. Augmented Reality: An Overview and Five Directions for AR in Education. J. Educ. Technol. Dev. Exch. 2011, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, C.L.; Green, M. Preservice Teachers’ Perceptions of Augmented Reality. In Literacy Summit Yearbook; Texas Association for Literacy Education: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2016; pp. 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, K.-H.; Tsai, C.-C. Children and Parents’ Reading of an Augmented Reality Picture Book: Analyses of Behavioral Patterns and Cognitive Attainment. Comput. Educ. 2014, 72, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, W. ICTs and Disability: Exploring the Human Dimensions of Technological Engagement. Technol. Disabil. 2005, 17, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronack, S.C. The Role of Immersive Media in Online Education. J. Contin. High. Educ. 2011, 59, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsignore, E.; Hansen, D.; Kraus, K.; Visconti, A.; Fraistat, A. Roles People Play: Key Roles Designed to Promote Participation and Learning in Alternate Reality Games. In Proceedings of the 2016 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, Austin, TX, USA, 16–19 October 2016; pp. 78–90. [Google Scholar]

- Economides, K. For ARGument’s Sake! The Pros and Cons of Alternate Reality Gaming in Higher Education. In IFIP World Conference on Computers in Education, Dublin, Ireland, 3–6 July 2017; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam, M.; Jagoda, P.; Fabiyi, C.; Lyman, P.; Wilson, C.; Hill, B.; Bouris, A. Alternate Reality Games as an Informal Learning Tool for Generating STEM Engagement among Underrepresented Youth: A Qualitative Evaluation of the Source. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2017, 26, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, T.; Stansfield, M.; Hainey, T.; Josephson, J.; O’Donovan, A.; Ortiz, C.R.; Tsvetkova, N.; Tsvetanova, S. Arguing for Multilingual Motivation In Web 2.0: Using Alternate Reality Games to Support Language Learning. In Proceedings of the 2nd European Conference on Games Based Learning: ECGBL, Barcelona, Spain, 16–17 October 2008; Academic Conferences Limited: Sonning Common, UK, 2008; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsignore, E.; Kraus, K.; Ahn, J.; Visconti, A.; Fraistat, A.; Druin, A.; Hansen, D. Alternate Reality Games: Platforms for Collaborative Learning. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of the Learning Sciences, Sydney, Australia, 2–6 July 2012; Volume 1, pp. 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, T.M.; Stansfield, M.; Hainey, T. An Alternate Reality Game for Language Learning: ARGuing for Multilingual Motivation. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 1389–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.; Rose, D.H.; Gordon, D.T. Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice; CAST Professional Publishing: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, L. Inclusive Education: Romantic, Subversive or Realistic? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 1997, 1, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liasidou, A. Inclusive Education, Politics and Policymaking; Continuum: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gillett-Swan, J.; Sargeant, J. Assuring Children’s Human Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression in Education. Int. J. Speech. Lang. Pathol. 2018, 20, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, A.; Ainscow, M.; Bouya-Aka, A.; Cruz, M.; Eklindh, K.; Ferreira, W. Guidelines for Inclusion: Ensuring Access to Education for All; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, T. Stories of Exclusion: Natural and Unnatural Selection. In Exclusion from School: Multi-Professional Approaches to Policy and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 1996; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture (European Commission); PPMI. Preparing Teachers for Diversity: The Role of Initial Teacher Education; European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jewitt, C.; Bezemer, J.; O’Halloran, K. Introducing Multimodality; Routledge: New York, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G. Transposing Meaning: Translation in a Multimodal Semiotic Landscape. In Translation and Multimodality; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 24–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, B.; Kalantzis, M. Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bezemer, J.; Kress, G. Writing in Multimodal Texts: A Social Semiotic Account of Designs for Learning. Writ. Commun. 2008, 25, 166–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezemer, J.; Jewitt, C. Multimodal Analysis: Key Issues. In Research Methods in Linguistics; Continuum: London, UK, 2010; pp. 180–197. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, B.; Kalantzis, M. Making Sense: Reference, Agency, and Structure in a Grammar of Multimodal Meaning; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, B.; Kalantzis, M. “Multiliteracies”: New Literacies, New Learning. Pedagog. Int. J. 2009, 4, 164–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, M.J.; Sorin, R.; Nolan, J.; Chu, S. Multimodal Meaning-Making for Young Children: Partnerships through Blogging. In Understanding Digital Technologies and Young Children; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2015; pp. 92–111. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, C. Technology Uses and Language–A Personal View. In Inclusive Language Education and Digital Technology; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2013; pp. 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, S. Toward an Accessible Pedagogy: Dis/Ability, Multimodality, and Universal Design in the Technical Communication Classroom. Tech. Commun. Q. 2010, 19, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, B.; Murrell, S. Evaluating Multimodal Literacies in Student Blogs. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2014, 45, 926–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankey, M.; Birch, D.; Gardiner, M. Engaging Students through Multimodal Learning Environments: The Journey Continues. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference of the Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education: Curriculum, Technology and Transformation for an Unknown Future, ASCILITE 2010, Sydney, Australia, 5–8 December 2010; pp. 852–863. [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht, P.; Green, L. Responding to the Challenges of Inclusive Education; Van Schaik: Cape Town, South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, J. The Three Block Model of Universal Design for Learning (UDL): Engaging Students in Inclusive Education. Can. J. Educ. 2013, 36, 153–194. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.0; CAST: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, M.G.; Trezek, B.J. Universal Design and Multiple Literacies: Creating Access and Ownership for Students with Disabilities. Theory Pract. 2006, 45, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blamires, M. Universal Design for Learning: Re-establishing Differentiation as Part of the Inclusion Agenda? Support Learn. 1999, 14, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.-H. Exploring Parents’ Conceptions of Augmented Reality Learning and Approaches to Learning by Augmented Reality with Their Children. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2017, 55, 820–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunleavy, M.; Dede, C.; Mitchell, R. Affordances and Limitations of Immersive Participatory Augmented Reality Simulations for Teaching and Learning. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2009, 18, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurzick, D.; White, K.F.; Lutters, W.G.; Landry, B.M.; Dombrowski, C.; Kim, J.Y. Designing the Future of Collaborative Workplace Systems: Lessons Learned from a Comparison with Alternate Reality Games. In Proceedings of the 2011 iConference, Seattle, WA, USA, 8–11 February 2011; pp. 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Chess, S.; Booth, P. Lessons down a Rabbit Hole: Alternate Reality Gaming in the Classroom. New Media Soc. 2014, 16, 1002–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, R.; Mallon, B.; Connolly, C. Assessment in Serious Alternate Reality Games. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Virtual Worlds and Games for Serious Applications (VS-Games), Wurzburg, Germany, 5–7 September 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research. Handb. Qual. Res. 1994, 2, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegerif, R.; Mercer, N. Using Computer-Based Text Analysis to Integrate Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Research on Collaborative Learning. Lang. Educ. 1997, 11, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockett, S.; Perry, B. Researching with Young Children: Seeking Assent. Child Indic. Res. 2011, 4, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, L.R. Educational Research Competencies for Analysis and Application; Mackmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. Children as Respondents. In Research with Children: Perspectives and Practices; Christensen, P., James, A., Eds.; Falmer Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.; Hart, L. The Impact of Context on Data. In Developing Focus Group Research: Politics, Theory and Practice; Barbour, R., Kitzinger, J., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 843–860. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. Research Designs; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe, G.; Göth, C. Mobile Learning with a Mobile Game: Design and Motivational Effects. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2005, 21, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, C.; Lee, M.J.W. Personalised and Self Regulated Learning in the Web 2.0 Era: International Exemplars of Innovative Pedagogy Using Social Software. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2010, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekaerts, M. The Crucial Role of Motivation and Emotion in Classroom Learning. In The Nature of Learning: Using Research to Inspire Practice; Dumont, H., Istance, D., Benavides, F., Eds.; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Boekaerts, M. Emotions, Emotion Regulation, and Self-Regulation of Learning. Handb. Self-Regul. Learn. Perform. 2011, 5, 408–425. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.T. Students’ Perspective on Intrinsic Motivation to Learn: A Model to Guide Educators. Int. Christ. Community Teach. Educ. J. 2010, 6, 5. [Google Scholar]

- University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. All Work and No Play Makes for Troubling Trend in Early Education. Available online: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/02/090212125137.htm (accessed on 29 February 2020).

- Lillemyr, O.F.; Søbstad, F.; Marder, K.; Flowerday, T. A Multicultural Perspective on Play and Learning in Primary School. Int. J. Early Child. 2011, 43, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.; Salter, A. Playing Art Historian: Teaching 20th Century Art through Alternate Reality Gaming. Int. J. Scholarsh. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2016, 1, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Jagoda, P.; Gilliam, M.; McDonald, P.; Russell, C. Worlding through Play: Alternate Reality Games, Large-Scale Learning, and “The Source”. Am. J. Play 2015, 8, 74–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bressler, D.M.; Bodzin, A.M. A Mixed Methods Assessment of Students’ Flow Experiences during a Mobile Augmented Reality Science Game. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2013, 29, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dede, C. Immersive Interfaces for Engagement and Learning. Science 2009, 323, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, Y.; Kyza, E.A. Relations between Student Motivation, Immersion and Learning Outcomes in Location-Based Augmented Reality Settings. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 89, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopfer, E. Augmented Learning: Research and Design of Mobile Educational Games; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shute, V.J.; Becker, B.J. Innovative Assessment for the 21st Century; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moseley, A.; Whitton, N.; Culver, J.; Piatt, K. Motivation in Alternate Reality Gaming Environments and Implications for Learning. In Proceedings of the 3rd European Conference on Games Based learning, Graz, Austria, 12–13 October 2009; pp. 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- Kolikant, Y.B.-D. Using ICT for School Purposes: Is There a Student-School Disconnect? Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Z.; McMahon, D.D.; Rosenblatt, K.; Arner, T. Beyond Pokémon: Augmented Reality Is a Universal Design for Learning Tool. SAGE Open 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesolin, A.; Tsinakos, A. Opening Real Doors: Strategies for Using Mobile Augmented Reality to Create Inclusive Distance Education for Learners with Different-Abilities. In Mobile and Ubiquitous Learning; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.T.; Fogler, H.S. The Investigation and Application of Virtual Reality as an Educational Tool. In Proceedings of the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference, Anaheim, CA, USA, 25–28 June 1995; pp. 1718–1728. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stylianidou, N.; Sofianidis, A.; Manoli, E.; Meletiou-Mavrotheris, M. “Helping Nemo!”—Using Augmented Reality and Alternate Reality Games in the Context of Universal Design for Learning. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10040095

Stylianidou N, Sofianidis A, Manoli E, Meletiou-Mavrotheris M. “Helping Nemo!”—Using Augmented Reality and Alternate Reality Games in the Context of Universal Design for Learning. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(4):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10040095

Chicago/Turabian StyleStylianidou, Nayia, Angelos Sofianidis, Elpiniki Manoli, and Maria Meletiou-Mavrotheris. 2020. "“Helping Nemo!”—Using Augmented Reality and Alternate Reality Games in the Context of Universal Design for Learning" Education Sciences 10, no. 4: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10040095

APA StyleStylianidou, N., Sofianidis, A., Manoli, E., & Meletiou-Mavrotheris, M. (2020). “Helping Nemo!”—Using Augmented Reality and Alternate Reality Games in the Context of Universal Design for Learning. Education Sciences, 10(4), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10040095